Analyze the Temporal and Spatial Distribution of Carbon Capture in Sustainable Development of Work

Abstract

1. Introduction

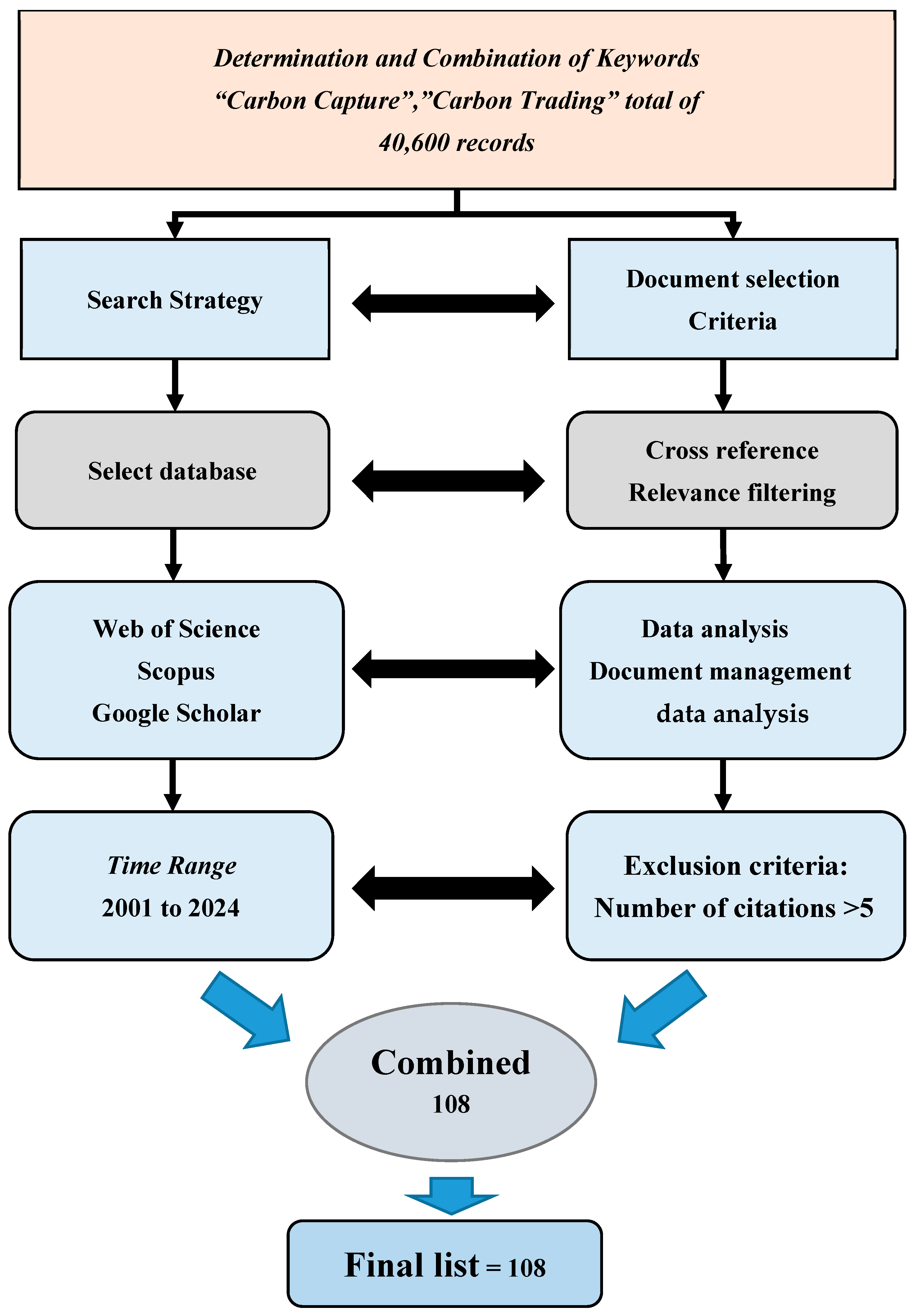

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Keyword Query

2.2. Literature Screening and Analysis Steps

- (1)

- Database Search:

- Using three major academic databases, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus, we conducted a comprehensive search with the keywords “carbon trading” and “carbon capture”, initially obtaining 40,600 related documents.

- (2)

- Screening Process

- Time frame: Limited to documents published from January 2004 to June 2024.

- Preliminary screening: Conducted based on titles, abstracts, and keywords to narrow down to approximately 40,000 documents to ensure the efficiency of the screening process.

- (3)

- Cross-referencing and Relevance Filtering

- Utilized the cross-referencing features within the databases for mutual referencing and relevance filtering of the documents.

- (4)

- Keyword Search

- For the preliminarily screened documents, performed more specific keyword searches, expanding the keyword range to CCS, CCU, “carbon trading market”, and other related fields to enhance screening precision.

- (5)

- Trend Analysis

- Used trend analysis tools to analyze the selected documents to determine research trends and development status of carbon capture and carbon trading.

- In the field of carbon capture technology research, the selection of appropriate keywords is paramount for capturing emerging trends and ensuring comprehensive coverage. For instance, in the realm of technological innovation, keywords such as “direct air capture”, “metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)”, “superbase-derived ionic liquids (SILs)”, and “mixed matrix membranes” are instrumental in identifying the latest advancements. In terms of economic and policy aspects, exploring keywords like “economic feasibility”, “policy framework”, “carbon trading”, and “quota allocation” aids in analyzing the economic and policy impacts. Regarding sustainability and environmental impact, terms like “sustainable solvents”, “phase-change absorbents”, and “nanoparticle-enhanced solvents” help locate relevant research projects. Additionally, regional and spatial distribution keywords such as “spatial distribution”, “regional climate adaptability”, and “site selection” should be used. For research on integrating carbon capture technology with renewable energy, terms like “renewable energy DAC”, “wind power”, and “U.S. 45Q tax credit” are essential. Through these strategies, researchers can effectively capture the latest trends in carbon capture technology, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the field.

- (6)

- Secondary Screening

- Peer-reviewed:Only peer-reviewed academic articles are selected, excluding any non-peer-reviewed documents such as conference abstracts, news reports, technical reports, and white papers.

- Publication source:Only articles published in journals indexed by SSCI, SCI and ESCI are considered. These journals possess high influence and reputation in their respective fields and can provide reliable research results.

- Relevance to the topic:Literature must directly relate to carbon capture technology. This includes, but is not limited to, the principles, methods, technological improvements, application cases, economic assessments, and environmental impact evaluations of carbon capture.

- Language:Only articles published in English-language journals are selected to ensure that researchers can fully comprehend and interpret the content.

- Rigorous research methods:Preference is given to articles employing strict and transparent research methods, such as those with clear experimental design, data analysis, and result interpretation.

- Citation frequency:The citation count of the literature is considered, with preference given to articles with high academic impact and citation rates. The minimum citation count is five. A secondary screening was conducted, focusing on documents with significant academic impact, high citation rates, and high journal impact factors, ultimately selecting 108 relevant SSCI, SCI and ESCI documents.

- (7)

- Software Tools Utilization

- Literature management: Managed and organized literature using EndNote and Zotero.

- Data analysis: Performed statistical analysis, including trend analysis and spatial analysis, using Microsoft Excel and R.

- Data visualization: Generated charts and graphs using Tableau for a more intuitive presentation of the analysis results.

3. Research Results: Temporal Trends

3.1. The Impact of Technology on Sustainable Development

3.2. Economic and Policy Considerations

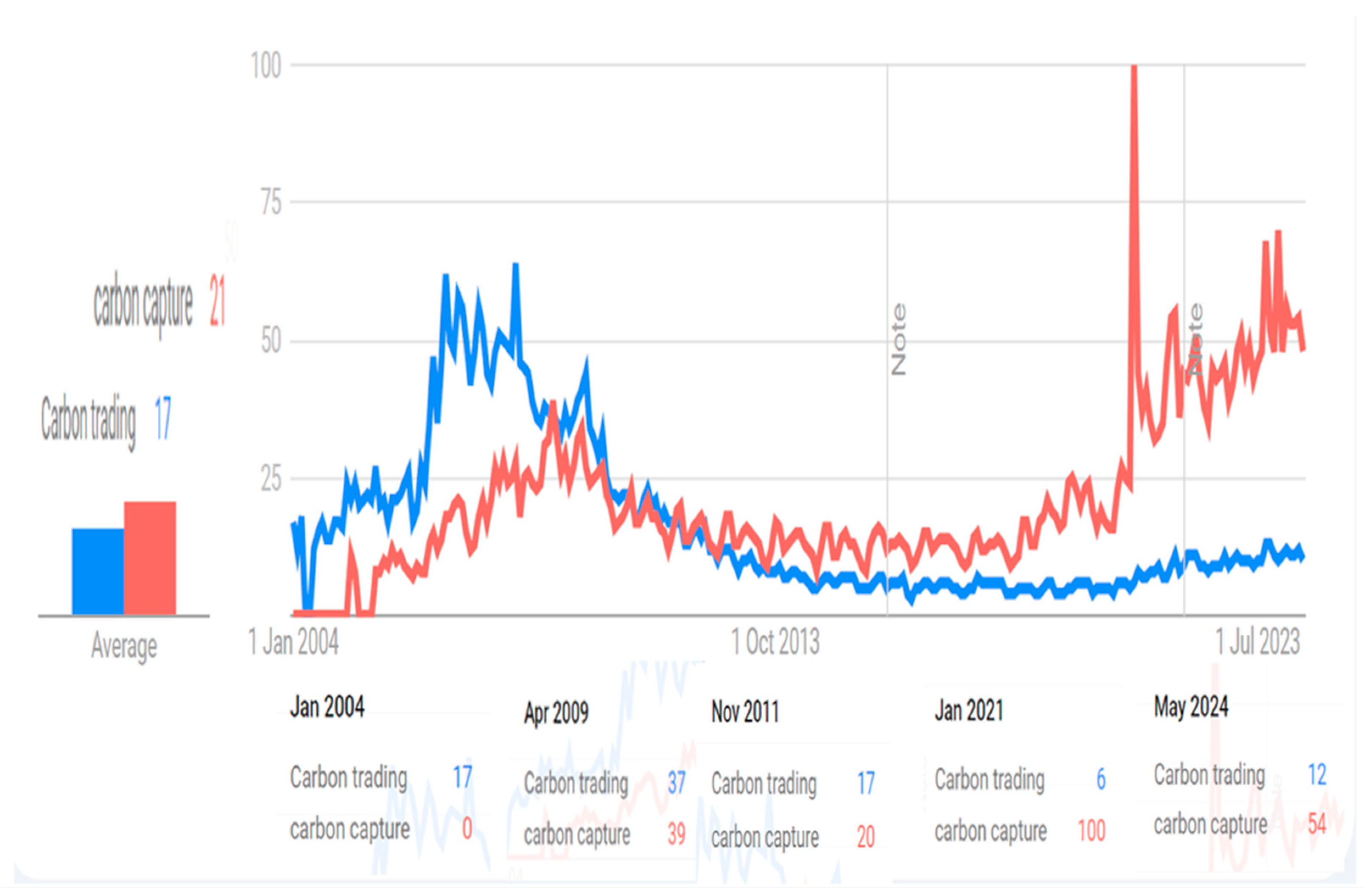

3.3. Trends in Carbon Trading and Carbon Capture

- Technological advancements: Innovative technologies such as hybrid matrix membranes, MOFs, and SILs have improved the efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and operability of CCS.

- Policy support: Policies like the US 45Q tax credit policy have provided economic incentives for CCS projects, boosting investor confidence.

- Strengthening of global climate policies: Under the framework of the Paris Agreement, countries have enhanced their climate targets, increasing the focus on CCS.

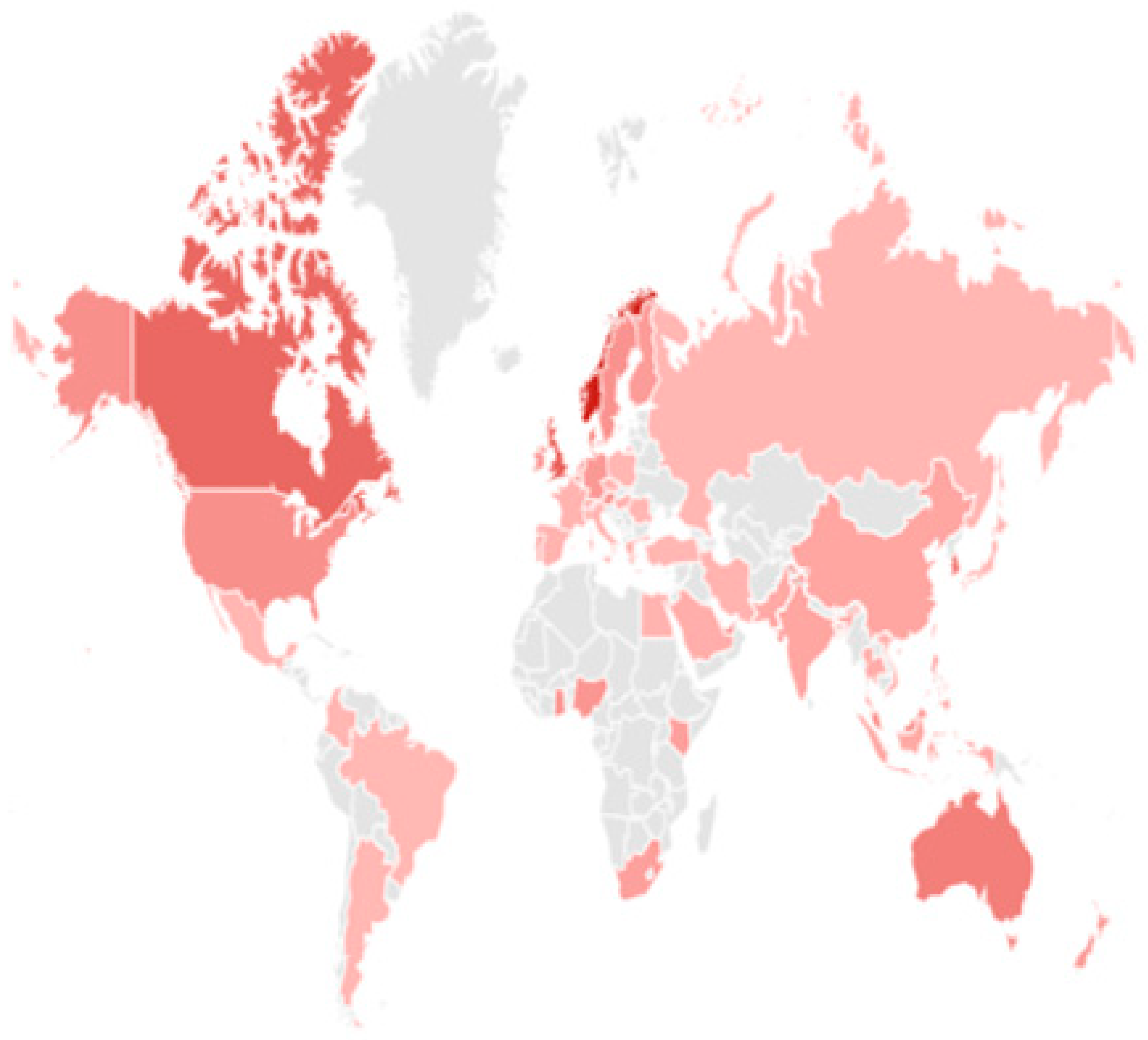

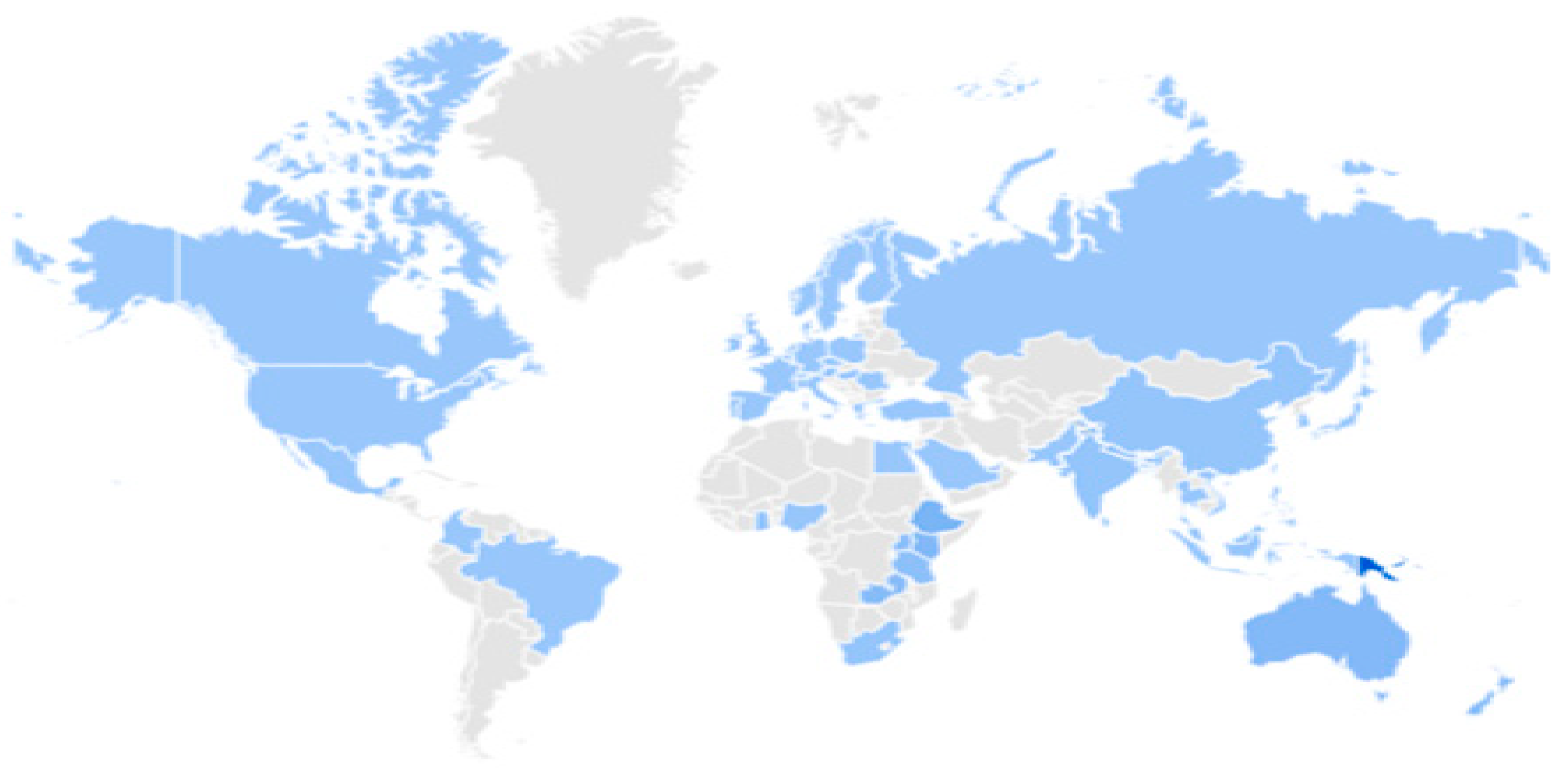

4. Research Results: Spatial Distribution

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vickers, V.L.; Hobbs, W.J.; Vemuri, S.; Todd, D.L. Fuel Resource Scheduling with Emission Constraints. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 1994, 9, 1531–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Xu, Y. Introducing Carbon Capture Science & Technology (CCST)! Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2021, 1, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, P. Timmo Krüger, Das Hegemonieprojekt Der Ökologischen Modernisierung: Die Konflikte Um Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) in Der Internationalen Klimapolitik. Int. Sociol. 2019, 34, 228–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, H. Fundamentals Point to Carbon Capture. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2019, 9, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Lv, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Qin, C.; Xu, S.; Wu, C. Integrated CO2 Capture and Utilization with CaO-Alone for High Purity Syngas Production. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2021, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, I.; Galán-Martín, Á.; Pérez-Ramírez, J.; Guillén-Gosálbez, G. Trade-Offs between Sustainable Development Goals in Carbon Capture and Utilisation. Energy Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikunda, T.; Brunner, L.; Skylogianni, E.; Monteiro, J.; Rycroft, L.; Kemper, J. Carbon Capture and Storage and the Sustainable Development Goals. Int. J. Greenh. Gas. Control 2021, 108, 103318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashari, D.P.S.; Zagloel, T.Y.M.; Soesilo, T.E.B.; Maftuchah, I. A Bibliometric and Literature Review: Alignment of Green Finance and Carbon Trading. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Yu, W.; Zhou, Z. Global Trends of Carbon Finance: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podder, J.; Patra, B.R.; Pattnaik, F.; Nanda, S.; Dalai, A.K. A Review of Carbon Capture and Valorization Technologies. Energies 2023, 16, 2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fujita, T. A Review of Research on Embodied Carbon in International Trade. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.M. Trade-Based Carbon Sequestration Accounting. Environ. Manag. 2004, 33, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, D.; Gross, M. Stuck on Coal and Persuasion? A Critical Review of Carbon Capture and Storage Communication. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 82, 102306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marland, G.; Marland, E. Trading Permanent and Temporary Carbon Emissions Credits: An Editorial Comment. Clim. Chang. 2009, 95, 465–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitland, G.C. Carbon Capture and Storage: Concluding Remarks. Faraday Discuss. 2016, 192, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Xu, C. Mapping Research on Carbon Emissions Trading: A Co-Citation Analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 74, 1314–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, C.; Wu, C. One Step Upcycling CO2 from Flue Gas into CO Using Natural Stone in an Integrated CO2 Capture and Utilisation System. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2022, 5, 100078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, M.; Bui, M.; Adjiman, C.S.; Adjiman, C.S.; Stolten, D.; Bardow, A.; Bardow, A.; Anthony, E.J.; Anthony, E.J.; Boston, A.; et al. Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS): The Way Forward. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 1062–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; Lu, X.; Wang, D. A Systematic Review of Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage: Status, Progress and Challenges. Energies 2023, 16, 2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desport, L.; Selosse, S. An Overview of CO2 Capture and Utilization in Energy Models. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 180, 106150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Liang, S.; Wang, R.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Xie, B.; Toe, C.Y.; Zhu, X.; Wang, J.; et al. Industrial Carbon Dioxide Capture and Utilization: State of the Art and Future Challenges. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 8584–8686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochedi, F.O.; Yu, J.; Yu, H.; Liu, Y.; Hussain, A. Carbon Dioxide Capture Using Liquid Absorption Methods: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 77–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentener, F.; Stevenson, D.; Cofala, J.; Mechler, R.; Amann, M.; Bergamaschi, P.; Raes, F.; Derwent, R. The Impact of Air Pollutant and Methane Emission Controls on Tropospheric Ozone and Radiative Forcing: CTM Calculations for the Period 1990–2030. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2005, 5, 1731–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Huang, Q.; Xu, Z.; Sipra, A.T.; Gao, N.; de Souza Vandenberghe, L.P.; Vieira, S.; Soccol, C.R.; Zhao, R.; Deng, S. A Comprehensive Review of Carbon Capture Science and Technologies. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2024, 11, 100178. [Google Scholar]

- Iliyas, A.; Zahedi-Niaki, H.M.; Eić, M. One-Dimensional Molecular Sieves for Hydrocarbon Cold-Start Emission Control: Influence of Water and CO2. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2010, 382, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaraweera, S.M.; Gunathilake, C.A.; Gunawardene, O.H.P.; Dassanayake, R.S.; Cho, E.B.; Du, Y. Carbon Capture Using Porous Silica Materials. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, O.D.Q.F.; De Medeiros, J.L. Carbon Capture and Storage Technologies: Present Scenario and Drivers of Innovation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2017, 17, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, F.K.; Foo, D.C.Y.; Eljack, F.T.; Atilhan, M.; Chemmangattuvalappil, N.G. Ionic Liquid Design for Enhanced Carbon Dioxide Capture by Computer-Aided Molecular Design Approach. Clean. Techn Env. Policy 2015, 17, 1301–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, D.K.; Oduniyi, I.A.; Alex Sam, A. A Novel Cryogenic Technology for Low-Cost Carbon Capture from NGCC Power Plants for Climate Change Mitigation. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2022, 36, 101495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M.K.; Smetana, V.; Hiti, E.A.; Wineinger, H.B.; Qu, F.; Mudring, A.-V.; Rogers, R.D. CO2 Capture from Ambient Air via Crystallization with Tetraalkylammonium Hydroxides. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 17724–17732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, S.; Rodrigues De Souza, A.P.; Lobo Baeta, B.E. Technologies for Carbon Dioxide Capture: A Review Applied to Energy Sectors. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2022, 8, 100456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.J.; Edmonds, J.A.; Mahasenan, N.; Roop, J.M.; Brunello, A.L.; Haites, E.F. International Emission Trading and the Cost of Greenhouse Gas Emissions Mitigation and Sequestration. Clim. Chang. 2004, 64, 257–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevnaker, T.; Wettestad, J. Linked Carbon Markets: Silver Bullet, or Castle in the Air? Clim. Law 2016, 6, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doda, B.; Taschini, L. Carbon Dating: When Is It Beneficial to Link ETSs? J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2017, 4, 701–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Shrestha, A.K.; Wang, G.; Innes, J.L.; Wang, K.X.; Li, N.; Li, J.; He, Y.; Sheng, C.; Niles, J.-O. A Linkage Framework for the China National Emission Trading System (CETS): Insight from Key Global Carbon Markets. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Li, C.; Yao, Y.; Lai, W.; Tang, J.; Shao, C.; Zhang, Q. Bi-Level Carbon Trading Model on Demand Side for Integrated Electricity-Gas System. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2023, 14, 2681–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gola, S.; Noussia, K. From CO2 Sources to Sinks: Regulatory Challenges for Trans-Boundary Trade, Shipment and Storage. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 179, 106039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jin, C.; Yin, M.; An, Q. Rapid Fabrication of High-Permeability Mixed Matrix Membranes at Mild Condition for CO2 Capture (Small 19/2023). Small 2023, 19, 2370133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Peng, L.; Moitra, D.; Liu, H.; Fu, Y.; Dong, Z.; Hu, W.; Lei, M.; Jiang, D.; Lin, H.; et al. Harnessing the Hybridization of a Metal-Organic Framework and Superbase-Derived Ionic Liquid for High-Performance Direct Air Capture of CO2. Small 2023, 19, 2302708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanos, G.E.; Schulz, P.S.; Bahlmann, M.; Wasserscheid, P.; Sapalidis, A.; Katsaros, F.K.; Athanasekou, C.P.; Beltsios, K.; Kanellopoulos, N.K. CO2 Capture by Novel Supported Ionic Liquid Phase Systems Consisting of Silica Nanoparticles Encapsulating Amine-Functionalized Ionic Liquids. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 24437–24451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Kim, J.; Gurr, P.A.; Scofield, J.M.P.; Kentish, S.E.; Qiao, G.G. A Novel Cross-Linked Nano-Coating for Carbon Dioxide Capture. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, A.; Krishnamoorti, R. Analysis of Direct Air Capture Integrated with Wind Energy and Enhanced Oil Recovery. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 2084–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.H.; Bang, J.; Park, G.; Choe, S.; Jang, Y.J.; Jang, H.W.; Kim, S.Y.; Ahn, S.H. Recent Advances in Electrochemical, Photochemical, and Photoelectrochemical Reduction of CO2 to C2+ Products. Small 2023, 19, 2205765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y. Preface: Special Topic on Photocatalytic or Electrocatalytic Reduction of CO2. Sci. China Chem. 2020, 63, 1703–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babacan, O.; De Causmaecker, S.; Gambhir, A.; Fajardy, M.; Rutherford, A.W.; Fantuzzi, A.; Nelson, J. Assessing the Feasibility of Carbon Dioxide Mitigation Options in Terms of Energy Usage. Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaramoorthy, S.; Kamath, D.; Nimbalkar, S.; Price, C.; Wenning, T.; Cresko, J. Energy Efficiency as a Foundational Technology Pillar for Industrial Decarbonization. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Fan, Q.; Xia, R.; Meyer, T.J. CO2 Reduction: From Homogeneous to Heterogeneous Electrocatalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, A.J.; Wilson, E.J. Deploying Carbon Capture and Storage in Europe and the United States: A Comparative Analysis. J. Eur. Env. Plan. Law 2007, 4, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viebahn, P.; Vallentin, D.; Höller, S.; Fischedick, M. Integrated Assessment of CCS in the German Power Plant Sector with Special Emphasis on the Competition with Renewable Energy Technologies. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2012, 17, 707–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.-M.; Kang, J.-N.; Liu, L.-C.; Li, Q.; Wang, P.-T.; Hou, J.-J.; Liang, Q.-M.; Liao, H.; Huang, S.-F.; Yu, B. A Proposed Global Layout of Carbon Capture and Storage in Line with a 2 °C Climate Target. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2021, 11, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aune, F.R.; Gaure, S.; Golombek, R.; Greaker, M.; Kittelsen, S.A.C.; Ma, L. Promoting CCS in Europe: A Case for Green Strategic Trade Policy? Energy J. 2022, 43, 71–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitmann, N.; Bertram, C.; Narita, D. Embedding CCS Infrastructure into the European Electricity System: A Policy Coordination Problem. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2012, 17, 669–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broecks, K.; Jack, C.; Ter Mors, E.; Boomsma, C.; Shackley, S. How Do People Perceive Carbon Capture and Storage for Industrial Processes? Examining Factors Underlying Public Opinion in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 81, 102236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Regulations for Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage: Comparative Analysis of Development in Europe, China and the Middle East. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 173, 105722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchino, M.; Popielak, P.; Panowski, M.; Wawrzyńczak, D.; Majchrzak-Kucęba, I.; De Falco, M. The Environmental Impacts of Carbon Capture Utilization and Storage on the Electricity Sector: A Life Cycle Assessment Comparison between Italy and Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 6809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Cai, S.; Ye, W.; Gu, A. Linking Emissions Trading Schemes: Economic Valuation of a Joint China–Japan–Korea Carbon Market. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, M. The New (Fragmented) Geography of Carbon Market Mechanisms: Governance Challenges from Thailand and Vietnam. Glob. Environ. Politics 2017, 17, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strefler, J.; Bauer, N.; Humpenöder, F.; Klein, D.; Popp, A.; Kriegler, E. Carbon Dioxide Removal Technologies Are Not Born Equal. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 074021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.R.T.L.; Siraj, S.; Ghazali, Z. An ISM Approach for Managing Critical Stakeholder Issues Regarding Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) Deployment in Developing Asian Countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izikowitz, D.; Li, J.; Wang, E.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, Y.W. Assessing Capacity to Deploy Direct Air Capture Technology at the Country Level—An Expert and Information Entropy Comparative Analysis. Environ. Res. Commun. 2023, 5, 045003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollak, M.; Phillips, S.J.; Vajjhala, S. Carbon Capture and Storage Policy in the United States: A New Coalition Endeavors to Change Existing Policy. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.-H.; Yang, J. An Assessment of Technological Innovation Capabilities of Carbon Capture and Storage Technology Based on Patent Analysis: A Comparative Study between China and the United States. Sustainability 2018, 10, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.-H.; Lyon, T.P. Promoting Global CCS RDD&D by Stronger U.S.–China Collaboration. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 6746–6769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kintisch, E.U.S. Carbon Plan Relies on Uncertain Capture Technology. Science 2013, 341, 1438–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.J.; Morgan, M.G.; Apt, J.; Bonner, M.; Bunting, C.; Gode, J.; Haszeldine, R.S.; Jaeger, C.C.; Keith, D.W.; McCoy, S.T.; et al. Regulating the Geological Sequestration of CO2. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 2718–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ding, X.; Song, X.; Dong, T.; Zhao, A.; Tan, M. Research on the Spillover Effect of China’s Carbon Market from the Perspective of Regional Cooperation. Energies 2023, 16, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Zheng, J.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, Y. Provincial Carbon Emission Quota Allocation Study in China from the Perspective of Abatement Cost and Regional Cooperation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendi, M.; Bui, M.; Mac Dowell, N.; Fennell, P. Geospatial Analysis of Regional Climate Impacts to Accelerate Cost-Efficient Direct Air Capture Deployment. One Earth 2022, 5, 1153–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Cui, G.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Dai, S.; Wang, J. Reply to the Correspondence on “Preorganization and Cooperation for Highly Efficient and Reversible Capture of Low-Concentration CO2 by Ionic Liquids”. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanatta, M.; Simon, N.M.; dos Santos, F.P.; Corvo, M.C.; Cabrita, E.J.; Dupont, J. Correspondence on “Preorganization and Cooperation for Highly Efficient and Reversible Capture of Low-Concentration CO2 by Ionic Liquids”. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.E.; Tomski, P. The Sustainability Workforce Shift: Building a Talent Pipeline and Career Network. Matter 2023, 6, 2471–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Research Content |

|---|---|

| Total Literature | 40,600 |

| Search Keywords | Carbon Trading, Carbon Capture |

| Database | Google Scholar, Web of Science, Scopus |

| Research Period | Multiple research periods (e.g., 2014–2022, 1992–2021) |

| Main Research Summary | The important role of carbon trading and carbon capture technologies in mitigating climate change |

| Mashari et al. [8] | Analyzed 506 articles on sustainable finance and carbon trading from 2014–2022, highlighting the need for further research connecting these two fields effectively. |

| Su and Yu [9] | Analyzed 4408 scholarly articles on carbon finance from 1992–2021, noting rapid publication growth and interest in carbon capture, economic growth, and carbon price forecasting. |

| Podder et al. [10] | Provided a comprehensive overview of carbon emissions from fossil fuel consumption and the importance of Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), detailing mechanisms such as pre-combustion, post-combustion, and direct air capture. |

| Fujita [11] | Reviewed 626 articles on embodied carbon emissions and international pollution identification methods from 1994–2023, discussing the role of carbon trading in controlling emissions. |

| Kim [12] | Discussed accounting methods for early carbon sequestration investments and trades, emphasizing the need for standardized credit rating to ensure the integrity of carbon sequestration credit trading. |

| Otto and Gross [13] | Systematically reviewed 115 articles on communication practices regarding Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), underlining the importance of effective stakeholder engagement. |

| Altman [3] | Discussed the extensive debate and research on incorporating carbon capture and storage technologies under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) of the Kyoto Protocol. (The Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) is an important component of the Kyoto Protocol aimed at promoting emission reductions while encouraging sustainable development in developing countries. It allows developed countries (Annex I countries) to fund projects in developing countries (non-Annex I countries) and receive Certified Emission Reductions (CERs) to meet their emission reduction commitments.) |

| Malan and Malan [14] | Analyzed challenges in comparing emission reductions and carbon sequestration, particularly issues related to the duration of storage for captured carbon dioxide. |

| Maitland [15] | Discussed carbon capture and storage technologies, emphasizing the need for tighter integration of materials and process design to optimize carbon dioxide capture and utilization processes. |

| Yu and Xu [16] | Scientometric analysis of Carbon Emission Trading (CET), highlighting the growth in publication numbers in the field and its major research areas, providing a clear picture of the current state and future trends. (Carbon Emission Trading (CET) is a market-oriented approach to reducing emissions by setting an emission cap and allowing entities to buy and sell allowances to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. This system is designed to incentivize businesses to reduce emissions cost-effectively while promoting sustainable development.) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, F.-H.; Liu, H.-R. Analyze the Temporal and Spatial Distribution of Carbon Capture in Sustainable Development of Work. Energies 2024, 17, 5416. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17215416

Chen F-H, Liu H-R. Analyze the Temporal and Spatial Distribution of Carbon Capture in Sustainable Development of Work. Energies. 2024; 17(21):5416. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17215416

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Fu-Hsuan, and Hao-Ren Liu. 2024. "Analyze the Temporal and Spatial Distribution of Carbon Capture in Sustainable Development of Work" Energies 17, no. 21: 5416. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17215416

APA StyleChen, F.-H., & Liu, H.-R. (2024). Analyze the Temporal and Spatial Distribution of Carbon Capture in Sustainable Development of Work. Energies, 17(21), 5416. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17215416