Comparing Ecuadorian Cocoa Mucilage-Based Bio-Ethanol and Commercial Fuels Toward Their Performance and Environmental Impacts in Internal Combustion Engines

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Material and Experimental Methodological Scheme

2.2. Fermentation, Distillation, and Physicochemical Preparation of the E5–CCN51 Blend

2.3. Energy and Exergy Analysis Model Applied to the Internal Combustion Engine

2.4. Static Exhaust Emission Tests

3. Results and Discussion

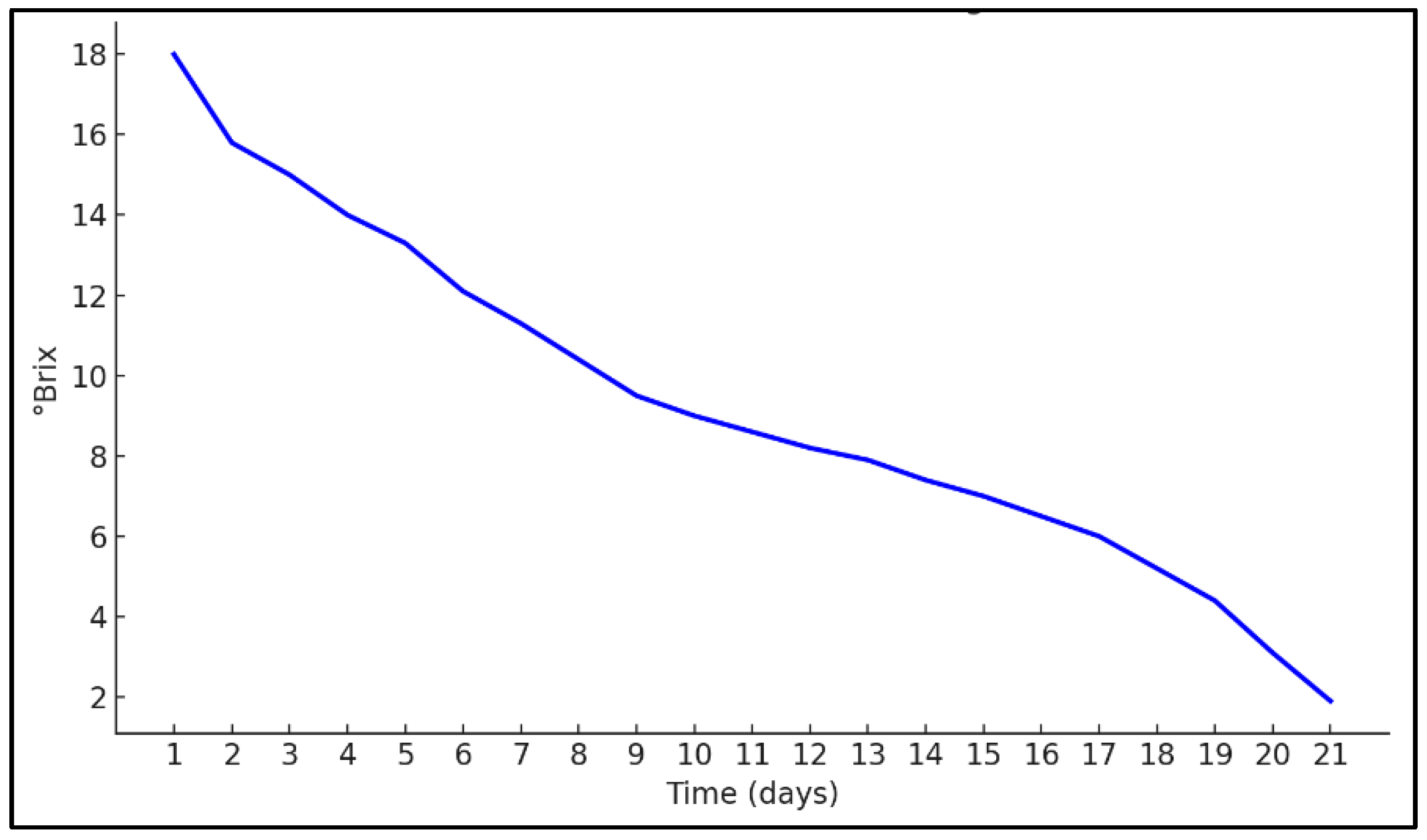

3.1. Fermentation and Distillation Performance of Cocoa Mucilage

3.2. Comparative Evaluation of the Physicochemical Properties of E5–CCN51 Blend and Commercial Fuels in Ecuador

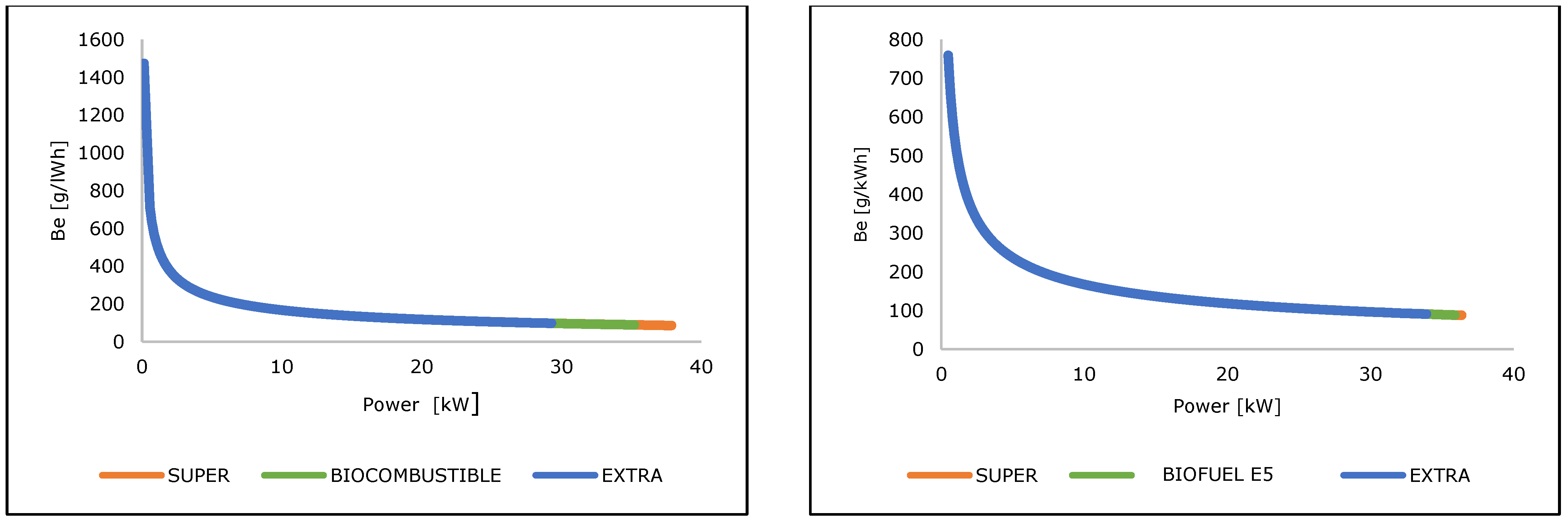

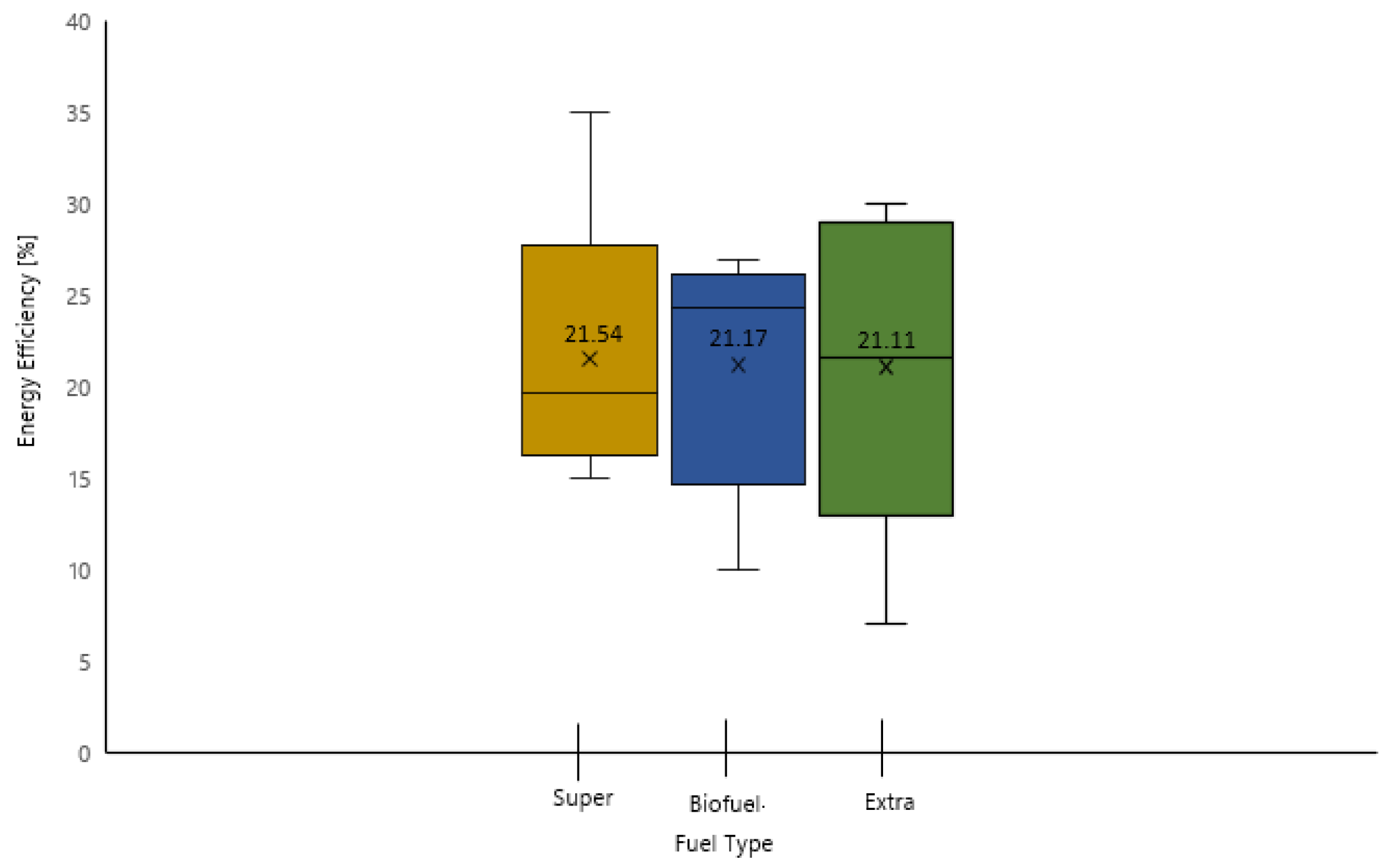

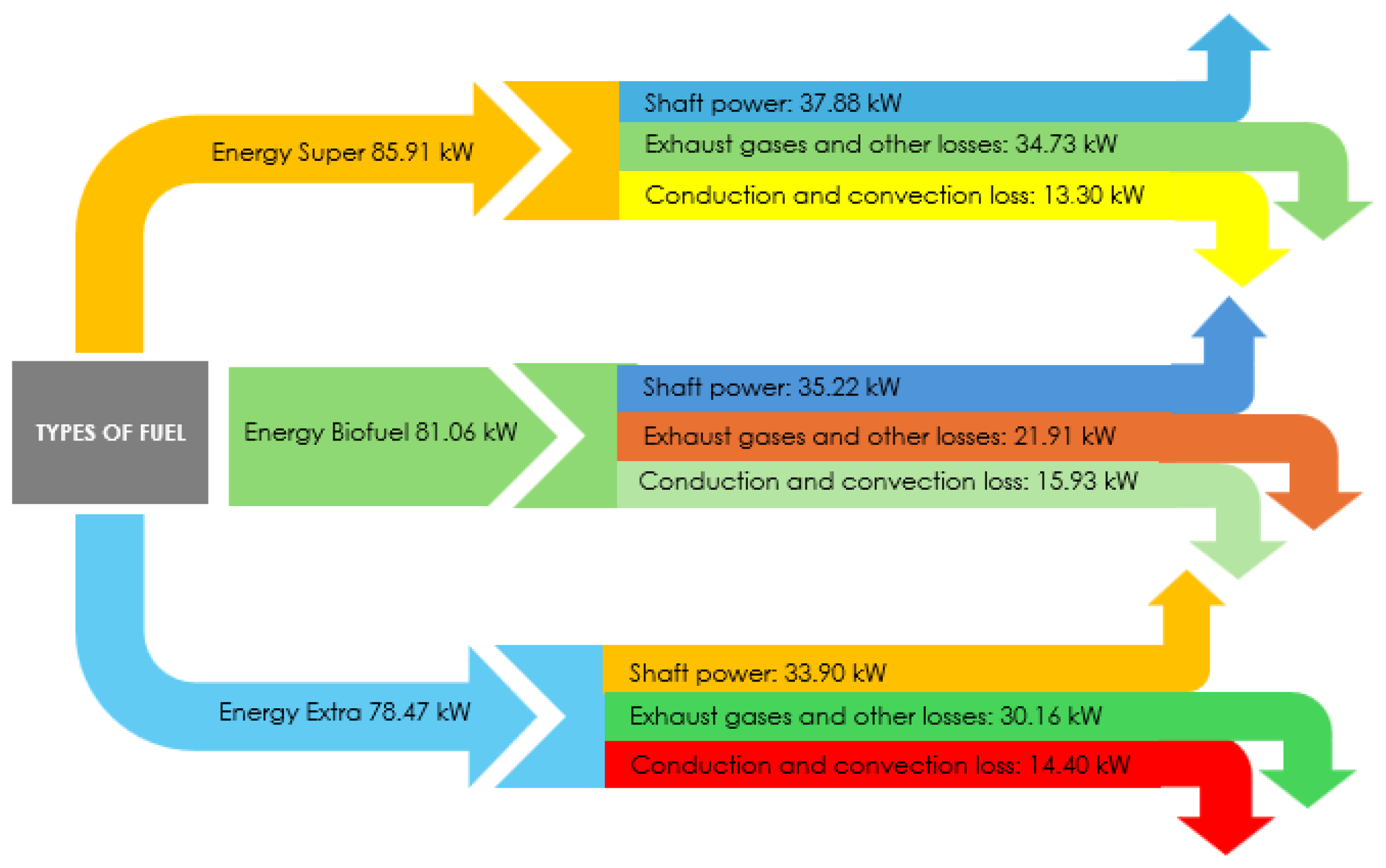

3.3. Energetic Performance Assessment Under Real Operating Conditions

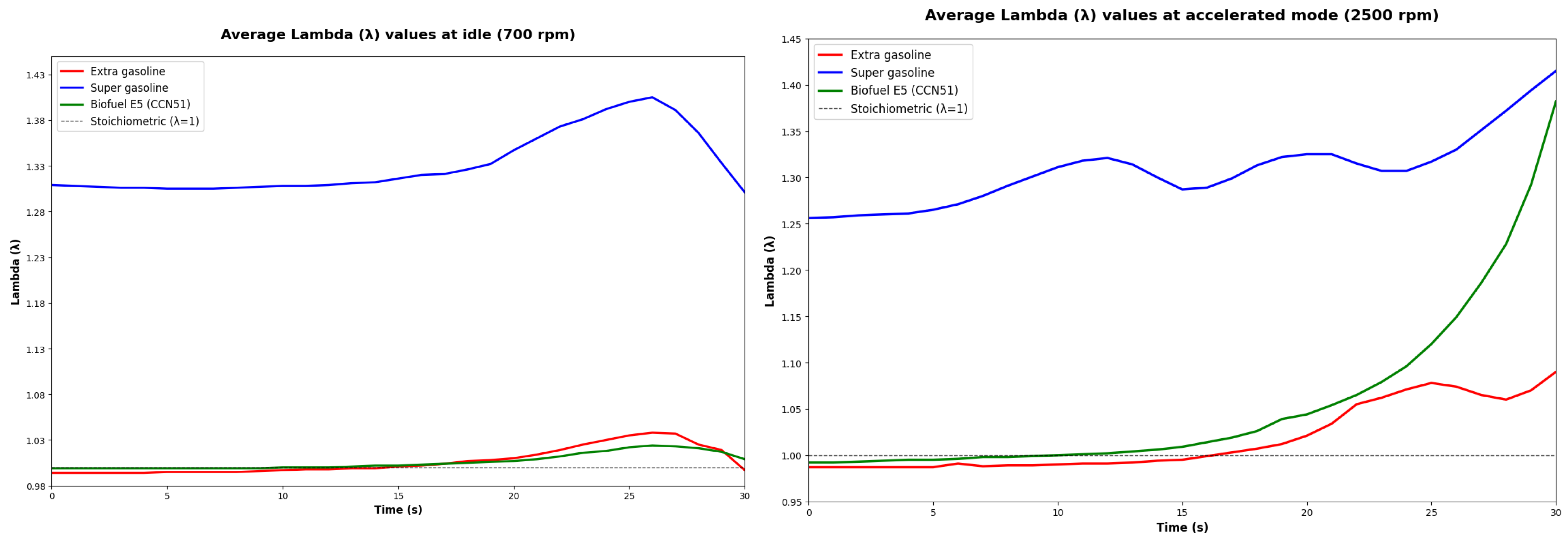

3.4. Evaluation of Environmental Parameters

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paulina, J.; Peter, N. Transport. In Climate Change 2022—Mitigation of Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 1049–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlingstein, P.; O’SUllivan, M.; Jones, M.W.; Andrew, R.M.; Hauck, J.; Landschützer, P.; Le Quéré, C.; Li, H.; Luijkx, I.T.; Olsen, A.; et al. Global Carbon Budget 2024. Earth Syst Sci Data 2025, 17, 965–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, A.; Valentim, B.; Prieto, A.C.; Noronha, F. Raman spectroscopy of coal macerals and fluidized bed char morphotypes. Fuel 2012, 97, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durbin, T.D.; Miller, J.W.; Younglove, T.; Huai, T.; Cocker, K. Effects of Fuel Ethanol Content and Volatility on Regulated and Unregulated Exhaust Emissions for the Latest Technology Gasoline Vehicles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 4059–4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorr, E.; Goldstein, B.; Aubry, C.; Gabrielle, B.; Horvath, A. Best practices for consistent and reliable life cycle assessments of urban agriculture. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 419, 138010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Ou, L.; Li, Y.; Hawkins, T.R.; Wang, M. Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Biodiesel and Renewable Diesel Production in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 7512–7521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canabarro, N.I.; Silva-Ortiz, P.; Nogueira, L.A.H.; Cantarella, H.; Maciel-Filho, R.; Souza, G.M. Sustainability assessment of ethanol and biodiesel production in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Guatemala. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 171, 113019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcentales, D.; Silva, C.; Ramirez, A.D. Environmental analysis of road transport: Sugarcane ethanol gasoline blend flex-fuel vs. battery electric vehicles in Ecuador. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2023, 118, 103718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; del Valle, A.; de la Fuente, A. Droughts worsen air quality and health by shifting power generation. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo-Silva, S.; Punina-Guerrero, D.; Rivera-Gonzalez, L.; Escobar-Segovia, K.; Barros-Enriquez, J.D.; Almeida-Dominguez, J.A.; del Castillo, J.A. Hydropower Scenarios in the Face of Climate Change in Ecuador. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrador, R.B.; Teles, B.A.d.S. Life cycle assessment of battery electric vehicles and internal combustion vehicles using sugarcane ethanol in Brazil: A critical review. Clean. Energy Syst. 2022, 2, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grijalva, E.R.; Martínez, J.M.L.; Flores, M.N.; Del Pozo, V. Design and Simulation of a Powertrain System for a Fuel Cell Extended Range Electric Golf Car. Energies 2018, 11, 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grijalva, E.R.; Martínez, J.M.L. Analysis of the Reduction of CO2 Emissions in Urban Environments by Replacing Conventional City Buses by Electric Bus Fleets: Spain Case Study. Energies 2019, 12, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laverde-Albarracín, C.; González, J.F.; Ledesma, B.; Román-Suero, S. Comparative Study of Thermochemical Valorization of CCN51 Cocoa Shells: Combustion, Pyrolysis, and Gasification. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffitzel, F.; Jakob, M.; Soria, R.; Vogt-Schilb, A.; Ward, H. Can government transfers make energy subsidy reform socially acceptable? A case study on Ecuador. Energy Policy 2020, 137, 111120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalakeviciute, R.; Diaz, V.; Rybarczyk, Y. Impact of City-Wide Diesel Generator Use on Air Quality in Quito, Ecuador, during a Nationwide Electricity Crisis. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, H.; Kaiser, D.; Pavón, S.; Molina, E.; Siguenza, J.; Bertau, M.; Lapo, B. Valorization of cocoa’s mucilage waste to ethanol and subsequent direct catalytic conversion into ethylene. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2022, 97, 2171–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, T.F.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. Cocoa By-Products: Characterization of Bioactive Compounds and Beneficial Health Effects. Molecules 2022, 27, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, A.M.; Botina, B.L.; García, M.C.; Cardona, W.A.; Montenegro, A.C.; Criollo, J. Dynamics of cocoa fermentation and its effect on quality. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Rodriguez, W.J.; Morante-Carriel, J.; Carranza-Patiño, M.; Ormaza-Vásquez, D.; Ayuso-Yuste, M.C.; Bernalte-García, M.J. Fermentation with Pectin Trans-Eliminase to Reduce Cadmium Levels in Nacional and CCN-51 Cocoa Bean Genotypes. Plants 2025, 14, 2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llerena, W.; Samaniego, I.; Vallejo, C.; Arreaga, A.; Zhunio, B.; Coronel, Z.; Quiroz, J.; Angós, I.; Carrillo, W. Profile of Bioactive Components of Cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) By-Products from Ecuador and Evaluation of Their Antioxidant Activity. Foods 2023, 12, 2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Noboa, J.; Bernal, T.; Soler, J.; Peña, J.Á. Kinetic modeling of batch bioethanol production from CCN-51 Cocoa Mucilage. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2021, 128, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Castro, R.; Guerrero, R.; Valero, A.; Franco-Rodriguez, J.; Posada-Izquierdo, G. Cocoa Mucilage as a Novel Ingredient in Innovative Kombucha Fermentation. Foods 2024, 13, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D1298-12b(2017)e1; Standard Test Method for Density, Relative Density, or API Gravity of Crude Petroleum and Liquid Petroleum Products by Hydrometer Method. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM D4814-22; Standard Specification for Automotive Spark-Ignition Engine Fuel. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASTM D7794-21; Standard Practice for Blending Mid-Level Ethanol Fuel Blends for Flexible-Fuel Vehicles with Automotive Spark-Ignition Engines. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- Chicaiza Intriago, J.G.; Zambrano Briones, G.E.; Delgado Villafuerte, C.R.; Ávila Martínez, M.F.; Pincay Cantos, M.F. Linear Correlation Analysis of Production Parameters of Biofuel from Cacao Theobroma cacao L.) Mucilage. J. Ecol. Eng. 2024, 25, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyago-Cruz, E.; Salazar, I.; Guachamin, A.; Alomoto, M.; Cerna, M.; Mendez, G.; Heredia-Moya, J.; Vera, E. Bioactive Compounds, Antioxidant, and Antimicrobial Activity of Seeds and Mucilage of Non-Traditional Cocoas. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D4809-18; Standard Test Method for Heat of Combustion of Liquid Hydrocarbon Fuels by Bomb Calorimeter (Precision Method). American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- ASTM D86; Standard Test Method for Distillation of Petroleum Products at Atmospheric Pressure. American Society for Testing and Materials ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- ASTM D323; Standard Test Method for Vapor Pressure of Petroleum Products (Reid Method). American Society for Testing and Materials ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- ASTM D4052; Standard Test Method for Density, Relative Density, and API Gravity of Liquids by Digital Density Meter. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- ASTM D445; Standard Test Method for Kinematic Viscosity of Transparent and Opaque Liquids (and Calculation of Dynamic Viscosity). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM D4294; Standard Test Method for Sulfur in Petroleum and Petroleum Products by Energy Dispersive X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometry. American Society for Testing and Materials ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- ASTM D381; Standard Test Method for Gum Content in Fuels by Jet Evaporation. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM D4815; Standard Test Method for Determination of MTBE, ETBE, TAME, DIPE, tertiary-Amyl Alcohol and C1 to C4 Alcohols in Gasoline by Gas Chromatography. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- NTE INEN 2102; Standard Test Method for Distillation of Petroleum Products at Atmospheric Pressure. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- NTE INEN 2102; Derivados del Petróleo. Gasolina. Determinación de las Características Antidetonantes. Método Research (RON). Servicio Ecuatoriano de Normalización (INEN): Quito, Ecuador, 1998.

- Chang, J.V.; Coronel, A.T.; Cortez, L.V.; Vasquez, K.A.; Flor, F.I. Extraction of Cocoa Powder for the Preparation of a Drink by Adding Mucilage and Guava. Sarhad J. Agric. 2024, 39, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Armenteros, T.M.; Guerra, L.S.; Ruales, J.; Ramos-Guerrero, L. Ecuadorian Cacao Mucilage as a Novel Culture Medium Ingredient: Unveiling Its Potential for Microbial Growth and Biotechnological Applications. Foods 2025, 14, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 3930:2000 (E)/OIML R 99:2000 (E); Instruments for measuring vehicle exhaust emissions. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000.

- Pacura, W.; Szramowiat-Sala, K.; Gołaś, J. Emissions from Light-Duty Vehicles—From Statistics to Emission Regulations and Vehicle Testing in the European Union. Energies 2023, 17, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroel-Bastidas, J.; Párraga-Maquilón, J.S.; Zapata-Zambrano, C.E.; Córdoba, M.d.G.; Rodríguez, A.; Hernández, A.; Briones-Bitar, J. Cacao Mucilage Valorisation to Produce Craft Beers: A Case Study Towards the Sustainability of the Cocoa Industry in Los Ríos Province. Beverages 2025, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulu, E.D.; Duraisamy, R.; Kebede, B.H.; Tura, A.M. Anchote (Coccinia abyssinica) starch extraction, characterization and bioethanol generation from its pulp/waste. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, A.A.; Ignat, R.M.; Bildea, C.S. Optimal extractive distillation process for bioethanol dehydration. In Computer Aided Chemical Engineering; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 33, pp. 1333–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janković, T.; Straathof, A.J.J.; McGregor, I.R.; Kiss, A.A. Bioethanol separation by a new pass-through distillation process. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 336, 126292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas-Grimaldo, C.; Avendaño-Guerrero, J.G.; Molina-Guerrero, C.E.; Segovia-Hernández, J.G. Design and control of a distillation sequence for the purification of bioethanol obtained from sotol bagasse (Dasylirium sp.). Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2024, 203, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlanga-Labari, C.; Albistur-Goñi, A.; Barado-Pardo, I.; Gutierrez-Peinado, M.; Fernández-Carrasquilla, J. Compatibility study of high density polyethylene with bioethanol–gasoline blends. Mater. Des. 2011, 32, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D323-15a; Standard Test Method for Vapor Pressure of Petroleum Products (Reid Method). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- ASTM D130-12; Standard Test Method for Corrosiveness to Copper from Petroleum Products by Copper Strip Test. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2012.

- Abdellatief, T.M.M.; Ershov, M.A.; Kapustin, V.M.; Chernysheva, E.A.; Mustafa, A. Low carbon energy technologies envisaged in the context of sustainable energy for producing high-octane gasoline fuel. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 56, 103103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.; Manigandan, S.; Mathimani, T.; Basha, S.; Xia, C.; Brindhadevi, K.; Unpaprom, Y.; Whangchai, K.; Pugazhendhi, A. An assessment of agricultural waste cellulosic biofuel for improved combustion and emission characteristics. Sci. Total Environ. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 813, 152418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schifter, I.; Diaz, L.; Rodriguez, R.; Gómez, J.P.; Gonzalez, U. Combustion and emissions behavior for ethanol–gasoline blends in a single cylinder engine. Fuel 2011, 90, 3586–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 228:2012; Automotive fuels—Unleaded petrol—Requirements and test methods. European Committee for Standardization: Brussel, Belgium, 2012.

- ASTM D5798; Standard Specification for Fuel Ethanol (E100) for Automotive Engines. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2011.

- Najafi, G.; Ghobadian, B.; Yusaf, T.; Ardebili, S.M.S.; Mamat, R. Optimization of performance and exhaust emission parameters of a SI (spark ignition) engine with gasoline–ethanol blended fuels using response surface methodology. Energy 2015, 90, 1815–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhang, S.-R.; Lin, Y.-C.; Chen, K.-S.; Lin, S.-L.; Batterman, S. Evaluation of fuel consumption, pollutant emissions and well-to-wheel GHGs assessment from a vehicle operation fueled with bioethanol, gasoline and hydrogen. Energy 2020, 209, 118436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, S.; Kiani, M.K.D.; Eslami, M.; Ghobadian, B. The effect of throttle valve positions on thermodynamic second law efficiency and availability of SI engine using bioethanol-gasoline blends. Renew. Energy 2017, 103, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufino, C.H.; de Lima, A.J.; Mattos, A.P.; Allah, F.U.; Bernal, J.L.; Ferreira, J.V.; Gallo, W.L. Exergetic analysis of a spark ignition engine fuelled with ethanol. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 192, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, B.; Lius, A.; Mahendar, S.K.; Mihaescu, M.; Cronhjort, A. Energy and exergy characteristics of an ethanol-fueled heavy-duty SI engine at high-load operation using lean-burn combustion. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 224, 120063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örs, İ.; Yelbey, S.; Gülcan, H.E.; Kul, B.S.; Ciniviz, M. Evaluation of detailed combustion, energy and exergy analysis on ethanol-gasoline and methanol-gasoline blends of a spark ignition engine. Fuel 2023, 354, 129340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasemian, A.; Haghparast, S.J.; Azarikhah, P.; Babaie, M. Effects of Compression Ratio of Bio-Fueled SI Engines on the Thermal Balance and Waste Heat Recovery Potential. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothare, C.B.; Kongre, S.; Malwe, P.; Sharma, K.; Qasem, N.A.; Ağbulut, Ü.; Eldin, S.M.; Panchal, H. Performance improvement and CO and HC emission reduction of variable compression ratio spark-ignition engine using n-pentanol as a fuel additive. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 74, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iodice, P.; Langella, G.; Amoresano, A. Ethanol in gasoline fuel blends: Effect on fuel consumption and engine out emissions of SI engines in cold operating conditions. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 130, 1081–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, A.T.; Nižetić, S.; Ölçer, A.I. 5-Dimethylfuran (DMF) as a promising biofuel for the spark ignition engine application: A comparative analysis and review. Fuel 2021, 285, 119140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, W.-D.; Chen, R.-H.; Wu, T.-L.; Lin, T.-H. Engine performance and pollutant emission of an SI engine using ethanol–gasoline blended fuels. Atmos. Environ. 2002, 36, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobin Siddique, M.B.; Khairuddin, N.; Ali, N.A.; Hassan, M.A.; Ahmed, J.; Kasem, S.; Tabassum, M.; Afrouzi, H.N. A comprehensive review on the application of bioethanol/biodiesel in direct injection engines and consequential environmental impact. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2021, 3, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Huang, Z.; Ren, L.; Tao, B.; Pan, J. Experimental Investigation of Combustion and Emission Characteristics of Ethanol–Gasoline Blends across Varying Operating Parameters. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 16079–16089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, T.; Mahendar, S.K.; Christiansen-Erlandsson, A.; Olofsson, U. The Effect of Pure Oxygenated Biofuels on Efficiency and Emissions in a Gasoline Optimised DISI Engine. Energies 2021, 14, 3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warguła, Ł.; Wieczorek, B.; Gierz, Ł.; Karwat, B. Critical Concerns Regarding the Transition from E5 to E10 Gasoline in the European Union, Particularly in Poland in 2024—A Theoretical and Experimental Analysis of the Problem of Controlling the Air–Fuel Mixture Composition (AFR) and the λ Coefficient. Energies 2025, 18, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshenawy, A.A.; Razik, S.M.A.; Gad, M.S. Modeling of combustion and emissions behavior on the effect of ethanol–gasoline blends in a four stroke SI engine. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2023, 15, 168781322311571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TEST | Standard/Method | E5–CCN51 Blend | Super | Extra | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower heating value | ASTM D4809-18 [29] | 45.218 | 47.124 | 45.882 | MJ/kg |

| Octane number (RON) | NTE INEN 2102 [37] | 85.8 | 92 | 85 | - |

| Distillation temperature (90%) | ASTM D86-15 [30] | 164 | 190 | 189 | °C |

| Distillation temperature (50%) | ASTM D86-15 [30] | 107 | 90 | 120 | °C |

| Distillation temperature (10%) | ASTM D86-15 [30] | 54.1 | 50 | 70 | °C |

| Reid vapor pressure | ASTM D323-15a [49] | 56.01 | 58 | 60 | kPa |

| Residue | ASTM D86-15 [30] | 1.01 | 1.1 | 2 | % |

| Gum content | ASTM D381 [35] | 3 | 4 | 3 | mg/100 mL |

| Sulfur content | ASTM D4294 [34] | 0.059 | 0.065 | 0.065 | % |

| Final boiling point | ASTM D86-15 [30] | 210 | 218 | 220 | °C |

| Copper strip corrosion | ASTM D130-12 [50] | 1a | 1a | 1a | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Laverde-Albarracín, C.; González González, J.F.; Ledesma Cano, B.; Román Suero, S.; Villarroel-Bastidas, J.; Peña-Banegas, D.; Puente-Bosquez, S.; Naranjo-Silva, S. Comparing Ecuadorian Cocoa Mucilage-Based Bio-Ethanol and Commercial Fuels Toward Their Performance and Environmental Impacts in Internal Combustion Engines. Energies 2025, 18, 6378. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246378

Laverde-Albarracín C, González González JF, Ledesma Cano B, Román Suero S, Villarroel-Bastidas J, Peña-Banegas D, Puente-Bosquez S, Naranjo-Silva S. Comparing Ecuadorian Cocoa Mucilage-Based Bio-Ethanol and Commercial Fuels Toward Their Performance and Environmental Impacts in Internal Combustion Engines. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6378. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246378

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaverde-Albarracín, Cristian, Juan Félix González González, Beatriz Ledesma Cano, Silvia Román Suero, José Villarroel-Bastidas, Diego Peña-Banegas, Samantha Puente-Bosquez, and Sebastian Naranjo-Silva. 2025. "Comparing Ecuadorian Cocoa Mucilage-Based Bio-Ethanol and Commercial Fuels Toward Their Performance and Environmental Impacts in Internal Combustion Engines" Energies 18, no. 24: 6378. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246378

APA StyleLaverde-Albarracín, C., González González, J. F., Ledesma Cano, B., Román Suero, S., Villarroel-Bastidas, J., Peña-Banegas, D., Puente-Bosquez, S., & Naranjo-Silva, S. (2025). Comparing Ecuadorian Cocoa Mucilage-Based Bio-Ethanol and Commercial Fuels Toward Their Performance and Environmental Impacts in Internal Combustion Engines. Energies, 18(24), 6378. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246378