Experimental Study on the Factors Influencing the Heat Transfer Coefficient of Vertical Tube Indirect Evaporative Coolers

Abstract

1. Introduction

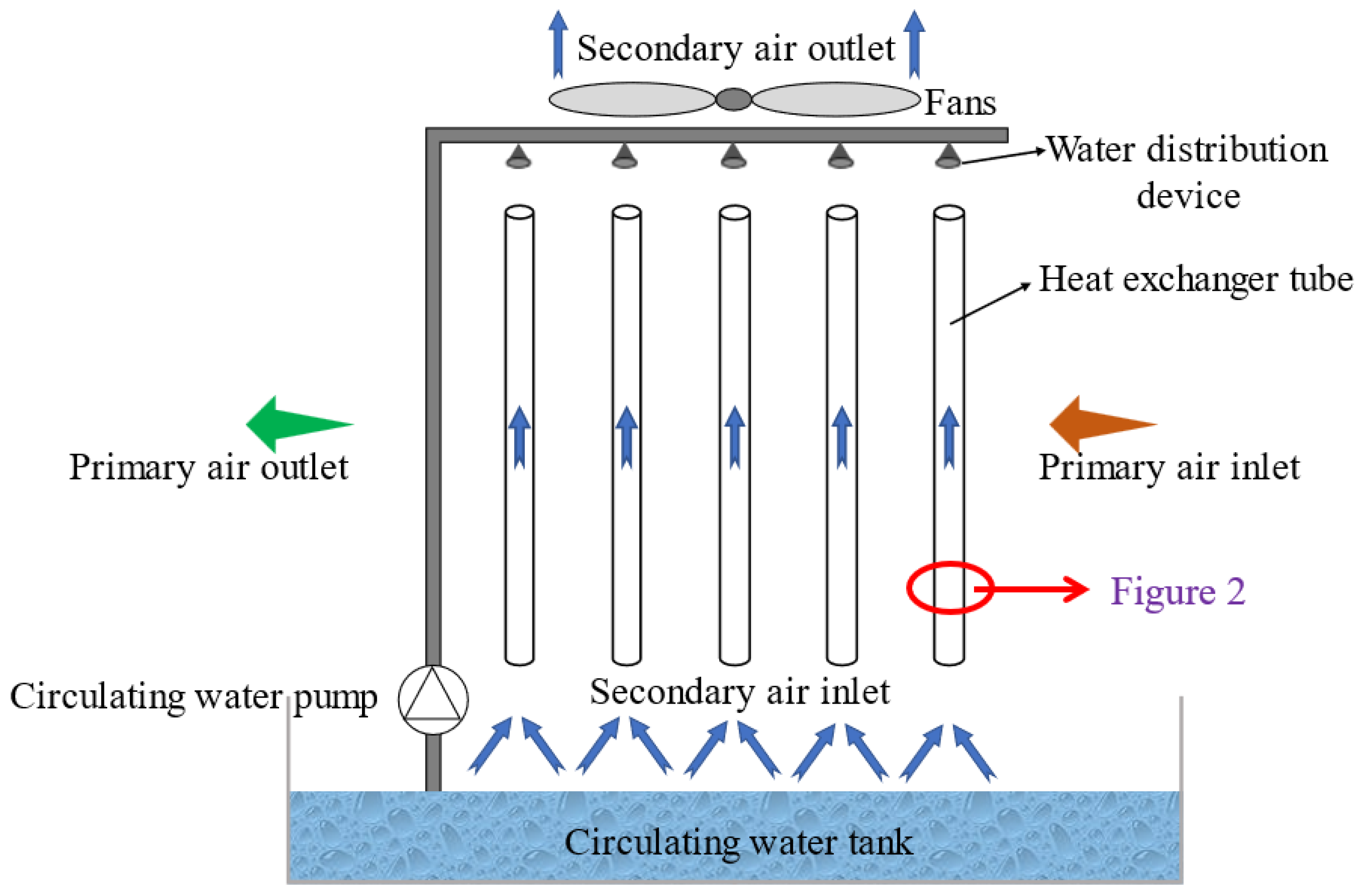

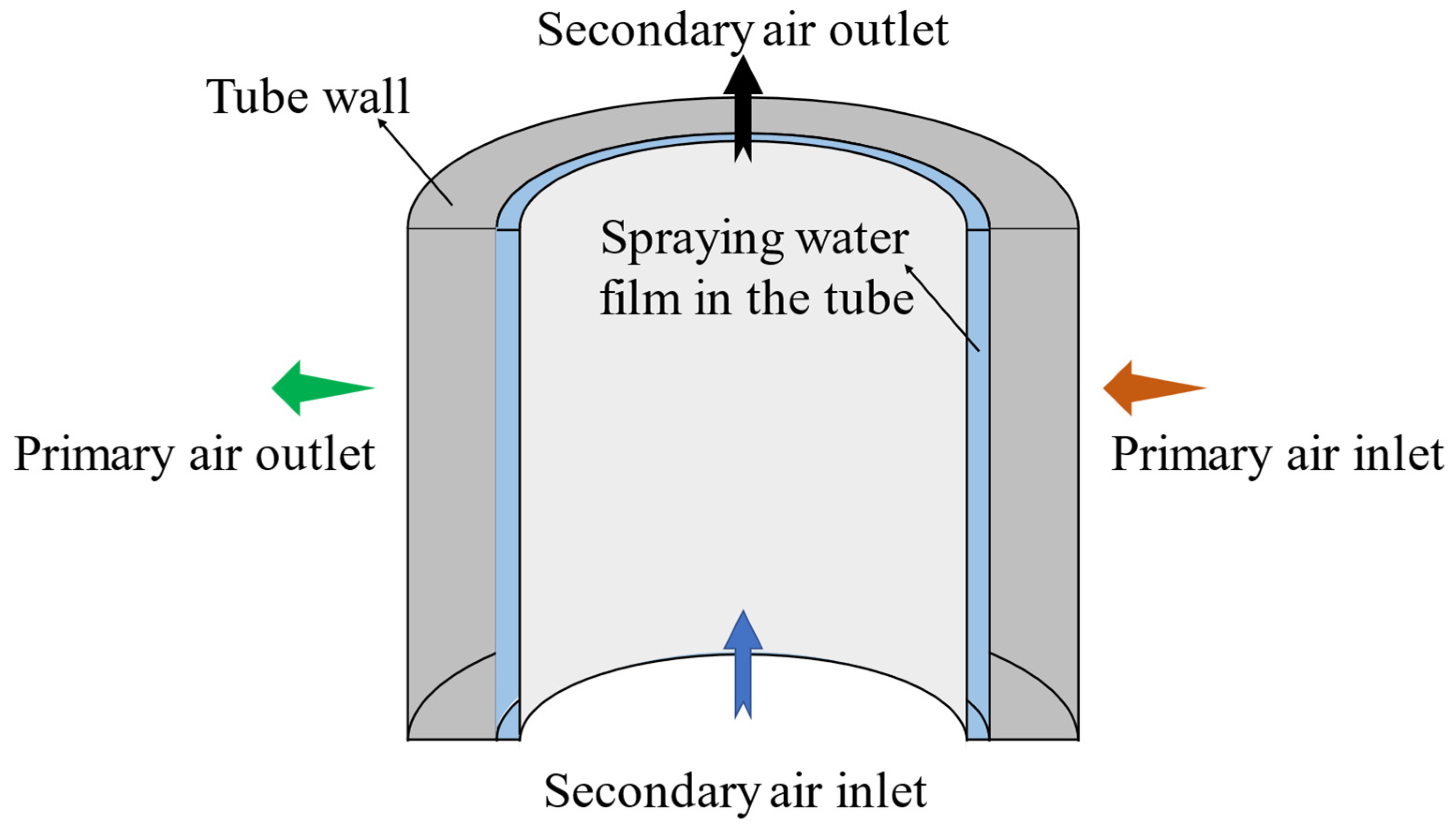

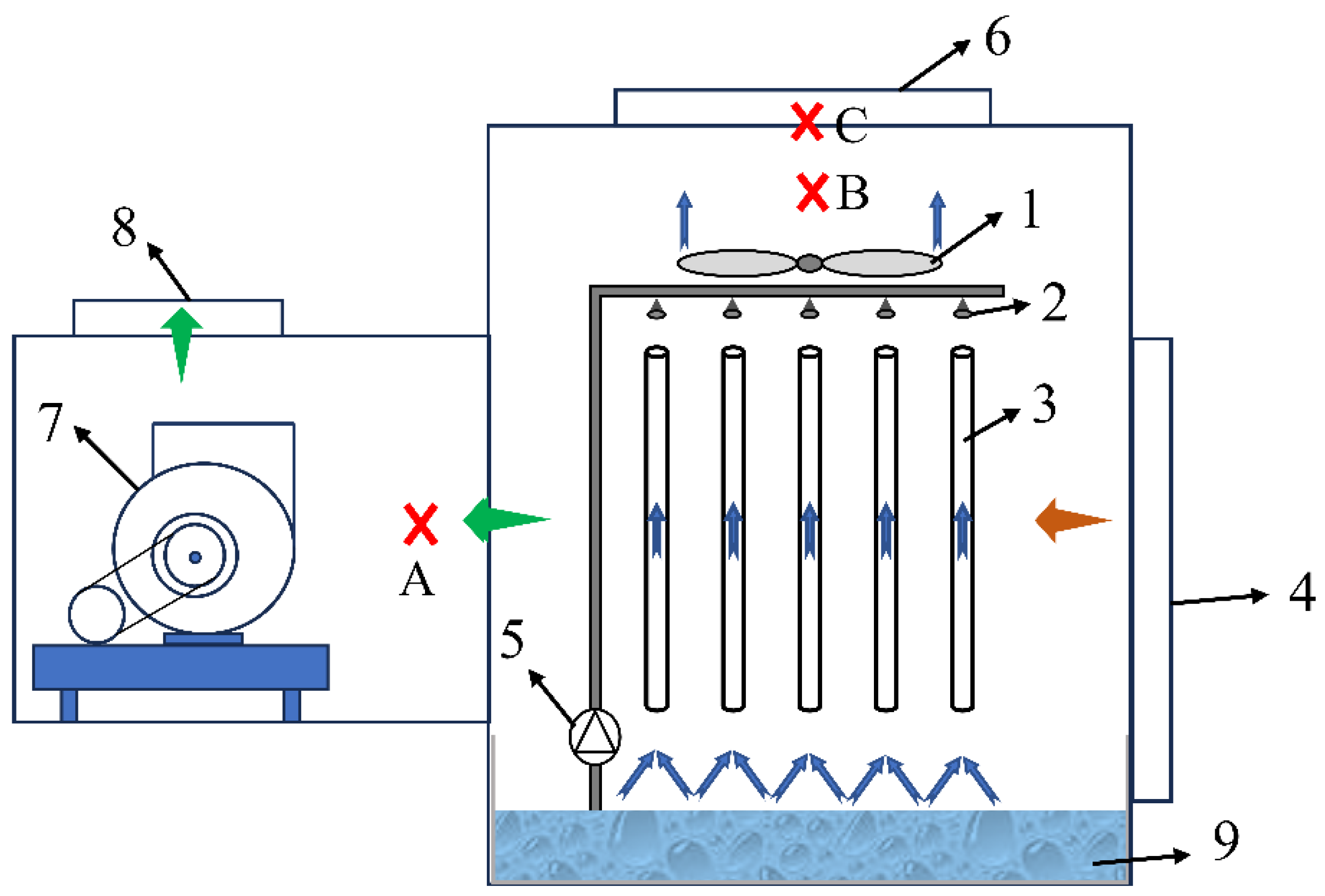

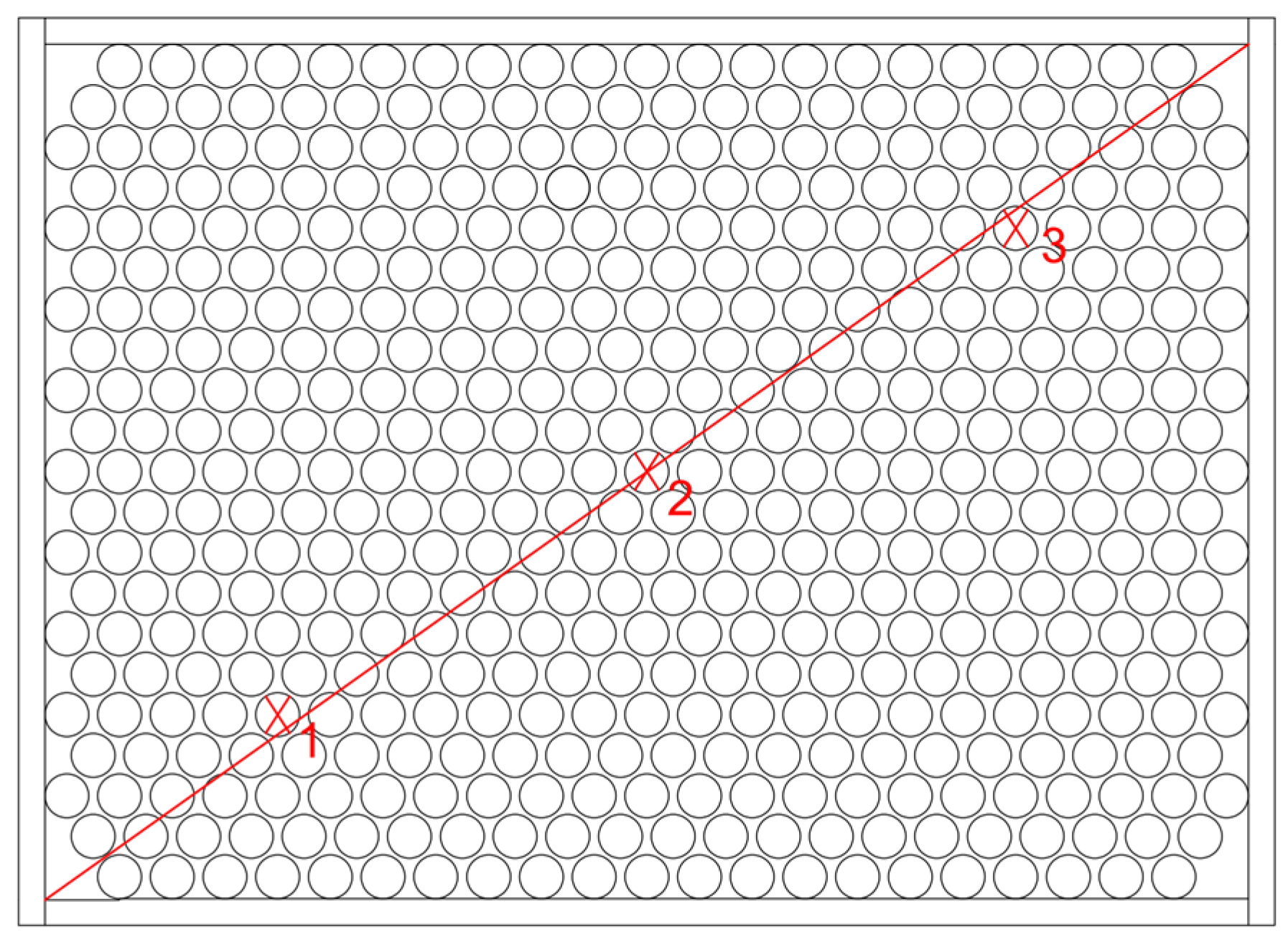

2. Experimental Design

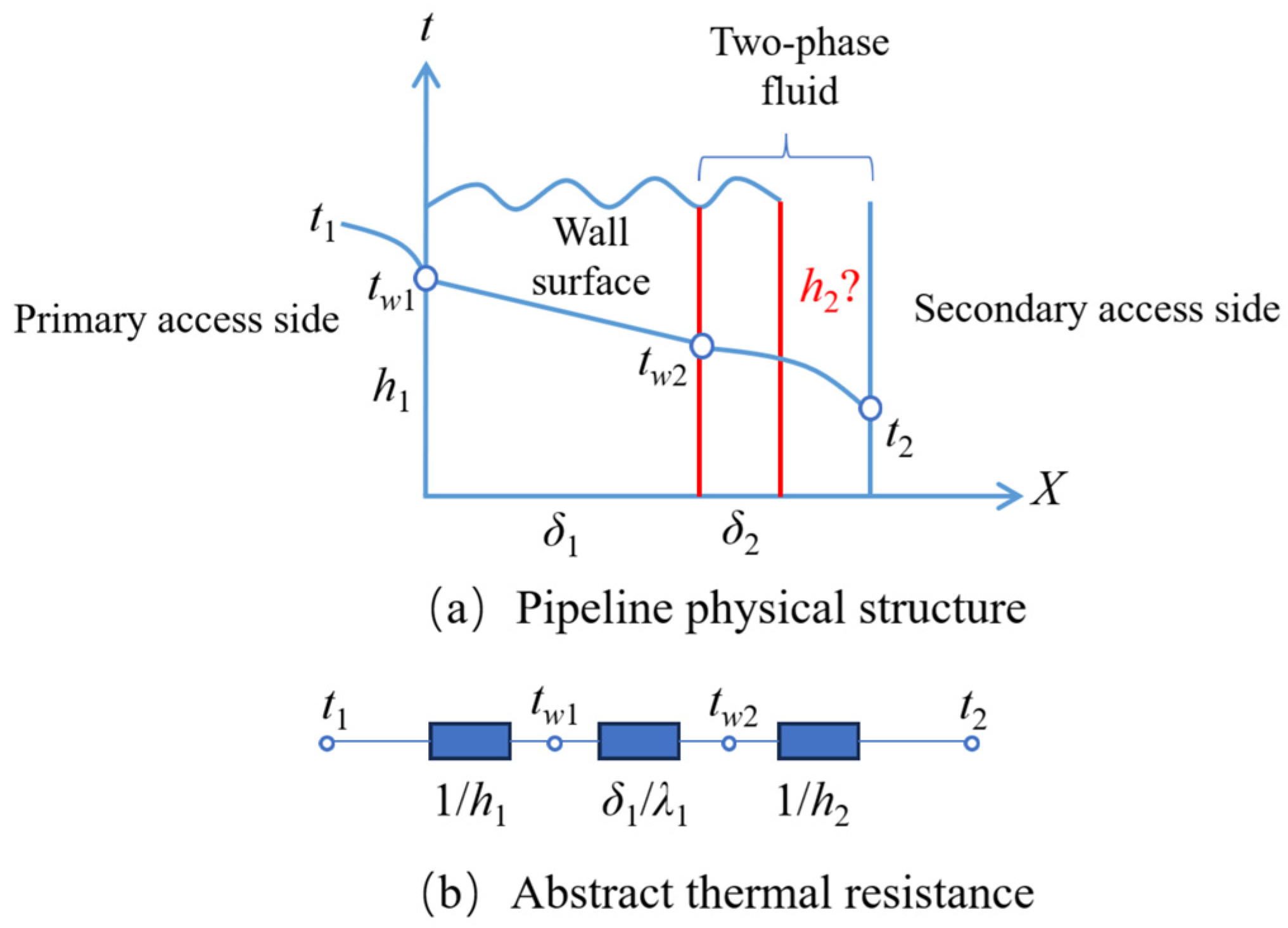

2.1. Theoretical Model

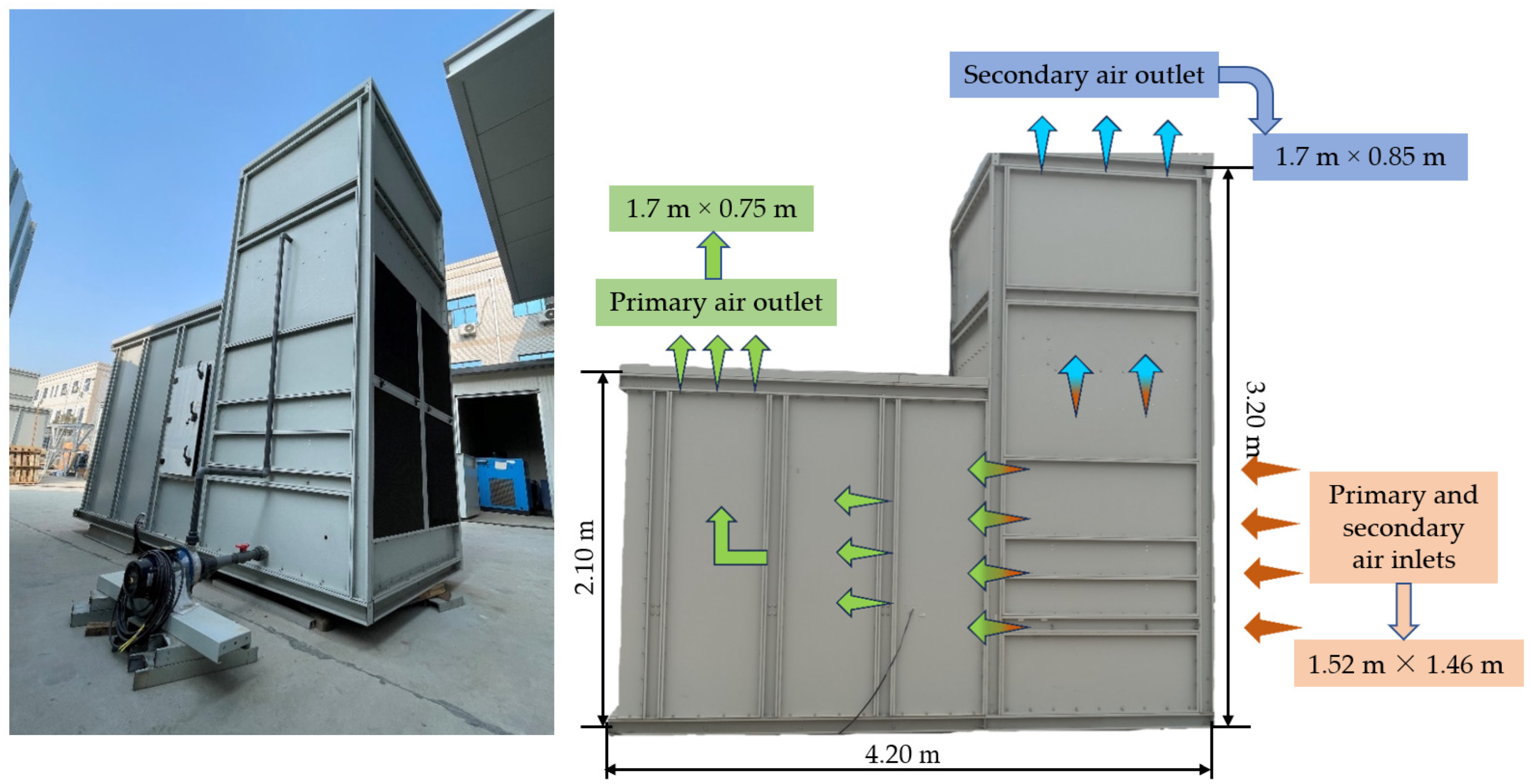

2.2. Experimental Procedure

2.3. Uncertainty Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

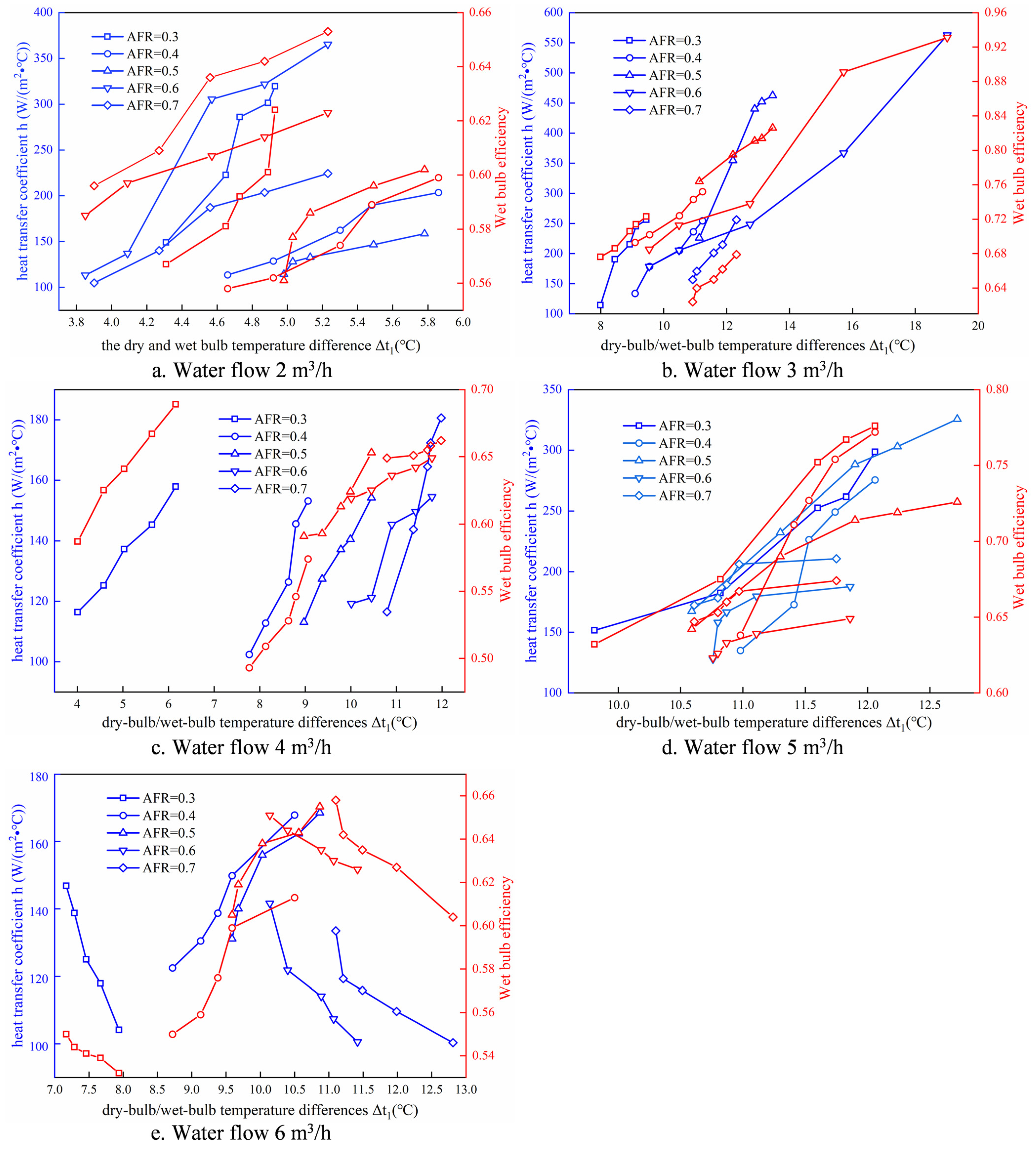

3.1. Effects of the Outdoor Dry-Bulb/Wet-Bulb Temperature Differences

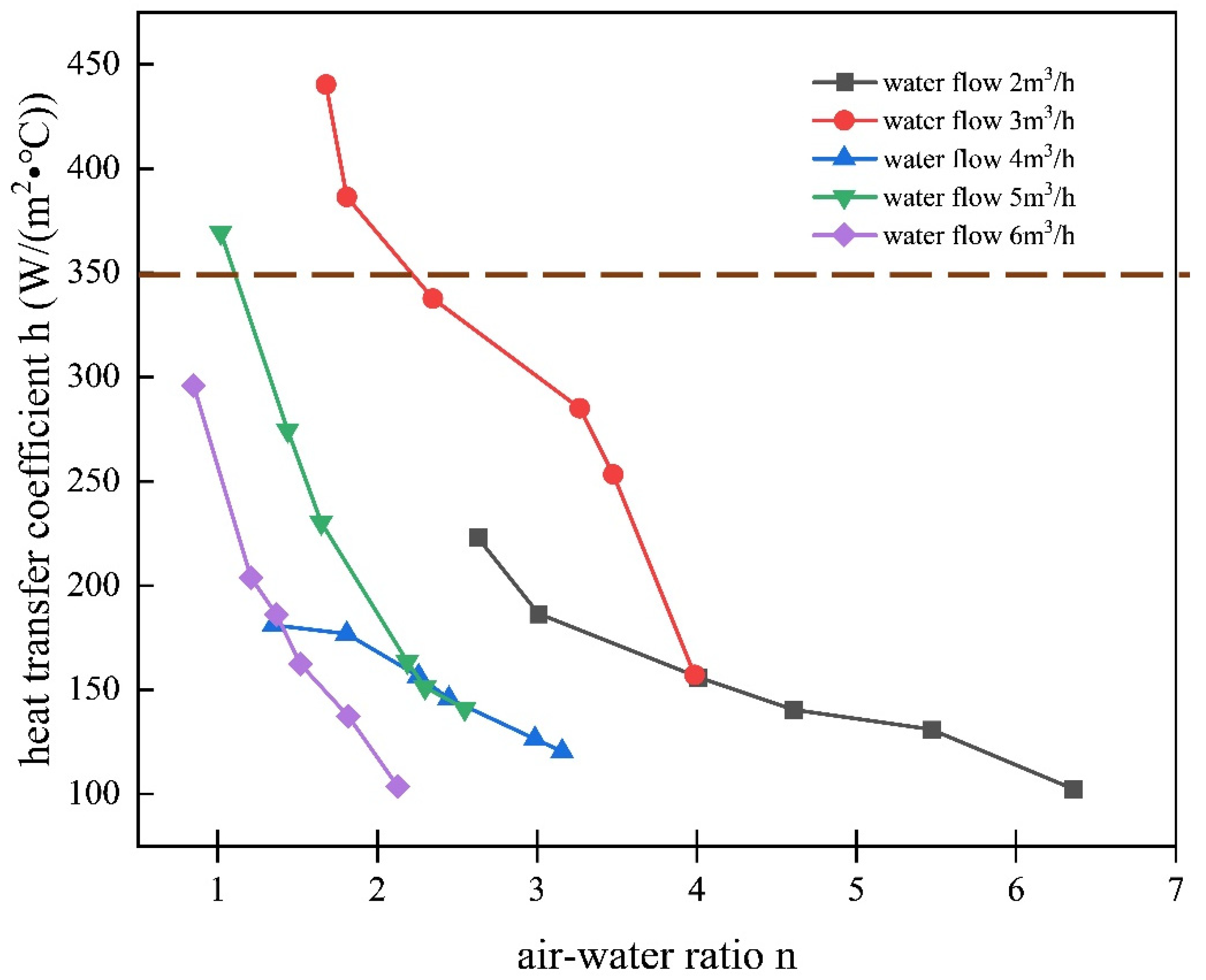

3.2. Effect of the Air-Water Ratio

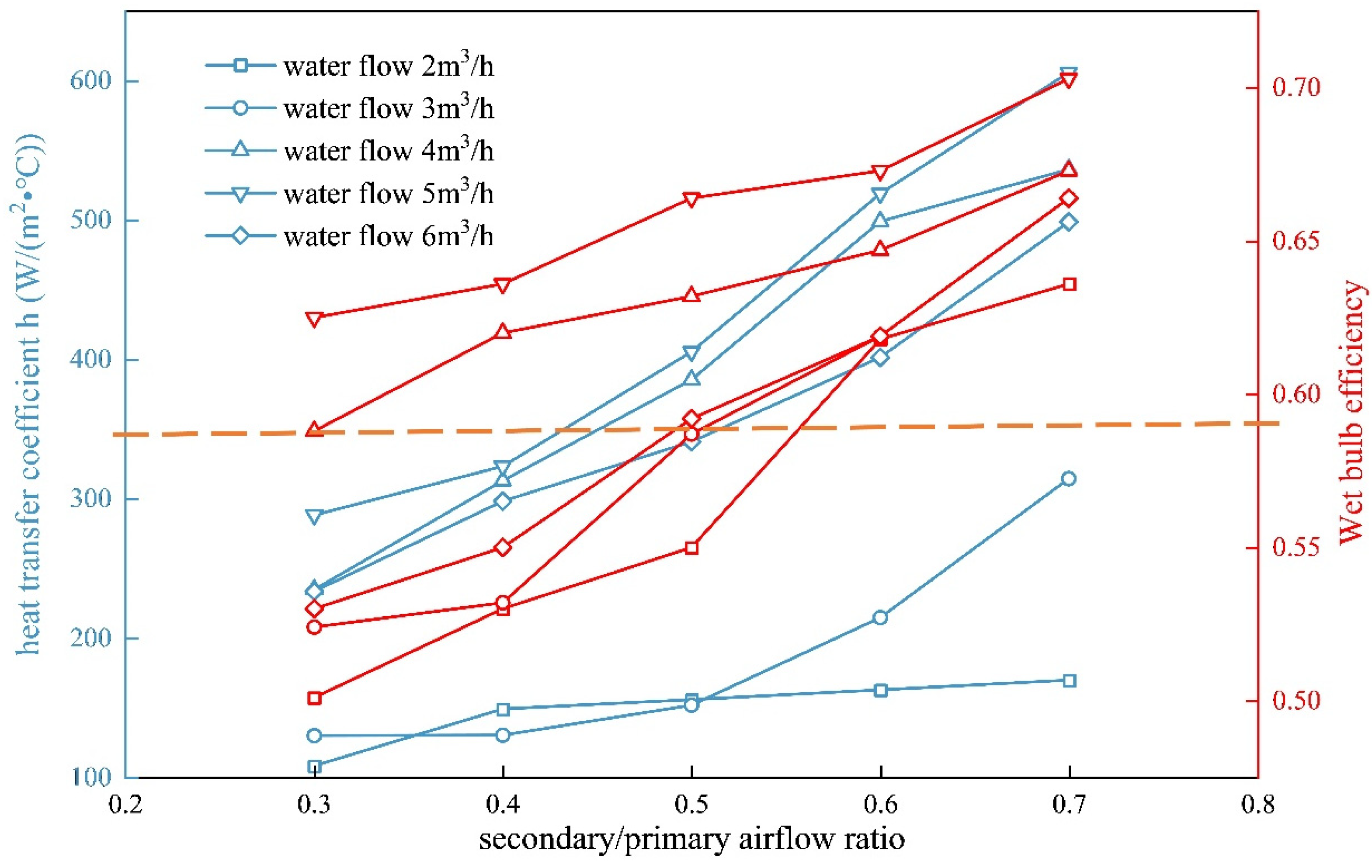

3.3. Effects of the Secondary/Primary Airflow Ratio and Water Flow Rate

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The heat transfer coefficient (h2) generally increases with the increase in outdoor dry-bulb/wet-bulb temperature difference. However, excessive water flow rate and unbalanced air volume ratio may reduce the heat exchange efficiency. For optimal performance, the water spray density (qw) should be maintained between 2.07 and 3.46 m3/(m2·h). In addition, installing the unit at a location with a larger dry-bulb/wet-bulb temperature difference can achieve better heat exchange effects.

- (2)

- As the air-to-water ratio increases, the h2 decreases with increasing water flow rate. The larger the water flow rate, the lower the air–water ratio required to achieve the same h2. For wet side h2 exceeding 350 W/(m2·°C), the water injection density should exceed 2.07 m3/(m2·h), and the air–water ratio should be less than 2.5. A water flow rate greater than 3 m3/h is recommended.

- (3)

- Although the experimental verification in this study is mainly for the VTIEC system, the proposed analytical framework and generalized correlations may be applicable to a wider range of IEC system configurations and can be used as future research directions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| A | heat exchanger area (m2); |

| Cp | specific heat capacity at constant pressure (kJ/(kg·°C)); |

| d | equivalent diameter (m); |

| f | the narrowest flow area between two neighboring tubes (m2); |

| F | total circulation area (m2); |

| h | heat transfer coefficient (W/(m2·°C)); |

| if | enthalpy value of saturated air at the water film surface (kJ/kg); |

| ig1 | enthalpy value at the primary air inlet (kJ/kg); |

| ig1′ | enthalpy value at the primary air outlet (kJ/kg); |

| Keq | overall heat transfer coefficient (W/(m2·°C)); |

| L | length of the tube (m); |

| m | mass flow rate (kg/s); |

| N | the number of total vertical tubes; |

| Nu | Nusselt number, ; |

| Pr | Prandtl number, ; |

| Q | Volumetric flow rate (m3/h); |

| qw | water spraying density (m3/(m2·h); |

| Re | Reynolds number, ; |

| S1 | lateral pipe spacing (m); |

| S2 | longitudinal pipe spacing (m); |

| Sw | water spraying area (m2); |

| tf | water film temperature (°C); |

| tg1 | primary air inlet dry bulb temperature (°C); |

| tg1′ | primary air outlet dry bulb temperature (°C); |

| tg2 | secondary air inlet dry bulb temperature (°C); |

| tg2’ | secondary air outlet dry bulb temperature (°C); |

| ts | wet bulb temperature (°C); |

| TW | tube wall temperature (°C); |

| u | airflow velocity (m/s); |

| X | number of tubes on the windward side. |

Greek Symbols

| α | thermal diffusivity, (m2/s); |

| δ | thickness of heat conduction medium (m); |

| Δim | log mean enthalpy difference (kJ/kg); |

| Δtm | log mean temperature difference (°C); |

| ΔTdb | dry-bulb temperature difference; |

| ΔTwb | wet-bulb temperature difference; |

| εZ | tube bank correction factor; |

| λ | thermal conductivity (W/(m·°C)); |

| ν | fluid motion viscosity coefficient (m2/s); |

| ρ | density (kg/m3); |

| Φ | Overall Heat transfer quantity (W); |

| φ | relative humidity (%RH). |

Abbreviations

| AFR | secondary/primary airflow ratio; |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics; |

| DEC | Direct evaporative cooler; |

| HTC | Heat transfer coefficient; |

| IEC | Indirect evaporative cooler; |

| LMTD | Logarithmic mean temperature difference; |

| VTIEC | Vertical tube indirect evaporative cooler. |

References

- Jamil, M.A.; Shahzad, M.W.; Xu, B.B.; Imran, M.; Ng, K.C.; Zubair, S.M.; Markides, C.N.; Worek, W.M. Energy-efficient indirect evaporative cooler design framework: An experimental and numerical study. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 292, 117377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laknizi, A.; Mahdaoui, M.; Abdellah, A.B.; Anoune, K.; Bakhouya, M.; Ezbakhe, H. Performance analysis and optimal parameters of a direct evaporative pad cooling system under the climate conditions of Morocco. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2019, 13, 100362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, J.K.; Hindoliya, D.A. Experimental performance of new evaporative cooling pad materials. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2011, 1, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, F. On-site experimental testing of a novel dew point evaporative cooler. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 3475–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Cui, G.; Lan, C.Q. Developments in evaporative cooling and enhanced evaporative cooling—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 113, 109230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, U.; Abbas, N.; Hamid, K.; Abbas, S.; Hussain, I.; Ammar, S.M.; Sultan, M.; Ali, H.M.; Hussain, M.; Rehman, T.-U.; et al. A review of recent advances in indirect evaporative cooling technology. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 122, 105140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, S.; Sarkar, J.; Kumar, A. Proposal and month-wise performance evaluation of a novel dual-mode evaporative cooler. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 55, 3523–3536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Zhan, C.; Zhang, X.; Mustafa, M.; Zhao, X.; Alimohammadisagvand, B.; Hasan, A. Indirect evaporative cooling: Past, present and future potentials. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 6823–6850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Huang, X.; Jia, C.; Du, D.; Xu, J. Design and Applicability Study of Vertical Tube Indirect Evaporative Cooler. Liuti Jixie 2020, 48, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Pandelidis, D.; Cichoń, A.; Pacak, A.; Drąg, P.; Drąg, M.; Worek, W.; Cetin, S. Water desalination through the dewpoint evaporative system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 229, 113757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Yang, C.; Yan, W.; Zhang, L.; Wan, Y.; Chua, K.J. Experimental study on a moisture-conducting fiber-assisted tubular indirect evaporative cooler. Energy 2023, 278, 128014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Tang, T.; Yang, C.; Yan, W.; Cui, X.; Chu, J. Cooling performance and optimization of a tubular indirect evaporative cooler based on response surface methodology. Energy Build. 2023, 285, 112880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Tang, T.; Ma, J.; Yan, Y.; Fu, T.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Shen, H.; Huan, C. Experimental study on the flow resistance of inner tube and characteristics of drifting water in a tubular indirect evaporative cooler. Int. J. Refrig. 2024, 160, 275–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohani, A.; Sayyaadi, H. Thermal comfort based resources consumption and economic analysis of a two-stage direct-indirect evaporative cooler with diverse water to electricity tariff conditions. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 172, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Huang, X.; Qu, Y.; Wang, F.; Chen, Y. Theoretical and Experimental study on Heat and Mass Transfer of A Porous Ceramic Tube Type Indirect Evaporative Cooler. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 173, 115211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Sun, H.; Tang, T.; Yan, Y.; Li, P. Experimental Study on the Thermal Performances of a Tube-Type Indirect Evaporative Cooler. Fluid Dyn. Mater. Process. 2023, 19, 2519–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Chen, Q. Optimization criteria for the performance of heat and mass transfer in indirect evaporative cooling systems. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2012, 57, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A. Going below the wet-bulb temperature by indirect evaporative cooling: Analysis using a modified ε-NTU method. Appl. Energy 2012, 89, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajski, K.; Danielewicz, J.; Brychcy, E. Performance Evaluation of a Gravity-Assisted Heat Pipe-Based Indirect Evaporative Cooler. Energies 2020, 13, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Soh, A.; Shao, Y.; Cui, X.; Tang, Y.; Chua, K.J. Numerical study and correlations for heat and mass transfer coefficients in indirect evaporative coolers with condensation based on orthogonal test and CFD approach. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 153, 119580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Bui, D.T.; Wang, R.; Chua, K.J. On the fundamental heat and mass transfer analysis of the counter-flow dew point evaporative cooler. Appl. Energy 2018, 217, 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Shi, W.; Chen, Y.; Min, Y. Research development of indirect evaporative cooling technology: An updated review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 145, 111082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeel, A.E.; Bassuoni, M.M.; Abdelgaied, M. Experimental study of a novel integrated system of indirect evaporative cooler with internal baffles and evaporative condenser. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 138, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana, R.; De Antonellis, S.; Marocco, L.; Guilizzoni, M. Modeling of Indirect Evaporative Cooling Systems: A Review. Fluids 2023, 8, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Aute, V.; Radermacher, R. Uncertainty Analysis on Prediction of Heat Transfer Coefficient and Pressure Drop in Heat Exchangers Due to Refrigerant Property Prediction Error. In Proceedings of the International Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Conference, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 14–17 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Su, M.; Zhang, H.; Liu, C.; Ouyang, X. Design and simulation of a new type of fin-and-tube heat exchanger with trapezoidal slit fins. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 59, 104604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T. Research on Air Conditioning System Driven by Low-Concentration Solution Dehumidification Heat Pump. Master’s Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y. Equivalent Enthalpy Model and Log-Mean Enthalpy Difference Method for Heat-Mass Transfer in Cooling Towers. ASME J. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 146, 104501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Heat Transfer Science, 6th ed.; China Building Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Moffat, R.J. Using Uncertainty Analysis in the Planning of an Experiment. J. Fluids Eng. 1985, 107, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Poole, R.; Zhou, Z. Rate-limiting factors in thin-film evaporative heat transfer processes. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 228, 125629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, X.; Qiu, Q. Study on liquid film thickness and flow characteristics of falling film outside an elliptical tube. Desalination Water Treat. 2019, 157, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E.; Hung, Y.M. Thermocapillary flow in evaporating thin liquid films with long-wave evolution model. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2014, 73, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajal, J.E.; Thome, J.R.; Cavallini, A. Condensation in horizontal tubes, part 1: Two-phase flow pattern map. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2003, 46, 3349–3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Huang, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Qiu, J. A preliminary study on the experiment of vertical tube indirect evaporative cooler. J. Build. Heat Vent. Air Cond. 2015, 34, 52–55. [Google Scholar]

| Instrument Model | Test Content | Measurement Range | Precision Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rotronic HL-1D | dry bulb temperature | −30 °C~70 °C | ±0.3 °C |

| Rotronic HL-1D | humidity level | 0%RH~100%RH | ±3% RH |

| Testo-480 | wind speeds | 0 m/s~+50 m/s | ±0.1 m/s |

| pt100 | water temperature | −50 °C~200 °C | ±0.1 °C |

| Float Flow Meter | water flow rate | 0 m3/h~12 m3/h | ±0.01 m3/h |

| KST-5.0 | hourly water temperatures | −200 °C~2400 °C | 0.2 FS% |

| Tape measure | air outlet size | 0 m~3 m | 1 mm |

| Dry Bulb Temperature tg1/°C | Wet Bulb Temperature ts1/°C | Primary Air Temperature tg1’/°C | Secondary Air Temperature tg2’/°C | Water Flow Rate m3/h | Secondary/Primary Air Flow Ratio (AFR) | Water Film Temperature tf/°C | HTC of Wet Sides h2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26.6 | 21.91 | 23.8 | 23.1 | 2 | 0.3 | 23.7 | 139.22 |

| 25.7 | 20.67 | 22.8 | 21.9 | 2 | 0.5 | 22.8 | 204.48 |

| 28.3 | 21.07 | 24.9 | 21 | 3 | 0.7 | 21.5 | 34.79 |

| 32.9 | 25.77 | 29.7 | 28.5 | 3 | 0.3 | 31.1 | 180.84 |

| 31.8 | 26.06 | 28.25 | 27.8 | 4 | 0.7 | 29 | 130.04 |

| 32.1 | 25.81 | 28.75 | 28.3 | 4 | 0.5 | 29.7 | 558.6 |

| 32.1 | 25.96 | 28.6 | 27.6 | 4 | 0.6 | 30.1 | 924.5 |

| 25.0 | 20.33 | 22.2 | 21.6 | 5 | 0.7 | 21.8 | 248.7 |

| 26.8 | 21.15 | 23.7 | 22.9 | 6 | 0.6 | 23.2 | 136.8 |

| Parameter | Uncertainty (%) |

|---|---|

| temperature | 1.9 |

| relative humidity | 4.0 |

| wind speed | 2.3 |

| wet-bulb efficiency | 10.49 |

| HTC of wet sides | 3.79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, T.; Tian, G.; Li, P.; Li, W.; Sun, H. Experimental Study on the Factors Influencing the Heat Transfer Coefficient of Vertical Tube Indirect Evaporative Coolers. Energies 2025, 18, 5967. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225967

Sun T, Tian G, Li P, Li W, Sun H. Experimental Study on the Factors Influencing the Heat Transfer Coefficient of Vertical Tube Indirect Evaporative Coolers. Energies. 2025; 18(22):5967. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225967

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Tiezhu, Guangyu Tian, Peixuan Li, Wenkang Li, and Huan Sun. 2025. "Experimental Study on the Factors Influencing the Heat Transfer Coefficient of Vertical Tube Indirect Evaporative Coolers" Energies 18, no. 22: 5967. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225967

APA StyleSun, T., Tian, G., Li, P., Li, W., & Sun, H. (2025). Experimental Study on the Factors Influencing the Heat Transfer Coefficient of Vertical Tube Indirect Evaporative Coolers. Energies, 18(22), 5967. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225967