Performance of Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil–Diesel Blends: Ignition and Combustion Insights

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodological Framework

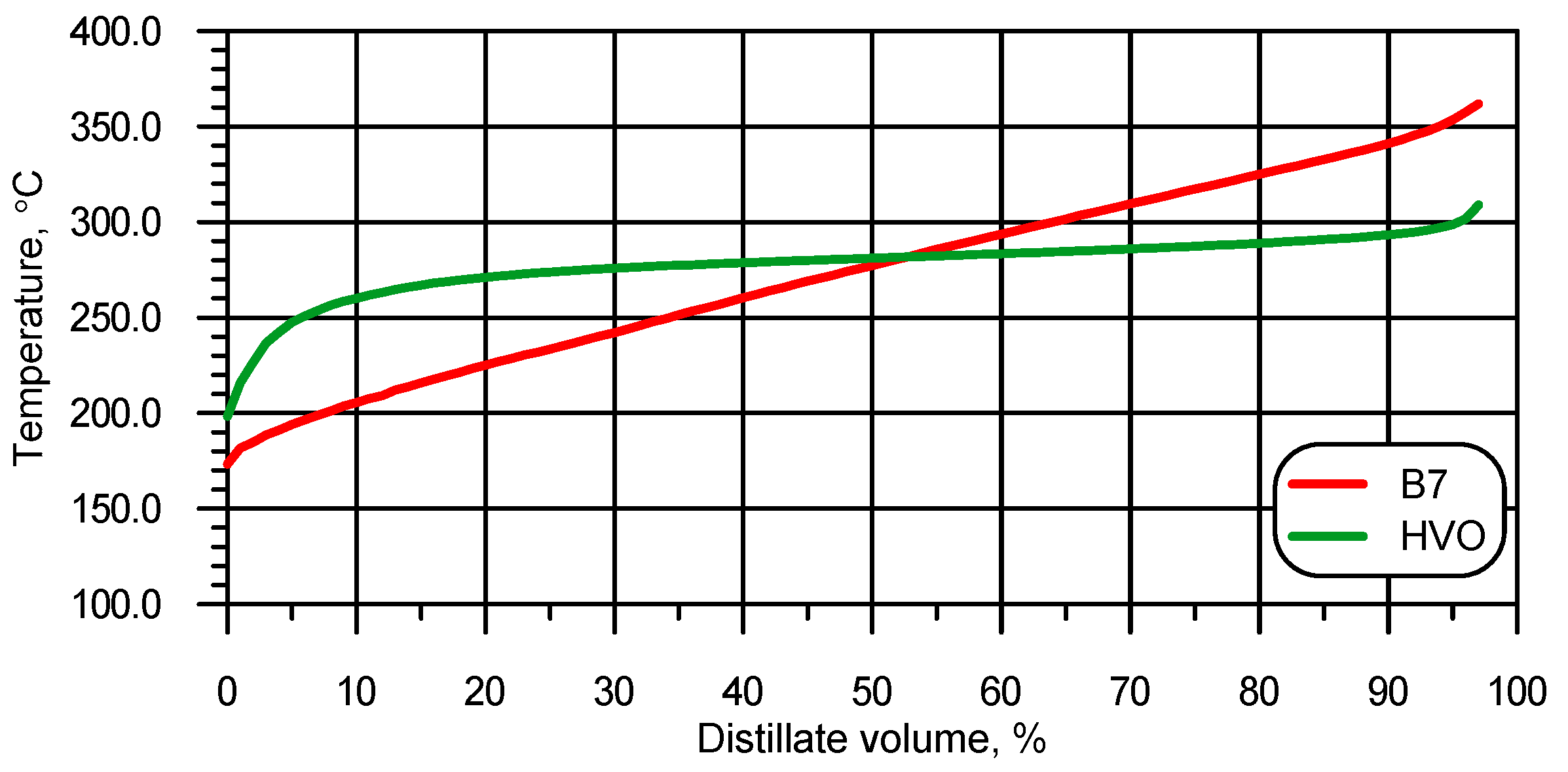

2.1. Composition and Analysis of Tested Fuels

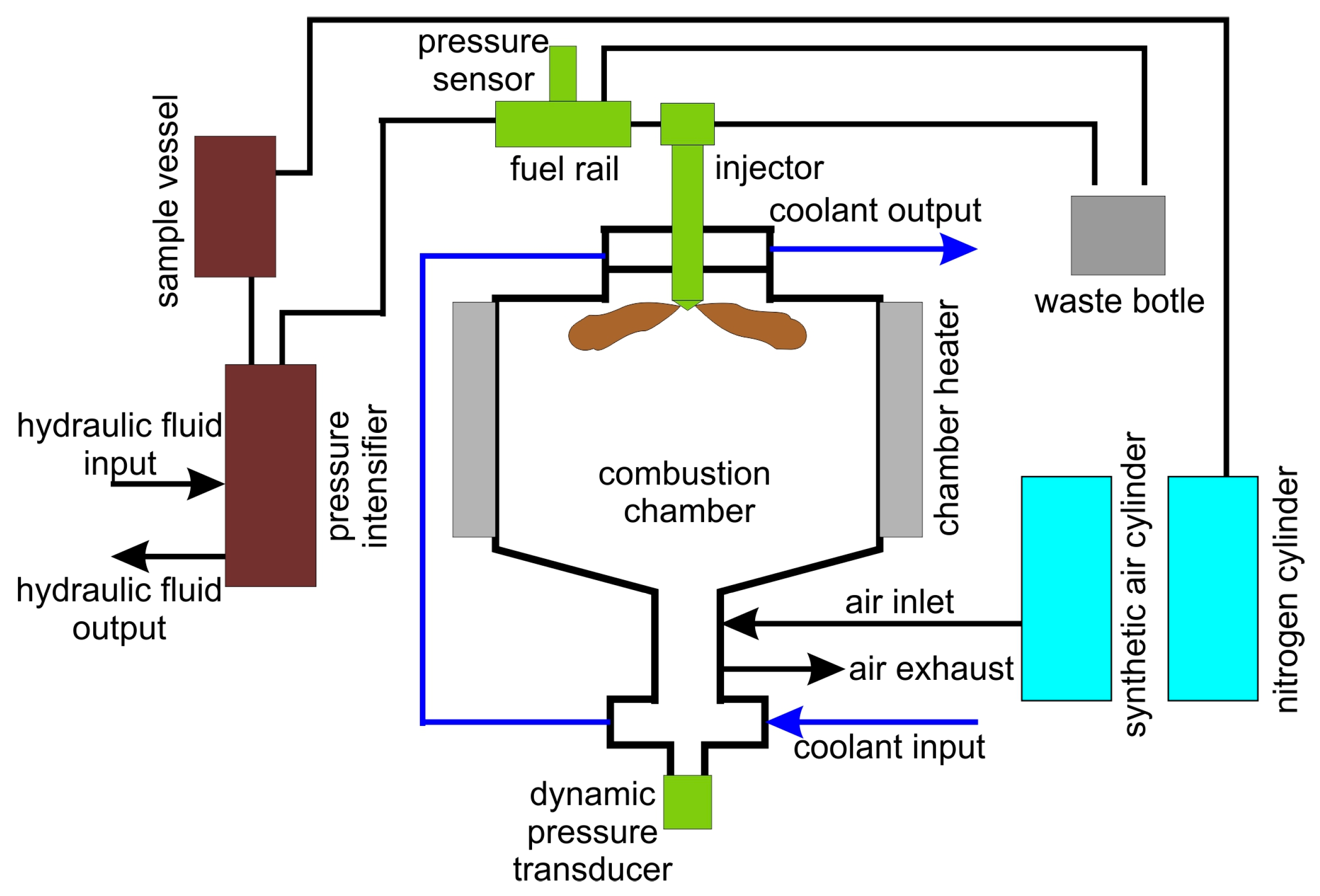

2.2. Description of the Test Stand

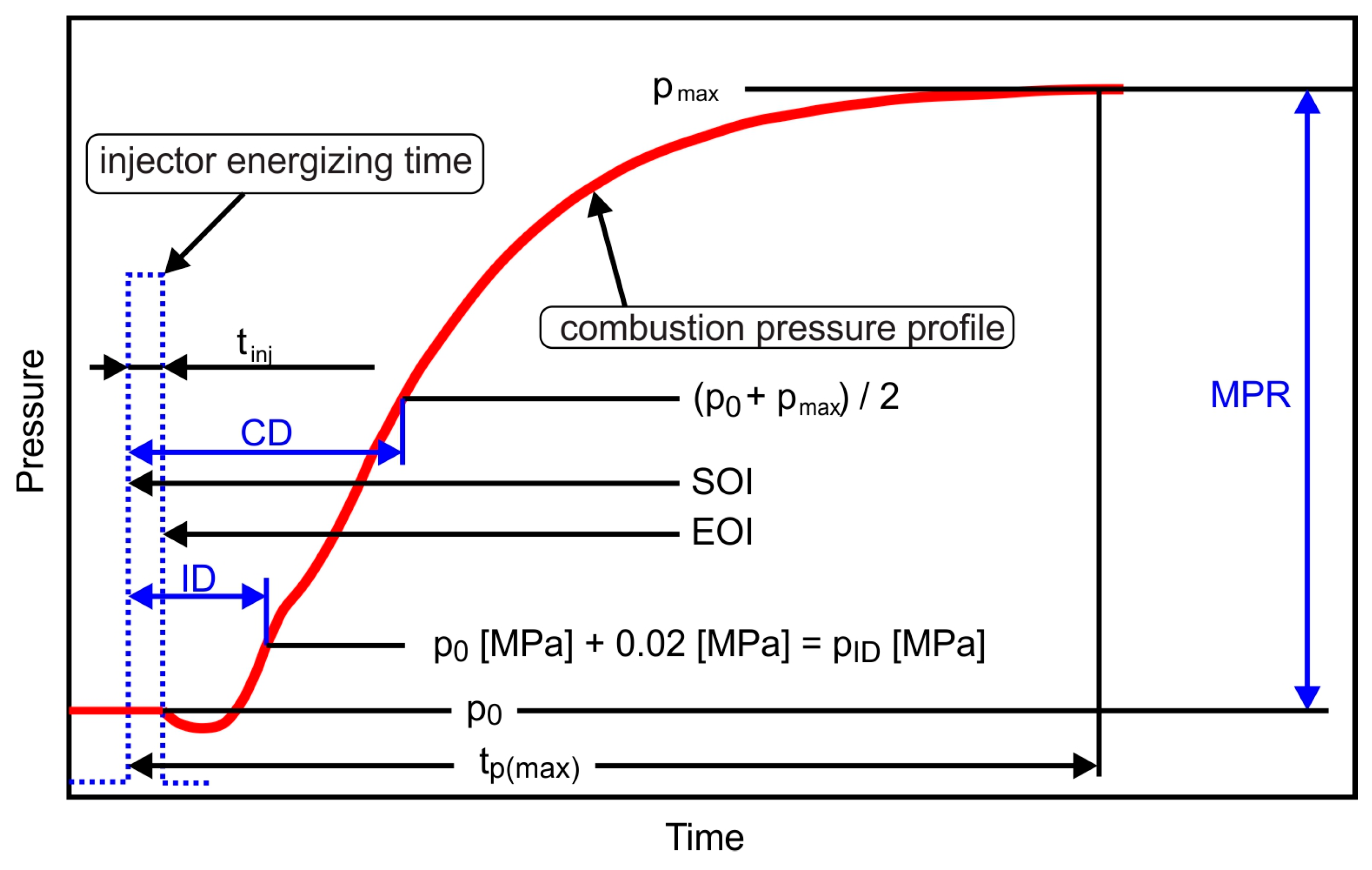

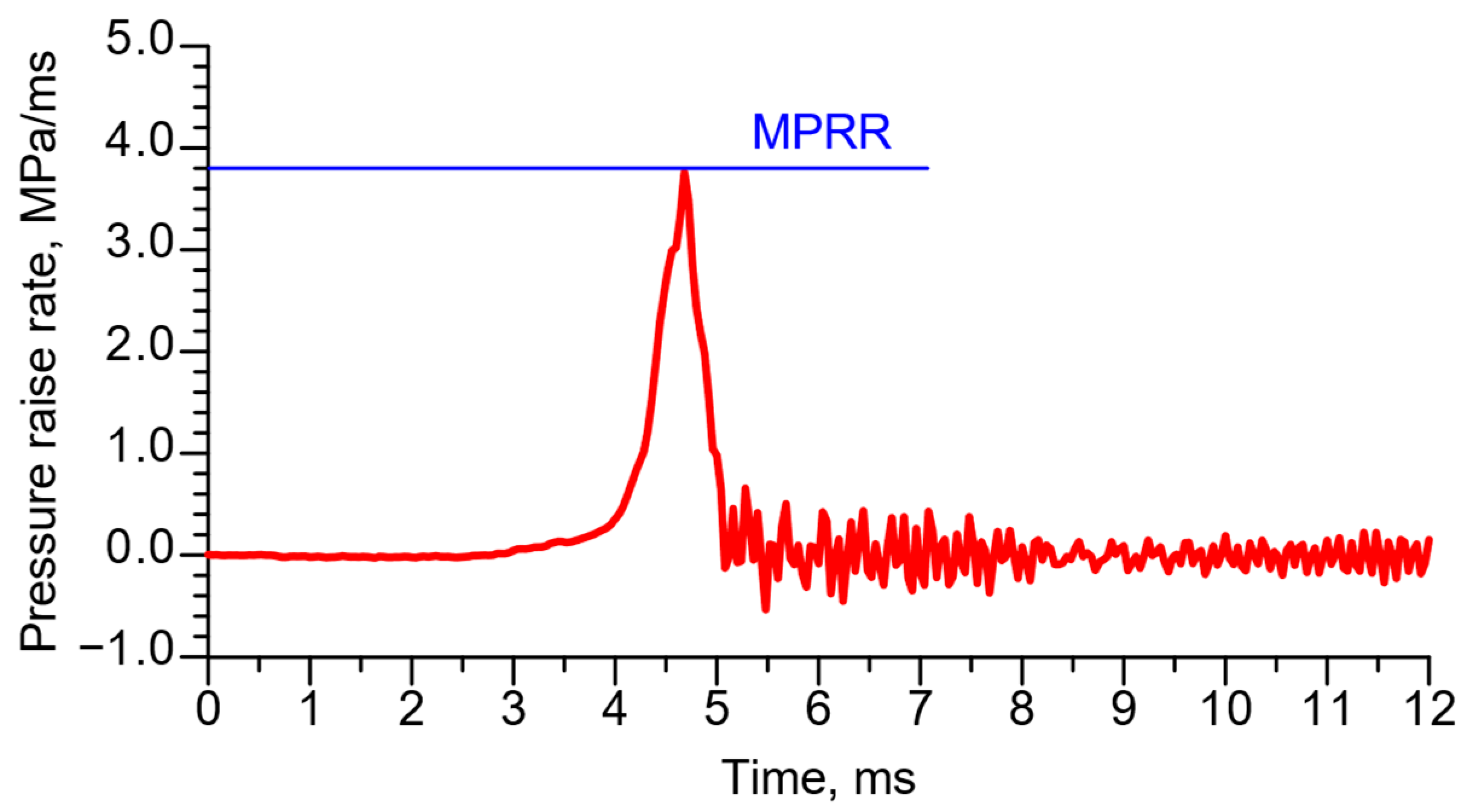

2.3. Research Methodology and Data Acquisition

- pmax—represents the peak pressure value measured during combustion, in MPa;

- pID—pressure value recorded at the conclusion of the ignition delay phase, in MPa;

- tp(max)—denotes the time corresponding to the attainment of pmax, in ms;

- ID—is the ignition delay duration, in ms.

- —denotes the aHRR, in MW;

- V—is the volume of the combustion chamber, which is equal to 473 cm3 (i.e., 0.000473 m3);

- P—indicates the pressure inside the chamber, in Pa;

- t—represents the time at which the pressure is recorded, in ms;

- γ—refers to the ratio of specific heats at constant pressure and volume for the gas mixture (taken as 1.32).

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

4. Conclusions

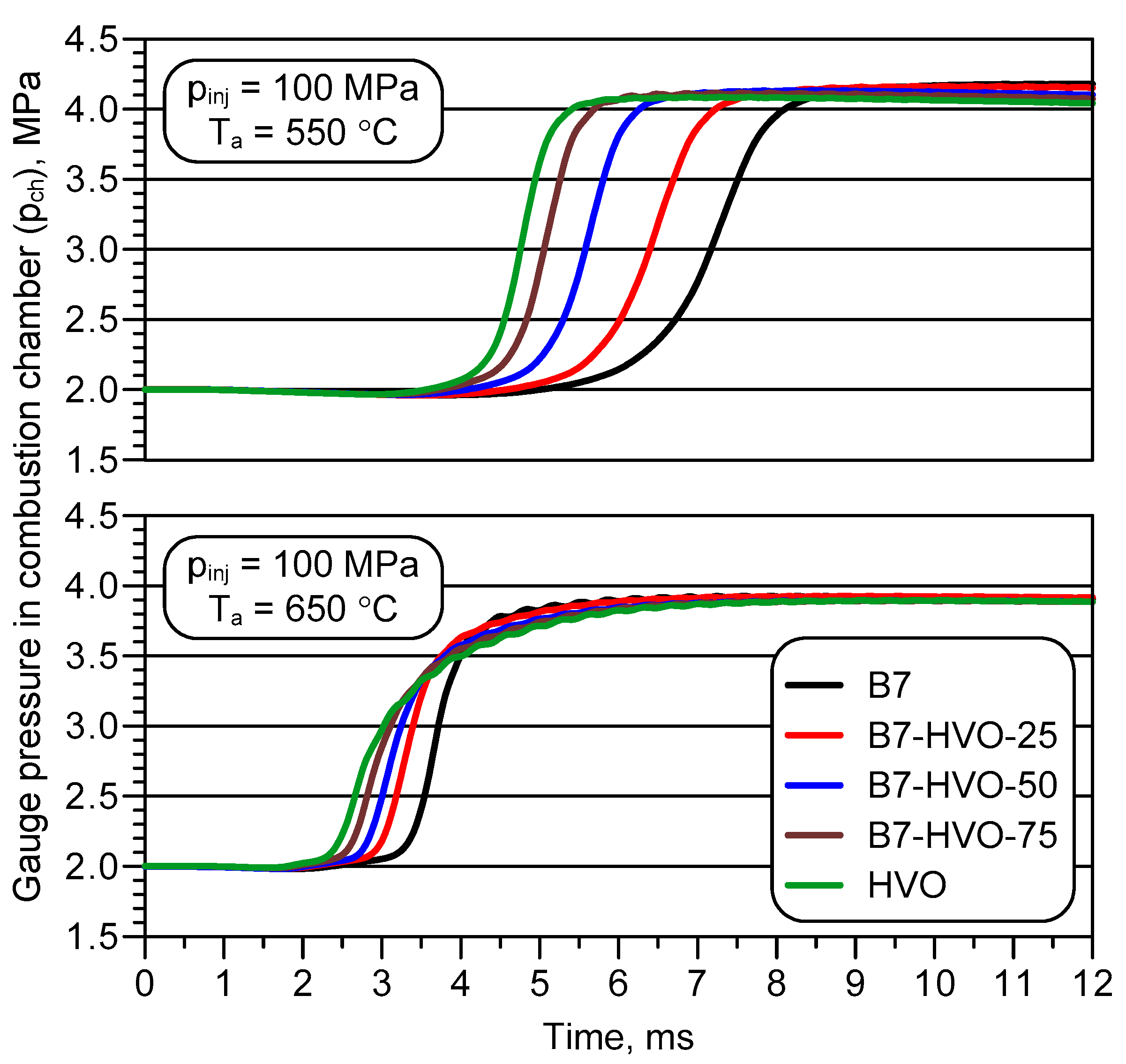

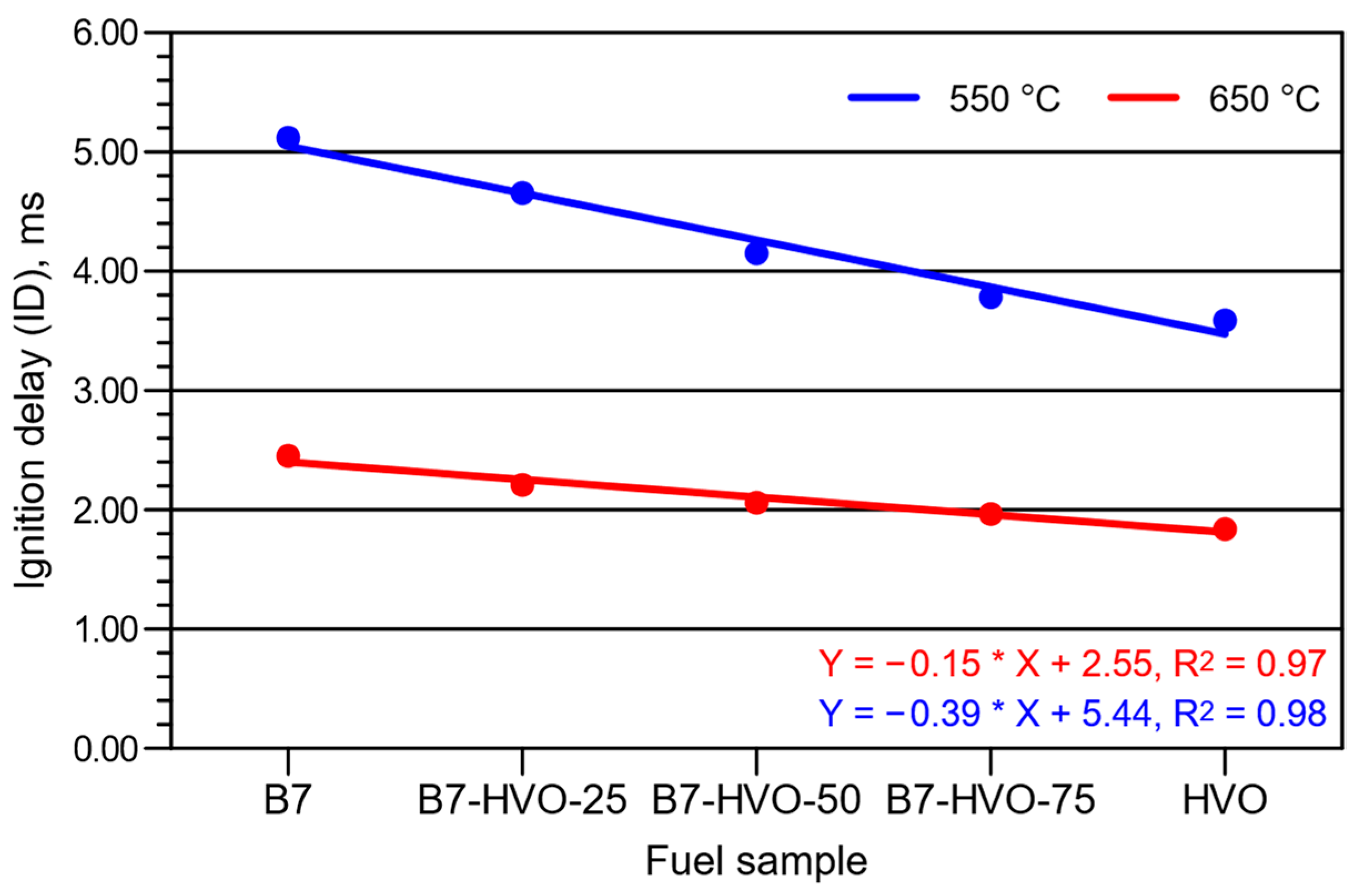

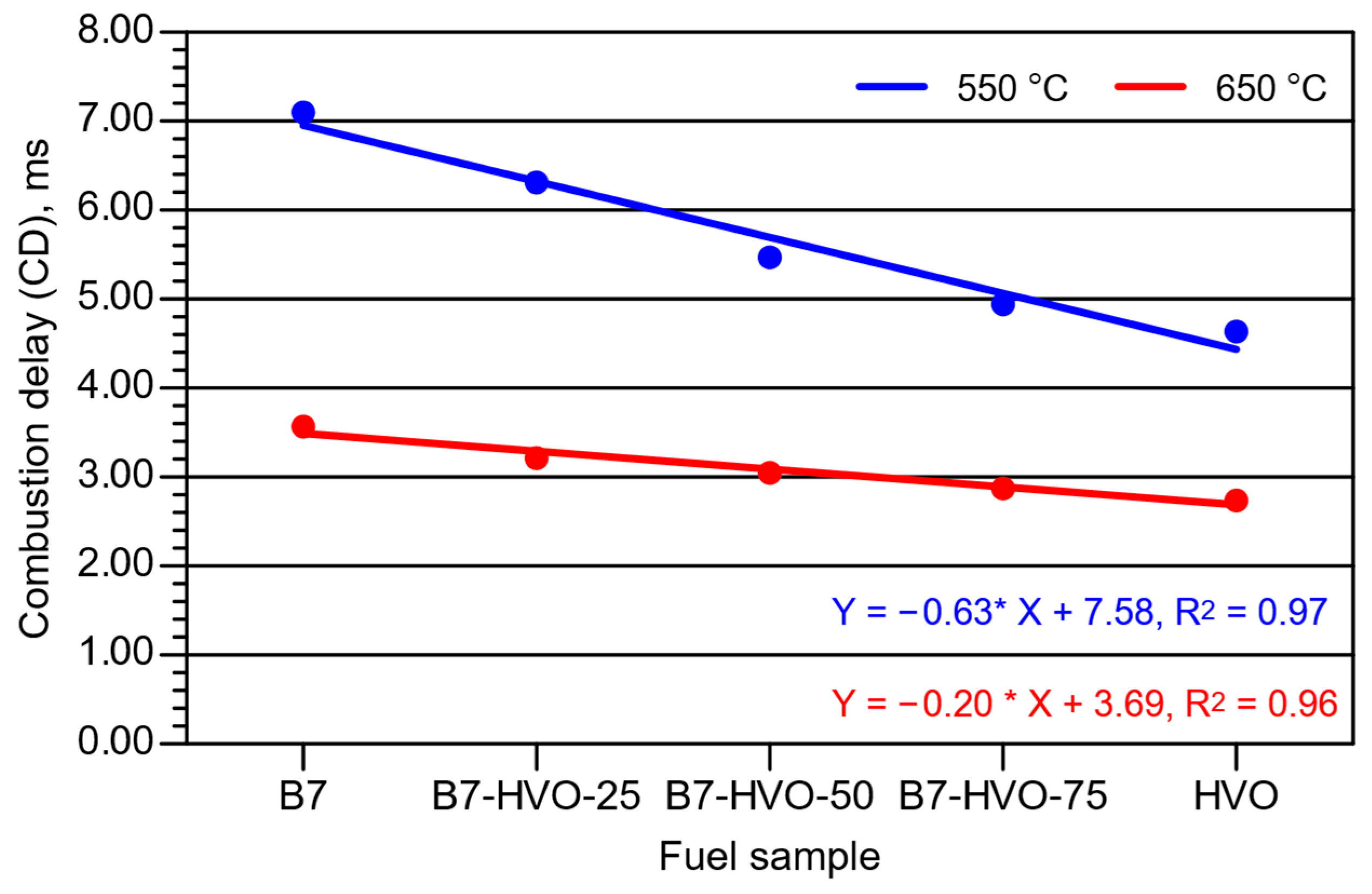

- An increase in the proportion of HVO within the diesel mixture resulted in a clear reduction in ID and CD, although these changes were significantly smaller at the higher initial temperature of the intake air into which the fuel was delivered.

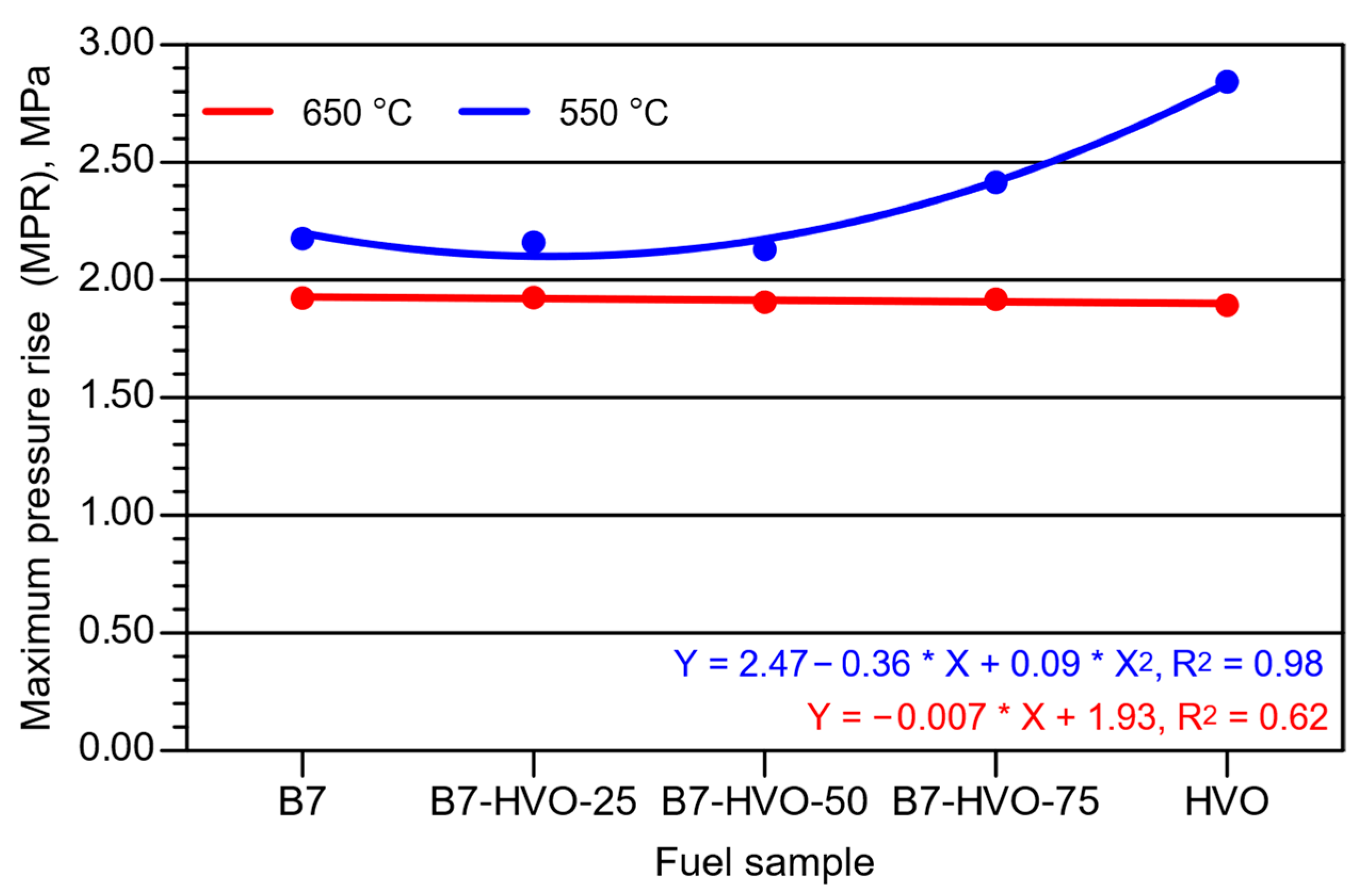

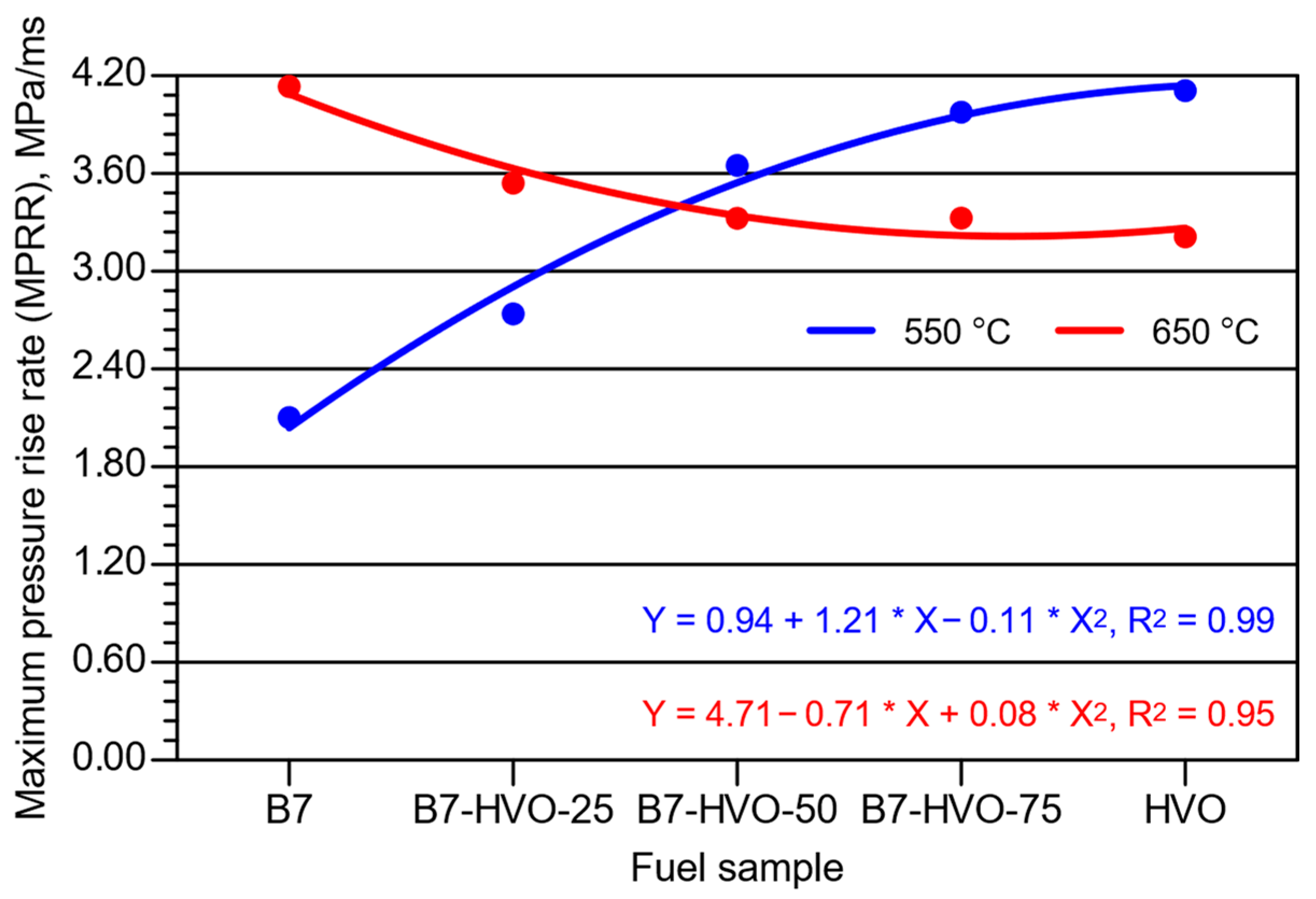

- Increasing the HVO share in the diesel mixture led to a rise in MPR at lower initial combustion chamber air temperature, with the most pronounced changes observed for the 75% HVO blend and neat HVO. At the higher initial chamber temperature, the HVO content in the blend had virtually no effect on the MPR value.

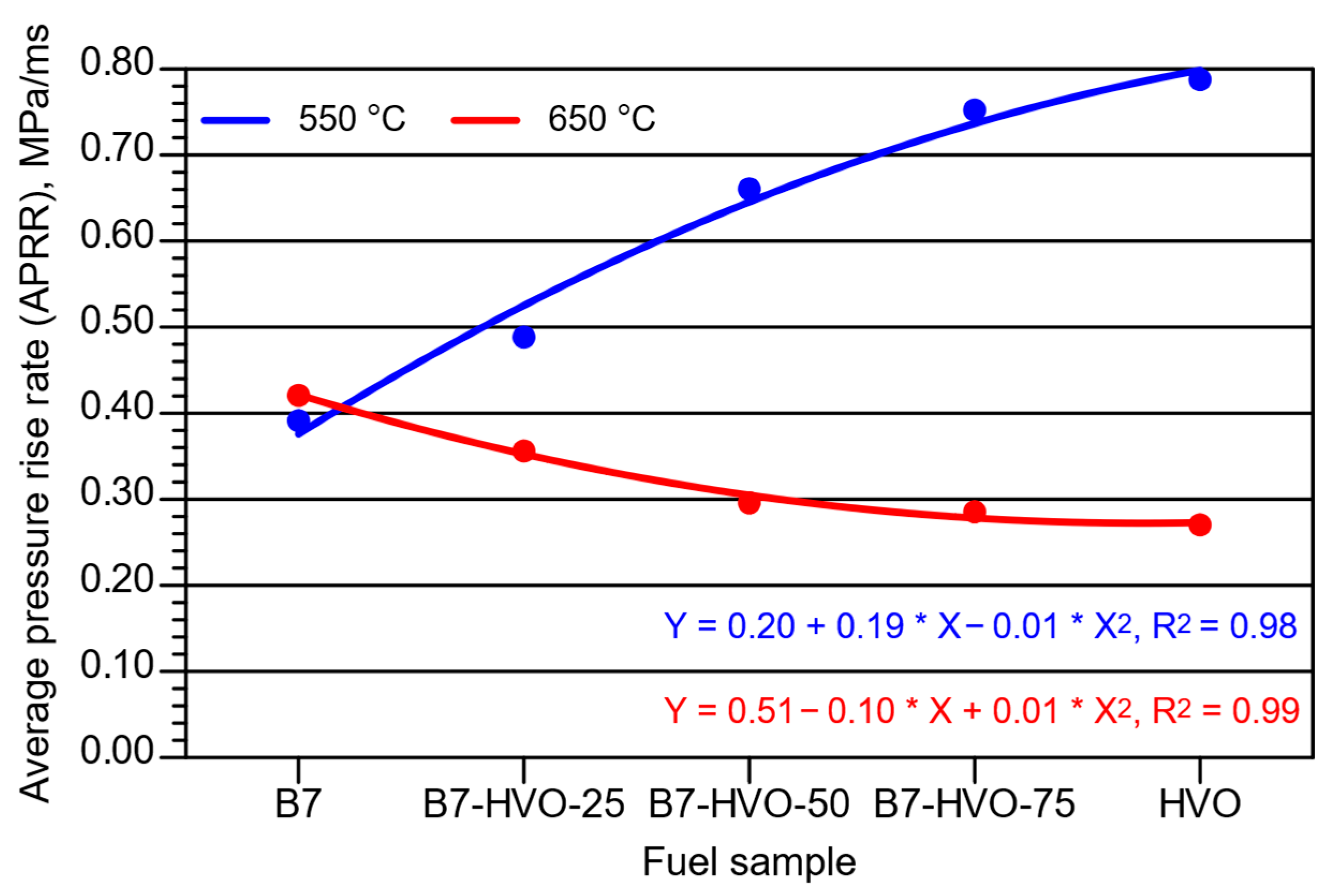

- The APRR parameter increased with rising HVO content at the lower initial combustion chamber temperature. However, at the higher temperature, APRR values were significantly lower and decreased as the HVO content increased. Under engine-like conditions, it may therefore be beneficial to inject fuel into a hotter combustion environment when operating on neat HVO or diesel–HVO fuel mixtures.

- For the MPRR parameter, the trend was consistent with that observed for APRR; however, the differences in absolute values were smaller when comparing the two initial combustion chamber temperatures.

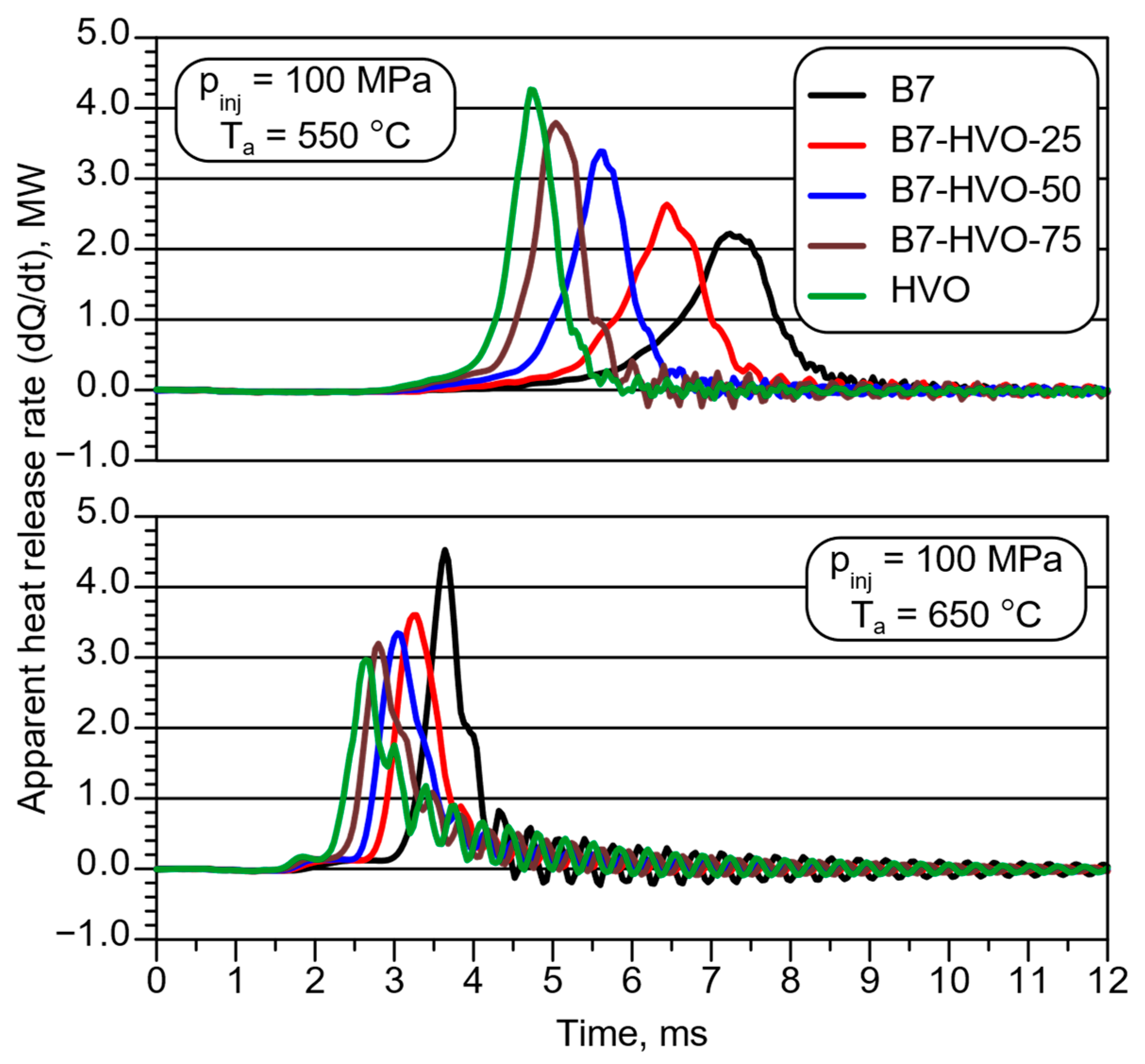

- At the lower of the two analyzed initial combustion chamber temperatures, despite a clear reduction in ID, as the proportion of HVO in the diesel mixture increased, the heat release intensity rose, with the highest peak value observed for neat HVO.

- At the higher initial combustion chamber temperature, the trend in aHRR was reversed; the highest heat release intensity was recorded for neat diesel fuel and decreased as HVO concentration in the blend rose, reaching its lowest value for neat HVO.

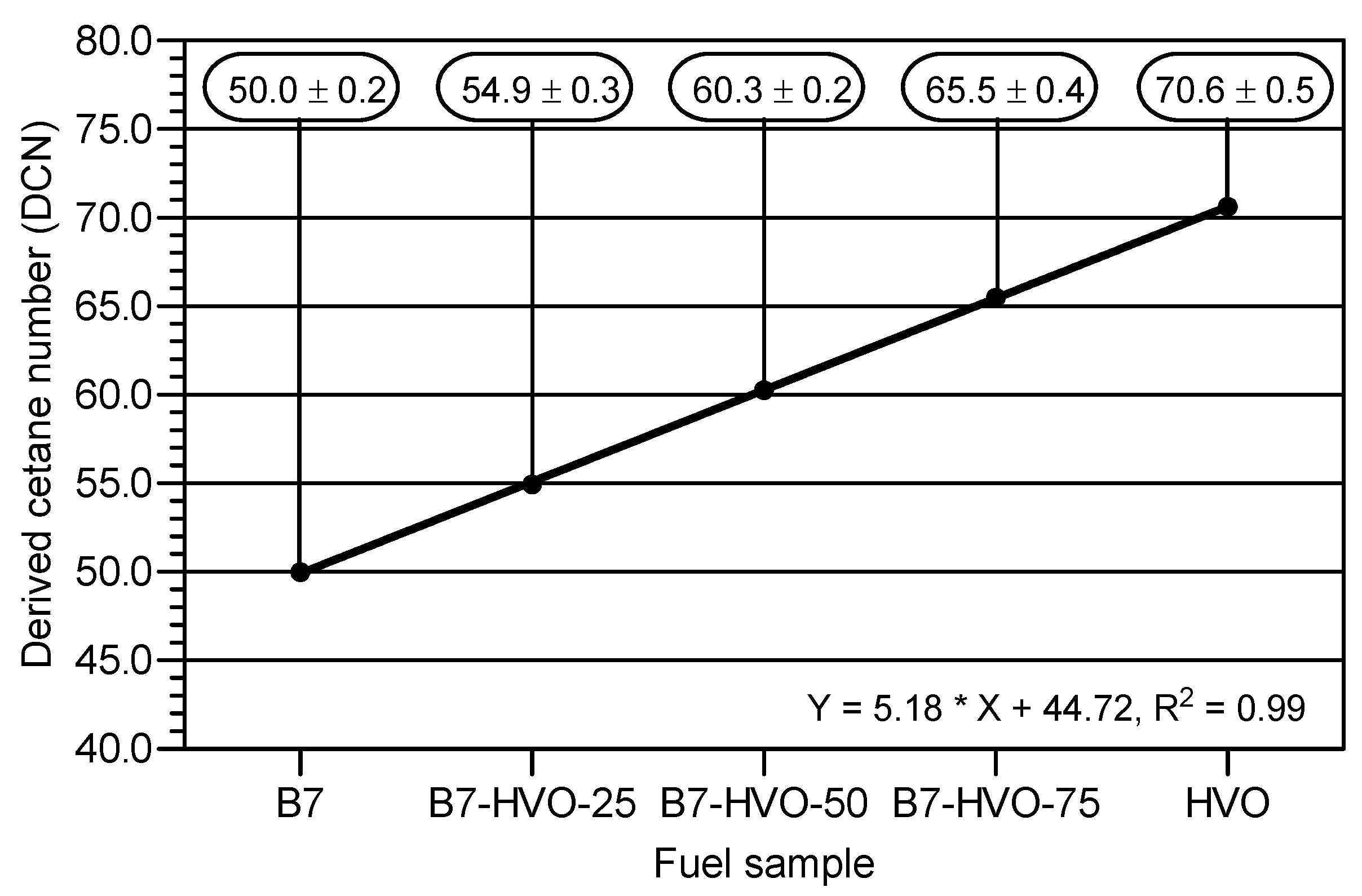

- A higher HVO share in the diesel mixture led to a linear increase in DCN.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HVO | hydrotreated vegetable oil |

| ID | ignition delay |

| CD | combustion delay |

| APRR | average pressure rise rate |

| MPRR | maximum pressure rise rate |

| MPR | maximum pressure rise |

| aHRR | apparent heat release rate |

| NOX | nitrogen oxide |

| CN | cetane number |

| DCN | derived cetane number |

| CVCC | constant volume combustion chamber |

| SOI | start of injection |

| EOI | end of injection |

| ULSD | ultra-low sulfur diesel |

| FAME | fatty acid methyl esters |

| B7 | diesel fuel with up to 7% (v/v) FAME, as per EN 590 |

| 2-EHN | 2-ethylhexyl nitrate |

| HHV | higher heating value |

| WSD | wear scar diameter |

| IBP | initial boiling point |

| FBP | final boiling point |

| SEM | standard error of the mean |

| Ta | initial temperature inside the combustion chamber |

| Tch | chamber wall temperature |

| tinj | injector energized time |

| pinj | injection pressure |

| Tco | injector nozzle coolant jacket temperature |

| Φ | denotes the standard error of the mean associated with the respective parameter |

References

- Abrar, I.; Bhaskarwar, A.N. An overview of current trends and future scope for vegetable oil-based sustainable alternative fuels for compression ignition engines. In Second and Third Generation of Feedstocks: The Evolution of Biofuels; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 531–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonthalia, A.; Kumar, N. Hydroprocessed vegetable oil as a fuel for transportation sector: A review. J. Energy Inst. 2019, 92, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, G.A.A.; Mendes, A.B.; Silva, V.M.D. Decarbonization pathways in Brazilian maritime cabotage: A comparative analysis of very low sulfur fuel oil, marine diesel oil, and hydrogenated vegetable oil in carbon dioxide equivalent emissions. Lat. Am. Transp. Stud. 2024, 2, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbers, T.J.; Sprakel, L.M.J.; van den Enk, L.B.J.; Zaalberg, B.; van den Berg, H.; van der Ham, L.G.J. Green Diesel from Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil Process Design Study. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2015, 38, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzi, G.; Mignini, L.; Venezia, B.; Silva, C.; Santarelli, M. Integration of high-temperature electrolysis in an HVO production process using waste vegetable oil. Energy Procedia 2019, 158, 2005–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, G.W.; O’Connor, P.; Corma, A. Processing biomass in conventional oil refineries: Production of high quality diesel by hydrotreating vegetable oils in heavy vacuum oil mixtures. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2007, 329, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechout, M.; Kotek, M.; Jindra, P.; Macoun, D.; Hart, J.; Vojtisek-Lom, M. Comparison of hydrogenated vegetable oil and biodiesel effects on combustion, unregulated and regulated gaseous pollutants and DPF regeneration procedure in a Euro6 car. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 696, 133748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathurrahman, N.A.; Ginanjar, K.; Devitasari, R.D.; Maslahat, M.; Anggarani, R.; Aisyah, L.; Soemanto, A.; Solikhah, M.D.; Thahar, A.; Wibowo, E.; et al. Long-term storage stability of incorporated hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO) in biodiesel-diesel blends at highland and coastal areas. Fuel Commun. 2024, 18, 100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohl, T.; Smallbone, A.; Tian, G.; Roskilly, A.P. Particulate number and NOx trade-off comparisons between HVO and mineral diesel in HD applications. Fuel 2018, 215, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortel, I.; Vávra, J.; Takáts, M. Effect of HVO fuel mixtures on emissions and performance of a passenger car size diesel engine. Renew. Energy 2019, 140, 680–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajeeb, W.; Gomes, D.M.; Neto, R.C.; Baptista, P. Life cycle analysis of hydrotreated vegetable oils production based on green hydrogen and used cooking oils. Fuel 2025, 390, 134749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Bertoa, R.; Kousoulidou, M.; Clairotte, M.; Giechaskiel, B.; Nuottimäki, J.; Sarjovaara, T.; Lonza, L. Impact of HVO blends on modern diesel passenger cars emissions during real world operation. Fuel 2019, 235, 1427–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihlovec, F.; Vrtiška, D.; Šimáček, P. The use of multivariate statistics and mathematically modeled IR spectra for determination of HVO content in diesel blends. Fuel 2025, 379, 132963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNE EN 15940:2024; Automotive Fuels—Paraffinic Diesel Fuel from Synthesis or Hydrotreatment—Requirements and Test Methods. Available online: https://www.en-standard.eu/une-en-15940-2024-automotive-fuels-paraffinic-diesel-fuel-from-synthesis-or-hydrotreatment-requirements-and-test-methods/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Aligrot, C.; Champoussin, J.C.; Guerrassi, N.; Claus, G. A Correlative Model to Predict Autoignition Delay of Diesel Fuels; SAE Technical Papers; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhaidhawi, M.; Miron, L.; Chiriac, R.; Badescu, V. Autoignition Process in Compression Ignition Engine Fueled by Diesel Fuel and Biodiesel with 20% Rapeseed Biofuel in Diesel Fuel. J. Energy Eng. 2018, 144, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhaidhawi, M.; Chiriac, R.; Badescu, V. Ignition delay, combustion and emission characteristics of Diesel engine fueled with rapeseed biodiesel—A literature review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 73, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, L.; Chiriac, R.; Brabec, M.; Bădescu, V. Ignition delay and its influence on the performance of a Diesel engine operating with different Diesel–biodiesel fuels. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 5483–5494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BS EN 590:2013+A1:2017; Automotive Fuels. Diesel. Requirements and Test Methods. Available online: https://www.en-standard.eu/bs-en-590-2013-a1-2017-automotive-fuels-diesel-requirements-and-test-methods/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- D975; Standard Specification for Diesel Fuel. Available online: https://store.astm.org/d0975-21.html (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- ISO 5165:2020; Petroleum Products—Determination of the Ignition Quality of Diesel Fuels—Cetane Engine Method. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/76906.html (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- D613; Standard Test Method for Cetane Number of Diesel Fuel Oil. Available online: https://store.astm.org/standards/d613 (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Kidoguchi, Y.; Yang, C.; Kato, R.; Miwa, K. Effects of fuel cetane number and aromatics on combustion process and emissions of a direct-injection diesel engine. JSAE Rev. 2000, 21, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, E.; Polonowski, C.J. The Influence of Fuel Cetane Number on Catalyst Light-Off Operation in a Modern Diesel Engine. SAE Int. J. Fuels Lubr. 2017, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataluña, R.; Da Silva, R. Effect of Cetane Number on Specific Fuel Consumption and Particulate Matter and Unburned Hydrocarbon Emissions from Diesel Engines. J. Combust. 2012, 2012, 738940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwuezie, O.C.; Nwakuba, N.R.; Asoegwu, S.N.; Nwaigwe, K.N. Cetane Number Effect on Engine Performance and Gas Emission: A Review. Am. J. Eng. Res. 2017, 6, 56–67. [Google Scholar]

- Reijnders, J.; Boot, M.; de Goey, P. Impact of aromaticity and cetane number on the soot-NOx trade-off in conventional and low temperature combustion. Fuel 2016, 186, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanowitz, J.; Ratcliff, E.M.A.; Mccormick, R.L.; Taylor, J.D.; Battelle, M.J.M. Compendium of Experimental Cetane Numbers. 2014. Available online: www.nrel.gov/publications (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Yates, A.D.B.; Viljoen, C.L.; Swarts, A. Understanding the Relation Between Cetane Number and Combustion Bomb Ignition Delay Measurements; SAE Technical Papers; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, T.W. Correlation of Physical and Chemical Ignition Delay to Cetane Number; SAE Technical Papers; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D6890; Standard Test Method for Determination of Ignition Delay and Derived Cetane Number (DCN) of Diesel Fuel Oils by Combustion in a Constant Volume Chamber. Available online: https://store.astm.org/d6890-21.html (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- UNE EN 15195:2023; Liquid Petroleum Products—Determination of Ignition Delay and Derived Cetane Number (DCN) of Middle Distillate Fuels by Combustion in a Constant Volume Chamber. Available online: https://www.en-standard.eu/une-en-15195-2023-liquid-petroleum-products-determination-of-ignition-delay-and-derived-cetane-number-dcn-of-middle-distillate-fuels-by-combustion-in-a-constant-volume-chamber/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- CSN EN 16144; Liquid Petroleum Products—Determination of Ignition Delay and Derived Cetane Number (DCN) of Middle Distillate Fuels—Fixed Range Injection Period, Constant Volume Combustion Chamber Method. Available online: https://www.en-standard.eu/csn-en-16144-liquid-petroleum-products-determination-of-ignition-delay-and-derived-cetane-number-dcn-of-middle-distillate-fuels-fixed-range-injection-period-constant-volume-combustion-chamber-method/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- BS EN 16715:2015; Liquid Petroleum Products. Determination of Ignition Delay and Derived Cetane Number (DCN) of Middle Distillate Fuels. Ignition Delay and Combustion Delay Determination Using a Constant Volume Combustion Chamber with Direct Fuel Injection. Available online: https://www.en-standard.eu/bs-en-16715-2015-liquid-petroleum-products-determination-of-ignition-delay-and-derived-cetane-number-dcn-of-middle-distillate-fuels-ignition-delay-and-combustion-delay-determination-using-a-constant-volume-combustion-chamber-with-direct-fuel-inj/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- D7668; Standard Test Method for Determination of Derived Cetane Number (DCN) of Diesel Fuel Oils—Ignition Delay and Combustion Delay Using a Constant Volume Combustion Chamber Method. Available online: https://store.astm.org/d7668-17.html (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Kuszewski, H.; Jaworski, A.; Ustrzycki, A.; Lejda, K.; Balawender, K.; Woś, P. Use of the constant volume combustion chamber to examine the properties of autoignition and derived cetane number of mixtures of diesel fuel and ethanol. Fuel 2017, 200, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuszewski, H. Experimental investigation of the effect of ambient gas temperature on the autoignition properties of ethanol–diesel fuel blends. Fuel 2018, 214, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapuerta, M.; Hernández, J.J.; Fernández-Rodríguez, D.; Cova-Bonillo, A. Autoignition of blends of n-butanol and ethanol with diesel or biodiesel fuels in a constant-volume combustion chamber. Energy 2017, 118, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millo, F.; Jafari, M.J.; Piano, A.; Postrioti, L.; Brizi, G.; Vassallo, A.; Pesce, F.; Fittavolini, C. A fundamental study of injection and combustion characteristics of neat Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil (HVO) as a fuel for light-duty diesel engines. Fuel 2025, 379, 132951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørgen, K.O.P.; Emberson, D.R.; Løvås, T. Combustion and soot characteristics of hydrotreated vegetable oil compression-ignited spray flames. Fuel 2020, 266, 116942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunicz, J.; Mikulski, M.; Shukla, P.C.; Gęca, M.S. Partially premixed combustion of hydrotreated vegetable oil in a diesel engine: Sensitivity to boost and exhaust gas recirculation. Fuel 2022, 307, 121910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapuerta, M.; Villajos, M.; Agudelo, J.R.; Boehman, A.L. Key properties and blending strategies of hydrotreated vegetable oil as biofuel for diesel engines. Fuel Process. Technol. 2011, 92, 2406–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, G.; de Souza, T.; da Costa, R.; Roque, L.; Frez, G.; Vidigal, L.; Pérez-Rangel, N.; Coronado, C. Hydrogen and CNG dual-fuel operation of a 6-Cylinder CI engine fueled by HVO and diesel: Emissions, efficiency, and combustion analyses. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 111, 407–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, A.; Seljak, T.; Vihar, R.; Baškovič, U.Ž.; Dimaratos, A.; Bezergianni, S.; Samaras, Z.; Katrašnik, T. Improving PM-NOx trade-off with paraffinic fuels: A study towards diesel engine optimization with HVO. Fuel 2020, 265, 116921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque, L.; da Costa, R.; de Souza, T.; Coronado, C.; Pinto, G.; Cintra, A.; Raats, O.; Oliveira, B.; Frez, G.; Alves, L. Experimental analysis and life cycle assessment of green diesel (HVO) in dual-fuel operation with bioethanol. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 389, 135989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, A.; Schröder, O.; Pabst, C.; Munack, A.; Bünger, J.; Ruck, W.; Krahl, J. Aging studies of biodiesel and HVO and their testing as neat fuel and blends for exhaust emissions in heavy-duty engines and passenger cars. Fuel 2015, 153, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Xu, H.; Shuai, S.-J.; Ghafourian, A.; Liu, D.; Tian, J. Investigation on Transient Emissions of a Turbocharged Diesel Engine Fuelled by HVO Blends. SAE Int. J. Engines 2013, 6, 1046–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bays, J.T.; Gieleciak, R.; Viola, M.B.; Lewis, R.P.; Cort, J.R.; Campbell, K.B.; Coffey, G.W.; Linehan, J.C.; Kusinski, M. Detailed Compositional Comparison of Hydrogenated Vegetable Oil with Several Diesel Fuels and Their Effects on Engine-Out Emissions. SAE Int. J. Fuels Lubr. 2022, 16, 193–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudio, C.; d’Ambrosio, S.; Alessandro, M.; Omar, M.; Nicolò, S. Emissions, Performance and Vibro-Acoustic Analysis of a Compression-Ignition Engine Running on Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil (HVO). In Proceedings of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, Internal Combustion Engine Division (Publication) ICE, San Antonio, TX, USA, 20–23 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kim, S.; Oh, S.; No, S.Y. Engine performance and emission characteristics of hydrotreated vegetable oil in light duty diesel engines. Fuel 2014, 125, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhayat, S.A.; Joshi, G.D.; Henein, N. Analysis and Correlation of Ignition Delay for Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil and Ultra Low Sulfur Diesel and Their Blends in Ignition Quality Tester. Fuel 2021, 289, 119816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, J.J.; Cova-Bonillo, A.; Wu, H.; Barba, J.; Rodríguez-Fernández, J. Low temperature autoignition of diesel fuel under dual operation with hydrogen and hydrogen-carriers. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 258, 115516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuszewski, H.; Jaworski, A. Investigating the Effect of 2-Ethylhexyl Nitrate Cetane Improver (2-EHN) on the Autoignition Characteristics of a 1-Butanol–Diesel Blend. Energies 2024, 17, 4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuszewski, H. Experimental investigation of the autoignition properties of ethanol–biodiesel fuel blends. Fuel 2019, 235, 1301–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soloiu, V.; Wiley, J.T.; Gaubert, R.; Mothershed, D.; Carapia, C.; Smith, R.C.; Williams, J.; Ilie, M.; Rahman, M. Fischer-Tropsch coal-to-liquid fuel negative temperature coefficient region (NTC) and low-temperature heat release (LTHR) in a constant volume combustion chamber (CVCC). Energy 2020, 198, 117288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuszewski, H. Effect of Injection Pressure and Air–Fuel Ratio on the Self-Ignition Properties of 1-Butanol–Diesel Fuel Blends: Study Using a Constant-Volume Combustion Chamber. Energy Fuels 2019, 33, 2335–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, J.J.; Cova-Bonillo, A.; Ramos, A.; Wu, H.; Rodríguez-Fernández, J. Autoignition of sustainable fuels under dual operation with H2-carriers in a constant volume combustion chamber. Fuel 2023, 339, 127487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuszewski, H. Effect of adding 2-ethylhexyl nitrate cetane improver on the autoignition properties of ethanol–diesel fuel blend—Investigation at various ambient gas temperatures. Fuel 2018, 224, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapuerta, M.; Sanz-Argent, J.; Raine, R.R. Ignition Characteristics of Diesel Fuel in a Constant Volume Bomb under Diesel-Like Conditions. Effect of the Operation Parameters. Energy Fuels 2014, 28, 5445–5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Aggarwal, S.K. Two-stage ignition and NTC phenomenon in diesel engines. Fuel 2015, 144, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, E.; Sierens, R. The Physical and the Chemical Part of the Ignition Delay in Diesel Engines; SAE Technical Papers; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeto, W.; Leung, D.Y.C. Is hydrotreated vegetable oil a superior substitute for fossil diesel? A comprehensive review on physicochemical properties, engine performance and emissions. Fuel 2022, 327, 125065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, S.M.; Pritchard, H.O.; Griffiths, J.F. Cetane number vs. structure in paraffin hydrocarbons. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1998, 94, 1725–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbanna, A.M.; Xiaobei, C.; Can, Y.; Elkelawy, M.; Bastawissi, H.A.-E.; Panchal, H. Fuel reactivity controlled compression ignition engine and potential strategies to extend the engine operating range: A comprehensive review. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2022, 13, 100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floweday, G. A New Functional Global Auto-ignition Model for Hydrocarbon Fuels—Part 1 of 2: An Investigation of Fuel Auto-Ignition Behaviour and Existing Global Models. SAE Int. J. Fuels Lubr. 2010, 3, 710–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, H.; Gaffuri, P.; Pitz, W.; Westbrook, C. A Comprehensive Modeling Study of n-Heptane Oxidation. Combust. Flame 1998, 114, 149–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuong, L.S.; Hashimoto, N.; Konno, Y.; Suganuma, Y.; Nomura, H.; Fujita, O. Droplet evaporation characteristics of hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO) under high temperature and pressure conditions. Fuel 2024, 368, 131604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidoguchi, Y.; Nada, Y.; Ichikawa, T.; Miyoshi, H.; Sakai, K. Effect of Pilot Injection on Improvement of Fuel Consumption and Exhaust Emissions of IDI Diesel Engines; SAE Technical Papers; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.J.; Park, B.; Park, J.; Park, S. Effect of pilot injection on engine noise in a single cylinder compression ignition engine. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2015, 16, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.M.; Cho, W.J.; Lee, K.H. Effect of injection condition and swirl on D.I. diesel combustion in a transparent engine system. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2008, 9, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, K.; Nagarajan, G.; Sampath, S. The Effects of Premixed Ratios on the Performance and Emission of PPCCI Combustion in a Single Cylinder Diesel Engine. Int. J. Green. Energy 2013, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worldwide Fuel Charter 2019—Gasoline and Diesel Fuel—ACEA—European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association. Available online: https://www.acea.auto/publication/worldwide-fuel-charter-2019-gasoline-and-diesel-fuel/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

| Measured Property [Unit] | Instrument | Supplier | B7 (Diesel) | HVO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCN | CID 510 | Walter Herzog by PAC, Houston, TX, USA | 50.0 | 70.6 |

| FAME [% (volume)] | OptiFuel | PAC, USA | 6.79 | − |

| O2 [% (mass)] | − | − | 0 a | 0 a |

| H2 [% (mass)] | − | − | 12.86 a | 15.16 a |

| C [% (mass)] | − | − | 87.14 a | 84.84 a |

| Total aromatics [% (mass)] | OptiFuel | PAC, USA | 19.8 | 0 a |

| Polycyclic aromatics [% (mass)] | OptiFuel | PAC, USA | 2.9 | − |

| Tri + aromatics [% (mass)] | OptiFuel | PAC, USA | 0.2 | − |

| Di-aromatics [% (mass)] | OptiFuel | PAC, USA | 2.8 | − |

| Mono [% (mass)] | OptiFuel | PAC, USA | 16.9 | − |

| Paraffins [% (mass)] | − | − | 76.8 b | 100 a |

| Olefins [% (mass)] | − | − | 3.4 a | 0 a |

| 2-EHN [ppm by mass] | OptiFuel | PAC, USA | 0 | - |

| HHV [MJ/kg] | IKA C 5000 | IKA Werke GmbH & Co. KG, Breisgau, Germany | 46.25 | 47.22 |

| Density, 15 °C [g/cm3] | DMA 4500 | Anton Paar GmbH, Graz, Austria | 0.834 | 0.782 |

| Kinematic viscosity, 40 °C [mm2/s] | HVU 472 | Walter Herzog, Lauda-Königshofen, Germany | 2.81 | 2.90 |

| WSD, 60 °C [μm] | PCS HFRR | PCS Instruments, London, UK | 190.5 | 326.0 |

| Water [ppm by mass] | AquaMAX KF | GR Scientific Ltd., Bedford, UK | 38.0 | 17.0 |

| Flash point [°C] | HFP 339 | Walter Herzog by PAC, USA | 63.5 | 64.0 |

| CFPP [°C] | FPP 5Gs | ISL, Paris, France | −21 | −34 |

| IBP [°C] | Optidist | Walter Herzog by PAC, USA | 173.4 | 198.3 |

| Fuel Designation | Volumetric Composition |

|---|---|

| B7 | 100% B7 (standard diesel fuel) |

| B7-HVO-25 | 75% B7, 25% HVO |

| B7-HVO-50 | 50% B7, 50% HVO |

| B7-HVO-75 | 25% B7, 75% HVO |

| HVO | 100% HVO |

| Component | Concentration * |

|---|---|

| N2 (vol. %) | 79.1% ± 0.05% |

| O2 (vol. %) | 20.9% ± 0.05% |

| H2O (ppmv) | <0.5 |

| CO + CO2 (ppmv) | <0.1 |

| THC (ppmv) | <0.05 |

| SO2 (ppmv) | <0.02 |

| NOX (ppmv) | <0.02 |

| Ar (ppmv) | <0.01 |

| Parameter Symbol | Unit | Value | Tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|

| tinj | ms | 2.5 | not defined |

| pinj | MPa | 100.0 | ±1.5 |

| p0 | MPa | 2.00 | ±0.02 |

| Tch | °C | 588.0 | ±0.2 |

| Tco | °C | 50.0 | ±2.0 |

| ΦID [ms] | ΦCD [ms] | ΦAPRR [MPa/ms] | ΦMPRR [MPa/ms] | ΦMPR [MPa] | Tch (Ta) [°C] | p0 [MPa] | pinj [MPa] | tinj [ms] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B7 | 0.0560 | 0.0689 | 0.012 | 0.118 | 0.003 | 550.1 | 2.00 | 99.4 | 2.5 |

| B7-HVO-25 | 0.0383 | 0.0582 | 0.023 | 0.107 | 0.004 | 549.8 | 1.99 | 99.2 | 2.5 |

| B7-HVO-50 | 0.0354 | 0.0484 | 0.043 | 0.269 | 0.001 | 550.3 | 2.00 | 98.9 | 2.5 |

| B7-HVO-75 | 0.0207 | 0.0305 | 0.048 | 0.092 | 0.180 | 540.2 | 2.00 | 99.5 | 2.5 |

| HVO | 0.0328 | 0.0304 | 0.062 | 0.144 | 0.021 | 550.2 | 1.99 | 99.3 | 2.5 |

| ΦID [ms] | ΦCD [ms] | ΦAPRR [MPa/ms] | ΦMPRR [MPa/ms] | ΦMPR [MPa] | Tch (Ta) [°C] | p0 [MPa] | pinj [MPa] | tinj [ms] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B7 | 0.0090 | 0.0109 | 0.012 | 0.132 | 0.005 | 649.6 | 1.99 | 99.6 | 2.5 |

| B7-HVO-25 | 0.0129 | 0.0172 | 0.013 | 0.149 | 0.004 | 649.6 | 1.99 | 100.0 | 2.5 |

| B7-HVO-50 | 0.0118 | 0.0076 | 0.016 | 0.126 | 0.010 | 649.6 | 1.99 | 99.3 | 2.5 |

| B7-HVO-75 | 0.0182 | 0.0149 | 0.012 | 0.208 | 0.017 | 649.9 | 2.00 | 99.3 | 2.5 |

| HVO | 0.0110 | 0.0184 | 0.011 | 0.279 | 0.002 | 649.6 | 2.00 | 99.3 | 2.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuszewski, H.; Jaworski, A.; Szpica, D. Performance of Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil–Diesel Blends: Ignition and Combustion Insights. Energies 2025, 18, 5962. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225962

Kuszewski H, Jaworski A, Szpica D. Performance of Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil–Diesel Blends: Ignition and Combustion Insights. Energies. 2025; 18(22):5962. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225962

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuszewski, Hubert, Artur Jaworski, and Dariusz Szpica. 2025. "Performance of Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil–Diesel Blends: Ignition and Combustion Insights" Energies 18, no. 22: 5962. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225962

APA StyleKuszewski, H., Jaworski, A., & Szpica, D. (2025). Performance of Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil–Diesel Blends: Ignition and Combustion Insights. Energies, 18(22), 5962. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225962