1. Introduction

The growing penetration of Renewable Energy Sources (RESs) in distribution grids is a cornerstone of the sustainable energy transition, yet it also introduces technical challenges and operational constraints that limit the full exploitation of RES production [

1,

2]. To address these issues, novel flexibility services and management strategies are increasingly being explored as effective strategies to manage dispatchable technologies, reduce curtailment, and enhance hosting capacity. In recent years, this topic has gained significant attention from both researchers and power engineering companies [

3,

4]. Among the proposed approaches, different control architectures have been considered to coordinate flexibility resources and support the reliable integration of RES into distribution grids.

A centralized control strategy, where the Distribution System Operator (DSO) manages numerous dispatchable units across MV and LV networks, could maximise RES integration [

5]. Yet, this approach is limited by the absence of TSO/DSO coordination and suitable architectures to handle large sets of user-owned flexibility resources [

6]. Consequently, DSOs are also looking into decentralized solutions for grid support services, which appear more feasible under current conditions [

7].

In this context, Renewable Energy Communities (RECs) represent a possible realization of such paradigms, fostering decentralized, participatory, and sustainable approaches to energy production and consumption. By aggregating distributed resources, they pursue self-sufficiency and efficiency while operating independently of the DSO. As highlighted in [

8], the effective integration of coordination strategies within RECs is essential to enhance DSO flexibility and to optimize the community’s impact on the distribution network. Their contribution to power system support has been demonstrated in [

9], where the optimal management of local storage improved self-consumption and provided ancillary services. Beyond shared and self-consumed energy, many RECs integrate flexibility assets such as storage or controllable loads, positioning them as suitable providers of grid services [

10]. The literature further highlights their potential: distributed storage for regulation, demand response strategies [

11,

12], power-sharing models for maximising local generation [

13], and EV integration frameworks that enhance PV utilisation and limit peak demand [

14].

REC can also contribute to grid “flexibilization” by operating in Virtual Islanding (VI), a management strategy that allows a portion of the distribution grid to temporarily operate as an islanded system by means of a null active power balance while remaining connected to the main grid, in contrast to physical islanding [

15]. It enables higher RES hosting capacities by mitigating local congestion and voltage issues without requiring full disconnection [

16]. The VI service, as designed, also generates economic benefits for community members by increasing the amount of locally shared energy that is financially compensated in accordance with EU regulations, as preliminarily analyzed in [

17]. Moreover, the provision of this service by RECs requires appropriate remuneration mechanisms, which is considered in addition to the economic benefits associated with the maximization of shared energy. A dedicated market, based on auctions and negotiation procedures, has to reward RECs proportionally to the flexibility and support they provide to the network, as highlighted in [

18]. By leveraging the role of RECs, VI can ease the integration of a considerable amount of RES into the distribution power grids [

19]. Moreover the influence of the number of RECs on the effectiveness of VI in a portion of a distribution network was explored [

20]. In juxtaposition with VI, Virtual Power Plants (VPPs) aggregate diverse DERs—such as renewables, storage, and controllable loads—into a unified portfolio that can be remotely controlled to balance supply and demand, provide ancillary services, and participate in electricity markets [

21]. Their greatest strength lies in coordinating heterogeneous, geographically dispersed assets as if they were a single power plant, maximizing both economic value and grid stability. A REC can be operated as a community-based Virtual Power Plant (cVPP), where DERs are coordinated via an ICT-based control system and collectively managed by active participants [

22].

Taking a closer examination of the resources that can participate in a REC and how they can be aggregated, ref. [

23] examines aggregated flexible energy resources for ancillary services, covering the management of prosumers and communities. These resources—shiftable, controllable, or curtailable loads; generation; and storage—enable higher integration of intermittent renewables, support frequency and voltage regulation, and highlight the EMS structures and market issues needed to fully exploit local electricity. The study in [

24] investigates how the economic and environmental performance of a REC is influenced by factors such as technology characteristics (e.g., renewable generation, flexible loads, storage), participant types (consumers and prosumers), and electricity sharing or trading agreements. The study demonstrates that sufficient PV capacity and adoption rates, combined with competitive aggregation tariffs, can generate positive outcomes for both consumers and prosumers. An energy community model is proposed to test various market types, considering participants from different economic sectors and scenarios defined by willingness to participate, technology features, PV sizing, and local electricity market (LEM) models. Five REC typologies are examined, covering combinations of PV, EVs, and BESS and diverse load profiles including residential, industrial, hotels, and universities.

Reference [

25] analyzes the technologies integrated into REC projects (PV, wind, biogas, hydro, and storage) and socioeconomic frameworks, management models, and local engagement strategies that support their success, alongside the distribution of RECs in Europe and globally. Several studies have focused on exploring the impact of different technologies on REC performance: Ref. [

26] addresses the influence of PV size, ref. [

27] examines the effect of member number, ref. [

28] addresses the optimal PV and BESS sizing, ref. [

29] addresses the combination of PV with other RES, ref. [

30] investigates the combined effect of WT and PV, ref. [

31] examines the sizing of BESS to evaluate REC potential, and finally, ref. [

32] demonstrates the essential role of BESS in achieving self-sufficiency. Overall, the impact of REC composition on the provision of flexibility services to the distribution network during VI operation has not yet been explored. Another aspect to be further developed, which is not addressed in this article as it falls outside the scope of the proposed analysis, concerns the design of a control architecture aimed at optimizing the use of flexible resources during the DSO-requested VI period based on forecasts and real-time measurements, while also enabling the rapid compensation of load and RES fluctuations, as highlighted in [

33].

This study aims to evaluate the impact of REC composition on the ability to address grid operational challenges when VI is requested by the DSO and to identify configurations that are particularly effective in this context. To achieve this, a Monte Carlo simulation is conducted: after fixing the number of RECs in the testbed distribution network, the technologies present in the grid are randomly assigned to the existing RECs, enabling the assessment of multiple configuration scenarios. Building on these scenarios, OPF calculations are performed to assess how VI operation, even under different REC compositions, affects the secure operation of the distribution network.

A literature comparison of mathematical formulations, network models, and other features presented in previous works related to VI service is given in

Table 1. The proposed approach constitutes a significant and highly relevant improvement over the authors’ previous developments, since the results derived from this new randomized approach have allowed a comprehensive generalization of the effectiveness of the proposed VI control strategy. The stochastic nature of the Monte Carlo simulation successfully overcomes the potential for bias inherent in previous studies that stemmed from the specific, fixed choice and location of DERs. This robust validation demonstrates the broader applicability of the proposed approach. Moreover, this extensive testing framework seamlessly incorporates essential features retained from prior studies, specifically the testing on a real distribution network model and the exploration of sensitivity signals. Thus, this work not only introduces a novel, generalized methodology but also validates established capabilities within a more rigorous and extensive testing environment.

2. Mathematical Formulation

The following section describes the methodology used to assess VI effectiveness considering the presence of multiple RECs located in the grid. The hypothesis underlying this study assumes the presence of multiple flexible resources such as RESs, comprising photovoltaic and wind turbine power plants, BESSs, and controllable and/or interruptible loads.

Two different formulations are described. The first one is based on an ideal centralized approach (DSO Control), where all flexible resources in the grid are directly controlled by the DSO in order to mitigate critical operating conditions. The second formulation is based instead on the proposed decentralized approach (VI-Control). The flexible resources are assumed to be distributed among multiple RECs. Each REC actuates a decentralized VI control over its own resources.

2.1. DSO Control

The first approach has been formulated on the assumption that the DSO has complete control of resources within the grid, ensuring the best solution in terms of network violations, using flexible resources efficiently. Although this type of approach is hardly implementable in the real world, because of the the lack of observability in the distribution network and the need to have access to monitoring and control of numerous resources belonging to private and industrial users, this formulation is as an ideal benchmark used for the purpose of comparison to assess how closely the proposed VI decentralized approach can approximate this ideal scenario.

The formulation of the DSO-Control problem, based on the Distribution Optimal Power Flow (DOPF) presented in [

34], aims to minimize the overall use of control resources in order to mitigate grid violations. The objective function, considering the total number of RECs

, is, therefore, the following:

where

,

, and

are, respectively, the number of RESs, BESSs, and DRs in the

REC;

is the initial active power injection from the generic

RES in the

REC;

is the initial active power injection from the

BESS in the

REC;

is the initial active power absorbed by the generic

controllable load DR in the

REC. The control variables

,

, and

are defined analogously to their respective initial values. The maximum and minimum values of the control variables are used to normalize the control effort spent on each resource with respect to its capability. Depending on the type of control resources used, the control range may vary. For this study, it was assumed that RES operates at MPPT in each time step, so the initial generation value

coincides with the upper limit

. For interruptible loads, they can only be controlled by downward regulation, so the initial value

coincides with the maximum value

. For controllable loads, it was assumed that they can be controlled by upward and downward regulation. Finally, for storage systems,

and

represent the maximum charge and discharge values, respectively.

The minimization of (

1) is subject to equality constraints, represented by the load flow nodal balance Equations (

2) and (

3), and inequality constraints (

4)–(

6), including security constraints on bus voltages, line loading, and transformer power limits:

where

and

are the total active power generated and absorbed at the

bus;

and

are the total reactive power generated and absorbed at the

bus. Regarding inequality constraints, the voltage limits are set between

of the nominal per unit values, while the line and transformer limits are based on the rated per unit ampacity and power capacity, respectively.

In order to explore feasible and unfeasible solutions, inequality constraints (

4)–(

6) have been reformulated into quadratic penalty functions (

7)–(

9) and added to (

1), resulting in an augmented objective function:

where

is defined as follows:

The penalty factors

,

, and

differ from zero only when the related electrical variable exceeds the limits considered. The augmented objective function is then

depending on the set of state variables

and control variables

In order to include limits in the control resource range, the following hard constraints must be considered within the formulation:

The proposed DSO-Control formulation aims to minimize (

10). Subject to (

2), (

3) and (

11)–(

13), this formulation is generally enough for solutions with any DOPF routine.

2.2. VI-Control

The VI-Control approach is based on the decentralized use of flexibility resources, resulting in multiple decoupled optimization problems. Each problem aims to optimally manage the flexible resources belonging to a single REC in order to satisfy the respective Virtual Islanding constraint. The formulation does not include network constraints, since the control of resources is performed by REC users who do have no knowledge of the grid model nor of its operating condition.

This type of approach allows the problem to be solved easier, with a lower computational effort; however, the solution provided can only be suboptimal if compared to DSO-Control. The decentralized approach aims to minimize, for each

REC, the control effort of flexible resources with respect to the BRS, in order to achieve the Virtual Islanding condition. The objective function is therefore as follows:

The relation (

14) previously described is subject to the Virtual Islanding constraint, which must be satisfied by each

REC:

where

and

are, respectively, the total non-dispatchable generation and load in the

REC. Please note that in (

15), a load convention for storage units was assumed (i.e.,

is positive during charge). Still, constraints (

11)–(

13) have to be considered to not exceed the limits of control resources. The proposed VI-Control formulation aims simply to minimize, for each

i-th REC, (

14), subject to (

11)–(

13) and (

15).

The problem proposed in this way is more easily solved and less computationally cumbersome, not considering grid constraints and load flow equations. Being based solely on the achievement of the VI condition, the problem can therefore be decoupled and solved independently for each REC.

To assess the effectiveness of the Virtual Islanding condition, the operating point reached through VI-Control can be analyzed with an ex post load flow. Security violations that have not been solved by the VI-Control will be collected in order to compare this solution with the ideal DSO-Control solution.

3. Methodology

In this section, the methodology adopted for this study is described. First of all, an initial analysis is conducted to assess the operating conditions of a distribution network, over an extensive time window (i.e., one entire month of operation), assuming known load demand and RES production profiles. This initial scenario is characterized by a very high penetration of RES, and it is referenced as the Base Reference Scenario (BRS) in the following subsections. BRS analyses are performed on an hourly basis, permitting the observation of the operation of the network without implementing any control strategy, and potential violations of technical grid limits are collected across the entire time window.

Once potential grid constraint violations are detected, centralized DSO-Control is assumed to be applied onto the entire observation window. By solving the Distribution Optimal Power Flow (DOPF) problem previously presented for each hour, it is possible to assess how the centralized control of assumed flexibility resources could ideally solve potential security violations.

This ideal solution can then be compared to the solutions obtained, applying VI-Control across the observation window. The study in [

20] has already shown how VI-Control can solve most of the security violations, or at least alleviate them, without the need of a centralized approach. However, the solutions found were referred to a specific test case, assuming a single distribution of flexible resources among RECs, which potentially introduced a bias into the results.

This study aims to overcome this limitation, applying the VI-Control to a large number of scenarios, where the allocation of flexible resources within the RECs is entirely randomized. Since flexible resources are randomly distributed across the system, the overall solutions obtained through VI-Control will not be skewed by favorable aggregations of resources around specific feeders or geographical areas.

3.1. Monte Carlo Sample Generation

In this study, the scenarios used to test VI-Control are created using a Monte Carlo algorithm. The Monte Carlo algorithm is used to generate a set of

, and each sample involves a random association of resources with one of the

RECs. An example of the generated samples and of the association of each resource to a REC is given in

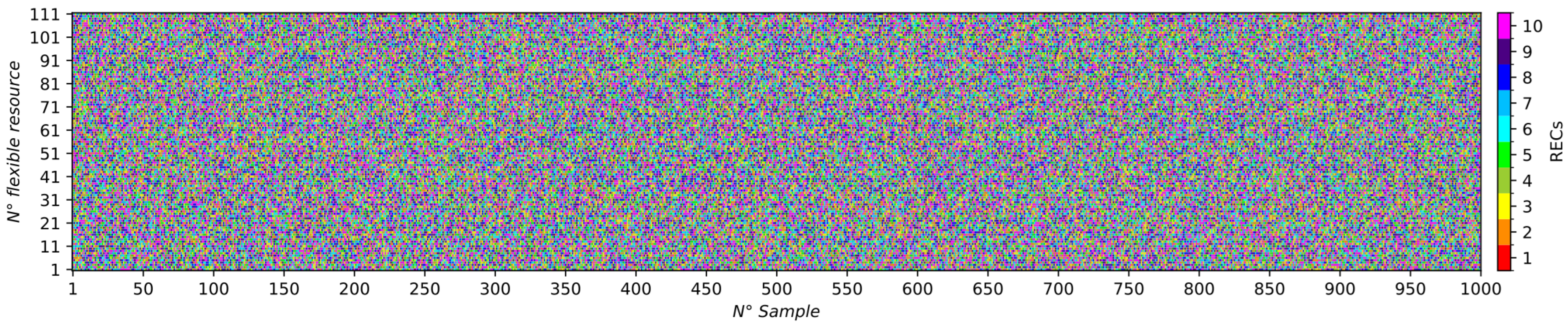

Figure 1. The figure shows the 1000 samples generated and the association of 111 flexible resources with the 10 RECs hypothesized. For each column, representing the generic sample, the association of each flexible resource with one of the 10 RECs considered is denoted by different colored dots.

It should be noted that each generated sample only refers to a different allocation of the flexible resources among the RECs. Flexible resources always stay connected to the same bus so that the initial conditions are not changed and a comparison to all other solutions (BRS, DSO-Control, and other VI scenarios) is possible.

During sample generation, no constraints associated with the number of resources or the overall regulation capacity of the resources in the individual RECs were considered. These arrangements could actually be used to filter out samples that lead to inconsistent results or outliers due, for example, to an unbalanced number of resources in RECs or the insufficient regulation capacity to pursue the Virtual Islanding condition. Nevertheless, not considering these restrictions provides an idea of the VI-Control behavior even in non-optimal conditions.

3.2. Solving Algorithm

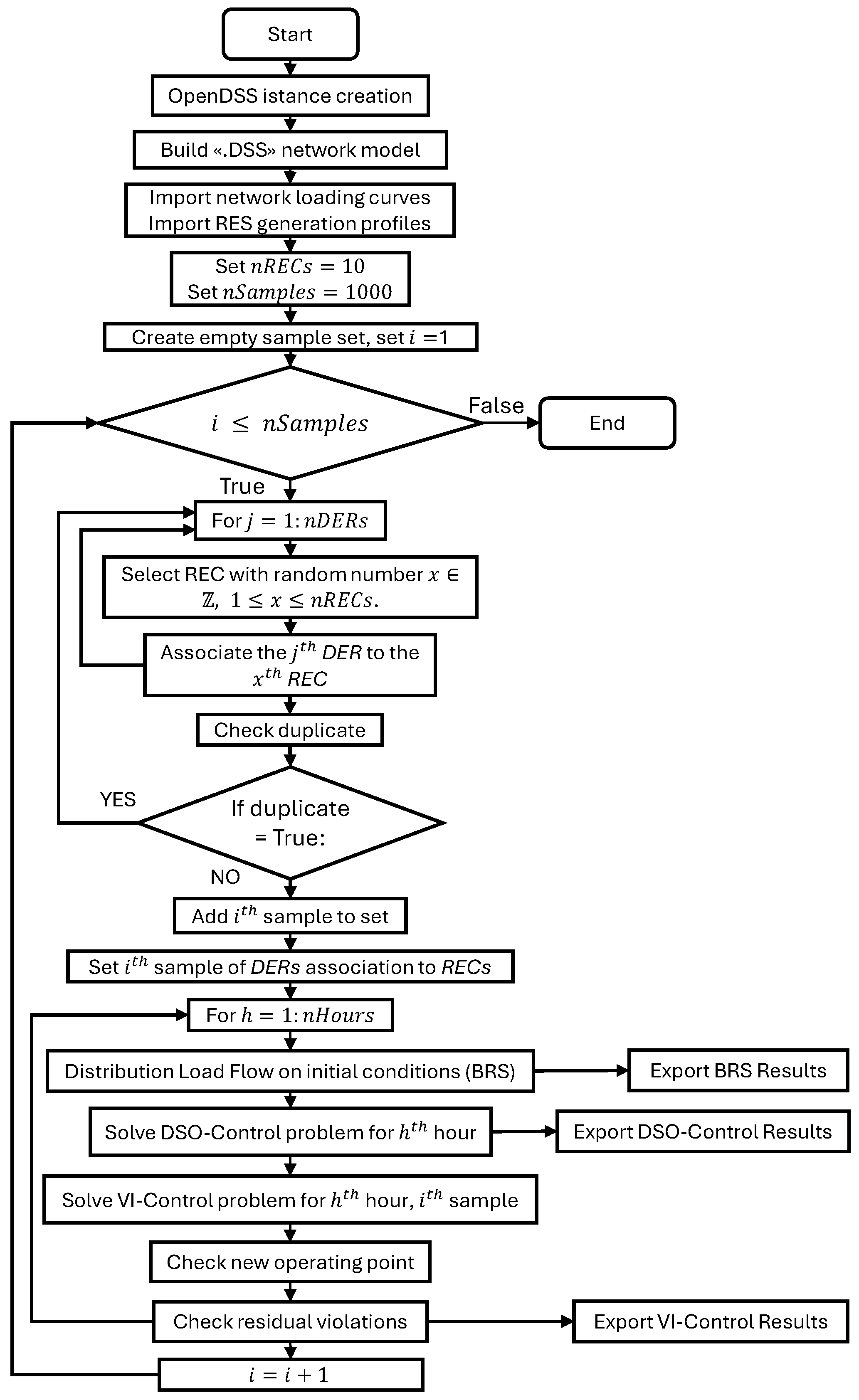

The implemented solution algorithm is shown in

Figure 2.

The algorithm starts by setting the communication between the Python environment and OpenDSS; this is carried out by importing the module win32com.client onto the Python script. The module allows access to the OpenDSS COM module. The COM interface allows the OpenDSS functions to be executed from an external environment. In addition, text-based commands can be used to read/write the properties of the component models implemented in the OpenDSS engine. The OpenDSS software (v. 9.6.1.1) is used to evaluate the initial limit violations in the BRS, and it is called multiple times during the DSO-Control routine to execute AC-LF analyses with the updated value of the control variables calculated on each DOPF iteration. Having set the COM interface, the algorithm builds the DN model and imports historical data of load demands and RES generation profiles.

Afterwards, the number of RECs and Monte Carlo samples to be generated is set. Thus, the Monte Carlo algorithm is performed, associating, for the sample, each DER with the REC. A set of generated samples is created to control possible duplicates and avoid samples with the same association of DERs with RECs. Once the sample is added to the set and the association of DERs with RECs is carried out, the solving algorithm is executed. For each hour of the simulation period, an initial load flow analysis is performed to collect violations for the BRS. Thereafter, the VI-Control optimization problem is executed, collecting the residual violations not mitigated. Please note that, in the case of DSO-Control, the resolution algorithm does not comprise the Monte Carlo algorithm, as it is based on the use of all flexible resources, not considering the REC association.

The algorithm was implemented in Python, using the open source software OpenDSS for DN modeling and load flow analysis. Within the solving routine, the software is used multiple times to evaluate the new operating point based on the updated control variables calculated in the Python environment. To reduce the computational effort, the execution method adopted for both VI-Control and DSO-control relies on the quasi-Newton method. In the DOPF routines, gradients are calculated numerically, as largely discussed in [

34], whereas in VI-Control, the gradients are calculated analytically. The main advantages related to the use of the quasi-Newton approach rely on its simplicity and the possibility of avoiding the calculation of the Hessian matrix inverse, which is instead substituted by an approximated formula. In particular, among the different formulations presented in the literature, the BGFS update formula is used, as shown in (

16):

where

is the approximation of the inverse of the Hessian matrix to be computed, and

is the distance between the vector of control variable

u, while

is the difference between the gradient of the objective function

, both evaluated in two consecutive iterations

k and

. The update method is shown in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: BFGS |

- 1

Set and convergence tolerance : - 2

Compute Inverse Hessian approximation - 3

- 4

While : - 5

Compute search direction ; - 6

Compute with found by Line Search; - 7

Compute e ; - 8

Compute with ( 16); - 9

- 10

end (While)

|

The relation allows us to evaluate the inverse approximation of the Hessian matrix, and it has been adopted due to its efficiency and self-correction capacity with respect to bad approximations carried out during the algorithm routine. In addition, compared to other approximation formulas, more computational effort can be saved using the relation (

16) to evaluate the direction of the search for the update of control variables.

Furthermore, the VI-Control previously formulated may include sensitivity signals, obtained centrally by DSO-Control. These signals are based on the operating point reached with the centralized solution and could be adopted to limit or inhibit the use of some flexible resources. The sensitivities could actually improve the correct control of these flexible resources, helping to avoid reaching a worst operating condition on the grid. For example, in a feeder experiencing overvoltage violations, the BESS could be limited to a charge increase, in the same way a controllable load can be set only to the upward regulation. This is a very simple feature that can be implemented by changing the maximum and minimum range values explicated in (

11)–(

13).

4. Results

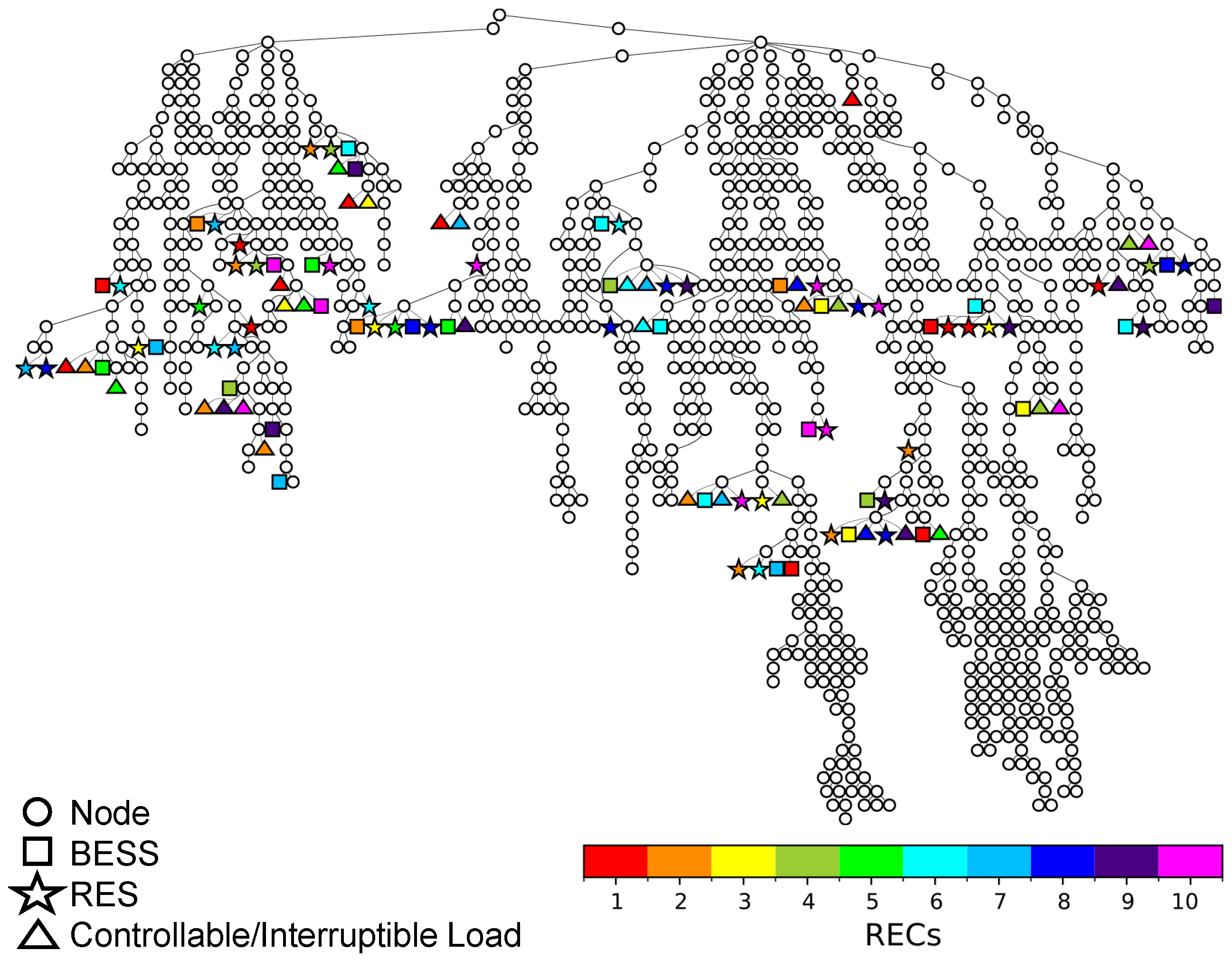

The test results were carried out considering the model of a real primary DN, which supplies electricity to a medium-sized Italian city (about 50,000 inhabitants). The network is served by 2 HV/MV transformers (150/20 kV and rated capacity of 30 and 25 MVA), 11 MV feeders, 903 nodes, 930 lines and 502 loads. In addition, the presence of 111 distributed resources (i.e., 34 interruptible/controllable loads, 33 batteries, 34 photovoltaics, 10 wind power plants) belonging to the RECs has been taken into account.

Figure 3 shows the topology of the DN, with one of the random samples generated, the flexible resources added to the DN are indicated with different shapes (square, star, and triangle) based on the relative technology, while the association with 10 RECs is shown illustratively using different colors.

4.1. Case A: VI-Control of 10 RECs

In this first test case, simulations were run considering

and

. The samples were generated by the Monte Carlo algorithm and, for instance, are the same ones previously shown in

Figure 1. As input for the case study, load demand data, measured at each feeder on hourly basis, were exploited. Moreover, photovoltaic and wind turbine generation curves were used to define RES production curves. To develop a realistic scenario in the context of energy transition, the guidelines of the Italian Energy Plan (PNIEC) were followed, increasing the load demand by a 20%, while the overall generation of RES was adjusted to cover at least 65% of the electrical load. Despite the readiness of the six-month measures, to reduce the computational time, simulations were carried out considering the month (i.e., May,

), characterized by the highest number of critical operating conditions. With these assumptions, the energy demanded during the simulated month in the BRS is about

GWh, while the total generated RES energy is

GWh. The monitored peak load is

MW, and the maximum RES generation is

MW. Regarding the variation of control resources, based on the limitations described in (

11)–(

13), the generation of RES varied from a maximum of

to 0 MW according to downward regulation, while the demand of interruptible loads ranged from 0 to

MW. Controllable loads could vary from 0 to 20 MW, following the upward/downward regulation, while storage systems varied between a maximum charge and discharge of 1 MW.

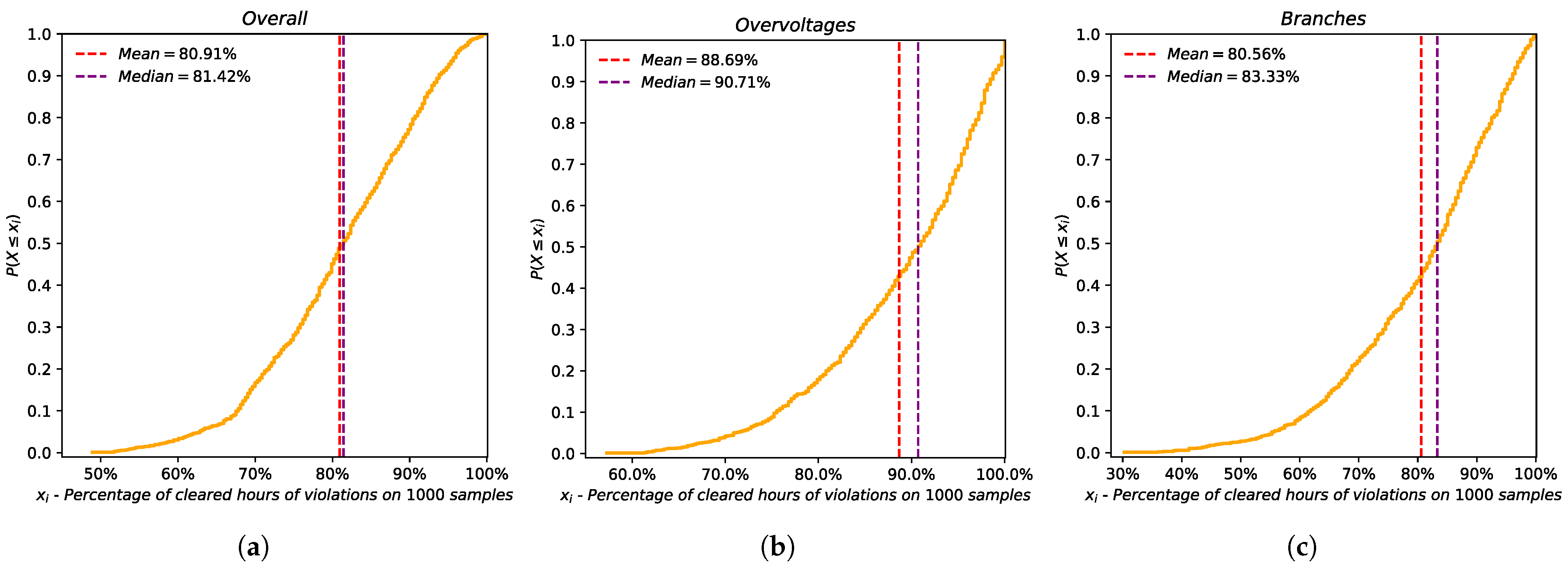

For each sample to which DSO-Control and VI-Control were applied throughout the entire simulation period, the number of residual violations was collected. In addition, the number of hours during which at least one violation persists was also analyzed. In order to describe the results obtained with 1000 samples, the mean and median indicators and cumulative distribution functions were also considered.

A summary of the results derived from the simulations performed is shown in

Table 2, indicating the number of hours in which at least one violation of the grid constraints is experienced.

As can be seen, the BRS is characterized by many hours of violation; this is due to the fact that the scenario developed comprises high RES penetration in the grid in order to reach de-carbonization goals. This condition clearly highlights the necessity of adopting control strategies and organizing resources to support grid operation. As mentioned above, the adoption of the DSO-Control leads to the best solution, clearing all violations in the grid, with the minimum control effort of resources; however, this approach can be considered as an ideal application of control to the assumed flexibility. Regarding the results obtained with VI-Control, the mean and median values related to the set of solutions obtained by 1000 samples are also shown (i.e., on average, a sample leads to only 37 h of unsolved overvoltage violations). It can be seen that the violations were resolved in more than 80% of the hours. The presence of outliers can be observed by looking at the lower values of the median. No violations of transformer power limits remained.

The number of violations detected and not mitigated during simulations is reported in

Table 3.

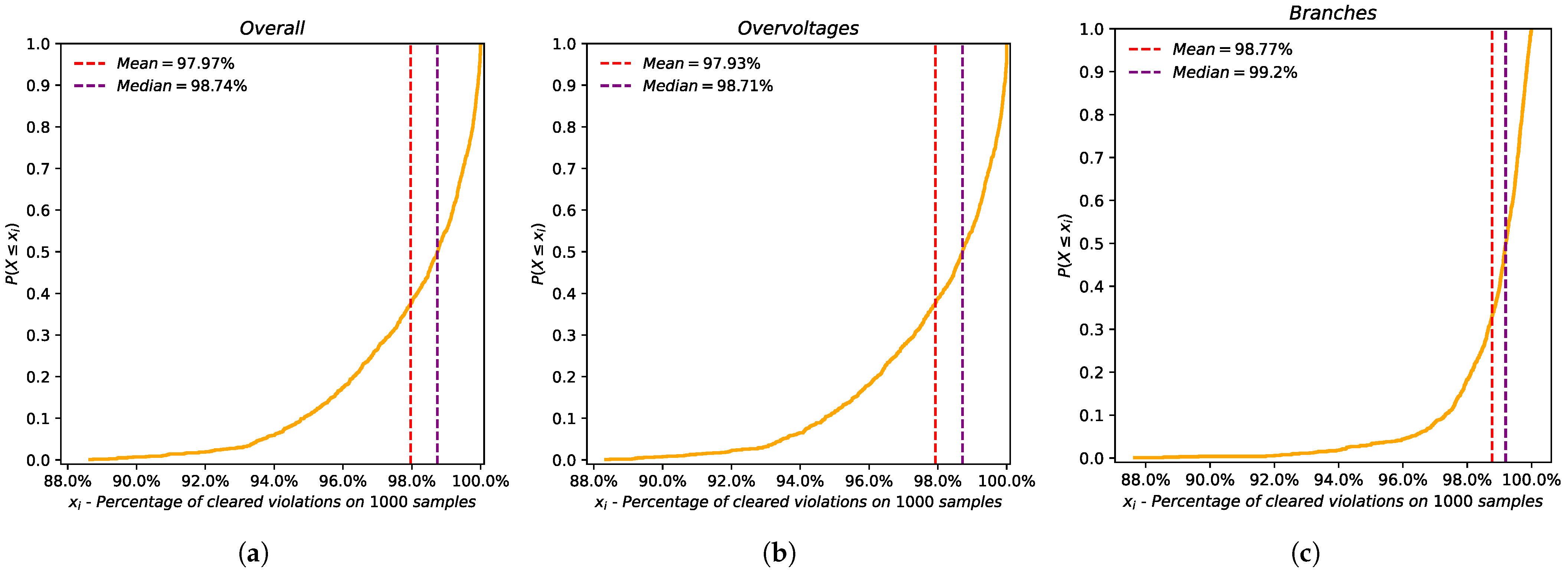

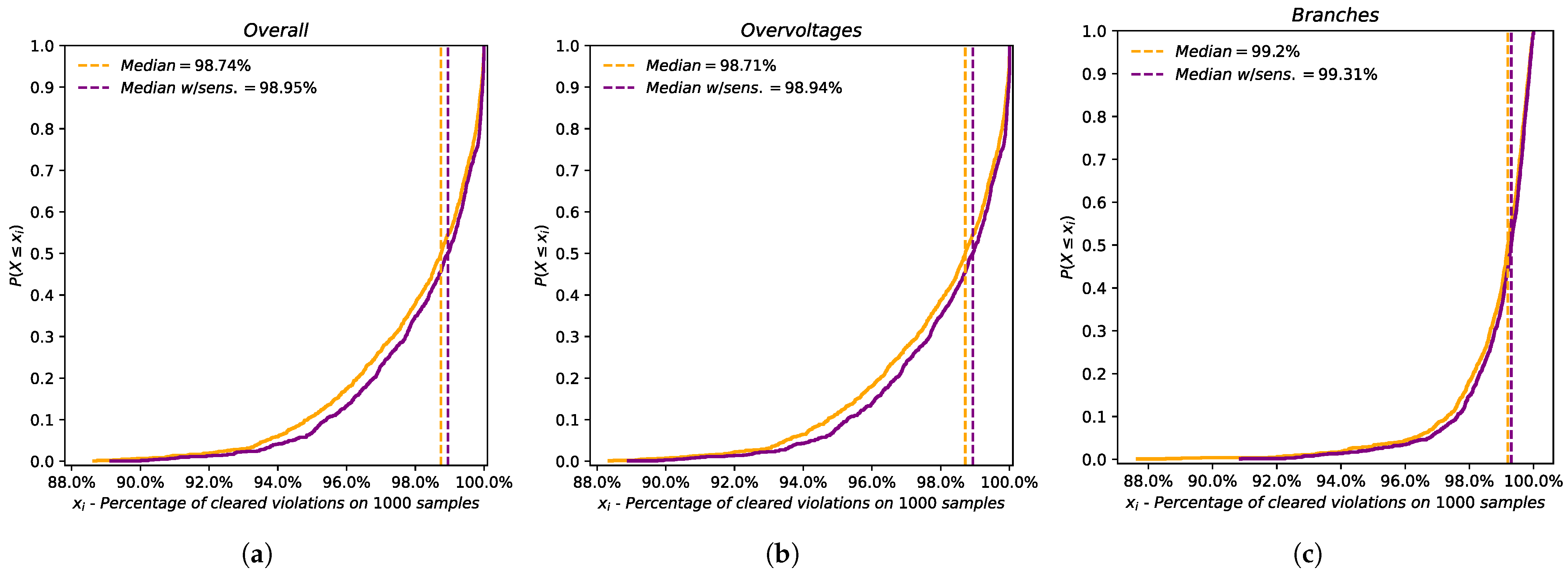

It is more easy to notice the positive impact of VI-Control in the grid by looking at the mean and median values of each type of unsolved violation. The average percentage reduction is over 98% for lines and over 97% for voltage violations. No violations remained unsolved for the transformers. Once again, the discrepancy between the mean and median values reflects the presence of some outliers. More explanations can be given by looking at the cumulative distribution functions represented in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

As can be seen, the mean and median values are greater than 80% for each type of violation registered in the BRS. Even in the worst-case scenario, the percentage of hours with overall mitigated violations is roughly 50%; however, in hours where violations are not totally mitigated, the number and entity of the violations are sensibly low.

Other results can be seen in the percentage of the number of mitigated violations, where the mean and median values are more than 98%, with different samples reaching 100% of mitigated voltage and branch violations. The worst-case scenario results in a percentage mitigation of approximately 88%, proving that samples in which more hours with critical operating conditions persist are actually characterized by a low number of unsolved violations. As shown in the cumulative distribution curve in

Figure 5, VI-Control permitted the solution of about 94% of overall violations with 95% confidence.

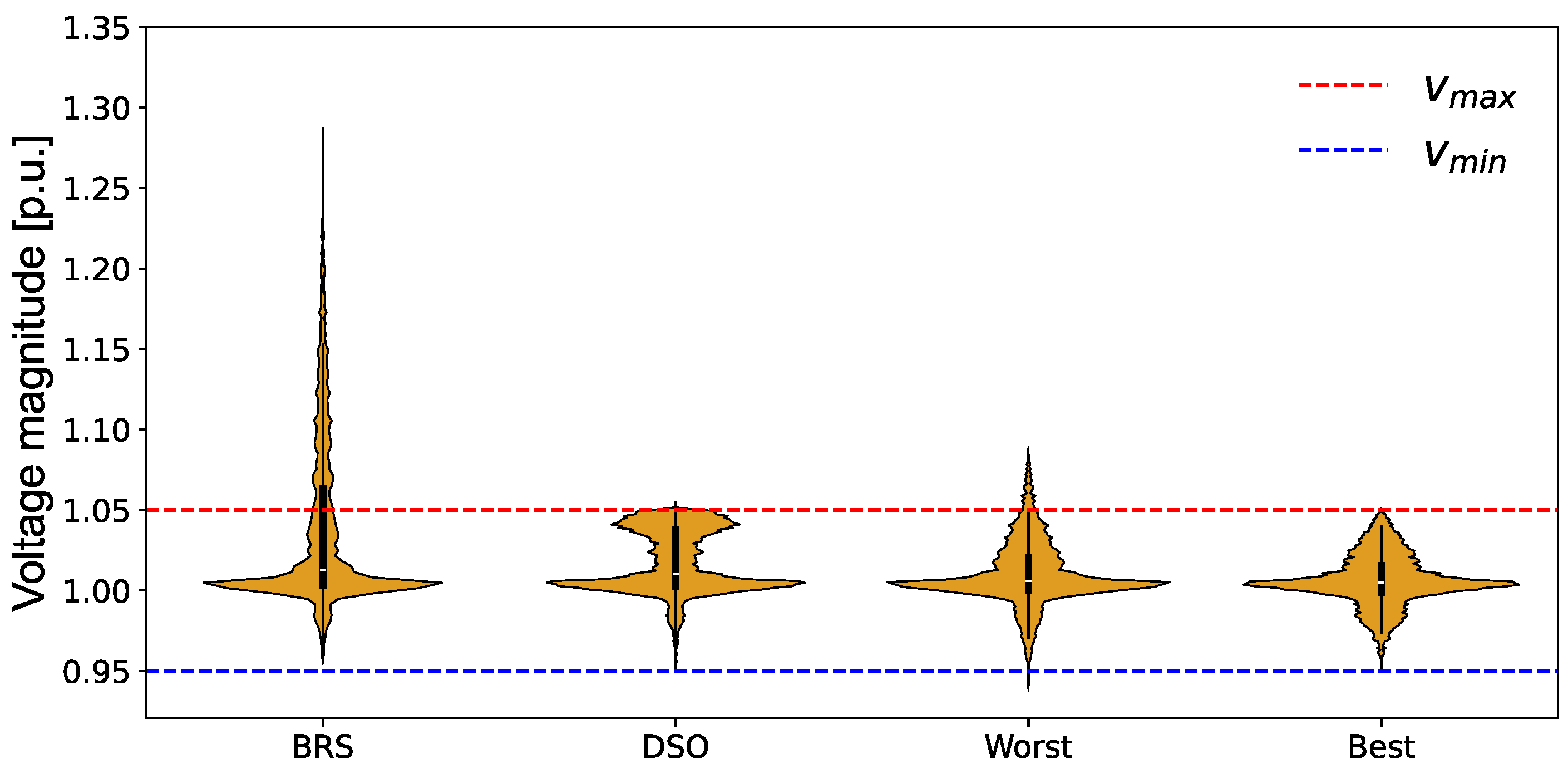

To give an idea of the entity of violations, violin plots are used in

Figure 6, showing the per-unit distribution of the magnitude of the nodal voltages for the solution obtained with worst and best samples generated by Monte Carlo.

The total violation of voltages was solved in the best-case sample. Although the worst-case sample leads to few unsolved voltage violations, the under-/over-voltage values reached at the end of VI-Control are significantly lower compared to the BRS. In addition, the maximum and minimum values reached in the worst case (

and

p.u., respectively) are still largely within the security limits of

set by the current normative on the quality of supply (e.g., EN 50160 [

35]).

When comparing the voltage distributions, it is easy to notice that in the solution obtained by VI-Control, voltages are mostly concentrated around the per unit value, while in the DSO-Control, including voltage constraints, the solution leads to more values closer to the upper limit of p.u.

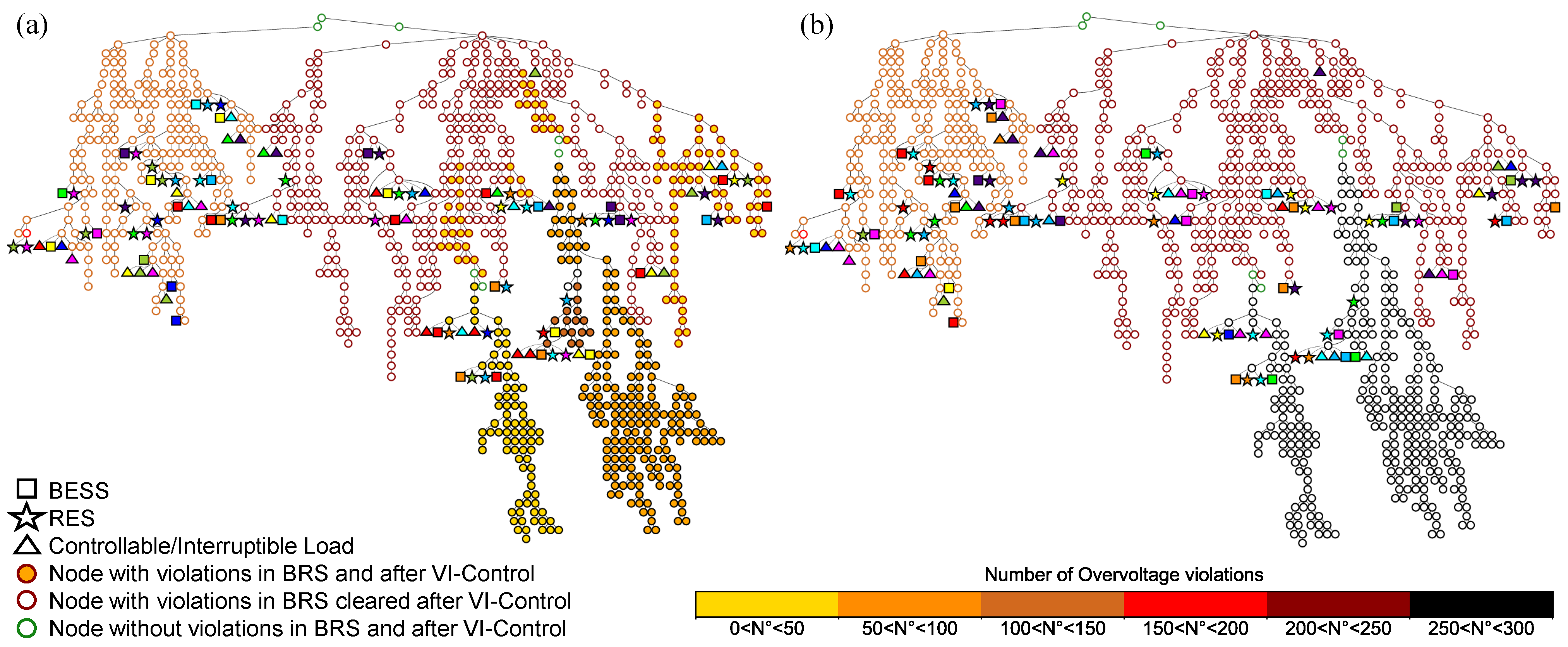

The association of DERs with RECs obtained with the worst and best sample is depicted in

Figure 7, where the color of each DER indicates the associated REC.

In the BRS, almost all nodes in the DN are affected by numerous voltage violations during the simulation period (colored dot contour). It can be seen that in the worst sample (

Figure 7a), the distribution of DERs belonging to the same REC is more scattered around the DN. Despite this, once VI-Control is performed, the majority of violations are cleared in several nodes, as previously discussed (more than 88%). Considering unsolved violations, few of them are experienced in nodes where connected DERs belong to the same REC and are close to each other (gold dots). However, more unmitigated violations persist in nodes where the nearby connected resources belong to different RECs, leading to a limited effect achieved by the VI condition (darkorange dots). This is also due to the fact that in some RECs, the total RES generation is often comparable to the total demand during the simulation period; thus, there is no need to significantly increase the demand of the relative BESS/DR to match the RES output. The VI-Control performed with the best sample (

Figure 7b) was able to solve all initial violations (like the ideal DSO-Control).

4.2. Case B: VI-Control of 10 RECs with Sensitivity Signals

The adoption of sensitivity signals in the execution of VI-Control leads to further improvements, as shown in

Table 4 and

Table 5.

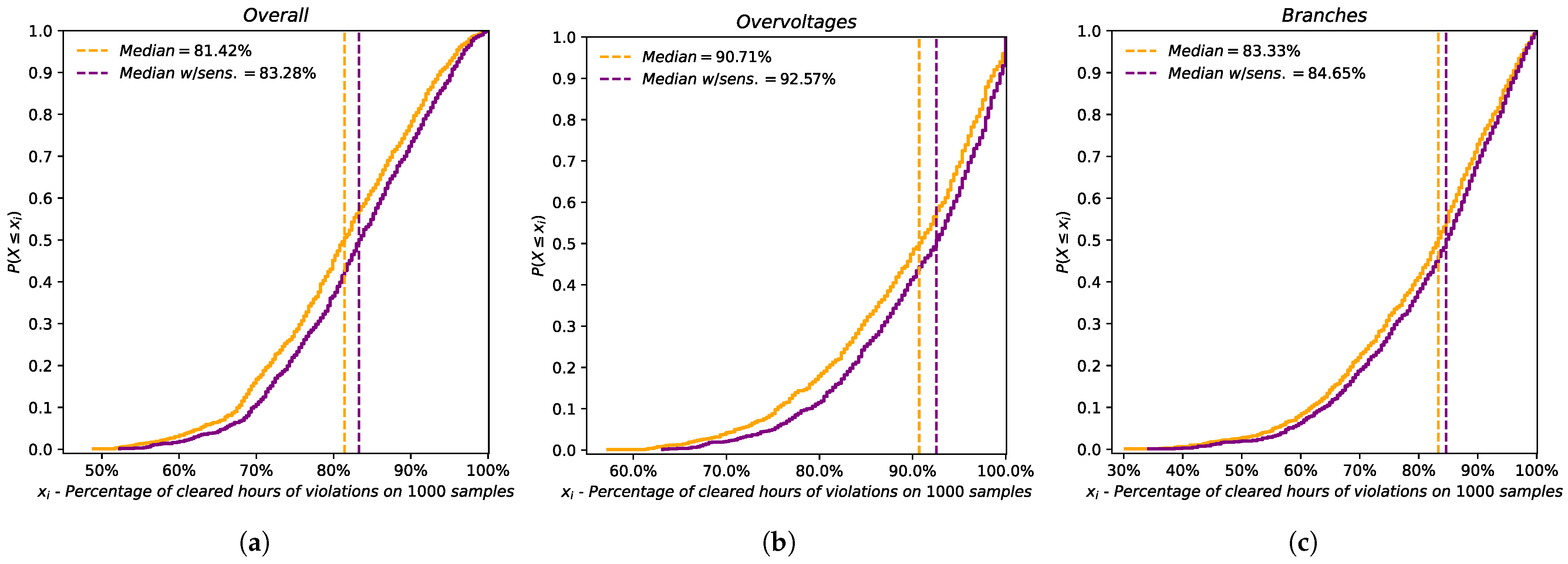

In addition, looking at the cumulative distribution shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, some outliers have been corrected, increasing their relative percentage reductions in mitigated violations.

As can be seen, the correct use of flexible resources is observed with a further reduction in terms of violations. In particular, the control signals enable implementing better improvements considering the lower number of hours with violations that arenot mitigated, especially with overvoltage violations.

4.3. Case C: Results with Different Numbers of Controlled RECs

This test case is introduced to evaluate how VI control performs if the same number of DERs is split among a lower or higher number of RECs. The test results were obtained by applying the same approach previously described but adopting a different parameter

. Two more cases were studied, namely,

and

. As before, for each case, 1000 random samples were used to analyze the VI-Control response. The results are shown in the

Table 6 and

Table 7, which also allow a comparison with previous tables (

) (

Table 2 and

Table 3).

The test results showed that an increase in the number of controlled RECs would generally increase the total number of cleared violations. Also, the number of hours with residual violations decreased when . The opposite statement is also true, since the VI-control performed worse with a lower number of RECs. The number of controlled RECs, , cannot be increased indefinitely. A very high count increases the likelihood of selecting highly uneven aggregations of DERs (for example, RECs without sufficient resources to achieve the VI target).

4.4. Computational Performances

This section allows an assessment of the performance of the testing algorithm used to obtain numerical results. Although the algorithm was designed for offline analysis and the emulation of VI-Control, the running times are reported for completeness and to offer a measure of computational loads for potential future applications.

The comparative results between DSO-Control and VI-Control optimization problems are shown in

Table 8. The metrics shown represent overall computation or average performance with respect to a single REC configuration sample or a single snapshot (a single operating point characterized by security violations). Please note that operating points without violations do not trigger any optimizations and are skipped by the algorithm. An entire month of operation, characterized by 323 h with security violations, is solved quite rapidly (half an hour when a full DOPF formulation is adopted). Each Monte Carlo simulation employed about 3–4 days. It can be observed that the time needed by the Monte Carlo does not grow proportionally to

, because the dimension of the subproblems decreases with

and because of the time needed to solve the AC load flow at the end of each optimization. The full DOPF problem converges averagely in 6–7 iterations, whereas VI subproblems converge in around 4–5 iterations. All simulations were performed on a computer with 32 GB of RAM and 12th Gen Intel

® Core™ i9-12900F CPU @ 2.40 GHz.

5. Conclusions

This paper showed how a simple decentralized control strategy of flexible resources can help a DSO in alleviating most operating security violations in a scenario of high-penetration renewable distributed generation. The control strategy relies on the inherent control capability within renewable energy communities (RECs). The strategy, called Virtual Islanding (VI), allows the achievement of short-term net-zero exchanges among the resources of each REC participating in this control. VI can be requested as a service by the DSO whenever security violations are detected or forecasted in the near future.

The effectiveness of the VI-Control strategy was demonstrated in this study through a comparison with an ideal centralized DSO-Control. The results were obtained, associating flexible resources to the RECs with purely random criteria and avoiding any possible bias due to the choice of a specific configuration.

The aggregated results showed that the VI-Control allowed, with 95% confidence, the elimination of 94% of all security concerns across an entire observation window. Even in the worst (random) scenarios, voltage profiles were significantly improved, staying within the the limits imposed by the current normative on the quality of supply. The best scenarios even led to the same result obtained with the ideal centralized control solution.

The proposed VI-Control shows great potential thanks to its simplicity. No knowledge of the grid is required for the agents responsible for this control, which can be operated in real time, employing the same monitoring and control architecture used by RECs to manage internal energy balance. VI-Control permits the avoidance of islanding (virtual, not physical islanding), improving its actual applicability to RECs, which might have flexible resources scattered around the network and connected to different secondary substations or feeders. The results showed in this paper proved VI’s effectiveness regardless of the localization of the resources within each REC.

A valuable future application of the VI paradigm is enabling (quasi) real-time energy balance control. Assuming the use of flexible resources with rapid response characteristics, such as BESSs, the VI concept allows each REC to act as a self-regulating entity. This enables the REC to dynamically compensate for all energy fluctuations (both from its own loads and generators) instantly. The goal is to achieve a state of real-time energy neutrality, shifting the responsibility of immediate balancing from the central grid to the local community level. Further developments will be devoted to the identification of tools and methods to enable this kind of control at end-user levels on several types of DERs. Specifically, a two-layer architecture could be considered, where the upper level aims to optimize the use of flexible resources based on forecasts, while the lower level operates in real time to compensate for fluctuations in demand and renewable energy generation.

The practical applicability of VI control to distribution systems relies, of course, on improvements in policies and grid codes and the deployment of suitable automation technologies at the REC level. The most recent and relevant development in the Italian normative is the introduction of Central Plant Controllers (CPCs) in the MV grid code [

36]. CPCs are mandatory for active users connected at MV level, allowing observability, coordinating multiple DERs, and providing grid regulation services. CPCs are already currently under deployment and are commercially available products. Expanding the functionalities of this technology for aggregator and REC application frameworks is readily achievable.