1. Introduction

Particulate matter (PM) emissions that comprise a complex mixture of microscopic particles are an important deteriorating factor in human health and air quality [

1,

2]. Internationally, the transport sector alone contributes nearly 15% of total greenhouse gas emissions. In the European Union specifically, road transport is the largest contributor to particle emissions. It accounts for almost 60% of PM10 (particles with a diameter ≤ 10 μm) emissions and 45% of PM2.5 (particles with a diameter ≤ 2.5 μm) emissions [

3,

4,

5]. The significant threat of particulate pollution that leads to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases has prompted countries around the world to implement strategies to reduce pollution and improve air quality [

6,

7,

8].

Among all after-treatment methods, particulate filters are considered the most effective due to their simple nature and have been widely used in commercial vehicles [

2,

9,

10]. These filters capture tiny particles that are released from the exhaust in the form of airborne pollutants. Conventional diesel particulate filters use a honeycomb structure of ceramic-coated channels that block the particles and allow the gases to flow from one channel to another. To maintain engine performance, filtered soot, which is deposited on the walls, is regularly burnt and turned into ash before the filter becomes clogged [

11].

Conventional particulate filters are typically designed to trap particles in the range of 5 to 100 μm in size. However, the actual size range that a particulate filter can effectively trap can vary depending on the type of filter and the specific design features of the filter media [

11]. Course particles or PM10 can be easily filtered through conventional filters with a collecting efficiency of 99%, but with a decrease in the size of the particles, the efficiency decreases. Some fine particles or PM2.5 escape through the filters and are released into the atmosphere, raising concerns for health and pollution [

12].

If we restrict smaller fine particles, the size of the pores in the filter is decreased and the soot accumulates over time and might cause filter clogging. This increases the exhaust back pressure of the engine, leading to poor efficiency and fuel economy performance [

13,

14]. To counteract this issue, various research projects have focused on the idea of agglomerating smaller particles to form larger particles, which makes it easier to filter through conventional filters. The use of acoustic or sound waves to facilitate the process of agglomeration is called acoustic agglomeration (AA) [

15]. The kinetic energy of the particles increases when they are subjected to acoustic waves. This increase in kinetic energy increases the excitation of the particles and makes them move rapidly across the chamber. This rapid movement within the chamber increases the chances of collisions between the particles. As a result of the chemical composition of the particles and their sticky nature, the particles become agglomerated and thereby increase in size. In particular, fine particles with their small size and mass excite with higher energy, increasing their chances of agglomeration.

Since the concept was first observed in 1931 [

16], various researchers around the world have been successful in showing the potential of AA in capturing small particles that are difficult to capture conventionally. The results showed that with an application of certain controlled sound pressure levels, particles greater than the size range of 2–10 μm increase with a decrease in PM2.5 particles. This proved that, with an application of sound waves, smaller particles agglomerate to form large-sized particles [

17,

18,

19,

20]. There are various parameters that influence the agglomeration efficiency like temperature, viscosity, density, composition, and especially humidity matter. Higher relative humidity and short bursts of heterogeneous condensation (supersaturation) reportedly improve sticking which encourages agglomeration [

21].

In addition to the after-treatment methods, focus is also placed on the pretreatment method to reduce exhaust emissions. Using alternative fuels and fuel additives comes under the category of pretreatment. It has many advantages that involve environmental, economic, and technical aspects [

22,

23]. These benefits contribute to a sustainable and clean-energy world. Alternative fuels, which are derived from renewable sources, often exhibit lower emissions compared to diesel fuel, leading to an improvement in air quality and health conditions [

24,

25,

26]. They are sustainable and require the least modifications to existing combustion engines [

27,

28]. There is still a gap in the practical application of the concept of acoustic agglomeration on particle emissions.

Rapeseed methyl ester, or RME, is a biodiesel produced in the transesterification process of renewable rapeseed oil. Currently, RME is the most important biofuel produced in the European market under FAME (fatty acid methyl esters). FAME can also be produced from non-food and waste-based sources such as used cooking oil or animal fats. The scale of production and consumption of this fuel is expected to continue to increase due to the growing demand for diesel fuels [

29,

30,

31]. To reduce the solidification complications associated with biodiesel, they are often blended with an oxygen-rich alternative. Blending biodiesels and alcohols has been found to be a great way to reduce particulate emissions by more than 20% while maintaining the efficiency of a diesel engine [

32,

33]. The fuel used for testing is produced in Lithuania and is as per the EN 14214 [

34] quality standard [

35].

Isopropanol, on the other hand, is a fuel additive that acts as an oxygenate that improves combustion efficiency [

36,

37]. The oxygen present in the alcohol leads to more complete combustion and thus reduces the formation of particulate matter [

23]. The implications of oxygen and C/H ratio on fine particle emissions is an area of particular interest that can be further studied.

Although major research has been conducted on the implications of acoustic agglomeration, there is still a gap in the application of the concept on exhaust particle emissions. This research particularly aims to reduce the fine particle emissions by focusing on experimentally determining the combined advantage of reducing particle emissions by using different alternative fuel blends along with the implementation of the concept of acoustic agglomeration by using an in-house-built acoustic chamber.

2. Materials and Methods

The primary testing equipment used is a 1.9 turbocharged direct injection diesel engine with a BOSCH VP37 (Bosch, Gerlingen, Germany) electronically controlled distribution fuel pump. It is a 4-cylinder engine working on a single injection strategy and the injection timing is controlled by the Electronic Control Unit (ECU). Engine displacement: 1.896 L; maximum power: 66 kW at 4000 rpm; peak torque: 180 Nm at 2000–2500 rpm. Detailed parameters of the engine tested are presented in some of the previous studies [

38,

39].

The fuels used for the testing are pure diesel fuel (D100) and rapeseed methyl ester (RME100), as well as two RME–isopropanol blends were formulated: 90 vol.% RME/10 vol.% isopropanol (RME90IP10) and 95 vol.% RME/5 vol.% isopropanol (RME95IP5). Selected properties (see the below of the chapter) were obtained by converting volumetric fractions to mass fractions and then applying mass-fraction weighting of the component properties.

where

mi—mass fraction of component

i;

vi—volumetric (volume) fraction of component

i; and

ρi—density of component

i.

Replacing fossil diesel with renewable alternatives—RME and its blends with isopropanol—modifies the physicochemical properties of the fuel. The engine used in this study is calibrated for conventional fossil diesel or EN 590 [

40] diesel containing up to 7 vol.% FAME; therefore, operation on the investigated RME–isopropanol blends warrants further work to optimize hardware and calibration, including the compression ratio, start of fuel injection, and other adaptive subsystems, to ensure proper matching to fuel quality. Lubricity is also a pertinent concern, as alcohol addition may degrade lubricating performance; dedicated lubricity evaluations should thus be carried out.

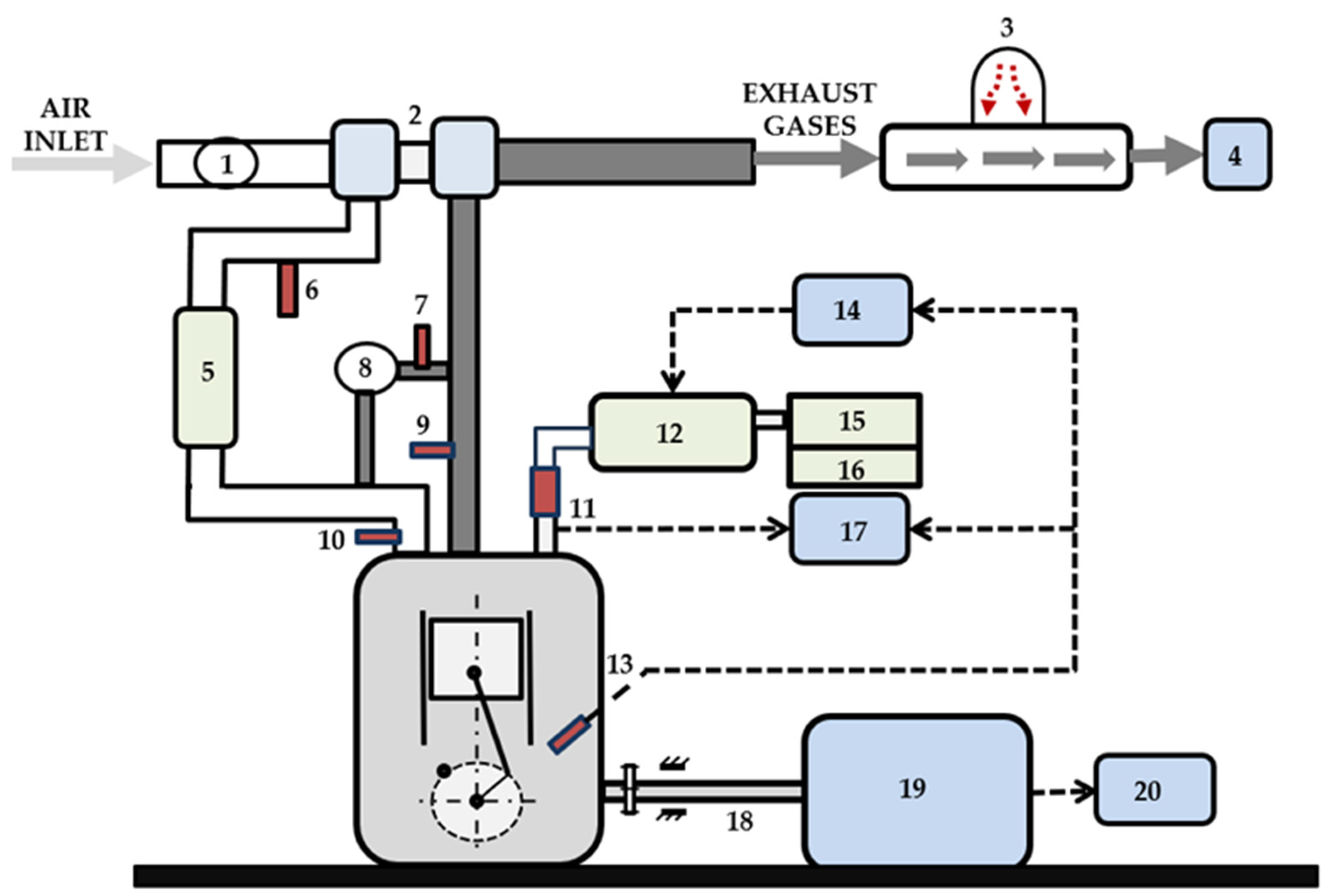

The TDI engine runs on the tested fuels, and the exhaust is connected to the acoustic chamber; the agglomeration is recorded after the exhaust gas is passed through the chamber, where it is naturally cooled, and is further studied. Tests are carried out at two different loads—90 Nm and 60 Nm (

BMEP = 0.6 MPa and 0.4 MPa, respectively)—at an engine speed

n = 2000 rpm. A portion of the exhaust gases is fed into the acoustic chamber. The schematic diagram of the test bench is presented in

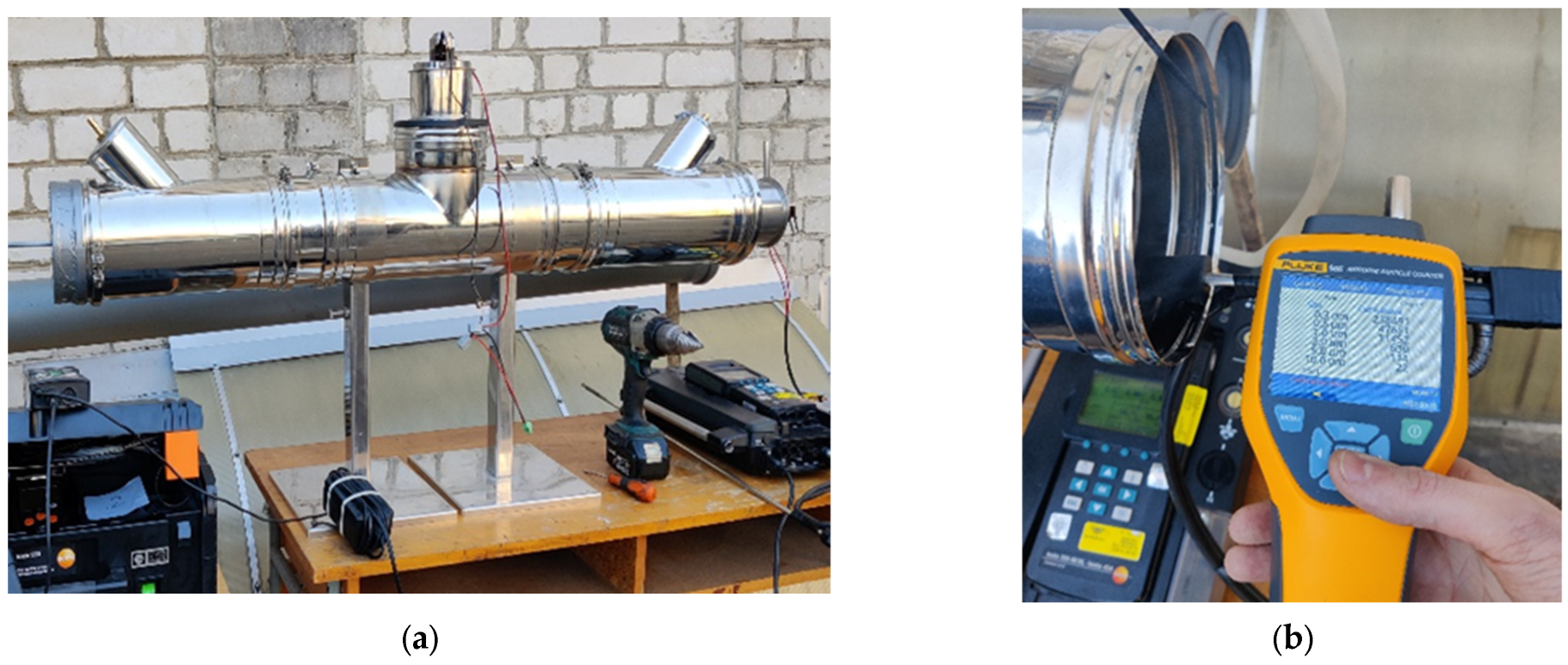

Figure 1. The acoustic chamber was specifically designed by the researchers of Vilnius Tech to study the agglomeration of the particles in the presence of sound waves. The setup consists of longitudinal and angular chambers where the agglomeration takes place, as presented in

Figure 2a. It is connected with a piezoelectric excitation source controlled through a PC and PDUS210 ultrasonic driver (Precision Acoustics Ltd., Dorchester, UK). The sound pressure of the acoustic chamber is maintained at 140 dB, a frequency of 19 kHz, and an agglomerator voltage of 100 V throughout the experimentation, which is obtained based on the previous research results that achieved agglomeration through acoustics. The exhaust gases are channeled through one end of the longitudinal chamber, and the particles are measured on the opposite end after passing through the excitation source as presented in

Figure 2b. Each reading is measured for a period of 60 s, and the average reading is taken after three repetitions. The ambient temperature of 21 degrees and a humidity of 45% is maintained throughout the experiment.

A 6 channel Fluke 985 particle counter (Fluke Corporation, Everett, WA, USA) (presented in

Figure 2b) with a large 3.5 QVGC color display was used to accurately measure the particles in 6 channels of 0.3, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, and 10 μm. The operating condition is <95% relative humidity without condensation, and the temperature is 10–40 degrees Celsius. The sample inlet for precision isokinetic probe was used. To calibrate and prevent residual values, the zero-reading scale was checked with a zero filter before each test. The residual level did not exceed one count in 5 min for particles of 0.3 μm in size (based on JIS B9921 [

41]).

The flow rate is 0.1 cfm (2.83 L/min), which refers to the gas volume drawn in per unit time. The diameter of the entire system duct section is 150 mm. It utilizes a 90 mW class 3B laser as the light source at 775 to 795 nm. The concentration limits are 10% at 4,000,000 particles per ft3 (per ISO 21501 [

42]). The counting efficiency of the Fluke 985 particle counter is 50% for particles of a 0.3 μm size and 100% for particles of a size greater than 0.45 μm. The counting efficiency is as per ISO 21501.

3. Results

The fuel blends, D100, RME95I5 and RME90I10, are tested at lower (60 Nm) and higher (90 Nm) loads. Part of exhaust gas emissions are then sent to the in-house built acoustic chamber, where a sound pressure level of 140 dB and frequency of 19 kHz are maintained. The particles are measured in six different sizes between the range of 0.3–10 μm based on a total sampled air volume of 1.42 L aspirated through the instrument.

The change in particle number with acoustics at all conditions is calculated using the formula:

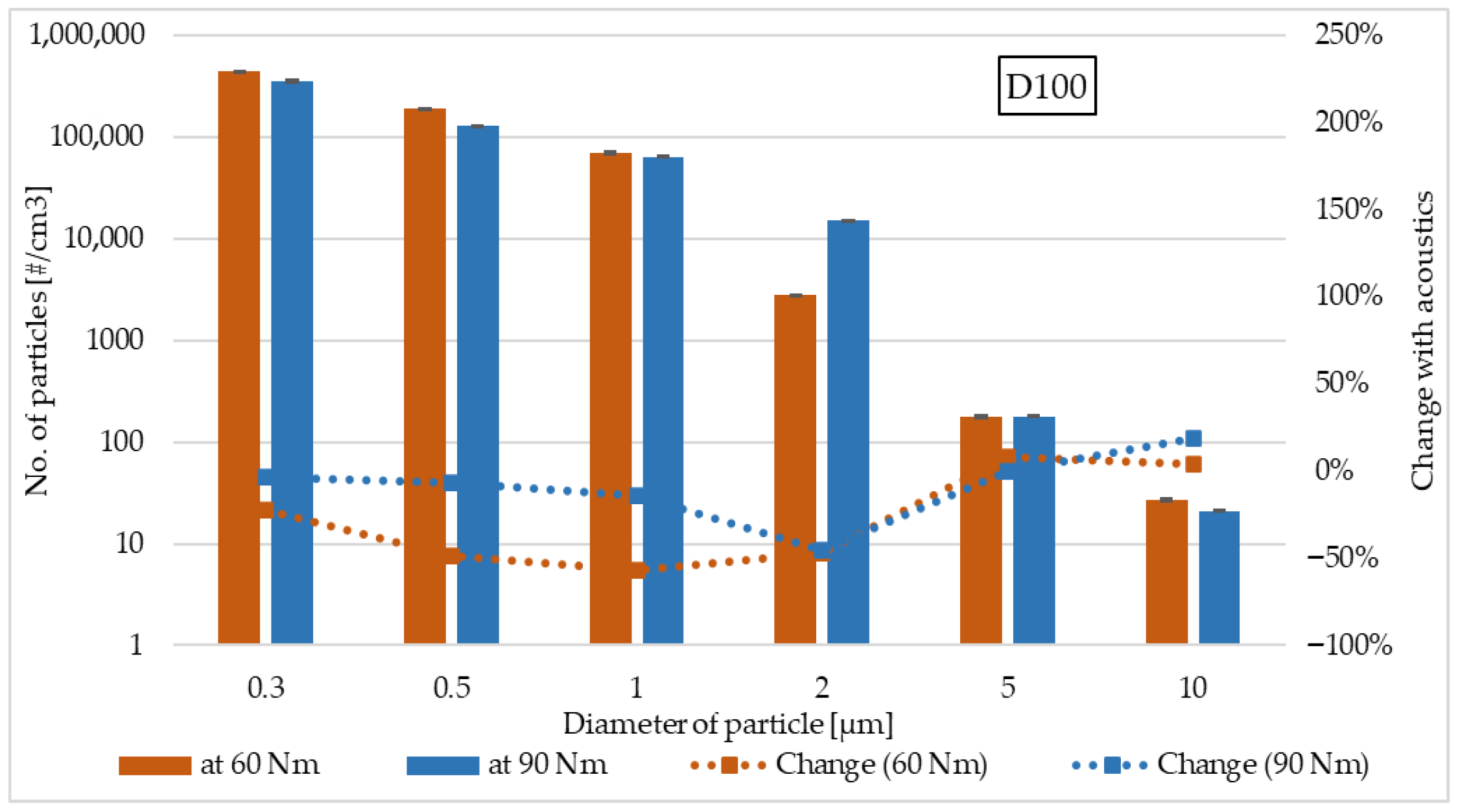

Under all tested conditions, as expected, diesel (D100) has higher particle emissions compared to biodiesel blends (as presented in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) [

23]. At lower load, fine particle emissions are relatively higher and with an increase in load from 60 Nm to 90 Nm, 2 μm-sized particles are found to increase in the case of D100 (shown in

Figure 3). This can be due to the incomplete combustion of fuel and low temperatures. The soot formed due to the bad mixing conditions usually comprises small fragments of particles. When there is no acoustic presence, with increasing load, particles of a 2 μm size are increased by 4.4 times.

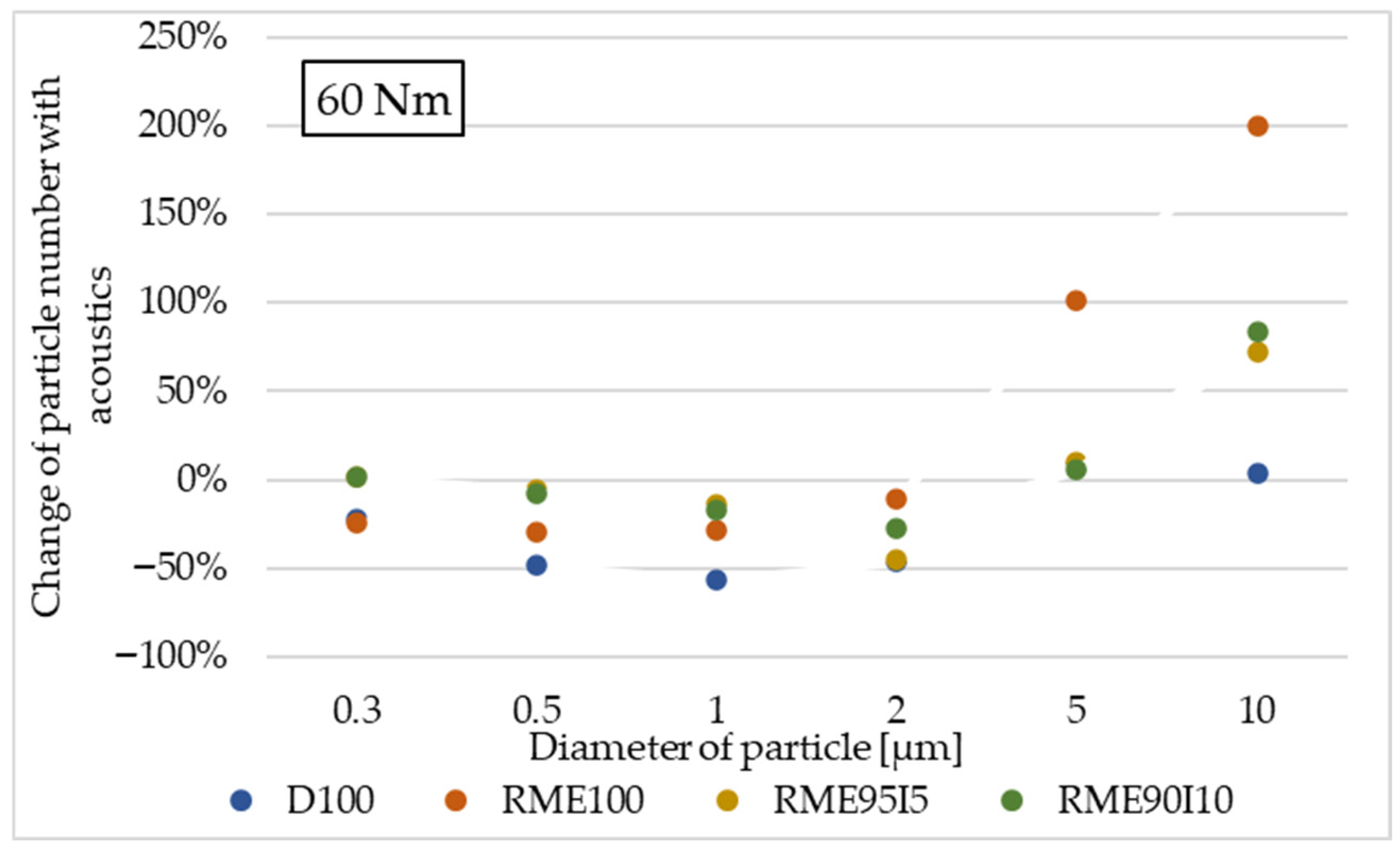

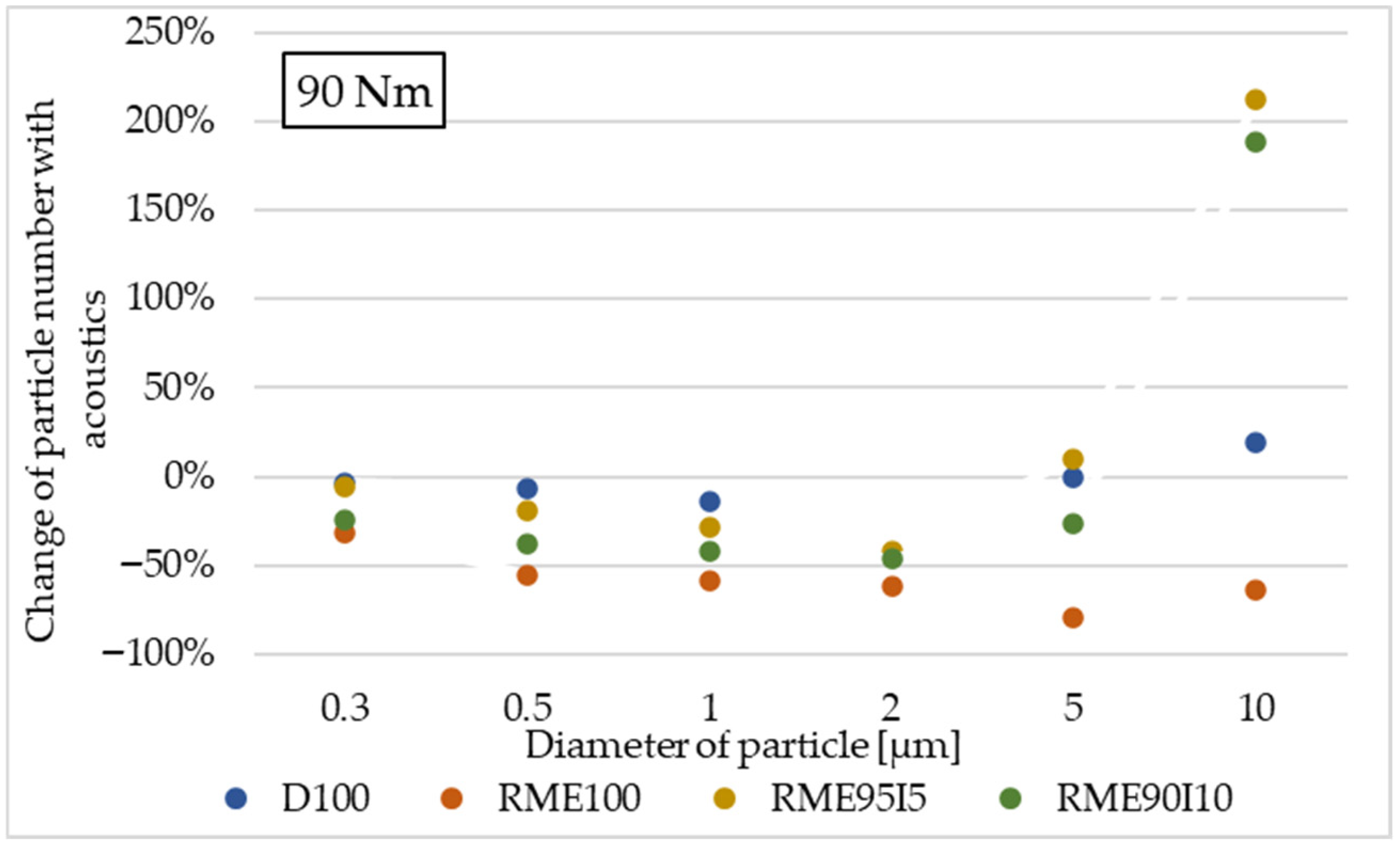

It is also found that with the presence of acoustic waves, there is a steady decrease in fine particles or PM2.5 and an increase in particles of a 5 and 10 μm size at both loads, which means that smaller particles are agglomerated to form large particles. At 60 Nm, the maximum reduction in fine particles is recorded (average of 44% of particles sized between 0.3 and 2 μm) and the increase in large-size particles was 6% (average of particles of a 5 and 10 μm size). At high loads, the reduction in fine particles decreased to an average of 17% but, interestingly, the large-sized particles are increased to 10%. These results are in line with those obtained using a similar acoustic setup [

43].

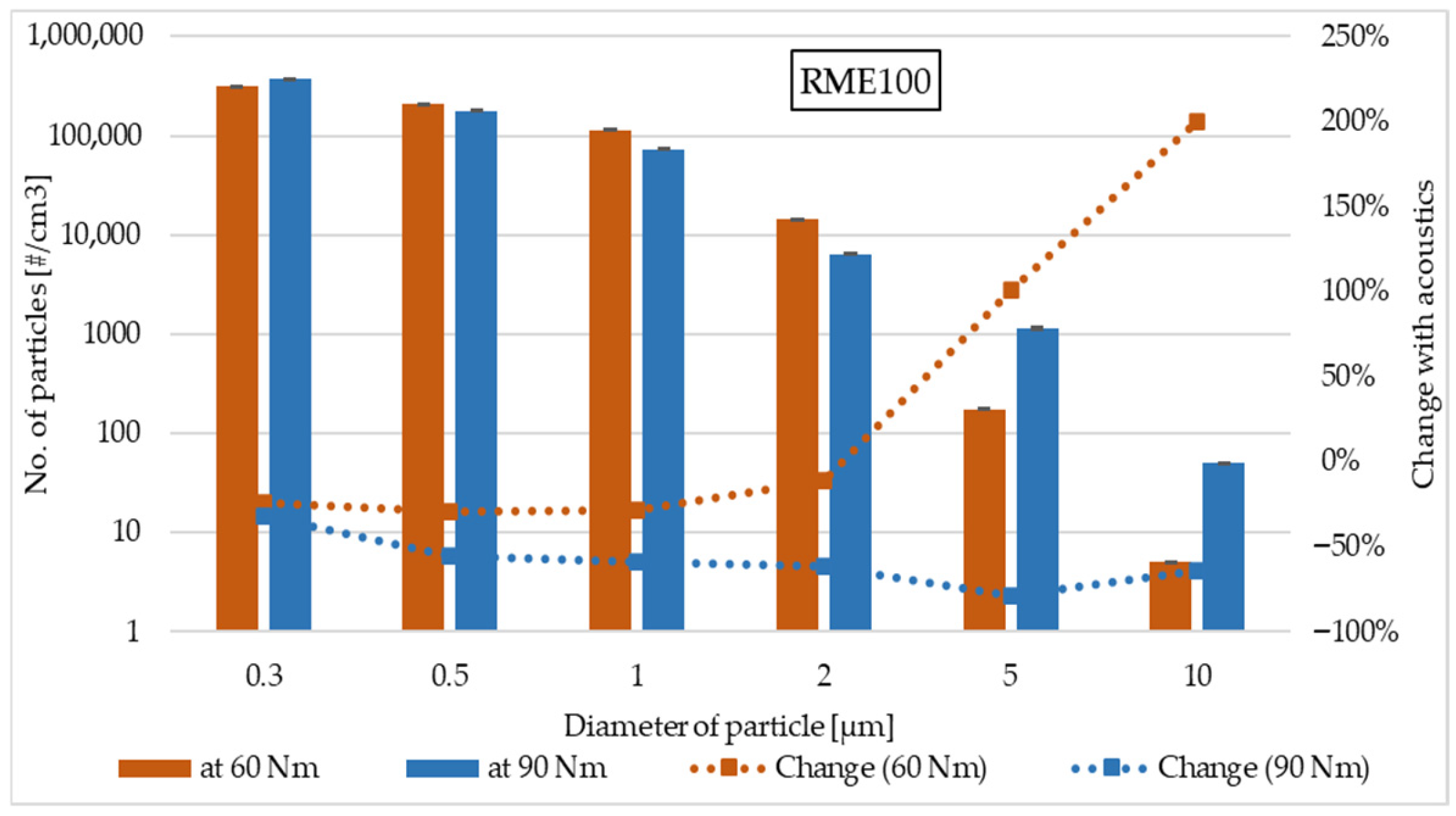

Compared with diesel, biodiesel has been found to produce less overall particle emissions. This observed trend is attributed to the 10% reduction in carbon content and the presence of oxygen (presented in

Table 1), which promotes clean and complete combustion, thereby producing fewer emissions [

22,

23]. For RME100, with an increase in load from 60 to 90 Nm, 0.5–2 μm-sized particles are consistently decreasing with a significant increase in large-diameter particles as shown in

Figure 4.

An average reduction of 35% is observed in fine particles, with 2 μm particles being the highest at 55%. At lower load, a 100% increase in 5 μm-sized particles is recorded along with a 200% increase in 10 μm particles. A slight reduction can also be found for fine particles. With an increase in load from 60 to 90 Nm and with the presence of acoustic excitation, an overall reduction in particles is found at all tested sizes. Consistent with the trend observed for diesel fuel, fine particles are found to decrease with an increase in load.

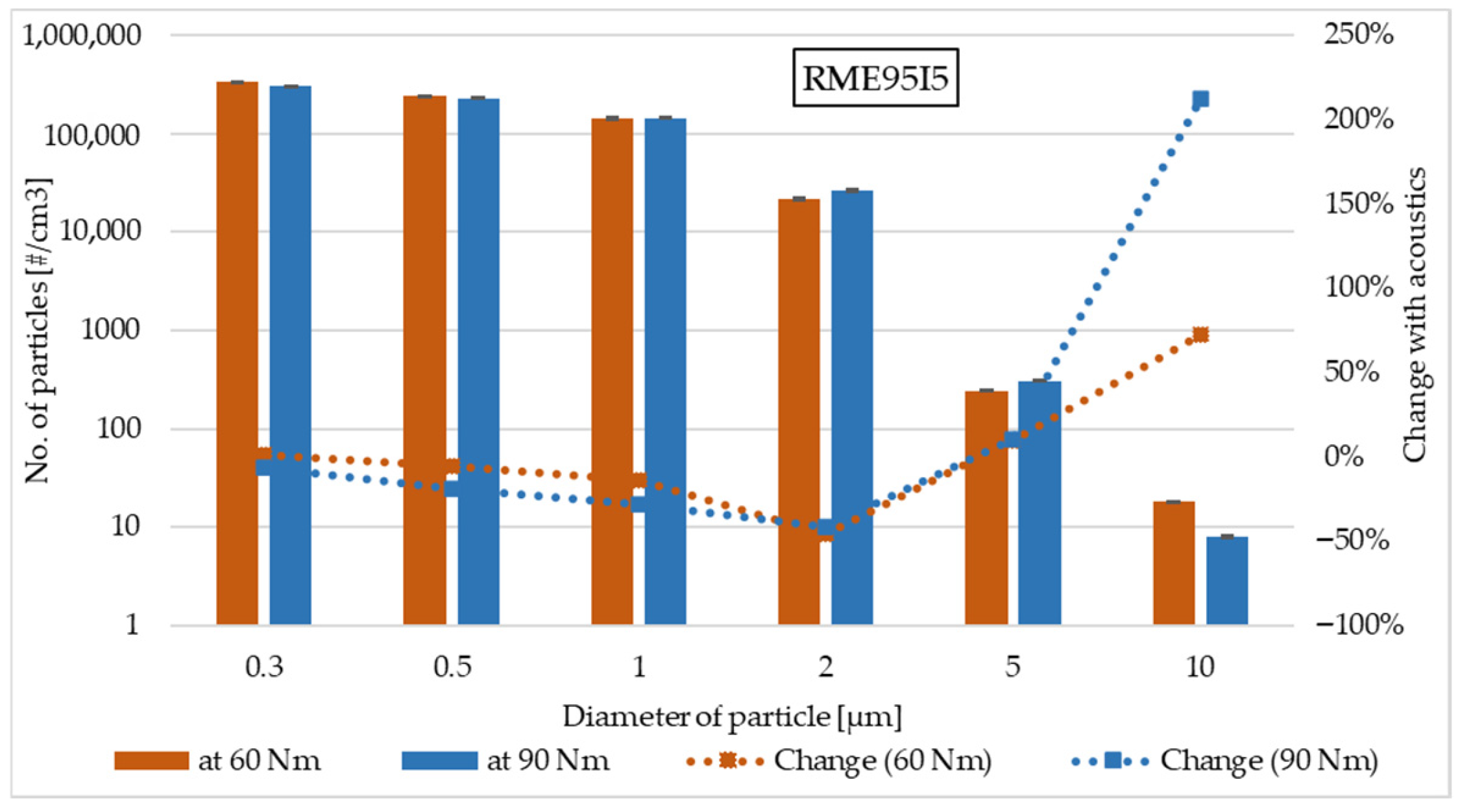

Following the trend, a reduction in particles less than 2 μm is recorded at lower loads. An increase of 22% is observed for 2 μm particles and 27% of 5 μm particles with an increase in load from 60 Nm to 90 Nm. With the presence of acoustic waves, a clear agglomeration pattern of reduced fine particles and increased large particles is found at both loads for RME95I5, as presented in

Figure 5. At lower loads, an average fine particle reduction of 16% is observed along with a 41% increase in average particle sizes above 5 μm. This trend is amplified at higher loads with an average 24% reduction in fine particles and a substantial 111% increase in 5 and 10 μm-sized particles combined. The 11% increase in the oxygen content of the fuel led to a general decrease in emissions for RME95I5 combined with a higher agglomeration rate in comparison with diesel fuel [

44,

45]. The surface characteristics of the emitted particles also plays an important role. Fuels with higher oxygen content produce particles with a stickier nature that increases the efficiency of agglomeration. The addition of isopropanol reduced the C/H ratio of the fuel blend, which is likely to increase the moisture content in the exhaust gases [

21].

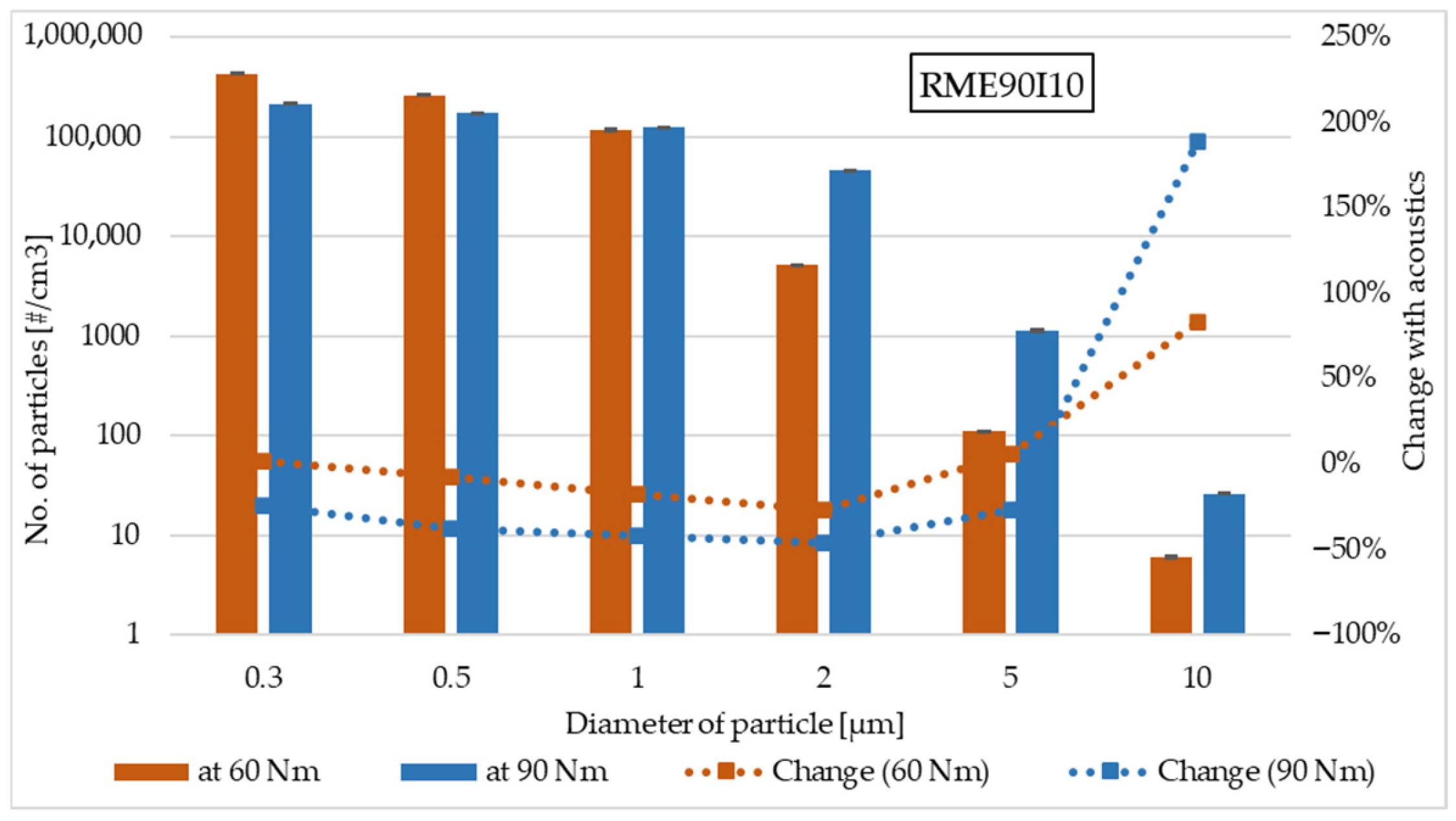

The importance of oxygen in the reduction in particle emission can be highlighted by the reduction in the overall emissions for RME90I10 (presented in

Figure 6).

A 5% increase in isopropanol content (which led to an increase in oxygen content of the prepared fuel blend by 7%) led to a 6% reduction in particle emissions at lower load and a 9% decrease at higher load. The observed emission reduction can also be equally attributable to the reduced carbon content and C/H ratio of the fuel blend. A 1% reduction of carbon content and 2% reduction in C/H ratio is recorded when the isopropanol content is increased from 5% to 10%.

With the presence of acoustic waves, at lower load, a 13% decrease in fine particles is detected with an increase in large particles by 44%. At a similar load, the reduction is lower compared to RME95I5, but the agglomeration efficiency increases by 3%. With an increase in load from 60 Nm to 90 Nm, an average reduction of 35% is observed for particles sized between 0.3 and 5 μm, with an increase in 10 μm-sized particles by 189%. The particles released from using fuels with high oxygen content tend to have better agglomeration results due to the chemical properties that are associated with the fuel. Moisture content also plays an equally important role for achieving better agglomeration, so fuels with comparatively higher hydrogen have higher chances of efficient agglomeration.

4. Discussion

Particle emissions from vehicles play a vital role in increasing air pollution and deteriorating human health. The transportation sector across the world is responsible for a significant amount of particle emissions and this represents a major issue. Reducing particle emissions from diesel engines is one of the most researched areas. The use of alternative fuels and the selection of suitable after-treatment methods are the best solutions to combat growing concerns related to particles.

An acoustic chamber is developed with a sound pressure level of 140 dB and a frequency of 19 kHz, and the three fuels are tested at two different loads of 60 and 90 Nm. Systematic experimental errors are minimized by applying gas flow smoothing and repeated measurements. D100 was found to have a higher number of particulate emissions compared to RME95I5, followed by RME90I10. Several biofuel properties, including a reduced C/H ratio, and increased oxygen content play an important role in controlling emissions. Particles formed during the combustion of biofuel blends contained higher amounts of oxygenated compounds and molecules, making the particle surface more sticky and polar, compared to particles emitted during diesel combustion, which are nonpolar hydrocarbons [

33,

44]. The reduction in C/H ratio also yields better emission results which can be driven from an overall reduction in carbon content of a fuel blend or the increase in hydrogen content, which increases the moisture content when reacted with oxygen and promotes stickiness. The change in carbon and oxygen content of the fuel blends in comparison with D100 is presented in

Table 2. When the isopropanol content increases from 5 to 10%, the oxygen content of RME90I10 increased by 7% compared to RME95I5. This increase in O

2 along with the decrease in carbon content may be the reason for the 5.6% and 8.7% reduction in overall PM emissions at 60 Nm and 90 Nm compared to RME95I5.

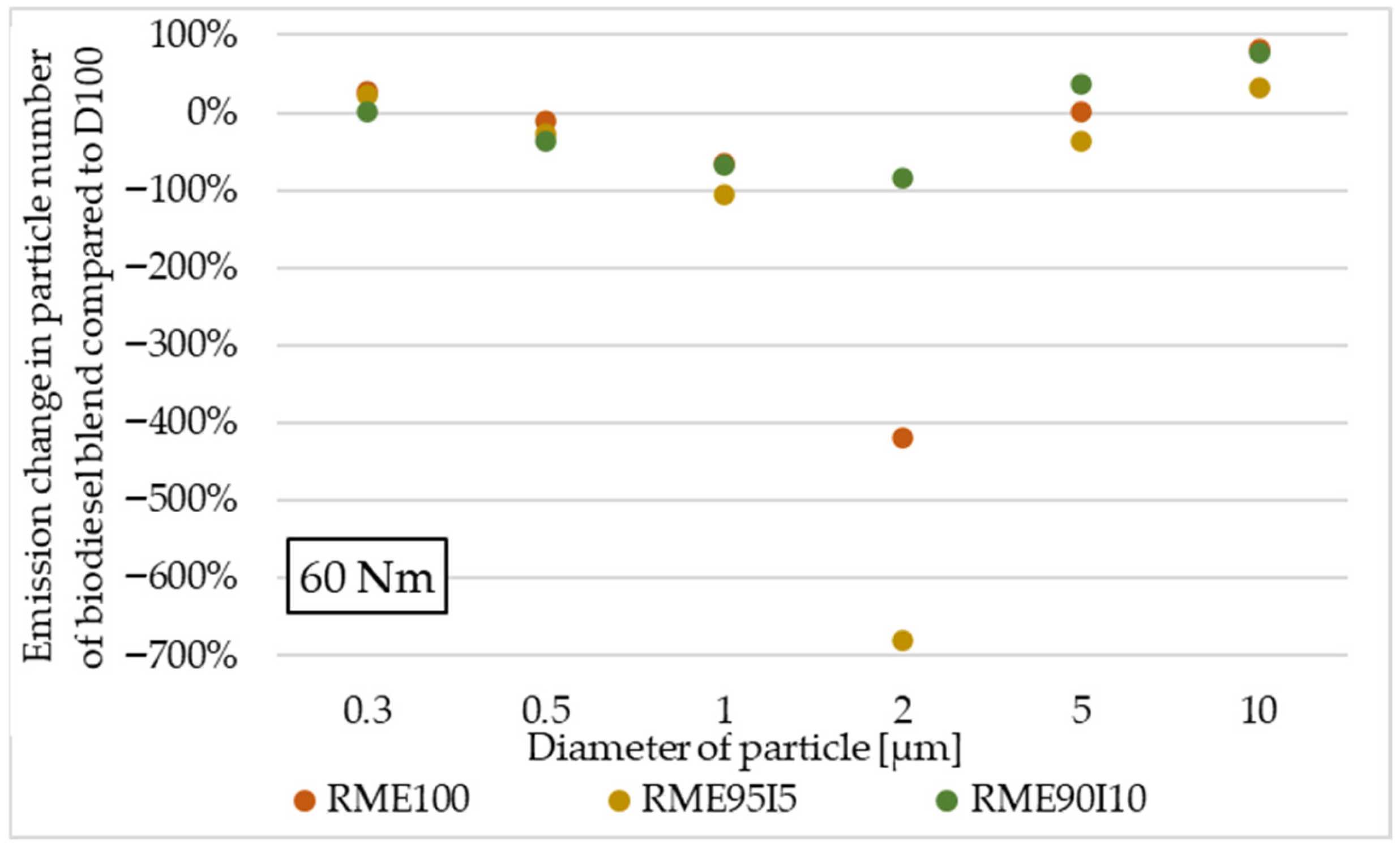

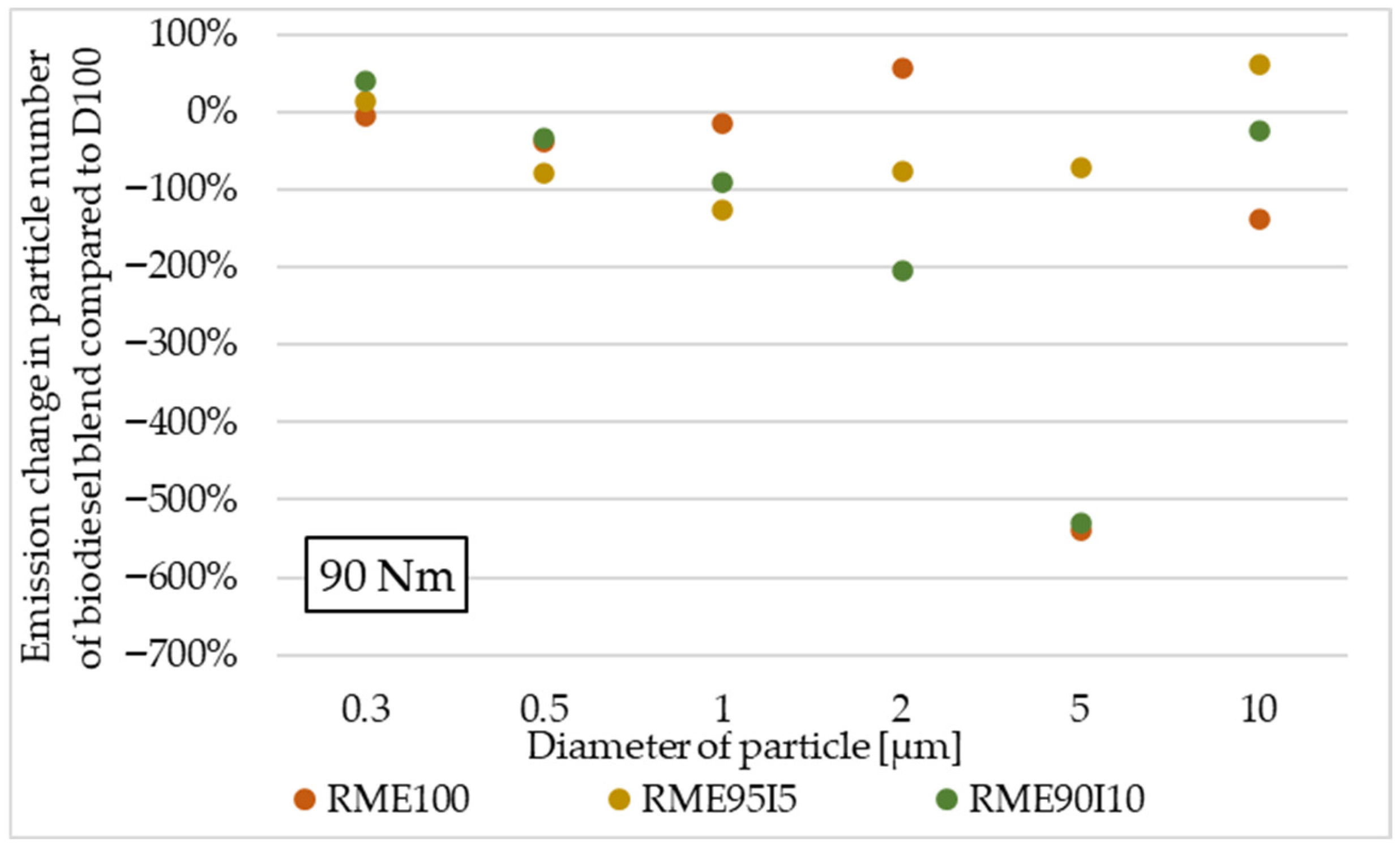

The results presented in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 provide support for the statement that by using/blending alternative fuels with higher oxygen content and lower carbon content, reduction in fine particles can be achieved [

22,

23,

33]. A stable reduction in PM2.5 can be observed for all RME fuel blends in comparison to diesel fuel at both tested loads. Although there is an increase in the particles of the size 5 and 10 μm, these can be filtered more efficiently using the conventional filters when compared to fine particles. The properties of biofuels enable cleaner combustion, and lower particulate-matter emissions during the combustion of biofuels with better chemical properties would help achieve better after-treatment results.

In all the conditions tested, with increasing load, fine particles (PM2.5) are found to decrease and particles of sizes 5 and 10 μm are found to increase, and with the presence of acoustic waves, fine particles are found to agglomerate and form bigger particles. Biodiesel blends show better agglomeration results compared to D100 due to the polar and sticky nature of the oxygenated particles produced during combustion. At 90 Nm, while D100 showed 10% agglomeration, RME95I5 recorded 111% and RME90I10 nearly doubled with 189%. A similar increasing trend is observed even at the lower tested load.

At lower loads, as presented in

Figure 9, with the presence of acoustic excitation, the fine particles are found to consistently decrease with a stable increase in particles of sizes 5 and 10 μm. All tested fuels are found to exhibit this pattern. As the load increases from 60 Nm to 90 Nm, while the overall reduction in particles is found to be higher in comparison to lower loads, the chances of agglomeration of large-sized particles is found to be higher, but only for fuels with higher oxygen content such as RME95I5 and RME90I10, as shown in

Figure 10.

Of all fuel blends for two loads, it is noted that acoustic waves provide the best agglomeration results for fuels with higher oxygen content and lower C/H ratio. Also, with an increase in the load, the reduction in fine particles is found to be consistent and with an added external acoustic excitation, the agglomeration of fine particles is found to occur with increasing the number of large particles.

5. Conclusions

Acoustic agglomeration has proven to be an effective after-treatment solution that helps reduce the amount of ultrafine particulate matter at any load under various fuel blends.

Under external acoustic excitation, particles are excited because of their elevated kinetic energy induced by acoustic waves. This influence causes the particles to excite inside the acoustic chamber, increasing the chances of collision with other particles and thereby agglomerating due to their sticky outer surface. This phenomenon is predominantly observed in fine and ultrafine particles as they have higher kinetic energy due to their lower size and mass.

Engine conditions such as load are found to have a significant influence on the size distribution of the particles. Across all fuel conditions, with increase in load from 60 Nm to 90 Nm, particles of a size bigger than 2 μm are found to increase in a range of 10% with a simultaneous decrease in particle sizes smaller than 2 μm. This is due to the incomplete combustion of fuel at lower loads. The soot formed due to the bad air–fuel mixture at lower loads could also influence the presence of fine particles.

Biodiesel fuel blends show better agglomeration compared to conventional diesel fuel due to its high oxygen content and lower carbon content of the fuel combined with its polar and stickier nature of the particles produced during combustion.

Agglomeration of smaller particles is stable and consistent at lower loads but is inclined towards larger diameters at higher loads.

Better agglomeration is achieved by combining the properties of the biofuel blends. The decrease in the C/H ratio in fuel, driven by the increase in the proportion of hydrogen in the fuel blend results in a higher moisture content in the exhaust gases. More humidified particles and sticky ash/soot fractions promote agglomeration. The decrease in carbon content of the fuel results in fewer fine-particle emissions. The oxygen content of the fuel blend increased by 7% when isopropanol increased from 5 to 10%. This increase in oxygen content led to a decrease in emissions of an average of 7–8% at both loads.

With the available literature on the optimal engine and acoustic parameters and the positive acoustic influence on filtering the fine particles, future research can be carried out by further understanding the impact by changing the frequency and different acoustic and engine parameters.

The area of alternative fuels can also be further explored with a primary focus on reducing the particle emissions, which have a direct impact on human health. The blending of biofuels and the analysis of the impact of composition of fuels and their properties to further reduce the overall emissions are still areas of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.R. and A.R.; methodology, A.R., A.C. and J.M.; software, A.C. and A.R.; validation, S.M.R., A.R., A.C. and J.M.; formal analysis, S.M.R. and J.M.; investigation, S.M.R.; data curation, S.M.R. and A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.R.; writing—review and editing, A.R.; project administration, A.R. and J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AA | Acoustic Agglomeration |

| BMEP | Brake mean effective pressure |

| C/H | carbon/hydrogen ratio |

| D100 | 100% pure Diesel fuel |

| FAME | Fatty Acis Methyl Ester |

| LHV | Lower Heating Value |

| mi | mass fraction of component |

| PM | Particulate Matter |

| PM10 | Particles with diameter ≤ 10 μm |

| PM2.5 | Particles with diameter ≤ 2.5 μm |

| RME100 | 100% pure Rapeseed Methyl Ester |

| RME90I10 | 90% Rapeseed Methyl Ester + 10% Isopropanol |

| RME95I5 | 95% Rapeseed Methyl Ester + 5% Isopropanol |

| vi | volumetric (volume) fraction of component |

| ρi | density of component |

References

- Ashok, B.; Kumar, A.N.; Jacob, A.; Vignesh, R. Chapter 1—Emission Formation in IC Engines. In NOx Emission Control Technologies in Stationary and Automotive Internal Combustion Engines; Ashok, B., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 1–38. ISBN 978-0-12-823955-1. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Ng, E.C.Y.; Surawski, N.C.; Zhou, J.L.; Wang, X.; Gao, J.; Lin, W.; Brown, R.J. Effect of Diesel Particulate Filter Regeneration on Fuel Consumption and Emissions Performance under Real-Driving Conditions. Fuel 2022, 320, 123937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.K.; Refahtalab, P.; Omran, A.; Smith, D.I.; Davies, P.A. An Experimental Study on Performance and Emission Characteristics of an IDI Diesel Engine Operating with Neat Oil-Diesel Blend Emulsion. Renew. Energy 2020, 146, 1041–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, P.; Kahn Ribeiro, S.; Newman, P.; Dhar, S.; Diemuodeke, O.E.; Kajino, T.; Lee, D.S.; Nugroho, S.B.; Ou, X.; Hammer Strømman, A.; et al. Transport (Chapter 10). In IPCC 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Shukla, A.R., Skea, J., Slade, R., Al Khourdajie, A., van Diemen, R., McCollum, D., Pathak, M., Some, S., Vyas, P., Fradera, R., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1049–1160. ISBN 978-1-009-15792-6. [Google Scholar]

- Valeika, G.; Matijošius, J.; Orynycz, O.; Rimkus, A.; Świć, A.; Tucki, K. Smoke Formation during Combustion of Biofuel Blends in the Internal Combustion Compression Ignition Engine. Energies 2023, 16, 3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartík, L.; Huszár, P.; Karlický, J.; Vlček, O.; Eben, K. Modeling the Drivers of Fine PM Pollution over Central Europe: Impacts and Contributions of Emissions from Different Sources. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2024, 24, 4347–4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, F.; Kalghatgi, G.; Stone, R.; Miles, P. The Scope for Improving the Efficiency and Environmental Impact of Internal Combustion Engines. Transp. Eng. 2020, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milojević, S.; Stopka, O.; Kontrec, N.; Orynycz, O.; Hlatká, M.; Radojković, M.; Stojanović, B. Analytical Characterization of Thermal Efficiency and Emissions from a Diesel Engine Using Diesel and Biodiesel and Its Significance for Logistics Management. Processes 2025, 13, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.K.; Ghadikolaei, M.A.; Chen, S.H.; Fadairo, A.A.; Ng, K.W.; Lee, S.M.Y.; Xu, J.C.; Lian, Z.D.; Li, L.; Wong, H.C.; et al. Physical, Chemical, and Cell Toxicity Properties of Mature/Aged Particulate Matter (PM) Trapped in a Diesel Particulate Filter (DPF) along with the Results from Freshly Produced PM of a Diesel Engine. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 434, 128855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Dong, R.; Lan, G.; Yuan, T.; Tan, D. Diesel Particulate Filter Regeneration Mechanism of Modern Automobile Engines and Methods of Reducing PM Emissions: A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 39338–39376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Zhang, Z.; Ye, Y.; Huang, H.; Cao, C. Review of Particle Filters for Internal Combustion Engines. Processes 2022, 10, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworek, A.; Marchewicz, A.; Sobczyk, A.T.; Krupa, A.; Czech, T. Two-Stage Electrostatic Precipitators for the Reduction of PM2.5 Particle Emission. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2018, 67, 206–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Li, Z.; Shen, B.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, D. Simulation of Flow and Soot Particle Distribution in Wall-Flow DPF Based on Lattice Boltzmann Method. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2019, 202, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontses, A.; Dimaratos, A.; Keramidas, C.; Williams, R.; Hamje, H.; Ntziachristos, L.; Samaras, Z. Effects of Fuel Properties on Particulate Emissions of Diesel Cars Equipped with Diesel Particulate Filters. Fuel 2019, 255, 115879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayapureddy, S.M.; Matijošius, J. Reviewing the Concept of Acoustic Agglomeration in Reducing the Particulate Matter Emissions. In TRANSBALTICA XII: Transportation Science and Technology, Proceedings of the 12th International Conference TRANSBALTICA, Vilnius, Lithuania, 16–17 September 2021; Prentkovskis, O., Yatskiv (Jackiva), I., Skačkauskas, P., Junevičius, R., Maruschak, P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 303–311. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, H.S.; Cawood, W. Phenomena in a Sounding Tube. Nature 1931, 127, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Juárez, J.A.; Sarabia, E.R.-F.D.; Hoffmann, T.L.; Gálvez-Moraleda, J.C. Application of the Acoustic Agglomeration to Reduce Fine Particle Emissions in Coal Combustion Plants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1999, 33, 3843–3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilikevičienė, K.; Kačianauskas, R.; Kilikevičius, A.; Maknickas, A.; Matijošius, J.; Rimkus, A.; Vainorius, D. Experimental Investigation of Acoustic Agglomeration of Diesel Engine Exhaust Particles Using New Created Acoustic Chamber. Powder Technol. 2020, 360, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, B.F.; Xiong, J.W.; Wan, M.P. Application of Acoustic Agglomeration to Enhance Air Filtration Efficiency in Air-Conditioning and Mechanical Ventilation (ACMV) Systems. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; He, J.; Wu, L.; Jin, T.; Chen, X.; Li, R.; Ren, P.; Zhang, L.; Mao, H. Health Burden Attributable to Ambient PM2.5 in China. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 223, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Pan, D.; Huang, R.; Hong, G.; Yang, B.; Peng, Z.; Yang, L. Abatement of Fine Particle Emission by Heterogeneous Vapor Condensation During Wet Limestone-Gypsum Flue Gas Desulfurization. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 6103–6109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergen, G. Comprehensive Analysis of the Effects of Alternative Fuels on Diesel Engine Performance Combustion and Exhaust Emissions: Role of Biodiesel, Diethyl Ether, and EGR. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2024, 47, 102307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Goga, G. Emission Characteristics & Performance Analysis of a Diesel Engine Fuelled with Various Alternative Fuels—A Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borucka, A.; Kozlowski, E.; Oleszczuk, P.; Mazurkiewicz, D. The Use of Mathematical Models Describing the Spread of Covid-19 in Strategic State Security Management. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2020, XXIII, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlynski, R.; Kozlowski, E. Selection of Level-Dependent Hearing Protectors for Use in An Indoor Shooting Range. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chlebnikovas, A.; Paliulis, D.; Kilikevičius, A.; Selech, J.; Matijošius, J.; Kilikevičienė, K.; Vainorius, D. Possibilities and Generated Emissions of Using Wood and Lignin Biofuel for Heat Production. Energies 2021, 14, 8471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Bano, K.S.; Mohanty, T.; Kumari, A.; Mehdi, M.M. Exploring Microalgae-Based Biodiesel as an Alternative Fuel: Development, Production Techniques and Environmental Impacts. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 202, 108249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, R.K.; Sarojini, J.; Rajak, U.; Verma, T.N.; Ağbulut, Ü. Alternative Fuel Production from Waste Plastics and Their Usability in Light Duty Diesel Engine: Combustion, Energy, and Environmental Analysis. Energy 2023, 265, 126140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, M.; Bayindirli, C. Enhancement Performance and Exhaust Emissions of Rapeseed Methyl Ester by Using N-Hexadecane and n-Hexane Fuel Additives. Energy 2020, 202, 117643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, J. The Effects of Oxidized Biodiesel Fuel on Fatty Acid Methyl Ester Composition and Particulate Matter Emissions from a Light-Duty Diesel Engine. Master’s Thesis, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Thirumalvalavan, S.; Thanikasalam, A.; Senthilkumar, N.; Sabari, K.; Yuvaperiyasamy, M. Investigation of the Emission and Performance Characteristics of a Direct Injection Diesel Engine Fuelled with Dual Biodiesel Blends. Adv. Eng. Lett. 2025, 4, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhahad, H.A.; Fayad, M.A.; Chaichan, M.T.; Abdulhady Jaber, A.; Megaritis, T. Influence of Fuel Injection Timing Strategies on Performance, Combustion, Emissions and Particulate Matter Characteristics Fueled with Rapeseed Methyl Ester in Modern Diesel Engine. Fuel 2021, 306, 121589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szyszlak-Bargłowicz, J.; Wasilewski, J.; Zając, G.; Kuranc, A.; Koniuszy, A.; Hawrot-Paw, M. Evaluation of Particulate Matter (PM) Emissions from Combustion of Selected Types of Rapeseed Biofuels. Energies 2023, 16, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 14214:2012+A2:2019; Liquid Petroleum Products—Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAME) for Use in Diesel Engines and Heating Applications—Requirements and Test Methods. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Orynycz, O.; Zimakowska-Laskowska, M.; Kulesza, E. CO2 Emission and Energy Consumption Estimates in the COPERT Model—Conclusions from Chassis Dynamometer Tests and SANN Artificial Neural Network Models and Their Meaning for Transport Management. Energies 2025, 18, 3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okcu, M.; Varol, Y.; Altun, Ş.; Fırat, M. Effects of Isopropanol-Butanol-Ethanol (IBE) on Combustion Characteristics of a RCCI Engine Fueled by Biodiesel Fuel. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 47, 101443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayapureddy, S.; Matijošius, J.; Rimkus, A. Comparison of Research Data of Diesel–Biodiesel–Isopropanol and Diesel–Rapeseed Oil–Isopropanol Fuel Blends Mixed at Different Proportions on a CI Engine. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayapureddy, S.; Matijošius, J.; Rimkus, A.; Caban, J.; Słowik, T. Comparative Study of Combustion, Performance and Emission Characteristics of Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil–Biobutanol Fuel Blends and Diesel Fuel on a CI Engine. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimkus, A.; Matijošius, J.; Manoj Rayapureddy, S. Research of Energy and Ecological Indicators of a Compression Ignition Engine Fuelled with Diesel, Biodiesel (RME-Based) and Isopropanol Fuel Blends. Energies 2020, 13, 2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 590:2013+A1:2017; Automotive Fuels—Diesel—Requirements and Test Methods. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- JIS B 9921:1997; Vibration—Mechanical Vibration—Calibration of Vibration and Shock Pick-Ups. Japanese Standards Association: Tokyo, Japan, 1997.

- ISO 21501-4:2018; Determination of Particle Size Distribution—Single Particle Light Interaction Methods—Part 4: Light Scattering Airborne Particle Counter for Clean Spaces. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Kilikevičienė, K.; Chlebnikovas, A.; Matijošius, J.; Kilikevičius, A. Investigation of the Acoustic Agglomeration on Ultrafine Particles Chamber Built into the Exhaust System of an Internal Combustion Engine from Renewable Fuel Mixture and Diesel. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghadikolaei, M.A.; Cheung, C.S.; Yung, K.-F. Study of Combustion, Performance and Emissions of Diesel Engine Fueled with Diesel/Biodiesel/Alcohol Blends Having the Same Oxygen Concentration. Energy 2018, 157, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Wang, X.; Hamilton, J.; Negnevitsky, M. Numerical Investigation on Hydrogen-Diesel Dual-Fuel Engine Improvements by Oxygen Enrichment. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 25418–25432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).