Application of Management Controlling in the Energy and Heating Sector: Diagnosis of Implementation Level and Identification of Development Barriers in the Context of Other Economic Sectors

Abstract

1. Introduction

- −

- RQ 1a: which internal conditions and organisational factors contributed to the unsuccessful implementation of management controlling in the examined energy and heating enterprise, despite formal completion of project assumptions and acceptance of proposed changes?

- −

- RQ 1b: is there a noticeable trend in the surveyed E&H companies that the size of the company (measured by size classes) is related to the scope of management controlling?

- −

- RQ 1c: what are the observed differences in the application of management controlling between the surveyed E&H companies, taking into account their ownership status (public and private companies)?

- −

- RQ 1d: are there any visible links between the type of activity (manufacturing/trade/services) and the scale of operations (e.g., large vs. smaller entities) or the level of maturity and the scope of management controlling in the surveyed E&H companies?

- −

- RQ 1e: is there a noticeable tendency in the surveyed E&H companies that the length of the company’s operation (measured by the length of time it has been on the market) is related to the scope of management controlling?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Overview of Research in the Field of Controlling Implementation

2.2. Implementation of Controlling in Companies in the Energy and Heating Sector

3. Case Study—The Process of Implementing Controlling in an Energy Company

3.1. Description of the Research Entity

- −

- The production and supply of steam, hot water, and air for air conditioning systems; the transmission and distribution of heat; and heat trading,

- −

- Construction work related to the erection of residential and non-residential buildings,

- −

- The installation of water supply and sewerage systems.

3.2. Characteristics of the Implementation Project

- −

- Overly complex cost accounting rules, although reflecting the complexity of the business processes carried out,

- −

- Complicated and unclear accounting code rules, which are difficult to process further, have been modified many times and are inconsistent with the existing organisational structure,

- −

- Lack of an attribute database for accounting account segments, which significantly limited reporting capabilities, analysis and drilling down of data in cross-sections useful for management information,

- −

- Omission of profit centres,

- −

- Lack of a generic cost account, unformulated rules for the management grouping of generic accounts,

- −

- No management model for presenting financial results or margin/financial coverage accounts, resulting in a lack of comprehensive or cascading logic for presenting management information,

- −

- Lack of comments on results and deviations from budgets, which could provide information to a wider group of managers,

- −

- Limited use within the organisation of information prepared by the controlling department, lack of involvement of managers in the analysis and explanation of deviations from the budget,

- −

- No link between the remuneration systems for managers and the achievement of financial objectives or tasks resulting from the budget or the strategy management system,

- −

- Fragmented system of data supply from various incompatible systems: F-K programme, Ms Excel, investment record system, without the possibility of referring to source data and/or the need to make individual corrections to individual data,

- −

- An overly complicated and labour-intensive reporting system,

- −

- An overly complex planning system based on extensive procedures, which does not bring any added value, is centrally managed and does not take into account the needs of smaller organisational units,

- −

- Lack of forecasting and financial planning procedures, with reporting and management limited to a single, unchanging annual financial plan.

3.3. Results Achieved

3.4. Summary of Project Results

3.5. Evaluation of the Project and Conclusions

- −

- Limited involvement in the project and its implementation on the part of senior management, changes in the composition of the management board, and the departure of the board member who initiated the project, resulting in a lack of further determination to implement it,

- −

- Strongly articulated dissatisfaction of the controlling department, which had to adapt to a new model of management reporting and new tasks,

- −

- An organisational culture characterised by resistance to change and limited awareness of the impact on the overall operations and functioning of the company.

- −

- The company’s deep roots in a complex network of regulations, rules and public management, which fundamentally hindered and limited agile management. In addition, the company’s extensive hierarchical organisational structure and highly formalised management culture also hampered the continuation of the project.

- −

- Lack of integration of the project with the company’s development strategy.

4. Empirical Framework

4.1. Data and Descriptive Statistics

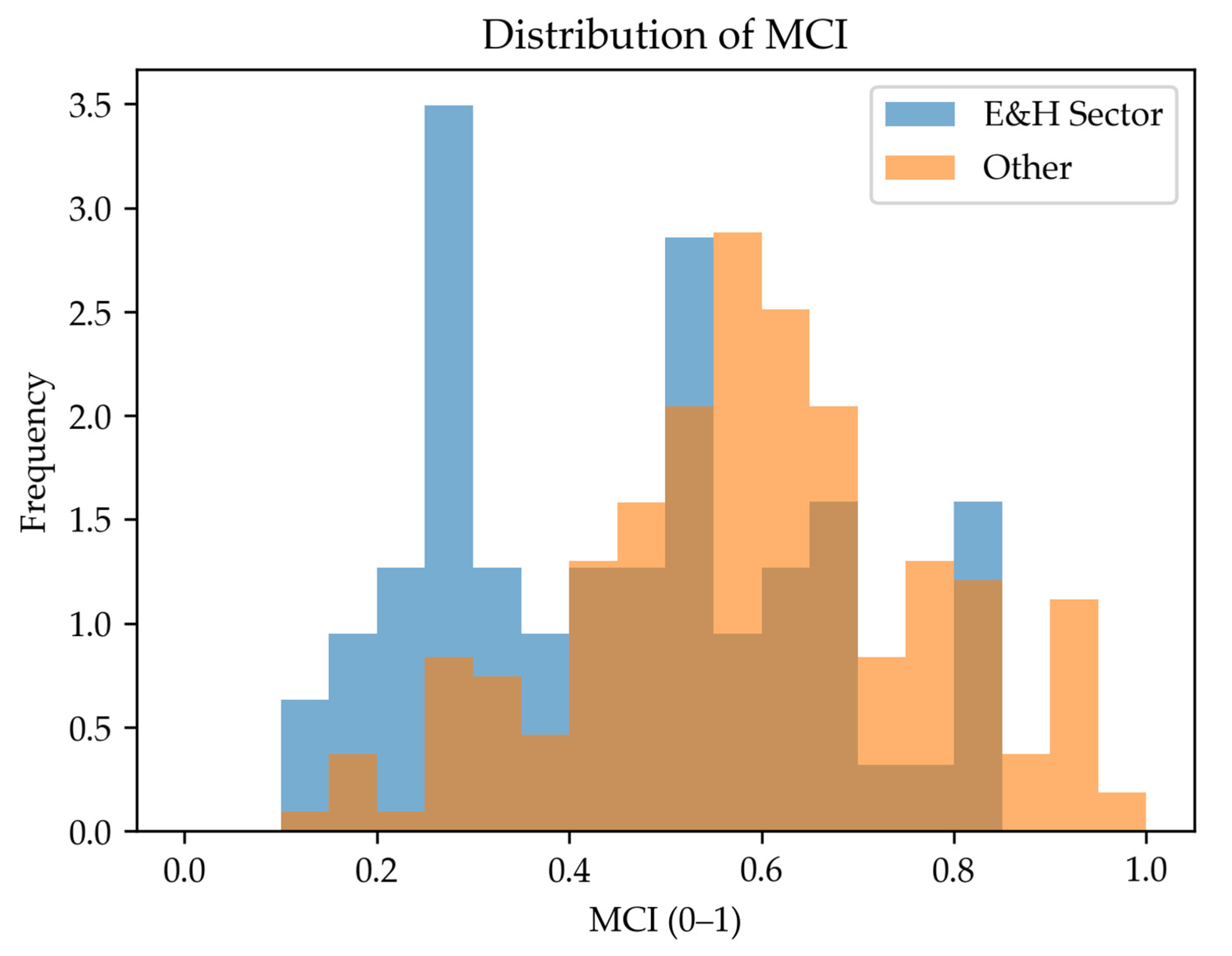

Managerial Controlling Index (MCI)

4.2. Differences Within the Sector in MCI Between E&H Firms

4.3. Item-Level Contrasts Between Management Controlling Components

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- −

- Uniformity of practices in the E&H sector. Management controlling practices are relatively homogeneous, regardless of the size, age, or business profile of the company. This may indicate the existence of a common organisational model that does not favour differentiation in the level of management maturity.

- −

- Marginal impact of ownership form. Public companies show a slightly higher level of management controlling maturity than private companies, which may result from a greater emphasis on process formalisation and compliance with regulations. However, these differences are minor and do not determine the quality of the controlling.

- −

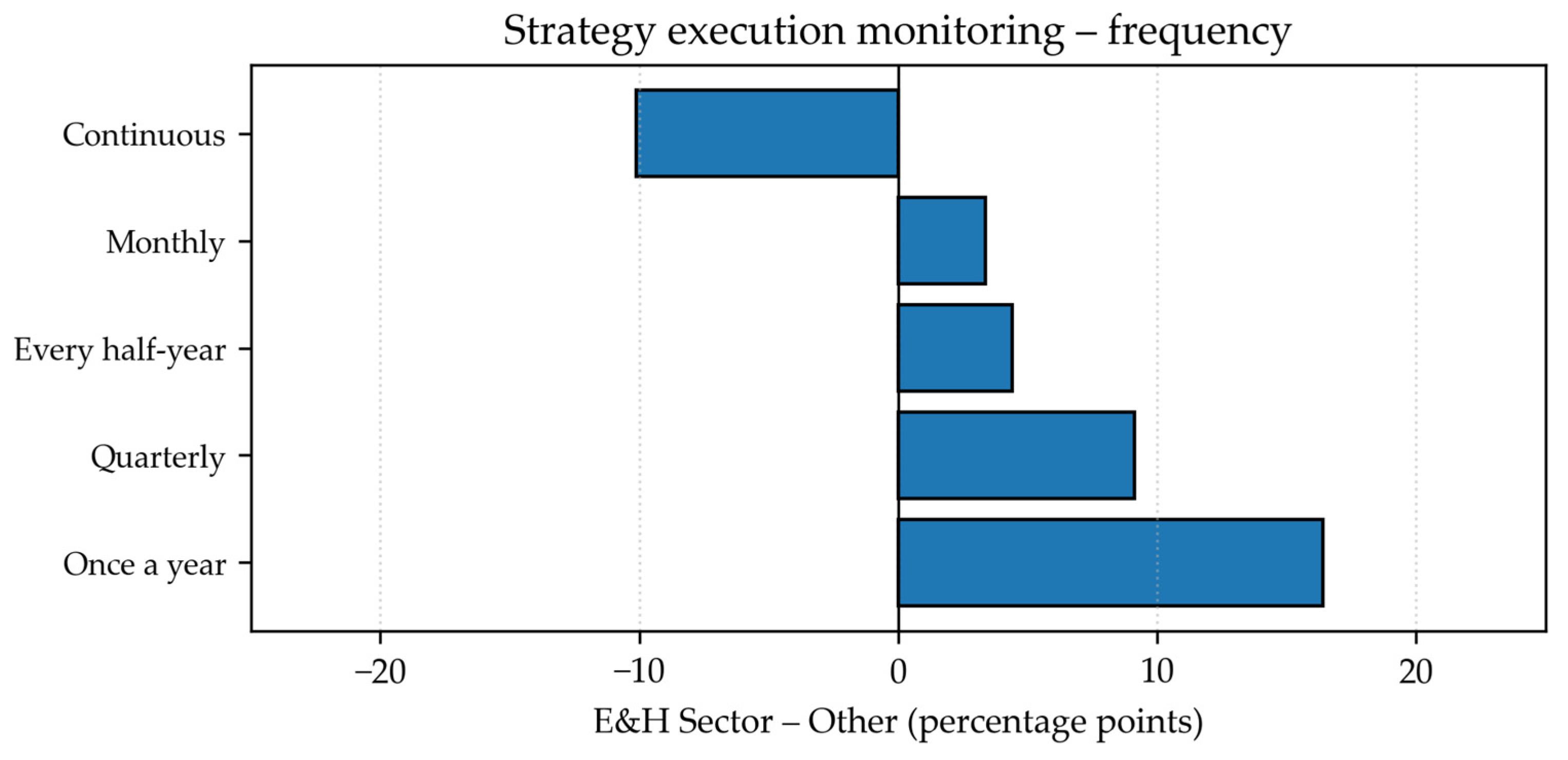

- Deficits in strategy monitoring and ownership. Strategy monitoring is mainly carried out on an annual basis, and the responsibility for its implementation rarely rests with line managers. This limits the operational anchoring of strategic objectives and hinders their effective implementation.

- −

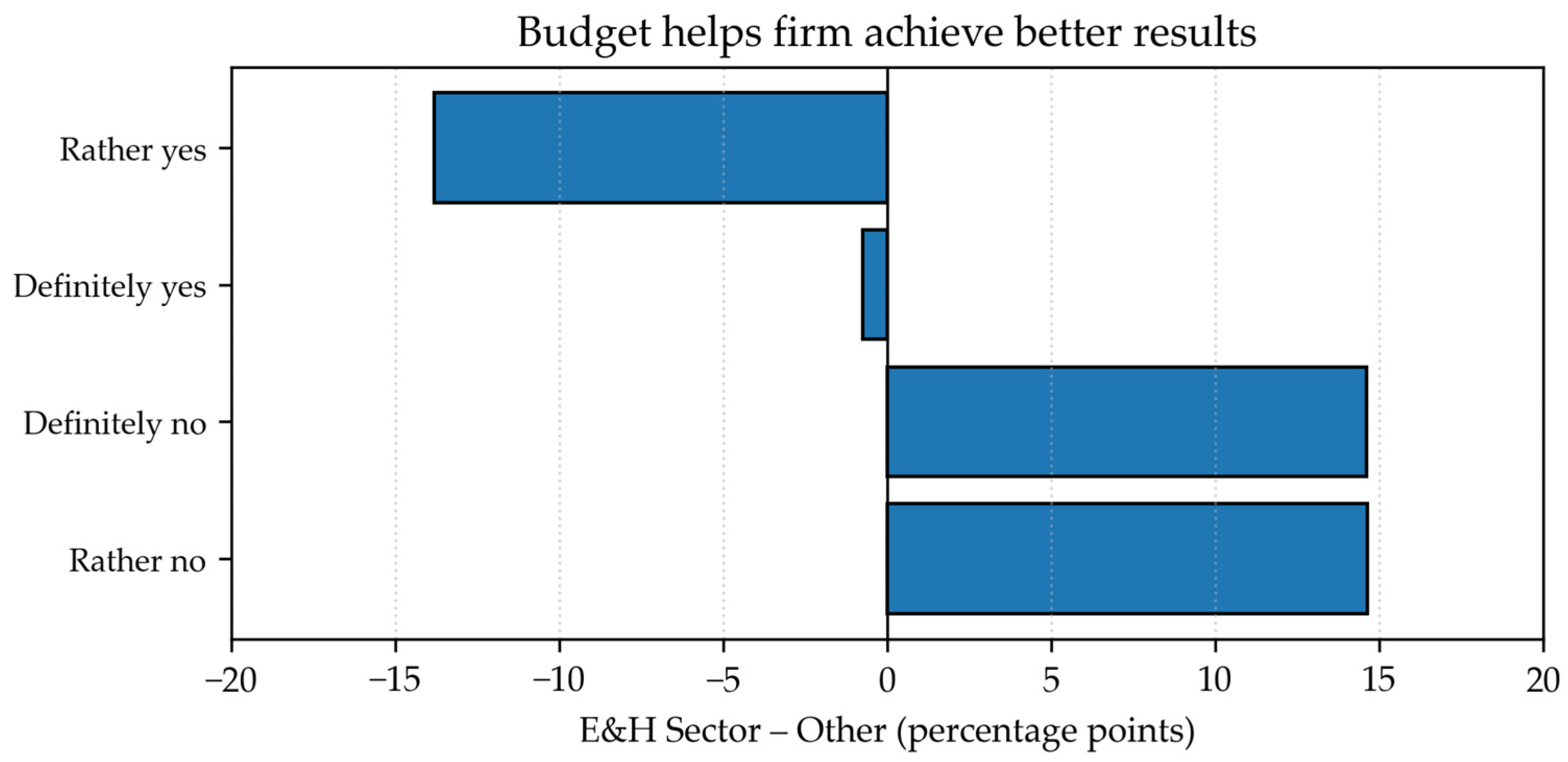

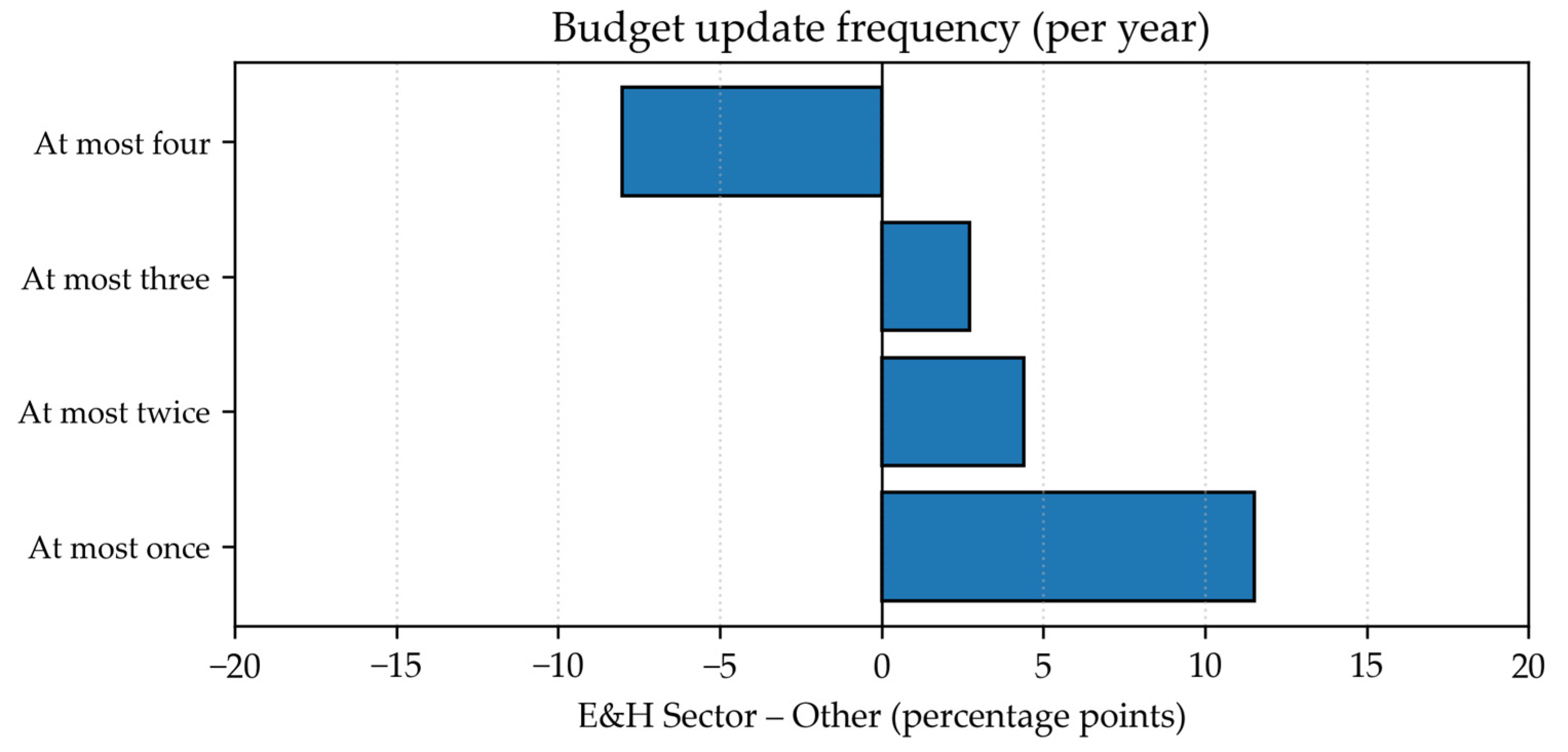

- Low budget flexibility. Rare budget updates during the year and limited belief in its impact on results indicate a static approach to planning, which may be insufficient in a volatile environment.

- −

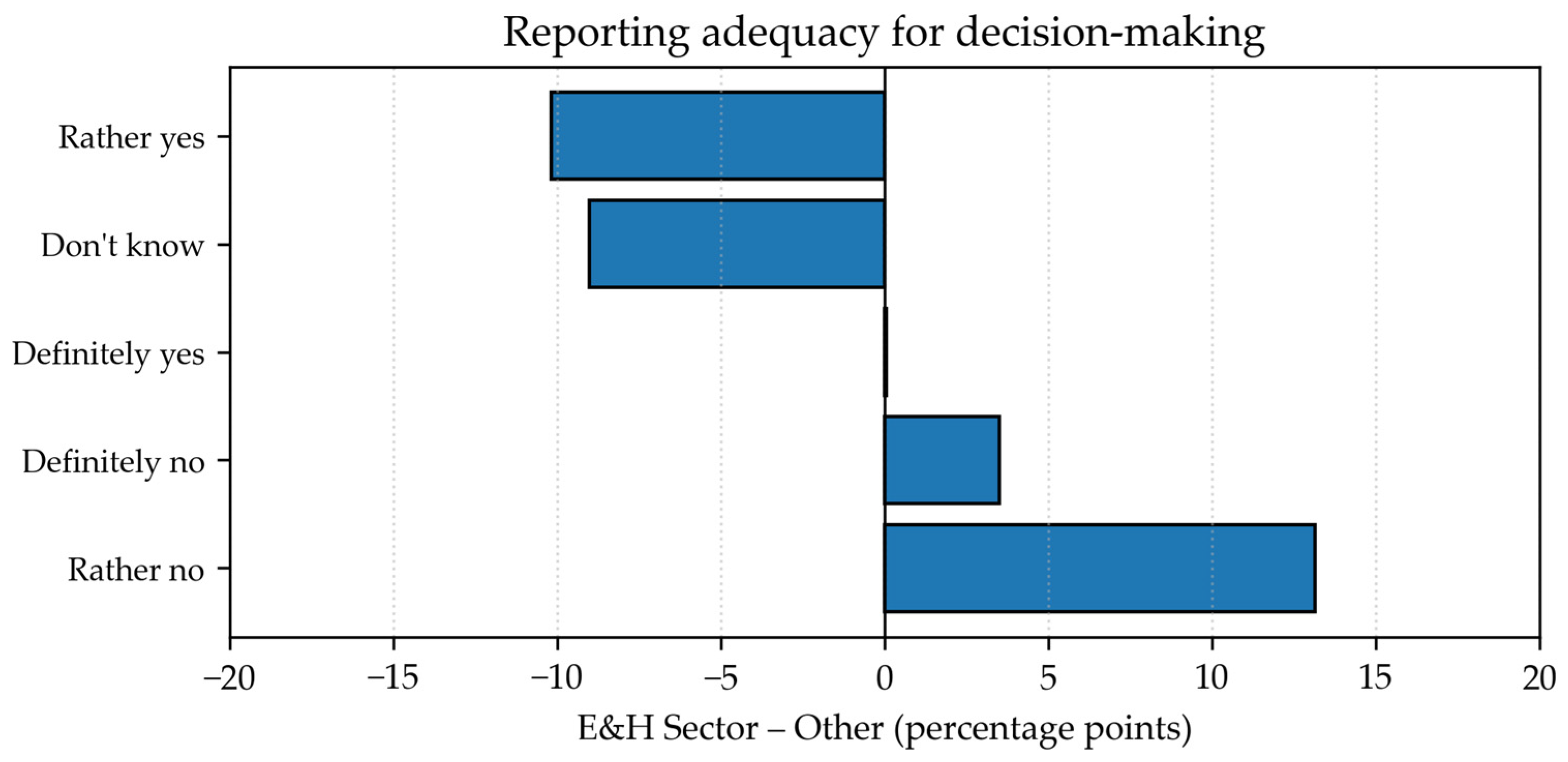

- Insufficient reporting for decision-making purposes. Controlling reports are often considered insufficient for management decision-making, which limits their value as a tool supporting effective management.

- −

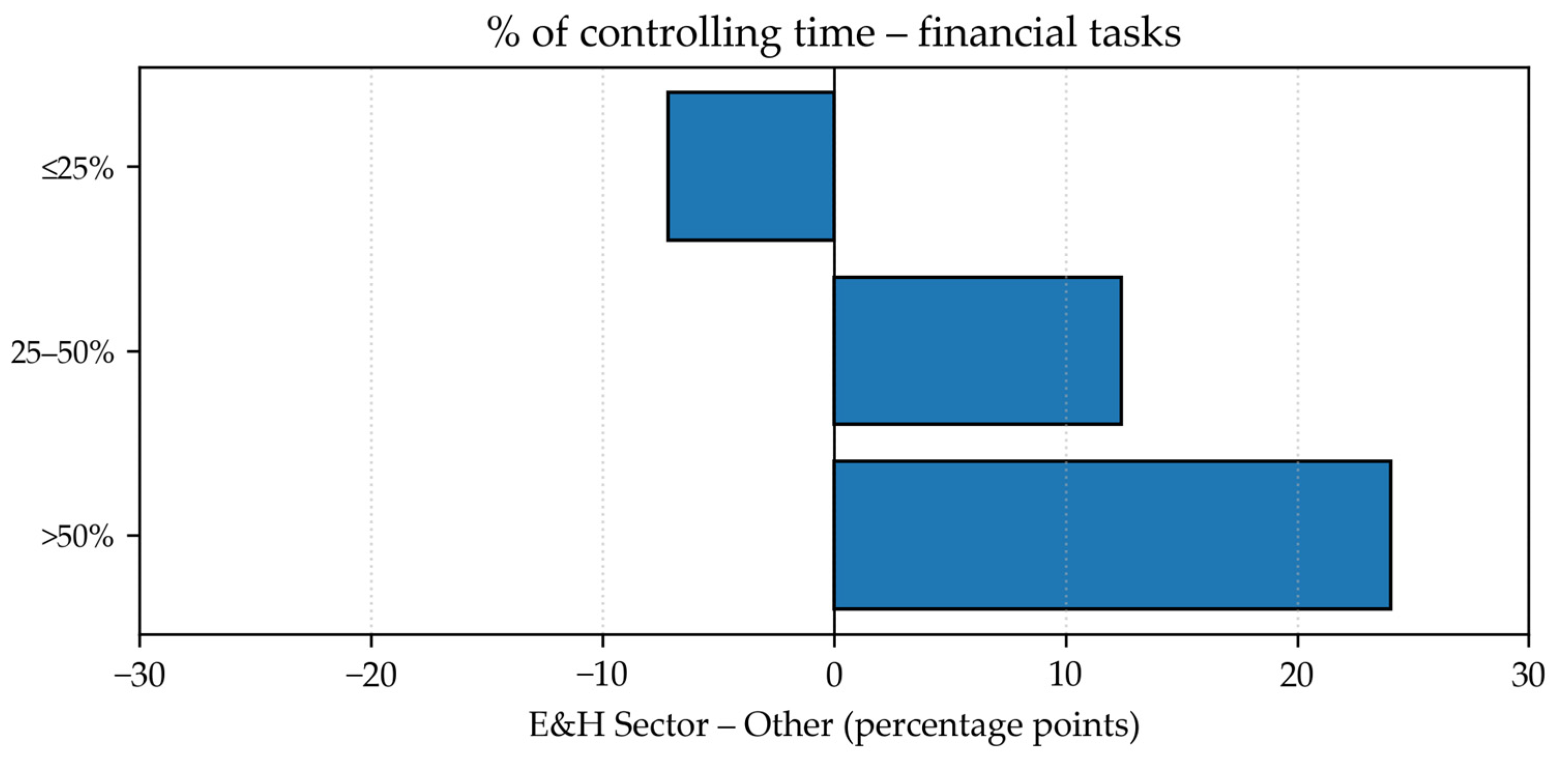

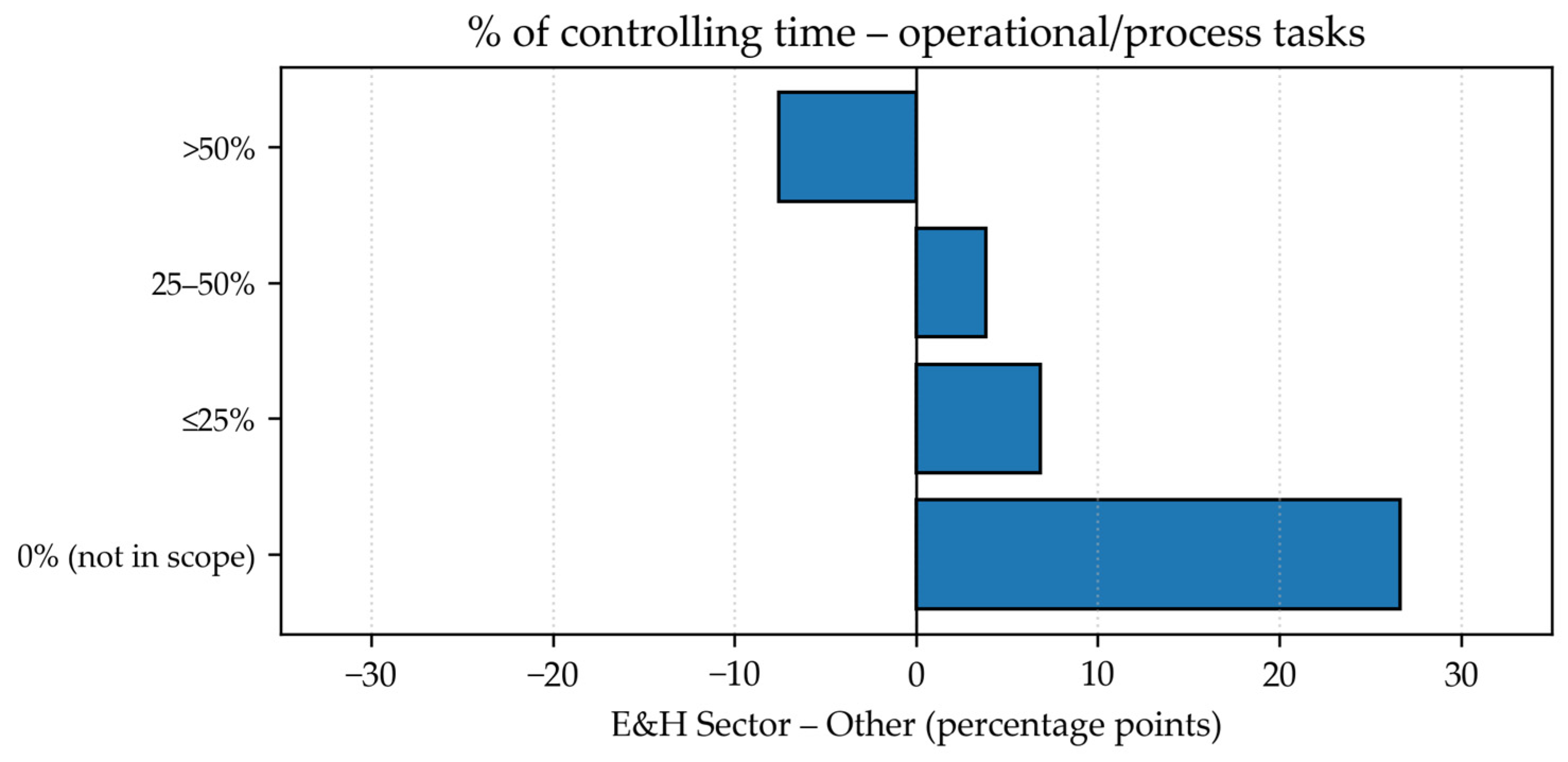

- Focus on controlling financial tasks. Controlling departments in the E&H sector focus mainly on financial tasks, with limited involvement in process optimisation and operational decision support.

- −

- Strengthening the management controlling function. The expansion of the controller’s role from a reporting function to active decision-making and strategic support, as well as the integration of controlling with the processes of planning, monitoring, and evaluating the achievement of objectives.

- −

- Increase the frequency of strategy monitoring. Implement quarterly or continuous reviews of the implementation of the strategy and link the monitoring to the KPI system and the budget cycle.

- −

- Decentralise the responsibility for strategy monitoring. Involve line managers in the process of monitoring and reporting on the achievement of objectives and strengthen cooperation between the controlling department and operational units.

- −

- Modernisation of the budgeting process. Increasing the flexibility and frequency of budget updates (e.g., rolling forecasts) and linking them to measurable strategic and operational objectives.

- −

- Improving the quality of management reports. Systematic review and optimisation of the structure of the report in terms of its usefulness for decision-making and the implementation of Business Intelligence (BI) tools enabling interactive data analysis.

- −

- Balancing the allocation of the controlling department’s working time. Reducing excessive focus on financial tasks in favour of operational and process activities, including performance analysis, innovation support, and operational optimisation.

- −

- Development of management controlling competencies. Training for controllers and managers in strategic controlling, data analysis and communication, and promotion of a culture of cooperation and knowledge sharing.

- −

- Benchmarking and exchange of good practices. Comparison of your own practices with companies outside the E&H sector that achieve higher MCI values and participation in industry initiatives, conferences, and development projects.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baldi, N. Management of innovations in public governance: Quality management system, management controlling and internal auditing appropriation. Mark. Manag. Innov. 2020, 2, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijethilake, C.; Munir, R.; Appuhami, R. Environmental innovation strategy and organisational performance: Enabling and controlling uses of management control systems. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 1139–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matusiak, B.E. Modele Biznesowe Na Zintegrowanym Rynku Energii; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Polska, 2014; ISBN 978-83-7969-151-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weron, A.; Weron, R. Giełda Energii: Strategie Zarządzania Ryzykiem; CIRE: Wrocław, Polska, 2000; ISBN 8391386406. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, R.N.; Govindarajan, V. Management Control System, 12th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0073100890. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. The Strategy Focused Organisation: How Balanced Scorecard Companies Thrive in the New Business Environment; Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; ISBN 1-57851-250-6. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, R. Levers of Control; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, A.; Otley, D. The design and use of performance management systems: An extended framework for analysis. Manag. Account. Res. 2009, 20, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, E. (Ed.) Controlling W Działalności Przedsiębiorstwa; PWE: Warszawa, Polska, 2010; ISBN 9788320819090. [Google Scholar]

- Horváth, P.; Gleich, R.; Seiter, M. Controlling; Vahlen: München, Germany, 2015; ISBN 978-3800649549. [Google Scholar]

- Zangemeister, A. Entwicklungsorientiertes Controlling im Total Quality Management. Konzeption und Instrumentelle Umsetzung; Springer Fachmedien: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1999; ISBN 978-3-8244-6994-9. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, W.; Ulrich, P. Handbuch Controlling; SpringerGabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2022; ISBN 978-3658264307. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, J.; Schäffer, U. Introduction to Controlling; Schäffer-Poeschel: Stuttgard, Germany, 2008; ISBN 978-3791027593. [Google Scholar]

- Nesterak, J. Controlling Zarządczy; Wolters Kluwer: Warszawa, Polska, 2015; ISBN 978-83-264-8536-7. [Google Scholar]

- Schallmo, D.R.A.; Rusnjak, A.; Anzengruber, J.; Werani, T.; Lang, K. Digitale Transformation von Geschäftsmodellen. Grundlagen, Instrumente und Best Practices; SpringerGabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2021; ISBN 978-3-658-12387-1. [Google Scholar]

- Schäffer, U.; Weber, J. Die Digitalisierung wird das Controlling radikal verändern. Control. Manag. Rev. 2016, 60, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedl, G. Künstliche Intelligenz im Controlling. Controlling 2019, 31, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langman, C.H. Digitalisierung im Controlling; SpringerGabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3658250164. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtarski, J.M.; Nowosielski, K. Metodyka pomiaru stanu zaawansowania controllingu w małych i średnich przedsiębiorstwach. In Prace Naukowe Akademii Ekonomicznej we Wrocławiu; Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej im. Oskara Langego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2006; Volume 1101, pp. 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Łapińska, A.; Dynowska, J. Zakres zadań i oznaczenia stanowiska controllera w przedsiębiorstwie w świetle badań ankietowych. In Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu; Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej im. Oskara Langego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2010; Volume 123, pp. 318–327. [Google Scholar]

- Reichman, T. Controlling: Concepts of Management Control, Controllership and Ratios; Springer: Dortmund, Germany, 1997; ISBN 978-3-642-64546-4. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, J.; Schäffer, U. Is ensuring management rationality a controlling task? In Behavioral Controlling; Schäffer, U., Ed.; Springer Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesterak, J. Bariery procesu wdrażania controllingu w przedsiębiorstwach działających w Polsce w świetle prowadzonych badań. Misc. Oeconomicae 2014, 1, 237–248. [Google Scholar]

- Dynowska, J. Czynniki ograniczające wdrażanie controllingu w świetle badań ankietowych. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2015, 399, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jánská, M.; Celer, Č.; Žambochová, M. Application of corporate controlling in the Czech Republic. Sci. Pap. Univ. Pardubic. Ser. D 2017, 40, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Mykhaylychenko, N.; Tokarev, A.; Pro Mykhaylychenko, N.; Tokareva, A. Problems and prospects of implementation controlling as a modern enterprise management tool. Экoнoмический вестник Дoнбасса 2016, 4, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Gleich, R. Data Driven Controlling. Data Analytics und KI Kennen und Nutzen; Haufe Lexware GmbH: Schäffer-Poeschel, Germany, 2023; ISBN 978-3648173879. [Google Scholar]

- Mihăilăa, M. Managerial accounting and decision making, in energy industry. Procedia—Social. Behav. Sci. 2014, 109, 1199–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kes, Z.; Kubalańca, L. Controlling w zakładach energetycznych. In Prace Naukowe Akademii Ekonomicznej we Wrocławiu; Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej im. Oskara Langego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2001; Volume 902, pp. 212–218. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Tworek, K.; Bieńkowska, A.; Zabłocka-Kluczka, A. Coexistence of business continuity management and controlling: Controlling use as a moderator of relation between BCM maturity and organisational results. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2019, 10, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stochastic Model Predictive Control, Energy Efficient Building Control, Smart Grid. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/article/id/188555-predictive-models-aid-energy-efficient-management/pl (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Kapustka, K. System wskaźników KPI jako fundament systemu controllingu dokonań w elektroenergetyce. In Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu; Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej im. Oskara Langego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2010; Volume 122, pp. 204–212. [Google Scholar]

- Bek-Gaik, B.; Surowiec, A. Controlling finansowy w przedsiębiorstwie energetycznym. In Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu; Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej im. Oskara Langego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2011; Volume 181, pp. 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Borowiec, L. Zbilansowana karta dokonań jako instrument controllingu w przedsiębiorstwie energetyki cieplnej. Rynek Energii 2011, 5, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Soni, V.; Dash, A.P.; Singh, S.P.; Banwet, D.K. Life Cycle Costing Analysis of Energy Options: In Search of Better Decisions towards Sustainability in Indian Power &Energy Sector. Glob. J. Manag. Bus. Res. 2014, 14, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalewski, M. Umiejscowienie controllingu oraz zasady wyodrębniania ośrodków odpowiedzialności za koszty w Miejskim Przedsiębiorstwie Energetyki Cieplnej. Finanse. Rynk. Finans. Ubezpieczenia 2017, 4, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topor, D.I.; Căpușneanu, S.; Constantin, D.M.; Barbu, C.M.; Rakos, I.S. ABB-ABC-ABE-ABM Approach for Implementation in the Economic Entities from Energy Industry. Bus. Manag. Horiz. 2017, 5, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Möller, K.; Schäffer, U. Digitalization in management accounting and control: An editorial. J. Manag. Control. 2020, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesterak, J.; Kołodziej-Hajdo, M.; Kowalski, M. Controlling in the Process of Development of the Energy and Heating Sector Based on Research of Enterprises Operating in Poland. Energies 2023, 16, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubik, J. Ewolucja controllingu w Energetyce Kaliskiej S.A. In Prace Naukowe Akademii Ekonomicznej we Wrocławiu; Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej im. Oskara Langego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2005; Volume 1080, pp. 366–374. [Google Scholar]

- Konsek-Ciechońska, J. Operational and strategic controlling tools in microenterprises—Case study. Manag. Syst. Prod. Eng. 2017, 25, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubik, J. Model Controllingu kosztów i jego Zastosowanie w Zakładach Energetycznych; Wydawnictwo AGH: Kraków, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Szyszłowski, R. Wykorzystanie narzędzi rachunkowości zarządczej w przedsiębiorstwach energetyki cieplnej. Rynek Energii 2004, 4, 52–54. [Google Scholar]

- Mesjasz-Lech, A. Rachunek Kosztów Ekologistyki w Ocenie Proekologicznej Działalności Elektrowni Cieplnych; Wydawnictwo AGH: Kraków, Poland, 2006; pp. 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Rof, L.M.; Farcane, N. Current State and Evolution Perspectives for Management Accounting in the Energy Sector by Implementing the ABC Method; Annals of Faculty of Economics, University of Oradea, Faculty of Economics: Oradea, Romania, 2011; Volume 1, pp. 653–660. Available online: http://anale.steconomiceuoradea.ro/volume/2011/n1/063.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Rof, L.M.; Capusneanu, S. Increase the Performance of Companies in the Energy Sector by Implementing the Activity-Based Costing. Int. J. Acad. Res. Accounting. Financ. Manag. Sci. 2015, 5, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferens, A. Systematyka kosztów środowiskowych w przedsiębiorstwie branży energetycznej do celów decyzyjnych. Zeszyty Teoretyczne Rachunkowości 2016, 86, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadkowski, W. Rachunek Kosztów Jakości jako Narzędzie Efektywnego Zarządzania Kosztami Jakości w Sektorze Energetycznym; Fundacja na rzecz Czystej Energii: Warszawa, Poland, 2018; pp. 305–401. [Google Scholar]

- Szadziewska, A.; Majchrzak, I.; Remlein, M.; Szychta, A. Rachunkowość Zarządcza a Zrównoważony Rozwój Przedsiębiorstwa; Wydawnictwo IUS Publicum: Katowice, Polska, 2021; ISBN 978-83-66922-06-8. [Google Scholar]

- Potkány, M.; Hašková, S.; Lesníková, P.; Schmidtov, J. Perception of the essence of controlling and its use in manufacturing enterprises in times of crisis: Does controlling fulfil its essence? J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2022, 23, 957–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lositska, T.; Bieliaieva, N.; Lagutin, V.; Melnyk, T. Controlling of trade enterprises in the context of the international dimension. Financ. Credit. Act. Probl. Theory Pract. 2022, 1, 92–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Lim, W.M.; Sureka, R.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Bamel, U. Balanced scorecard: Trends, developments, and future directions. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2024, 18, 2397–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haapasalo, H.; Ingalsuo, K.; Lenkkeri, T. Linking strategy into operational management—A survey of BSC implementation in Finnish energy sector. Benchmarking. Int. J. 2006, 13, 701–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stańczyk, I.; Stuss, M.M. Personnel Controlling—Human Capital Management. Results of a Selected Company Listed on the Warsaw Stock Exchange. Int. J. Contemp. Manag. 2018, 17, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesterak, J.; Głodziński, E.; Kowalski, M. Controlling Projektu w Praktyce Przedsiębiorstw Działających w Polsce; Krakowska Szkoła Controllingu: Kraków, Polska, 2018; ISBN 978-83-946066-2-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bousdekis, D.; Mentzas, G. Enterprise Integration and Interoperability for Big Data-Driven Processes in the Frame of Industry 4.0. Front. Big Data 2021, 4, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogundipe, T.; Ewim, S.E.; Sam-Bulya, N.J. Enhancing financial reporting and management efficiency through enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems: A theoretical review for large-scale energy operations. Int. J. Manag. Entrep. Res. 2024, 6, 3415–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardebili, A.A.; Zappatore, M.; Ramadan, A.I.H.A.; Longo, A.; Ficarella, A. Digital Twins of smart energy systems: A systematic literature review on enablers, design, management and computational challenges. Energy Inform. 2024, 7, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dena analysis: Using Artificial Intelligense in the Energy Industry. Available online: https://www.globema.com/dena-analysis-ai-in-energy-sector/ (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Morkisz, P.; Wiącek, M.; Wochlik, I. Wykorzystanie metod obliczeniowych i sztucznej Inteligencji w bezpieczeństwie energetycznym. Wiedza Obronna 2023, 283, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuss, M.M.; Makieła, Z.J.; Herdan, A.; Kuźniarska, G. The Corporate Social Responsibility of Polish Energy Companies. Energies 2021, 14, 3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canova, A.; Profumo, F.; Tartaglia, M. LCC design criteria in electrical plants oriented to energy saving. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2003, 39, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PGE Energia Ciepła, S.A. Raport Zrównoważonego Rozwoju. 2023. Available online: https://pgeenergiaciepla.pl/ (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Bartoszewska, P. Dylematy planowania finansowego w przedsiębiorstwie ciepłowniczym. Nowa Energia 2023, 5–6, 50–52. [Google Scholar]

| Criteria | Management Controlling | Reporting Controlling |

|---|---|---|

| Objective | Support for managerial decision-making and implementation of strategies. | Processing and delivery of information. |

| Scope | Planning, analysis, forecasting, and risk management. | Budgeting, variance analysis, and reporting. |

| Management Level | Strategic, tactical, and operational. | Operational. |

| Technology | BI, AI, machine learning, predictive analytics, interactive dashboards. | ERP, spreadsheets, and reporting systems. |

| Interaction with Managers | Consultations and participation. | Information and instruction. |

| Role of the Controller | Business partner and strategic analyst. | Data expert and report coordinator. |

| Type of Data | Aggregated, scenario-based, and predictive. | Historical, actual, and standard. |

| Type of Organszation | Corporations, project-based organisations, and innovative companies. | Public institutions, SMEs, and hierarchically structured units. |

| Author | Research Objective | Tools/Research Areas |

|---|---|---|

| Kapustka, K. (2010) [32] | Presentation of the KPI system concept as the foundation for performance controlling in the power industry. | KPI indicators: performance, availability, and environmental. |

| Bek-Gaik, B.; Surowiec, A. (2011) [33] | Presentation of the scope of financial controlling in the energy sector in the context of market conditions and regulatory requirements. | Financial ratio analysis, budgeting and variance analysis, BSC. |

| Borowiec, L. (2011) [34] | Study of the applicability of the balanced scorecard (BSC) as a modern controlling tool in district heating companies. | BSC, strategy map, KPIs. |

| Soni, V.; Dash, A.P.; Singh, S.P.; Banwet, D.K. (2014) [35] | Life Cycle Cost (LCC) analysis of different energy generation options in the context of sustainable development in the energy sector. | Life Cycle Costing as a tool of strategic controlling. |

| Kowalewski, M. (2017) [36] | Placement of controlling within the organisational structure of a district heating company and the principles of defining cost responsibility centres. | Cost responsibility centres, Quality Management System (QMS), process mapping and cost classification, and budgeting and cost analysis by departments. |

| Topor, D. I.; Căpușneanu, S.; Constantin, D. M.; Barbu, C. M.; Rakos, I. S. (2017) [37] | Study of the impact of an integrated activity-based approach on decision-making processes and improvement of cost and environmental efficiency in the energy sector. | Integrated controlling approach: ABB (activity-based budgeting), ABC (activity-based costing), ABM (activity-based management), ABE (activity-based emissions). |

| Möller, K.; Schäffer, U. (2020) [38] | Presentation of the impact of digitalisation on the implementation of controlling in enterprises in the E&H sector. | Strategic controlling, financial planning and analysis, reporting, and organisational structures of the enterprise. |

| Nesterak, J.; Kołodziej-Hajdo, M.; Kowalski, M. (2023) [39] | Study of the level of use of basic controlling tools and forms in enterprises in the E&H sector. | Controlling of budgeting and reporting. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kołodziej-Hajdo, M.; Machno, A.; Nesterak, J.; Kowalski, M. Application of Management Controlling in the Energy and Heating Sector: Diagnosis of Implementation Level and Identification of Development Barriers in the Context of Other Economic Sectors. Energies 2025, 18, 4458. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18174458

Kołodziej-Hajdo M, Machno A, Nesterak J, Kowalski M. Application of Management Controlling in the Energy and Heating Sector: Diagnosis of Implementation Level and Identification of Development Barriers in the Context of Other Economic Sectors. Energies. 2025; 18(17):4458. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18174458

Chicago/Turabian StyleKołodziej-Hajdo, Marta, Artur Machno, Janusz Nesterak, and Michał Kowalski. 2025. "Application of Management Controlling in the Energy and Heating Sector: Diagnosis of Implementation Level and Identification of Development Barriers in the Context of Other Economic Sectors" Energies 18, no. 17: 4458. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18174458

APA StyleKołodziej-Hajdo, M., Machno, A., Nesterak, J., & Kowalski, M. (2025). Application of Management Controlling in the Energy and Heating Sector: Diagnosis of Implementation Level and Identification of Development Barriers in the Context of Other Economic Sectors. Energies, 18(17), 4458. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18174458