Study on Superconducting Magnetic Energy Storage for Large Subway Stations with Multiple Lines

Abstract

1. Introduction

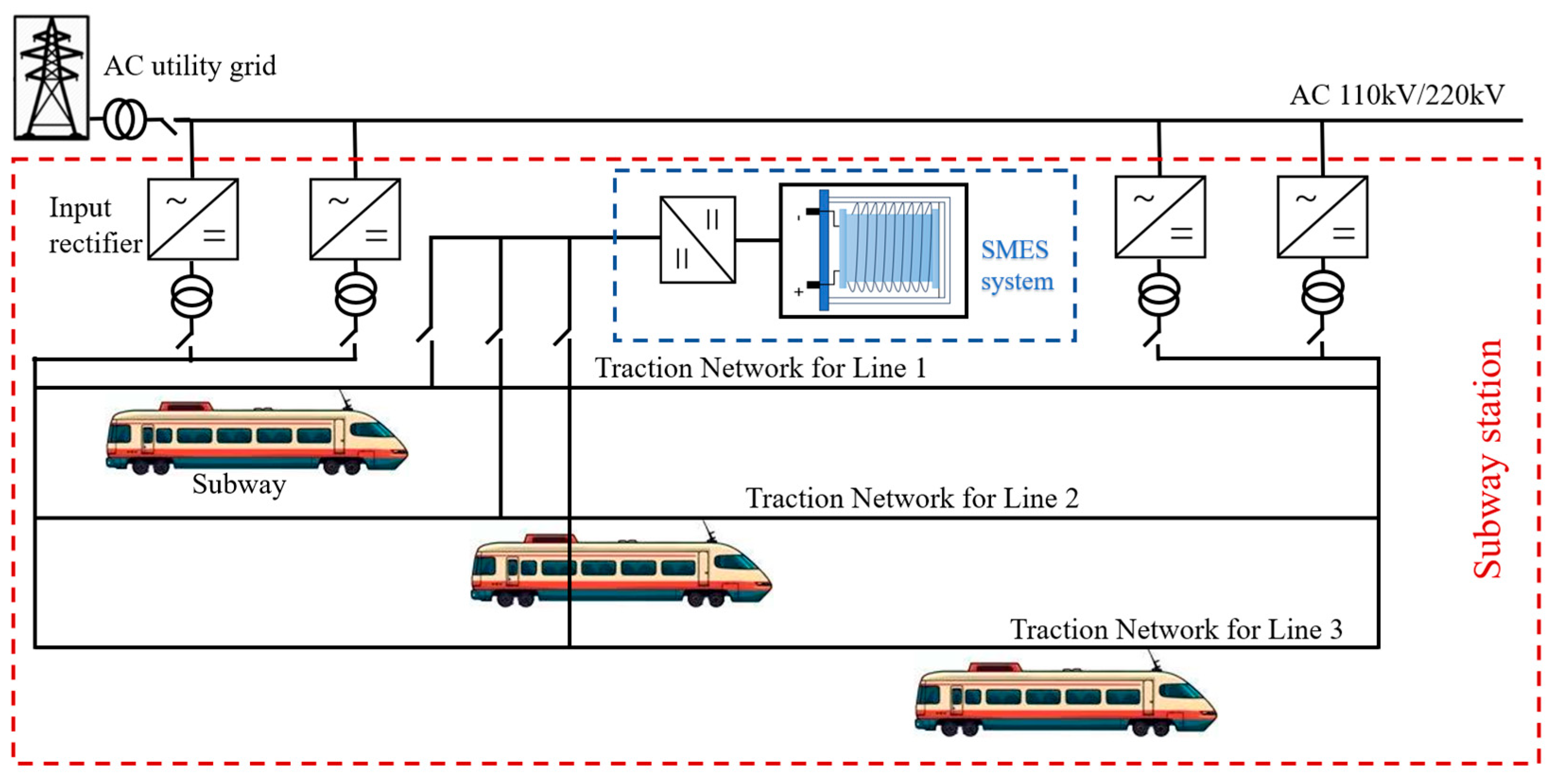

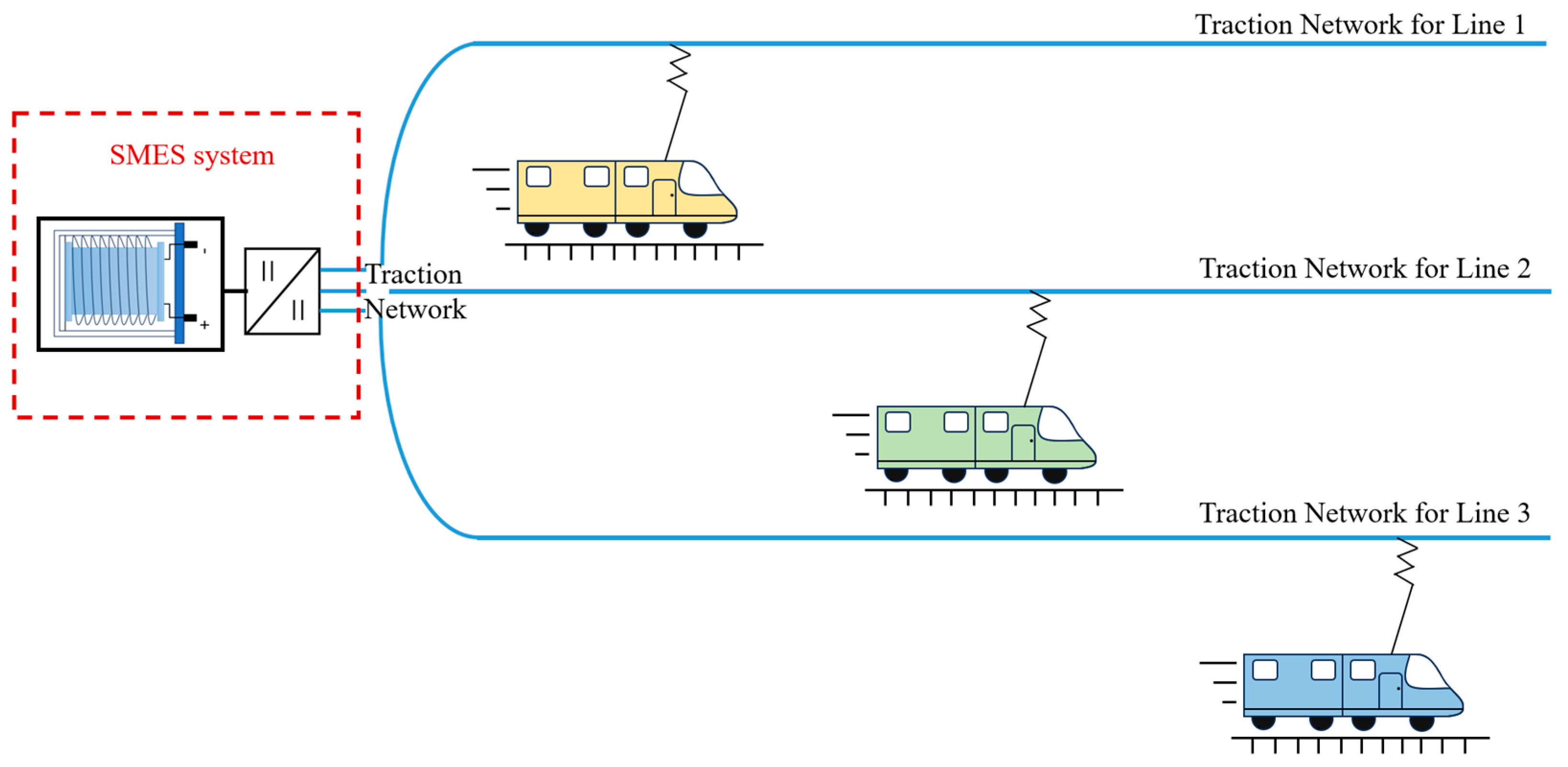

2. SMES for a Large Subway Station with Multiple Lines

3. SMES Voltage Compensation Principle

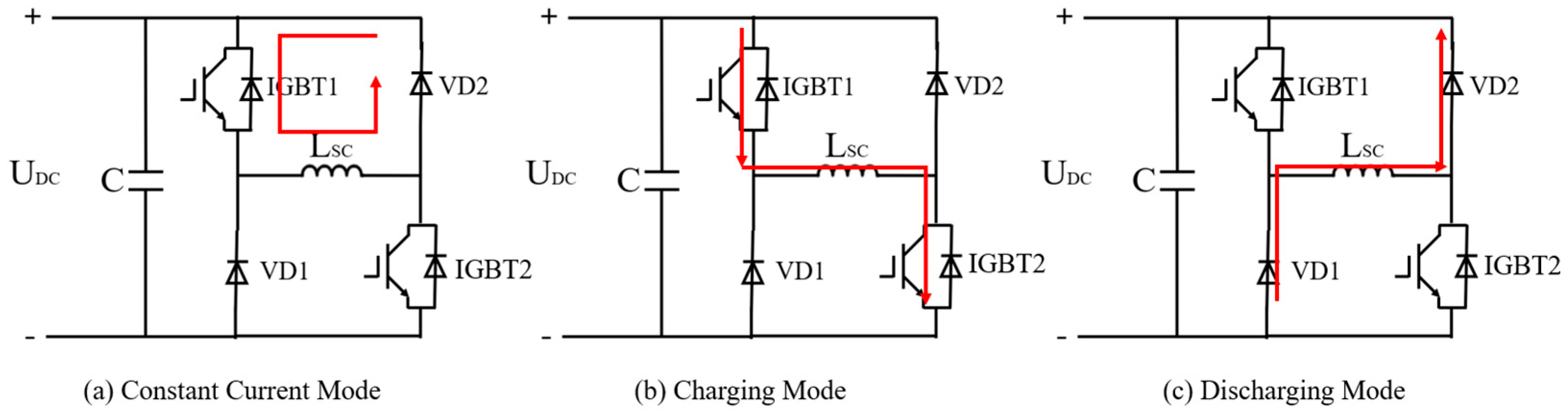

- (1)

- IGBT1 and VD2 are conducting, while IGBT2 and VD1 are off. The freewheeling current (isc) forms a circulating loop through IGBT1—Lsc—VD2. When switching device losses are neglected, isc remains constant, and the energy stored in Lsc remains unchanged. At this point, the DC/DC converter operates in freewheeling mode.

- (2)

- IGBT1 and IGBT2 are both on, while VD1 and VD2 are off. The system charges Lsc through the path IGBT1—Lsc—IGBT2. When switching device losses are negligible, isc increases, and the energy stored in Lsc rises. At this point, the DC/DC converter operates in charge mode.

- (3)

- IGBT1 and IGBT2 turn off simultaneously, while VD1 and VD2 turn on. Lsc discharges energy through the path VD1—Lsc—VD2—C, then through the converter to the system. The current isc decreases, and the energy stored in Lsc decreases. At this point, the DC/DC converter operates in a discharge state.

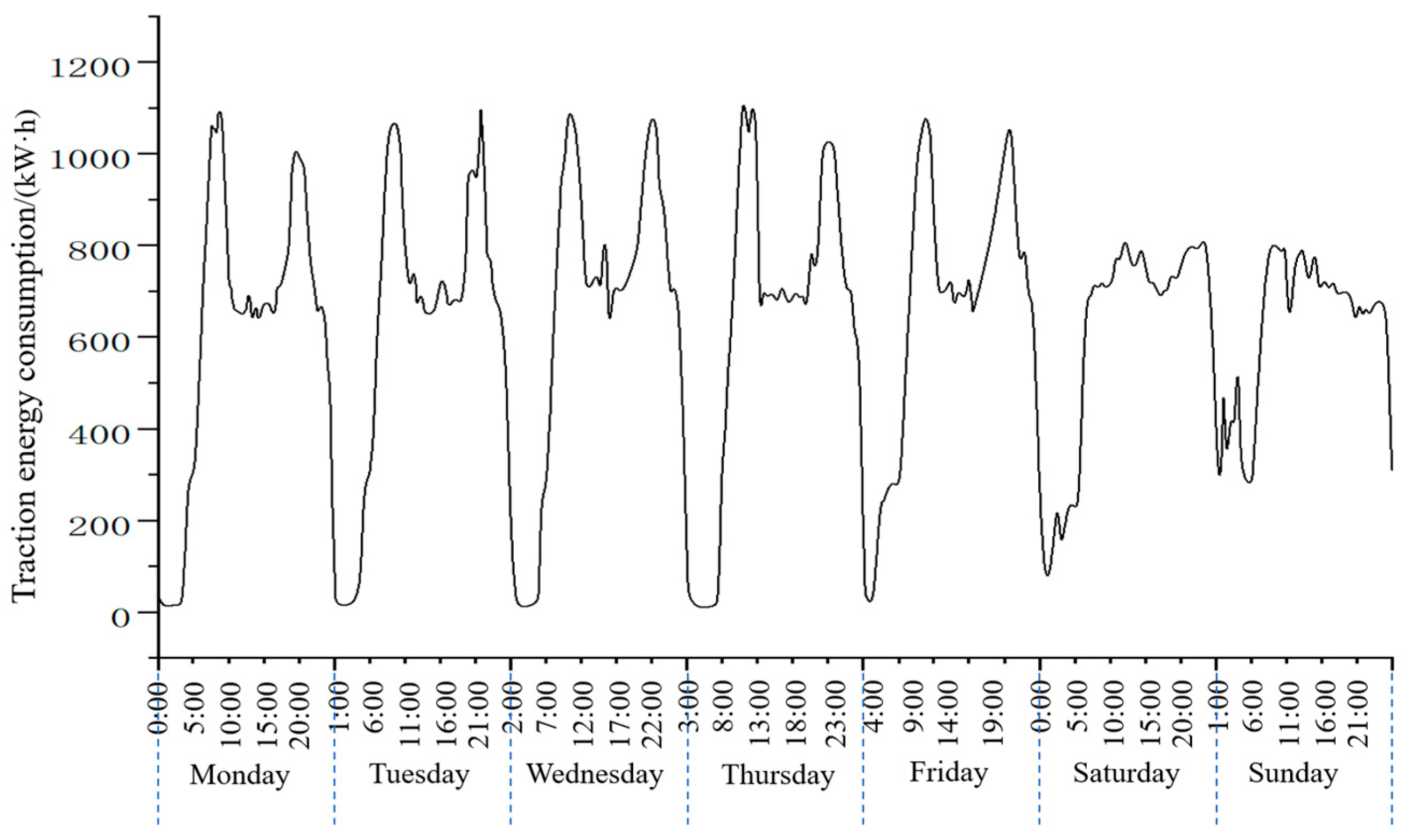

4. Simulation and Analysis of Superconducting Energy Storage Devices

4.1. Simulation Environment

4.2. Single-Line Study

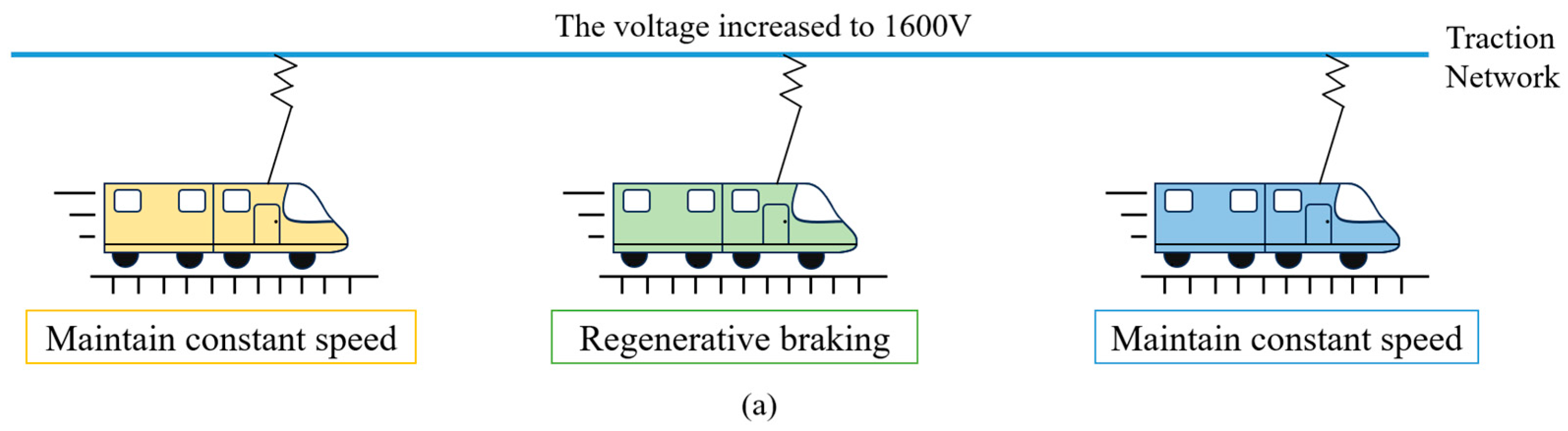

4.2.1. Different Scenarios of Single-Line Operation

- (1)

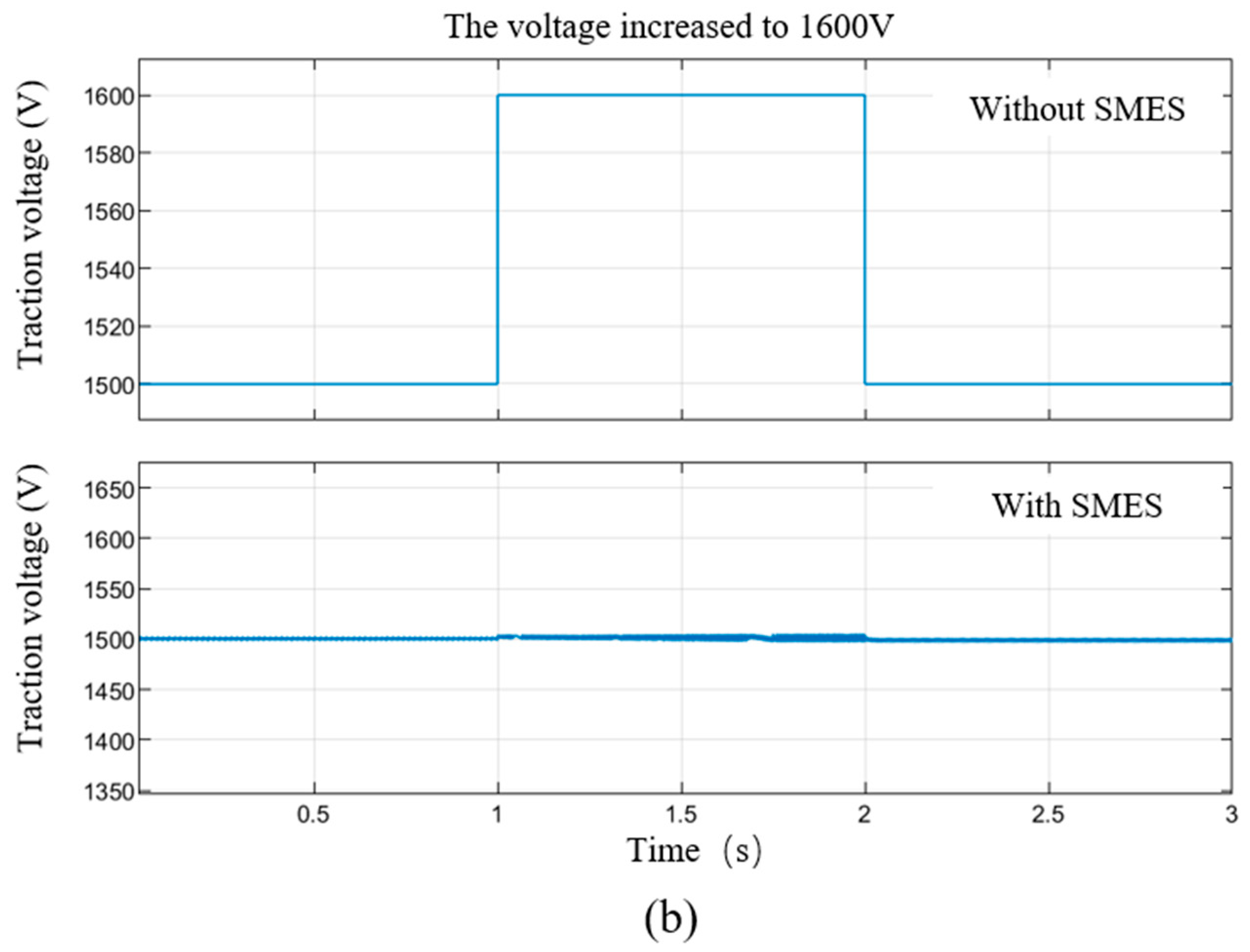

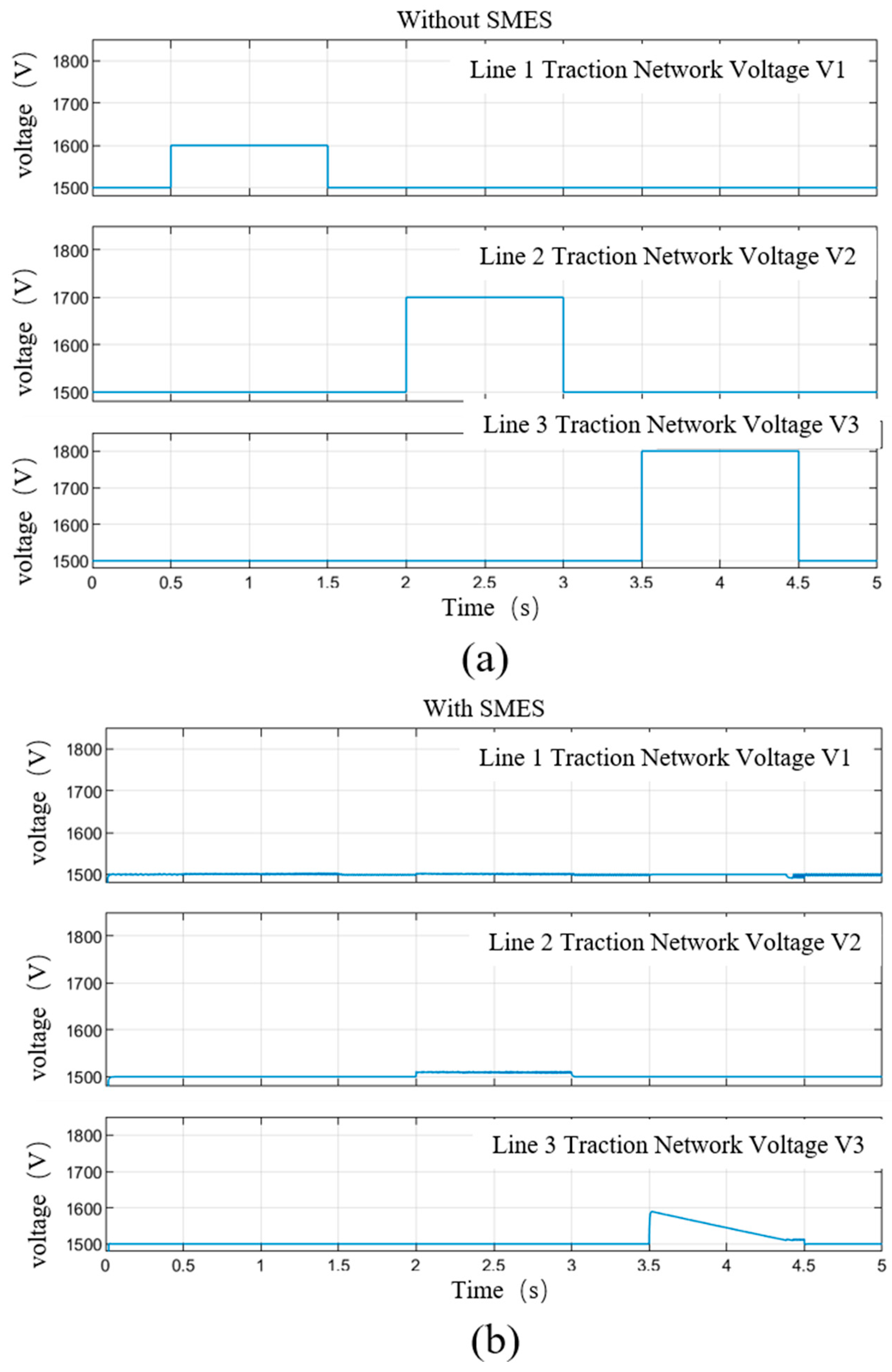

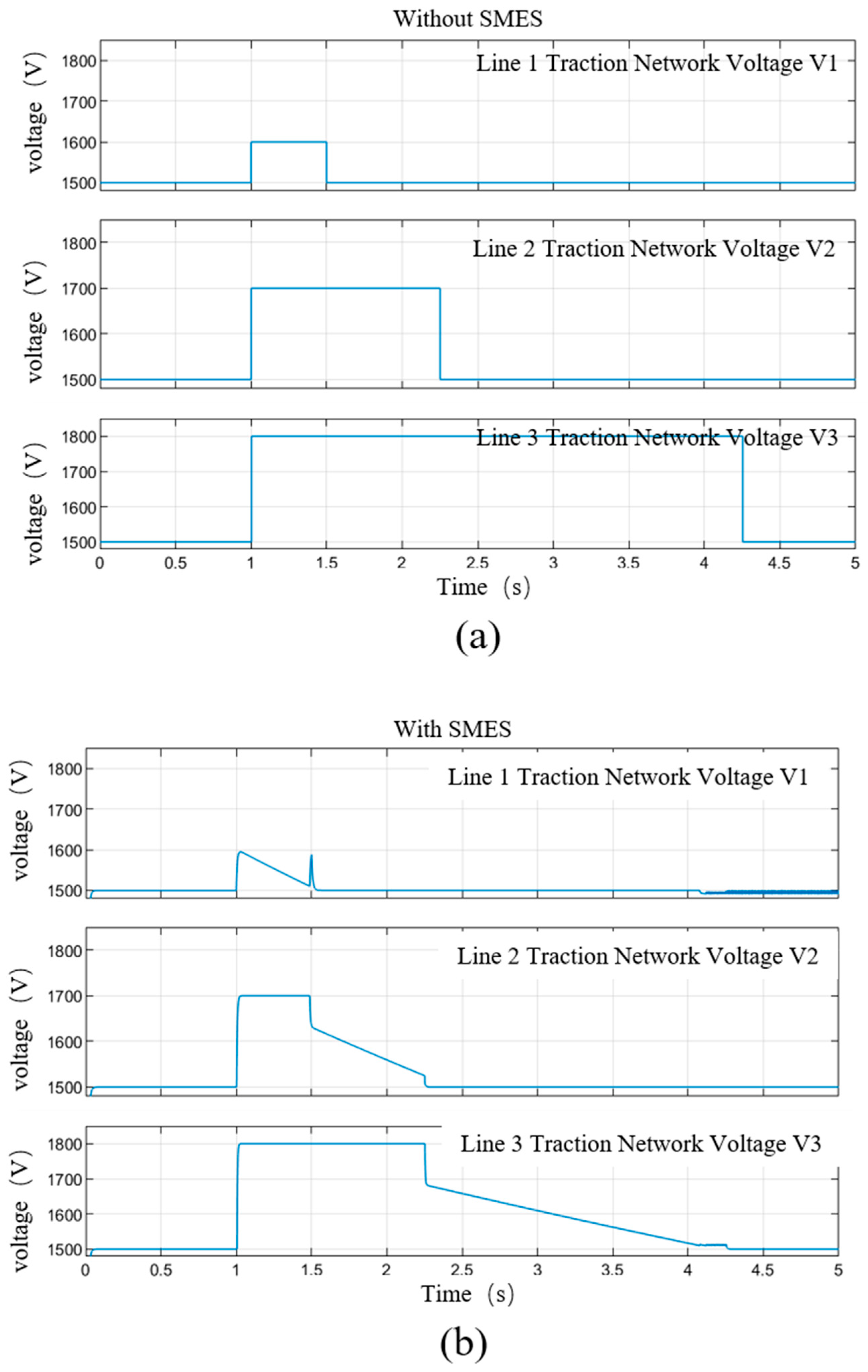

- Simulation Results for Traction system voltage increase

- (2)

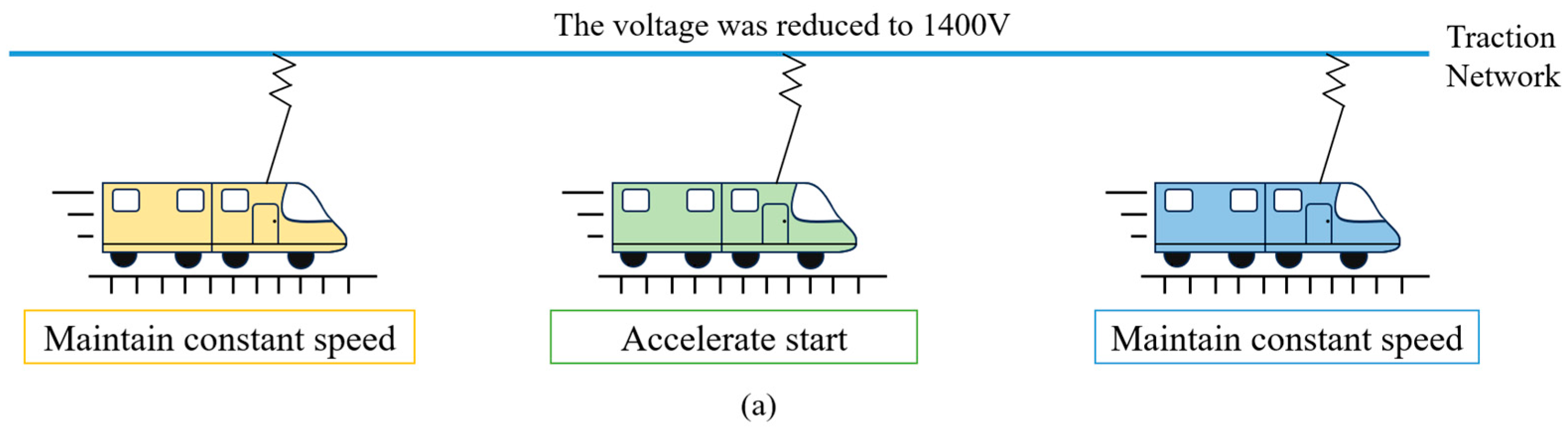

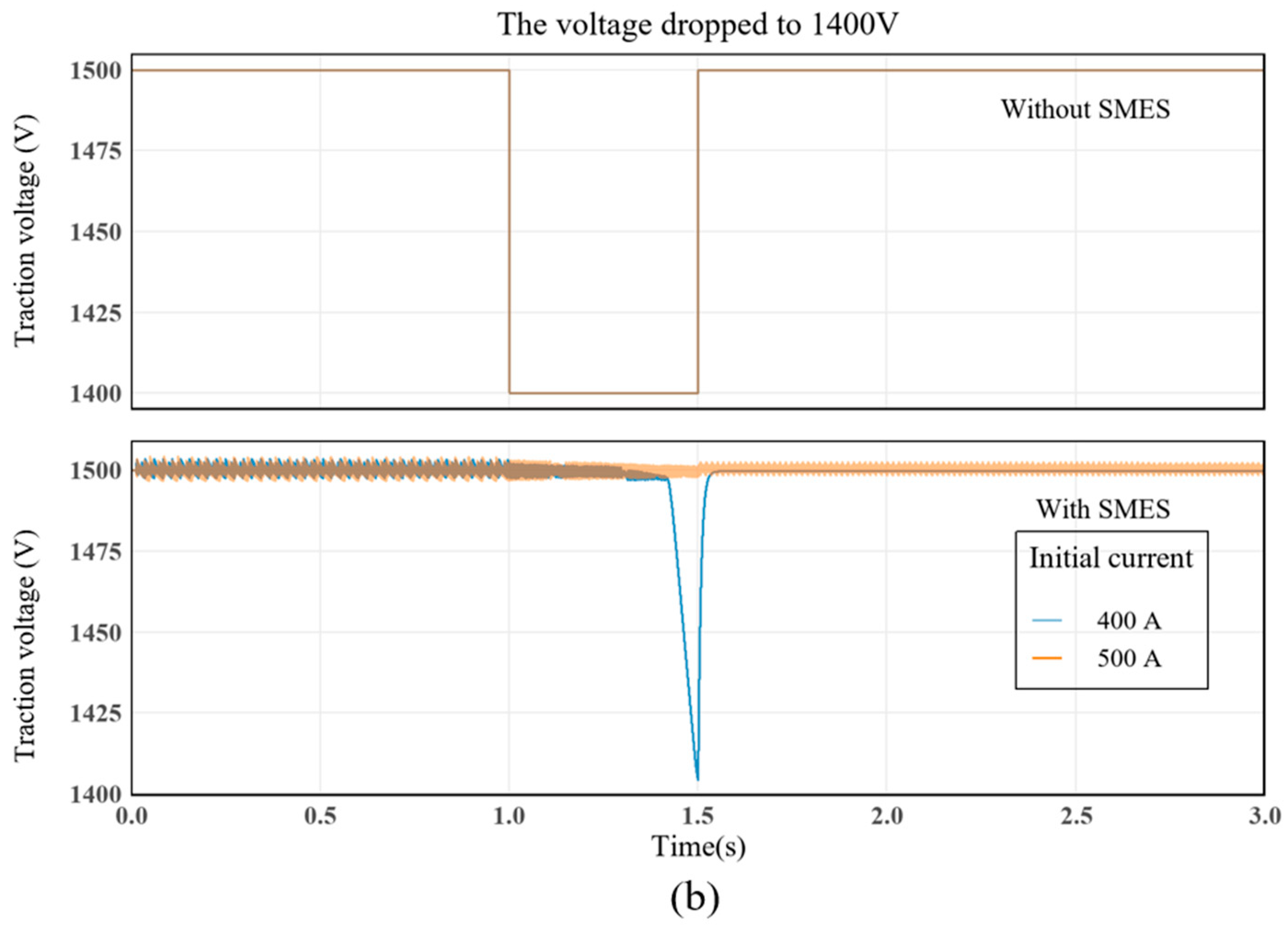

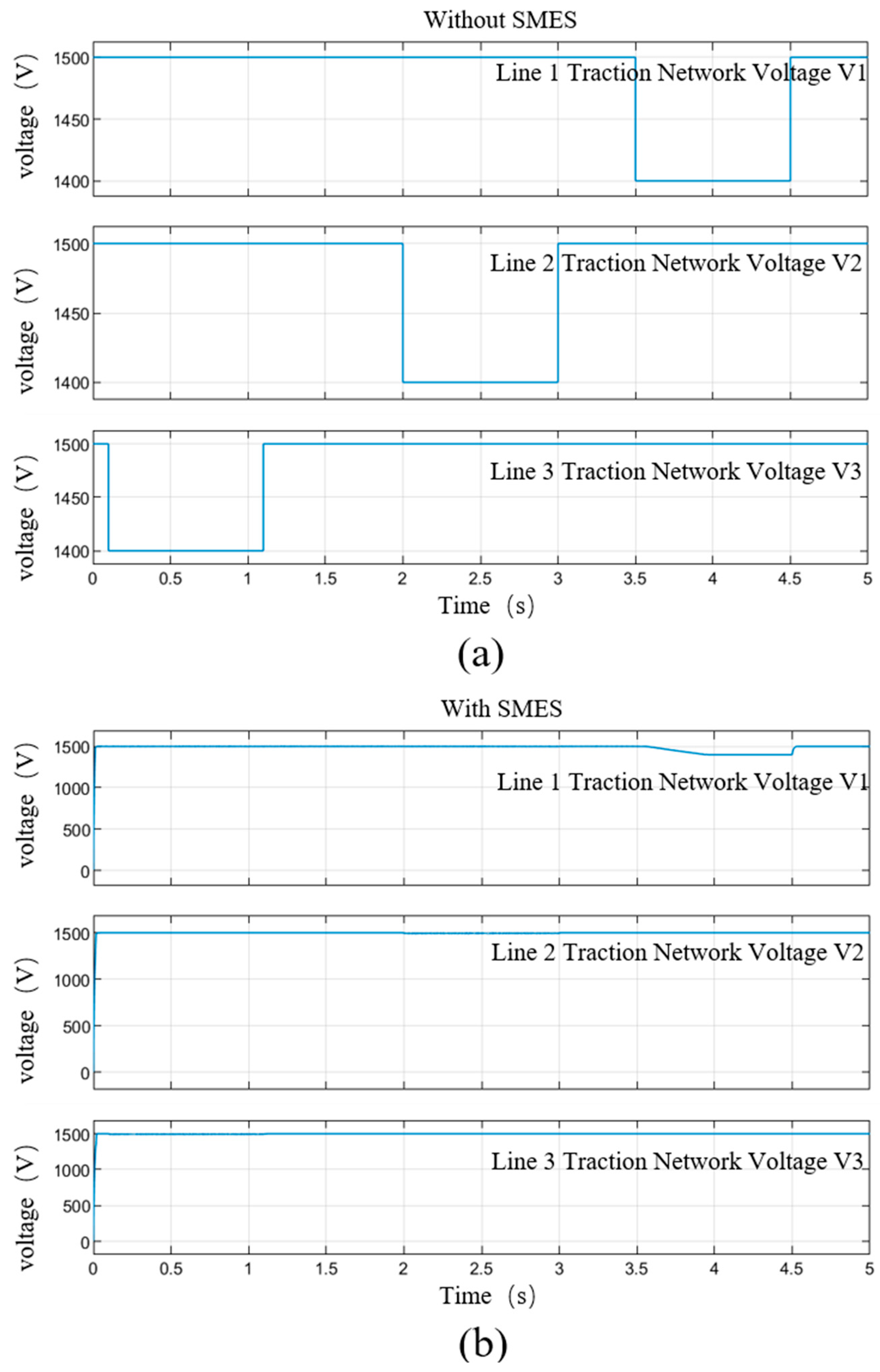

- Simulation Results for Traction system Voltage Decrease

4.2.2. Analysis

4.3. Multi-Line Study

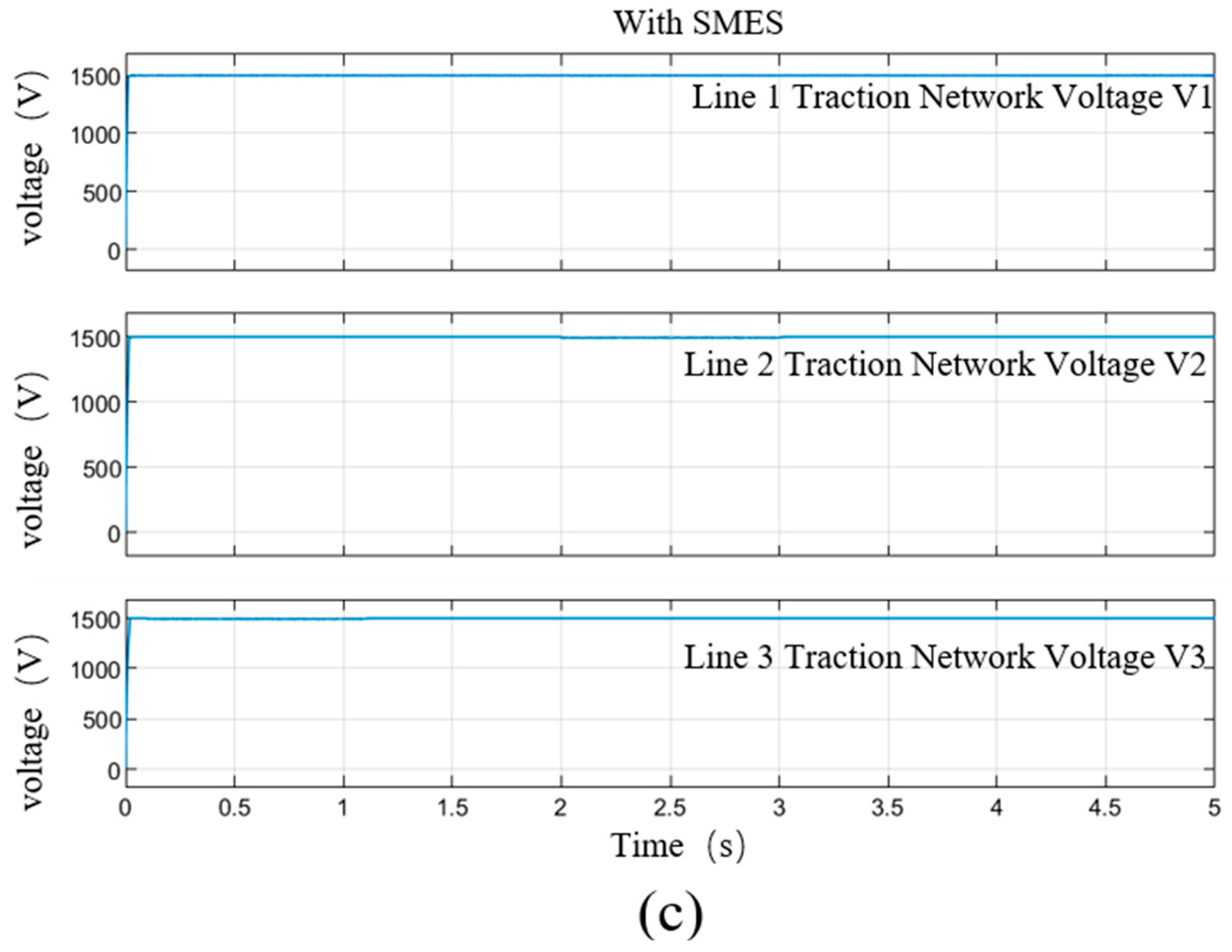

4.3.1. Different Scenarios of Multi-Line Operation

4.3.2. Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bi, Z.; Guo, R.; Khan, R. Renewable Adoption, Energy Reliance, and CO2 Emissions: A Comparison of Developed and Developing Economies. Energies 2024, 17, 3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, J.; Castro, R. Green Hydrogen Energy Systems: A Review on Their Contribution to a Renewable Energy System. Energies 2024, 17, 3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adetokun, B.B.; Oghorada, O.; Abubakar, S.J. Superconducting magnetic energy storage systems: Prospects and challenges for renewable energy applications. J. Energy Storage 2022, 55, 105663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsénio Costa, A.J.; Morais, H. Power Quality Control Using Superconducting Magnetic Energy Storage in Power Systems with High Penetration of Renewables: A Review of Systems and Applications. Energies 2024, 17, 6028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Fu, L.; Chen, X.; Jiang, S.; Chen, X.; Xu, J.; Shen, B. Ultra-low electrical loss superconducting cables for railway transportation: Technical, economic, and environmental analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 445, 141310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Chau, K.T.; Liu, C.; Gao, S.; Li, F. Transient stability analysis of SMES for smart grid with vehicle-to-grid operation. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2011, 22, 5701105. [Google Scholar]

- Alkhafaji, A.S.; Trabelsi, H. Uses of Superconducting Magnetic Energy Storage Systems in Microgrids under Unbalanced Inductive Loads and Partial Shading Conditions. Energies 2022, 15, 8597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Hong, Y.; Lan, J.; Yang, Y. Multi-Functional Device Based on Superconducting Magnetic Energy Storage. Energies 2024, 17, 3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boom, R.W.; Peterson, H.A. Superconductive energy storage for power systems. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1972, 8, 701–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boenig, H.J.; Hauer, J.F. Commissioning tests of the Bonneville power administration 30 MJ superconducting magnetic energy storage unit. IEEE Power Eng. Rev. 1985, 104, 302–312. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S. Research on the Ring-Shaped High-Temperature Superconducting Energy Storage Magnet’s State Assessment Method. Ph.D. Thesis, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Qiu, Q.; Zhang, G.; Lin, L.; Xiao, L. Current research status and application prospect of SMES. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2016, 34, 68–80. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y. Structural Design and Research on Thermal Stability of 10 MJ HTS SMES. Master’s Thesis, North China Electric Power University, Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ishigaki, Y.; Shirahama, H.; Kuroda, K. Power control experiments using a 5 MJ superconducting magnetic energy storage system. In Proceedings of the PESC’88 Record, 19th Annual IEEE Power Electronics Specialists Conference, Kyoto, Japan, 11–14 April 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Honma, H.; Fujibayashi, K.; Asano, K.; Endo, M. Development of a 1 MJ SMES with quench enthalpy protection. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 1993, 83, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Seong, K.C.; Cho, J.W.; Bae, J.H.; Sim, K.D.; Kim, S. 3 MJ/750 kVA SMES System for Improving Power Quality. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2006, 16, 574–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Wen, J.; Wang, S.; Shi, J.; Ren, L.; Tang, Y.; Peng, X. Development and test of moveable conduction-cooled high-temperature superconducting magnetic energy storage system. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2011, 31, 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Song, M.; Shi, J.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Hu, N.; Tang, Y.; Ren, L.; Li, J. 100 kJ/50 kW HTS SMES for Micro-Grid. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2015, 25, 5700506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Baba, J.; Shutoh, K.; Masada, E. Effective application of superconducting magnetic energy storage (SMES) to load leveling for high speed transportation system. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2004, 14, 713–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Wang, B.; Ma, T. Superconducting magnetic energy storage system: Status and prospect. Electr. Power Constr. 2016, 37, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Song, M.; Zou, X.; Ma, T.; Li, L.; Long, F.; Xu, Y. Overall design of a 5 MW/10 MJ hybrid high-temperature superconducting energy storage magnets cooled by liquid hydrogen. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2024, 37, 025003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Fu, L.; Jiang, S.; Shen, B. Superconducting hydrogen-electricity multi-energy system for transportation hubs: Modeling, technical study and economic-environmental assessment. Appl. Energy 2025, 401, 126823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xie, Q.; Bian, X.; Shen, B. Energy-saving Superconducting Magnetic Energy Storage (SMES) Based Interline DC Dynamic Voltage Restorer. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 8, 238–248. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H.; Tian, Z.; Spencer, J.; Fletcher, D.; Hajiabady, S. Coordinated control strategy of railway multisource traction system with energy storage and renewable energy. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 15702–15713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceraolo, M.; Lutzemberger, G.; Meli, E.; Pugi, L.; Rindi, A.; Pancari, G. Energy storage systems to exploit regenerative braking in DC railway systems: Different approaches to improve efficiency of modern high-speed trains. J. Energy Storage 2018, 16, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, Y. The Strategy of Multiphase Interleaved Bi-Directional DC-DC Converter for Absorbing the Regenerating Energy in Metro-Transit Systems. Master’s Thesis, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z. Analysis of the Impact of Voltage Fluctuations on Subway Equipment from the State Grid Side and Countermeasures. Mech. Electr. Inf. 2025, 9, 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, S. On the solution to the problem of anti-voltage fluctuation of subway elevator power supply. Autom. Appl. 2021, 4, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, N.; Ge, Y. Energy storage placements for renewable energy fluctuations: A practical study. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2022, 38, 4916–4927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Kong, H.; Ma, J.; Jia, L. Overview of resilient traction power supply systems in railways with interconnected microgrid. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 7, 1122–1132. [Google Scholar]

- Bade, S.K.; Kulkarni, V.A. Analysis of Railway Traction Power System Using Renewable Energy: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Computation of Power, Energy, Information and Communication (ICCPEIC), Chennai, India, 28–29 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, M.; Chen, X.; Shen, B. Multifunctional superconducting magnetic energy compensation for the traction power system of high-speed maglevs. Electronics 2024, 13, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, W.; Lin, G.; Chen, X.; Fu, L. Superconducting Magnetic Energy Storage (SMES) for Urban Railway Transportation. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2024, 34, 5701304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J. Study on Energy Consumption Analysis and Energy Saving Forecast of Ventilation and Air Conditioning System in Subway Station. Master’s Thesis, Hebei University of Architecture, Zhangjiakou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xun, J.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Y. Pattern recognition of electrical energy for urban rail transit by using data mining. J. Beijing Jiaotong Univ. 2020, 44, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, Y. Research on Power Lighting Systems for Subway Stations. Sci. Technol. Innov. Inf. 2018, 1, 82–83. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R. Research on Regenerating Energy Utilization Technique in Urban Rail System. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, S.; Gou, H.; Zhou, P.; Yang, R.; Shen, B. Energy reliability enhancement of a data center/wind hybrid DC network using super-conducting magnetic energy storage. Energy 2023, 263, 125622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 1402-2010; Railway Applications. Supply Voltages of Traction Systems. State General Administration of the People’s Republic of China for Quality Supervision and Inspection and Quaran-tine: Beijing, China; National Standardization Administration: Beijing, China, 2011.

- Wu, D. Research on Photovoltaic Grid-Connected Low-Voltage Ride-Through Based on Superconducting Magnetic Energy Storage. Master’s Thesis, Hunan University, Changsha, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Item | Parameters | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Traction system | DC voltage | 1500 V |

| Current | 1000 A | |

| Power | 1500 KW | |

| SMES | Inductance | 1 H |

| Operating current | 500 A | |

| Energy storage | 125 KJ |

| Item | 500 A | 600 A |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum voltage fluctuation (Line 1) | 6.667% | 0.267% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mo, W.; Shen, B.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Fu, L. Study on Superconducting Magnetic Energy Storage for Large Subway Stations with Multiple Lines. Energies 2025, 18, 5596. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215596

Mo W, Shen B, Chen X, Chen Y, Fu L. Study on Superconducting Magnetic Energy Storage for Large Subway Stations with Multiple Lines. Energies. 2025; 18(21):5596. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215596

Chicago/Turabian StyleMo, Wenjing, Boyang Shen, Xiaoyuan Chen, Yu Chen, and Lin Fu. 2025. "Study on Superconducting Magnetic Energy Storage for Large Subway Stations with Multiple Lines" Energies 18, no. 21: 5596. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215596

APA StyleMo, W., Shen, B., Chen, X., Chen, Y., & Fu, L. (2025). Study on Superconducting Magnetic Energy Storage for Large Subway Stations with Multiple Lines. Energies, 18(21), 5596. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215596