Trend Prediction of Valve Internal Leakage in Thermal Power Plants Based on Improved ARIMA-GARCH

Abstract

1. Introduction

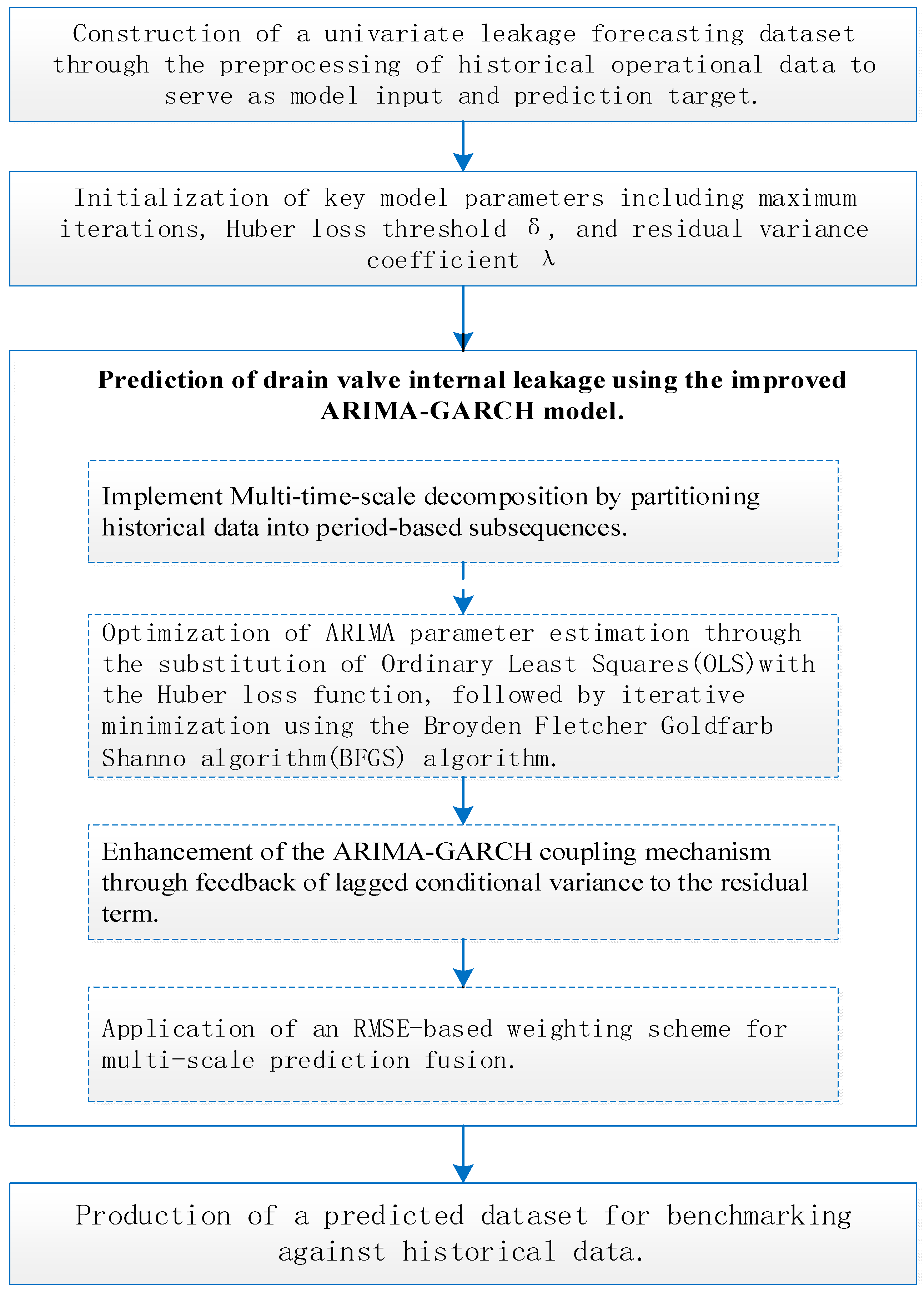

2. The Overall Idea of the IARIMA-GARCH Prediction Model

- (1)

- Collect historical operational data of univariate valve internal leakage, which consists of time-sequenced measurements of internal valve leakage. Preprocess the historical internal leakage data, and construct the drain valve internal leakage prediction dataset.

- (2)

- Before inputting the dataset into the prediction model, initialize model parameters, including the maximum number of iterations, the Huber loss threshold δ, and the conditional variance coefficient λ in the residual term.

- (3)

- Utilize the IARIMA-GARCH method to achieve valve internal leakage prediction for thermal power plants.

- (1)

- Decompose the valve internal leakage time series into short-term, medium-term, and long-term subsequences according to different prediction periods using the Multi-Time-Scale Decomposition method to capture evolutionary characteristics at different time scales.

- (2)

- Use the Huber loss function instead of the OLS function to construct the IARIMA model as the internal leakage prediction model, optimizing the key parameters of the ARIMA model to effectively suppress the interference of outliers.

- (3)

- By introducing the previous moment’s volatility to correct the current residual, construct the Improved GARCH (IGARCH) model as the internal leakage volatility prediction model, establishing a feedback mechanism between the mean and volatility equations to enhance the characterization of volatility clustering.

- (4)

- Dynamically calculate weights based on the prediction errors of each subsequence, and fuse the multi-scale prediction results to obtain the optimized internal leakage prediction value.

- (4)

- Obtain the final internal leakage prediction value and conduct a comparative study with the test dataset to evaluate prediction accuracy and error analysis.

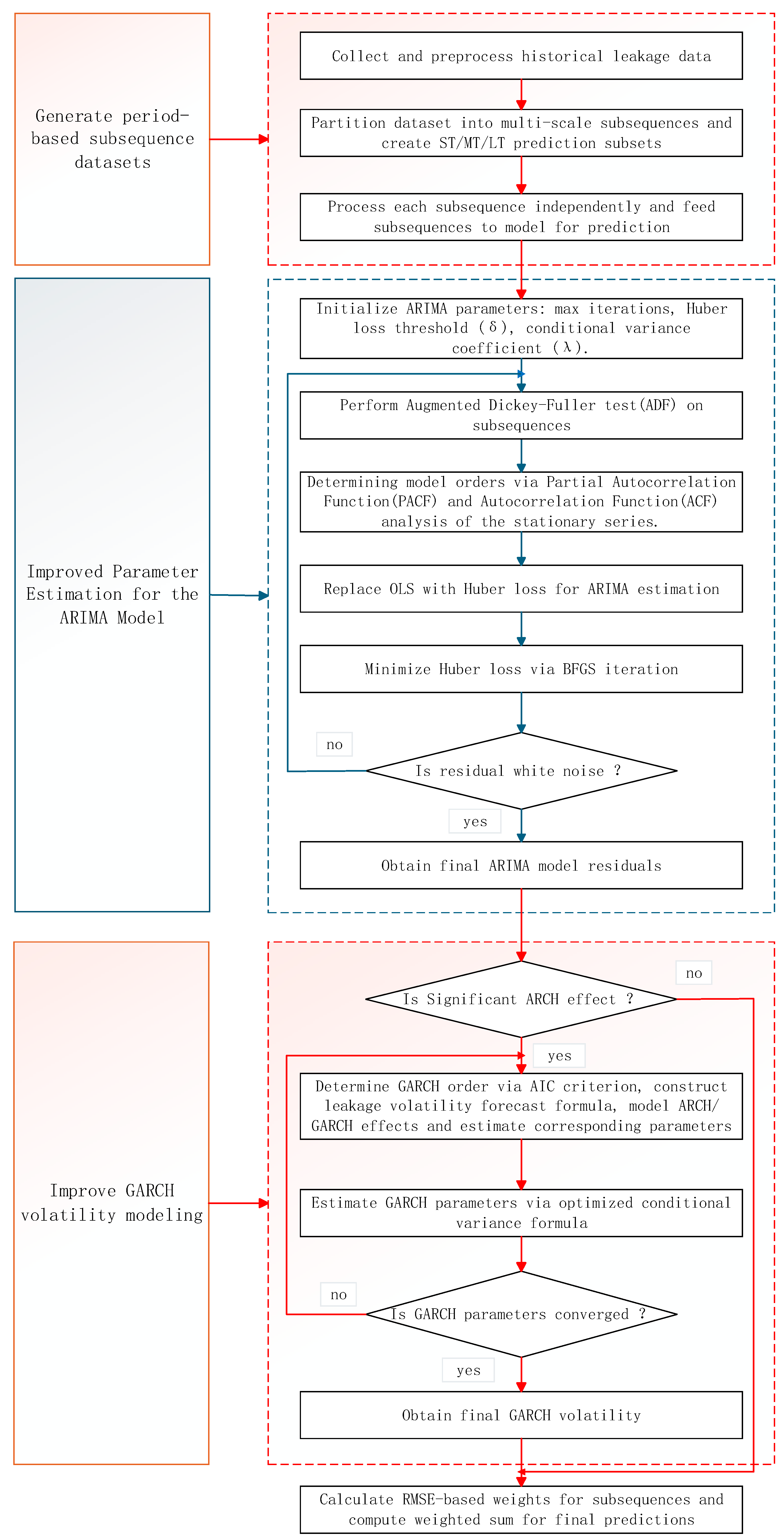

3. Implementation of IARIMA-GARCH Method

3.1. Construction of the Multi-Time-Scale Prediction Framework

- (1)

- Based on the internal leakage prediction dataset , directly truncate a segment of length TD from the internal leakage data to form the short-term subsequence dataset , expressed as:where TD is the subsequence length

- (2)

- Based on the internal leakage prediction dataset take the average of every internal leakage values to obtain , forming the medium-term scale subsequence dataset , as follows:where TZ is the subsequence length.

- (2)

- Based on the internal leakage prediction dataset , take the average of every internal leakage values (where ) to obtain , forming the long-term scale subsequence dataset , as follows:where TC is the subsequence length.

3.2. Improved ARIMA Model

- (1)

- Initialize the ARIMA model parameters, including the maximum number of iterations, the Huber loss threshold δ, and the conditional variance coefficient λ in the residual term, among others.

- (2)

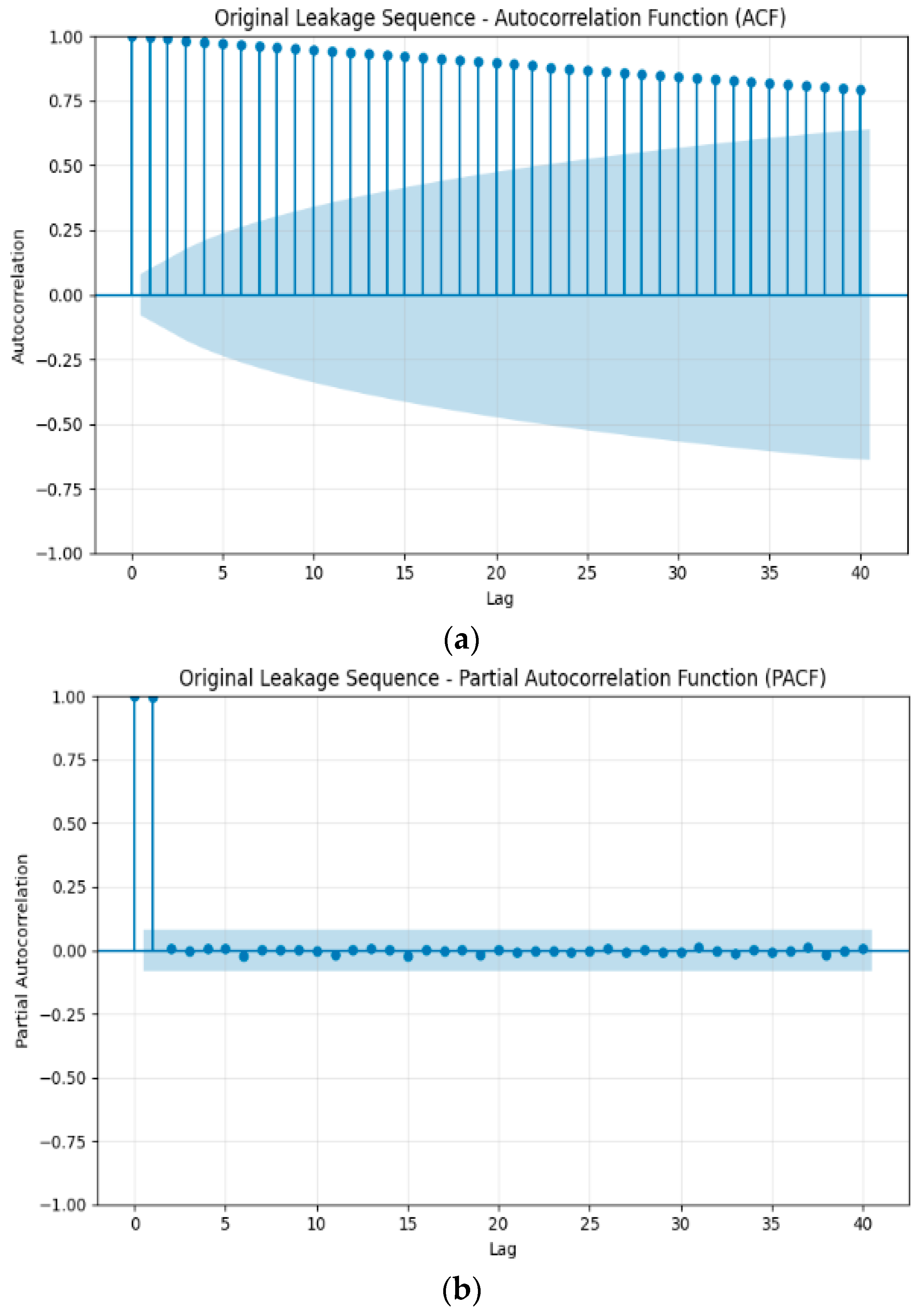

- Data Stationarity Processing and Model Order Determination.

- (3)

- Improved ARIMA Model Parameter Estimation

- (4)

- Obtain the predicted value from the ARIMA model, and then derive the corresponding internal leakage prediction value .

3.3. Improved GARCH Model

- (1)

- GARCH Effect Test

- (2)

- GARCH Model Order Determination

- (3)

- Improved Residual Term Calculation

3.4. Multi-Time-Scale Prediction Result Fusion

4. Case Analysis Setup

4.1. Data Source and Characteristic Analysis

- (1)

- Data Source

- (2)

- Data Characteristic Analysis

4.2. Model Construction

- (1)

- Model Parameter Selection Strategy

- (2)

- Model construction details

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

4.4. Experimental Platform

5. Results and Discussion

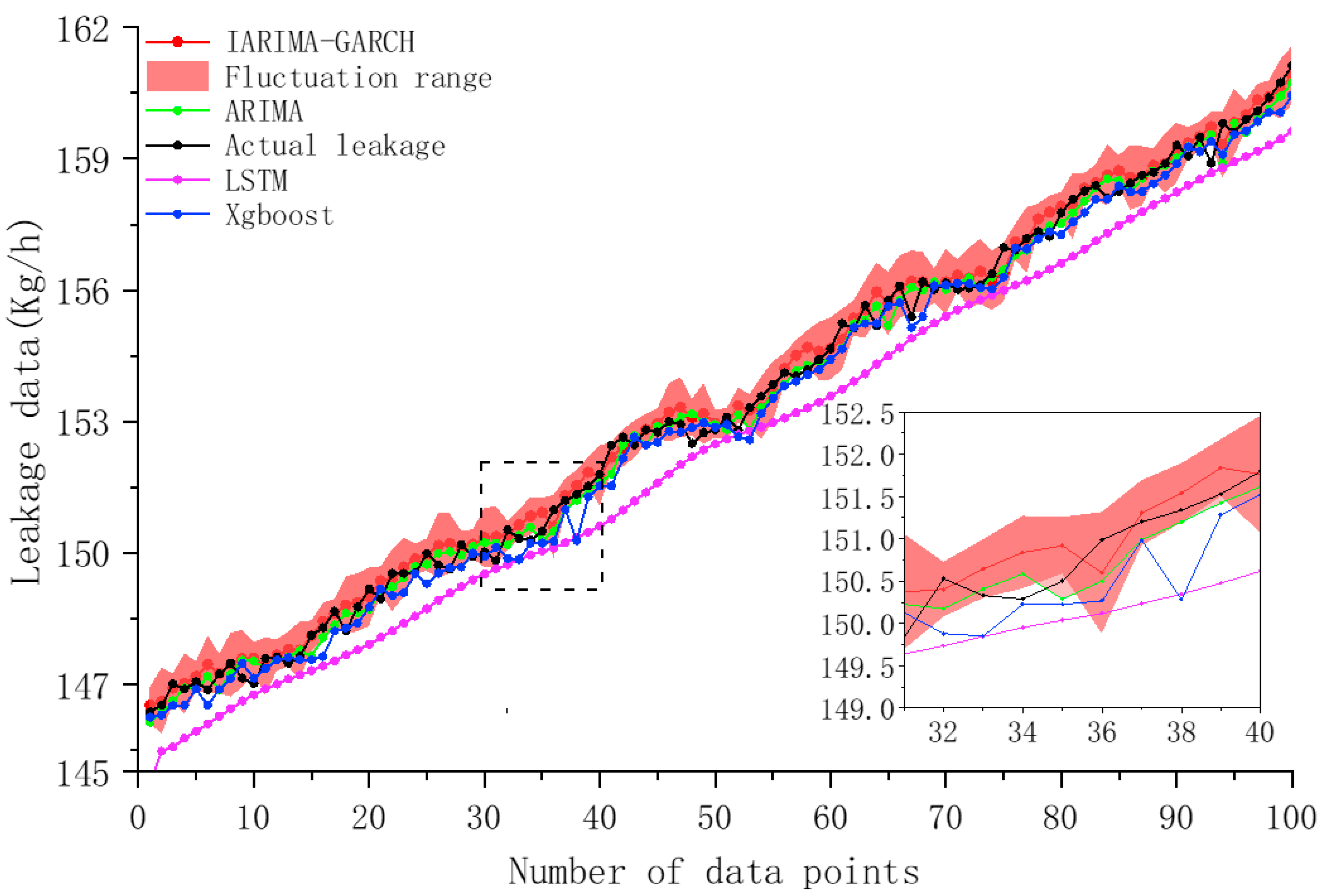

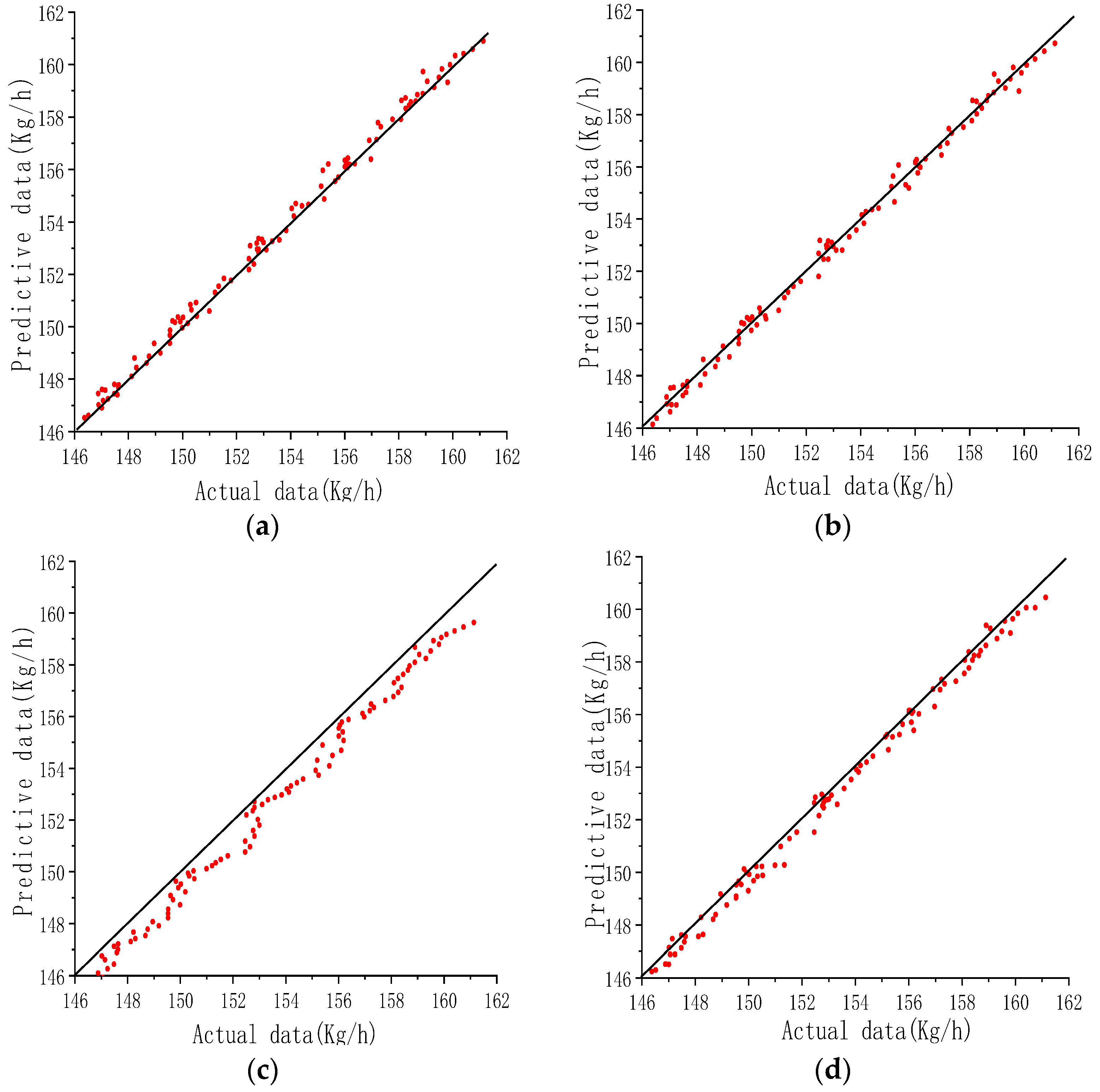

5.1. In-Distribution (ID) Test

- (1)

- Adopt a parallelized training strategy. Since the model for each valve is independent and the training tasks do not depend on each other, they are highly suitable for embarrassingly parallel processing on computing clusters or cloud platforms. This approach can linearly reduce the overall training time.

- (2)

- Implement an edge-cloud collaborative architecture. Deploying the trained models at the edge for real-time prediction can significantly reduce the bandwidth and computational pressure on the central system. Model retraining or updates can be performed periodically in the cloud.

- (3)

- Introduce incremental learning mechanisms. Future work could explore the model’s online learning capability. When new operational data becomes available, instead of performing full retraining, the model parameters could be fine-tuned through incremental update strategies, thereby substantially reducing the computational costs of long-term maintenance.

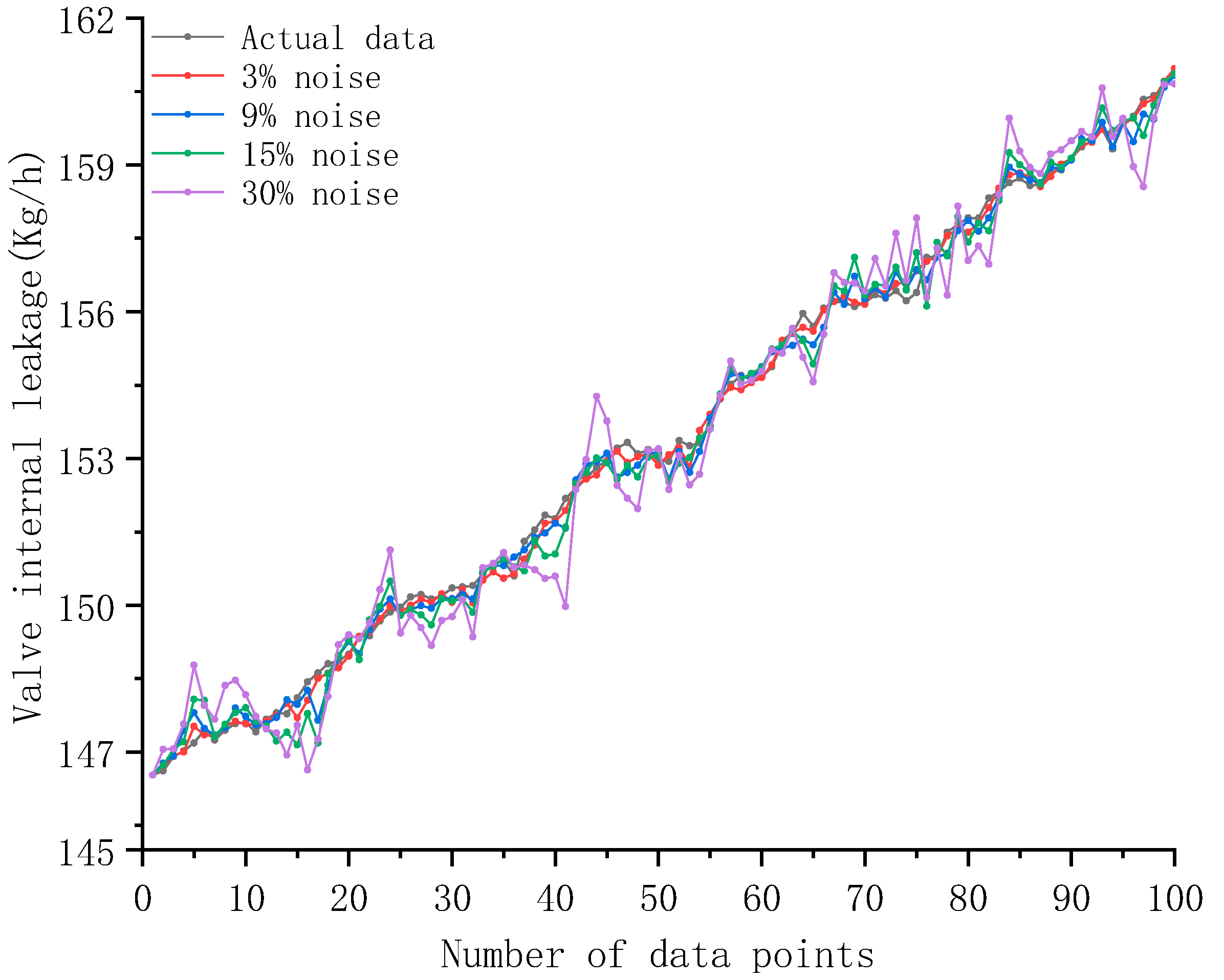

5.2. OOD Test Based on Noise Injection

6. Conclusions

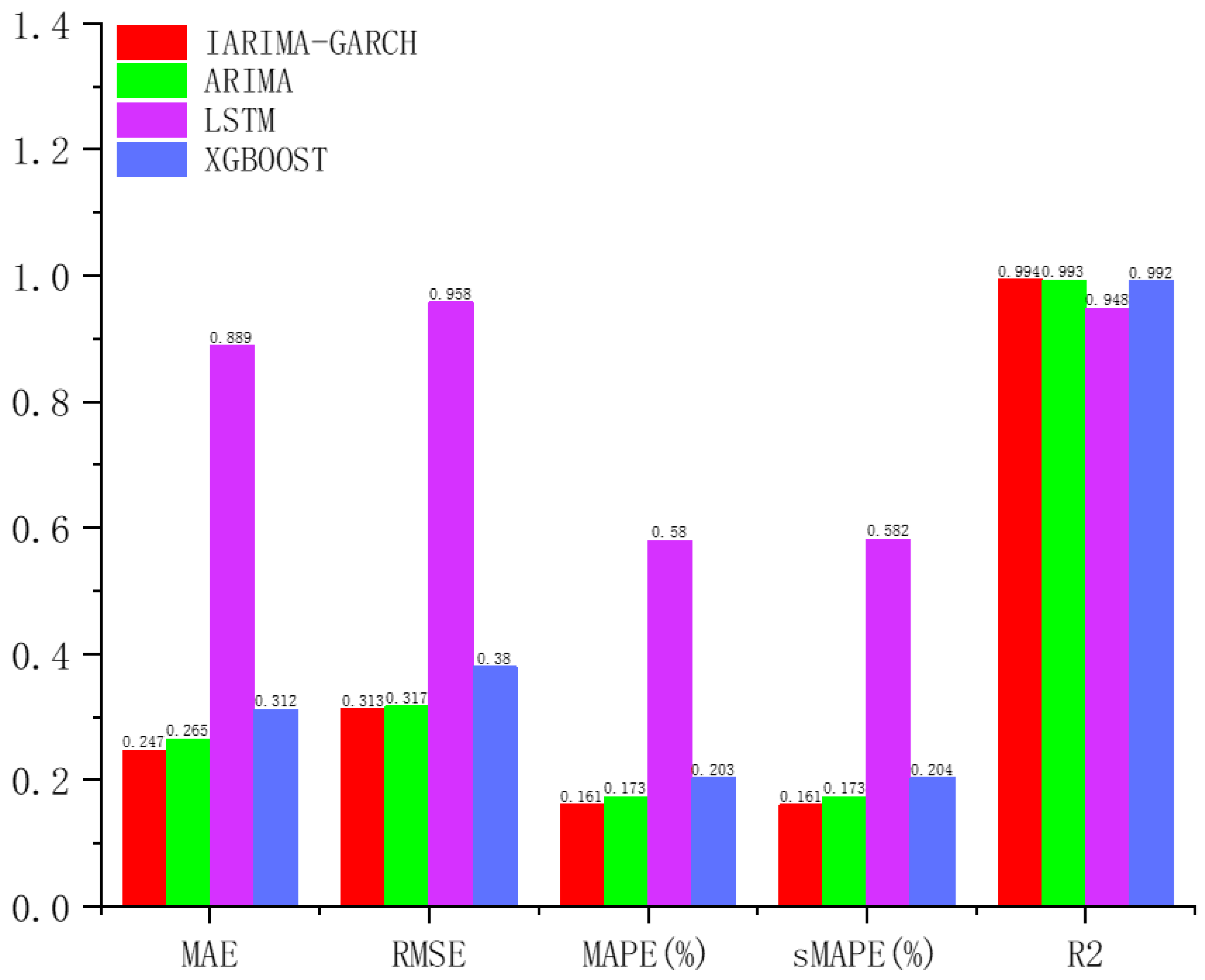

- (1)

- Compared to ARIMA, LSTM, and XGBoost, IARIMA-GARCH has the highest prediction accuracy and is significantly better than the other methods. Its prediction curve has the highest degree of agreement with the actual leakage curve. Its MAE is 0.247, RMSE is 0.313, MAPE is 0.161, and sMAPE is 0.161, which are the smallest among the four methods and significantly lower than the other methods; its R2 is 0.994, very close to 1, and is the highest among the four.

- (2)

- IARIMA-GARCH can effectively quantify prediction uncertainty and provide reliable prediction intervals. The prediction interval (volatility interval) it outputs can effectively encompass most of the actual leakage data points. This not only proves that the GARCH component successfully captures the volatility clustering of the series but also provides an intuitive and reliable quantitative basis for risk assessment in engineering practice.

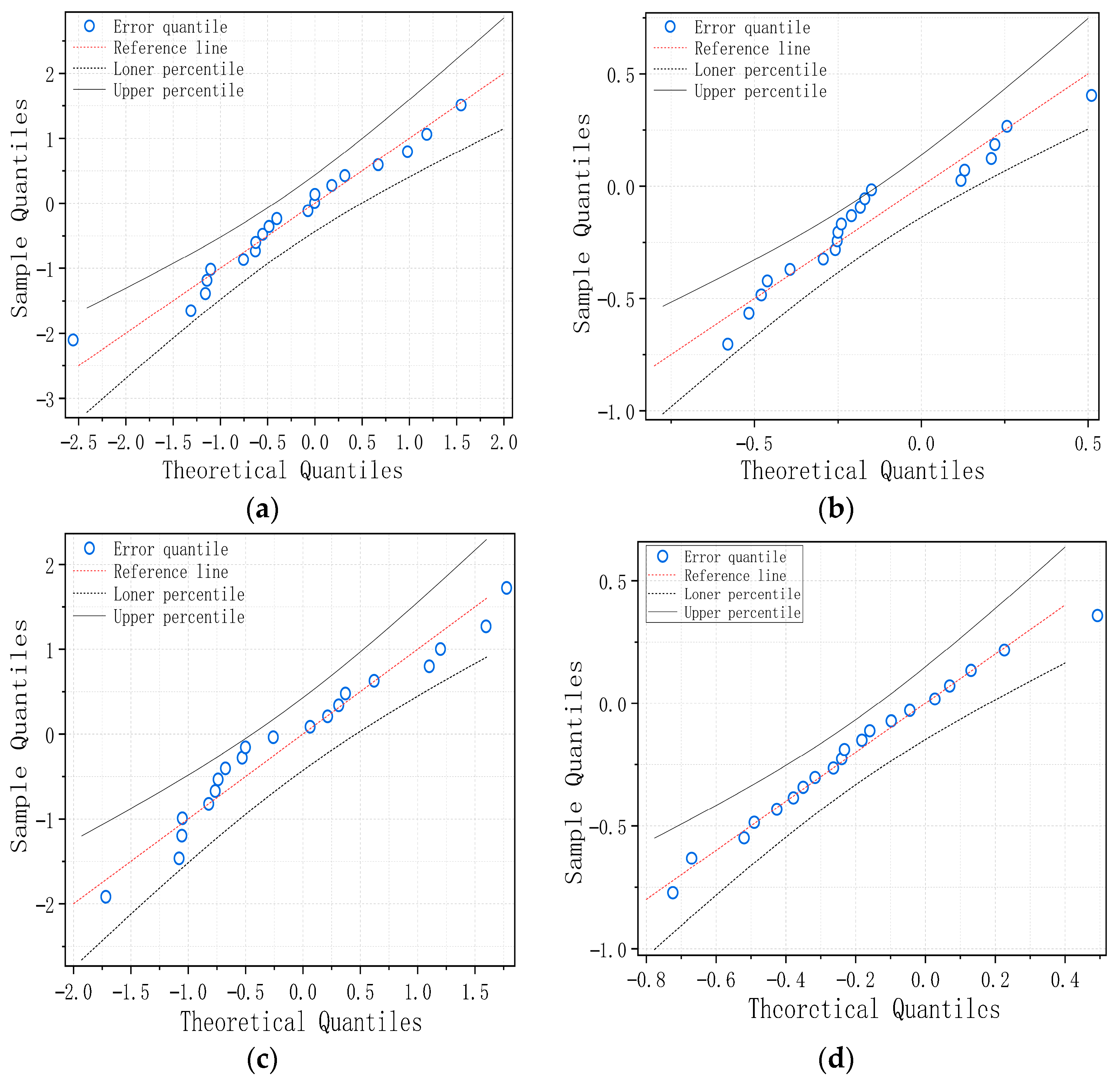

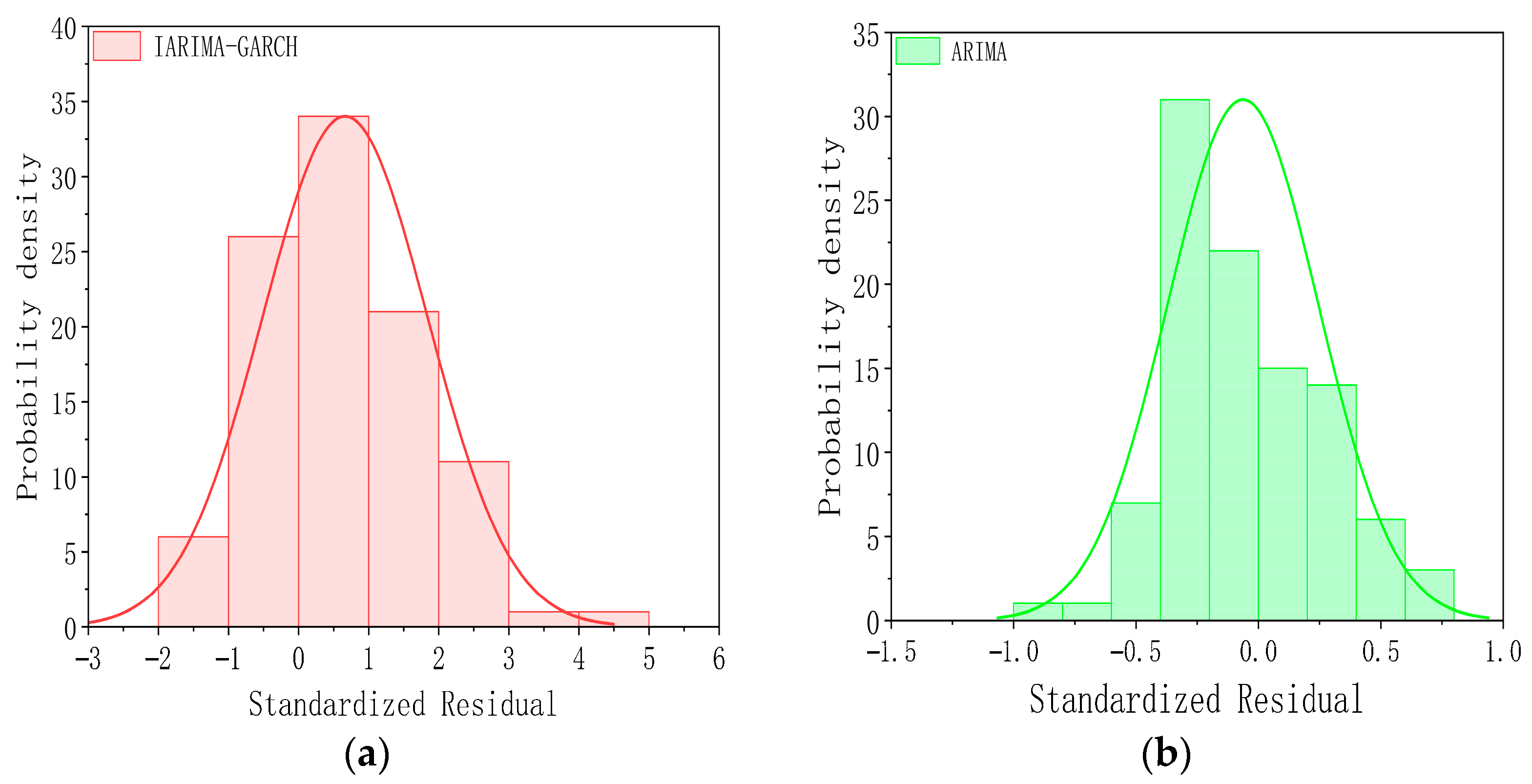

- (3)

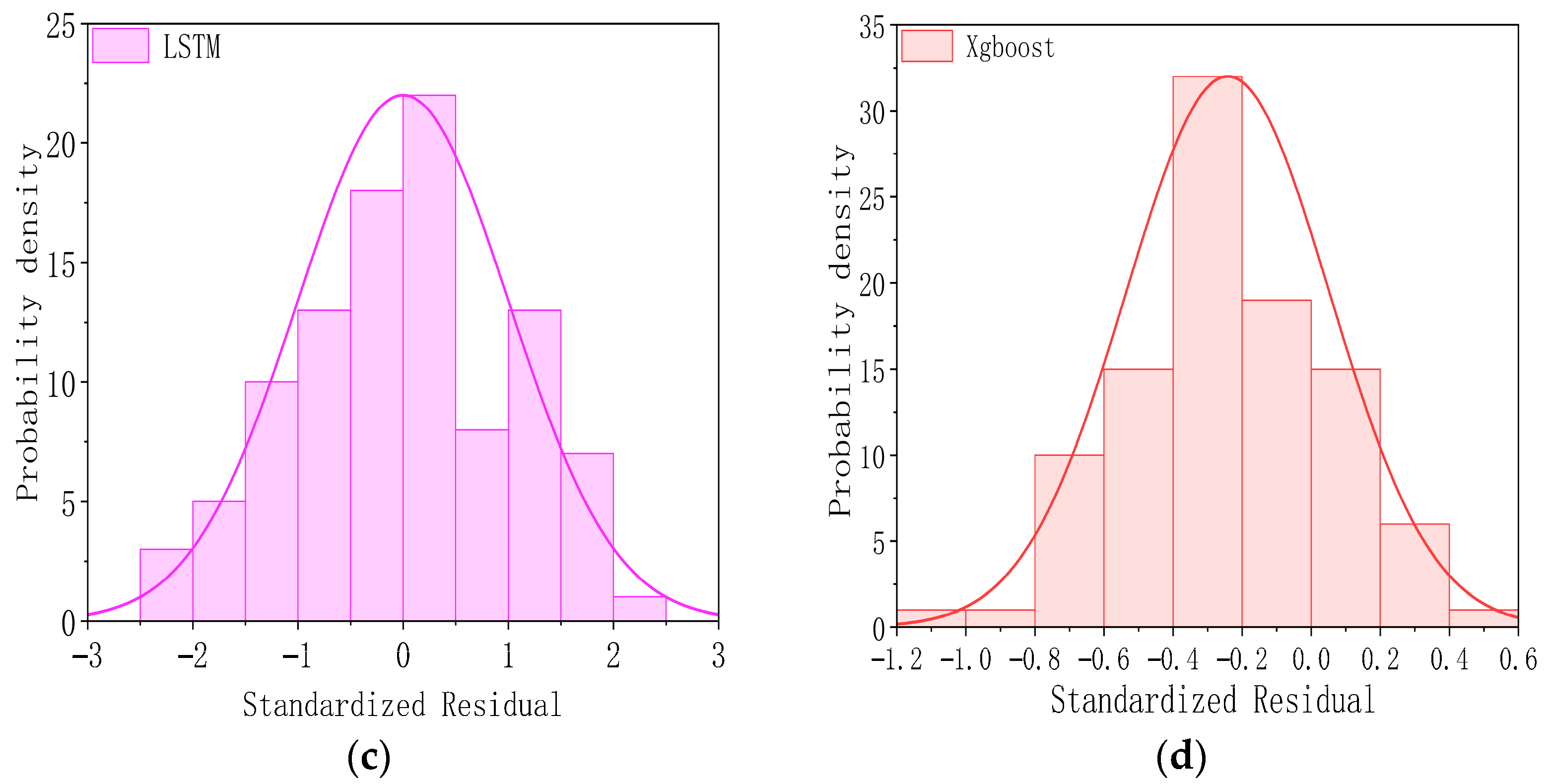

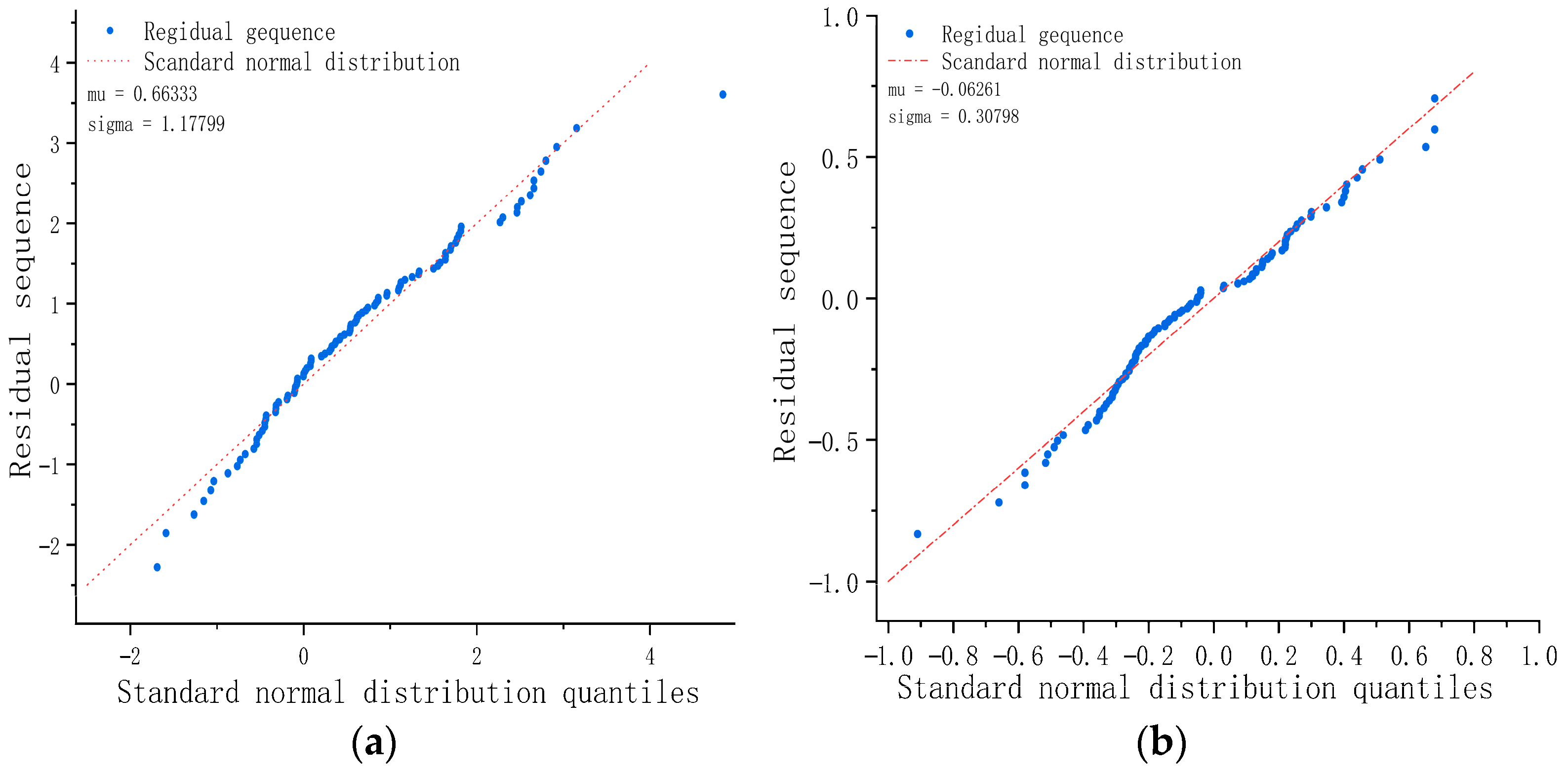

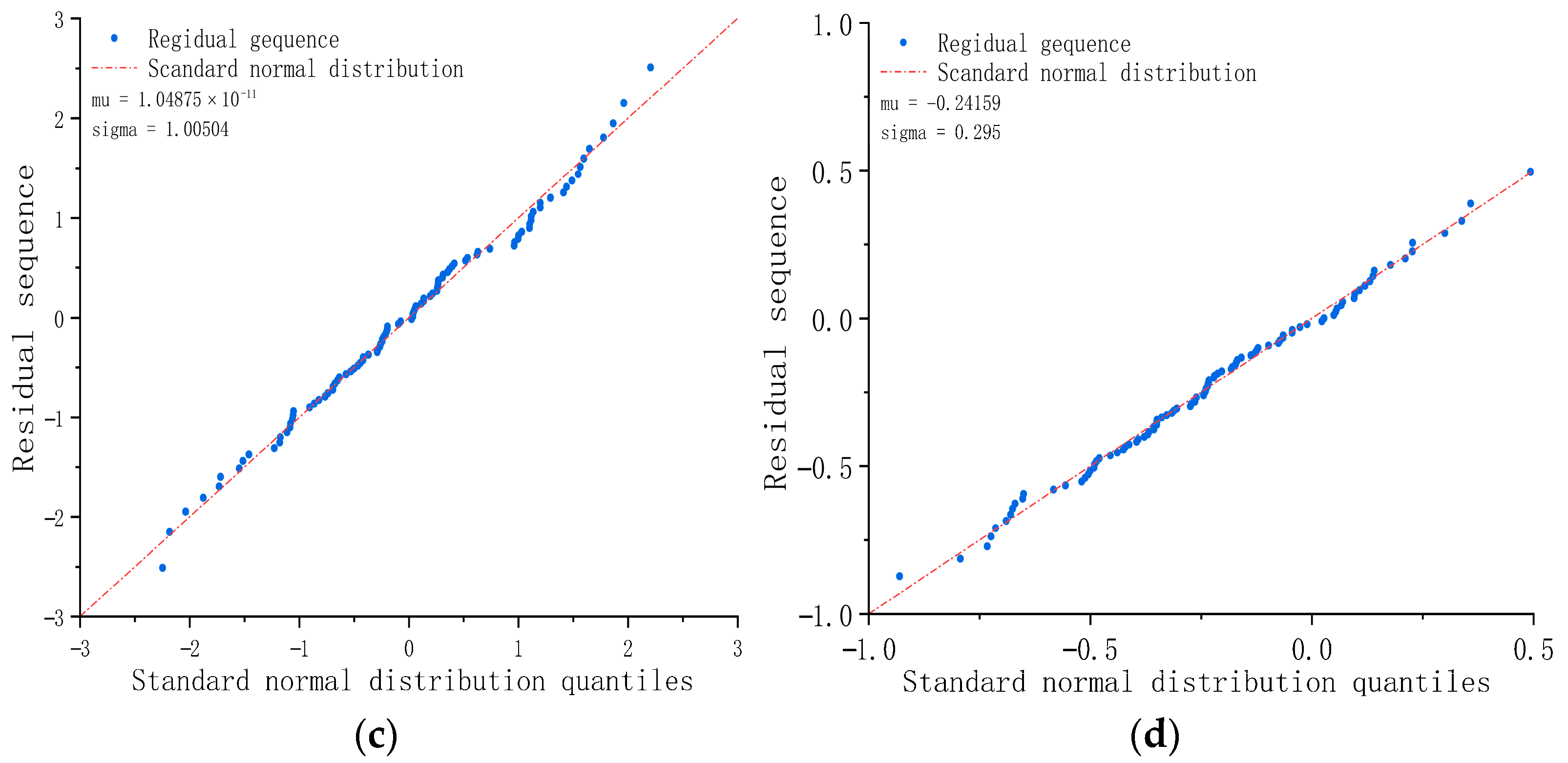

- The residuals of IARIMA-GARCH satisfy the statistical assumptions, verifying the completeness of the model specification. From the diagnostic results of the normal distribution plot and Q-Q plot, the standardized residual sequence of IARIMA-GARCH is closest to a white noise sequence with zero mean and unit variance, and its distribution shape is closer to a normal distribution than the other methods. This indicates that it has fully extracted the linear and nonlinear patterns in the series, and there is no significant predictable information left in the residuals, statistically proving the rationality and superiority of the model specification.

- (1)

- Validation on multiple valve types. The method will be extended to different types of valves such as reheat steam drain valves and extraction steam drain valves at various stages, testing its predictive performance under diverse working conditions including high-pressure/high-temperature, medium-pressure/medium-temperature, and low-pressure/low-temperature environments.

- (2)

- Testing on units of different capacity classes. The method will be deployed on thermal power units with different capacities (300 MW, 600 MW, 1000 MW) to evaluate its robustness under varying load fluctuations, operational strategies, and equipment aging levels.

- (3)

- Adaptation to multiple operational conditions. The method’s adaptability under complex operational scenarios such as variable load operation, frequent start–stop cycles, and extreme conditions will be explored. By developing online learning mechanisms to accommodate performance shifts due to equipment aging, and by investigating transfer learning-based methods for rapid cross-domain model adaptation, the method’s generalization ability across different unit capacities and valve types will be enhanced to ensure its reliability across the full range of operating conditions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| ARIMA | Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average Model |

| IARIMA | Improved Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average Model |

| GARCH | Generalized AutoRegressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity |

| IGARCH | Improved Generalized AutoRegressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Networks |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| XGBoost | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

| MPPT | Maximum Power Point Tracking |

| SSA | Salp Swarm Algorithm |

| P&O | Perturb and Observe |

| ACF | Autocorrelation Function |

| PACF | Partial Autocorrelation Function |

| ADF | Augmented Dickey–Fuller |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| RMSE | Root-Mean-Squared Error |

| R2 | Determination Coefficient |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| sMAPE | Symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| Parameter | Meaning |

| Number of internal leaks | |

| the stationary series in the ARIMA model | |

| dth-order difference operator | |

| Lag operator | |

| Subsequence set | |

| Autocorrelation function value | |

| Autocovariance function | |

| Time series variance | |

| Time series mean | |

| Error term | |

| Lagged Observation | |

| Regression coefficient | |

| Predicted value of a stationary time series at time t | |

| Model constant term | |

| Autoregressive coefficients of the AR part | |

| Moving average coefficient of the MA part | |

| Lag term of a stationary series | |

| Previous period residual term | |

| Residual at time t | |

| Huber loss function threshold | |

| The derivative of the Huber loss function | |

| Step k inverse Hessian approximation | |

| Parameter Increment | |

| Gradient Increment | |

| Convergence tolerance | |

| Maximum number of iterations | |

| Assist in regressing the constant term | |

| Auxiliary regression coefficient | |

| Auxiliary regression error term | |

| T | Auxiliary regression sample size |

| Coefficient of determination for auxiliary regression | |

| Conditional variance at time t | |

| Constant term (intercept) | |

| Coefficient of the ARCH term | |

| Coefficient of the GARCH term | |

| The sun position before mutation | |

| N | Total number of observations |

| Conditional coefficient of variation | |

| Error metric based on RMSE | |

| Number of samples contained in the subsequence | |

| A positive number arbitrarily smaller than the normal error |

References

- Zheng, D.J.; Wang, X.; Yang, L.L.; Li, Y.Q.; Xia, H.; Zhang, H.C.; Xiang, X.M. Review of Acoustic Emission Detection Technology for Valve Internal Leakage: Mechanisms, Methods, Challenges, and Application Prospects. J. Sens. Technol. 2025, 25, 4487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, T.; Guo, R.Z.; Jia, F.S.; Yuan, X.H.; Guo, Z.H.; He, C.B. Quantitative analysis and influencing factors research on valve internal leakage in thermal power unit. In Proceedings of the 7th Asia Energy and Electrical Engineering Symposium, Chengdu, China, 28 March 2025; pp. 748–753. [Google Scholar]

- Elatar, A. Advancements in Heat Transfer and Fluid Mechanics (Fundamentals and Applications). J. Energy Res. 2025, 18, 3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, R.; Ryuzono, K.; Date, S.; Abe, Y.; Okabe, T. Structural optimization of composite aircraft wing considering fluid–structure interaction and damage tolerance assessment using continuum damage mechanics. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2025, 167, 110652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, M.S.; Munir, M.F.; Waseem, A. AI for Cleaner Air: Predictive Modeling of PM2.5 Using Deep Learning and Traditional Time-Series Approaches. J. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2025, 144, 3557–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Cuevas, P.; Diaz-del-Rio, F.; Casanueva-Morato, D.; Rios-Navarro, A. Competitive cost-effective memory access predictor through short-term online SVM and dynamic vocabularies. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2025, 164, 107592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddouchi, M.; Berrado, A. Forest-ORE: Mining an optimal rule ensemble to interpret random forest models. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 143, 109997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, C.; Bai, F. PROPHET: PRediction of 5G bandwidth using Event-driven causal Transformer. Proc. ACM Meas. Anal. Comput. Syst. 2025, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Ahn, Y. Comparative Study of RNN-Based Deep Learning Models for Practical 6-DOF Ship Motion Prediction. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Liang, R.; Yuan, B.; Hu, J. DIMO-CNN: Deep Learning Toolkit-Accelerated Analytical Modeling and Optimization of CNN Hardware and Dataflow. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2025, 44, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, K.; Wu, Y.; Ye, X.; Yang, H.; Li, X. ProxyMatting: Transformer-based image matting via region proxy. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 310, 112911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisen, V.A.; Lévy-Leduc, C.; Solci, C.C. A robust M-estimator for Gaussian ARMA time series based on the Whittle approximation. J. Appl. Math. Model. 2025, 137, 115712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolakopoulos, E. Bayesian Semiparametric Multivariate Realized GARCH Modeling. J. Forecast. 2025, 44, 2106–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Jiang, G.; Jiang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Y. A single-sensor leak localization method for high-temperature and high-pressure steam superheater pipes based on VMD-ARMA-SSMUSIC. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 280, 128210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiangxin, X.; Isah, K.O.; Yakub, Y.; Aboluwodi, D. Revisiting the Volatility Dynamics of REITs Amid Uncertainty and Investor Sentiment: A Predictive Approach in GARCH-MIDAS. J. Forecast. 2025, 44, 2193–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Tian, X. Research on Leak Detection of Low-Pressure Gas Pipelines in Buildings Based on Improved Variational Mode Decomposition and Robust Kalman Filtering. J. Sens. Technol. 2024, 24, 4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhu, T.; Jiang, Z. A method of milling force predictions for machining tools based on an improved ARMA model. J. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 2023, 95, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syuhada, K.; Tjahjono, V.; Hakim, A. Improving Value-at-Risk forecast using GA-ARMA-GARCH and AI-KDE models. J. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 148, 110885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.C.; Chen, W.N.; Guo, X.Q.; Zhong, J.H.; Wang, D.J. DRIFT: A Dynamic Crowd Inflow Control System Using LSTM-Based Deep Reinforcement Learning. J. Syst. Man Cybern. 2025, 55, 4202–4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Liu, M.Z.; Tang, M.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, J.W. XGBoost-Based Power Grid Fault Prediction with Feature Enhancement: Application to Meteorology. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2025, 82, 2893–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Meng, C.; Li, L.; Wu, H.; Wang, Y.; He, J.; Huang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Alassafi, M.O.; Alsaadi, F.E.; et al. Fault detection of wind turbine pitch connection bolts based on TSDAS-SMOTE with XGBOOST. Fractals 2023, 31, 2340147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. Extended Multivariate EGARCH Model: A Model for Zero-Return and Negative Spillovers. J. Forecast. 2025, 44, 1266–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.Y.; Song, K.; Jiang, S.L.; Zhao, Z.Q.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Li, C.; Sun, J.W. A Robust Salp Swarm Algorithm for Photovoltaic Maximum Power Point Tracking Under Partial Shading Conditions. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharatheedasan, K.; Maity, T.; Kumaraswamidhas, L.A. Enhanced fault diagnosis and remaining useful life prediction of rolling bearings using a hybrid multilayer perceptron and LSTM network model. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 115, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.H.; Lou, X.P. Rolling Bearing Fault Diagnosis Method Based on SWT and Improved Vision Transformer. Sensors 2025, 25, 2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Model | p | q | Huber Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| ARIMA(1, 1, 0) | 1 | 0 | 0.04062 |

| ARIMA(1, 1, 1) | 1 | 1 | 0.03991 |

| ARIMA(1, 1, 2) | 1 | 2 | 0.04000 |

| ARIMA(1, 1, 3) | 1 | 3 | 0.03661 |

| ARIMA(2, 1, 0) | 2 | 0 | 0.04011 |

| ARIMA(2, 1, 1) | 2 | 1 | 0.04004 |

| ARIMA(2, 1, 2) | 2 | 2 | 0.03998 |

| ARIMA(2, 1, 3) | 2 | 3 | 0.06410 |

| Model | m | n | Number of Parameters | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GARCH(1, 1) | 1 | 1 | 9 | 1437.5 |

| GARCH(1, 2) | 1 | 2 | 10 | 1439.9 |

| GARCH(2, 1) | 2 | 1 | 10 | 1439.6 |

| GARCH(2, 2) | 2 | 2 | 11 | 1437.9 |

| MAE | RMSE | MAPE | sMAPE | R2 | Time (s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IARIMA-GARCH | 0.247 | 0.313 | 0.161 | 0.161 | 0.994 | 674 |

| ARIMA | 0.265 | 0.317 | 0.173 | 0.173 | 0.993 | 62 |

| LSTM | 0.889 | 0.958 | 0.580 | 0.582 | 0.948 | 1743 |

| XGBoost | 0.312 | 0.380 | 0.203 | 0.204 | 0.992 | 324 |

| White Noise Ratio | R2 | MAE | RMSE | MAPE | sMAPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% | 0.9943 | 0.2465 | 0.3134 | 0.1610 | 0.1608 |

| 3% | 0.9937 | 0.2537 | 0.3279 | 0.1657 | 0.1656 |

| 6% | 0.9901 | 0.3467 | 0.4261 | 0.2265 | 0.2263 |

| 9% | 0.9834 | 0.4529 | 0.5534 | 0.2958 | 0.2955 |

| 12% | 0.9758 | 0.5344 | 0.6580 | 0.3488 | 0.3485 |

| 15% | 0.9650 | 0.6509 | 0.7945 | 0.4250 | 0.4247 |

| 18% | 0.9557 | 0.7263 | 0.9027 | 0.4740 | 0.4736 |

| 21% | 0.9433 | 0.8255 | 1.0315 | 0.5392 | 0.5386 |

| 24% | 0.9312 | 0.9118 | 1.1435 | 0.5949 | 0.5944 |

| 27% | 0.9064 | 1.0855 | 1.3471 | 0.7099 | 0.7092 |

| 30% | 0.8928 | 1.1578 | 1.4429 | 0.7567 | 0.7557 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hou, R.; Cong, L.; Li, K.; Guo, Z.; Yuan, X.; He, C. Trend Prediction of Valve Internal Leakage in Thermal Power Plants Based on Improved ARIMA-GARCH. Energies 2025, 18, 6275. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236275

Hou R, Cong L, Li K, Guo Z, Yuan X, He C. Trend Prediction of Valve Internal Leakage in Thermal Power Plants Based on Improved ARIMA-GARCH. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6275. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236275

Chicago/Turabian StyleHou, Ruichun, Lin Cong, Kaiyong Li, Zihao Guo, Xinghua Yuan, and Chengbing He. 2025. "Trend Prediction of Valve Internal Leakage in Thermal Power Plants Based on Improved ARIMA-GARCH" Energies 18, no. 23: 6275. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236275

APA StyleHou, R., Cong, L., Li, K., Guo, Z., Yuan, X., & He, C. (2025). Trend Prediction of Valve Internal Leakage in Thermal Power Plants Based on Improved ARIMA-GARCH. Energies, 18(23), 6275. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236275