1. Introduction

The rapid growth of the global mining and infrastructure sectors has led to an increasing demand for reliable ground improvement techniques that can enhance the engineering performance of weak and problematic soils. In many parts of India and other tropical regions, expansive black cotton soils and kaolinitic clays are widely encountered. These soils are characterised by high plasticity, significant volumetric changes, and low bearing capacity, posing major challenges for mine haul roads, foundations, embankments, and tailings storage facilities. Traditional solutions often involve cement and lime stabilisation, which, although technically effective, are increasingly being scrutinised due to their high embodied energy and carbon footprint.

Globally, the cement industry is responsible for approximately 8% of anthropogenic CO

2 emissions, making it one of the most significant industrial contributors to greenhouse gas emissions. Cement production requires high-temperature calcination, consuming approximately 3.5–4.5 GJ/t of energy, while also emitting process-related CO

2 during the decomposition of limestone [

1,

2]. This carbon-intensive process is incompatible with the decarbonisation pathways necessary to meet national and international net-zero targets, particularly in the infrastructure and mining sectors, where large volumes of subgrade stabilisation are required. In addition to emissions, cement-based stabilisation often requires high moisture contents, intensive compaction energy, and significant logistics—all of which compound the energy burden during field execution.

In response to these environmental and energy challenges, attention has shifted toward low-carbon and energy-efficient alternative stabilisers, particularly industrial by-products and recycled materials. Among these, waste glass powder (GP) has gained prominence due to its high amorphous silica content, pozzolanic reactivity, and low energy consumption during processing. Quantitatively, GP production requires only 0.5–0.7 GJ/t for crushing and grinding, compared with 3.5–4.5 GJ/t required for cement clinker production [

1,

2]. This represents an ≈85% lower embodied energy, confirming that GP is a genuinely low-energy stabiliser. The material can be produced through relatively low-energy crushing and grinding of post-consumer soda–lime glass, thereby bypassing the need for energy-intensive manufacturing steps typically associated with cement or lime. This makes GP a circular economy material, capable of both diverting waste from landfills and reducing the embodied carbon of construction projects.

Previous research has explored the engineering potential of GP in improving soil behaviour. Studies by Jani and Hogland (2014), Arulrajah et al. (2017), Eyo et al. (2021), and Blayi et al. (2023) [

3,

4,

5,

6] reported that GP can enhance unconfined compressive strength (UCS) and California Bearing Ratio (CBR), and reduce plasticity and swelling potential when used at moderate replacement levels. These improvements are attributed to its pozzolanic reaction with soil minerals, resulting in a denser and stronger stabilised matrix. Furthermore, GP can be sourced locally and processed with significantly lower energy inputs compared to cement, which makes it particularly attractive for remote mining operations with constrained energy supply chains.

A comparative assessment of published studies on waste glass powder stabilisation shows broadly consistent trends but method-dependent variability. Most investigations report optimum GP dosages in the 10–15% range, with typical UCS gains of 25–90% and CBR improvements of 1.5–3 times over untreated soils. Studies that utilise glass powder ground to ≤75 µm consistently report higher pozzolanic activity and greater strength enhancement [

3,

7,

8]. Differences across studies primarily arise from soil mineralogy (montmorillonitic vs. kaolinitic), curing conditions (ambient vs. elevated temperature), and GP fineness distribution. These similarities and discrepancies highlight the need for standardised evaluation frameworks. The present study contributes to the understanding of mechanical response, energy demand, and carbon performance by quantifying these parameters under controlled fineness and ambient curing conditions, thereby addressing limitations observed in prior work.

Despite these promising results, a critical gap remains in the literature. Most existing studies on soil stabilisation with alternative binders have focused either on mechanical performance or environmental benefits in isolation. There is a lack of integrated frameworks that combine energy investment, mechanical response, and carbon accounting for evaluating the true sustainability of such systems. In mining and infrastructure applications—where stabilisation often involves thousands of tonnes of soil—this gap is particularly significant. Decision-making at this scale requires not only strong data but also a quantitative understanding of energy consumption and carbon implications to support sustainable design and procurement policies.

To address this gap, the present study investigates the energy–performance–carbon nexus of GP-stabilised black cotton and kaolinitic soils. An extensive laboratory programme was conducted to evaluate the influence of varying GP contents (0–20%) on index properties, compaction characteristics, strength behaviour, and swelling potential. These experimental results were then coupled with embodied energy and CO2 emission calculations to assess the relative efficiency of GP compared to conventional cement stabilisation. An Energy Performance Index (EPI) was introduced to express the strength gained per unit of energy invested, enabling direct benchmarking between different stabiliser strategies. The overall goal is to develop a holistic evaluation framework that supports the adoption of low-energy, low-carbon stabilisers in large-scale mining infrastructure, in alignment with circular economy principles and UN SDGs 9, 12, and 13.

2. Materials and Methods

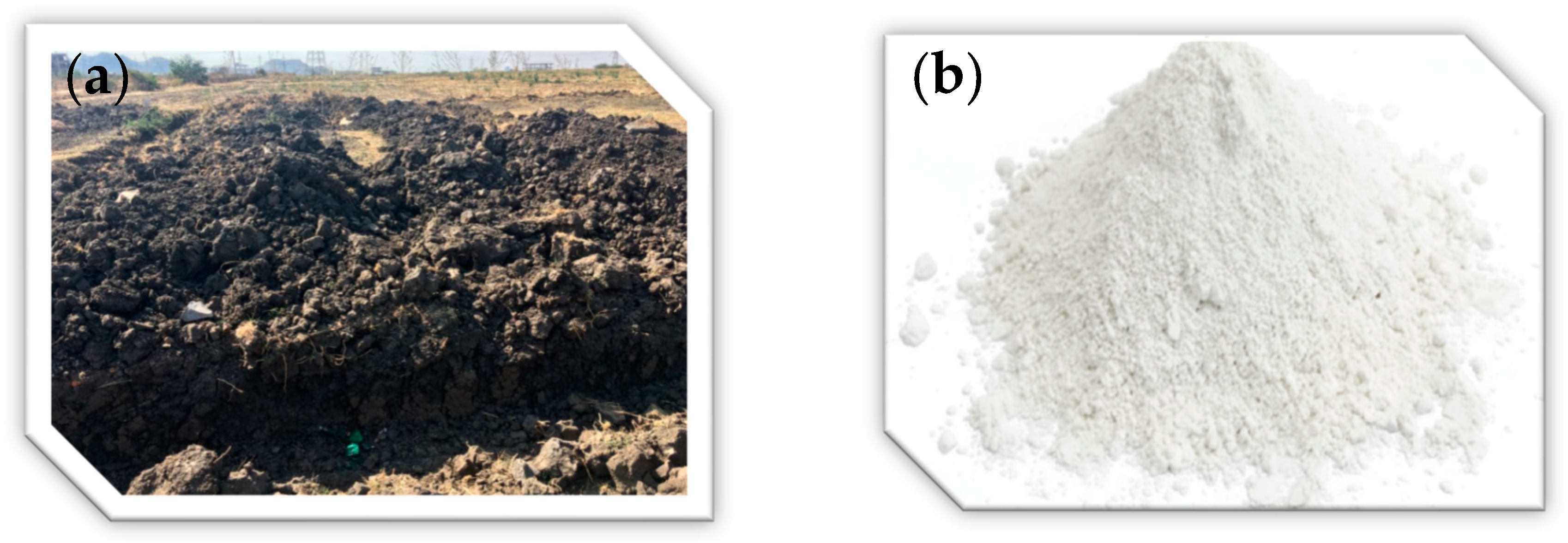

Two representative soils (

Figure 1) were selected to reflect distinct geotechnical challenges commonly encountered in mining and civil works: Black Cotton Soil (denoted as BC), Kaolinite Clay (denoted as KC)

Each soil sample was air-dried, pulverised, and then passed through a 2 mm sieve before characterisation. Key index properties (particle size distribution, Atterberg limits, specific gravity, and swelling potential) were determined in accordance with IS 2720 [

9,

10,

11,

12]. The soil classification and baseline strength behaviour serve as control references for assessing the performance of glass-treated mixes.

Post-consumer soda–lime glass, obtained from discarded bottles and containers, was used as the primary Supplementary Material in this study (

Figure 2). The waste glass was first subjected to cleaning and sorting to remove labels, organic residues, and other contaminants. This was followed by mechanical crushing using a jaw crusher and subsequent fine grinding in a ball mill to achieve the required fineness. The ground material was sieved through a 75 µm mesh to limit the maximum particle size to ≤75 µm. The finely ground waste glass exhibits measurable pozzolanic activity only when the particles are reduced to a size of ≤75 µm [

3,

7,

8]. The processed glass powder was then characterised for its physical and chemical attributes.

2.1. Mix Design and Sample Preparation

GP was blended with soils at five different contents by dry weight of soil: 0% (control), 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%. Each mix was thoroughly homogenised using a mechanical mixer for 10 min to ensure uniform distribution.

For each soil–glass blend, the moisture–density relationship was established using the standard Proctor test in accordance with IS:2720 (Part 7) under light compaction conditions to determine the optimum moisture content (OMC) and maximum dry density (MDD). These parameters formed the basis for specimen preparation, ensuring consistency and a realistic field simulation. The soil Compaction Process followed in this study is illustrated in

Figure 3.

All cylindrical and compacted samples intended for subsequent testing—namely, unconfined compressive strength (UCS), California Bearing Ratio (CBR), and swelling index—were prepared at or near the determined OMC and compacted to 98% of the corresponding MDD, reflecting typical field compaction levels employed in mining backfill and road base stabilisation works. The use of 98% Standard Proctor MDD is consistent with established specifications for mining and road-base construction. Heavy-haul mining roads typically require ≥98% MDD to achieve the stiffness and rutting resistance needed for large payload trucks [

13]. Similarly, major pavement standards—IRC:37-2018 [

14], AASHTO T-180 [

15], and Austroads AGPT-08 (2017) [

16]—prescribe 97–100% MDD for stabilised subbase and base layers. Thus, the compaction level adopted in this study is aligned with internationally accepted field practice.

To more accurately replicate field conditions, particularly the operational lag between moist mixing and placement, the conditioned soil–glass mixtures were allowed to rest for a controlled period of approximately two hours prior to compaction. This resting period is crucial for simulating real-world construction scenarios involving transportation and laydown delays, allowing for uniform moisture distribution and partial reaction initiation between the glass powder and the soil matrix. All compacted specimens were demoulded after 24 h under controlled laboratory conditions. Following demoulding, the samples were transferred to a curing chamber maintained at a temperature of 27 ± 2 °C and a relative humidity of 60 ± 5%. These environmental conditions were kept constant for all tests to ensure uniform curing behaviour and reproducibility across specimens.

2.2. Experimental Tests

The basic index and physical properties of the soils were determined in accordance with IS:2720. Particle size distribution (PSD) was obtained using sieve analysis for particles larger than 75 µm and hydrometer analysis for finer particles. Specific gravity (Gs) was measured using a pycnometer (IS: 2720, Part 3) [

9]. Atterberg limits—including liquid limit (LL), plastic limit (PL), and plasticity index (PI)—were determined using the Casagrande apparatus and rolling method (IS:2720, Part 5) [

10]. Swelling characteristics were evaluated using the Differential Free Swell Index (DFSI) test (IS: 2720, Part 40) [

11], which measures the volumetric expansion of expansive soils when submerged in water. The experimental arrangement used for determining the Differential Free Swell Index is shown in

Figure 4.

The compaction characteristics of each glass–soil blend were determined through standard light compaction tests (IS: 2720, Part 7) [

17], which established the relationship between moisture content and dry density, and identified the optimum moisture content (OMC) and maximum dry density (MDD). Strength and bearing capacity were evaluated using the unconfined compressive strength (UCS) and California Bearing Ratio (CBR) tests. UCS tests were performed on cylindrical specimens (38 mm diameter × 76 mm height) in line with IS:2720 (Part 10) [

18]. Triplicate specimens were tested for each mix to ensure reliability and accuracy. CBR tests were conducted in accordance with IS:2720 (Part 16) [

19] under unsoaked conditions.

To ensure consistency, all strength and swelling tests were conducted after defined curing periods. UCS Samples were tested after 7 days of curing in accordance with IS 2720 (Part 10) [

18]. Unsoaked CBR tests were performed after 4 days of curing, consistent with IS 2720 (Part 16) [

19]. DFSI tests were performed immediately after sample preparation, following IS 2720 (Part 40) [

11], because DFSI reflects inherent swell potential rather than time-dependent strength gain. The strain rate for UCS testing was maintained at 1.25 mm/min. For all UCS, CBR, and DFSI tests, three parallel specimens (n = 3) were prepared and tested. The mean and standard deviation values are reported in the Results section. All test results represent mean values based on triplicate specimens to ensure accuracy and reproducibility. The laboratory setups for both the Unconfined Compressive Strength (UCS) test and the California Bearing Ratio (CBR) test are shown in

Figure 5.

2.3. Energy Accounting

A Key objective of this study was to establish a direct relationship between mechanical performance improvements and the energy consumption associated with material production and stabilisation activities. Strength–dosage curves were developed to evaluate the response of the soil to varying levels of glass powder (GP), allowing identification of the optimum GP content that delivers the most significant strength enhancement per unit of energy invested. The total Energy Investment (EI) for GP-stabilised mixes was computed by summing the energy required for (i) crushing and grinding during GP production (kWh per tonne of material), (ii) mixing and compaction per unit volume of treated soil, and (iii) the comparative baseline energy required to achieve equivalent strength using conventional stabilisers such as cement or lime [

1]. Based on XRF-derived chemistry (

Table 1), the high amorphous silica content (≈70%) of the glass powder contributes to its reactivity despite its low embodied energy (≈0.6 GJ/t).

To enable performance benchmarking across different stabilisation strategies, an Energy Performance Index (EPI) was defined as:

where

ΔUCS—represents the improvement in unconfined compressive strength relative to the untreated control soil. This index quantifies the strength gained per unit of energy input, allowing for a direct and meaningful comparison of alternative stabilisation strategies in terms of energy efficiency.

Furthermore, carbon emissions associated with each stabilisation scenario were estimated using known CO

2 emission factors for electricity generation and cement/lime production [

1,

2,

6]. This allowed for the calculation of net CO

2 savings achievable for each GP dosage level, establishing a clear link between mechanical performance, embodied energy, and environmental impact. This integrated energy accounting framework directly supports energy optimisation at production stages in mining, aligning with the principles of the circular economy and low-carbon construction.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterisation of Soil

The geotechnical characterisation results of the two soils are presented in

Table 2. Black Cotton (BC) soil exhibits a liquid limit (LL) of 76% and a plasticity index (PI) of 50%, reflecting high plasticity and expansive behaviour typical of montmorillonite-rich CH soils. In contrast, Kaolinite Clay (KC) has an LL of 45% and PI of 18%, thus classifying it as CI. This apparent difference reflects the underlying mineralogical composition: montmorillonite in BC has a higher specific surface area and water adsorption capacity, whereas kaolinite in KC is characterised by a stable 1:1 layer structure and lower cation exchange capacity, resulting in lower plasticity and reduced swelling potential [

20].

The Differential Free Swell Index (DFSI) values of 54% for BC and 12% for KC further emphasise this contrast. The high DFSI value for BC corresponds to its expansive nature and significant volumetric change upon wetting. In contrast, the low DFSI value for KC is typical of non-expansive kaolinitic soils. These variations have direct implications for energy consumption during stabilisation and compaction processes. Expansive soils require higher compaction energy and often higher stabiliser dosages to control volume change and achieve the target mechanical performance.

The specific gravity (Gs) of both soils was measured as 2.6, indicating the absence of organic contaminants or lightweight particles. Compaction characteristics show that BC has an optimum moisture content (OMC) of 20% and a maximum dry density (MDD) of 16 kN/m

3, whereas KC has a higher OMC of 25% and a lower MDD of 15 kN/m

3. This is consistent with their mineralogical and textural differences: kaolinite, being finer and less active, requires more moisture to achieve lubrication and particle rearrangement, whereas BC soils reach peak density at lower moisture contents due to their higher activity and finer but more reactive fabric [

21].

The unconfined compressive strength (UCS) of BC and KC was measured as 55 kN/m2 and 41 kN/m2, respectively. These values are within the typical range for untreated soft clays compacted near OMC. Similarly, unsoaked California Bearing Ratio (CBR) values of 7% for BC and 6% for KC are realistic for fine-grained cohesive soils without any chemical stabilisation.

Particle size distribution indicates a high clay fraction of 69% in BC and 62% in KC, confirming their fine-grained nature. These high fines content significantly influences the energy required for soil treatment, as increased plasticity and water retention in BC typically necessitate higher compaction and mixing energy. In contrast, lower plasticity in KC corresponds to lower energy demand during production and placement. Thus, understanding these baseline geotechnical properties is crucial for accurately quantifying energy input during stabilisation and optimising material selection for sustainable infrastructure and mining applications.

3.2. Characterisation of Glass Powder

The quantitative X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF) results revealed that the glass powder consists predominantly of amorphous SiO

2 (≈73%), followed by Na

2O (≈13%), CaO (≈9%), Al

2O

3 (≈3%), and Fe

2O

3 (≈1%). This composition matches typical soda–lime glass chemistry and explains the mild pozzolanic reactivity observed. The oxide distribution is presented in

Table 2. Such a high proportion of amorphous silica supports the potential of GP to participate in secondary C–S–H gel formation when blended with clay minerals.

The specific gravity, measured using a pycnometer in accordance with IS: 2720 (Part 3) [

9], was approximately 2.6, indicating a dense and stable particle structure. Particle size analysis (

Figure 6), as per IS 2720 Part IV [

12], revealed that the majority of the particles were distributed in the 10–80 µm range, corresponding to the silt to fine-silt fraction, which enhances reactivity and blending behaviour in soil matrices. X-ray diffraction (XRD) confirmed the predominantly amorphous structure of the material, which is favourable for pozzolanic activity when used as a stabiliser.

Unlike energy-intensive binders such as cement and lime, glass powder is a secondary product obtained through the crushing and grinding of post-consumer glass waste from existing manufacturing and recycling streams. As a result, its embodied energy is substantially lower, since no high-temperature calcination or clinker production is involved. This low energy requirement, coupled with its reactive amorphous structure and waste-derived origin, makes glass powder an attractive, sustainable binder for geotechnical and mining infrastructure applications.

3.3. Plasticity Characteristics

The results presented in

Table 3 and

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 clearly demonstrate that the incorporation of glass powder (GP) has a pronounced influence on the plasticity characteristics of both Black Cotton (BC) soil and Kaolinite Clay (KC). A systematic and monotonic reduction in the liquid limit (LL) and plasticity index (PI) is observed with increasing GP content, while plastic limit (PL) shows only marginal variation. This trend is attributed primarily to the inert and non-plastic nature of GP, which dilutes the active clay mineral fraction, thereby reducing the soil’s capacity to absorb and retain water within its diffuse double layer.

For BC soil, characterised by high initial plasticity due to the predominance of montmorillonitic minerals, the LL decreases from 76% at 0% GP to 61% at 20% GP. This reduction (~20%) aligns with previously reported values for expansive soils stabilised using finely ground inert materials such as waste glass, fly ash, and quarry dust [

5,

21]. The plastic limit, on the other hand, shows only a minor decrease (25% to 21%), suggesting that the plastic state moisture content of expansive soils is less sensitive to GP replacement compared to the liquid limit. The plasticity index (PI) reduces from 51% to 40%, indicating a significant decrease in soil plasticity and, consequently, in potential volumetric changes and moisture sensitivity.

For KC, the LL declines from 45% to 32% (a reduction of ~29%), reflecting a sharper relative decrease compared to BC. This is expected because kaolinite, being a 1:1 mineral with a lower specific surface area and limited swelling capacity, exhibits a greater proportional influence of GP dilution. Similarly, PI decreases from 19% to 12%, reflecting a reduction of ~37%. These reductions are within the higher range of values reported for kaolinite-rich soils stabilised with fine inert additives [

4]. The slightly more pronounced response in KC is consistent with its lower initial plasticity and weaker electrochemical bonding, which allows GP particles to effectively occupy interparticle spaces, thereby reducing the water retained in both liquid and plastic states.

An important observation is the plateauing of LL and PI beyond 15–20% GP content for both soils. This behaviour suggests the existence of an optimal replacement level, beyond which additional GP does not contribute significantly to plasticity reduction.

The reduced plasticity not only improves workability and strength but also results in lower energy consumption during field mixing and compaction operations, as less water is required to achieve the target moisture content. This is directly relevant to the energy optimisation objectives of mining and infrastructure projects in resource-intensive sectors. From an energy perspective, the reduction in moisture requirement translates into decreased energy expenditure in soil processing—particularly for drying, mixing, and compaction—thereby contributing to more sustainable and energy-efficient construction practices.

3.4. Compaction Characteristics

The variation in optimum moisture content (OMC) and maximum dry density (MDD) with increasing glass powder (GP) content provides critical insight into the compaction behaviour of both Black Cotton (BC) soil and Kaolinite Clay (KC). As shown in

Table 4 and

Figure 10 and

Figure 11, the OMC of BC soil decreases from 20% at 0% GP to 16% at 20% GP, while the MDD increases from 16 kN/m

3 to 18.5 kN/m

3. A similar trend is observed for KC, where the OMC reduces from 25% to 19%, accompanied by an increase in MDD from 15 kN/m

3 to 16.7 kN/m

3.

The observed decrease in OMC with GP incorporation can be attributed to the inert and non-absorptive nature of glass powder, which reduces the water-holding capacity of the soil–binder matrix. Unlike expansive clay minerals such as montmorillonite, glass particles do not retain significant amounts of water within their structure. As a result, less water is required to achieve the same compaction energy and maximum density. This behaviour has been consistently reported in previous stabilisation studies using inert fine materials, such as fly ash, quarry fines, and recycled glass powder [

4,

22].

The increase in MDD is primarily due to the void-filling effect of fine glass particles, which improves the particle packing arrangement and minimises air voids within the soil structure. The angular and smooth morphology of GP enhances the mechanical interlocking and densification during compaction. For BC soil, this effect is particularly pronounced, with a 15.6% increase in MDD over the control at 15% GP. In KC, the increase is more moderate (approximately 11.3%), reflecting the differences in initial soil structure and mineralogy. Since kaolinite is less expansive and has a relatively lower surface activity, the contribution of GP to densification is less dramatic than in highly plastic BC soils.

A notable feature of the compaction curves is the progressive decrease in OMC, coupled with an increase in MDD, up to the optimum GP content (approximately 15%), followed by a slight plateau at 20%. This indicates that at lower GP dosages, the filler effect dominates, improving soil fabric and density. Beyond a certain replacement threshold, additional GP leads to marginal or no further improvement, as the system approaches maximum achievable densification for the given compaction energy. This plateau behaviour is consistent with stabilisation mechanisms dominated by physical effects rather than chemical reactions, particularly under ambient curing conditions [

23].

From an energy-efficiency standpoint, the reduction in OMC and the simultaneous increase in MDD have practical implications. Lower water demand during compaction reduces mixing and moisture-conditioning energy, while achieving a higher dry density translates to enhanced load-bearing capacity and reduced thickness of structural layers. This is especially relevant in mining and infrastructure backfilling applications, where material processing energy constitutes a significant fraction of the total energy footprint. Thus, incorporating GP as a stabiliser contributes not only to improved engineering performance but also to reduced embodied energy and carbon emissions during the production stage.

3.5. Unconfined Compressive Strength

The unconfined compressive strength (UCS) results presented in

Table 5 and

Figure 12 show a distinct and systematic improvement in the mechanical performance of both Black Cotton (BC) and Kaolinite Clay (KC) soils with increasing glass powder (GP) content up to an optimum level, followed by a marginal decline beyond it. The untreated BC and KC soils exhibited baseline strengths of 55 kN/m

2 and 41 kN/m

2, respectively. With the incorporation of GP, a steady increase in UCS was observed, reaching 67 kN/m

2 and 53 kN/m

2 at 5% GP, and further improving to 80 kN/m

2 and 73 kN/m

2 at 10% GP for BC and KC, respectively. The maximum UCS values of 95 kN/m

2 for BC and 100 kN/m

2 for KC were achieved at 15% GP, indicating an optimum stabiliser dosage beyond which a slight reduction in strength occurred; 20% GP mixes showed UCS values of 92 kN/m

2 and 94 kN/m

2.

The strength development trend follows the typical parabolic response reported in the literature for fine-grained soils stabilised with supplementary mineral or inert admixtures, where a balance between densification, improved interparticle friction, and matrix dilution effects governs strength gains. The continuous increase up to 15% GP can be attributed to microstructural refinement and enhanced packing efficiency, as GP reduces void ratios and promotes a denser soil skeleton [

5,

22]. The concurrent reduction in liquid limit and plasticity index, as discussed earlier, reflects a lower water affinity and improved structural rigidity, both of which contribute to an enhanced load-bearing capacity. The angular and rigid GP particles likely act as micro-reinforcements, improving interlocking and internal friction within the soil matrix. At the same time, the ultra-fine fraction serves as a micro-filler, refining pore structure and stress transmission paths.

The slight decline in UCS beyond 15% GP suggests that excessive replacement may disrupt the clay fabric and reduce cohesive bonding between particles, leading to reduced load transfer efficiency. Nonetheless, the overall improvement—from 55 kN/m2 to 95 kN/m2 in BC and from 41 kN/m2 to 100 kN/m2 in KC—represents a substantial enhancement in strength with minimal embodied energy input. This is particularly significant when viewed through the lens of energy efficiency. Since GP is a recycled by-product with low production energy, the observed gains correspond to a high Energy Performance Index (EPI), representing greater strength gain per unit of energy invested. Moreover, the lower optimum moisture content and higher dry density achieved at the same GP levels reduce energy requirements during mixing and compaction, further improving sustainability.

Overall, the UCS behaviour demonstrates that incorporating glass powder significantly improves the mechanical and energy performance of both expansive and low-plasticity soils, with the optimum stabilisation effect occurring at approximately 15% GP content. These results reinforce the potential of GP as an energy-efficient and sustainable stabiliser for subgrades, backfills, and other geotechnical applications relevant to the mining and infrastructure sectors.

3.6. Unsoaked California Bearing Ratio (CBR)

The California Bearing Ratio (CBR) results presented in

Table 6 and

Figure 13 demonstrate a clear and systematic improvement in the load-bearing capacity of both Black Cotton (BC) and Kaolinite Clay (KC) soils with the addition of glass powder (GP), followed by a slight decline beyond the optimum dosage. The untreated BC and KC soils exhibited baseline CBR values of 7% and 6%, respectively. With the inclusion of 5% GP, these values increased to 11% and 9%, indicating the onset of measurable improvement in subgrade strength. A further increase in GP content to 10% and 15% led to significant gains, with CBR values peaking at 20% for BC and 15% for KC at 15% GP. At a 20% GP, a marginal reduction was observed, with CBR values decreasing to 18% (BC) and 13% (KC), suggesting that the optimum GP dosage for maximum bearing capacity lies around 15%.

This behaviour closely mirrors the parabolic strength trend observed earlier for UCS, where strength increased with GP content up to an optimal level and then declined slightly thereafter. Such a response is well-documented in stabilisation studies involving inert or supplementary mineral admixtures [

4]. The increase in CBR values can be attributed to several complementary mechanisms. Firstly, the addition of GP leads to improved densification of the soil matrix, as reflected in the increased maximum dry density values, which enhances penetration resistance under load. Secondly, the reduction in plasticity—indicated by a decrease in liquid limit and plasticity index with increasing GP content—results in lower moisture susceptibility and greater interparticle friction. Thirdly, the angular shape and rigid nature of the GP particles improve interlocking between soil grains, further enhancing the bearing capacity [

5].

The peak CBR values achieved at 15% GP (20% for BC and 15% for KC) are particularly noteworthy. These values represent nearly a threefold improvement compared to the untreated soils, effectively elevating their performance category from weak subgrade to a level suitable for lightly to moderately trafficked pavement structures and mine haul roads. The slightly higher improvement in BC relative to KC is expected, as expansive BC soils typically offer greater scope for strength enhancement through stabilisation. The decline at a 20% GP likely arises from the excessive dilution of the clay matrix by inert particles, which reduces cohesion and impairs load transfer [

4,

5].

In summary, the enhancement of CBR values with increasing GP content reinforces the earlier findings from plasticity and UCS tests, highlighting the synergistic effects of GP on soil behaviour. The optimum dosage of 15% GP provides the best balance between strength improvement and material efficiency, making it a promising sustainable stabiliser for subgrade improvement, mine haul roads, and infrastructure applications.

3.7. Differential Free Swell Index (DFSI)

The Differential Free Swell Index (DFSI) results reveal a clear and consistent reduction trend with increasing glass powder content for both Black Cotton (BC) soil and Kaolinite Clay (KC), indicating a positive effect of glass powder on mitigating the expansive behaviour of fine-grained soils. As shown in

Figure 14 and

Table 7, the DFSI decreased from 54% to 30% for BC and from 12% to 3% for KC with the incorporation of 20% GP. This progressive reduction aligns with typical responses reported in the literature for treatments involving pozzolanic or non-plastic fine additives, which act by improving soil gradation, reducing double-layer thickness, and decreasing swell potential through pozzolanic reaction and mechanical interlocking effects [

22,

24].

The larger initial DFSI of BC compared to KC reflects the inherently higher montmorillonitic content of black cotton soils, which exhibit greater water absorption and swelling capacity. In contrast, kaolinitic clays have lower specific surface area and weaker water retention capacity, resulting in significantly lower initial DFSI values. The gradual decline with increasing GP content is attributed to the filling and binding action of fine glass powder, which reduces the void ratio and moisture affinity of the soil matrix, thereby limiting its capacity for volume expansion. Additionally, the partial pozzolanic reactivity of amorphous silica in the GP leads to the formation of cementitious gels (C–S–H and C–A–S–H), which enhance the inter-particle bonding and stabilise the soil fabric.

Figure 15 clearly demonstrates that at a 20% GP, the DFSI reduction reached approximately 45% for BC and 75% for KC relative to the untreated baseline. This level of improvement is comparable to reductions achieved with fly ash, slag, and other supplementary binders reported in recent studies [

25].

Figure 15 effectively illustrates both the absolute DFSI values and the relative percentage reduction, making it easier to interpret the stabilisation efficiency and optimum dosage. From a practical standpoint, such significant reductions in swelling potential directly translate to lower heave pressures and enhanced subgrade stability, which is particularly beneficial in mining haul roads, backfill zones, and foundations in expansive soil regions, thereby reducing the maintenance energy and embodied carbon associated with repairs.

3.8. Energy Accounting

A key objective of this study was to establish a quantitative relationship between mechanical enhancement and energy consumption associated with the use of waste glass powder (GP) as a sustainable soil stabiliser. This dual framework allows performance-based design decisions to be coupled with energy efficiency and carbon accounting, thereby supporting low-energy ground improvement strategies in mining and infrastructure projects.

3.8.1. Energy Investment (EI) and Performance Relationship

The total energy investment (EI) for each GP dosage was computed as the sum of three components:

where

= energy for crushing and grinding waste glass into powder (kWh/t),

= energy for mixing operations per unit volume,

= energy consumed during compaction to 98% MDD.

Typical values from industrial and academic databases were considered for energy factors. Cement production typically consumes 3.5–4.5 GJ/t, while glass powder production (crushing and grinding) requires approximately 0.5–0.6 GJ/t [

1,

2,

6,

26]. Mixing and compaction energy in field operations is comparatively low, ranging from 0.15 to 0.25 GJ/t, typical of light compaction used in subgrade stabilisation [

1,

2,

6,

26].

For example, considering 15% GP replacement:

This represents an energy saving of nearly 85% compared to equivalent cement stabilisation.

Figure 16 illustrates the energy flow, beginning with waste collection and GP processing, followed by mixing, compaction, and performance evaluation. This systematic representation provides a transparent basis for quantifying embodied energy and emissions at each stage.

It is acknowledged that this study did not include cement- or lime-stabilised mechanical control mixes. Consequently, the energy comparison utilises cement/lime embodied energy benchmarks from established literature, consistent with previous low-carbon stabilisation studies. The aim here is to assess the strength-per-unit-energy performance of GP, rather than its absolute equivalence to cement or lime. While UCS and unsoaked CBR provide robust short-term indicators, long-term durability tests (e.g., wet–dry, freeze–thaw, sulphate resistance) were beyond the current scope. These limitations are recognised, and future work will incorporate complete cement/lime control tests and durability assessments to strengthen engineering applicability.

3.8.2. Energy Performance Index (EPI)

To link the energy consumption with mechanical performance, an Energy Performance Index (EPI) was defined as:

where

= gain in unconfined compressive strength relative to untreated soil (kN/m2),

= total energy input (kWh/t).

For BC soil at 15% GP, UCS increased from 55 to 95 kN/m

2 (ΔUCS = 40 kN/m

2).

For KC soil at 15% GP, UCS increased from 41 to 100 kN/m

2 (ΔUCS = 59 kN/m

2):

The results presented in

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 indicate that GP stabilisation not only improves mechanical performance but also achieves a high strength-to-energy ratio, particularly for KC soil. Notably, if cement were used instead, the same strength increase would require approximately 5–6 times more embodied energy [

5,

6].

3.8.3. Carbon Emission Reduction

To illustrate the comparative energy and carbon benefits of GP over cement, a sensitivity analysis was conducted for stabilisation dosages of 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% (by mass of soil). Energy intensities were taken from mid-range literature values: Cement 4.0 GJ/t of stabiliser; GP 0.6 GJ/t of stabiliser (crushing + grinding only). Carbon emission factors used: Cement 0.09 kg CO

2/MJ; GP 0.02 kg CO

2/MJ.

Sample calculations are shown below.

Energy per tonne of treated soil

(b) Glass powder (GP), 15% dosage

CO

2 emissions per tonne of treated soil

Net Saving per tonne of treated soil

Sensitivity analysis of energy and carbon emissions for cement and GP stabilisation at different dosages is presented in

Table 8.

At 15% dosage (corresponding to optimum strength performance in this study), cement stabilisation requires approximately 600 MJ/t of soil, while GP requires only 90 MJ/t, representing an 85% energy reduction. Carbon emissions drop from 54 kg CO

2/t for cement to 1.8 kg CO

2/t for GP, resulting in a net reduction of 52.2 kg CO

2/t (

Figure 19). The savings remain consistent across dosages, highlighting the robustness of the GP advantage. These reductions scale significantly in large-scale mining and infrastructure applications, where treated volumes reach hundreds of thousands of tonnes.

This coupling of mechanical, energy, and carbon performance provides a rational basis for selecting the optimum dosage in engineering design. For example, a 15% GP dosage corresponds to peak mechanical performance and the lowest EPI denominator (EI), and the EPI advantage over cement exceeds 4–6 times, depending on the soil type.

3.8.4. Implications for Mining Infrastructure and Circular Economy

The integrated energy–performance framework highlights that waste glass powder can provide equivalent or superior stabilisation effects at a fraction of the energy and carbon cost of conventional binders. For large mining operations—such as haul roads, embankments, or backfilled stopes—this translates to:

Reduced embodied energy,

Significant CO2 mitigation,

Improved mechanical reliability, and

Economic savings due to reduced material and operational costs.

This aligns directly with the energy transition and decarbonisation goals of the mining sector, supporting SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and SDG 13 (Climate Action).

While the present study establishes the mechanical–energy–carbon performance of GP-stabilised soils from a laboratory perspective, practical field deployment requires an evaluation of the process and cost implications. GP stabilisation offers operational advantages such as lower moisture demand, reduced compaction effort, and the ability to utilise locally generated glass waste streams, which can decrease hauling and material procurement costs. In mining haul-road and backfilling operations—where stabilised volumes commonly exceed 50,000–200,000 m3—these reductions can translate into substantial savings in fuel use, equipment hours, and layer-thickness requirements. Moreover, GP production involves only mechanical crushing and grinding, enabling on-site or near-site processing with relatively simple equipment, lowering both capital and operational costs compared to cement or lime plants. Although a full cost–benefit analysis is beyond the scope of this study, the demonstrated reduction in embodied energy and CO2 intensity, combined with the potential for local sourcing and simplified logistics, indicates strong practical feasibility for large-scale mining applications. Future studies should incorporate field trials, detailed process flows, and life-cycle cost analysis to enable more robust engineering and economic decision-making.

4. Conclusions

This study developed an integrated mechanical–energy–carbon framework to evaluate waste glass powder (GP) as a low-carbon stabiliser for black cotton (BC) and kaolinite clay (KC) soils. The findings confirm that GP provides meaningful engineering benefits while significantly lowering embodied energy relative to cement.

- (1)

Plasticity and compaction:

GP reduces the liquid limit, plasticity index, and optimum moisture content, while increasing dry density through filler and fabric refinement effects. These changes enhance workability and lower the energy demand associated with mixing and compaction operations.

- (2)

Strength and bearing capacity:

UCS improved by up to 73% and CBR nearly tripled at an optimum dosage of 15% GP for both soils. The improvement arises from denser packing, reduced water affinity, and partial pozzolanic interaction with soil minerals.

- (3)

Swell control:

DFSI decreased by 45–75%, indicating substantial mitigation of expansive behaviour—crucial for mining haul roads and foundation layers constructed on BC soils exposed to moisture fluctuations.

- (4)

Energy and carbon performance:

GP stabilisation achieved approximately 85% lower embodied energy and approximately 52 kg CO2/t lower emissions than cement. The Energy Performance Index demonstrated that GP yields higher strength per unit of energy invested by a factor of 4–6 at the same dosage, positioning it as a highly efficient stabiliser for low-carbon ground improvement.

The combined mechanical and energy outcomes demonstrate that GP is not merely a partial cement substitute but a genuinely low-carbon stabilisation pathway with direct applicability to mining backfills, haul roads, and infrastructure platforms. Its ability to reduce water demand, improve density, and minimise embodied energy yields cumulative benefits at the field scale.

Long-term durability (wet–dry, freeze–thaw, and sulphate resistance) and field-scale validation were beyond the scope of the present study. Incorporating these assessments, along with direct cement/lime control mixes, will further strengthen the engineering design basis.

Overall, the proposed mechanical–energy–carbon framework provides a more holistic basis for evaluating low-carbon stabilisers than traditional strength-only approaches. By linking engineering performance with embodied energy and CO2 reduction, this study demonstrates that GP offers not just mechanical improvement but a quantifiable sustainability advantage. These insights provide a clearer basis for decision-making in field deployment, supporting the large-scale adoption of GP stabilisation in mining infrastructure.