A Hierarchical Control Framework for HVAC Systems: Day-Ahead Scheduling and Real-Time Model Predictive Control Co-Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Literature Review

1.2.1. Building Cooling Load Prediction Models

1.2.2. HVAC System Optimization and Control Strategies

1.2.3. MPC in Building Energy Systems

1.3. Research Objectives and Contributions

- (1)

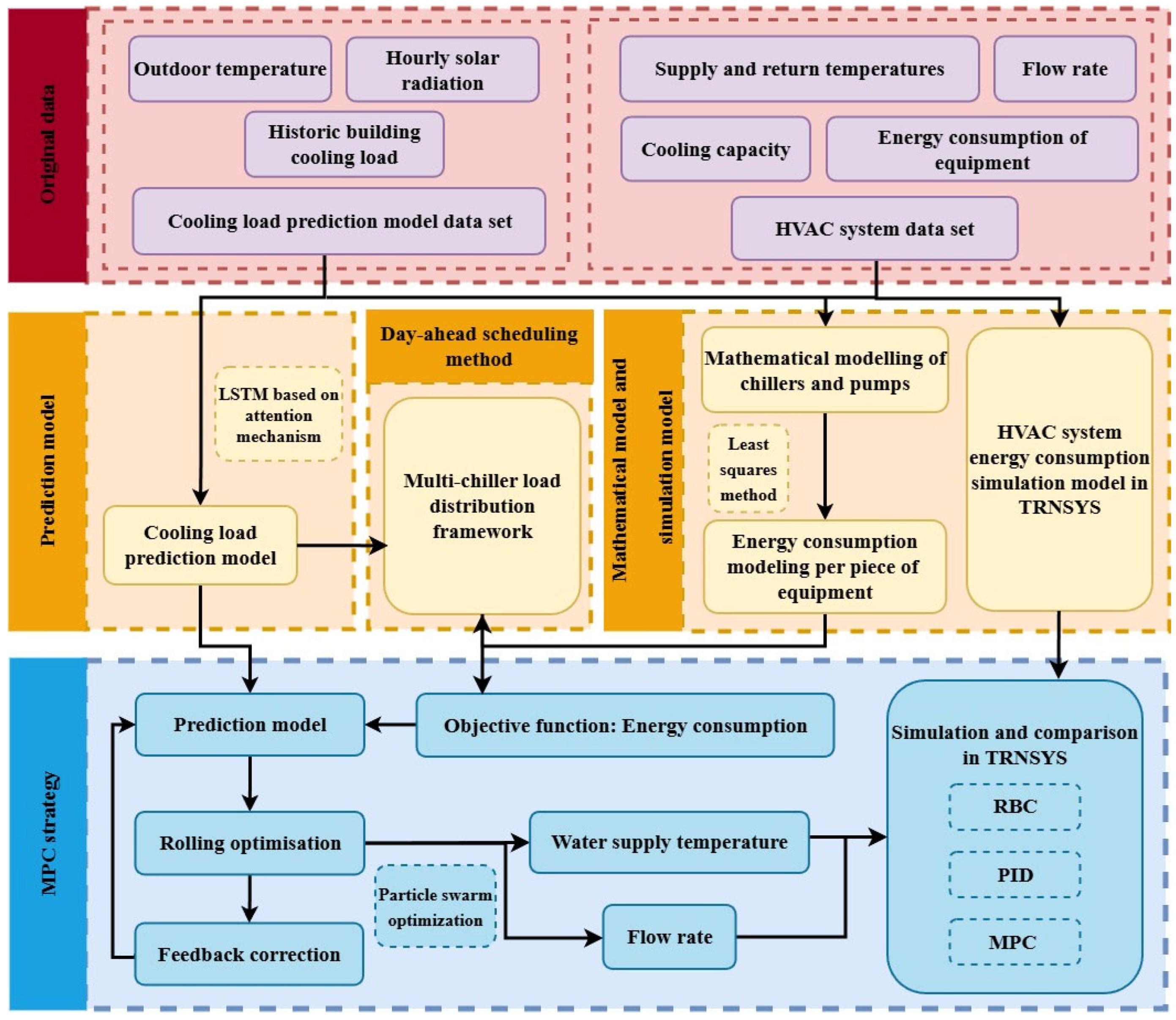

- A hierarchical control framework for HVAC systems is constructed, avoiding the complexity of mixed-integer optimization. A two-layer control framework for HVAC systems is constructed. The day-ahead scheduling method combined with MPC forms a two-layer control framework. The upper layer adopts a day-ahead scheduling strategy, using an attention mechanism-based LSTM neural network to predict building cooling load demand for the next 24 h and optimize load distribution and start–stop strategies for each chiller in advance, thus eliminating the need to use an integer optimization solver. The lower layer employs MPC for the real-time adjustment of flow rates and temperatures, treating the discrete decisions of the upper layer as given boundary conditions. This hierarchical strategy fundamentally transforms the computationally intensive MINLP problem into load scheduling-based and continuous optimization problems, thereby enabling the implementation of the optimization strategy for control purposes.

- (2)

- The PSO algorithm is adopted to perform the rolling optimization of control parameters and generate optimal control signals. The control signals are fed into the TRNSYS simulation model and compared with conventional PID control. System power consumption serves as the objective function to quantify the energy-saving effectiveness of the proposed MPC approach in HVAC systems, thereby demonstrating its superiority over conventional control methods.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. MPC Strategy for HVAC System

2.1.1. MPC Principle

2.1.2. Day-Ahead Scheduling-Based MPC Algorithm Framework

2.1.3. PSO Algorithm

2.2. Prediction Model

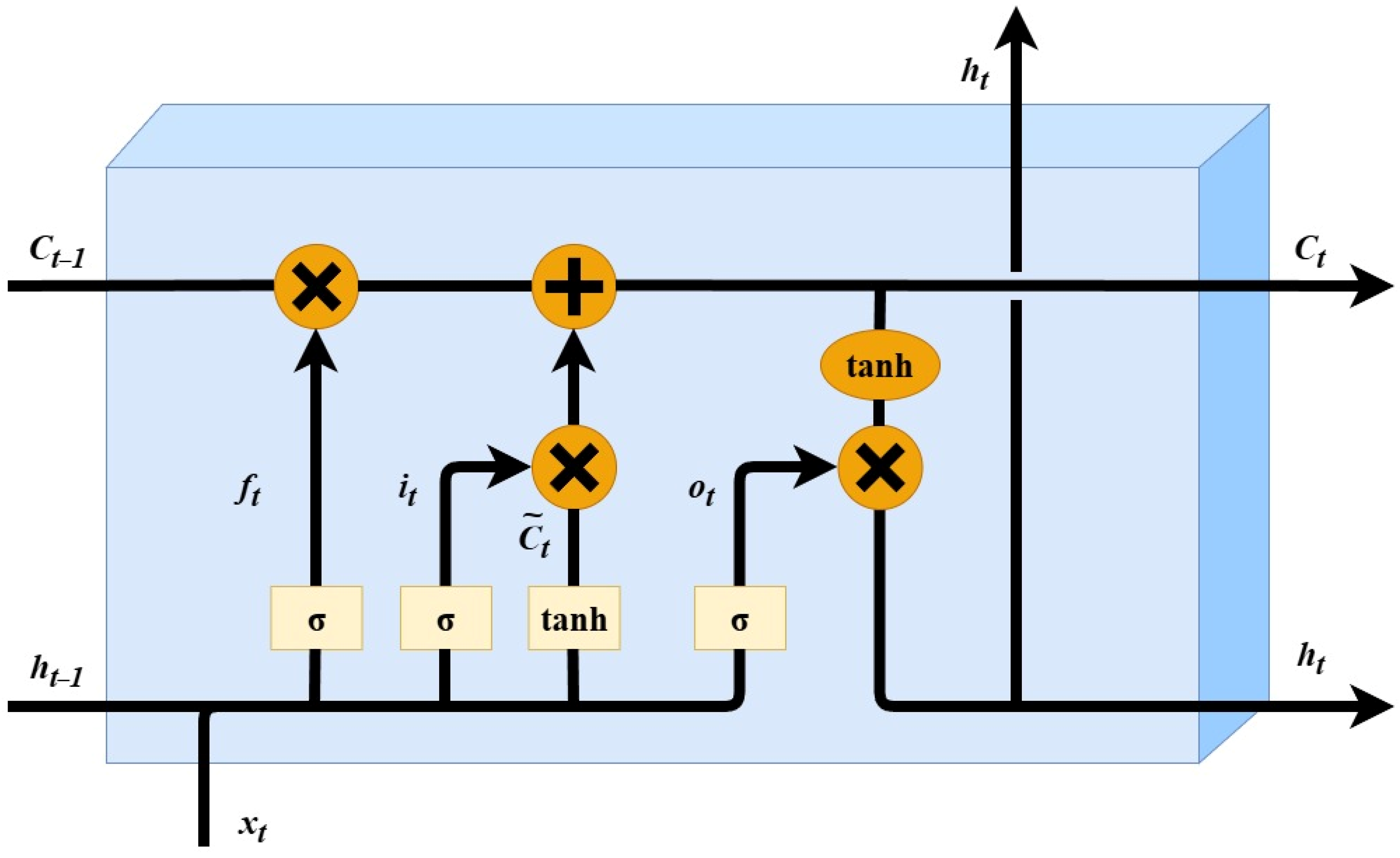

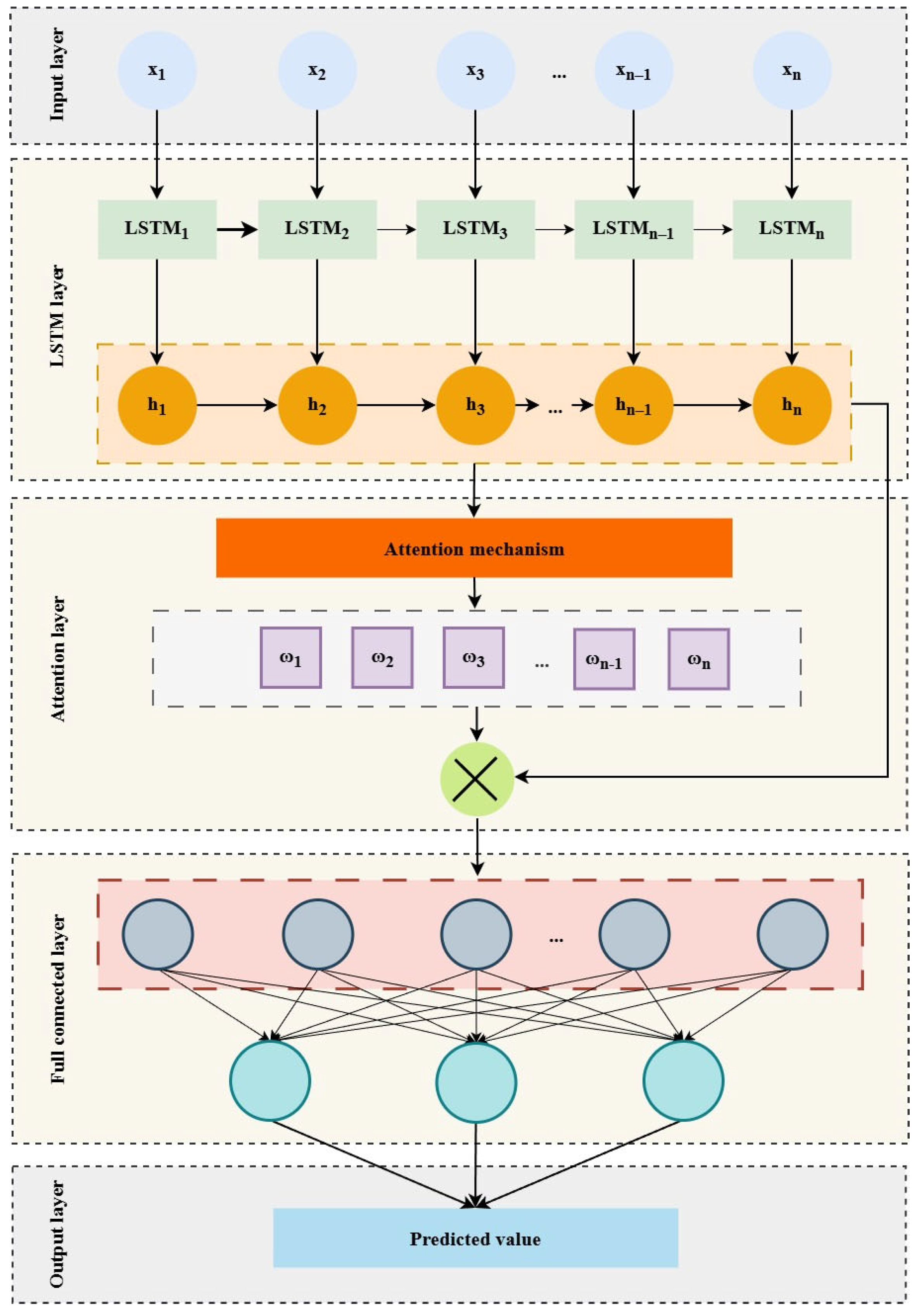

2.2.1. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)

2.2.2. Attention Mechanism

2.2.3. Attention Mechanism-Based LSTM Cooling Load Prediction Model

2.3. Evaluation Metrics

3. System Simulation

3.1. System Description

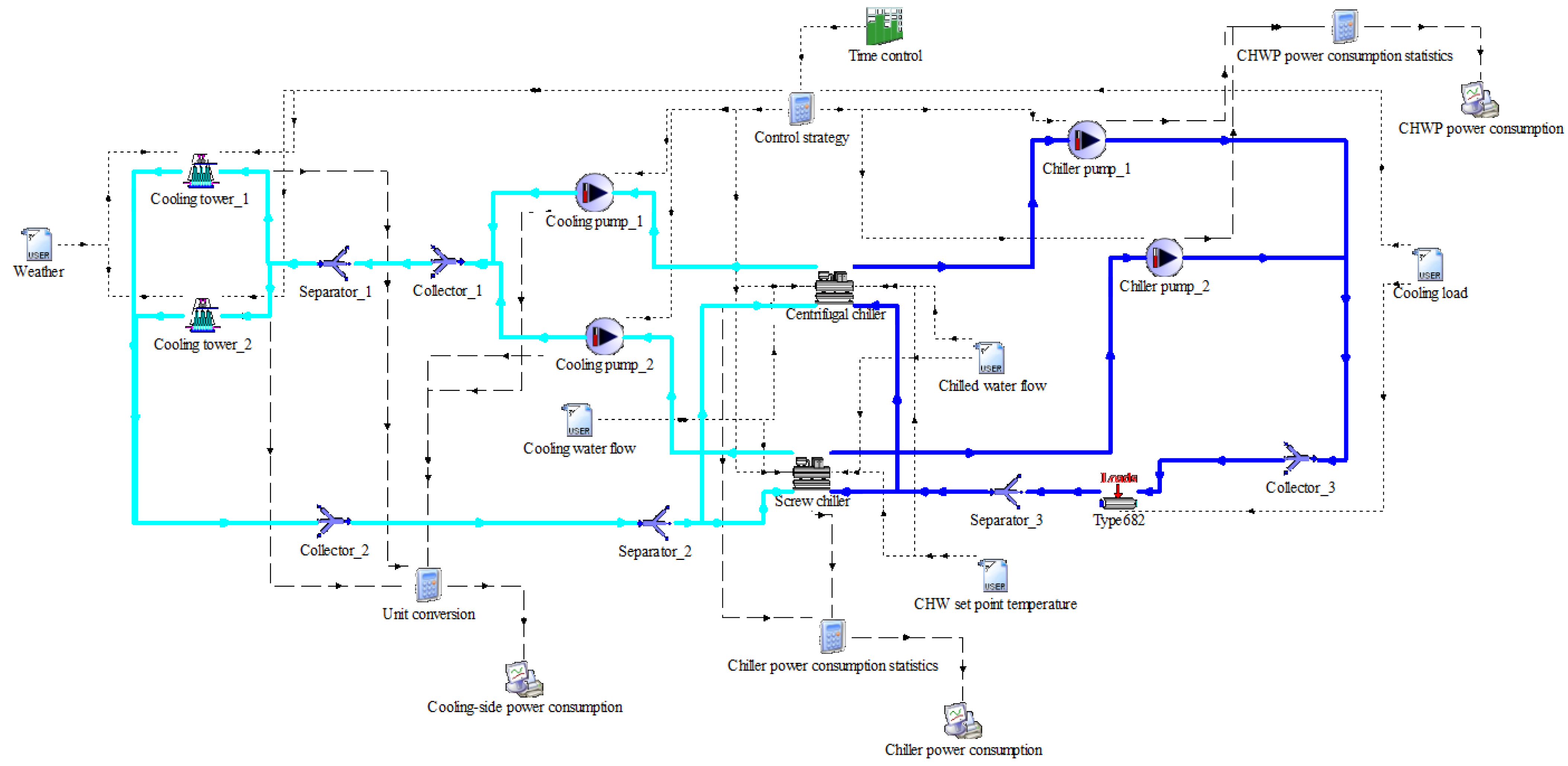

3.2. TRNSYS Simulation Model Development

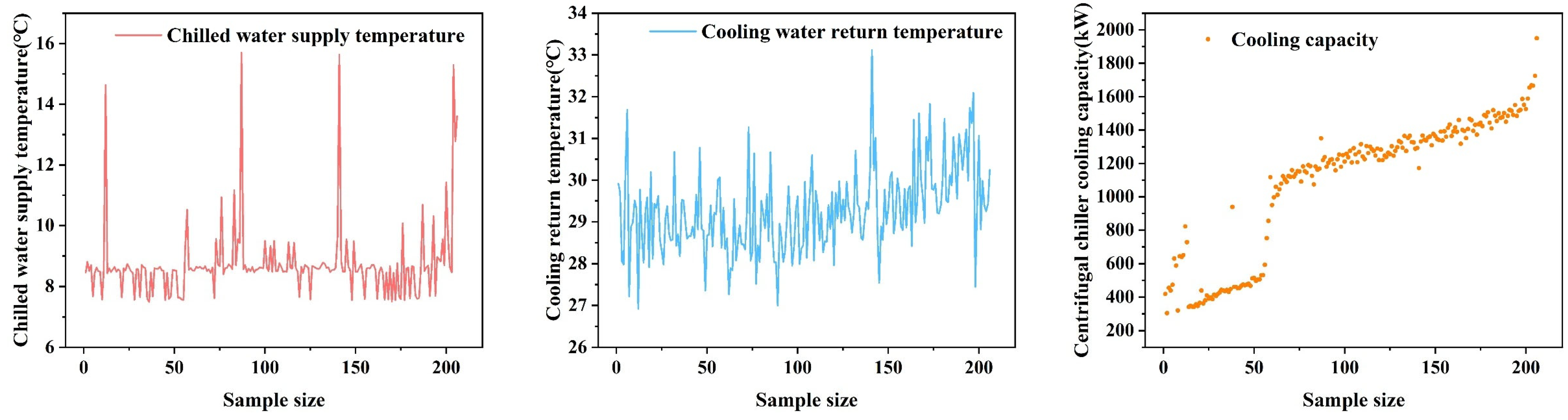

3.2.1. Input Data

Input Data Building Cooling Load Analysis

Chiller Raw Data

3.2.2. Equipment Mathematical Models

Chiller Mathematical Model

Chilled Water Pump Mathematical Model

Cooling Water Pump Mathematical Model

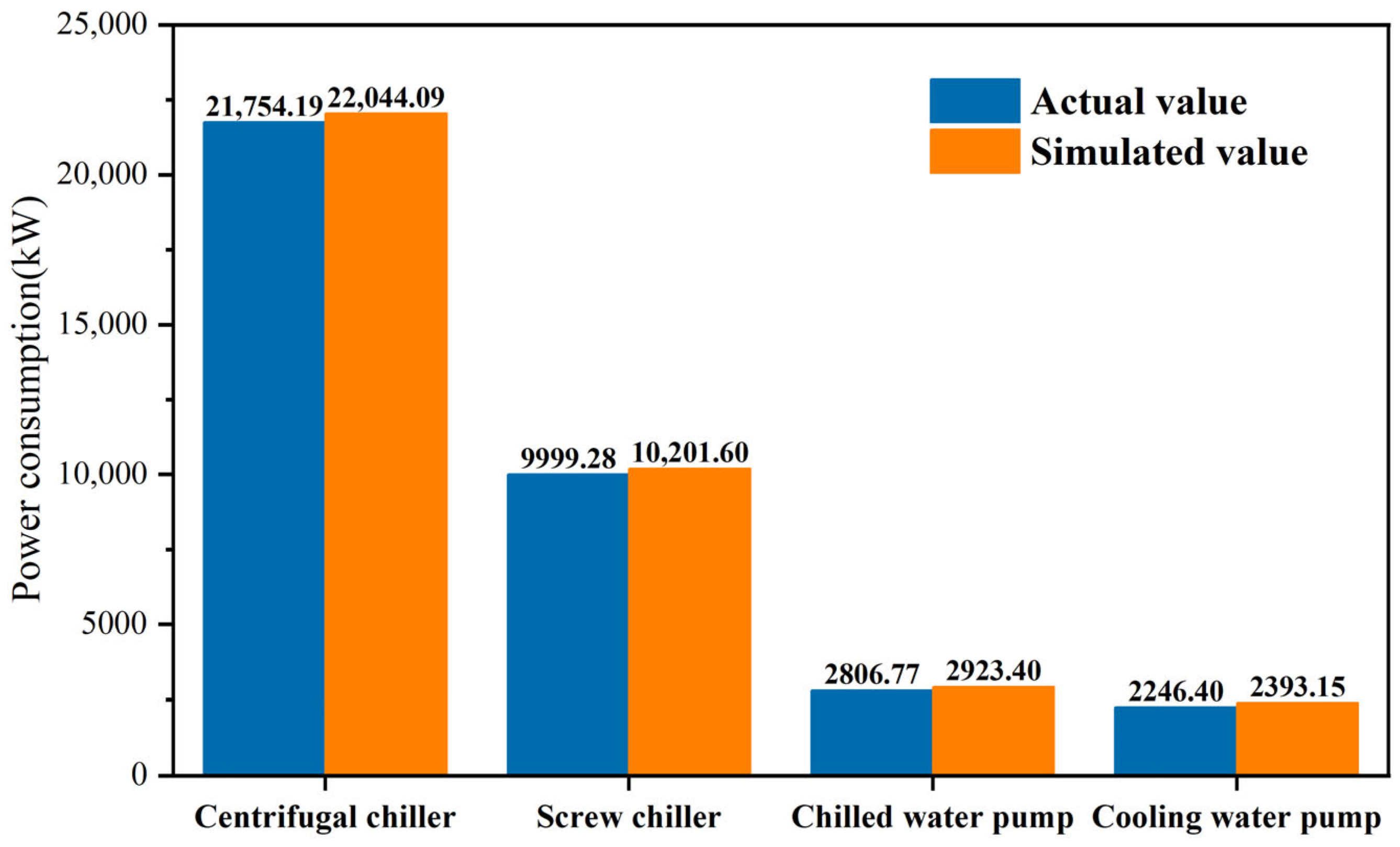

3.2.3. Simulation Model Validation

3.2.4. Prediction Model Accuracy Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Electricity Consumption Comparison

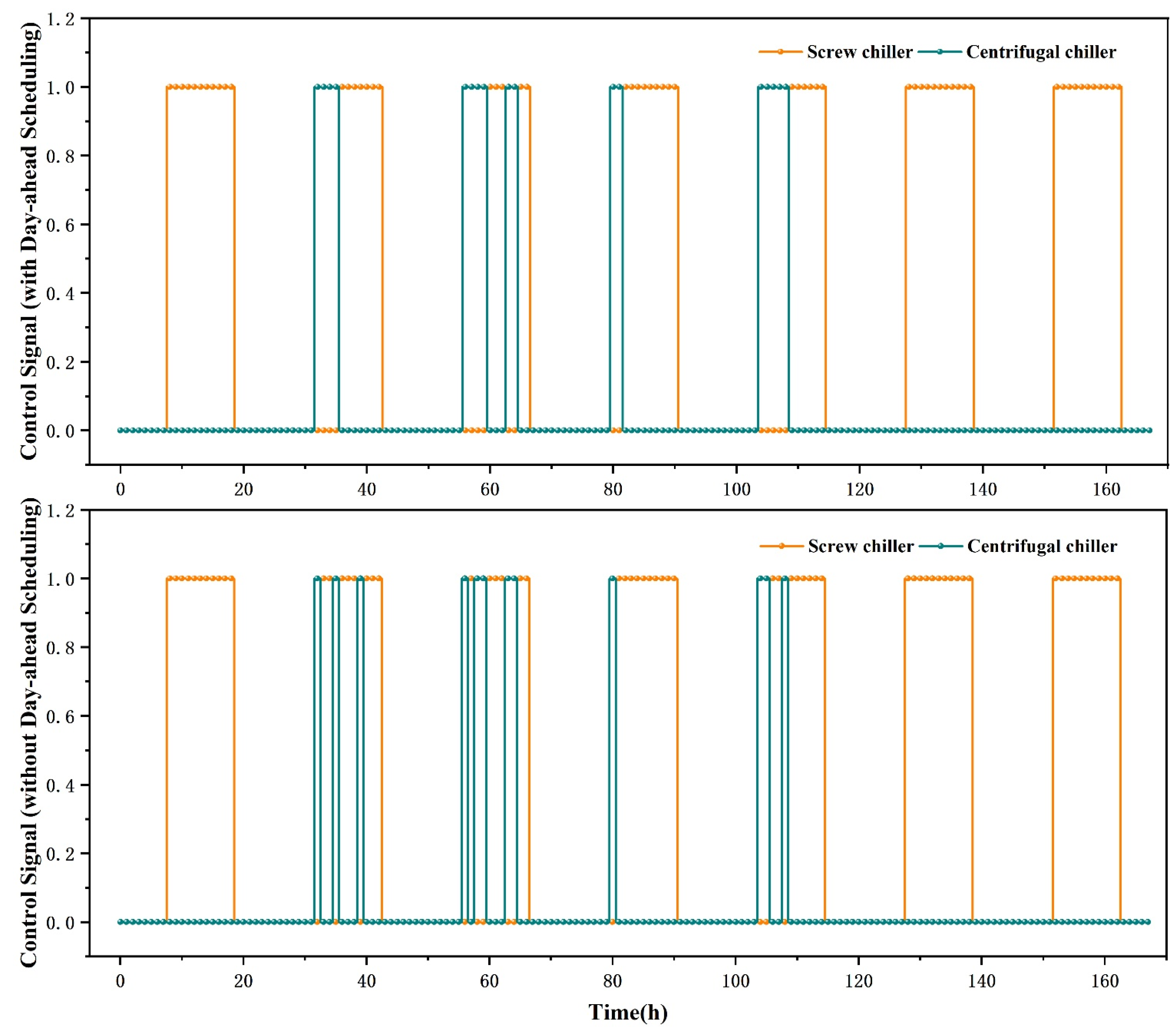

4.1.1. Equipment Start–Stop Operation

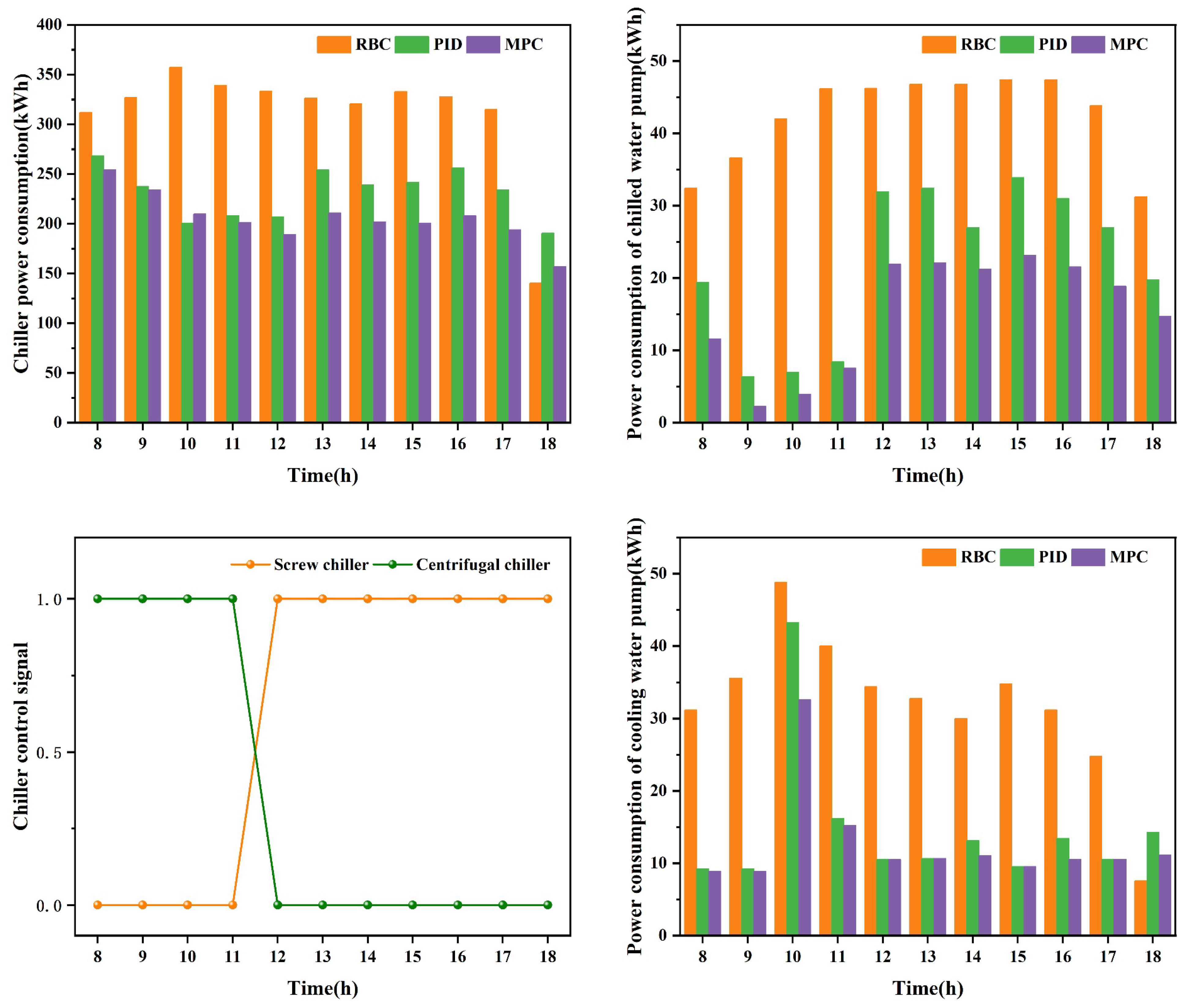

4.1.2. Daily Equipment Electricity Consumption Comparison

4.1.3. Seven-Day Power Consumption Analysis

4.2. Overall Performance Evaluation of Proposed MPC Strategy

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The LSTM neural network with an attention mechanism accurately predicts 24 h building cooling load demand. The attention mechanism automatically identifies critical time steps and input features affecting load variations, demonstrating stronger feature extraction capabilities compared to traditional LSTM models. Grid search and cross-validation optimization provide a high-precision prediction foundation for the MPC strategy.

- (2)

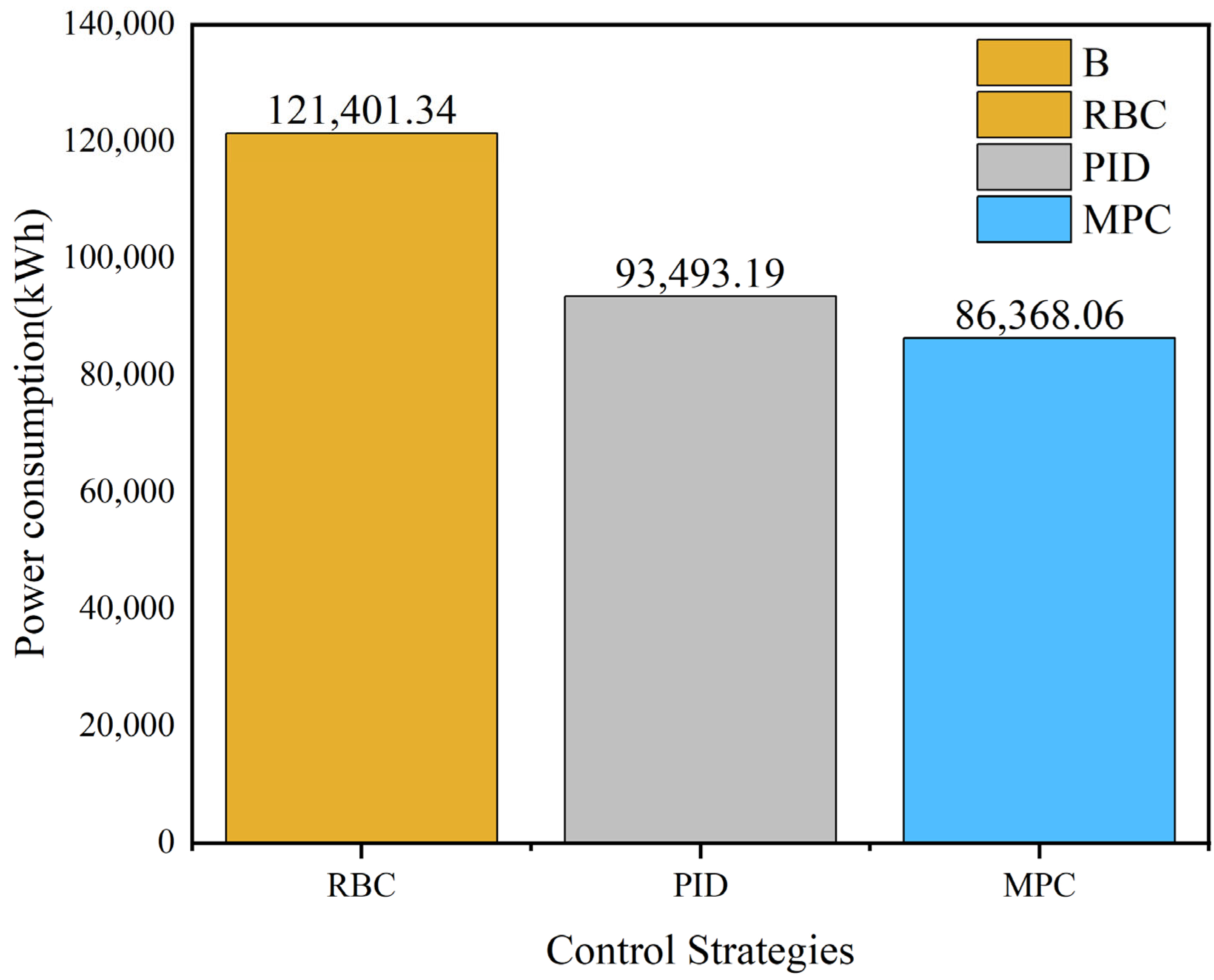

- The day-ahead MPC strategy demonstrates excellent electricity-saving performance. Weekly operation achieves 41.07% electricity savings versus traditional RBC and 9.23% versus PID control. Daily chiller electricity consumption shows 34.11% savings compared to RBC and 10.89% compared to PID control. Over a month of operation, it achieves energy savings of 8.25% compared to PID control, thereby validating the strategy’s electricity-saving potential.

- (3)

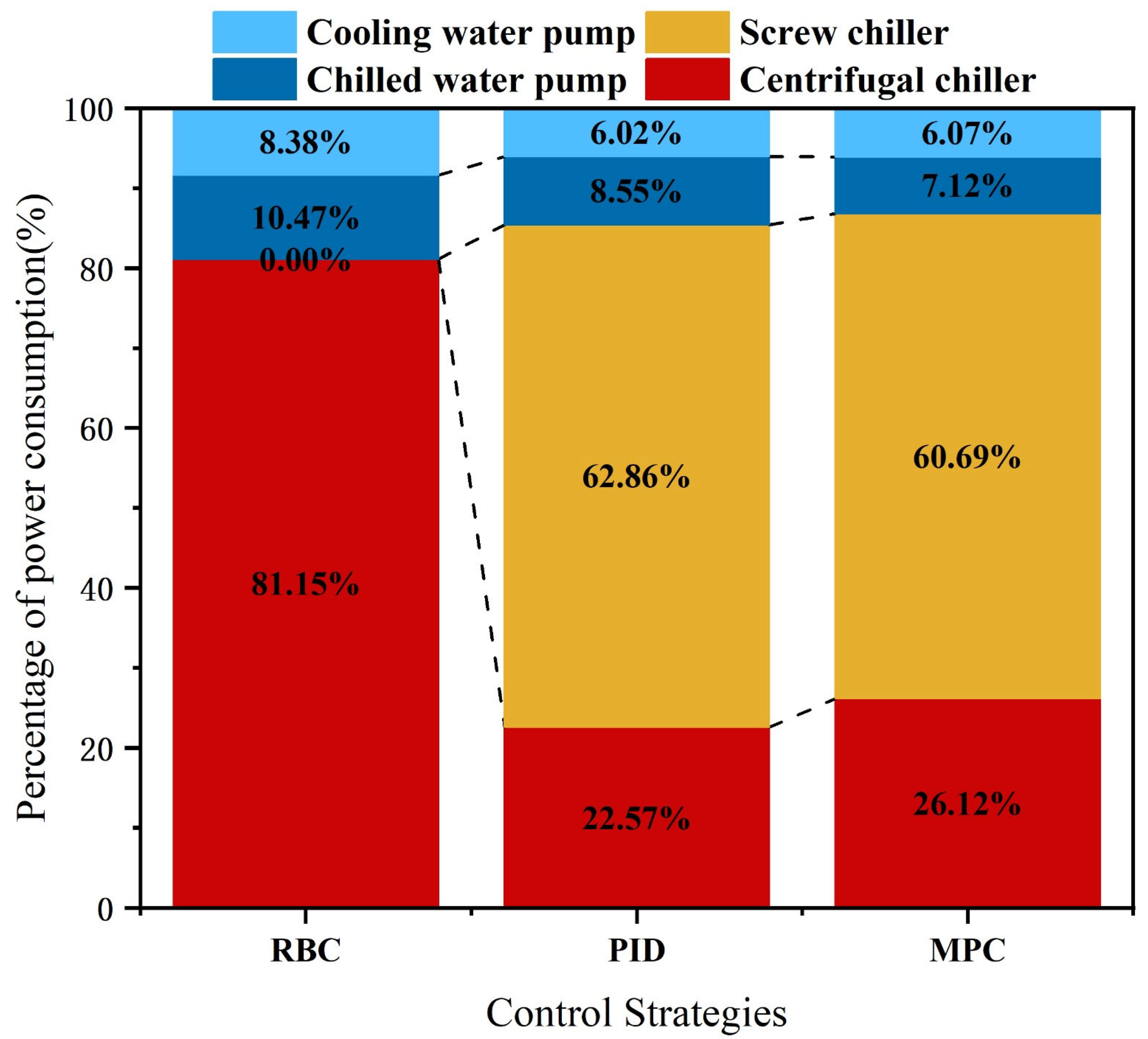

- The day-ahead MPC strategy achieves rational coordinated operation and optimal load allocation among equipment. The system switches equipment based on load variations, with an electricity consumption of 60.69% for screw chillers and 26.12% for centrifugal chillers. Compared to RBC’s single dominant mode with 81.15% centrifugal chiller usage, the equipment configuration is more balanced and efficient.

- (4)

- The MPC strategy maintains excellent electricity-saving effects and system stability under different operating conditions. Electricity-saving rates reach 35–40% on weekdays and 60% on weekends. MPC adapts to load variations while maintaining stable performance, providing technical feasibility validation for practical engineering applications.

- (5)

- Future work can focus on integrating other deep learning algorithms to improve load prediction accuracy, particularly under abnormal operating conditions and extreme weather events; incorporating explicit temporal features (such as hour of day, day of week, and day type) into the LSTM model to enhance prediction accuracy for atypical days including holidays and special events; developing adaptive MPC algorithms to enhance robustness against model uncertainties and external disturbances; and extending research to energy storage systems, heat pump systems, and hybrid energy systems to evaluate MPC strategy applicability. Due to the lack of measured data on an indoor thermal comfort environment in this study, thermal comfort indicators could not be incorporated into the current MPC framework. Future research will consider installing indoor environmental monitoring equipment and integrating thermal comfort metrics into the optimization objective function to achieve the synergistic optimization of power consumption and thermal comfort.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations and Symbols

| Attention-LSTM | attention-based long short-term memory |

| HVAC | heating, ventilation, and air conditioning |

| MAPE | mean absolute percentage error, % |

| MPC | model predictive control |

| PID | proportional–integral–derivative |

| PSO | particle swarm optimization |

| RBC | rule-based control |

| RMSE | root mean square error |

| R2 | coefficient of determination |

| chilled water supply temperature, °C | |

| chilled water return temperature, °C | |

| chilled water flow rate, m3/h | |

| cooling water supply temperature, °C | |

| cooling water return temperature, °C | |

| cooling water flow rate, m3/h | |

| chiller cooling capacity, kW | |

| building cooling load, kW | |

| outdoor temperature, °C | |

| solar radiation intensity, W/m2 | |

| power consumption of chiller, kWh | |

| power consumption of centrifugal chiller, kWh | |

| power consumption of screw chiller, kWh | |

| power consumption of chilled water pump 1 rated at 75 kW, kWh | |

| power consumption of chilled water pump 2 rated at 37 kW, kWh | |

| power consumption of cooling water pump 1 at 55 kW, kWh | |

| power consumption of cooling water pump 2 at 30 kW, kWh | |

| power consumption of cooling tower, kWh | |

| specific heat capacity, kJ/(kg·K) | |

| density, kg/m3 |

References

- Fan, C.; Xiao, F.; Li, Z.; Wang, J. Unsupervised Data Analytics in Mining Big Building Operational Data for Energy Efficiency Enhancement: A Review. Energy Build. 2018, 159, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Rysanek, A.; Nagy, Z.; Schlüter, A. Using Machine Learning Techniques for Occupancy-Prediction-Based Cooling Control in Office Buildings. Appl. Energy 2018, 211, 1343–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, K.; Wang, S.; Gao, D.; Xiao, F. Development and Validation of an Effective and Robust Chiller Sequence Control Strategy Using Data-Driven Models. Autom. Constr. 2016, 65, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Huang, G. A Hybrid Predictive Sequencing Control for Multi-Chiller Plant with Considerations of Indoor Environment Control, Energy Conservation and Economical Operation Cost. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 49, 101616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Qiang, W.; Peng, C.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, H. Research on Systematic Analysis and Optimization Method for Chillers Based on Model Predictive Control: A Case Study. Energy Build. 2023, 285, 112916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afram, A.; Janabi-Sharifi, F.; Fung, A.S.; Raahemifar, K. Artificial Neural Network (ANN) Based Model Predictive Control (MPC) and Optimization of HVAC Systems: A State of the Art Review and Case Study of a Residential HVAC System. Energy Build. 2017, 141, 96–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, S.; Xiao, F. Development and Validation of a Simplified Online Cooling Load Prediction Strategy for a Super High-Rise Building in Hong Kong. Energy Convers. Manag. 2013, 68, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amasyali, K.; El-Gohary, N.M. A Review of Data-Driven Building Energy Consumption Prediction Studies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 1192–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaghefi, A.; Jafari, M.A.; Bisse, E.; Lu, Y.; Brouwer, J. Modeling and Forecasting of Cooling and Electricity Load Demand. Appl. Energy 2014, 136, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Magoulès, F. A Review on the Prediction of Building Energy Consumption. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 3586–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotou, D.K.; Dounis, A.I. Comparison of Hospital Building’s Energy Consumption Prediction Using Artificial Neural Networks, ANFIS, and LSTM Network. Energies 2022, 15, 6453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Xie, H.; Zhu, Z.; Ji, R. Predicting Energy Consumption of Chiller Plant Using WOA-BiLSTM Hybrid Prediction Model: A Case Study for a Hospital Building. Energy Build. 2023, 300, 113642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Lei, L. A Hybrid Model for Real-Time Cooling Load Prediction and Terminal Control Optimization in Multi-Zone Buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 104, 112120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Feng, F.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z.; Li, Z. Stochastic Optimized Chiller Operation Strategy Based on Multi-Objective Optimization Considering Measurement Uncertainty. Energy Build. 2019, 195, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Wang, Q.; Kong, X.; Yang, K. Multi-Objective Optimisation Approach for Campus Energy Plant Operation Based on Building Heating Load Scenarios. Appl. Energy 2019, 250, 1600–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ding, Z.; Tang, R.; Chen, Y.; Fan, C.; Wang, J. A Machine Learning-Based Control Strategy for Improved Performance of HVAC Systems in Providing Large Capacity of Frequency Regulation Service. Appl. Energy 2022, 326, 119962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turley, C.; Jacoby, M.; Pavlak, G.; Henze, G. Development and Evaluation of Occupancy-Aware HVAC Control for Residential Building Energy Efficiency and Occupant Comfort. Energies 2020, 13, 5396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Ding, P.; Zhou, G.; Zhou, X.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Wu, H.; Fan, C.; Li, J. A Novel Machine Learning-Based Model Predictive Control Framework for Improving the Energy Efficiency of Air-Conditioning Systems. Energy Build. 2023, 294, 113258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afram, A.; Janabi-Sharifi, F. Theory and Applications of HVAC Control Systems—A Review of Model Predictive Control (MPC). Build. Environ. 2014, 72, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrooz, F.; Mariun, N.; Marhaban, M.H.; Mohd Radzi, M.A.; Ramli, A.R. Review of Control Techniques for HVAC Systems—Nonlinearity Approaches Based on Fuzzy Cognitive Maps. Energies 2018, 11, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Lee, J.; Do, S.; Mago, P.J.; Lee, K.H.; Cho, H. Energy Modeling and Model Predictive Control for HVAC in Buildings: A Review of Current Research Trends. Energies 2022, 15, 7231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wan, M.P.; Chen, W.; Ng, B.F.; Dubey, S. Model Predictive Control with Adaptive Machine-Learning-Based Model for Building Energy Efficiency and Comfort Optimization. Appl. Energy 2020, 271, 115147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinde, V.; Woldekidan, K. Model Predictive Control for Optimal Dispatch of Chillers and Thermal Energy Storage Tank in Airports. Energy Build. 2024, 311, 114120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, D. A Model Predictive Control for a Multi-Chiller System in Data Center Considering Whole System Energy Conservation. Energy Build. 2024, 324, 114919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Wang, Z.; Brugger, J.; Blum, D.; Wetter, M.; Hong, T.; Piette, M.A. Site Demonstration and Performance Evaluation of MPC for a Large Chiller Plant with TES for Renewable Energy Integration and Grid Decarbonization. Appl. Energy 2022, 321, 119343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, D.; Wang, Z.; Weyandt, C.; Kim, D.; Wetter, M.; Hong, T.; Piette, M.A. Field Demonstration and Implementation Analysis of Model Predictive Control in an Office HVAC System. Appl. Energy 2022, 318, 119104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, F.; De Masi, R.F.; Festa, V.; Mauro, G.M.; Vanoli, G.P. Optimizing Space Cooling of a Nearly Zero Energy Building via Model Predictive Control: Energy Cost vs. Comfort. Energy Build. 2023, 278, 112664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, Q.; Pan, C.; Cao, F. Energy-Efficient Operation of a Complete Chiller-Air Handing Unit System via Model Predictive Control. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 201, 117809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallianos, C.; Candanedo, J.; Athienitis, A. Application of a Large Smart Thermostat Dataset for Model Calibration and Model Predictive Control Implementation in the Residential Sector. Energy 2023, 278, 127839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Sun, Y.; Li, S.; Lu, Y.; Brouwer, J.; Mehta, P.G.; Zhou, M.; Chakraborty, A. Model Predictive Control of Central Chiller Plant With Thermal Energy Storage Via Dynamic Programming and Mixed-Integer Linear Programming. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2015, 12, 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Wenzel, M.J.; ElBsat, M.N.; Risbeck, M.J.; Drees, K.H.; Zavala, V.M. Dual Dynamic Programming for Multi-Scale Mixed-Integer MPC. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2021, 148, 107265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, S.; Mohebi, P.; Wang, D.; Ma, M.N.H.; Liu, G.; Wang, Z. Field Demonstration of Model Predictive Control for Chiller Sequencing in Large-Scale Commercial Buildings. Energy Build. 2025, 344, 116021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risbeck, M.J.; Rawlings, J.B. Economic Model Predictive Control for Time-Varying Cost and Peak Demand Charge Optimization. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2020, 65, 2957–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bonyadi, N.; Papakyriakou, A.; Lee, B. A Hierarchical Decomposition Approach for Multi-Level Building Design Optimization. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 103272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Qin, Y.; Liu, D.; Wu, X.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, X.; Wu, Y. A Model Predictive Control Strategy of Global Optimal Dispatch for a Combined Solar and Air Source Heat Pump Heating System. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 258, 124778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, X.; Ma, Z.; Sethuvenkatraman, S.; Li, W. Online Learning-Enhanced Data-Driven Model Predictive Control for Optimizing HVAC Energy Consumption, Indoor Air Quality and Thermal Comfort. Appl. Energy 2025, 383, 125341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Chen, J.; Zhao, Y.; Xi, H.; Xiao, Y.; An, D. MPC-Driven Building Energy Management for Privacy and Zero-Carbon Trade-off Optimization Using Energy Storage as Physical Noise. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 109, 113049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, J. Multi-Regional Building Energy Efficiency Intelligent Regulation Strategy Based on Multi-Objective Optimization and Model Predictive Control. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 349, 131264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saneep, K.; Sundareswaran, K.; Srinivasa Rao Nayak, P.; Puthusserry, G.V. State of Charge Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries Using PSO Optimized Random Forest Algorithm and Performance Analysis. J. Energy Storage 2025, 114, 115879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Yu, J.; Zhao, A.; Hu, Q.; Yang, S. Optimal Chiller Loading by Improved Parallel Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm for Reducing Energy Consumption. Int. J. Refrig. 2022, 136, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardakani, A.J.; Ardakani, F.F.; Hosseinian, S.H. A Novel Approach for Optimal Chiller Loading Using Particle Swarm Optimization. Energy Build. 2008, 40, 2177–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghi, A.; Cecchinato, L.; Cosi, G.; Rampazzo, M. A PSO-Based Algorithm for Optimal Multiple Chiller Systems Operation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2012, 32, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-S.; Lin, L.-C. Optimal Chiller Loading by Particle Swarm Algorithm for Reducing Energy Consumption. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2009, 29, 1730–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EL-Qasery, M.; Abbou, A.; Laamim, M.; Id-Khajine, L.; Rochd, A. Comparative Analysis of GA and PSO Algorithms for Optimal Cost Management in On-Grid Microgrid Energy Systems with PV-Battery Integration. Glob. Energy Interconnect. 2025, 8, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Si, X.; Hu, C.; Zhang, J. A Review of Recurrent Neural Networks: LSTM Cells and Network Architectures. Neural Comput. 2019, 31, 1235–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, I.; Tripathi, B.K.; Singh, A. Attention-Based LSTM Network-Assisted Time Series Forecasting Models for Petroleum Production. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 123, 106440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahdanau, D.; Chorowski, J.; Serdyuk, D.; Brakel, P.; Bengio, Y. End-to-End Attention-Based Large Vocabulary Speech Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Shanghai, China, 20–25 March 2016; pp. 4945–4949. [Google Scholar]

- Khayat, A.; Kissaoui, M.; Bahatti, L.; Raihani, A.; Errakkas, K.; Atifi, Y. Efficient Day-Ahead Energy Forecasting for Microgrids Using LSTM Optimized by Grey Wolf Algorithm. e-Prime Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2025, 13, 101054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Y. Prediction of Functional Zones Cooling Load for Shopping Mall Using Dual Attention Based LSTM: A Case Study. Int. J. Refrig. 2022, 144, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Chen, G.; Ruan, Y. Development of a Simplified Chiller Plant Calculation Tool: Architecture, Method and Verification. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 45, 103346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE. Measurement of Energy, Demand, and Water Savings. In ASHRAE Guideline 1 4-2014; ASHRAE: Peachtree Corners, GA, USA, 2014; Volume 4, pp. 1–150. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| K | Population size data | 50 |

| d | Number of iterations | 100 |

| ω | Parameters of particle swarm optimization | 0.7 |

| c1 | Learning coefficient, controls the speed at which particles move toward their individual optimal positions | 1.0 |

| c2 | Social coefficient, controls the speed at which particles move toward the global optimal position | 0.5 |

| Structure | Parameter |

|---|---|

| Hidden size | 64 |

| Num layers | 2 |

| Batch size | 32 |

| Learning rate | 0.001 |

| Dropout | 0.2 |

| Epochs | 50 |

| Model optimizer | Adam |

| Patience | 15 |

| Iterations | 200 |

| Equipment Name | Parameter | Quantity | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screw chiller | Rated cooling capacity: 1508 kW Rated power: 258 kW Refrigeration coefficient of performance: 5.85 | 1 | Fixed-frequency chiller |

| Centrifugal chiller | Rated cooling capacity: 3516 kW Rated power: 627 kW Refrigeration coefficient of performance: 5.6 | 1 | Inverter chiller |

| Chilled water pump 2 | Flow rate: 500 m3/h Power: 37 kW | 2 | Inverter pumps Two pumps, one backup |

| Chilled water pump 1 | Flow rate: 600 m3/h Power: 75 kW | 1 | |

| Cooling water pump 2 | Flow rate: 340 m3/h Power: 30 kW | 2 | Inverter pumps Two pumps, one backup |

| Cooling water pump 1 | Flow rate: 600 m3/h Power: 55 kW | 1 | |

| Cooling tower | Flow: 500 m3/h Power: 22.5 kW | 2 | Fixed-frequency cooling tower |

| a1 | a2 | a3 | a4 | a5 | a6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screw chiller | 79.7500 | −8.2072 | 0.2477 | 0.2010 | 0.000025 | 0.0008 |

| Centrifugal chiller | −41.0327 | 22.2174 | −0.5752 | 0.0435 | 0.000033 | 0.0009 |

| Training Set | Validation Set | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | RMSE | MAPE | R2 | RMSE | MAPE | |

| Centrifugal chiller | 0.9090 | 13.9 | 5.14% | 0.9061 | 10.5 | 3.90% |

| Screw chiller | 0.9844 | 6.9 | 4.54% | 0.9867 | 7.4 | 4.85% |

| Chilled water pump 1 | 0.9270 | 3.1 | 6.63% | 0.9383 | 2.4 | 5.00% |

| Chilled water pump 2 | 0.9130 | 3.2 | 6.87% | 0.9036 | 3.5 | 7.43% |

| Cooling water pump 1 | 0.9044 | 3.5 | 8.97% | 0.9196 | 3.2 | 8.46% |

| Cooling water pump 2 | 0.9093 | 3.7 | 8.89% | 0.9053 | 3.4 | 8.25% |

| Equipment Name | TRNSYS Modules | Diagram |

|---|---|---|

| Chiller | Type666 |  |

| Pump | Type110 |  |

| Cooling tower | Type126 |  |

| Separator | Type647 |  |

| Collector | Type649 |  |

| Load reading | Type682 |  |

| Input | Type9e |  |

| Output | Type65a |  |

| Schedule | Type14h |  |

| Day | Centrifugal Chiller (%) | Screw Chiller (%) | Chilled Water Pumps (%) | Cooling Water Pumps (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.64 | 2.45 | 3.74 | 5.75 |

| 2 | 4.22 | 2.87 | 3.65 | 5.55 |

| 3 | 6.88 | 3.65 | 5.46 | 5.34 |

| 4 | 7.23 | 4.02 | 5.64 | 6.73 |

| 5 | 7.29 | 4.62 | 4.35 | 6.50 |

| 6 | 4.87 | 3.23 | 6.36 | 6.32 |

| 7 | 4.02 | 2.63 | 6.67 | 6.92 |

| Average | 5.45 | 3.35 | 5.12 | 6.15 |

| Day | Centrifugal Chiller (kWh) | Screw Chiller (kWh) | Chilled Water Pumps (kWh) | Cooling Water Pumps (kWh) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9.22 | 3.86 | 1.75 | 2.24 |

| 2 | 10.65 | 4.43 | 1.71 | 2.27 |

| 3 | 17.36 | 5.52 | 2.54 | 2.13 |

| 4 | 18.21 | 6.12 | 2.63 | 2.62 |

| 5 | 18.33 | 7.07 | 2.04 | 2.51 |

| 6 | 12.32 | 4.92 | 2.96 | 2.50 |

| 7 | 10.12 | 4.04 | 3.13 | 2.70 |

| Average | 13.74 | 5.15 | 2.47 | 2.42 |

| Cooling Load Prediction Model | R2 | RMSE | MAPE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training set | 96.77% | 45.35 | 4.92% |

| Test set | 95.04% | 51.12 | 5.39% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Zhou, S.; Gong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J. A Hierarchical Control Framework for HVAC Systems: Day-Ahead Scheduling and Real-Time Model Predictive Control Co-Optimization. Energies 2025, 18, 6266. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236266

Wang X, Zhou S, Gong Y, Liu Y, Liu J. A Hierarchical Control Framework for HVAC Systems: Day-Ahead Scheduling and Real-Time Model Predictive Control Co-Optimization. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6266. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236266

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xiaoqian, Shiyu Zhou, Yufei Gong, Yuting Liu, and Jiying Liu. 2025. "A Hierarchical Control Framework for HVAC Systems: Day-Ahead Scheduling and Real-Time Model Predictive Control Co-Optimization" Energies 18, no. 23: 6266. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236266

APA StyleWang, X., Zhou, S., Gong, Y., Liu, Y., & Liu, J. (2025). A Hierarchical Control Framework for HVAC Systems: Day-Ahead Scheduling and Real-Time Model Predictive Control Co-Optimization. Energies, 18(23), 6266. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236266