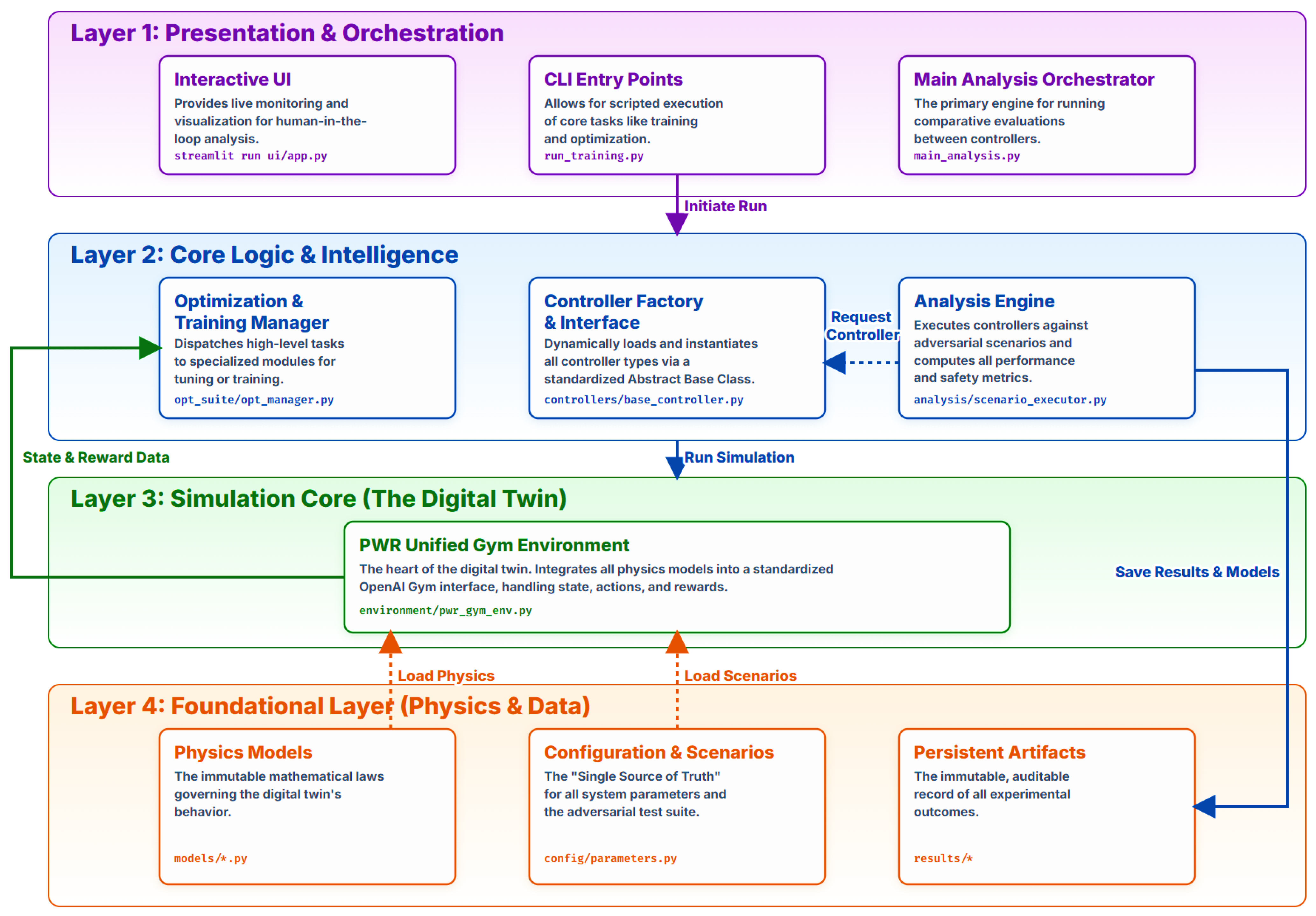

Figure 1.

System architecture.

Figure 1.

System architecture.

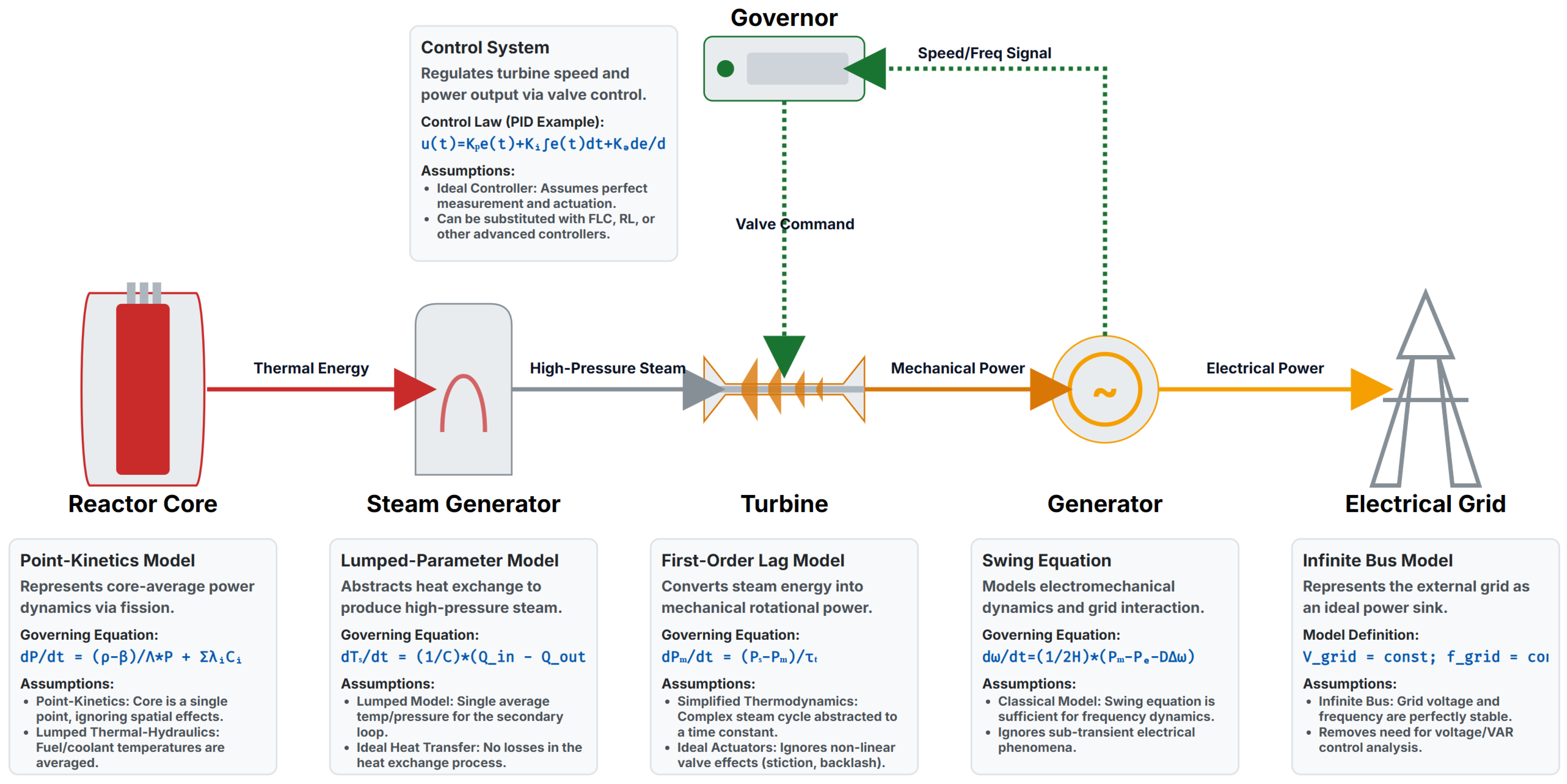

Figure 2.

System block diagram.

Figure 2.

System block diagram.

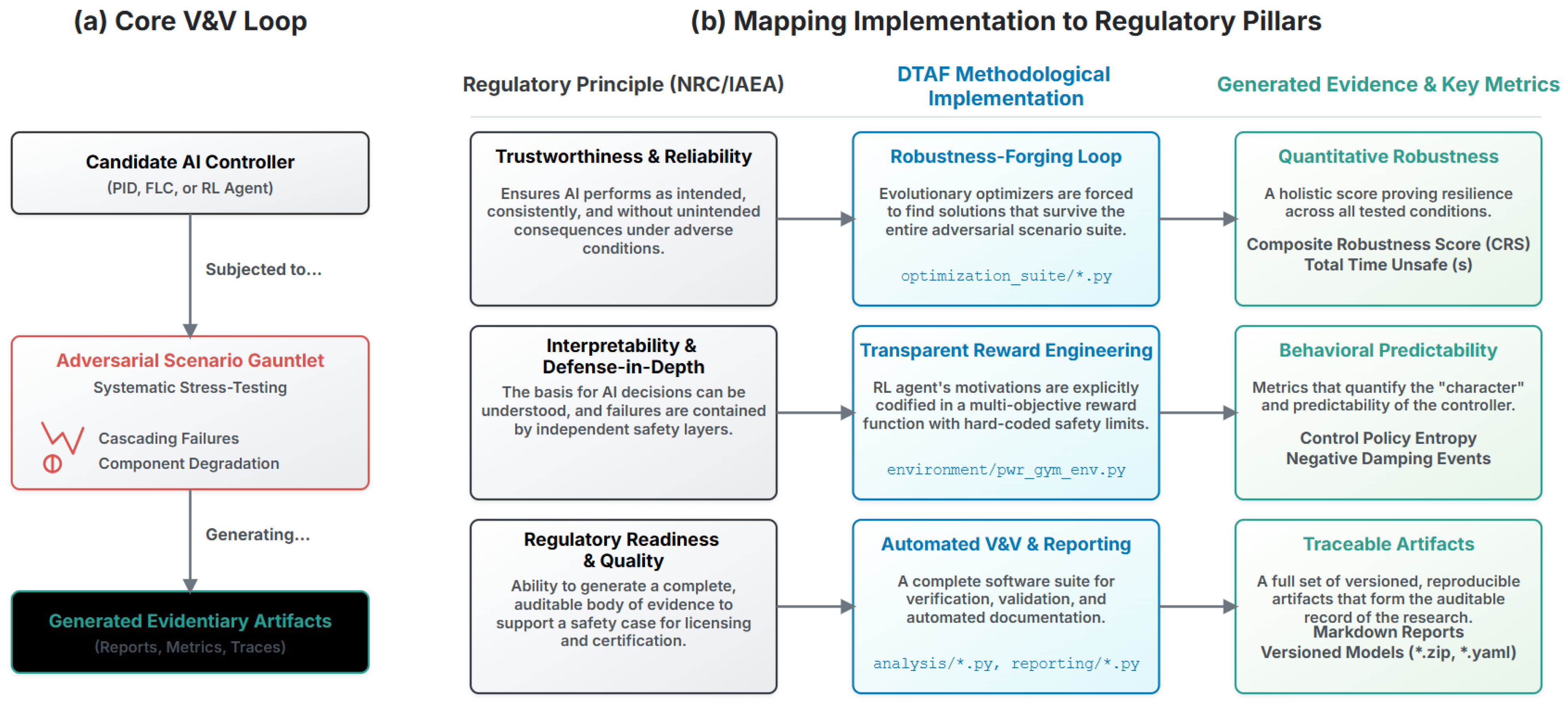

Figure 3.

Digital Twin Assurance Framework (DTAF): Deterministic orchestration that binds stress scenarios, quantitative gates, and auditable artifacts into a regulator-ready licensing pipeline. The four pillars—Trustworthiness and Reliability, Interpretability and Defense-in-Depth, Regulatory Readiness and Quality, and Continual Assurance—anchor the evidence channels and pass/fail logic.

Figure 3.

Digital Twin Assurance Framework (DTAF): Deterministic orchestration that binds stress scenarios, quantitative gates, and auditable artifacts into a regulator-ready licensing pipeline. The four pillars—Trustworthiness and Reliability, Interpretability and Defense-in-Depth, Regulatory Readiness and Quality, and Continual Assurance—anchor the evidence channels and pass/fail logic.

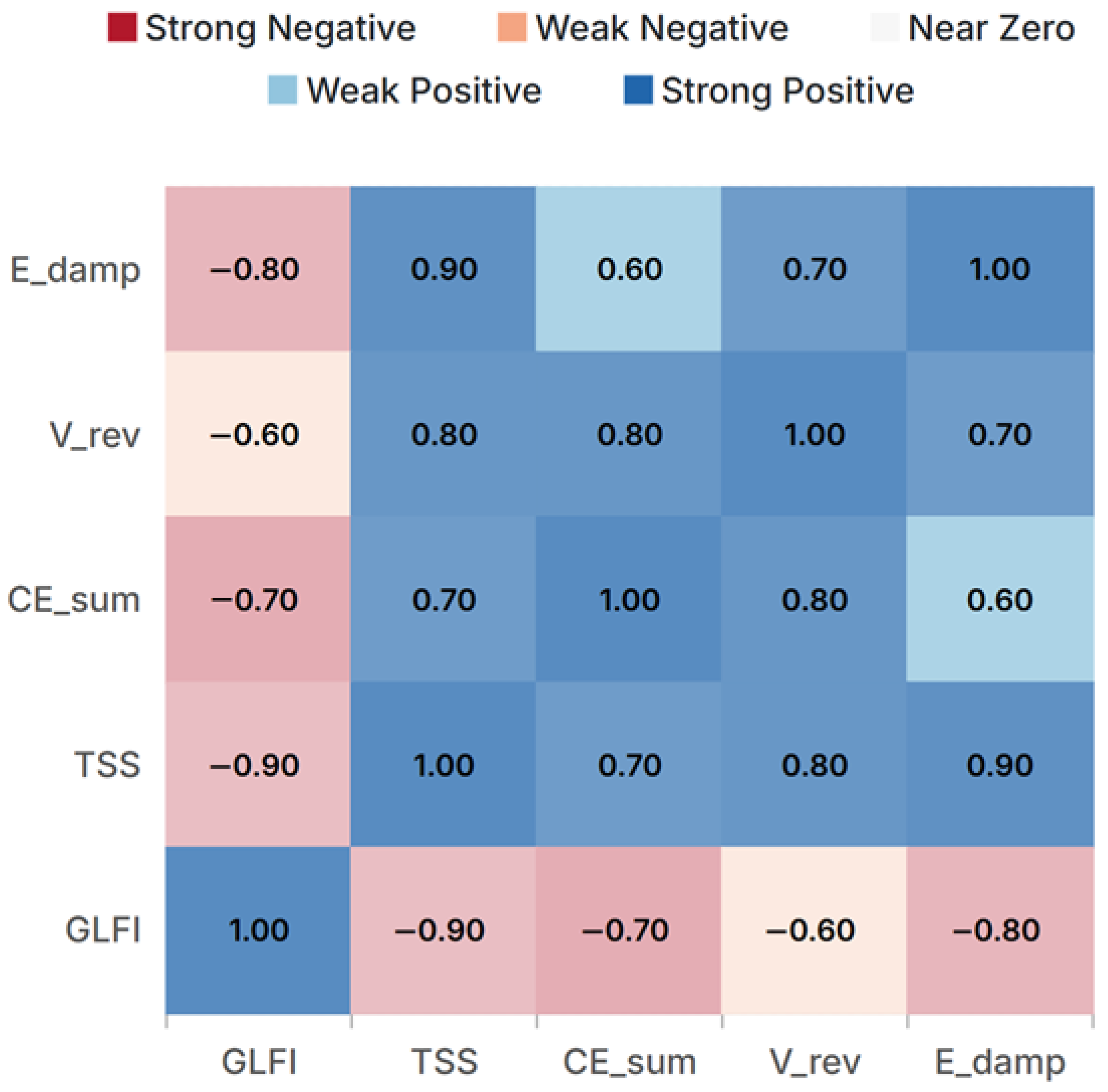

Figure 4.

Deterministic Pearson association matrix across the fixed scenario × controller catalog. KPI codes: GLFI (Grid Load-Following Index), TSS (Transient Severity Score), (cumulative actuation effort), Vrev (valve reversals), and (modal damping energy proxy).

Figure 4.

Deterministic Pearson association matrix across the fixed scenario × controller catalog. KPI codes: GLFI (Grid Load-Following Index), TSS (Transient Severity Score), (cumulative actuation effort), Vrev (valve reversals), and (modal damping energy proxy).

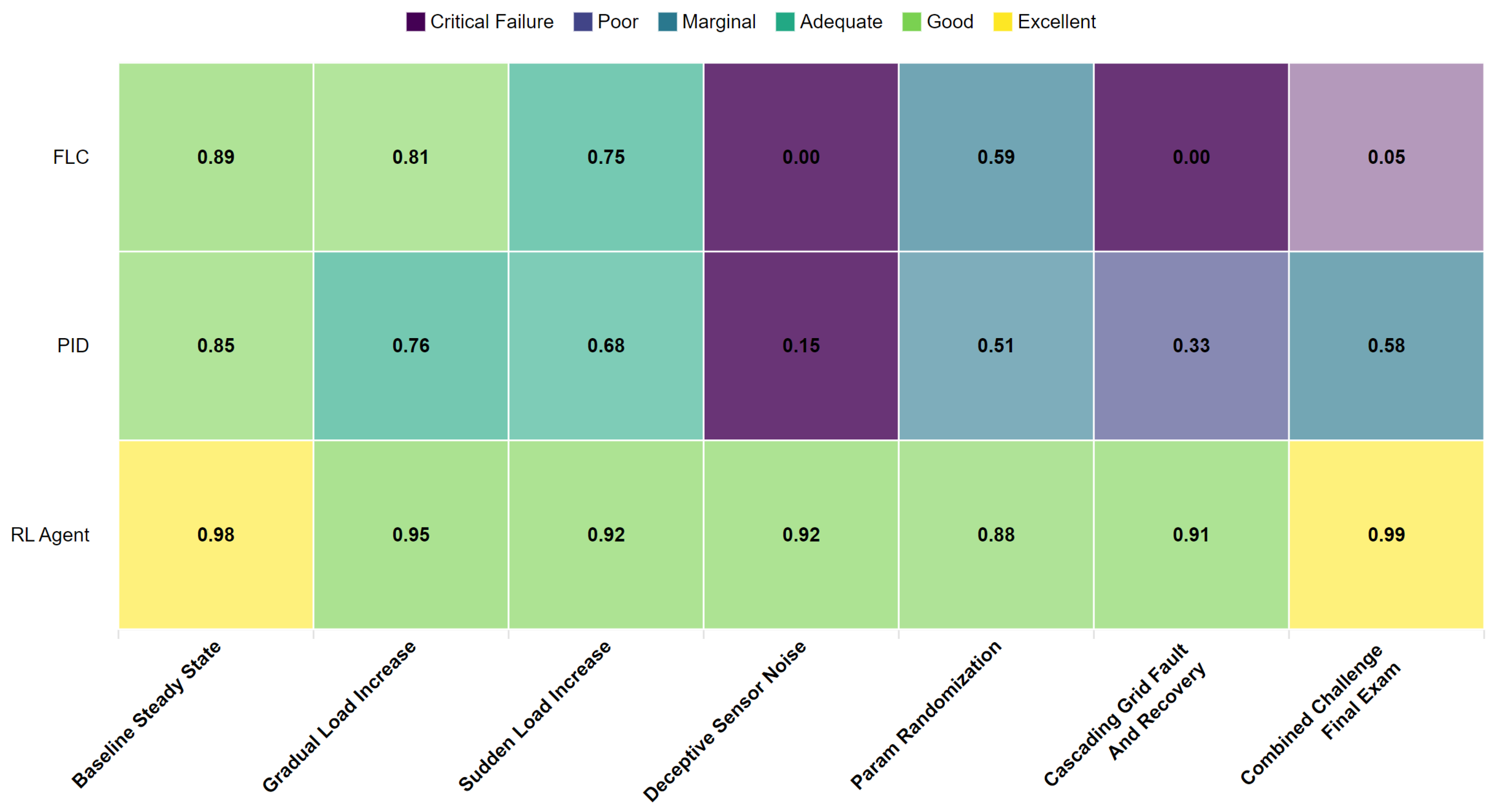

Figure 5.

Scenario × controller performance heatmap. Higher is better. “FAIL” indicates a violation of deterministic gates.

Figure 5.

Scenario × controller performance heatmap. Higher is better. “FAIL” indicates a violation of deterministic gates.

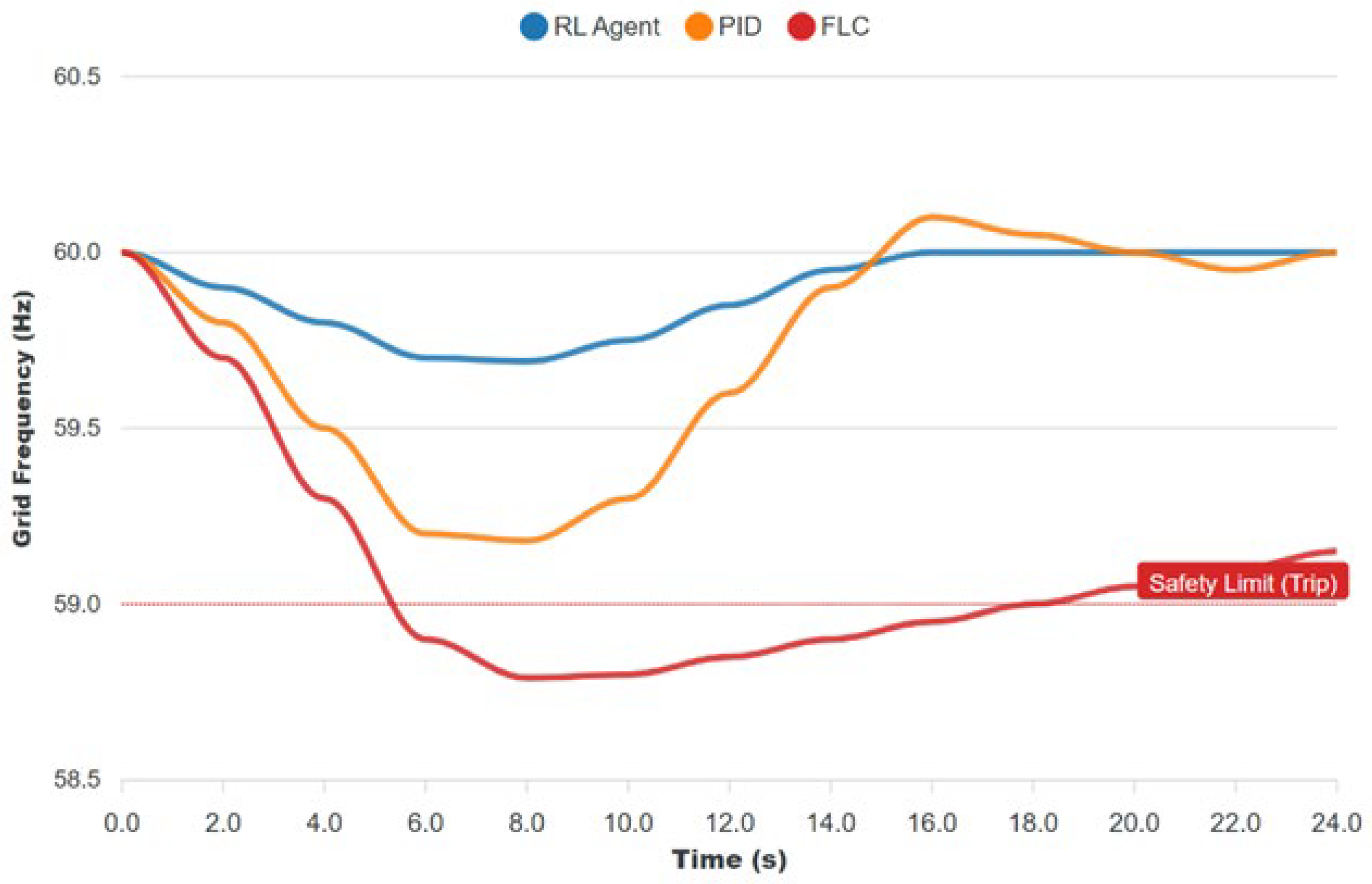

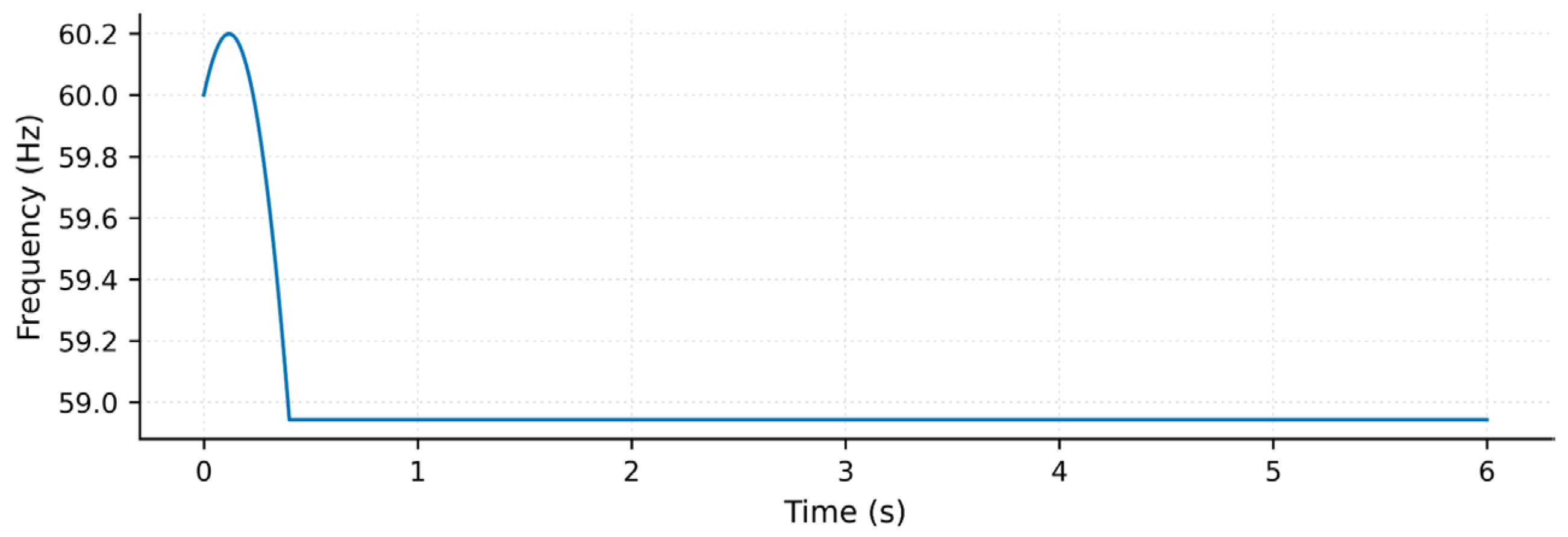

Figure 6.

Frequency response under a hard event; the dotted line denotes the trip limit. The SAC maintains a higher nadir and converges faster.

Figure 6.

Frequency response under a hard event; the dotted line denotes the trip limit. The SAC maintains a higher nadir and converges faster.

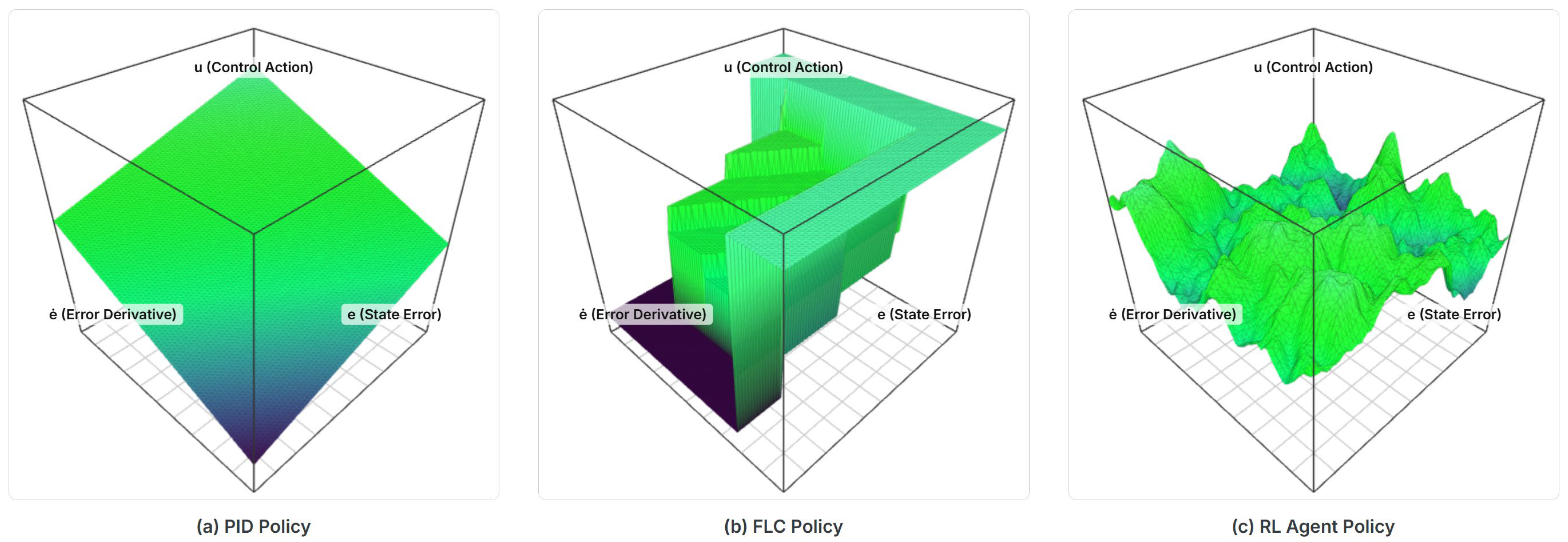

Figure 7.

Policy manifolds in a common (e, de/dt) projection: (a) PID (planar), (b) FLC (piecewise), and (c) SAC (smooth, adaptive).

Figure 7.

Policy manifolds in a common (e, de/dt) projection: (a) PID (planar), (b) FLC (piecewise), and (c) SAC (smooth, adaptive).

Figure 8.

Performance-to-effort ratio Π across scenarios. The SAC maintains the highest economy across the entire catalog.

Figure 8.

Performance-to-effort ratio Π across scenarios. The SAC maintains the highest economy across the entire catalog.

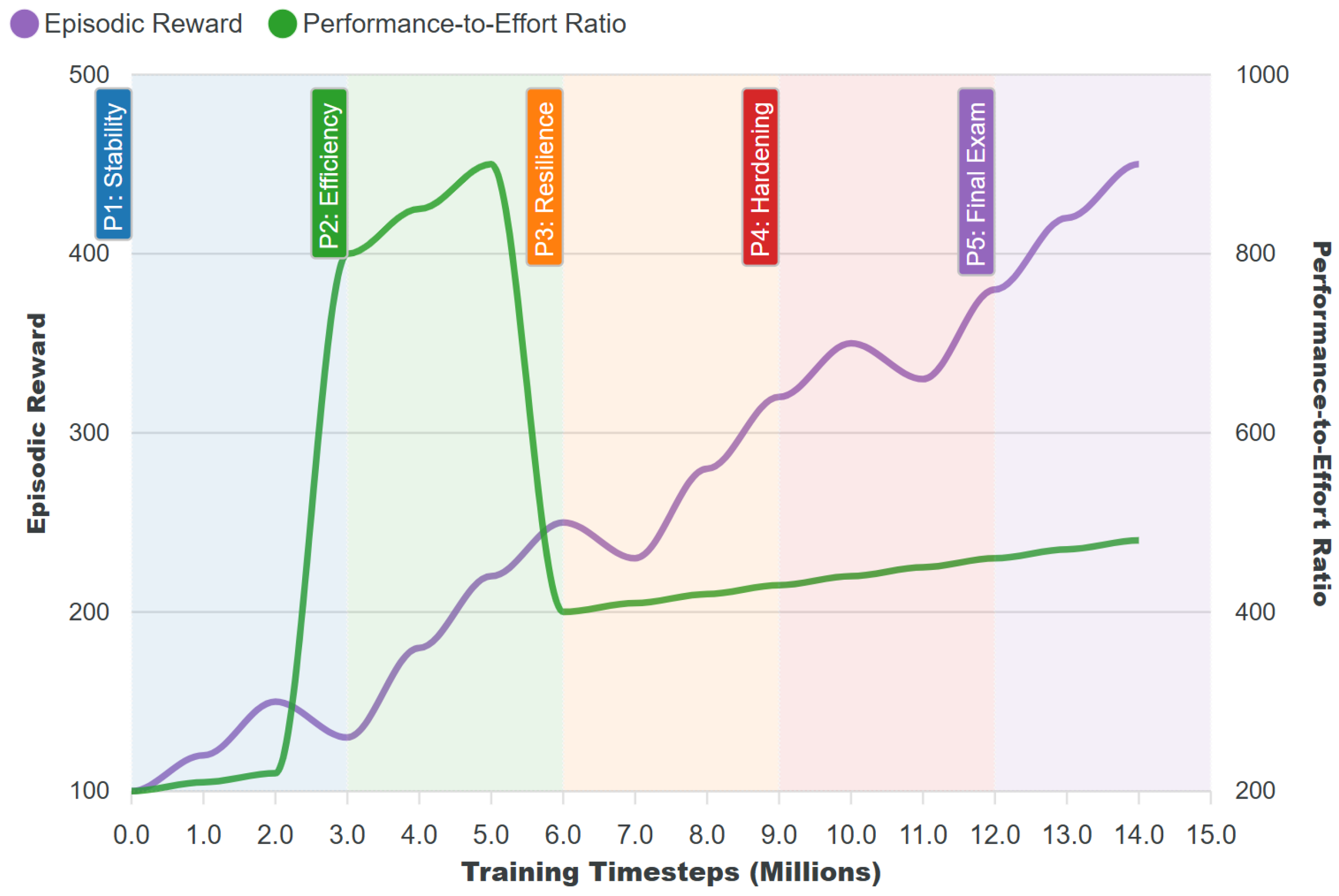

Figure 9.

Training provenance for the released SAC policy over curriculum phases P1–P5, evaluated on the fixed catalog.

Figure 9.

Training provenance for the released SAC policy over curriculum phases P1–P5, evaluated on the fixed catalog.

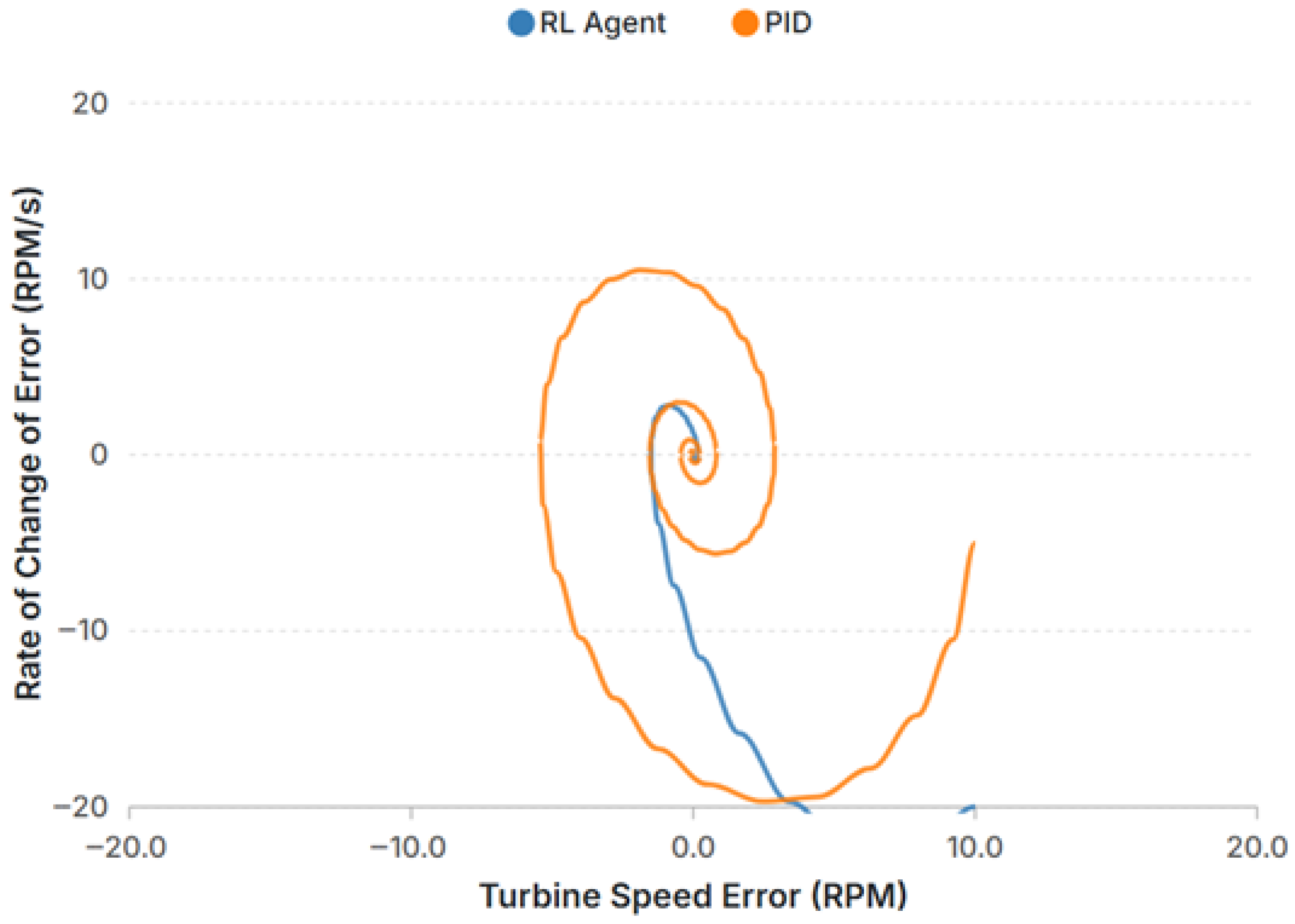

Figure 10.

Phase portrait (Δω vs. d(Δω)/dt) for the SAC and PID. The SAC contracts monotonically; the PID follows spiral trajectories indicative of under-damping.

Figure 10.

Phase portrait (Δω vs. d(Δω)/dt) for the SAC and PID. The SAC contracts monotonically; the PID follows spiral trajectories indicative of under-damping.

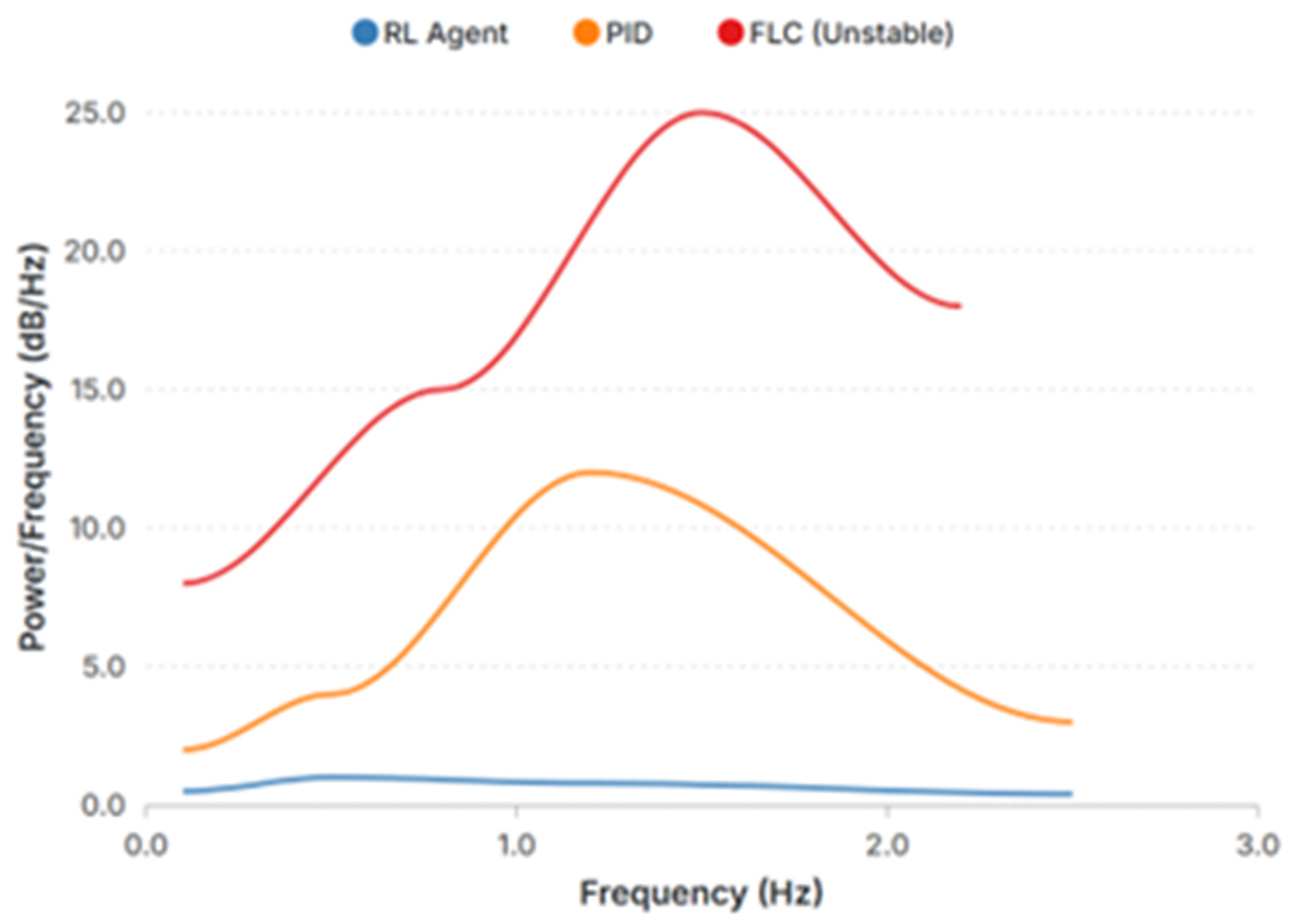

Figure 11.

Power spectral density of Δf. The SAC actively suppresses energy near the dominant mode compared with the PID and FLC.

Figure 11.

Power spectral density of Δf. The SAC actively suppresses energy near the dominant mode compared with the PID and FLC.

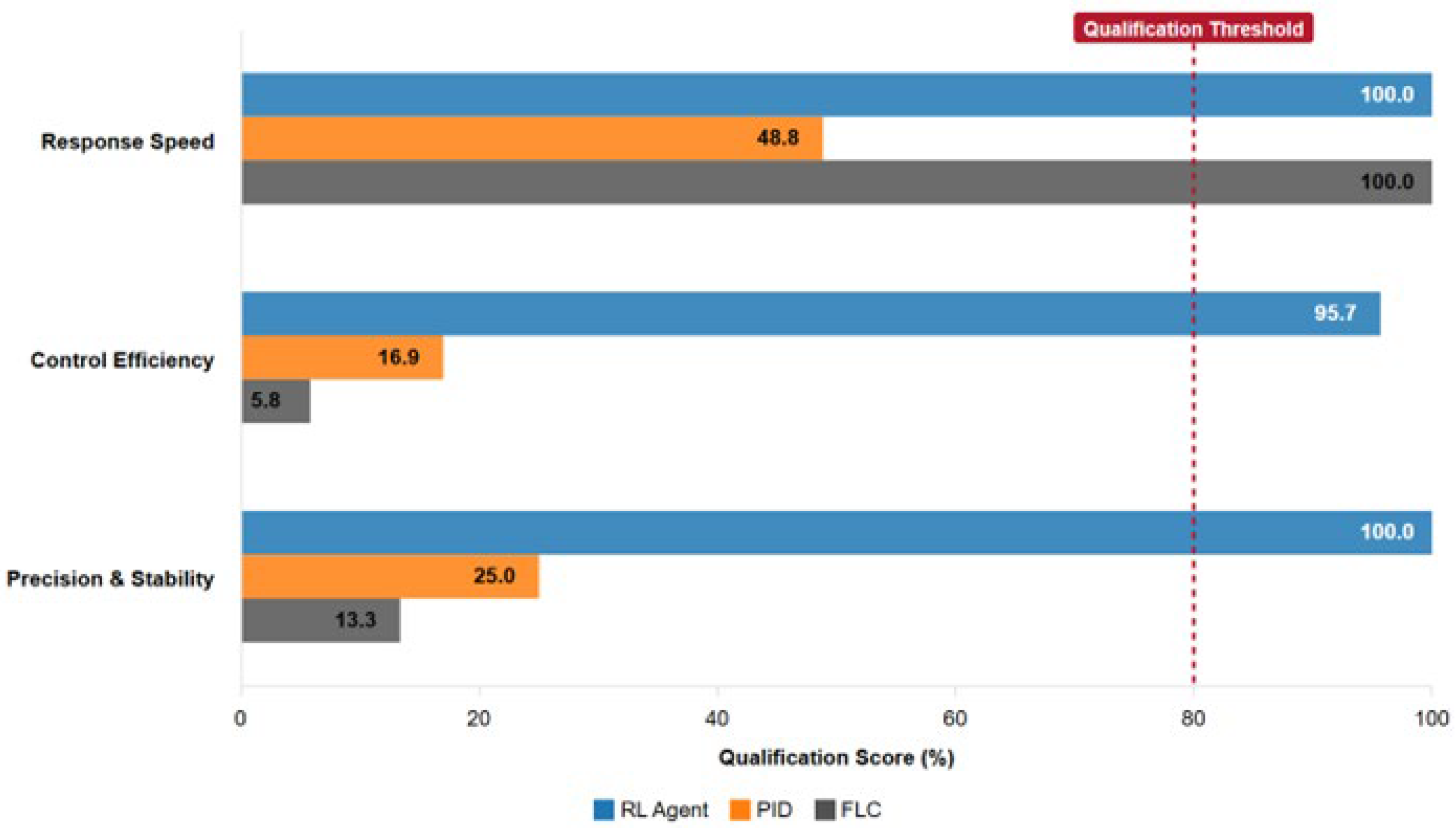

Figure 12.

Ancillary-services qualification scorecard (deterministic). The vertical dashed line denotes the qualification threshold.

Figure 12.

Ancillary-services qualification scorecard (deterministic). The vertical dashed line denotes the qualification threshold.

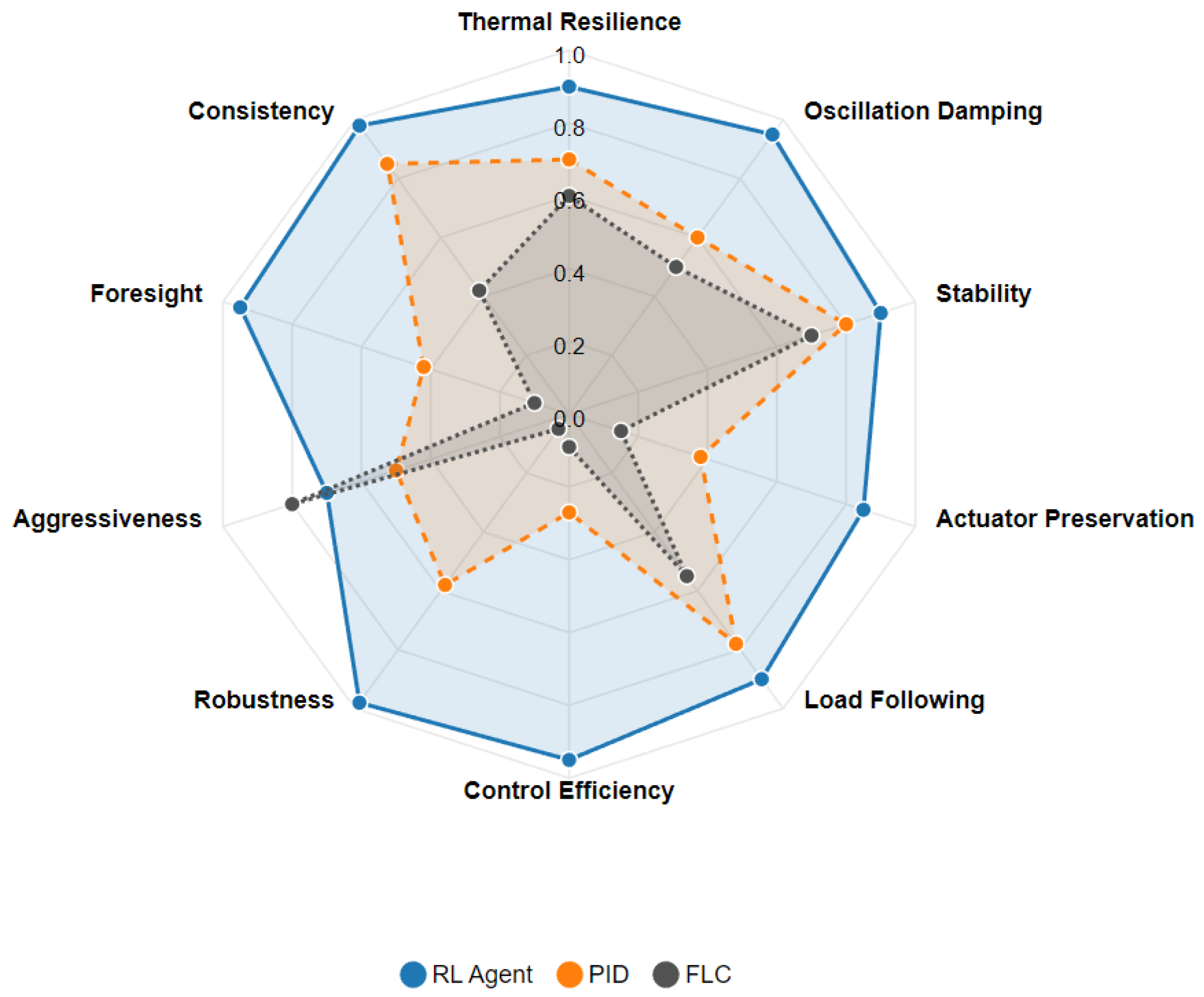

Figure 13.

Multi-attribute performance profile, with archetypal radar synthesis.

Figure 13.

Multi-attribute performance profile, with archetypal radar synthesis.

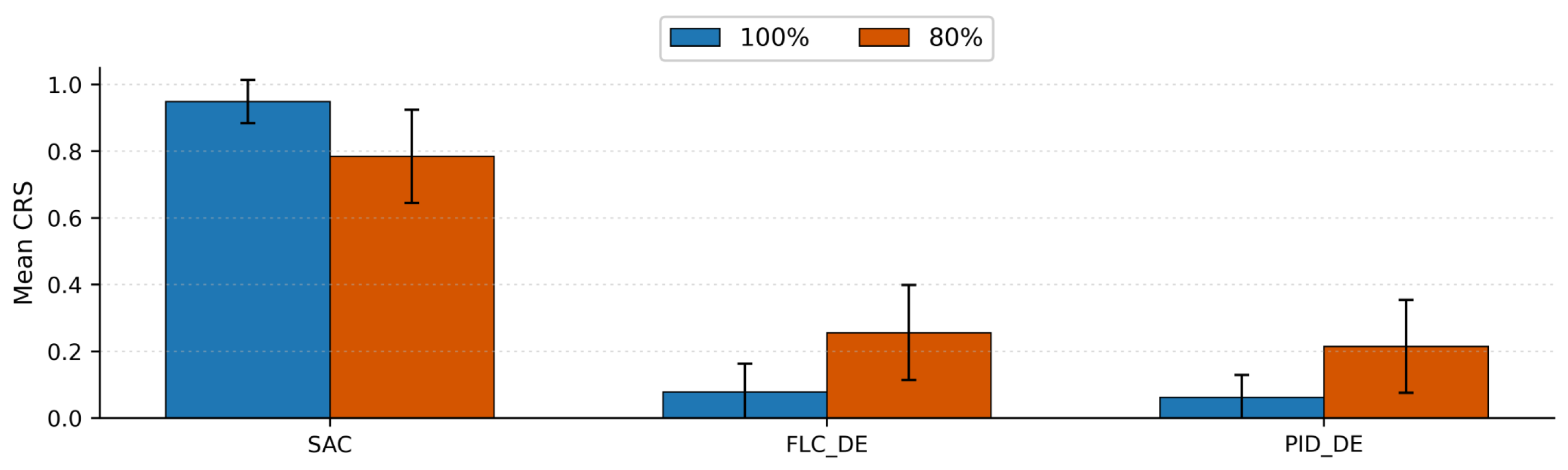

Figure 14.

Cross-scenario Controller Robustness Scores (CRSs, mean ±95% CI) for the SAC, FLC_DE, and PID_DE at two power levels (100% blue; 80% orange). The SAC maintains a near-unity CRS at both levels, while baseline controllers remain below 0.3 on average at 100% power and improve modestly at 80%. Error bars reflect variability across seeds and scenarios (n = 24 per bar).

Figure 14.

Cross-scenario Controller Robustness Scores (CRSs, mean ±95% CI) for the SAC, FLC_DE, and PID_DE at two power levels (100% blue; 80% orange). The SAC maintains a near-unity CRS at both levels, while baseline controllers remain below 0.3 on average at 100% power and improve modestly at 80%. Error bars reflect variability across seeds and scenarios (n = 24 per bar).

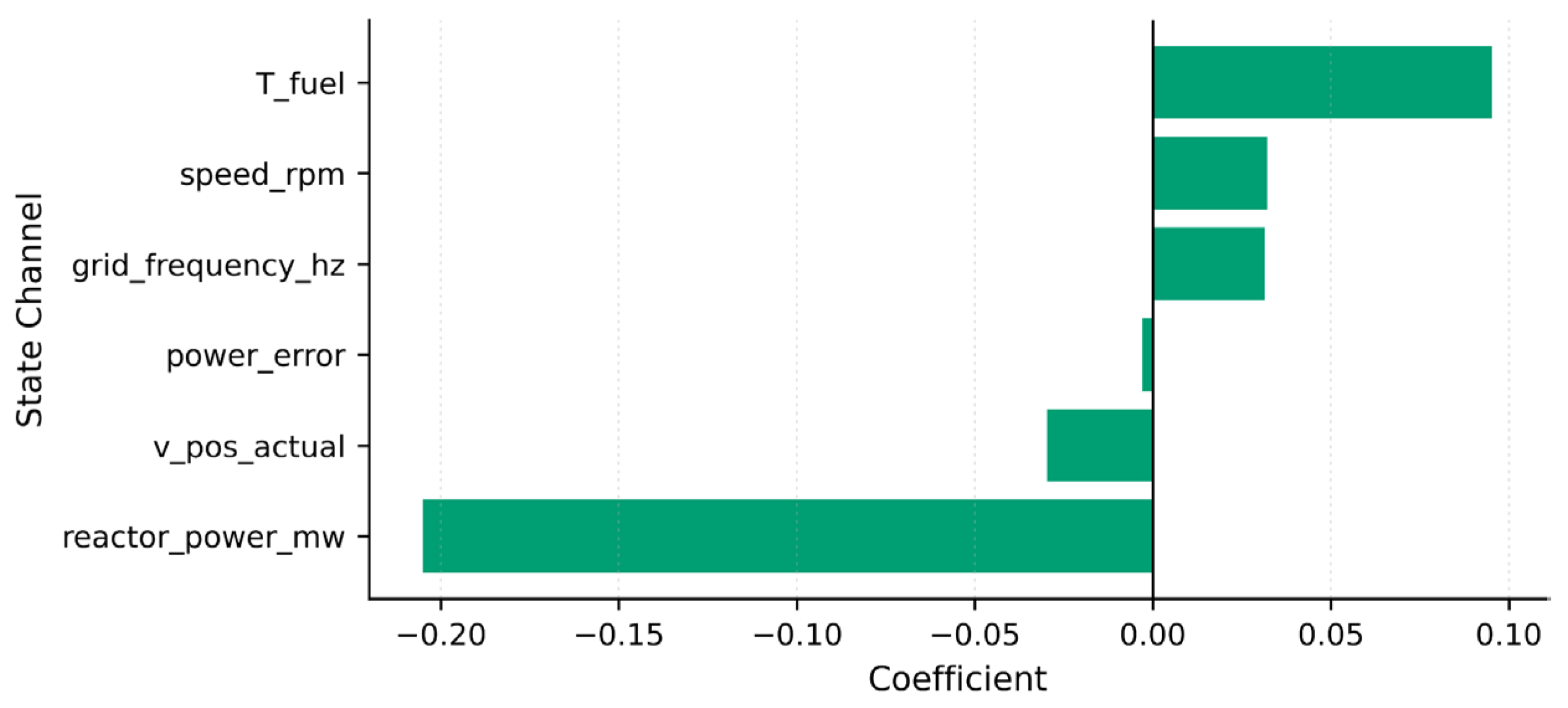

Figure 15.

Local linear surrogate of the SAC policy around a critical operating context. Positive loadings (right) increase the SAC action; negative loadings (left) decrease it. The surrogate highlights the dominant channels: a large negative weight on reactor_power_mw and strong positive weight on T_fuel, with secondary contributions from grid_frequency_hz and speed_rpm. This mechanistic view explains the SAC’s stabilizing reactions without resorting to opaque end-to-end reasoning.

Figure 15.

Local linear surrogate of the SAC policy around a critical operating context. Positive loadings (right) increase the SAC action; negative loadings (left) decrease it. The surrogate highlights the dominant channels: a large negative weight on reactor_power_mw and strong positive weight on T_fuel, with secondary contributions from grid_frequency_hz and speed_rpm. This mechanistic view explains the SAC’s stabilizing reactions without resorting to opaque end-to-end reasoning.

Figure 16.

SAC action-entropy proxy over time during a representative disturbance. Exploration collapses within ~0.6 s, after a brief transient peak (≈0.40), indicating confident, low-variance actuation once the operating point re-enters the admissible band.

Figure 16.

SAC action-entropy proxy over time during a representative disturbance. Exploration collapses within ~0.6 s, after a brief transient peak (≈0.40), indicating confident, low-variance actuation once the operating point re-enters the admissible band.

Figure 17.

Critical contexts (T2): pairwise action comparison at time points with elevated system risk. Bars report normalized actuation magnitudes for the SAC, PID, and FLC at multiple timestamps. The SAC consistently applies the least aggressive input compatible with risk reduction, especially near t ≈ 4.0–4.06 s, while the PID/FLC remain saturated. This selective restraint aligns with the entropy trace and explains the SAC’s superior CRS.

Figure 17.

Critical contexts (T2): pairwise action comparison at time points with elevated system risk. Bars report normalized actuation magnitudes for the SAC, PID, and FLC at multiple timestamps. The SAC consistently applies the least aggressive input compatible with risk reduction, especially near t ≈ 4.0–4.06 s, while the PID/FLC remain saturated. This selective restraint aligns with the entropy trace and explains the SAC’s superior CRS.

Table 1.

Neutron kinetics constants.

Table 1.

Neutron kinetics constants.

| Symbol | Description | Value | Units |

|---|

| β | Total delayed neutron fraction | 0.006502 | - |

| Λ | Prompt neutron generation time | 1.0 × 10−4 | s |

| Precursor decay constant (group 1) | 0.0124 | s−1 |

| Precursor decay constant (group 2) | 0.0305 | s−1 |

| λ3 | Precursor decay constant (group 3) | 0.111 | s−1 |

| λ4 | Precursor decay constant (group 4) | 0.301 | s−1 |

| Precursor decay constant (group 5) | 1.14 | s−1 |

| Precursor decay constant (group 6) | 3.01 | s−1 |

Table 2.

Delayed neutron fractions per group (six-group; sum to β).

Table 2.

Delayed neutron fractions per group (six-group; sum to β).

| Symbol | Description | Value | Units |

|---|

| Group-1 delayed neutron fraction | 0.000215 | - |

| Group-2 delayed neutron fraction | 0.001424 | - |

| Group-3 delayed neutron fraction | 0.001274 | - |

| Group-4 delayed neutron fraction | 0.002568 | - |

| Group-5 delayed neutron fraction | 0.000748 | - |

| Group-6 delayed neutron fraction | 0.000273 | - |

Table 3.

Thermal–hydraulic and power-mapping constants.

Table 3.

Thermal–hydraulic and power-mapping constants.

| Symbol | Description | Value | Units |

|---|

| κP | Power scaling (n → MW_th) | 1000.0 | MW |

| Cf | Effective fuel thermal capacity | 30.0 | MJ/°C |

| Cc | Effective coolant thermal capacity | 50.0 | MJ/°C |

| Ufc | Fuel-coolant conductance | 2.0 | MW/°C |

| Ucs | Coolant-secondary conductance | 20.0 | MW/°C |

| Ts0 | Secondary-side sink temperature (fixed) | 270.0 | °C |

Table 4.

Turbine-governor and grid constants.

Table 4.

Turbine-governor and grid constants.

| Symbol | Description | Value | Units |

|---|

| τv | Valve servo time constant | 0.30 | s |

| τm | Steam-path/turbine lag | 3.0 | s |

| Kt | Turbine gain (v → P_m) | 900.0 | MW/- |

| ηg | Generator efficiency | 0.98 | - |

| fnom | Nominal grid frequency | 60.0 | Hz |

| Pref | Nominal electrical power reference | 600.0 | MW |

Table 5.

Actuator limits and numerical step.

Table 5.

Actuator limits and numerical step.

| Symbol | Description | Value | Units |

|---|

| Valve lower bound | 0.0 | - |

| Valve upper bound | 1.0 | - |

| Valve rate limit | 0.15 | s−1 |

|

Δt | Numerical integration step | 0.05 | s |

Table 6.

PID parameters.

| Symbol | Description | Value | Units |

|---|

| Proportional gain | 1.800 | - |

| Integral gain | 0.300 | s−1 |

| Kd | Derivative gain | 0.050 | s |

| τd | Derivative filter time constant | 0.200 | s |

| Valve lower bound | 0.0 | - |

| Valve upper bound | 1.0 | - |

| Valve rate limit | 0.15 | s−1 |

|

Δt | Loop period (numerical step) | 0.05 | s |

Table 7.

FLC rule base (rows: Δe; columns: e).

Table 7.

FLC rule base (rows: Δe; columns: e).

| Δe\e | NB | NS | ZE | PS | PB |

|---|

| NB | PB | PB | PS | ZE | ZE |

| NS | PB | PS | ZE | NS | ZE |

| ZE | PS | ZE | ZE | ZE | NS |

| PS | ZE | NS | ZE | NS | NB |

| PB | ZE | ZE | NS | NB | NB |

Table 8.

FLC scaling parameters.

Table 8.

FLC scaling parameters.

| Symbol | Description | Value | Units |

|---|

| se | Error scaling | 1.50 | - |

| s{Δe} | Error-rate scaling | 0.80 | - |

| su | Output scaling | 0.35 | - |

Table 9.

Normalized triangular MF breakpoints for antecedents (centers at −1, −0.5, 0, 0.5, and 1; ~50% overlap; clamped to [−1, 1]).

Table 9.

Normalized triangular MF breakpoints for antecedents (centers at −1, −0.5, 0, 0.5, and 1; ~50% overlap; clamped to [−1, 1]).

| Label | a | b | c |

|---|

| NB | −1.00 | −1.00 | −0.50 |

| NS | −1.00 | −0.50 | 0.00 |

| ZE | −0.50 | 0.00 | 0.50 |

| PS | 0.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 |

| PB | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Table 10.

Normalization scales and safety thresholds (deterministic).

Table 10.

Normalization scales and safety thresholds (deterministic).

| Symbol | Quantity | Value | Units | Notes |

|---|

| SP | Reactor power (scale) | 1000.0 | MW | Normalization divisor for P |

| ST | Fuel temperature (scale) | 1000.0 | °C | Normalization divisor for T_fuel |

| Sf | Grid frequency (scale) | 1.0 | Hz | Normalization divisor for f |

| Sω | Rotor speed (scale) | 1.0 | pu | Normalization divisor for ω |

| f{trip} | Under-frequency trip gate | 49.00 | Hz | Hard safety gate |

| Calm band (frequency) | 0.02 | Hz | Calm multiplier applies if ≤ value |

| Calm band (power) | 2.0 | MW | Calm multiplier applies if ≤ value |

Table 11.

Reward weights and bonuses (dimensionless).

Table 11.

Reward weights and bonuses (dimensionless).

| Symbol | Description | Value | Units | Notes |

|---|

| wf | Frequency error penalty | 1.00 | - | Primary stability focus |

| w{move} | Valve movement penalty | 0.010 | - | Economy and wear proxy |

| w{jerk} | Valve jerk penalty | 0.020 | - | Penalizes reversals |

| w{bonus} | Safe completion bonus | 5.00 | - | Applied once if no gates breached |

| w{unsafe} | Unsafe penalty | 10.00 | - | Applied on any gate violation |

| c{calm} | Calm-state multiplier | 0.50 | - | If |Δf| ≤ 0.02 Hz and |ΔP| ≤ 2 MW |

Table 12.

Deterministic curriculum phases and promotion conditions.

Table 12.

Deterministic curriculum phases and promotion conditions.

| Symbol | Phase | Scenario Bundle | Promotion Threshold | Reward Overrides |

|---|

| P1 | Stability and limits | Baseline; ramp-in-place | Nunsafe = 0; non-decreasing ravg | Increasing ↑ wf; enable calm multiplier |

| P2 | Efficiency | Baseline; gradual load | Nunsafe = 0; non-decreasing ravg | Increasing ↑ wmove |

| P3 | Disturbances I | Sensor-noise; parameter ramp (deterministic) | Nunsafe _{unsafe} = 0; non-decreasing ravg | Increasing ↑ wjerk |

| P4 | Disturbances II | Cascading-fault | Nunsafe = 0; non-decreasing ravg | Keep P2/P3 overrides |

| P5 | Final exam | Combined | Nunsafe = 0; non-decreasing ravg | Freeze weights; evaluate only |

Table 13.

SAC hyperparameters (values used).

Table 13.

SAC hyperparameters (values used).

| Symbol | Name | Value | Units | Notes |

|---|

| α | Entropy temperature | auto-tuned | - | Target entropy heuristic |

| γ | Discount factor | 0.99 | - | Stable defaults |

| τ | Polyak rate | 0.005 | - | Target critic averaging |

| ηQ | Critic learning rate | 3 × 10−4 | - | Adam |

| ηπ | Actor learning rate | 3 × 10−4 | - | Adam |

| ηα | Temperature learning rate | 3 × 10−4 | - | If α learnable |

| B | Batch size | 1024 | samples | Minibatch size |

| |D| | Replay capacity | 1,200,000 | transitions | FIFO |

| N0 | Learning starts | 120,000 | steps | Warm-up |

| T | Total timesteps | 15,000,000 | steps | Training budget |

| feval | Evaluation frequency | 80,000 | steps | Deterministic evals |

| policy | Policy/widths | MlpPolicy/[512,512] | - | Hidden units |

Table 14.

Replay/batch schedule and evaluation settings.

Table 14.

Replay/batch schedule and evaluation settings.

| Symbol | Quantity | Value | Units | Notes |

|---|

| tstep | Environment step time | Δt | s | Loop period from plant interface |

| Nupdate | Updates per env step | 1 | - | Once learning starts |

| Ntarget | Target update cadence | 1 | - | Per gradient step |

| evaldet | Deterministic evaluation | enabled | - | No exploration noise |

Table 15.

Metric weights used in J(θ).

Table 15.

Metric weights used in J(θ).

| Symbol | Metric | Group | Weight | Notes |

|---|

| wTSS | Transient Severity Score (TSS) | M ↓ | 1.00 | Primary stability objective |

| wCE | Cumulative actuation effort (CEsum) | M ↓ | 0.50 | Economy objective |

| wVrev | Valve reversals (Vrev) | M ↓ | 0.50 | Mechanical wear proxy |

| wGLFI | Grid Load-Following Index (GLFI) | M ↑ | 1.00 | Tracking quality |

| λ | Failure penalty multiplier | 100 | — | Scaled by Nfail (θ) |

Table 16.

DE bounds and algorithm parameters.

Table 16.

DE bounds and algorithm parameters.

| Symbol | Parameter | Bounds/Value | Units | Notes |

|---|

| Kp | PID proportional gain | [0.5, 3.0] | - | Search bound |

| Ki | PID integral gain | [0.05, 0.8] | s−1 | Search bound |

| Kd | PID derivative gain | [0.00, 0.15] | s | Search bound |

| τd | Derivative time constant | [0.05, 0.50] | s | Search bound |

| se | FLC error scale | [0.5, 2.5] | - | Search bound |

| sΔe | FLC error-rate scale | [0.3, 1.5] | - | Search bound |

| su | FLC output scale | [0.1, 0.8] | - | Search bound |

| F | DE mutation scale | [0.5, 1.0] | - | Differential weight |

| Cr | DE crossover probability | 0.7 | - | Crossover rate |

| Gmax | Max iterations | 50 (PID)/30 (FLC) | generations | Stopping criterion |

| P | Population size | 15 | candidates | Per generation |

| tol | Convergence tolerance | 1 × 10−2 | - | Early stop threshold |

Table 17.

Evidence artifacts emitted by the pipeline.

Table 17.

Evidence artifacts emitted by the pipeline.

| Symbol | Artifact | Path/Identifier | Frequency | Mechanism |

|---|

| A1 | Raw evaluation logs | results/logs/*.csv | Per eval | Auto-export |

| A2 | Training checkpoints | results/checkpoints/*.zip | Per save step | SB3 saver |

| A3 | Best model | results/best/*.zip | On improvement | Eval callback |

| A4 | Final model | results/final/*.zip | End of training | Export final |

| A5 | Reports/figures | results/reports/* | On demand | Figure scripts |

| A6 | Config manifests | results/config/*.yml | Per run | Hash-locked |

Table 19.

Safety gates and constants (deterministic).

Table 19.

Safety gates and constants (deterministic).

| Symbol | Description | Value | Units |

|---|

| Under-frequency trip threshold | 49.00 | Hz |

| Max rotor speed (per-unit) | 1.10 | pu |

| Fuel temperature limit | 1500 | °C |

Table 22.

CRS weights and licensing thresholds (dimensionless unless noted).

Table 22.

CRS weights and licensing thresholds (dimensionless unless noted).

| Symbol | Description | Value | Units/Notes |

|---|

| w safe | Safety contribution in CRS | 0.40 | - |

| w tss _{tss} | Transient severity contribution in CRS | 0.30 | - |

| w eff | Control-effort contribution in CRS | 0.15 | - |

| w glfi | Tracking contribution in CRS | 0.15 | - |

| Minimum acceptable GLFI | 0.90 | - |

| Upper bound on TSS | 1.00 | - |

| Max rotor-speed overshoot | 5 | % |

Table 23.

Entropy band constants.

Table 23.

Entropy band constants.

| Symbol | Description | Value | Units |

|---|

| H{min} | Lower entropy bound | 0.10 | nats |

| H{max} | Upper entropy bound | 2.00 | nats |

Table 24.

Portfolio constants (dimensionless unless noted).

Table 24.

Portfolio constants (dimensionless unless noted).

| Symbol | Description | Value | Units |

|---|

| S | Number of scenarios | 8 | - |

| Minimum acceptable mean CRS | 0.90 | - |

Table 25.

Evidence artifacts (deterministic assurance pack).

Table 25.

Evidence artifacts (deterministic assurance pack).

| ID | Path/Naming | Role |

|---|

| A1 | results/logs/*.csv | Raw timeseries traces per scenario |

| A2 | results/metrics/*.csv | Per-scenario metric tables (GLFI, TSS, CE sum, Vrev, , TTU) |

| A3 | results/checkpoints/best/*.zip | Best controller snapshot (by mean CRS) |

| A4 | results/checkpoints/final/*.zip | Final controller snapshot (end of training) |

| A5 | results/reports/*.md | Auto-generated markdown reports and summaries |

| A6 | results/config/*.yml | Versioned configuration and constants manifest |

| Symbol | Description | Value | Units/Derivation |

|---|

| T | Evaluation horizon | 600 | s (scenario constant) |

|

Δt | Controller/eval step | 0.05 | s (scenario constant) |

| N | Samples per episode | 12,000 | — (T/Δt) |

| r{max} | Valve rate limit | 0.15 | s−1 (from Section 3.2) |

| CE{abs,max} | Max cumulative movement | 90 | (r_{max}·T) |

| V{rev,max} | Max valve reversals | 11,998 | count (N − 2) |

| GLFI{min} | Minimum acceptable GLFI | 0.90 | (Table 22) |

| TSS{lim} | Upper bound on TSS | 1.00 | (Table 22) |

| OS{\omega,max} | Max rotor-speed overshoot | 5 | % (Table 22) |

| H{min}, H{max} | Entropy band | 0.10, 2.00 | nats (Table 23) |

| CRS{min} | Minimum acceptable mean CRS | 0.90 | — (Table 24) |

Table 18.

Scenario parameters (deterministic values).

Table 18.

Scenario parameters (deterministic values).

| Symbol | Description | Value | Units |

|---|

| T | Evaluation horizon | 600 | s |

| Δt | Controller/eval step | 0.05 | s |

| fnom | Nominal grid frequency | 60.0 | Hz |

| Reference load change magnitude | 0.04·P_{ref} | MW |

| t1, t2 | Gradual ramp window | 120, 300 | s |

| ts(s) | Sudden step time | 60 | s |

| Fault window #1 | 120, 210 | s |

| Fault window #2 | 360, 420 | s |

| , | Frequency-noise amplitudes | 0.003, 0.002 | Hz |

| Noise tones (frequency) | 0.6, 1.2 | Hz |

| Φ2 | Noise phase | 1.0472 | rad (≈60°) |

Table 20.

Metric normalization constants (fixed).

Table 20.

Metric normalization constants (fixed).

| Symbol | Description | Value | Units | Derivation |

|---|

| rmax | Valve rate limit | 0.15 | s−1 | From Section 3.2 PID/limits |

| T | Evaluation horizon | 600 | s | Scenario constant |

| N | Samples per episode | 12,000 | - | T/Δt with Δt = 0.05 s |

| Max cumulative movement | 90 | - | ·T |

| Max valve reversals | 11,998 | count | N − 2 |

| GLFI denominator floor | 1.0 | MW | Physical floor |

| ω1, ω2 | PSD band (rad/s) | 3.14, 12.57 | rad/s | 0.5–2.0 Hz |

Table 21.

TSS weights and limits (dimensionless).

Table 21.

TSS weights and limits (dimensionless).

| Symbol | Description | Value | Units |

|---|

| Frequency-error weight | 0.50 | - |

| wce | Control-effort weight | 0.20 | - |

| Valve-reversal weight | 0.20 | - |

| Overshoot weight | 0.10 | - |

| IAE_f normalization | 60 | Hz·s |

| Overshoot limit | 5 | % |

Table 27.

Concise positioning of this study relative to the two suggested works.

Table 27.

Concise positioning of this study relative to the two suggested works.

| Study | System/Task | Primary KPIs | Safety/

Licensing Gates | Deterministic Replay | Traceability

Artifacts | Relevance to Present

Results |

|---|

| Zhang et al. (2024) [26] | Regional multi-energy market-clearing with hierarchical RL | Market matching efficiency; economic outcomes | Not reported | Case-study simulations | Not reported | Algorithmic/architectural RL advance for markets; different objective class |

| Yang et al. (2023) [27] | Island-group energy management under transmission constraints with hybrid policy RL | Operational cost; energy-balance KPIs | Not reported | Simulation studies | Not reported | System-level management focus; different KPIs and constraints |

| This study | PWR governor control (load-following) with SAC vs. DE-tuned PID/FLC | Gate pass rate; TTU, GLFI, TSS; overshoot; control effort; CRS | Yes—explicit, licensing-aligned | Yes—adversarial, fixed-replay portfolio | Yes—critical state–action mapping, critical pairs, sensitivity | Licensing-grade assurance for safety-critical plant control |

Table 28.

Matrixed mapping towards industrial towards industrial adaptation.

Table 28.

Matrixed mapping towards industrial towards industrial adaptation.

| Limitation (Current) | Deterministic Upgrade | New Evidence Artifact | Gate/KPI Addition | Target Environment |

|---|

| Infinite-bus grid | Multi-area RO models + PMU replay | Mode-damping logs, ROCOF checks | Inter-area damping KPI | Real-time sim/HIL |

| TH surrogate | Multi-node TH + DNBR | Margin envelopes per scenario | Thermal-limit gates | High-fidelity twin |

| No HIL | PLC/RTOS with latency and watchdog | Timing budgets, watchdog logs | Timing-budget gate | HIL bench |

| Limited baselines | Add MPC/H∞/LQR | Controller-agnostic scorecards | Portfolio gates unchanged | Twin/HIL |

| No RTA/CBF | Simplex + control-barrier functions | Intervention/dwell logs | RTA-intervention gate | Twin/HIL |

| No formal proofs | Reachability/STL | Certificates + counterexamples | Certificate-presence gate | Twin |

| No uncertainty envelopes | Structured sweeps | Worst-case KPI tables | Envelope-completeness gate | Twin/HIL |

| No fault drills | Dropout/stiction/stuck-valve | Recovery timelines | Fault-recovery gate | Twin/HIL |

| No HSI drills | Operator-in-the-loop runs | Workload/trust metrics | Human-override gate | HIL |

| No cyber drills | Spoof/tamper/DoS tests | Detect/mitigate traces | Cyber-resilience gate | Segmented testbed |