Research on High-Frequency Impedance Characteristics of Damaged Circuit Breaker Closing Resistance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Simulation Results of the Damaged Closing Resistor

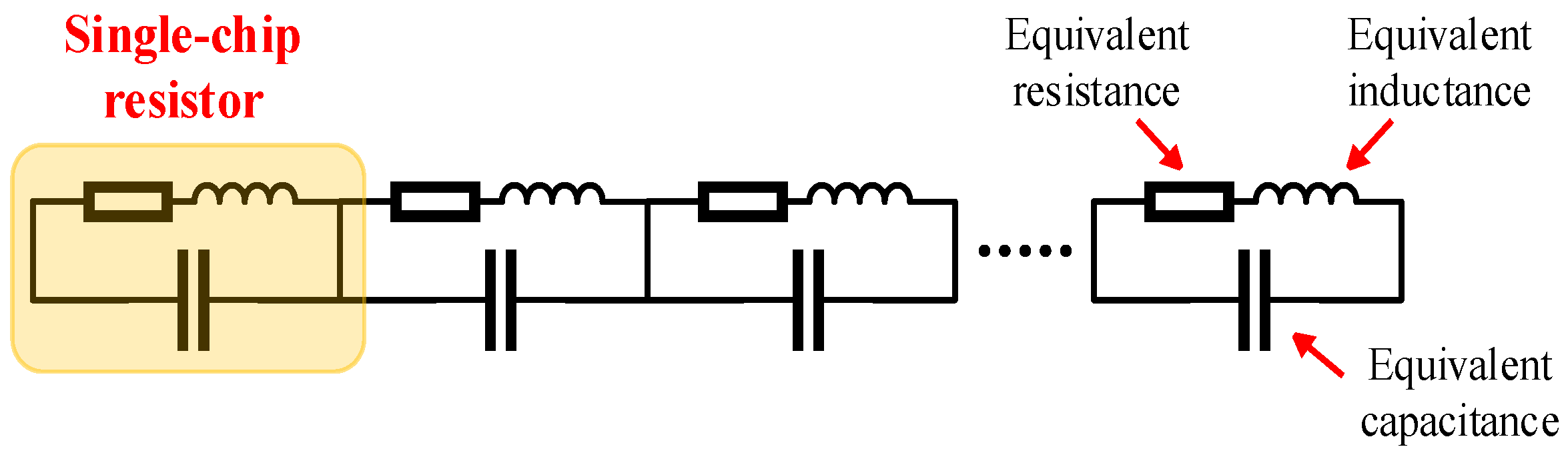

2.1. Simulation Model

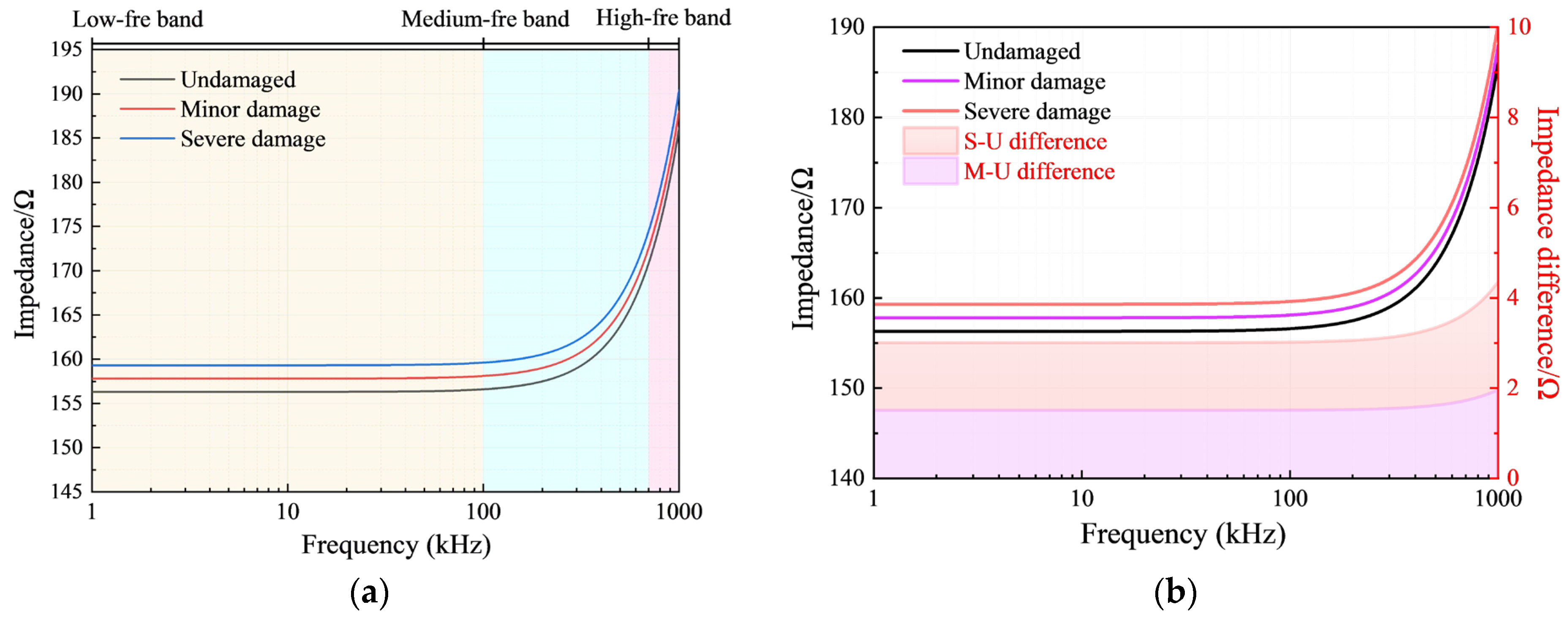

2.2. Edge Drop Damage

2.3. Entire Crack Damage

2.4. Blackened and Charred Damage

3. On-Site Test Results of the Damaged Closing Resistor

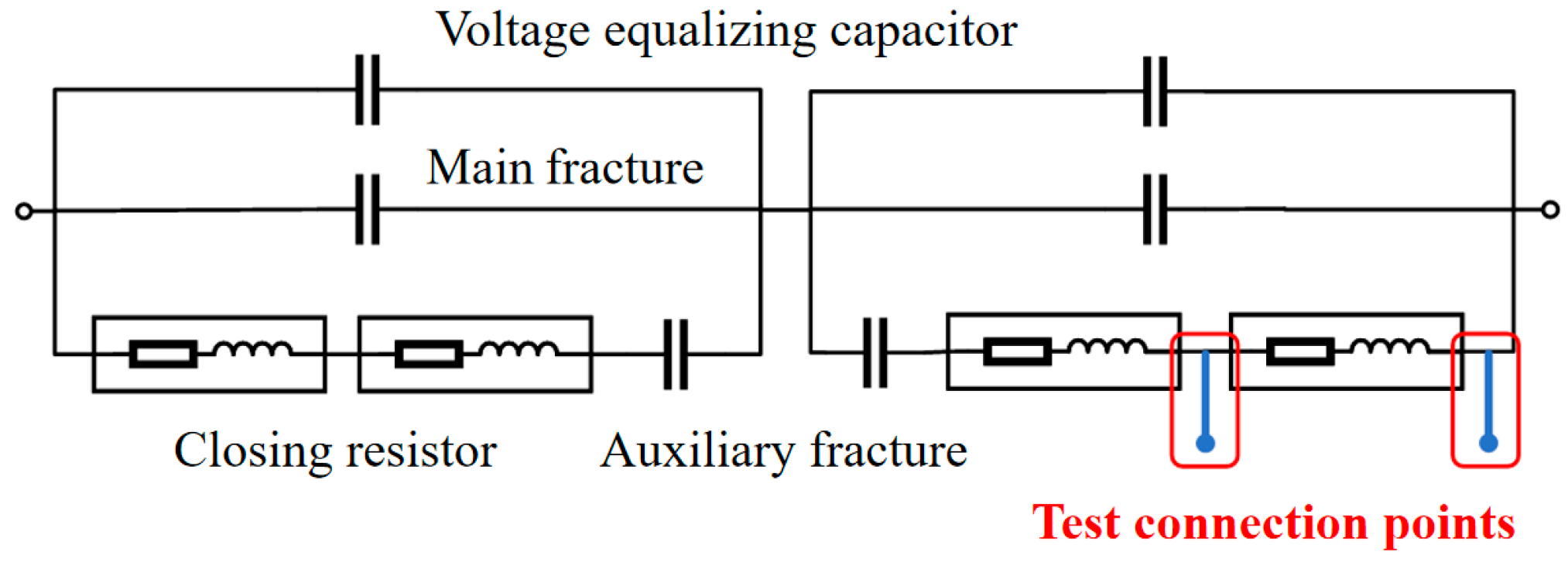

3.1. Wiring Method for Entity Detection

3.2. Simulation of the Damage Condition of the Closing Resistor

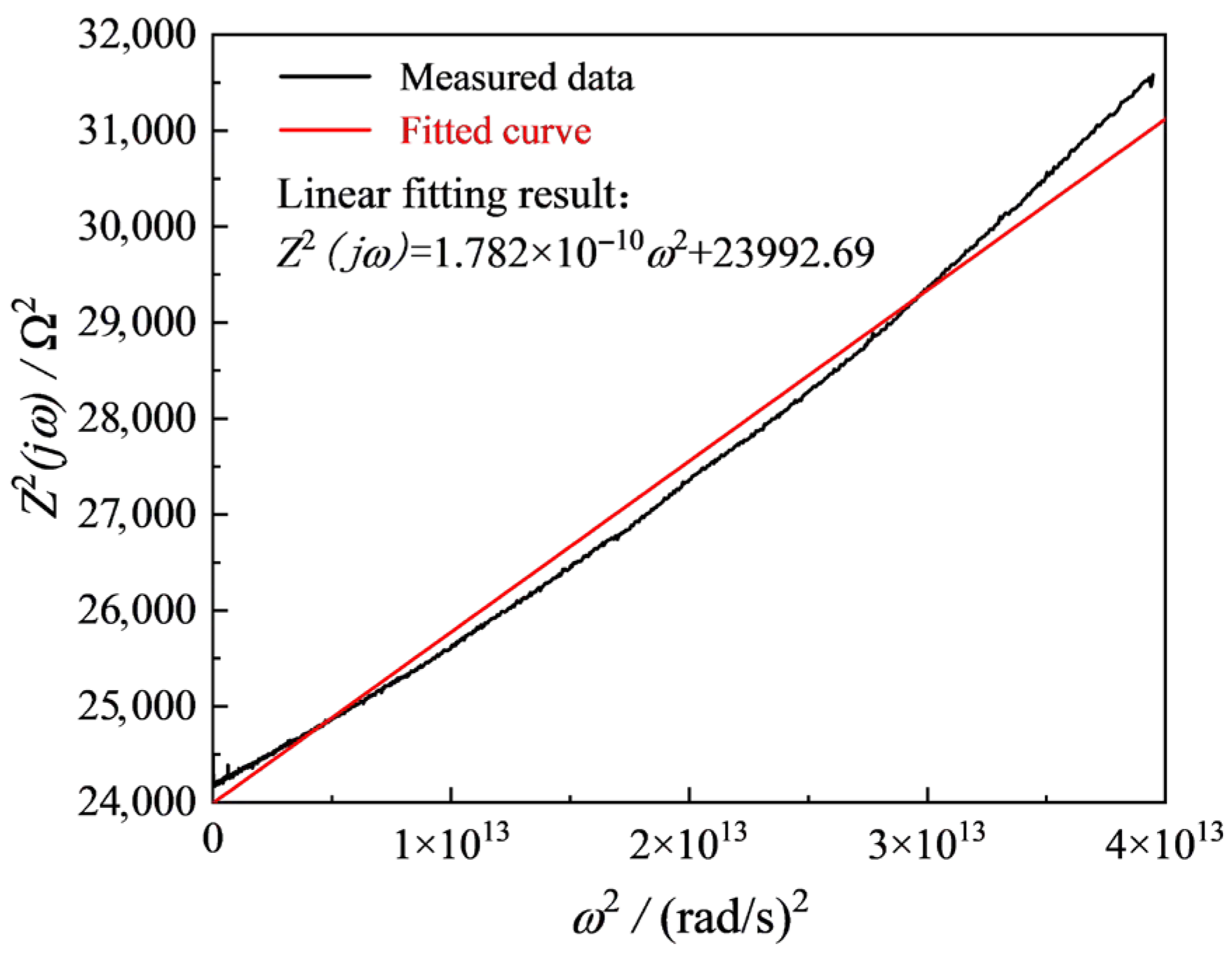

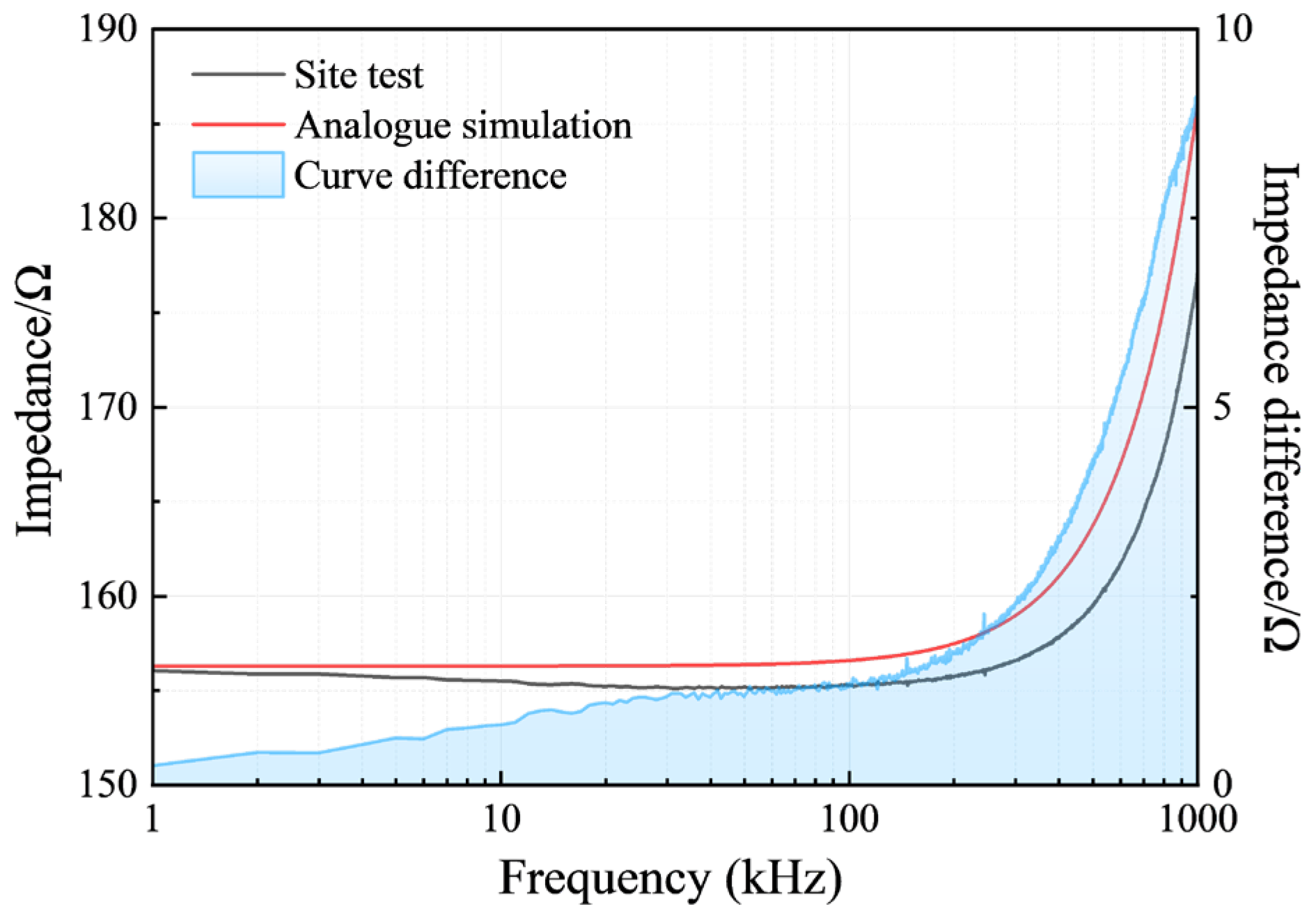

3.3. Test Results of Closing Resistance

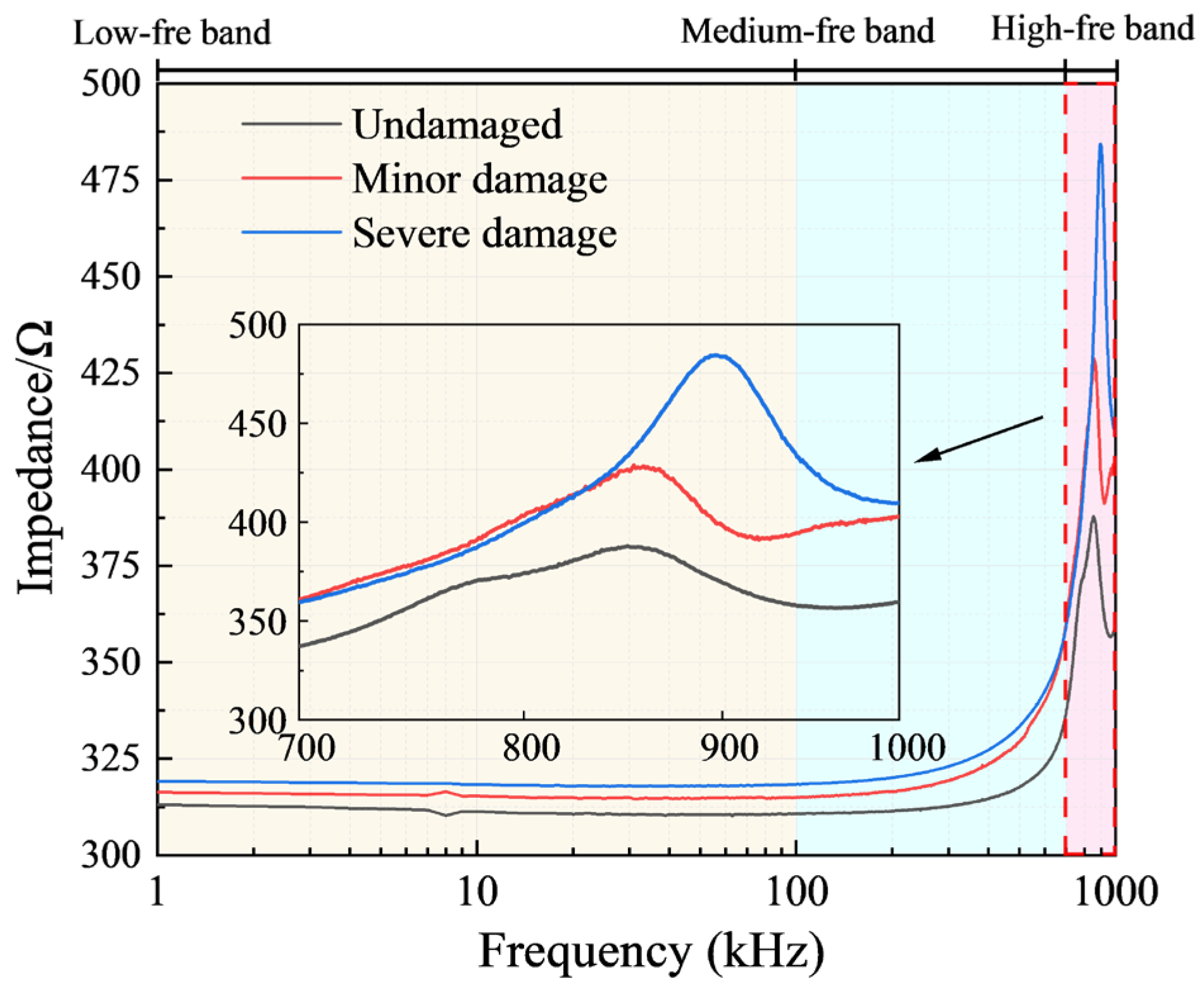

3.4. Test Results of the Closing Resistor in the Tank

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- For the three classical damage types of the closing resistor, the variation trends of the curves under different damage degrees and the trends in the impedance differences before and after damage are fundamentally consistent, with all cases exhibiting overall resistive and inductive characteristics. When damage occurs, both the equivalent resistance and inductance increase, further demonstrating that the more severe the damage, the more significant the increase.

- (2)

- The frequency-impedance curve obtained from measurements performed on the closing resistor assembly inside the tank exhibits resistive characteristics in the low-frequency segment and reactive characteristics in the high-frequency segment. Moreover, variations in the inductance properties of the closing resistor caused by different degrees of damage demonstrate superior sensitivity and significance compared to changes in resistance. Therefore, inductive characteristics can serve as an effective indicator for identifying the damage state of closing resistors, providing an experimental basis and methodological support for reliable damage detection in subsequent research.

- (3)

- Based on the variation patterns observed in the sweep-frequency impedance curve, we have developed a foundational approach for establishing a standard to diagnose the degradation level of closing resistors using the sweep-frequency impedance method. This approach is based on a combined assessment of the mean value shift in the low-frequency band, and the resonance point shift in the high-frequency band.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Niu, B.; Ma, F.; Xiang, Z.; Wu, H.; Sun, S.; Wen, Q. Research on operation reliability and fault diagnosis technology of pre-insertion resistors for circuit breakers. Ningxia Electr. Power 2021, 1, 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Legate, A.C.; Brunke, J.H.; Ray, J.J. Elimination of closing resistors on EHV circuit breakers. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 1988, 3, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Li, W.; Lu, W.; Zhang, C.; Chen, W.; Zhou, H. Simulation of radial breakdowns on the breaker grading capacitor of 500 kV AC filter. High Volt. Appar. 2018, 54, 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, R.; Yi, Q.; Su, F.; Sun, K.; Chen, J.; Zhou, H. Study on applicability of circuit breaker closing resistance in EHV and UHV AC systems. Power Syst. Technol. 2011, 35, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; He, C.; Deng, J.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, G.; Ni, H.; Ma, F.; Chen, L. Energization transient suppression of 750 kV AC filters using a pre-insertion resistor circuit breaker with a controlled switching device. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2022, 37, 3381–3390. [Google Scholar]

- Awad, E.A.; Badran, E.A.; Youssef, F.M.H. Mitigation of temporary over-voltages in weak grids connected to DFIG-based wind farms. J. Electr. Syst. 2014, 10, 431–444. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Tu, Y.; Fu, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Zhou, J. Fracture analysis of fastening bolt of closing resistance for 1100 kV GIS circuit breaker. Zhejiang Electr. Power 2023, 42, 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, S.; Ruan, J.; Huang, D.; Wu, G.; Liu, B.; Zhang, K. Dynamic voltage-sharing measures for vacuum circuit breakers with triple breaks. Power Syst. Technol. 2012, 36, 252–259. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Lv, D.; Zhang, F. Study on the suppression efficacy of filter closing inrush currents by shunt dynamic closing resistor of circuit breaker. Power Syst. Technol. 2024, 48, 3931–3937. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, G.; Liu, K.; Wang, Y.; Gao, L. Adaptability of cancellation of the closing resistance of circuit breaker for 330 kV transmission line. Insul. Surge Arresters 2023, 6, 165–171. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Bhargava, P. Fabrication of low specific resistance ceramic carbon composites by colloidal processing using glucose assoluble carbon source. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2017, 40, 1197–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, X.; Wei, Y.; Wu, C.; Deng, J.; Ma, F. Study of controlled switching with pre-insertion resistor during energization of AC filters. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Symposium on High Voltage Engineering (ISH 2021), Hybrid Conference, Xi’an, China, 21–26 November 2021; pp. 1682–1687. [Google Scholar]

- Lazimov, T.; Saafan, E.A.; Babayeva, N. Transitional processes at switching-off capacitor banks by circuit-breakers with pre-insertion resistors. In Proceedings of the 2015 Modern Electric Power Systems (MEPS), Wroclaw, Poland, 6–9 July 2015; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hedman, D.E.; Johnson, I.B.; Titus, C.H.; Wilson, D.D. Switching of Extra-High-Voltage Circuits II-Surge Reduction with Circuit-Breaker Resistors. IEEE Trans. Power Appar. Syst. 1964, 83, 1196–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Chen, L.; Wu, X.; Ni, H.; Zhang, Q.; Wei, Y. Fault analysis of pre-insertion resistors for circuit breakers used in 750kV ACF. In Proceedings of the 16th IET International Conference on AC and DC Power Transmission (ACDC 2020), Online Conference, 2–3 July 2020; pp. 283–289. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, F.; He, C.; Chen, X.; Zhu, X.; Deng, J.; Ni, H. Suppression Methods of 750 kV AC Filter Switching Inrush Surge for Circuit Breakers Having Pre-insertion Resistors. In Proceedings of the 2020 4th International Conference on HVDC (HVDC), Xi’an, China, 6–9 November 2020; pp. 1207–1212. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, K.A.; Bhalja, B.R.; Parikh, U.B. Evaluation of controlled energisation of an unloaded power transformer for minimizing the level of inrush current and transient voltage distortion using PIR-CBs. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2018, 12, 2788–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Y.; Bao, Y.; Wu, X.; Qiu, Z.; Li, S.; Guo, L. Study on the Dynamic Resistance Characteristic of Circuit Breaker Closing Resistor Under Impulse Current. In Proceedings of the 2025 7th International Conference on Energy Systems and Electrical Power (ICESEP), Wuhan, China, 20–22 June 2025; pp. 1206–1211. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, F.; Li, A.; Niu, B.; Ni, H.; Liu, B.; Deng, J. Extra/Ultra High Voltage AC Filter Circuit Breaker Pre-Insertion Resistors State Evaluation Based on Wavelet Decomposition and TLS-ESPRIT. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Energy Engineering and Power Systems (EEPS), Hangzhou, China, 9–11 August 2024; pp. 1016–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Li, H.; Xu, Y.; Xia, H. Analysis on a fault of grading capacitor for 500 kV circuit breaker. High Volt. Appar. 2016, 52, 195–199. [Google Scholar]

- Patcharoen, T.; Ngaopitakkul, A. Transient inrush current detection and classification in 230 kV shunt capacitor bank switching under various transient-mitigation methods based on discrete wavelet transform. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2018, 12, 3718–3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Yin, F.; Chang, Y.; Tang, W.; Wei, J. Research of closing resistor in 800 kV SF6 tank circuit breaker. High Volt. Appar. 2020, 56, 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Han, B.; Chen, W.; Chen, X.; Ban, L.; Xiang, Z.; Ge, D. Study on Eliminating Closing Resistor of Circuit Breaker by Using Controllable Surge Arrester in UHV System. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Power System Technology (POWERCON), Guangzhou, China, 6–8 November 2018; pp. 2839–2844. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Dai, H.; Chen, W.; Cui, B.; Yang, F.; Yao, X. Energy Tolerance and Failure Characteristics of Carbon-ceramic Closing Resistor for Circuit Breaker. High Volt. Eng. 2024, 50, 2590–2600. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Wen, D.; Bao, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Li, S.; Ji, S. Stress distribution numerical simulation and influencing factor analysis of stress under operating shock of pre-insertion resistor of 750 kV dead tank circuit breaker. High Volt. Appar. 2023, 59, 180–185. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, L.; Hao, X.; Chen, Q. Anti-sweep jamming method for FM fuze based on outlier reconstruction. J. Beijing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 2025, 51, 1377–1384. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; Xia, C.; Wang, X.; Tong, W. Coupling error coefficient identification based on swept-frequency measurement in MEMS gyroscopes. J. Chin. Inert. Technol. 2024, 32, 170–179. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Chen, P.; Yang, L.; Han, T.; Tang, Y.; Chen, C.; Ding, Z. A machine learning approach to correct imaging distortions in swept-source optical coherence tomography. Acta Phys. Sin. 2025, 74, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Degree of Damage | Resistance/Ω | Inductance/μH |

|---|---|---|

| Undamaged | 156.3 | 13.30 |

| Minor damage | 157.8 | 13.45 |

| Severe damage | 159.3 | 13.71 |

| Degree of Damage | M-South | M-North | N-South | N-North |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Undamaged | 156.4 Ω | 155.6 Ω | 156.5 Ω | 156.3 Ω |

| Minor damage | 157.7 Ω | 157.6 Ω | 157.8 Ω | 157.8 Ω |

| Severe damage | 158.4 Ω | 158.8 Ω | 158.6 Ω | 159.3 Ω |

| Degree of Damage | Resistance/Ω | Inductance/μH |

|---|---|---|

| Undamaged | 154.89 | 13.30 |

| Minor damage | 155.72 | 13.42 |

| Severe damage | 156.90 | 13.51 |

| Degree of Damage | Undamaged | Minor Damage | Severe Damage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resonant frequency | 869 kHz | 854 kHz | 897 kHz |

| Resonant point impedance | 421.44 Ω | 478.84 Ω | 534.39 Ω |

| Degree of Damage | Resonance Point Shift Ratio r1, r2 Initial Value Change Ratio r |

|---|---|

| Severe damage | r1 ≥ 5% or r2 ≥ 20% or r ≥ 15% |

| Moderate damage | 2% ≤ r1 ≤ 5% or 10% ≤ r2 ≤ 20% or 10% ≤ r ≤ 15% |

| Minor damage | 1% ≤ r1 ≤ 2% or 5% ≤ r2 ≤ 10% or 7.5% ≤ r ≤ 10% |

| Undamaged | r1 ≤ 1% and r2 ≤ 5% and r ≤ 7.5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, C.; Niu, B.; Ma, F.; Yin, L.; Sun, S.; Han, X. Research on High-Frequency Impedance Characteristics of Damaged Circuit Breaker Closing Resistance. Energies 2025, 18, 5768. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215768

Zhang C, Niu B, Ma F, Yin L, Sun S, Han X. Research on High-Frequency Impedance Characteristics of Damaged Circuit Breaker Closing Resistance. Energies. 2025; 18(21):5768. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215768

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Ce, Bo Niu, Feiyue Ma, Lingjun Yin, Shangpeng Sun, and Xutao Han. 2025. "Research on High-Frequency Impedance Characteristics of Damaged Circuit Breaker Closing Resistance" Energies 18, no. 21: 5768. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215768

APA StyleZhang, C., Niu, B., Ma, F., Yin, L., Sun, S., & Han, X. (2025). Research on High-Frequency Impedance Characteristics of Damaged Circuit Breaker Closing Resistance. Energies, 18(21), 5768. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215768