Abstract

An increase in the temperature of the magnetic core causes narrowing of its hysteresis loop and reduction in the saturation magnetic flux density. Therefore, at the same operating point on the magnetization characteristic, the nonlinear effect may become stronger. In the case of the inductive current transformers, this may result in change in their transformation accuracy and increased self-generation of the low-order higher harmonics to the secondary current. Consequently, the equivalent methods used to determine their values of current error and phase displacement without operating conditions resulting from the presence of the secondary current provide less reliable results, which is particularly important for inductive current transformers with high transformation accuracy requirements and may also be significant in certain borderline cases when determining its accuracy class and the value of error is close to the limit. However, ambient temperature does not affect the transformation accuracy of conventional inductive current transformers, as their internal operating temperature is solely driven by the relatively high RMS values of the rated secondary current (1 A or 5 A) and the large number of secondary winding turns evenly distributed over the magnetic core. During thermal testing of a current transducer operating in a closed-loop feedback configuration with a Hall sensor, a deterioration of its conversion accuracy was observed at high ambient temperatures. This was caused primarily by the thermal expansion of the magnetic core, which leads to a change in the dimensions of the air gap where the Hall sensor is placed, and thus also to a change in the electrical parameters of the feedback loop circuit.

1. Introduction

A high increase in the temperature of the magnetic core plays a significant role in the conversion accuracy of inductive current transducers with a Hall sensor placed within the air gap. In general, it leads to the narrowing of its hysteresis loop and a reduction in the saturation magnetic flux density [1,2,3,4]. As a result, the nonlinear effects associated with magnetic saturation may intensify [5]. In this case the decisive factor is the change in the geometric parameters of the magnetic core, which alters its reluctance and thereby the impedance of the closed-loop current transducer’s compensation circuit. In inductive current transformers (iCTs), these thermal effects can cause changes in transformation accuracy and contribute to increased self-generation of the low-order higher harmonics to the secondary current. Consequently, equivalent methods used to estimate current error and phase displacement—when tested without the actual thermal conditions produced by secondary current flow—tend to yield less reliable results. However, in conventional iCTs, ambient temperature has negligible influence on transformation accuracy. This is because their internal operating temperature is solely driven by the relatively high RMS values of the rated secondary current (typically 1 A or 5 A) and the extensive number of secondary winding turns uniformly distributed around the magnetic core. In the paper [6], temperature is identified as one of the most critical influence quantities affecting instrument transformers, with its impact particularly severe on inductive voltage transformers. The study shows that at low temperatures, both ratio error and phase displacement increase significantly, and the effect becomes more pronounced as frequency rises, especially when transformers operate under burdened conditions. ICTs are less sensitive, though measurable deviations still occur, while low-power voltage transformers display more varied responses: resin-cast and resistive-capacitive designs show moderate sensitivity, whereas capacitive types are largely unaffected. Moreover, when combined with other influence factors such as electrical burden, temperature effects can exceed the sum of individual contributions, highlighting the need to account for temperature explicitly in wideband calibration, design, and performance assessment of instrument transformers. The paper [7] focuses on the long-term accuracy of voltage transformers. It finds that both inductive and low-power voltage transformers exhibit gradual drifts in measurement accuracy over time, largely influenced by environmental factors such as temperature and humidity. Low-power voltage transformers generally maintain better long-term stability than traditional inductive types, making them more reliable for precise voltage measurements over extended periods. The study also recommends using observed patterns to develop predictive models for forecasting accuracy behavior, supporting proactive calibration and maintenance. ICTs face a unified nonlinearity problem rooted in the magnetic core’s nonlinear B–H characteristic, which makes the excitation current and flux depart from proportionality and, under real operating conditions, produces harmonic-dependent ratio error and phase displacement that linear models systematically underestimate [8]. When the primary current contains harmonics, this nonlinearity reshapes the magnetic flux-density waveform—shifting symmetry and peak values—so both fundamental and harmonic components are transformed with errors that depend on the specific distortion profile and operating point (current level, burden) [9]. Because these effects dominate the error budget well beyond nominal power-frequency tests, they become a primary barrier to meeting wideband accuracy requirements such as the IEC 61869-1 WB2 class up to 20 kHz, especially near rated currents and practical burdens where the core is driven deeper into its nonlinear region [10]. To capture this behavior faithfully, modeling and accuracy calculations must include the measured nonlinear magnetization curve rather than linearized approximations; otherwise, both current error and phase displacement are underpredicted across realistic conditions [8]. Complementing the modeling, a routine-testing methodology that targets maximum current error and maximum phase displacement under representative distorted waveforms offers a practical way to bound nonlinearity-driven inaccuracies without exhaustive frequency–harmonic sweeps, making production and conformity assessment feasible [11]. Taken together, these results imply that wideband-capable inductive CT design, specification, and verification must be organized around the core’s nonlinear magnetization, its interaction with harmonic distortion and burden, and test procedures explicitly tailored to reveal worst-case behavior [8,9,10,11]. The self-generation concept in iCTs refers to the phenomenon where low-order harmonics—such as the 3rd, 5th, or 7th—are produced in the secondary current even when the primary current is purely sinusoidal. This occurs due to the nonlinear magnetization characteristic of the CT’s magnetic core: as the core operates near the knee of its magnetization curve, variations in flux density caused by the primary current and secondary load generate harmonic components internally. These self-generated harmonics distort the secondary waveform, affecting both current magnitude and phase, which leads to measurement errors that depend on the phase angle of the harmonic components [8,9,10,11]. The compensation in iCTs is aimed at correcting the ratio and phase errors of the secondary current for higher harmonics. In paper [12], an algorithm is proposed that estimates and compensates for errors for multiple harmonics, improving the fidelity of the secondary current. In paper [13], tensor linearization to model the CT as a nonlinear system is proposed, allowing simultaneous correction of amplitude and phase errors across a wide harmonic range. In paper [14], an experimental method is presented to calibrate and adjust the iCT outputs current for each harmonic, demonstrating improved harmonic transformation accuracy without extensive redesign. In paper [15], an adaptive technique is proposed that effectively compensates for both the filtering behavior and harmonic distortion introduced by current and voltage transformers. This approach utilizes a flexible, linear-in-parameters polynomial model to address nonlinear effects at low-order harmonics. The model complexity is adjusted iteratively for each harmonic order, enhancing accuracy without overfitting. Experimental tests on inductive CTs and voltage transformers demonstrated the method’s effectiveness in improving harmonic measurement accuracy. However, these compensation methods are currently designed without considering thermal effects—particularly the amplitude of self-generated harmonics, such as the third, which tends to increase after the warm-up period of an iCT due to changes in the magnetization curve with temperature. Thus, while harmonic compensation significantly enhances their accuracy for distorted currents, additional errors caused by temperature-dependent effects remain unaddressed. This problem also concerns the change in magnetic flux density with the waveform shape caused by primary current harmonic distortion. The ampere-turns method may be used to test the transformation accuracy of window type iCTs, particularly under distorted currents. It relies on the principle that the ampere-turns—i.e., the product of current and number of turns on the single-wire primary winding—are equal to those on the additional winding if the number of turns determined results from the rated transformation ratio and the rated secondary current. In this method, high RMS current and reference transducers are not required, as the rated value of the primary current in the additional primary winding is equal to the rated secondary current [16,17,18]. The values of current error and phase displacement are determined from composite error and its phase angle in relation to the primary current in the differential measuring system [8,9,10,19].

Closed-loop current transducers with a Hall sensor exhibit a different response to changes in operating temperature. During thermal tests, as a response to significant increased ambient temperature, a deterioration in their conversion accuracy—reduced gain—was observed [20,21,22]. The article [20] discusses the fundamental technologies used for current measurement, focusing on resistive shunts and Hall-effect sensors (both open-loop and closed-loop types), along with their advantages and limitations. It explains how Hall-effect transducers work and describes the main sources of measurement errors, such as electrical offset, magnetic offset, gain error, and nonlinearity error. The paper also highlights how operating temperature influences the magnitude of these errors. Another important part of the article is the distinction between gain error values specified in datasheets and the actual behavior of transducers in real-world operating conditions including temperature effects. The authors emphasize that, in practice, some errors—such as those related to magnetic offset or gain—tend to partially cancel out during the cyclic charging and discharging of a battery. However, the electrical offset and the linearity of the transducer remain crucial factors for maintaining measurement accuracy. The article [21] compares different types of current sensors, focusing on open-loop (OL) and closed-loop (CL) designs, as well as the use of Hall elements versus magnetic probes. It explains that open-loop sensors are simpler and consume less power, but they suffer from lower accuracy, worse temperature stability, and higher noise. Closed-loop sensors, by adding a feedback loop, achieve much better accuracy, linearity, noise reduction, and bandwidth. Traditionally, CL sensors use Hall elements, but these components have significant limitations: low gain (~1 mV/A), relatively high offset (100–200 mA), and strong temperature drift. Replacing the Hall element with a magnetic probe (based on an amorphous VITROVAC strip) provides major improvements: very high gain (~500 mV/A), very low offset (<5 mA), almost zero temperature drift, and easier noise filtering due to high-frequency operation (~400 kHz). The high gain of the magnetic probe makes the influence of feedback electronics negligible, which simplifies circuit design and reduces cost. It also allows for better separation of the magnetic and electronic parts. Experimental results show that CL sensors with a magnetic probe deliver superior performance compared to CL sensors with Hall elements: better linearity (<0.7%), lower temperature drift (<0.2%), wider bandwidth (200 kHz), and faster response (<1 µs). Compared to OL Hall sensors, the advantage is even greater. Importantly, the cost of a CL magnetic-probe sensor is comparable to advanced OL sensors and lower than CL Hall-based solutions. The article [22] focuses on the modeling of closed-loop Hall-effect current sensors using a magnetic equivalent circuit. Its parameters are identified through a combination of 3D finite element method and simulations with optimization techniques. The proposed model considers both magnetic nonlinearities and dynamic effects caused by eddy currents, which are often difficult to capture in simplified analytical models. Validation carried out on several types of sensors demonstrated a high agreement between the model predictions and experimental measurements over a wide frequency range, while maintaining a low simulation error. It is worth mentioning that the fourth-generation magnetic sensing element, based on Tunnel Magnetoresistance (TMR) technology, exhibits enhanced performance characteristics, including higher sensitivity, lower power consumption, and improved thermal stability in relation to the closed-loop current transducers with a Hall sensor [23,24,25].

In this paper, thermal aspects in the operation of iCTs and active closed-loop, zero-flux transducers are analyzed. This study concerns the influence of the internal and ambient temperature. In the case of iCTs, the required warm-up time to reach thermal stability was determined based on the absence of changes greater than one degree Celsius in the secondary winding temperature over a one-hour period during transformation accuracy testing as defined in the temperature-rise test (type tests of iCT) [26,27]. The values of current error and phase displacement were monitored over a period of two hours. In addition, the magnitude of the third harmonic generated in the secondary current was measured. Moreover, to verify the stability of the operating conditions of the tested iCT, the primary and secondary current, along with the secondary voltage, were monitored continuously during the test. In all cases, the required warm-up time for the measuring equipment and connected load was ensured through prior testing of the transformation accuracy using the same type of iCT. During this study, both standard measurement setups typically used to evaluate the transformation accuracy of iCTs were applied: the ampere-turns method (used when an additional primary winding could be implemented) and the reference iCT method. In all cases, a digital power meter and a current comparator were used to perform measurements. A climate chamber was used to simulate environmental extremes by setting limiting conditions such as maximum temperature of +50 °C and an intermediate value of +10 °C with humidity levels from 10% to 90% (with 10% steps) and a minimum temperature of −25 °C for evaluation of iCTs performance for various ambient conditions (tests with the ampere-turns method). Moreover, a freezer was used to force their ambient temperature to −25 °C during the accuracy tests with the reference iCT for a single primary conductor. To assess the influence of temperature on the operation of the zero-flux transducer, the secondary current was measured at a reference value of the primary current supplied by a programmable power source. The relative error of converting the primary current into the secondary current referenced to the stabilized operating temperature inside the transducer housing under nominal ambient conditions was then determined. The test signals were sinusoidal and distorted (with a 30% level of the third harmonic) currents of frequency from 50 Hz to 10 kHz (30 kHz third harmonic). The ambient temperature of the tested transducer was controlled using a BINDER MKF 115 climatic chamber, which in this case was used for testing in the range from +20 °C to 150 °C.

The results confirmed the statement provided in the standard IEC 61869-2 that iCT accuracy performance is independent from the external operating conditions [27]. However, it is shown that the internal thermal effect may be present, as the secondary current magnitude is responsible for the temperature of the magnetic core and secondary winding wire. The change in transformation accuracy during the 2 h test is observed in the case of several tested iCTs. The importance of such variation depends mainly on the required transformation accuracy of the unit under evaluation and is significant in certain borderline cases when determining its accuracy class and the value of error is close to the limit. Moreover, in the case of some iCTs, the rise in internal temperature caused by the secondary current after the warm-up period may also lead to a noticeably increased self-generation of the third harmonic in the secondary current. Under elevated operating temperature conditions, the additional gain error can significantly degrade the performance of the closed-loop current transducers with a Hall sensor, and it may even exceed the permissible value of the gain error declared by the manufacturer. The main source of this deterioration is geometric change in dimensions of the magnetic core and air gap, which leads to change in its resultant magnetization characteristic.

2. Long-Term Evaluation of the Transformation Accuracy of Inductive Current Transformers with Assessment of the Influence of the Ambient Temperature

During the laboratory studies, 18 iCTs were tested. However, the results for 6 units were selected for presentation due to their representativeness and clarity. The selected window-type iCTs are as follows:

- Model A—250 A/5 A (designed as reference source, in-house produced);

- Model B—500 A/5 A (class 0.2; 2.5 VA produced by manufacturer 1);

- Model C—400 A/1 A (class 0.2S; 5 VA; in-house produced);

- Model D—250 A/1 A (class 0.5; 2.5 VA produced by manufacturer 2);

- Model E—300 A/1 A (class 0.2; 2.5 VA produced by manufacturer 1);

- Model F—400 A/1 A (class 0.5S, 2.5 VA produced by manufacturer 2).

The measuring systems were powered by a custom signal source consisting of an audio power amplifier and an arbitrary waveform generator. This setup provides a pure sinusoidal power supply.

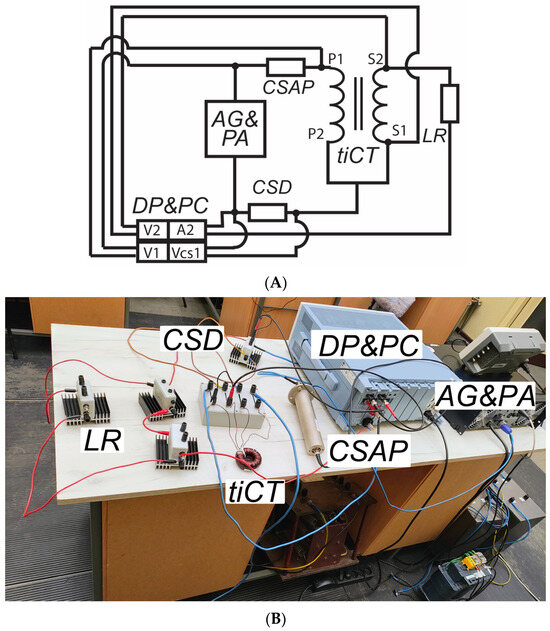

In Figure 1, the developed measuring system for evaluation of the transformation accuracy and thermal stability of iCT in ampere-turns condition is presented.

Figure 1.

Developed measuring system for evaluation of the transformation accuracy and thermal stability of iCT in ampere-turns condition: (A) electrical diagram, (B) photo.

In Figure 1A,B, the following abbreviations are used:

AG and PA—arbitrary waveform generator combined with an audio power amplifier, tiCT—tested inductive current transformer, DP and PC—digital power analyzer WT 5000 with data acquisition into computer, CSD—resistive, non-inductive current shunt used to measure differential current, CSAP—resistive, non-inductive current shunt used to measure current in the auxiliary winding, LR—resistive, non-inductive current shunt used to provide a load for the secondary winding of the tiCT.

The transformation accuracy of iCT models A, B, and C was tested under rated ampere-turns conditions. To achieve this, an additional primary winding was implemented, with the number of turns determined based on the rated transformation ratio. In this case, the transformation accuracy is evaluated with respect to the current in this winding using the differential method. The differential current is obtained by connecting the additional primary winding and the secondary winding of the tested iCT in opposition. Based on the measured currents in the additional winding and in the differential connection, the composite error is then calculated. At the same time, the RMS value of the secondary current is derived using also the phase angle measured between these currents using the law of cosines. This enables calculation of the current error. Finally, using a vector diagram, the phase displacement (representing the angular component of the composite error) is determined from the distance between the primary and secondary current vectors using the Pythagorean theorem [8,9,10,11]. The climate chamber was additionally used to simulate environmental extremes by setting limiting conditions such as maximum temperature of +50 °C and an intermediate value of +10 °C with humidity levels from 10% to 90% (with a 10% step) and a minimum temperature of −25 °C for evaluation of iCTs performance for various ambient conditions.

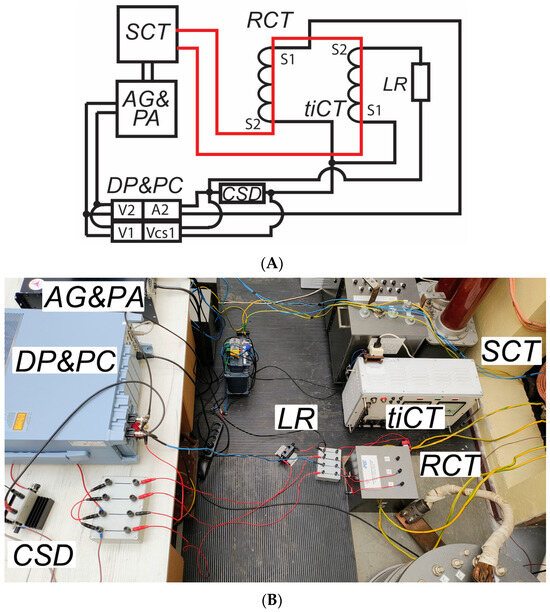

Figure 2 shows the developed measuring system used to evaluate the transformation accuracy and thermal stability of the tested iCT models D, E, and F in comparison with a reference iCT.

Figure 2.

Developed measuring system for evaluation of the transformation accuracy and thermal stability of iCT in comparison with a reference iCT: (A) electrical diagram (red line—high-current cable), (B) photo.

SCT—step-up current transformer, RCT—reference inductive current transformer.

In this case, the transformation accuracy is evaluated with respect to the secondary current of the reference inductive current transformer, whose transformation accuracy was previously evaluated in rated ampere-turns conditions. The differential method is also used, but the differential current is now obtained by connecting the secondary windings of the tested iCT and reference iCT in opposition. The procedure and used equations for calculation of current error and phase displacement are presented and described in detail in the previously published paper [8,9,10,11].

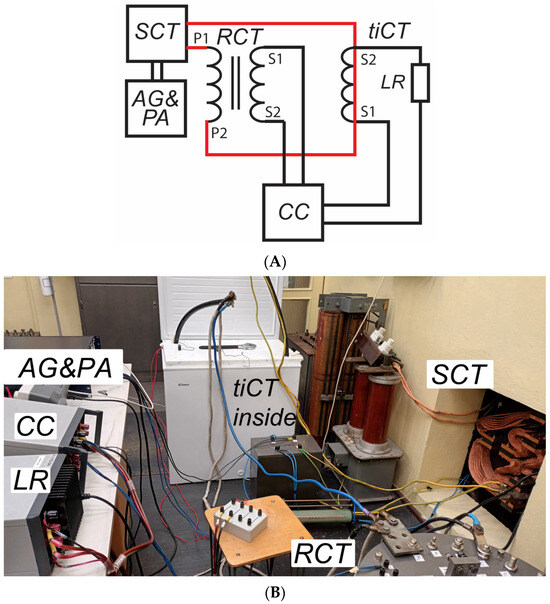

In Figure 3, the configuration of the measuring setup is presented when a current comparator is used and the tested iCT is placed inside the freezer to ensure a −25 °C ambient temperature with practically 0% level of humidity.

Figure 3.

Developed measuring system for evaluation of the transformation accuracy and thermal stability of iCT placed inside the freezer in comparison with a reference iCT: (A) electrical diagram (red line—high-current cables), (B) photo.

CC—current comparator.

The experiment was repeated using a single primary conductor, which could not be accommodated in the climatic chamber. Therefore, a freezer was used to maintain the ambient temperature at −25 °C during the accuracy measurements. In this scenario the current error and phase displacement were directly determined by the current comparator.

The thermal performance of inductive iCTs is evaluated based on their key accuracy parameters: current error and phase displacement.

The current error is defined as follows:

where I2(h) is the RMS value of the 1st or 3rd component of the secondary current of iCT and I’1(h) is the 1st or 3rd component of the primary current converted to the secondary side. The relative gain error of converting the primary current into the secondary current, referenced to the stabilized operating temperature inside the transducer housing under nominal ambient conditions, is defined as follows:

where I2(t)—RMS secondary current of the transducer at increased ambient temperature, I2(N)—RMS secondary current of the transducer at reference stabilized operating temperature (25 °C).

The phase displacement is defined as follows:

where φ2(h) is the phase angle of the 1st or 3rd component of the secondary current of iCT and φ1(h) is the phase angle of the 1st or 3rd component of the primary current.

The percentage change in the self-generated third harmonic relative to the average measured value is defined as follows:

where I2h3 is the RMS value of the 3rd component of the secondary current of iCT measured in the secondary current while iCT primary current is sinusoidal and I2h3AVG is its averaged value from all measured results for 2 h test.

To verify the stability of the operating conditions of the tested iCT the secondary winding resistive load is monitored continuously during the test as follows:

where U2h1 is the RMS value of the 1st component of the secondary voltage of iCT and I2h1 is the RMS value of the 1st component of the secondary current.

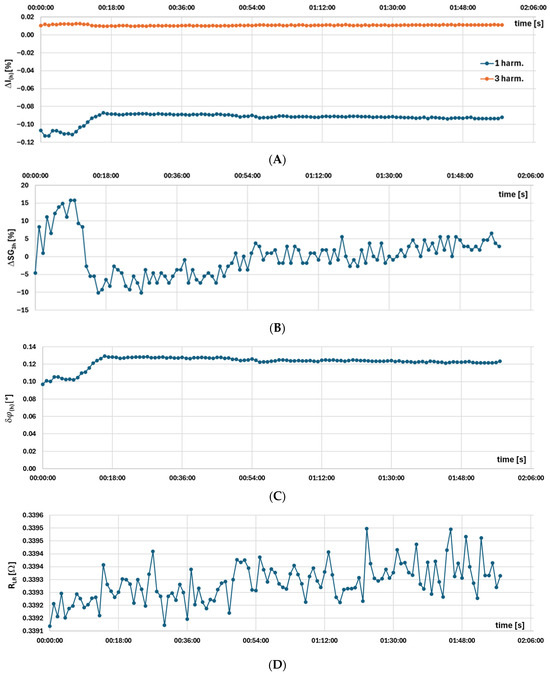

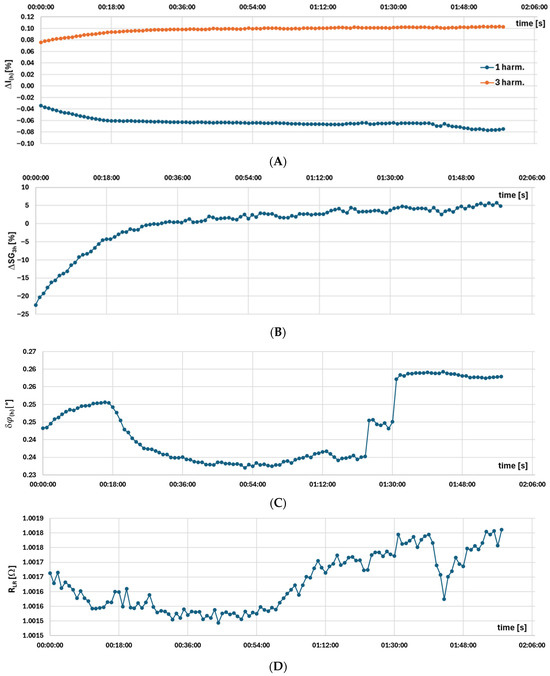

Figure 4 shows the measurement results for the model A iCT, obtained using the setup presented in Figure 1 (rated ampere-turns conditions). The parameters include (A) current error, (B) percentage change in the self-generated third harmonic relative to the average measured value, (C) phase displacement, and (D) secondary winding load.

Figure 4.

Measurement results for the model A iCT, obtained using the setup presented in Figure 1 of: (A) current error, (B) percentage change in the self-generated third harmonic relative to the average measured value, (C) phase displacement, and (D) secondary winding load.

The result from Figure 4A indicates that the change in current error in first 18 min of the test is from about −0.12% to −0.09%. In this case the developed reference iCT is improving its accuracy performance as the temperature of secondary windings increases to 35 °C. It should be noted that the secondary winding load active power is intentionally increased during this test to 8.5 W at 1 A RMS in this scenario, as in this condition the change in current error is easier to observe due to the higher value of current error. The percentage change in the self-generated third harmonic relative to the average measured value is quite high (Figure 4B), but this results only from its very small level (Figure 4A—3 harm.). The change in phase displacement is from about 0.1° to 0.13° (Figure 4C). Simultaneously, the secondary winding voltage and current are measured to control the secondary winding load, as its variation may also be responsible for changes in current error and phase displacement (Figure 4D). This test was performed for environmental extremes by setting limiting conditions of the climatic chamber, such as maximum temperature of +50 °C and an intermediate value of +10 °C with humidity levels from 10% to 90% (with a 10% step) and a minimum temperature of −25 °C. The results confirmed the statement provided in the standard IEC 61869-2 that iCT accuracy performance is independent from the external operating conditions [27]. However, the change in the transformation accuracy is observed during the 18 min warm-up time of the tested iCT.

In Figure 5, the measurement results for the model B iCT, obtained using the setup presented in Figure 1 (rated ampere-turns conditions). The parameters include the following: (A) current error, (B) percentage change in the self-generated third harmonic relative to the average measured value, and (C) phase displacement.

Figure 5.

Measurement results for the model B iCT, obtained using the setup presented in Figure 1 of: (A) current error, (B) percentage change in the self-generated third harmonic relative to the average measured value, and (C) phase displacement.

The results presented in Figure 5A indicate that the current error changes from approximately −0.14% to −0.12% during the first 36 min of the test. In this case, the manufactured iCT shows an improvement in accuracy over time. The active power of the secondary winding load was 2.5 W, and the test was performed under conditions simulating the rated primary current: 5 A RMS, using 100 turns in the additional primary winding. The percentage change in the self-generated third harmonic relative to the average measured value is relatively low (Figure 5B), which is due to its relatively high base amplitude (see Figure 5A, third harmonic). The variation in phase displacement is marginal (Figure 5C). Overall, as with the previously tested iCT, no warmup time is required to achieve thermal stability in this case.

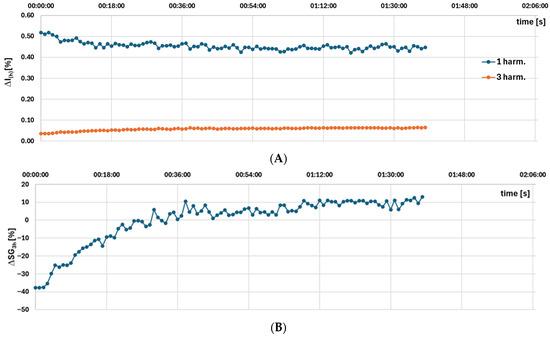

Figure 6 presents the measurement results for the model C iCT, obtained using the setup shown in Figure 1 under rated ampere-turns conditions. The evaluated parameters include the following: (A) current error, and (B) percentage change in the self-generated third harmonic relative to the average measured value.

Figure 6.

Measurement results for the model C iCT, obtained using the setup presented in Figure 1 of: (A) current error and (B) percentage change in the self-generated third harmonic relative to the average measured value.

The results presented in Figure 6A indicate no significant change in the current error values (1 harm). However, this developed iCT shows a noticeable increase in the self-generated higher harmonics during the first 54 min of the test (Figure 6A—3 harm.). The percentage change in the self-generated third harmonic relative to the average measured value is also high (Figure 6B), which is due to its relatively low amplitude. The diameter of the secondary winding of this iCT is 0.45 mm, and the current density is 6 A/mm2. The temperature of secondary windings increases to 80 °C.

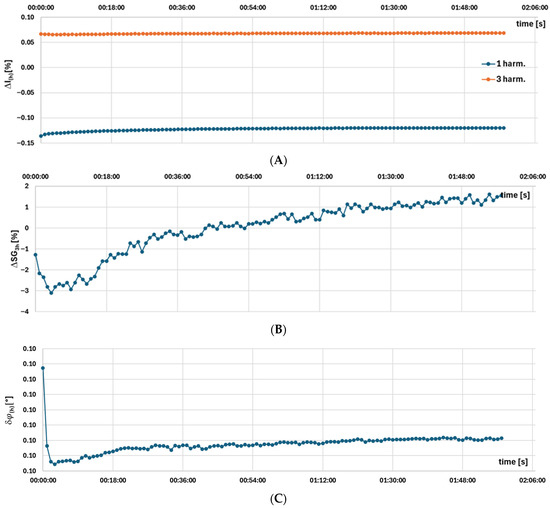

Figure 7 shows the measurement results for the model D iCT, obtained using the setup presented in Figure 2 (test with the single primary conductor at rated exploitation conditions). The parameters include the following: (A) current error, (B) percentage change in the self-generated third harmonic relative to the average measured value, (C) phase displacement, and (D) secondary winding load.

Figure 7.

Measurement results for the model D iCT, obtained using the setup presented in Figure 2 of: (A) current error, (B) percentage change in the self-generated third harmonic relative to the average measured value, (C) phase displacement, and (D) secondary winding load.

The result from Figure 7A indicates that the change in current error is from about −0.03% to −0.08% for the 2 h test. In this case, model D of iCT 250 A/1 A (class 0.5, 2.5 VA produced by manufacturer 2) is deteriorating its accuracy performance as the temperature of secondary windings increases to 85 °C. It should be noted that the secondary winding load active power is intentionally reduced during this test to 1 W at 1 A RMS rated secondary current. This action is intended to assess also the influence of the secondary winding load on the thermal stability and warm-up time of iCT. It was observed that the percentage range of changes in the current error percentage value is the same, but in the case of its higher value, typically at higher secondary winding load, the absolute change is greater and more easily visible. The percentage change in the self-generated third harmonic relative to the average measured value is quite high (Figure 7B) and it concerns a particularly high percentage value of potential current error for a 3rd higher harmonic equal to 10% of the main component of transformed distorted current (Figure 7A—3 harm.). The change in phase displacement is between about 0.23° and 0.26° (Figure 7C). Simultaneously, the secondary winding voltage and current are measured to control the secondary winding load, as its variation may also be responsible for changes in current error and phase displacement (Figure 7D). This test was performed for room temperature +25 °C (Figure 2) and −25 °C ambient operation temperature of tested iCT obtained inside the freezer (Figure 3). The results confirmed the statement provided in the standard IEC 61869-2 that iCT accuracy performance is independent from the external operating conditions [27]. However, the change in the transformation accuracy is observed during all 2 h of the test.

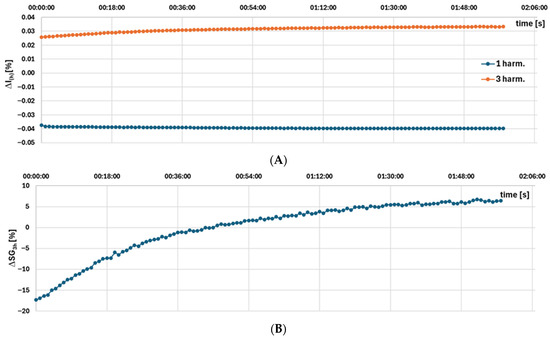

In Figure 8, the measurement results for the model E iCT, obtained using the setup presented in Figure 2 (test with the single primary conductor at rated exploitation conditions). The parameters include (A) current error, (B) percentage change in the self-generated third harmonic relative to the average measured value, and (C) phase displacement.

Figure 8.

Measurement results for the model E iCT, obtained using the setup presented in Figure 1 of: (A) current error, (B) percentage change in the self-generated third harmonic relative to the average measured value and (C) phase displacement.

The results presented in Figure 8A–C indicate that in the case of the 300 A/1 A class 0.2 iCT produced by manufacturer 1, the warm-up time is not required to achieve thermal stability.

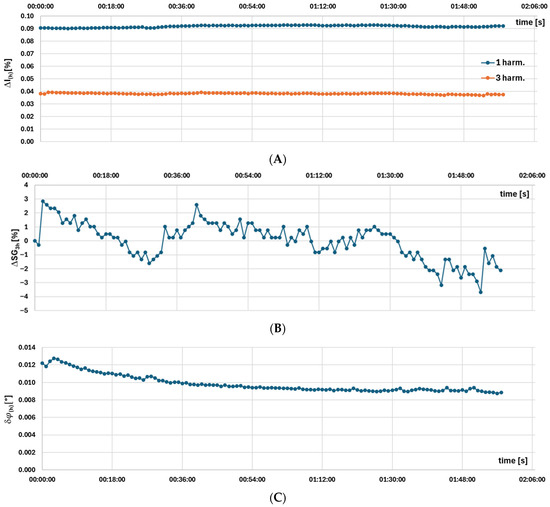

Figure 9 presents the measurement results for the model F iCT, obtained using the setup shown in Figure 2 (test with the single primary conductor at rated exploitation conditions). The evaluated parameters include (A) current error, and (B) percentage change in the self-generated third harmonic relative to the average measured value.

Figure 9.

Measurement results for the model F iCT, obtained using the setup presented in Figure 1 of: (A) current error and (B) percentage change in the self-generated third harmonic relative to the average measured value.

The results presented in Figure 9A indicate a significant change in this case in the current error values (Figure 6A—1 harm). This iCT at the beginning of the warm-up time is outside the 0.5 accuracy class, but after 3 min the current error is below ±0.5%. It also shows a noticeable increase in the self-generated higher harmonics during the first 36 min of the test (Figure 6A—3 harm.). The percentage change in the self-generated third harmonic relative to the average measured value is also substantial (Figure 6B). The diameter of the secondary winding of this iCT is 0.45 mm, and the current density is 6 A/mm2. The temperature of secondary windings increases to 80 °C. Therefore, it can be concluded that the problem of the warm-up time is mainly connected to the too small cross-section/diameter of the secondary winding.

The results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summarized measurement results and parameters of all tested iCTs.

In the case of low-voltage (small) current transformers, the detected changes are minor and practically insignificant for accuracy classes 0.2S and 0.2. Only in one instance—Model F—the iCT outside the specified accuracy class for 50 Hz sinusoidal current before the warm-up period. Therefore, a longer period test is necessary in borderline cases. Even if the secondary winding of this iCT has a diameter of 0.45 mm and a current density of 6 A/mm2 (model C), compared to the value ensured for reference transformers of 2 A/mm2 (model A), the variation in current errors and phase displacement at warm-up time are marginal, while in the case of the iCT model F, such a reduced cross-section in connection with a probable poor magnetic core causes significant changes in transformation accuracy at warm-up time. The absence of detailed winding geometry of models B and E does not compromise the validity or interpretability of the presented results, since the observed effects such as internal heating, warm-up dynamics, and harmonic generation are representative of window-type iCT construction.

3. Analysis of the Influence of Operating Temperature on the Conversion Accuracy of Closed-Loop Current Transducer with a Hall Sensor

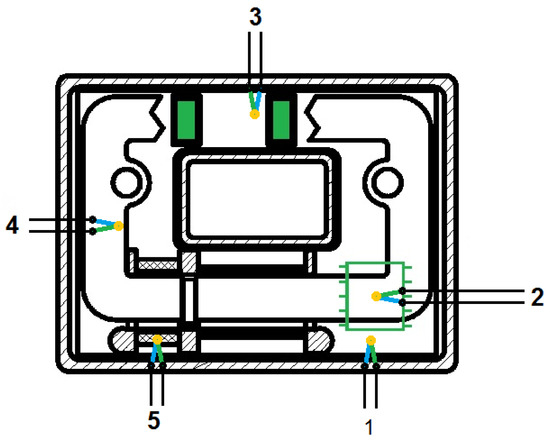

The closed-loop current transducer from the LA 55 series was selected as the subject of this study, as its design allows temperature sensors to be positioned at key points within the system (Figure 10). This configuration made it possible to monitor dynamic temperature variations and determine the stabilization time of the operating temperature.

Figure 10.

Arrangement of temperature sensors in the tested current transducer.

The temperature was monitored in 5 points inside the current transducer as follows:

- TInT: on the internal enclosure within its housing;

- TAH: on the integrated amplifier of the Hall sensor;

- TTC/L: on the transistors driving the current in the closed-loop winding;

- TFe: on the ferromagnetic core;

- TComp: on the compensation winding.

The measured values of temperature for ambient temperature TAmb set by the climatic chamber are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Operating temperatures of the components of the tested closed-loop current transducer with a Hall sensor for different ambient temperatures.

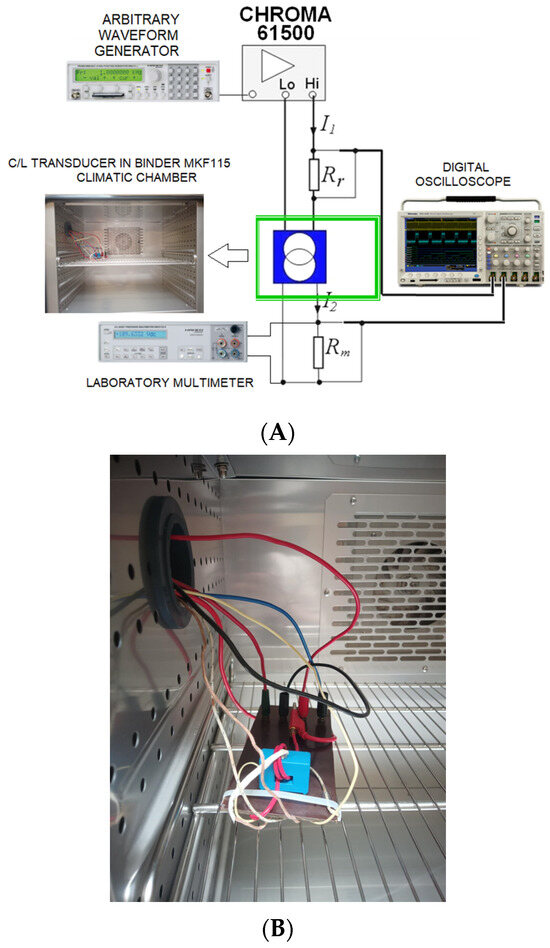

The stabilized temperature values within the transducer housing indicate the need to distinguish between ambient temperature and the system’s operating temperature. To accurately evaluate the influence of temperature on the metrological properties of the transducer, a dedicated measurement system was developed. The setup included a BINDER MKF 115 climatic chamber (BINDER GmbH, Tuttlingen, Germany) (Figure 11). Within the system, an MSO 4104 oscilloscope (RIGOL Technologies, Suzhou (Headquarters), China) was used to measure the frequency of the primary I1 and secondary I2 currents (from voltages across current shunts Rr and Rm), as well as to determine the phase shift between them. A six-digit precision laboratory multimeter (Hameg HM8112) (HAMEG Instruments GmbH, Mainhausen (Hessen), Germany) measured the RMS value of the voltage proportional to the secondary current across the resistor Rm connected to the transducer’s output. The reference primary current was provided by a programmable voltage source (CHROMA 61500) (Chroma ATE Inc., Taoyuan City, Taiwan), which amplified voltage from an external arbitrary waveform generator (HM 8131-2). This configuration enabled the characterization of transducer properties at a rated primary current RMS value equal to 10 A not only under sinusoidal excitation but also for distorted current, extending the analysis to the 10 kHz frequency range of the main component.

Figure 11.

System for testing the influence of operating temperature on the conversion accuracy of closed-loop current transducer with a Hall sensor: (A) electrical diagram, (B) photo.

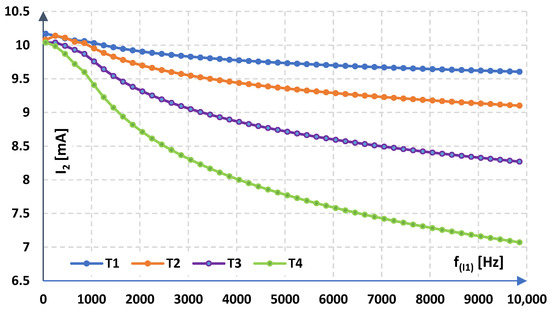

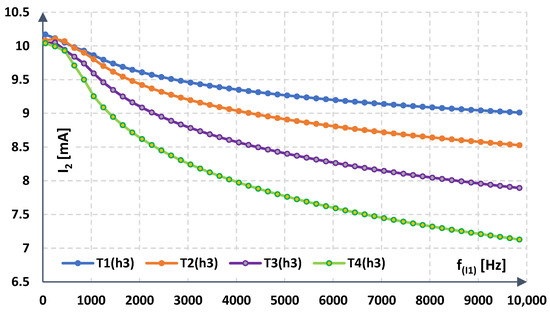

Figure 12 shows how the RMS values of the sinusoidal secondary current vary with the frequency of the primary current at different ambient temperatures.

Figure 12.

RMS value of the secondary current for the RMS value of the primary current equal to 10 A at ambient temperatures TAmb (internal TInT): T1 equal to 25 °C (46 °C), T2 equal to 65 °C (84 °C), T3 equal to 125 °C (143 °C), T4 equal to 145 °C (164 °C).

The results from Figure 12 show a significant decrease in the relative gain error of the tested current transducer (especially at higher frequencies) as the secondary current from the rated RMs value of the primary current is reduced in relation to the rated RMS value equal to 10 mA.

The changes in the RMS values of the secondary current with the frequency of the primary current distorted with a third harmonic (30% level) for tested ambient temperatures are shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

RMS value of the secondary current for the RMS value of the primary current equal to 10 A with 30% level of third harmonic at ambient temperatures TAmb (internal TInT): T1 equal to 25 °C (46 °C), T2 equal to 65 °C (84 °C), T3 equal to 125 °C (143 °C), T4 equal to 145 °C (164 °C).

In this test scenario, the results from Figure 13 show a further decrease in the relative gain error of the tested current transducer in relation to its rated RMS value equal to 10 mA.

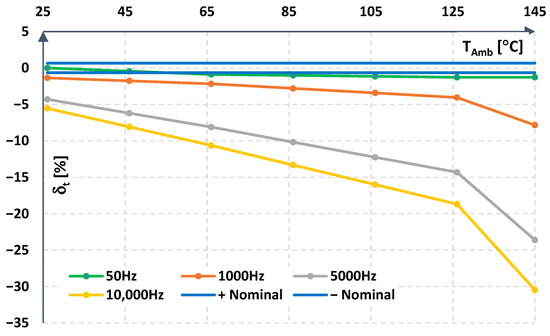

Figure 14 shows the relative error values obtained when converting the sinusoidal primary current to the secondary current across ambient temperatures ranging from 25 °C to 145 °C at the selected primary current frequency.

Figure 14.

Relative error obtained when converting the primary current to the secondary current across ambient temperatures ranging from 25 °C to 145 °C, at the selected sinusoidal primary current frequency.

In Figure 14 and Figure 15, the following abbreviations are used: +Nominal, −Nominal—limiting values of the maximum conversion error δmax declared by the manufacturer.

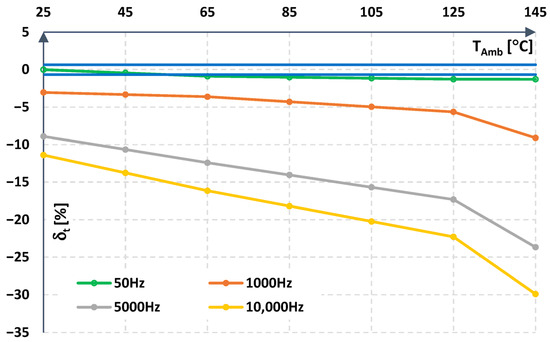

Figure 15.

Relative error obtained when converting the distorted primary current with 30% third harmonic level to the secondary current across ambient temperatures ranging from 25 °C to 145 °C at the selected primary current main component frequency.

Figure 15 shows the relative error values obtained when converting the distorted primary current with a 30% third harmonic level to the secondary current across ambient temperatures ranging from 25 °C to 145 °C at the selected primary current frequency.

In Figure 12 and Figure 14, a noticeable deterioration in the conversion accuracy of the sinusoidal current can be observed. The decisive factor is the change in the geometric parameters of the magnetic core, which alters its reluctance and thereby the impedance of the closed-loop current transducer’s compensation circuit. This causes the load on the transistors driving the compensation circuit to change as well. In Figure 13 and Figure 15, the results are presented for a test scenario in which the signal contains a third harmonic in phase with the fundamental. This signal exhibits a higher slew rate than a pure sinusoidal waveform, and the resulting increase in the compensation circuit’s impedance further deteriorates the conversion accuracy of the tested closed-loop current transducer. This is demonstrated by the lower RMS value of the secondary current waveform distorted with a third harmonic, shown in Figure 13 compared to Figure 12, as well as by the increased relative conversion error curve in Figure 15 compared to the results in Figure 14. According to the authors, due to the operation of the transducer in a closed-loop configuration, the influence of changes in the parameters of semiconductor components can be considered negligible, while changes in the geometry of the magnetic core are dominant. This is related to the design of the power amplifier as a transconductance circuit implemented in the form of a complementary transistor pair. The operating temperature of current conversion systems, particularly in high-power devices, can reach elevated levels. Under such conditions, a significant increase in the value of the relative gain error may occur, even exceeding the permissible level specified by the manufacturer.

4. Conclusions

This study examined the thermal behavior and transformation accuracy of inductive current transformers (iCTs) and active closed-loop, zero-flux transducers under varying internal and ambient temperature conditions. Eighteen iCTs were tested, and six representative units were selected for detailed presentation based on their clarity and relevance. The tests confirmed that, in line with IEC 61869-2, the accuracy performance of iCTs is independent of external environmental conditions such as ambient temperature and humidity, even under extreme simulated scenarios from +50 °C to −25 °C and relative humidity ranging from 10% to 90%. However, internal thermal effects—resulting from the secondary current RMS value, secondary winding diameter, and the consequent heating of both the magnetic core and the secondary winding—were observed to influence the transformation accuracy during operation, particularly in the warm-up phase. The magnitude and nature of this influence varied among the tested units. For example, some iCTs showed an improvement in current error and phase displacement over time as temperature stabilized, while others experienced deterioration. In several cases, the magnitude of the self-generated third harmonic increased during the warm-up period, depending on the amplitude of the fundamental current and the thermal characteristics of the winding. Observed warm-up times ranged from a few minutes to nearly two hours, with temperature increases in the secondary windings reaching up to 85 °C in some units. These findings highlight that while external factors may have minimal effect on iCT’s transformation accuracy, internal heating may be required to obtain the current error value required by a given accuracy class. Moreover, the need for a warm-up period is mainly caused by the secondary winding’s insufficient cross-sectional area or diameter. Therefore, in applications demanding high transformation accuracy, particularly in precision measurements, it is essential to consider internal thermal drift and the necessary stabilization time when evaluating the iCT’s transformation accuracy. This involves allowing appropriate warm-up periods and optimizing the transformer design to reduce sensitivity to self-heating, since the secondary current RMS value is fixed at 1 A or 5 A.

In the case of a closed-loop current transducer with a Hall sensor, the increased gain error caused by the internal operation temperature rise should be considered significant. Due to the presence of an air gap, temperature variations affect the geometric dimensions of the magnetic circuit, thereby reducing the conversion accuracy of primary current. Presented results indicate that this influence must be considered when determining the applicability of a transducer for usage in elevated temperature environments. The main source of increased gain error is the rise in the magnetic core’s reluctance, which degrades the performance of the transducer’s magnetic flux compensation circuit. The third harmonic component in the primary current increases the current slew rate, further reducing conversion accuracy due to the resulting rise in the impedance of the compensation circuit. This effect was verified through measurements of the secondary current and analysis of the defined relative gain error.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K. and A.S.; methodology, M.K. and A.S.; validation, M.K. and A.S.; formal analysis, M.K. and A.S.; investigation, M.K. and A.S.; resources, M.K. and A.S.; data curation, M.K. and A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K. and A.S.; writing—review and editing, M.K. and A.S.; visualization, M.K. and A.S.; supervision, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, N.; Zhang, P.; Cheng, H. Research of magnetic properties of nanocrystalline materials considering temperature effects. AIP Adv. 2025, 15, 025315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladjimi, A.; Mekideche, M.; Abdesselam, B. Thermal effects on magnetic hysteresis modeling. Arch. Electr. Eng. 2012, 61, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozdur, R.; Gębara, P.; Chwastek, K. A Study of Temperature-Dependent Hysteresis Curves for a Magnetocaloric Composite Based on La(Fe, Mn, Si)13-H Type Alloys. Energies 2020, 13, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebara, P.; Pawlik, P. Broadening of temperature working range in magnetocaloric La(Fe,Co,Si)13- based multicomposite. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2017, 442, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letizia, P.S.; Crotti, G.; Femine, A.D.; Gallo, D.; Iodice, C.; Landi, C.; Luiso, M.; Signorino, D.; Giordano, D. Impact of Temperature on Nonlinearity of Voltage Transformers in Harmonics Measurement. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 9002409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letizia, P.S.; Crotti, G.; Mingotti, A.; Tinarelli, R.; Chen, Y.; Mohns, E.; Agazar, M.; Istrate, D.; Ayhan, B.; Çayci, H.; et al. Characterization of Instrument Transformers under Realistic Conditions: Impact of Single and Combined Influence Quantities on Their Wideband Behavior. Sensors 2023, 23, 7833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingotti, A.; Bartolomei, L.; Peretto, L.; Tinarelli, R. On the Long-Period Accuracy Behavior of Inductive and Low-Power Instrument Transformers. Sensors 2020, 20, 5810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, M. Nonlinearity of the magnetization characteristic of the magnetic core in calculation of current error and phase displacement values of inductive CTs. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, M.; Blus, K. Analytical Investigation of Primary Waveform Distortion Effect on Magnetic Flux Density in the Magnetic Core of Inductive Current Transformer and Its Transformation Accuracy. Sensors 2025, 25, 4837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, M. Operating Properties of the Inductive Current Transformer and Evaluation of Requirements for Its Compliance with the IEC 61869-1 WB2 Class Extension for Frequency up to 20 kHz. Energies 2025, 18, 2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, M. Routine Testing–Oriented Method for Evaluating Inductive Current Transformers Accuracy Under Harmonic Distortion Based on Maximum Current Error and Phase Displacement. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 137491–137504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballal, M.S.; Wath, M.G.; Suryawanshi, H.M. A novel approach for the error correction of CT in the presence of harmonic distortion. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2019, 68, 4015–4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, A.J.; Femine, A.D.; Gallo, D.; Langell, R.; Luiso, M. Compensation of current transformers’ nonlinearities by tensor linearization. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2019, 68, 3841–3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurano, C.; Toscani, S.; Zanoni, M. A Simple Method for Compensating Harmonic Distortion in Current Transformers: Experimental Validation. Sensors 2021, 21, 2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faifer, M.; Laurano, C.; Ottoboni, R.; Toscani, S. Adaptive Polynomial Harmonic Distortion Compensation in Current and Voltage Transformers Through Iteratively Updated QR Factorization. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 9001810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohns, E.; Fricke, S.; Pauling, F. An AC power amplifier for testing instrument transformer test equipment. In Proceedings of the Conference on Precision Electromagnetic Measurements (CPEM 2016), Ottawa, ON, Canada, 10–15 July 2016; pp. 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristaldi, L.; Faifer, M.; Laurano, C.; Ottoboni, R.; Toscani, S.; Zanoni, M. A Low-Cost Generator for Testing and Calibrating Current Transformers. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2019, 68, 2792–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetrio, A.; Faifer, M.; Laurano, C.; Ottoboni, R.; Toscani, S. Implementation of Low-Cost High-Performance Generators for Testing the Harmonic Measurement Accuracy of Instrument Transformers. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 9003613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataliotti, A.; Cosentino, V.; Crotti, G.; Giordano, D.; Modarres, M.; Di Cara, D.; Tinè, G.; Gallo, D.; Landi, C.; Luiso, M. Metrological performances of voltage and current instrument transformers in harmonics measurements. In Proceedings of the I2MTC 2018—2018 IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference: Discovering New Horizons in Instrumentation and Measurement, Houston, TX, USA, 14–17 May 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Portas, R.; Colombel, L. Accuracy of Hall-Effect Current Measurement Transducers in Automotive Battery Management Applications using Current Integration. In Proceedings of the Automotive Power Electronics, Paris, France, 26–27 September 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Heumann, D.; Reichert, K. Closed Loop Current Sensors with Magnetic Probe. In Proceedings of the ECPE Seminar Sensors in Power Electronics, Erlangen, Germany, 14–15 March 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sixdenier, F.; Raulet, M. Current Sensor Modeling with A FE-Tuned MEC: Parameters Identification Protocol. Proc. IEEE Sens. J. 2012, 12, 859–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Long, Z.; Liang, S.; Yue, C.; Yin, X.; Zhou, F. Optimal design of dual air-gap closed-loop TMR current sensor based on minimum magnetic field uniformity coefficient. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Q.; Huang, Y.; Shen, Y. Magnetic signature analysis for smart security system based on TMR magnetic sensor array. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 19, 3149–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Phan, K.; Boeve, H.; Vanhelmont, F.; Ikkink, T.; Talen, W. Geometry optimisation of TMR current sensors for on-chip IC testing. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2005, 41, 3685–3687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 61869-1; Instrument Transformers—Part 1: General Requirements. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- IEC 61869-2; Instrument Transformers—Part 2: Additional Requirements for Current Transformers. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).