Integrating Energy Justice and SDGs in Solar Energy Transition: Analysis of the State Solar Policies of India

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Energy Transition, Justice, and SDGs

2.2. Existing Frameworks for Ensuring a Just Energy Transition

2.3. Justice-Oriented Analysis of Renewable Energy Policies and Projects

2.4. Research Gaps and Question

3. Methodology

3.1. Developing an Analytical Framework

3.2. Applying the Framework

3.2.1. Data Sources

3.2.2. Data Analysis

4. Analytical Framework

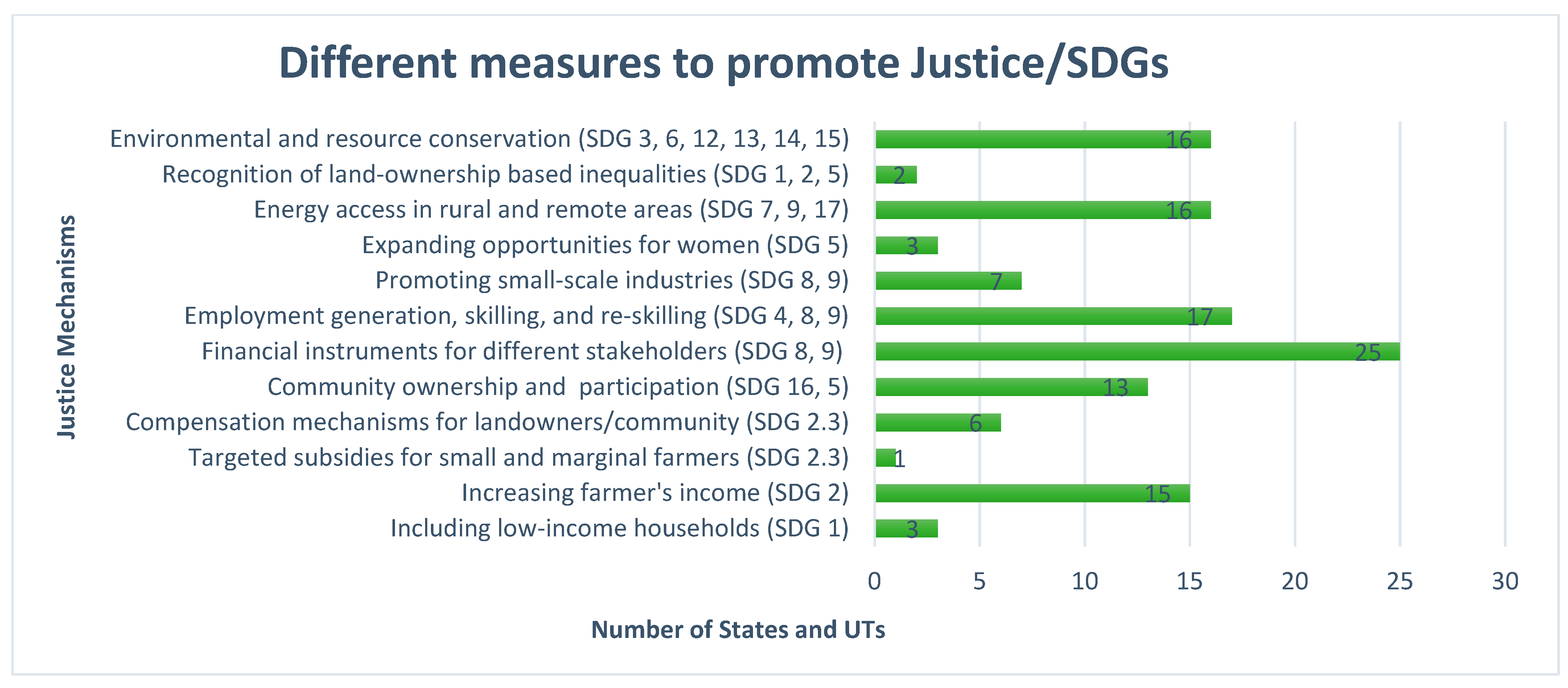

5. Results—How Do India’s Solar Policies Promote Justice?

5.1. Income Growth

5.1.1. Measures for Increasing the Income of Poor Households

5.1.2. Measures for Increasing the Income of Farmers

5.2. Enhancing Inclusion

5.2.1. Compensation Mechanisms for Landowners and the Community

5.2.2. Measures for Promoting Inclusive Decision-Making, Community Ownership, and Effective Participation

5.2.3. Inclusive Financial Mechanisms

5.3. Equal Opportunities and Outcomes

5.3.1. Measures for Promoting Employment Opportunities, Skill Development, and Promotion of Small-Scale Industries

5.3.2. Measures for Expanding Opportunities for Women

5.3.3. Measures for Increasing Energy Access, Rural Development, and Recognition of Land Ownership Inequalities

5.3.4. Measures for Environmental and Resource Conservation

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Dimension | Selected SDGs |

|---|---|

| Income Growth 10.1: By 2030, progressively achieve and sustain income growth of the bottom 40 per cent of the population at a rate higher than the national average | 1.1: By 2030, eradicate extreme poverty for all people everywhere, currently measured as people living on less than USD 1.25 a day 1.2: By 2030, reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women, and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions 1.3: Implement nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all, including floors, and by 2030, achieve substantial coverage of the poor and the vulnerable |

| 2.3: By 2030, double the agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers, in particular women, indigenous peoples, family farmers, pastoralists, and fishers, including through secure and equal access to land, other productive resources and inputs, knowledge, financial services, markets, and opportunities for value addition and non-farm employment | |

| Enhancing Inclusion 10.2: By 2030, empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all, irrespective of age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion, or economic or other status | 2.3: By 2030, double the agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers, in particular women, indigenous peoples, family farmers, pastoralists, and fishers, including through secure and equal access to land, other productive resources and inputs, knowledge, financial services, markets, and opportunities for value addition and non-farm employment |

| 5.5: Ensure women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making in political, economic, and public life 16.6: Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels 16.7: Ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory, and representative decision-making at all levels Other targets 16.10: Ensure public access to information and protect fundamental freedoms, in accordance with national legislation and international agreements | |

| 8.10: Strengthen the capacity of domestic financial institutions to encourage and expand access to banking, insurance, and financial services for all 9.3: Increase the access of small-scale industrial and other enterprises, in particular in developing countries, to financial services, including affordable credit, and their integration into value chains and markets 10.4: Adopt policies, especially fiscal, wage, and social protection policies, and progressively achieve greater equality | |

| Equality of Opportunity and Outcome 10.3: Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome, including by eliminating discriminatory laws, policies, and practices and promoting appropriate legislation, policies and action in this regard | 8.3: Promote development-oriented policies that support productive activities, decent job creation, entrepreneurship, creativity, and innovation, and encourage the formalization and growth of micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises, including through access to financial services 8.5: By 2030, achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value 8.6: By 2020, substantially reduce the proportion of youth not in employment, education, or training 8.8: Protect labor rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants, and those in precarious employment 9.2: Promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and, by 2030, significantly raise industry’s share of employment and gross domestic product, in line with national circumstances, and double its share in least developed countries |

| 9.3: Increase the access of small-scale industrial and other enterprises, in particular in developing countries, to financial services, including affordable credit, and their integration into value chains and markets 9.4: By 2030, upgrade infrastructure and retrofit industries to make them sustainable, with increased resource-use efficiency and a greater adoption of clean and environmentally sound technologies and industrial processes, with all countries taking action in accordance with their respective capabilities | |

| 4.3: By 2030, ensure equal access for all women and men to affordable and quality technical, vocational, and tertiary education, including university 4.4: By 2030, substantially increase the number of youth and adults who have relevant skills, including technical and vocational skills, for employment, decent jobs, and entrepreneurship 4.5: By 2030, eliminate gender disparities in education and ensure equal access to all levels of education and vocational training for the vulnerable, including persons with disabilities, indigenous peoples, and children in vulnerable situations Other targets: 4.7: By 2030, ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship, and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development 8.6, 8.8 | |

| 5.5: Ensure women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making in political, economic, and public life 5.c: Adopt and strengthen sound policies and enforceable legislation for the promotion of gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls at all levels Other targets: 1.b: Create sound policy frameworks at the national, regional, and international levels, based on pro-poor and gender-sensitive development strategies, to support accelerated investment in poverty eradication actions 5.4: Recognize and value unpaid care and domestic work through the provision of public services, infrastructure, and social protection policies and the promotion of shared responsibility within the household and the family as nationally appropriate 5.b: Enhance the use of enabling technology, in particular information and communications technology, to promote the empowerment of women | |

| 7.1: By 2030, ensure universal access to affordable, reliable, and modern energy services 9.1: Develop quality, reliable, sustainable, and resilient infrastructure, including regional and transborder infrastructure, to support economic development and human well-being, with a focus on affordable and equitable access for all 17.17: Encourage and promote effective public, public–private, and civil society partnerships, building on the experience and resourcing strategies of partnerships | |

| 1.4: By 2030, ensure that all men and women, in particular the poor and the vulnerable, have equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to basic services, ownership and control over land and other forms of property, inheritance, natural resources, appropriate new technology, and financial services, including microfinance 2.3: By 2030, double the agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers, in particular women, indigenous peoples, family farmers, pastoralists, and fishers, including through secure and equal access to land, other productive resources and inputs, knowledge, financial services, markets, and opportunities for value addition and non-farm employment 5.a: Undertake reforms to provide women equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to ownership and control over land and other forms of property, financial services, inheritance, and natural resources, in accordance with national laws | |

| 3.9: By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water, and soil pollution and contamination 6.3: By 2030, improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimizing release of hazardous chemicals and materials, halving the proportion of untreated wastewater and substantially increasing recycling and safe reuse globally 11:6: By 2030, reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including by paying special attention to air quality and municipal and other waste management 12.4: By 2020, achieve the environmentally sound management of chemicals and all wastes throughout their life cycle, in accordance with agreed international frameworks, and significantly reduce their release to air, water, and soil in order to minimize their adverse impacts on human health and the environment 13.2: Integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies, and planning 14.1: By 2025, prevent and significantly reduce marine pollution of all kinds, in particular from land-based activities, including marine debris and nutrient pollution Other targets: 1.5: By 2030, build the resilience of the poor and those in vulnerable situations and reduce their exposure and vulnerability to climate-related extreme events and other economic, social, and environmental shocks and disasters 11.b: By 2020, substantially increase the number of cities and human settlements adopting and implementing integrated policies and plans towards inclusion, resource efficiency, mitigation, and adaptation to climate change, resilience to disasters, and develop and implement, in line with the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, holistic disaster risk management at all levels | |

| 6.6: By 2020, protect and restore water-related ecosystems, including mountains, forests, wetlands, rivers, aquifers, and lakes 12.2: By 2030, achieve the sustainable management and efficient use of natural resources 12.5: By 2030, substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling, and reuse 12.a: Support developing countries to strengthen their scientific and technological capacity to move towards more sustainable patterns of consumption and production 14.5: By 2020, conserve at least 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas, consistent with national and international law and based on the best available scientific information 15.1: By 2020, ensure the conservation, restoration, and sustainable use of terrestrial and inland freshwater ecosystems and their services, in particular forests, wetlands, mountains, and drylands, in line with obligations under international agreements 15.3: By 2030, combat desertification, restore degraded land and soil, including land affected by desertification, drought, and floods, and strive to achieve a land degradation-neutral world 15.4: Take urgent and significant action to reduce the degradation of natural habitats, halt the loss of biodiversity, and, by 2020, protect and prevent the extinction of threatened species Other targets: 15.2: By 2020, promote the implementation of sustainable management of all types of forests, halt deforestation, restore degraded forests, and substantially increase afforestation and reforestation globally 15.9: By 2020, integrate ecosystem and biodiversity values into national and local planning, development processes, poverty reduction strategies, and accounts |

| Criteria | Excluded SDG Targets |

|---|---|

| Not directly relevant to inequality | 2.2, 2.4, 2.a, 2.b, 3.1–3.6, 3.a, 6.3, 6.5, 7.2, 8.2, 8.9, 9.4, 11.4, 12.1, 12.3, 12.6, 12.7, 12.b, 13.1, 13.3, 14.2, 14.3, 14.4, 14.c, 16.4, 16.5 |

| Not relevant for solar energy transition | 2.1, 2.2, 2.5, 2.b, 2.c, 3.1–3.8, 3.a–3.d, 4.1, 4.2, 4.6, 4.a, 4.c, 5.1, 5.2, 5.3, 5.6, 6.2, 6.4, 6.5, 6.b, 8.7, 8.9, 9.c, 10.5, 10.6, 10.7, 10.c, 11.1, 11.2, 11.3, 11.4, 11.5, 11.7, 11.a, 11.c, 12.3, 12.6, 12.7, 12.8, 12.b, 13.3, 14.2, 14.4, 14.6, 14.7, 14.b, 15.4, 15.7, 15.8, 15.c, 16.1, 16.2, 16.3, 16.4, 16.8, 16.9, 16.a, 16.b, 17.10, 17.11, 17.12, 17.13, 17.14, 17.15, 17.18, 17.19 |

| Not relevant at the local level | 1.a, 2.a, 2.b, 3.a–3.d, 4.b, 4.c, 6.a, 7.3, 7.a, 7.b, 8.1, 8.4, 8.a, 8.b, 9.a, 9.b, 10.5, 10.6, 10.a, 10.b, 12.c, 13.a, 13.b, 14.3, 14.6, 14.a, 14.c, 15.a, 15.b, 16.8, 17.1–17.12, 17.13, 17.18, 17.19 |

| State/UT and Title of Policy | Operative Period | Solar Categories | Previous Policies | Other Policies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andhra Pradesh Andhra Pradesh Solar Power Policy-2018 | 2019–2024 | Solar power projects for sale to DISCOMs, captive use/third-party sale; solar parks; solar rooftop; solar pumps | Andhra Pradesh Solar Power Policy- 2015 | Wind Power Policy-2018; Wind–Solar Hybrid Power Policy-2018; Renewable Energy Export Policy-2020; Pumped Storage Power Promotion Policy-2022; Green Hydrogen and Green Ammonia Policy-2023 |

| Arunachal Pradesh Arunachal Pradesh State Electricity Regulatory Commission Draft Regulation for Rooftop Solar Grid Interactive systems based on Net Metering | 2016 | Grid-interactive rooftop solar | - | - |

| Assam Assam Renewable Energy Policy-2022 | 2022–2027 | Grid-connected solar (solar park, solar power plants for sale to DISCOM, for REC mechanism; solar plant in agriculture, captive solar power plant); rooftop (Industrial, residential, state government installations); off-grid (Solar pump, mini/microgrid, SHS, etc.); EV-charging infrastructure | ||

| Bihar Bihar Policy for Promotion of New and Renewable Energy Sources-2017 | 2017–2022 | Grid-connected solar (solar power plants for sale to DISCOM, for REC mechanism; sale to captive consumers/third party); grid-connected rooftop solar; solar parks; mini-grid projects; canal solar/floating solar; decentralized (street light, solar pumps, water heater, etc.) | Bihar Policy for Promotion of New and Renewable Energy Sources-2011 | |

| Chhattisgarh Chhattisgarh State Solar Energy Policy (only in regional language) | 2017–2027 | Wind Energy Policy-2006; Small Hydro Policy-2012 | ||

| Goa Goa State Solar Policy-2017 | 2017–2024 | Solar projects, ground-mounted and rooftop (prosumer, producer); solar power plants under REC; third-party sale; rooftop solar through RESCO | ||

| Gujarat Gujarat Renewable Energy Policy-2023 | 2023–2028 | Ground-mounted solar (solar park or outside), rooftop solar, floating/canal-based solar, wind–solar hybrid, RE projects under REC mechanism, | Gujarat Solar Power Policy 2021; Gujarat Wind Power Policy 2016; Gujarat Wind Solar Hybrid Power Policy-2018 | Small Hydel Policy-2016; Waste to Energy Policy-2022 |

| Haryana Haryana Solar Power Policy-2016 | 2016–until new policy | Ground-mounted solar (megawatt scale, capacity reservation, solar parks, canal-based); rooftop solar; solar pumps; decentralized and off-grid solar | Haryana Solar Power Policy-2014 | |

| Himachal Pradesh Himachal Energy Policy-2021 | 2021 | Grid-connected rooftop (net-metering and captive use), ground-mounted solar (small and large capacity, floating solar), wind-solar hybrid | Solar Power Policy-2016 | |

| Jharkhand Jharkhand State Solar Policy-2022 | 2022–2027 | Utility scale solar projects (solar park, non-park solar, floating solar, canal top); distributed solar projects (rooftop solar, captive and group captive, solar agriculture—solar plants, solar pumps); off-grid solar (model solar villages-min/microgrid, SHS, solar for livelihood, solar pump); integrated solar (EV-charging stations, hybrid RE) | Jharkhand State Solar Policy-2015 | |

| Karnataka Karnataka Renewable Energy Policy-2022–2027 | 2022–2027 | Grid-connected solar; rooftop solar; distributed solar (solarization of agriculture feeders and solar pumps); EV-charging station | ||

| Kerala Kerala Solar Energy Policy-2013 | 2013–until new policy | Grid-connected solar, off-grid, solar thermal | Renewable energy policy-2002 | |

| Madhya Pradesh Madhya Pradesh Renewable Energy Policy-2022 | 2022–2027 | Ground-mounted, floating solar, canal top; grid-connected RE projects (like Comp. A of PM-KUSUM scheme) | Policy for Decentralized RE Systems-2016 | |

| Maharashtra Transmission Linked/Non-Transmission Integrated Renewable Energy Strategy- 2020 (only in regional language) | 2020 | Non-Conventional Energy Generation Policy-2020 | ||

| Manipur Manipur Grid-Interactive Rooftop Solar Photo-Voltaic (SPV) Power Policy-2014 | 2015 | Grid-interactive rooftop solar | ||

| Meghalaya Meghalaya State Electricity Regulatory Commission (Rooftop Solar Grid Interactive systems based on Net metering) Regulations-2015 | 2015 | Grid-interactive rooftop solar | ||

| Mizoram Solar Power Policy of Mizoram-2017 | 2017–until further order | Grid-connected projects (under central govt., state govt., REC mechanism, captive generation, third-party sale); grid-connected rooftop; off-grid projects (SHS, solar lanterns, solar pack, solar pumps) | ||

| Nagaland | - | - | - | |

| Odisha Odisha Renewable Energy Policy-2022 | 2022–2030 | Land-based solar (solar park, non-park solar); rooftop solar, floating solar; canal top solar; distributed solar (grid-connected solar pumps, solar cookers, solar dryer, etc.); EV-charging stations; solar cities | ||

| Punjab New and Renewable Energy Sources of Energy (NRSE) Policy-2012 | 2012–until new policy | Rooftop solar; decentralized and off-grid (solar thermal, solar PV lighting system, SPV pumps) | New and Renewable Energy Sources of Energy (NRSE) Policy-2006 | |

| Rajasthan Rajasthan Renewable Energy Policy-2023 | 2023–until new policy | Grid-connected utility-scale (solar parks, sale to DISCOM, captive use, third party sale); rooftop solar, floating/canal solar; decentralized grid-connected; off-grid solar (pumps, stand-alone solar system) | Green Hydrogen Policy-2023; Biomass and Waste to Energy Policy-2023 | |

| Sikkim Grid Connected Rooftop Solar Photovoltaic System Policy for Sikkim-2019 | 2019–2022 | Grid-connected rooftop solar | ||

| Tamil Nadu Tamil Nadu Solar Energy Policy-2019 | 2019–until new policy | Grid feed-in (gross feed-in, consumer net feed-in); EVs; solar–thermal | Tamil Nadu Solar Energy Policy-2012 | |

| Telangana Telangana Solar Power Policy-2015 | 2015–2020 | Solar parks; Solar power projects (grid-connected for sale to DISCOMs, third-party sale, captive generation, solar thermal); rooftop solar (grid and off-grid); solar pump sets; off-grid | ||

| Tripura | - | - | - | |

| Uttarakhand Uttarakhand State Solar Policy-2023 | 2023–until new policy | Utility-scale solar, distributed solar (residential rooftop solar, community solar, solar villages, mini/micro-grids, solar for livelihood, commercial rooftop, captive and third party, institutional, agricultural grid and off-grid solar installations, and solar pumps) | Uttarakhand Solar Energy Policy, 2013 | |

| Uttar Pradesh Uttar Pradesh Solar Energy Policy-2022 | 2022–2027 (or till new policy, whichever is earlier) | Utility-scale solar projects; rooftop solar (residential, non-residential), distributed solar (solar pumps, feeder solarization); floating/canal solar; off-grid solar (solar plants, solar lights, solar pack system, solar pump, etc.) | ||

| West Bengal West Bengal Policy on Co-Generation and Generation of Electricity from Renewable Sources of Energy-2012 | 2012–2022 | Grid-connected utility scale; rooftop solar and small projects; distributed solar | ||

| Andaman and Nicobar Islands Joint Electricity Regulatory Commission for the State of Goa and Union Territories (Draft Solar PV Grid Interactive System based on Net Metering) Regulations-2019 | 2019 | Grid-connected land/rooftop solar | ||

| Chandigarh Joint Electricity Regulatory Commission for the State of Goa and Union Territories (Draft Solar PV Grid Interactive System based on Net Metering) Regulations-2019 | 2019 | Grid-connected land/rooftop solar | ||

| Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu Renewable Energy Policy-2024 for U.T. of Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu | 2024–until new policy | Solar PV rooftop, ground-mounted, floating | ||

| The Government of NCT of Delhi Delhi Solar Policy, 2016 | 2016–2020 | Grid-connected rooftop solar | ||

| Jammu and Kashmir Solar Power Policy for Jammu and Kashmir-2013 | 2013–until new policy | Solar power plants | Policy for Grid Connected Rooftop Solar Photovoltaic Power Plant-2016 (Net-Metering Based); Policy for Development of Micro/Mini-Hydro Power Project-2011 | |

| Ladakh | N/A | |||

| Lakshadweep Joint Electricity Regulatory Commission for the State of Goa and Union Territories (Draft Solar PV Grid Interactive System based on Net Metering) Regulations-2019 | 2019 | Grid-connected land/rooftop solar | ||

| Puducherry Solar Energy Policy-2015 | 2015–until new policy | Grid-connected solar PV (rooftop, solar parks), solar–wind hybrid, solar thermal, solar pumps |

| Sub-Dimension/Indicator | Specific Mechanisms/Provision | States/UT |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanisms for low-income households | Subsidies for low-income households Standalone solar home systems for BPL households Exemption of BPL and agricultural consumers from tax | Jharkhand Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh Bihar |

| Mechanisms for increasing and diversifying farmer’s income | Promotion of solar pumps, sale of surplus energy through grid-connected solar pumps Setting up small solar projects by farmers | Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Bihar, Haryana, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Mizoram, Odisha, Punjab, Puducherry, Rajasthan, Telangana, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh Assam, Bihar, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Rajasthan |

| Targeted subsidies for small and marginal farmers | Additional subsidy to ST and marginalized farmers for solar pumps | Uttar Pradesh |

| Compensation mechanisms for landowners and community | Payment of development charges to support rehabilitation and community development Revenue sharing model for tribal land Special provisions for communidade and tribal land | Telangana, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, West Bengal Kerala Goa, Kerala |

| Inclusive decision-making, community ownership and participation | Involvement of different ministries, departments, and organizations Allowing projects to be installed by groups of individuals/farmers/cooperatives (collective generation) Promotion of community-owned projects Representation of women in model solar villages | Jharkhand, Mizoram, Punjab, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttarakhand Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Chandigarh, Lakshadweep Bihar, Jharkhand, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Uttarakhand Jharkhand, Uttarakhand |

| Financial instruments as per needs of different stakeholders | Additional state subsidies for solar projects (small, rooftop, solar pumps) Interest-free loan for small prosumers; subsidy for standalone systems Generation-based incentive Virtual-net metering for rooftop solar RESCO Model/Third-party owned Other incentives for the promotion of solar (Panchayat, farmers) Innovative business models for decentralized solar (community subscription, pay-as-you-go) | Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Bihar, Goa, Haryana, Jharkhand, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh Goa Delhi, Sikkim, West Bengal Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu, Delhi, Jharkhand, Puducherry, Sikkim, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Bihar, Goa, Haryana, Jharkhand, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Rajasthan, Odisha, Sikkim, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu, Delhi, Puducherry, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Chandigarh, Lakshadweep Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan Jharkhand |

| Employment opportunities and skill development | Employment generation and/or skill development as one of the objectives Reserving employment opportunities for ‘bona fide residents’, state subjects Separate section on skill and capacity building (capacity building and training sessions) Re-skilling of mine workers Skilling of jail inmates | Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu, Delhi, Gujarat, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, Jharkhand, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Mizoram, Odisha, Rajasthan, Sikkim, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Jammu and Kashmir Bihar, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand Uttar Pradesh |

| Promotion of small-scale industries | Incentives to new or domestic manufacturing industries Incentives under the Micro-, Small, and Medium Enterprise (MSME) policy | Andhra Pradesh, Jharkhand, Telangana, Himachal Pradesh Rajasthan, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh |

| Equal Opportunities for Women | Creating livelihood opportunities for women Gender-inclusive skill training | Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttarakhand Jharkhand, Uttarakhand |

| Increased energy access and infrastructure for rural development | Promotion of decentralized solar applications in remote areas Non-electricity applications (solar cooker, heater, desalination, dryer) Prioritizing tribal areas for off-grid applications Special consideration for rural targets Provision to provide access to infrastructure (roads, water) to the local population | Assam, Bihar, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Mizoram, Odisha, Punjab, Rajasthan, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu Bihar, Haryana, Himachal, Jharkhand, Kerala, Odisha, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal Uttar Pradesh Sikkim Himachal Pradesh |

| Recognition of land ownership inequalities | Special mechanisms for communidade and tribal land | Goa, Kerala |

| Environmental and resource conservation | Promotion of floating solar for preventing water loss Promotion and incentivization of technologies for water conservation R&D for the end-of-life management of solar PV modules | Assam, Bihar, Delhi, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Chandigarh, Lakshadweep Jharkhand Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttarakhand |

References

- Siciliano, G.; Wallbott, L.; Urban, F.; Dang, A.N.; Lederer, M. Low-carbon Energy, Sustainable Development, and Justice: Towards a Just Energy Transition for the Society and the Environment. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 1049–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCollum, D.L.; Echeverri, L.G.; Busch, S.; Pachauri, S.; Parkinson, S.; Rogelj, J.; Krey, V.; Minx, J.C.; Nilsson, M.; Stevance, A.-S.; et al. Connecting the Sustainable Development Goals by Their Energy Inter-Linkages. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 033006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuso Nerini, F.; Tomei, J.; To, L.S.; Bisaga, I.; Parikh, P.; Black, M.; Borrion, A.; Spataru, C.; Castán Broto, V.; Anandarajah, G.; et al. Mapping Synergies and Trade-Offs Between Energy and the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Energy 2017, 3, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobuţă, G.I.; Höhne, N.; Van Soest, H.L.; Leemans, R. Transitioning to Low-Carbon Economies under the 2030 Agenda: Minimizing Trade-Offs and Enhancing Co-Benefits of Climate-Change Action for the SDGs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, P.; Mainali, B.; Dhakal, S. Focus on Climate Action: What Level of Synergy and Trade-Off Is There between SDG 13; Climate Action and Other SDGs in Nepal? Energies 2023, 16, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägele, R.; Iacobuţă, G.I.; Tops, J. Addressing Climate Goals and the SDGs Through a Just Energy Transition? Empirical Evidence from Germany and South Africa. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2022, 19, 85–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markkanen, S.; Anger-Kraavi, A. Social Impacts of Climate Change Mitigation Policies and Their Implications for Inequality. Clim. Policy 2019, 19, 827–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villavicencio Calzadilla, P.; Mauger, R. The UN’s New Sustainable Development Agenda and Renewable Energy: The Challenge to Reach SDG7 While Achieving Energy Justice. J. Energy Nat. Resour. Law 2018, 36, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MNRE Physical Achievements. Available online: https://mnre.gov.in/en/physical-progress/ (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Carley, S.; Konisky, D.M. The Justice and Equity Implications of the Clean Energy Transition. Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, R.G.; Raimi, D. The New Climate Math: Energy Addition, Subtraction, and Transition 2018. Available online: https://www.rff.org/publications/issue-briefs/the-new-climate-math-energy-addition-subtraction-and-transition/ (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Von Stechow, C.; Minx, J.C.; Riahi, K.; Jewell, J.; McCollum, D.L.; Callaghan, M.W.; Bertram, C.; Luderer, G.; Baiocchi, G. 2 °C and SDGs: United They Stand, Divided They Fall? Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 034022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuso Nerini, F.; Sovacool, B.; Hughes, N.; Cozzi, L.; Cosgrave, E.; Howells, M.; Tavoni, M.; Tomei, J.; Zerriffi, H.; Milligan, B. Connecting Climate Action with Other Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain 2019, 2, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.; Cowie, A.; Babiker, M.; Leip, A.; Smith, P. Co-Benefits and Trade-Offs of Climate Change Mitigation Actions and the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, J. Just Transitions for the Miners: Labor Environmentalism in the Ruhr and Appalachian Coalfields. New Political Sci. 2017, 39, 218–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffron, R.J.; McCauley, D. What Is the ‘Just Transition’? Geoforum 2018, 88, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sareen, S.; Nordholm, A.J. Sustainable Development Goal Interactions for a Just Transition: Multi-Scalar Solar Energy Rollout in Portugal. Energy Sources Part B Econ. Plan. Policy 2021, 16, 1048–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, K.; McCauley, D.; Heffron, R.; Stephan, H.; Rehner, R. Energy Justice: A Conceptual Review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 11, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Dworkin, M.H. Energy Justice: Conceptual Insights and Practical Applications. Appl. Energy 2015, 142, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, O.W.; Han, J.Y.-C.; Knight, A.-L.; Mortensen, S.; Aung, M.T.; Boyland, M.; Resurrección, B.P. Intersectionality and Energy Transitions: A Review of Gender, Social Equity and Low-Carbon Energy. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 70, 101774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, D.; Ramasar, V.; Heffron, R.J.; Sovacool, B.K.; Mebratu, D.; Mundaca, L. Energy Justice in the Transition to Low Carbon Energy Systems: Exploring Key Themes in Interdisciplinary Research. Appl. Energy 2019, 233–234, 916–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. Guidelines for a Just Transition Towards Environmentally Sustainable Economies and Societies for All; International Labour Organization (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA. World Energy Transitions Outlook 2023: 1.5 °C Pathway; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Climate Justice Aliiance Just Transition Principles. Available online: https://climatejusticealliance.org/just-transition-2/ (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Boateng, D.; Bloomer, J.; Morrissey, J. Where the Power Lies: Developing a Political Ecology Framework for Just Energy Transition. Geogr. Compass 2023, 17, e12689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Barnacle, M.L.; Smith, A.; Brisbois, M.C. Towards Improved Solar Energy Justice: Exploring the Complex Inequities of Household Adoption of Photovoltaic Panels. Energy Policy 2022, 164, 112868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum (WEF) Just Transition Framework. Available online: https://intelligence.weforum.org/topics/a1G680000008hNeEAI) (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- GIZ Just Orientation Framework 2023. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/GIZ%20Just%20Transition%20Orientation%20Framework_Final.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Carbon Trust. Supporting a Rapid, Just and Equitable Transition Away from Coal Frameworks and Guidance to Support a Structured Planning Approach for a Just Coal-to-Clean Energy Transition; Carbon Trust: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, D.; Bryant, G.; Pillai, P. Who Wins and Who Loses from Renewable Energy Transition? Large-Scale Solar, Land, and Livelihood in Karnataka, India. Globalizations 2023, 20, 1328–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, U.; Poojary, V.; Jain, T.; Kelkar, U. Negotiating a Just Transition The Case of Utility-Scale Solar in Semi-Arid Southern India. In Just Transitions Gender and Power in India’s Climate Politics; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 170–191. ISBN 978-1-003-04837-4. [Google Scholar]

- Arndt, C.; Arent, D.; Hartley, F.; Merven, B.; Mondal, A.H. Faster Than You Think: Renewable Energy and Developing Countries. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2019, 11, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Bagchi, K. Is Off-Grid Residential Solar Power Inclusive? Solar Power Adoption, Energy Poverty, and Social Inequality in India. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 82, 102314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Heffron, R.J.; McCauley, D.; Goldthau, A. Energy Decisions Reframed as Justice and Ethical Concerns. Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 16024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, C.L.; Baker, J.S.; Shaw, B.K.; Kondash, A.J.; Leiva, B.; Castellanos, E.; Wade, C.M.; Lord, B.; Van Houtven, G.; Redmon, J.H. How Will Renewable Energy Development Goals Affect Energy Poverty in Guatemala? Energy Econ. 2021, 104, 105665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottram, H. Injustices in Rural Electrification: Exploring Equity Concerns in Privately Owned Minigrids in Tanzania. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 93, 102829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanke, F.; Lowitzsch, J. Empowering Vulnerable Consumers to Join Renewable Energy Communities—Towards an Inclusive Design of the Clean Energy Package. Energies 2020, 13, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordholm, A.; Sareen, S. Scalar Containment of Energy Justice and Its Democratic Discontents: Solar Power and Energy Poverty Alleviation. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 626683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, F.; Neumann, M.; Elsner, C.; Claar, S. Assessing African Energy Transitions: Renewable Energy Policies, Energy Justice, and SDG 7. PaG 2021, 9, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.R.; Bhatia, P. How Just and Democratic Is India’s Solar Energy Transition?: An Analysis of State Solar Policies in India. In Climate Justice in India; Kashwan, P., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 50–73. ISBN 978-1-009-17190-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ukoba, K.; Yoro, K.O.; Eterigho-Ikelegbe, O.; Ibegbulam, C.; Jen, T.-C. Adaptation of Solar Energy in the Global South: Prospects, Challenges and Opportunities. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubash, N.K. The Politics of Climate Change in India: Narratives of Equity and Cobenefits. WIREs Clim. Change 2013, 4, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, I.; Sivaraman, S. Gender Inequality and Gender Gap: An Overview of the Indian Scenario. Gend. Issues 2023, 40, 232–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, R. Intersectionality of Gender and Other Forms of Identity: Dilemmas and Challenges Facing Women in India. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2013, 28, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. Global Gender Gap 2024; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-gender-gap-report-2024/digest/ (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- MNRE State Policies. Available online: https://mnre.gov.in/policies-and-regulations/policies-and-guidelines/state/ (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Stemler, S.E. Content Analysis. In Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences; Scott, R.A., Kosslyn, S.M., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–14. ISBN 978-1-118-90077-2. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 2nd ed.; [Nachdr.]; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-0-7619-1544-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ingole, C.K. Do Off-Grid Solar Energy Based Productive Activities Increase Income of Beneficiaries: An Impact Evaluation Using PSM and DID Techniques. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2024, 83, 101567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standal, K.; Feenstra, M. Gender and Solar Energy in Indias Low-Carbon Energy Transition. In Research Handbook on Energy and Society; Webb, J., Wade, F., Tingey, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021; pp. 141–153. ISBN 978-1-83910-071-0. Available online: https://www.elgaronline.com/edcollchap/book/9781839100710/book-part-9781839100710-20.xml (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Yenneti, K.; Day, R. Distributional Justice in Solar Energy Implementation in India: The Case of Charanka Solar Park. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 46, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, E. The Impact of Solar Water Pumps on Energy-Water-Food Nexus: Evidence from Rajasthan, India. Energy Policy 2019, 129, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Closas, A.; Rap, E. Solar-Based Groundwater Pumping for Irrigation: Sustainability, Policies, and Limitations. Energy Policy 2017, 104, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Y.; Stephens, J.C. Energy Justice Through Solar: Constructing and Engaging Low-Income Households. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 632020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, H.P. “Lead the District into the Light”: Solar Energy Infrastructure Injustices in Kerala, India. Glob. Transit. 2019, 1, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenneti, K.; Day, R. Procedural (in)Justice in the Implementation of Solar Energy: The Case of Charanaka Solar Park, Gujarat, India. Energy Policy 2015, 86, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Majid, M.A. Renewable Energy for Sustainable Development in India: Current Status, Future Prospects, Challenges, Employment, and Investment Opportunities. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2020, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl-Martinez, R.; Stephens, J.C. Toward a Gender Diverse Workforce in the Renewable Energy Transition. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2016, 12, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mininni, G.M. The Barefoot College ‘Eco-Village’ Approach to Women’s Entrepreneurship in Energy. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2022, 42, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, K.; Shrivastava, M.K.; Hakhu, A.; Bajaj, K. A Two-Step Approach to Integrating Gender Justice into Mitigation Policy: Examples from India. Clim. Policy 2020, 20, 800–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, R. Illuminant Intersections: Injustice and Inequality Through Electricity and Water Infrastructures at the Gujarat Solar Park in India. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 82, 102309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenda, A.M.; Behrsin, I.; Disano, F. Renewable Energy for Whom? A Global Systematic Review of the Environmental Justice Implications of Renewable Energy Technologies. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 71, 101837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Sharma, T.; Gupta, A.K. End-of-Life Management of Solar PV Waste in India: Situation Analysis and Proposed Policy Framework. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 153, 111774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Jharkhand. Jharkhand State Solar Policy 2022; Government of Jharkhand: Ranchi, India, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Uttar Pradesh. Uttar Pradesh Solar Energy Policy-2022; Government of Uttar Pradesh: Lucknow, India, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Bihar. Bihar Policy for Promotion of New and Renewable Energy Sources 2017; Government of Bihar: Patna, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Telangana. Telangana Solar Power Policy 2015; Government of Telangana: Hyderabad, India, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Uttarakhand. Uttarakhand State Solar Policy, 2023; Government of Uttarakhand: Dehradun, India, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- HIMURJA. Himachal Pradesh Renewable Energy Policy-2021; HIMURJA: Shimla, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Government of West Bengal. Policy on Co-Generation and Generation of Electricity from Renewable Sources of Energy; Government of West Bengal: Kolkata, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Kerala. Kerala Solar Energy Policy 2013; Government of Kerala: Thiruvanthapuram, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- GOA ENERGY DEVELOPMENT AGENCY(GEDA). GOA STATE SOLAR POLICY-2017; GEDA: Panaji, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Madhya Pradesh. Madhya Pradesh Renewable Energy Policy—2022; Government of Madhya Pradesh: Bhopal, India, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Assam. Assam Renewable Energy Policy, 2022; Government of Assam: Dispur, India, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Science and Technology. Solar Power Policy for Jammu and Kashmir; Department of Science and Technology: Jammu, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Andhra Pradesh. Andhra Pradesh Solar Power Policy-2018; Government of Andhra Pradesh: Hyderabad, India, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Gujarat. Gujarat Renewable Energy Policy-2023; Government of Gujarat: Ahmedabad, India, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Rajasthan. Rajasthan Renewable Energy Policy, 2023; Government of Rajasthan: Jaipur, India, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Haldar, S.; Peddibhotla, A.; Bazaz, A. Analysing Intersections of Justice with Energy Transitions in India—A Systematic Literature Review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 98, 103010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, K.; Sovacool, B.K.; McCauley, D. Humanizing Sociotechnical Transitions Through Energy Justice: An Ethical Framework for Global Transformative Change. Energy Policy 2018, 117, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menton, M.; Larrea, C.; Latorre, S.; Martinez-Alier, J.; Peck, M.; Temper, L.; Walter, M. Environmental Justice and the SDGs: From Synergies to Gaps and Contradictions. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 1621–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SDG | Synergies | Trade-Offs |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 1: No Poverty | Access to modern energy services can alleviate poverty, and off-grid solar solutions can enhance energy access in remote areas. | New renewable energy policies can increase electricity prices, impacting the poor. |

| SDG 2: Zero Hunger | Modern energy services boost agricultural productivity, essential for food security. | Large-scale bioenergy and solar projects can compete for land resources, posing a threat to food security |

| SDG 5: Gender Equality | Improved lighting enhances women’s security, while access to modern energy can create business opportunities for women. | Women may not have equal access to ‘technical’ opportunities created in renewable energy projects due to societal norms. |

| SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth | Renewable energy expansion generates direct jobs in infrastructure and indirect employment by enhancing energy access and economic activity. | The transition to renewable energy may pose a threat to jobs for fossil fuel workers. |

| SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities | Small-scale renewable energy plants can facilitate community engagement and boost their income. | Developing renewable energy infrastructure can threaten communities and lead to their displacement. |

| Existing Frameworks | Elements/Dimensions | Linkages with SDGs | Linkages with Justice/(In)Equality |

|---|---|---|---|

| ILO [22] | Nine policy areas: macroeconomic and growth, industrial and sectoral, enterprise, skill development, occupational safety and health, social protection, active labor market, social dialogue, and tripartism | Just transition is viewed in the context of sustainable development | The framework promotes social inclusion and reducing inequalities |

| Climate Justice Alliance Framework [24] | Extractive economy to regenerative economy. Caring and sacredness; ecological and social well-being; deep democracy; cooperation; regeneration | A regenerative economy is essentially a sustainable economy | Social equity and justice are aims of a just transition |

| IRENA [23] | Three policy pillars: deployment; integration; enabling | The proposed policies related to livelihood, skill development, labor, and finance have linkages with different SDGs | Inclusion is a key element of the framework |

| World Economic Forum [27] | Key elements: minimizing impacts on workers, shifting to sustainable practices, maximizing benefits to the environment, providing access to affordable and clean energy, and creating green jobs | It argues that interactions between climate goals and well-being should be achieved | It recognizes the disproportionate impacts of climate disasters on developing countries |

| GIZ [28] | Seven key principles: no climate impact; leaving no one behind; inclusive and transparent decision-making; tailor-made solutions; access to multiple people; focus on affected regions; long-term and flexible services | ‘Leaving no one behind’ is one of the key principles | Defines just transition as a ‘socially’ just strategy that improves living conditions equitably |

| Carbon Trust [29] | Three key principles: recognizing socio-economic inequalities; inclusive decision-making; equitable distribution of costs and benefits | The proposed policy solutions related to livelihood, skilling, and finance are related to different SDGs | Reducing inequalities and equitable distribution are core principles |

| Heffron and McCauley [16] | JUST: Justice (distributive, procedural, restorative); Universal (recognition, cosmopolitanism); Space; Time | Clean energy and climate action are important elements for a just transition and the SDGs | Just transition is defined in the context of inequality |

| Sovacool and Dworkin [19] | Nine energy justice principles: availability, affordability, due process, transparency, sustainability, intragenerational and intergenerational equity, responsibility | Sustainability is one of the principles, aligned with the SDG Agenda | Derived from energy justice tenets |

| Siciliano et al. [1] | Integrates low-carbon energy transition, energy justice, and SDGs | Explicitly links different SDGs to the impacts of low-carbon energy transition | Energy justice is used as an evaluative template |

| Haegele et al. [6] | Integrates energy justice tenets with ILO’s commitments and SDGs | Different SDGs are core of the framework | Inequality and justice principles are part of the framework |

| Boateng et al. [25] | Energy justice (distributive, procedural, recognition) and socio-technical innovations | The framework ensures a ‘sustainable’ energy transition | Inclusion is a key element of the framework |

| Themes | Codes | Sub-Codes |

|---|---|---|

| Income Growth |

|

|

| Inclusion |

|

|

| Equality of Opportunity and Outcomes |

|

|

| Inequality Dimensions | Sub-Dimensions | Indicators | Relevant SDG Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Income Growth (T10.1) | Increasing the income of the poor and eradicating poverty | Mechanisms to provide new income opportunities | 1.1, 1.2, 1.3 |

| Mechanisms for low-income households | |||

| Increasing the income of farmers | Mechanisms to increase and diversify farmers’ income | 2.3 | |

| Targeted subsidies for small-scale farmers | |||

| Enhancing Inclusion (T10.2) | Inclusion of the poor and vulnerable | Compensation mechanisms for owners and communities (landless and pastoralists) dependent on land | 2.3 |

| Inclusive governance | Inclusive decision-making, community ownership, and effective participation of women/marginalized, and mechanisms to remove barriers of inclusion | 16.6, 16.7, 16.10, 5.5 | |

| Inclusive finance | Financial instruments as per the needs of stakeholders | 8.10, 9.3, 10.4 | |

| Equality of Opportunity and Outcomes (T10.3) | Equitable employment and entrepreneurship opportunities; Skill development and capacity building | Creation of quality, safe, long-term, skilled, and unskilled jobs and entrepreneurship opportunities | 8.3, 8.5, 8.6, 8.8, 9.2 |

| Mechanisms for skilling, re-skilling of workers | 4.3, 4.4, 4.5, 8.6, 8.8 (4.7) | ||

| Mechanisms for promoting small-scale industries | 8.3, 9.2, 9.3, 9.4 | ||

| Equal opportunities for women and promoting gender justice | Mechanisms to create equal opportunities for women and promote gender justice | 5.5, 5.c (1.b, 5.4, 5.b) | |

| Ensuring resource access, recognition of resource inequalities | Increased energy access and affordability, and promotion of infrastructure for rural development | 7.1, 9.1, 17.17 | |

| Recognition of land-ownership-based inequalities | 1.4, 2.3, 5.a | ||

| Environmental and resource conservation | Mechanisms to reduce local pollution (air, water, land, noise) and GHG emissions | 3.9, 6.3, 11.6, 12.4, 13.2, 14.1 (1.5, 11.b) | |

| Mechanisms to conserve natural resources, biodiversity, and waste management | 6.6, 12.2, 12.5, 12.a, 14.5, 15.1, 15.3, 15.4 (15.2, 15.9) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Batra, B.; Standal, K.; Aamodt, S.; Sarangi, G.K.; Shrivastava, M.K. Integrating Energy Justice and SDGs in Solar Energy Transition: Analysis of the State Solar Policies of India. Energies 2025, 18, 3952. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18153952

Batra B, Standal K, Aamodt S, Sarangi GK, Shrivastava MK. Integrating Energy Justice and SDGs in Solar Energy Transition: Analysis of the State Solar Policies of India. Energies. 2025; 18(15):3952. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18153952

Chicago/Turabian StyleBatra, Bhavya, Karina Standal, Solveig Aamodt, Gopal K. Sarangi, and Manish Kumar Shrivastava. 2025. "Integrating Energy Justice and SDGs in Solar Energy Transition: Analysis of the State Solar Policies of India" Energies 18, no. 15: 3952. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18153952

APA StyleBatra, B., Standal, K., Aamodt, S., Sarangi, G. K., & Shrivastava, M. K. (2025). Integrating Energy Justice and SDGs in Solar Energy Transition: Analysis of the State Solar Policies of India. Energies, 18(15), 3952. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18153952