Abstract

The aim of this article is to examine which selected internal factors influence the profitability (ROA) of companies in the energy sector in Poland and how they do so, over the period 2018–2021, taking into account two groups: all types of activities (984 companies) and electricity production (508 companies). This study uses Pearson correlation analysis, Wilcoxon pairwise rank test, descriptive statistics and multiple linear regression to build eight ROA econometric models, four for each group. The research shows that in the energy sector, in particular, variables relating to the capital structure (total equity/total assets, long-term liabilities/total assets, short-term liabilities/total assets and long-term liabilities/short-term liabilities ratios) have a statistically significant impact (positive or negative) on the profitability (ROA). The aforementioned ratios appear in various combinations in all eight ROA models. The use of equity to finance the activities of companies in this sector seems to be particularly beneficial, as the total equity/total assets ratio occurs in as many as seven out of eight models and, moreover, it always has a positive impact on the ROA. The remaining analyzed variables relating to the structure of assets (fixed assets/total assets ratio), financial liquidity (current ratio) and the age of the company appear in the models as statistically significant quite rarely, having a different impact on the ROA (positively or negatively). However, variables such as the fixed assets/current assets and total liabilities/total equity ratios do not have a statistically significant impact on the ROA at all in any of the studied groups of enterprises. The research results suggest that managers, in order to shape profitability (measured by ROA), should pay special attention to the capital structure, i.e., the proportions of the use of equity, long-term liabilities and short-term liabilities to finance the operations of energy companies as these independent variables appear most often in ROA models. Other analyzed factors, such as the assets structure (the share of fixed assets in total assets) or financial liquidity, also have an impact on the return on assets; therefore, their use in energy companies should also be considered. Moreover, the research shows a large diversity of factors shaping ROA in econometric models, the way they affect the dependent variable (positive or negative) and the degree of model fit (R2), both in individual years and in the two groups of companies studied. This proves that it is not possible to clearly and finally determine which factors and how (positive or negative) they affect the profitability. This influence can change over time depending on the circumstances, which indicates the need for the continuous involvement of decision makers in the management process and making decisions based on reliable and appropriate-to-the-situation analyses.

1. Introduction

Profitability is immensely important because it reflects the company’s ability to generate profit, as well as the efficiency of using its resources [1]. Without positive profitability, a company is unable to survive and develop in the long term [2]. For this reason, not only the owners of the company are interested in the level of profitability, but also other stakeholders, including investors, lenders, suppliers, customers and employees. The higher the profits and profitability, the better the company, its ability to develop and its managers are assessed [3,4], regardless of the industry in which it operates.

A profitability assessment is possible by using various measures, e.g., profitability ratios. Profitability ratios constitute a relative measure; they allow one to assess the degree of business efficiency from various points of view, including resource utilization [5]. Among the commonly known and used, both in theory and practice, financial profitability indicators based on profit include a return on equity (ROE) and return on assets (ROA). ROE allows one to assess profitability in relation to shareholders’ equity. ROA, on the other hand, reflects the efficiency of using all company resources (assets) and this is one of the reasons why it is considered to be one of the best measures of financial efficiency [6].

Due to the great importance of profitability for enterprises, over the last several dozen years, this topic has been repeatedly discussed in scientific research, and various factors influencing it have been analyzed in various industries. However, so far, research in this area has not been frequently conducted in the energy sector (especially in Poland), despite its great importance. Currently, energy is the basis for the functioning and development of almost every sector of the economy. Energy supplies, consumption and prices translate, among others, into the profitability and productivity of business entities in all industries [7]. The energy sector has an impact on economic growth [8], industrial development and household needs [9], just to name a few.

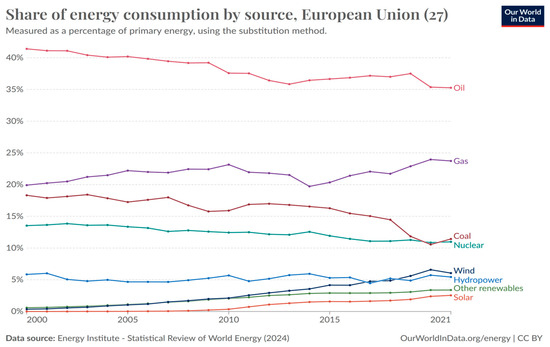

Poland is struggling with a huge transformation challenge in the energy–climate area. This is partly related to the implementation of solutions resulting from European Union regulations aimed at limiting the degradation of the natural environment. Currently, one of the goals of the European Union’s development strategy, called the European Green Deal, assumes that by 2050, Europe will become the first climate-neutral continent [10]. Achieving this ambitious goal will involve the almost complete elimination of greenhouse gas emissions, which will not be possible without giving up fossil fuels, i.e., coal, oil and gas [11], and comprehensive changes in the economies of member states. Figure 1 shows the energy consumption by source in the EU in 2000–2021.

Figure 1.

Share of energy consumption by source in European Union (27) in 2000–2021. Source: Our World in Data [12].

As shown in Figure 1, the energy consumption from fossil fuels dominates in the EU—over 70% (oil 35.26%, gas 23.73% and coal 11.43%)—and a significant share in the energy mix is nuclear energy (10.98%) and renewable energy (17.4%) [12].

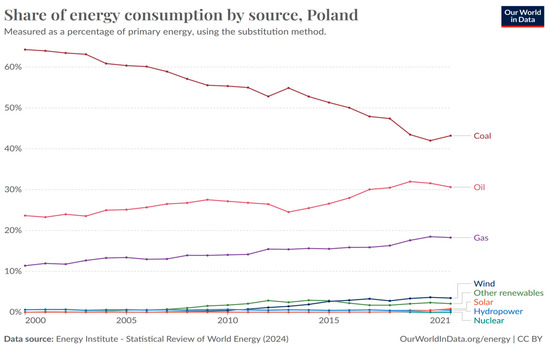

For Poland, achieving low emission will be particularly difficult because, for now, it has an energy-intensive economy structure and the share of fossil fuels (especially coal) in the energy mix is very large [11], which is mainly determined by the natural resources it has [13].

The energy consumption by source in 2000–2021 in Poland is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Share of energy consumption by source in Poland in 2000–2021. Source: Our World in Data [12].

Despite noticeable changes in the structure of energy consumption by sources in Poland over the period 2000–2021, in 2021, fossil fuels still dominated, with coal at the forefront—in total, approximately 92.10% (coal 43.20%, oil 30.63% and gas 18.27%) and energy from renewable sources constituted approximately 6.91% [12].

The largest energy consumers in Poland both in 2000 and 2021 were three sectors: industry, transport and residential (Table 1).

Table 1.

Poland—final energy consumption by sector (normal climate) in years 2000 and 2021.

According to the Statistics Poland, in 2021, households used the most energy for space heating (65.4%) and water (17.1%), cooking (8.3%), joint lighting and electrical appliances (9.2%) and a similar structure has been maintained for years [13]. The energy used by Polish households comes mainly from burning coal [15,16].

When it comes to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in Poland, in 2021, the first place was taken by energy production (46%), the second place was taken by transport (17%), then industry at 14%, buildings (11%), agriculture (11%) and waste management (1%) [17].

Building a zero-emission economy in Poland will, therefore, require a deep transformation in many areas, especially in the energy sector. The costs of this transformation will also be enormous. According to Institut Rousseau [17] estimates, zero-emission investments will cost Poland EUR 2.4 trillion by 2050, with an annual average of EUR 90 billion, which is approximately 13.6% of the current GDP. In turn, the costs of achieving zero emissions in the EU will be EUR 40 trillion by 2050, with an annual average of EUR 1520 billion, which is approximately 10% of the current of EU-27 GDP [18]. It is assumed that the investment will be financed partly from EU funds, national public funds and private funds [19]. In the context of the challenges facing the Polish energy sector, the condition of enterprises operating in it, reflected, among others, in the profitability, skilful management and use of available resources, will be of great importance not only for them, but also for the entire economy.

In light of the literature review and the presented challenges, the aim of this article is to examine which selected internal factors influence the profitability (ROA) of companies in the energy sector in Poland and how they do so, over the period 2018–2021, taking into account two groups: all types of activities (984 companies) and electricity production (508 companies). The research conducted in this article provides answers to the following questions:

- Do all analyzed internal factors have a statistically significant impact on profitability (ROA)?

- Is the impact of analyzed statistically significant internal factors on profitability (ROA) the same in the individual years covered by the study and in both groups of companies?

In this context, two research hypotheses are formulated:

Hypothesis H1:

Not all analyzed internal factors have a statistically significant impact on profitability (ROA).

Hypothesis H2:

Statistically significant internal factors have a varied impact on profitability (ROA) in the individual years covered by the study and in both groups of companies.

This article fits into the research gap and the research results will contribute not only to the literature on the subject by expanding the scope of existing knowledge in the area of factors shaping the profitability of companies from the energy sector in the example of Poland, but may also constitute a valuable guideline for managers in this area.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Factors Affecting the Company’s Profitability

The importance of profitability for the survival and development of companies causes both scientists and practitioners to look for factors that have a significant impact on it. The identification of these factors would allow for conscious management and increase the chances of the company’s long-term success on the market.

Factors affecting the profitability of a company can be classified according to various criteria. One possibility is to divide them into external factors resulting from the company’s external environment and internal factors derived from the company [20]. Another more detailed classification allows one to distinguish [21] global determinants (e.g., global business cycles and trends in world market inputs/outputs), country determinants (e.g., the education system, fiscal policy and GDP), industry determinants (e.g., entry barriers, technology and competitors) and company determinants (e.g., profits and financial leverage).

Companies generally have no influence on the external determinants of profitability, but knowing them enables one, to a greater or lesser extent, to prepare for their occurrence. In turn, internal factors can be actively shaped by companies.

The review of the conducted scientific research shows a large diversity of research samples (in terms of the number, industries and countries), research periods, analyzed factors shaping profitability and their measures, research methods used and the results obtained. This diversity, on the one hand, proves the high importance and complexity of the research problem and, on the other hand, it may cause difficulties in the interpretation of the results, and especially in their comparability. Examples of analyzed variables affecting the profitability of enterprises, their measures and research samples used by various researchers are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Examples of variables influencing the profitability of enterprises, their measures and research samples.

Due to the breadth of the topic, the subsequent part of the literature review will discuss the impact on profitability of only these internal factors that are taken into account in this study.

2.2. Capital Structure and Profitability

The capital structure reflects the combination of different sources of capital (equity and debt) [32] used to finance assets [33] or the company’s activities [34,35]. The shape of the capital structure can affect the profitability in several ways, including:

- Through tax benefits when interest on debt reduces the income tax burden, thereby increasing net profit [34,36,37];

- A too-high level of debt may be associated with an increased risk of insolvency or even bankruptcy, leading to associated costs, e.g., higher interest rates [38,39,40], court proceedings, loss of good reputation, market position and, consequently, customers, suppliers and employees [41];

- Engaging debt may lead to a conflict of interests between individual stakeholders of the company, such as owners, managers and lenders (the so-called agency conflict) and the creation of agency costs [34,42,43].

Based on research of 272 American firms (service and manufacturing) listed on the New York Stock Exchange for the period of 2005–2007, Gill, Biger and Mathur (2011) [34] established a positive relationship between debt and profitability, although the results differ slightly between the groups. In manufacturing enterprises, there is a positive relationship between profitability and short-term debt, long-term debt and total debt to asset ratios. In service enterprises, a positive relationship is found between profitability and short-term and total debt to asset ratios, while long-term debt does not show a significant relationship with profitability.

Shubita and Alsawalhah (2012) [44] analyze the relationship between the capital structure and profitability of 39 Jordanian industrial companies on the Amman Stock Exchange in the years 2004–2009. The research results show a significant negative impact of debt (measured by the following indicators: short-term debt/total assets, long-term debt/total assets and total debt/total assets) on the return on equity (net income/average equity), which proves that the greater the debt, the lower the profitability. Based on the research results, the authors suggest that companies should look for the most favorable debt-to-equity ratio, which can minimize capital costs and reduce the risk of bankruptcy. Similar results are obtained by Hamid, Abdullah and Kamaruzzaman (2015) [45]. The research sample includes 92 firms (46 family firms and 46 non-family firms) in Malaysia during a period of 2009 to 2011. They establish a negative relationship between debt ratios (short-term debt ratio, long-term debt ratio and total debt ratio) and profitability measured by the return on equity in both groups of companies.

Salim and Yadav (2012) [46] study the relationship between the capital structure and performance of 237 Malaysian companies from the Bursa Malaysia Stock Exchange in 1995–2011. The research sample includes companies from as many as six sectors: construction, consumer products, industrial products, plantation, property, trading and services. The capital structure is measured, among others, by long-term debt, short-term debt and total debt ratios and performance is measured by the return on equity, return on assets, Tobin s Q and earnings per share. Overall, the results show that short-term debt, long-term debt and total debt have a negative relationship with performance, measured by ROA, ROE and earnings per share. Tobin’s Q has a significantly positive relationship with short-term debt and long-term debt, but a significantly negative relationship with total debt. The results of detailed analyses conducted for individual sectors differ.

2.3. Fixed Assets and Profitability

The asset structure reflects the share of individual types of assets in total assets [47]. Companies with a large share of fixed assets in total assets may have lower profitability due to incurring high costs of capital from debt [48].

Tariq Bhutta and Hasan (2013) [49] found a negative, but statically insignificant relationship between the tangibility of assets (calculated as a ratio of fixed assets divided by total assets) and profitability measured by ROS (the ratio of net income after taxes divided by total sales) in 12 companies listed in the food sector of the Karachi stock market in Pakistan, in the period of 2002–2006. Research by Putra, Sari and Astuty (2021) [48] shows that the asset structure negatively affects the profitability (ROA) of the manufacturing companies (71 companies, period 2015–2019) listed in the Indonesia Stock Exchange in a significant way. The negative relationship between the share of fixed assets in the total assets and profitability (ROA) is also confirmed by Burja’s research (2011) [50].

Abbas, Bashir, Manzoor and Akram (2013) [51] study the determinants affecting the company’s financial performance in the textile sector of Pakistan for the period 2005–2010. The sample covers 139 companies (non-financial) listed in the Karachi Stock Exchange. Their research reveals that tangibility is not important in achieving the company’s performance (measured by ROI calculated as EBIT/total assets) in the textile sector of Pakistan. The research by Rađo and Peštović (2022) [24] of companies from the manufacturing sector in the Republic of Serbia during 2017–2020 also reveals that the asset structure (fixed assets ratio) does not affect the profitability measured by ROA and ROE.

However, there are also studies by Agegnew and Gujral (2022) [2] confirming a statistically significant positive impact of tangibility on profitability (ROA) in manufacturing companies (10 companies, period 2012–2021) operating in Hawassa, Ethiopia. A positive relationship between the share of fixed assets in total assets and profitability (ROA and ROE) is also determined by Sah and Magar (2021) [29] in Nepalese insurance companies (21 insurance companies, period 2011/12–2018/19).

2.4. Financial Liquidity and Profitability

Financial liquidity can be interpreted as the ability of an enterprise to settle its long- and short-term liabilities on time [52,53,54,55]. It is related to the ease with which a company’s assets can be converted into cash, without losing their value and at the lowest possible transaction costs [52,53]. Financial liquidity affects effective operation, investment opportunities and limits unfavorable market changes [40].

Research conducted by Nguyen and Nguyen (2020) [56] on a sample of 1343 Vietnamese companies listed in the Vietnamese Stock Exchange of six different industries, in the period 2014–2017, reveals a positive relationship between financial liquidity (short-term assets/short-term liability) and financial performance measured by ROA and ROE, but negative by ROS. Also, Latif, Isa, Zaharum and Baharudin (2022) [27] discover that there is a significant positive relationship between profitability (ROA) and liquidity (current ratio calculated as current assets/current liabilities) on the basis of 20 Malaysian technology companies listed on the ACE Market of Bursa Malaysia in the period of 2016–2020.

Okpiabhele and Tafamel (2020) [57] conducted research on the relationship between financial liquidity measured by three indicators (the current ratio, quick ratio and growth ratio) and profitability (ROA) in 28 companies of consumer and industrial goods listed on the Nigerian Stock Exchange in a period of 2009–2018. They find that the current ratio has an insignificant negative impact on ROA, while the quick ratio and growth ratio have a significant positive impact on ROA.

However, there are also studies that show a negative relationship between financial liquidity and profitability. Research conducted by Majerowska and Gostkowska-Drzewicka (2018) [58] on a sample of 477 companies from various sectors listed on the Warsaw Stock Exchange in 1998–2016 reveals a negative relationship between financial liquidity (measured by the relation of current assets to current liabilities) and profitability (ROA and ROE).

2.5. Company Age and Profitability

On the one hand, companies operating on the market longer, through greater experience and learning, can operate more effectively and achieve better results [25]. Moreover, older companies, thanks to their experience, compatibility and reputation, may also have better access to financing [59]. On the other hand, older companies may be more bureaucratic, less flexible, and slower to adapt to market changes [25].

Research by Zhao, Pei and Pan (2021) [60] of 53 Chinese insurance companies in 2013–2017 proves that age has a significantly negative impact on profitability (measured by profit ratio efficiency). Also, the results of research by Blažková and Dvouletý (2018) [61] on 622 companies in 10 sectors of the Czech food processing industry, period 2005–2012, reveal a negative relationship between the age of companies and profitability measured by ROA.

In turn, research of 440 public and private firms in the hospitality sector in India in the years 2010–2020, conducted by Soni, Arora and Le (2023) [26], shows that age has a significant positive impact on profitability (ROA). Pervan, Pervan and Ćurak (2019) [62], examining 9359 firms in the manufacturing industry in Croatia, in the period 2006–2015, found that there is a positive relationship between the firm’s age and profitability (ROA). Similar results were also obtained by Sahabuddin and Khan Synthia (2020) [59].

3. Materials and Methods

This research aims to check which selected internal factors (independent variables) influence the profitability (dependent variables measured by ROA) of companies from the energy sector in Poland. The time scope of the study is a period of 4 years, from 2018 to 2021. The research is carried out on an annual basis to determine whether the impact of independent variables on profitability is constant in particular years, or whether it changes. Moreover, the research is conducted separately for two groups, i.e.,

- For all companies, regardless of the type of business (984 companies);

- For companies dealing only with electricity production (508 companies).

The study of two groups of companies results from the desire to determine whether the analyzed internal factors have the same impact on profitability (ROA), regardless of the type of business activity. In turn, the separation of electricity production companies as a second group results from their large number (508 companies), which may affect the greater reliability of the results obtained.

Pearson correlation analysis, Wilcoxon pairwise rank test, descriptive statistics and multiple linear regression are used in the research. The research is conducted at the significance level α = 0.05.

3.1. Research Sample

Data about companies come from the EMIS database. Companies are selected based on their main area of activity classified in section D, Division 35. Production and supply of electricity, gas, steam, hot water and air for air conditioning systems, in accordance with the Polish Classification of Activities (PKD 2007). Initially, the database includes over 8000 energy companies (listed and non-listed in the Warsaw Stock Exchange). To ensure completeness and comparability, only those companies that were operating continuously over the period 2018–2021 and provide data enabling the calculation of the variables adopted for the research are included. For this reason, the final research sample covers 984 companies from the energy sector that deal with energy production, trade, transmission and distribution. In total, 508 companies dealing only with electricity production are separated from 984 companies. Moreover, all 984 companies are the same entities in each year that have been operating continuously for at least the 4 years covered by the study (2018–2021).

3.2. Research Model

The research is conducted in four stages.

Stage 1. At this stage, internal factors shaping the profitability are selected, which is ultimately determined by the availability and completeness of data. The set of independent variables is as follows:

- The age of the company (number of years since the company was founded);

- The fixed assets/total assets ratio;

- The fixed assets/current assets ratio;

- The total equity/total assets ratio;

- The long-term liabilities/total assets ratio;

- The short-term liabilities/total assets ratio;

- The total liabilities/total equity ratio;

- The long-term liabilities/short-term liabilities ratio;

- The current ratio (short-term assets/short-term liabilities ratio).

The dependent variable is profitability measured by ROA (net income/total assets ratio).

The values of all variables are calculated on the basis of data (downloaded from the EMIS database) from the individual financial statements.

Stage 2. In the second stage, the variables selected in stage 1 are verified using Pearson correlation analysis: the correlations between independent variables are checked (to eliminate those that are strongly related to each other), as well as those between independent variables and dependent variables (to choose those that are strongly related to dependent variable). Moreover, the coefficients of variation are checked. All analyses are performed for the research sample of 984 companies.

After conducting the research, it turns out that seven independent variables from the adopted set have a statistically significant impact on profitability (ROA), i.e.,

- The age of the company (X1);

- The total equity/total assets ratio (X2);

- The long-term liabilities/total assets ratio (X3);

- The short-term liabilities/total assets ratio (X4);

- The long-term liabilities/short-term liabilities ratio (X5);

- The fixed assets/total assets ratio (X6);

- The current ratio (X7).

Stage 3. Descriptive statistics (mean, median, minimum and maximum values, standard deviation, coefficient of variation, skewness and kurtosis) are performed for variables that turn out to be statistically significant. The Wilcoxon pairwise rank test is used to check the differences in indicators between the individual years of the study. All results are presented in figures and tables.

Stage 4. Based on the independent variables selected in stage 2, econometric models are built using multiple linear regression, separately for each year covered by the analysis and two groups of companies.

The multiple linear regression is chosen to build the econometric models, which results from the nature of the variables adopted for the study (quantitative variables). The multiple linear regression allows for checking the relationships that may appear between variables and for explaining the impact of each independent variable on the dependent variable, assuming that the other analyzed independent variables remain constant.

The general form of the econometric model in multiple linear regression for profitability (ROA) is as follows:

where:

—dependent variable (profitability measured by ROA);

—independent variables from 1 to 7;

—coefficient from 1 to 7;

—constant.

In the presentation of the ROA econometric models in individual years, only these independent variables that have a statistically significant impact on the dependent variable are taken into account.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.1.1. Profitability (ROA)

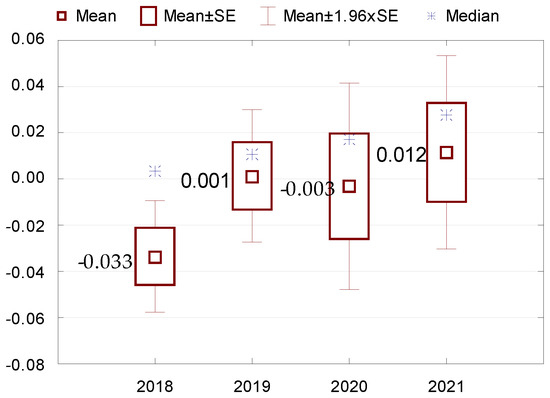

ROA (net income/total assets ratio) is used as the dependent variable in the study. ROA informs how many units of profit (positive value) or loss (negative value) are generated by a unit of assets. The conducted research shows that the average ROA value is characterized by an upward trend (Figure 3, Table 3). The lowest occurs in 2018 (−0.033) and the highest in 2021 (0.012). Interestingly, in two of the four analyzed years, i.e., 2018 and 2020, the average ROA values are negative. However, the median shows that in each of the years analyzed, half of the companies have an asset return of at least 0.003 (value from 2018). The greatest variation (as indicated by the standard deviation) takes place in 2020 (σ = 0.716). The asymmetry in each of the analyzed periods is left-sided, which means that the ROA indicator in most companies in the examined years is higher than average. However, the kurtosis informs about a significant concentration of ROA values around the average values in a given year.

Figure 3.

ROA in the surveyed companies in 2018–2021.

Table 3.

Basic descriptive statistics of ROA in the surveyed companies in 2018–2021.

It is checked whether there are statistically significant differences in the level of the ROA in individual years. The Wilcoxon pairwise rank test shows that there are differences in the years 2018/2019, 2019/2020 and 2020/2021 (p < α, p = 0.000).

4.1.2. Age of the Company (X1)

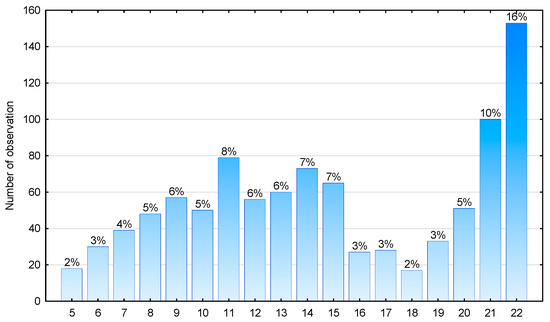

Age reflects the number of years since the company was founded, and is calculated for the last year of the study, i.e., 2021. The average length of time the surveyed companies have been operating on the market is almost 15 years (Table 4). The shortest period of time the surveyed companies have been operating on the market is 5 years and the longest period of operation is 22 years (Figure 4). The median activity is 14, which means that half of the surveyed companies have been on the market for 14 years or less and the other half for 14 years or longer. Most often, in the surveyed group of companies operating in the energy sector, there are companies with 22 years of operation—there are 153 such companies and they constitute 16% of the surveyed group. The coefficient of variation at the level of 36% indicates that the period of activity of companies on the market is quite varied, and the negative skewness indicates that most of the surveyed companies have been operating on the market for more than 15 years.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of the age of the surveyed companies.

Figure 4.

Percentage age distribution of the surveyed companies.

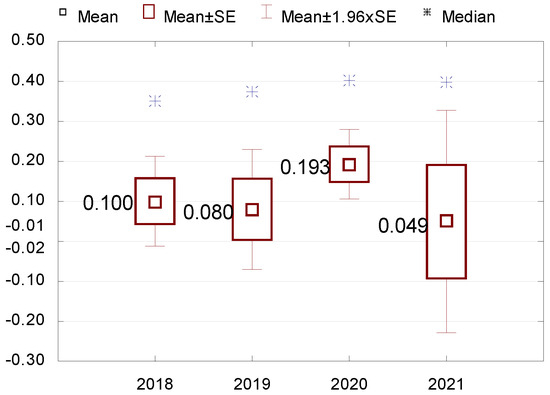

4.1.3. Total Equity/Total Assets Ratio (X2)

The total equity/total assets ratio reflects the extent to which a company’s assets are financed from equity. The lowest average value is recorded in 2019 ( = 0.08), while the highest average value of the indicator occurs in 2020 ( = 0.193) (Figure 5, Table 5). The median with values between 0.349 and 0.401 indicates that in each of the analyzed years, half of the companies finance their assets in at least approximately 35–40% from equity. By far the greatest variation in the total equity/total assets ratio value takes place in 2021, where the standard deviation is as much as 4.449. The asymmetry of the ratio distribution in each of the analyzed years is left-sided, which means that most companies have total equity/total assets ratios higher than the average. The kurtosis is positive and reaches high values, which indicates a high concentration of the total equity/total assets ratio around the average in each of the analyzed periods.

Figure 5.

Total equity/total assets ratio in the surveyed companies in 2018–2021.

Table 5.

Basic descriptive statistics of the total equity/total assets ratio in the surveyed companies in 2018–2021.

It is checked whether there are statistically significant differences in the level of the total equity/total assets ratio in individual years. The Wilcoxon pairwise rank test shows that there are differences in the years 2018/2019, 2019/2020, (p < α) but in the years 2020/2021, the differences are not statistically significant (p > α, p = 0.2255).

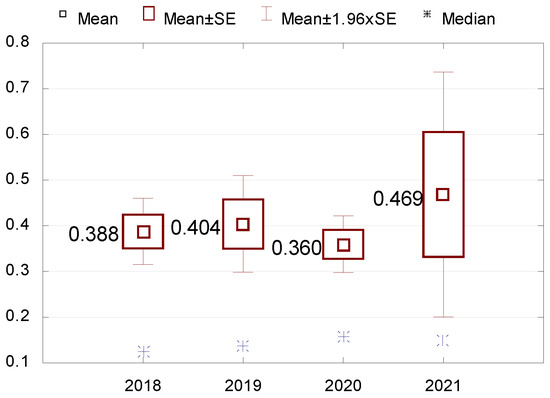

4.1.4. Long-Term Liabilities/Total Assets Ratio (X3)

The long-term liabilities/total assets ratio indicates the extent to which a company uses long-term liabilities to finance its activities. The analysis shows that half of the companies have approximately 12.5% or more long-term liabilities in their capital structure (median from 2018). The lowest average value of this indicator is recorded in 2020 ( = 0.360) and the highest value in 2021 ( = 0.469) (Figure 6, Table 6). By far, the greatest variation in the value of long-term liabilities/total assets takes place in 2021, where the standard deviation amounts to 4.291. The asymmetry of the ratio distribution in each of the years examined is right-sided, which means that most companies have long-term liabilities/total assets ratios lower than the average. The kurtosis is positive, which indicates a high concentration of the long-term liabilities/total assets ratio around the average value in each of the analyzed periods.

Figure 6.

Long-term liabilities/total assets ratio in the surveyed companies in 2018–2021.

Table 6.

Basic descriptive statistics of the long-term liabilities/total assets ratio in the surveyed companies in 2018–2021.

It is checked whether there are statistically significant differences in the level of the long-term liabilities/total assets ratio in individual years. The Wilcoxon pairwise rank test shows that there are differences in the years 2018/2019, 2019/2020 and 2020/2021 (p < α).

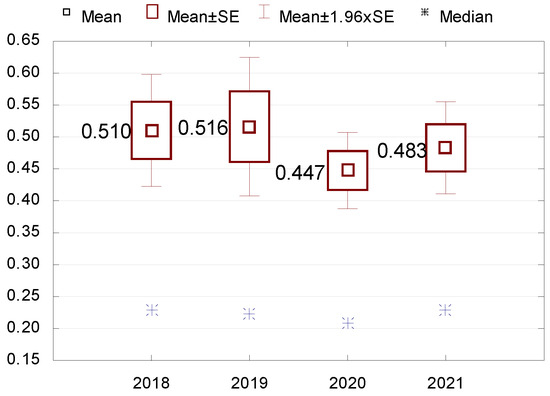

4.1.5. Short-Term Liabilities/Total Assets Ratio (X4)

The short-term liabilities/total assets ratio indicates the proportion in which short-term liabilities finance assets. The lowest average value is recorded in 2020 ( = 0.447), while the highest is in 2019 ( = 0.516) (Figure 7, Table 7). By far, the greatest variation in the value of the short-term liabilities/total assets ratio occurs in 2019, where the standard deviation is 1.753. The asymmetry of the ratio distribution in each of the years examined is right-sided, which means that most companies have short-term liabilities/total assets ratios lower than the average. The kurtosis is positive, which indicates a high concentration of the short-term liabilities/total assets ratio around the average value in each of the analyzed periods. Half of the companies engage approximately 20% or more of short-term liabilities in financing their operations each year (median from 2020).

Figure 7.

Short-term liabilities/total assets ratio in the surveyed companies in 2018–2021.

Table 7.

Basic descriptive statistics of the short-term liabilities/total assets ratio in the surveyed companies in 2018–2021.

It is checked whether there are statistically significant differences in the level of the short-term liabilities/total assets in individual years. The Wilcoxon pairwise rank test shows that there are no differences in the years 2018/2019 or 2019/2020, (p > α), but in the years 2020/2021, the differences are statistically significant (p < α, p = 0.000).

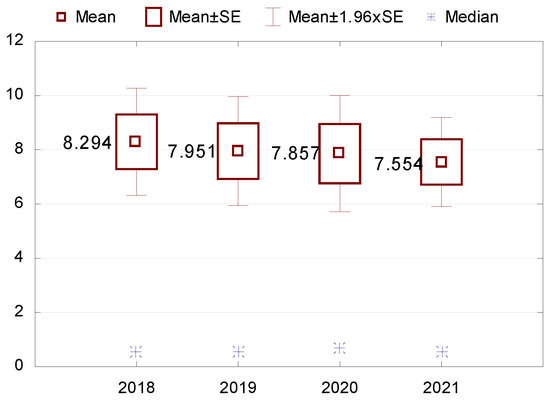

4.1.6. Long-Term Liabilities/Short-Term Liabilities Ratio (X5)

Another independent variable adopted for research is the long-term liabilities/short-term liabilities ratio. Over the analyzed years, there is a clear downward trend in the average value of the indicator (Figure 8, Table 8). The lowest average value is recorded in 2021 ( = 7.554), while the highest average value of the indicator occurs in 2018 ( = 8.294). The median with values between 0.524 and 0.661 in individual years indicates that in half of the enterprises long-term liabilities do not exceed 52.4% to 66.1% of short-term liabilities. The greatest variation in the value of long-term liabilities/short-term liabilities takes place in 2020, where the standard deviation amounts to 34.347. The asymmetry of the ratio distribution in each of the years examined is right-sided, which means that most companies have long-term liabilities/short-term liabilities ratios lower than the average. The kurtosis is positive, which indicates a high concentration of the value of the long-term liabilities/short-term liabilities ratio around the average value in each of the analyzed periods.

Figure 8.

Long-term liabilities/short-term liabilities ratio in the surveyed companies in 2018–2021.

Table 8.

Basic descriptive statistics of the long-term liabilities/short-term liabilities ratio in the surveyed companies in 2018–2021.

It is checked whether there are statistically significant differences in the level of the long-term liabilities/short-term liabilities in individual years. The Wilcoxon pairwise rank test shows that there are no differences in the years 2018/2019, (p > α, p = 0.5112) but in the years 2019/2020 and 2020/2021, the differences are statistically significant (p < α).

4.1.7. Fixed Assets/Total Assets Ratio (X6)

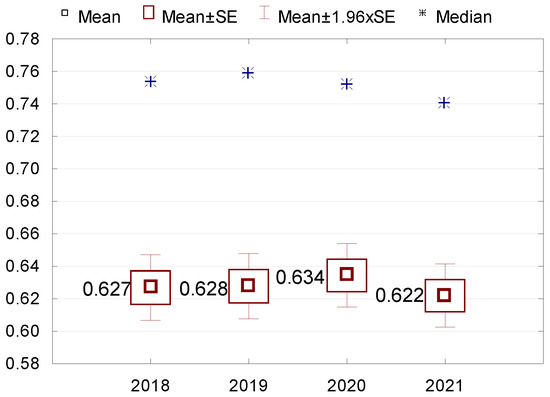

The degree of the long-term involvement of assets in the company’s operations is reflected in the fixed assets/total assets ratio. The average values of the indicator increase from 2018 (0.627) to 2020 (0.634), but in the last year of research, the indicator decreased again to 0.622 (Figure 9, Table 9). The variation of the indicator in companies is quite similar and ranges from 0.311 to 0.324, as indicated by the standard deviation, and the coefficient of variation is also similar, around 50%. The asymmetry of the ratio distribution in each of the analyzed years is left-sided, which means that most companies have fixed assets/total assets ratios higher than the average. The kurtosis is negative, which indicates the dispersion of indicators relative to the average value in each of the analyzed periods. The median of 0.740 or higher in all analyzed years proves that in half of the companies, approximately 75% or more of assets are fixed assets that are involved in operations for over a year.

Figure 9.

Fixed assets/total assets ratio in the surveyed companies in 2018–2021.

Table 9.

Basic descriptive statistics of the fixed assets/total assets ratio in the surveyed companies in 2018–2021.

It is checked whether there are statistically significant differences in the level of the fixed assets/total assets in individual years. The Wilcoxon pairwise rank test shows that there are differences in the years 2018/2019, 2019/2020 and 2020/2021 (p < α).

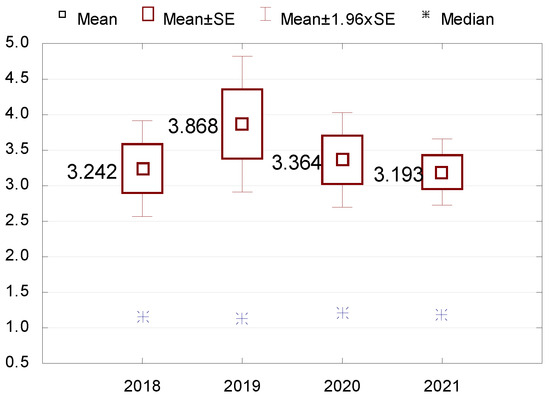

4.1.8. Current Ratio (X7)

Liquidity, i.e., the ability to pay liabilities, is reflected by the current ratio, calculated as short-term assets/short-term liabilities. In the literature on the subject, its preferred level can be found, which is above 1 [52] or around 1.2–2 [63], but it should be treated only as an indicative value, as it can significantly differ in individual sectors. The lowest average value is recorded in 2021 ( = 3.193), while the highest average value of the indicator occurs in 2019 ( = 3.868) (Figure 10, Table 10). By far, the greatest variation in the value of the current ratio also takes place in 2019, where the standard deviation amounts to 15.291. The asymmetry of the ratio distribution in each of the examined years is right-sided, which means that most companies have a current ratio lower than the average. The kurtosis is positive, which indicates a high concentration of the indicator values around the average value in each of the analyzed periods. However, in all analyzed years, the median of the current ratio reaches values above 1, so half of the companies from the energy sector should not have any problems with financial liquidity because their short-term assets are greater than short-term liabilities.

Figure 10.

Current ratio in the surveyed companies in 2018–2021.

Table 10.

Basic descriptive statistics of the current ratio in the surveyed companies in 2018–2021.

It is checked whether there are statistically significant differences in the level of the current ratio in individual years. The Wilcoxon pairwise rank test shows that there are no differences in the years 2020/2021 (p > α, p = 0.2512), but in the years 2018/2019 and 2019/2020, the differences are statistically significant (p < α).

4.2. ROA Econometric Models

4.2.1. ROA Econometric Models for the Group of All Companies Operating in the Energy Sector (N = 984)

The research shows that the ROA indicator in 2021 is, from the statistical point of view, significantly influenced by two variables: the total equity/total assets and the age of the company. The results of the model construction are presented in Table 11.

Table 11.

Results of ROA model construction for companies operating in the energy sector (N = 984) in 2021.

The model fits the data in 63% (R2 = 0.63), which means that it explains approximately 63% of the observed variability. The form of the model is as follows:

(0.039) (0.003) (0.002)

If the total equity/total assets ratio increases by one unit, ROA increases by 0.119 (assuming that the other independent variables remain constant), while if the company’s age increases by one year, ROA decreases by 0.006 (assuming that the other independent variables remain constant).

In 2020, three independent variables have a statistically significant impact on ROA, and the results of the analysis are presented in Table 12.

Table 12.

Results of ROA model construction for companies operating in the energy sector (N = 984) in 2020.

The model fits the data in 24% (R2 = 0.24). The form of the model is as follows:

(0.024) (0.021) (0.030) (0.001)

If the total equity/total assets ratio increases by one unit, ROA increases by 0.164 (assuming that the other independent variables remain constant); if the long-term liabilities/total assets ratio increases by one unit, ROA decreases by 0.15 (assuming that the other independent variables remain constant); and if the long-term liabilities/short-term liabilities ratio increases by one unit, ROA increases by 0.001 (assuming that the other independent variables remain constant).

In 2019, only two variables again have a statistically significant impact on ROA (Table 13).

Table 13.

Results of ROA model construction for companies operating in the energy sector (N = 984) in 2019.

The model fits the data in 10% (R2 = 0.10). The form of the model is as follows:

(0.015) (0.008) (0.011)

If the total equity/total assets ratio increases by one unit, ROA increases by 0.044 (assuming that the other independent variables remain constant), and if the short-term liabilities/total assets ratio increases by one unit, ROA decreases by 0.027 (assuming that the other independent variables remain constant).

However, in 2018, as many as six independent variables have a statistically significant impact on ROA (Table 14).

Table 14.

Results of ROA model construction for companies operating in the energy sector (N = 984) in 2018.

The model fits the data in 14% (R2 = 0.14). The form of the model is as follows:

(0.479) (0.480) (0.038) (0.480) (0.480) (0.001) (0.000)

Among the analyzed variables shaping ROA in 2018, as many as four of them (X2, X3, X4 and X5) concern the capital structure, one (X6) assets structure and one (X7) financial liquidity. Five variables show a positive relationship with ROA, which means that as their values increase, ROA also increases. Only one variable (the long-term liabilities/short-term liabilities ratio) shows a negative relationship, so as its value increases, ROA decreases. Importantly, the impact of each independent variable on ROA should be interpreted separately and assume that the other independent variables in the model remain constant.

4.2.2. ROA Econometric Models for a Group of Electricity Production Companies (N = 508)

The conducted research shows that only one independent variable has a statistically significant impact on ROA in 2021, i.e., the long-term liabilities/total assets ratio. The results of the model construction are presented in Table 15.

Table 15.

Results of ROA model construction for electricity production companies (N = 508) in 2021.

The model fits the data in 79% (R2 = 0.79). The form of the model is as follows:

(0.017) (0.003)

If the long-term liabilities/total assets ratio increases by one unit, ROA decreases by 0.121 (assuming that the other independent variables remain constant).

In 2020, two independent variables had a statistically significant impact on ROA (Table 16).

Table 16.

Results of ROA model construction for electricity production companies (N = 508) in 2020.

The model fits the data in 34% (R2 = 0.34). The form of the model is as follows:

(0.043) (0.026) (0.054)

If the total equity/total assets ratio increases by one unit, ROA increases by 0.305 (assuming that the other independent variables remain constant), and if the short-term liabilities/total assets ratio increases by one unit, ROA decreases by 0.161 (assuming that the other independent variables remain constant).

Among the analyzed variables, in 2019, only one independent variable has a statistically significant impact on ROA (Table 17).

Table 17.

Results of ROA model construction for electricity production companies (N = 508) in 2019.

The model fits the data in 7% (R2 = 0.07). The form of the model is as follows:

(0.024) (0.008)

If the total equity/total assets ratio increases by one unit, ROA increases by 0.05 (assuming that the other independent variables remain constant).

In 2018, four indicators are added to the model describing ROA (Table 18).

Table 18.

Results of ROA model construction for electricity production companies (N = 508) in 2018.

The model fits the data in 16% (R2 = 0.16). The form of the model is as follows:

(0.760) (0.764) (0.059) (0.764) (0.765)

Among the statistically significant independent variables included in this model, as many as three of them concern capital structure (X2, X3 and X4) and one (X6) concerns asset structure, while all of them are positively correlated with ROA. Importantly, the impact of each independent variable on ROA should be interpreted separately and assume that the other independent variables in the model remain constant.

Table 19 presents a summary of the econometric analysis for the ROA in 2018–2021, taking into account two groups of surveyed companies. The most fitting models are for 2021 where the coefficients of determination (R2) are the highest, while the lowest fit is for 2019.

Table 19.

Summary of econometric analysis of ROA models in 2018–2021 *.

By analyzing the data contained in Table 19, it can be noticed that one independent variable is of particular importance in ROA modeling. This is the total equity/total assets ratio, which appears in seven out of eight models (four in the group of all-types-of-activities companies and three in the group of electricity production companies). Moreover, in all seven models, the total equity/total assets ratio (X2) has a positive impact on the ROA.

In half of the models (two for all-types-of-activities companies and two for electricity production companies), the impact of the long-term liabilities/total assets ratio (X3) on profitability can be seen. In 2018, the long-term liabilities/total assets ratio appears in the ROA models of both groups of surveyed companies and its correlation with profitability is positive. However, in the other two models, i.e., in 2020 for all energy sector companies and in 2021 for electricity production companies, its impact on ROA is negative.

The situation is similar with the short-term liabilities/total assets ratio (X4). In 2018, it occurs in the models of both groups of surveyed companies and has positive impact on ROA, while in 2019 in the model for all companies, and in 2020 in the model for electricity production companies its impact on ROA is negative.

The long-term/short-term liabilities ratio (X5) appears only in two ROA models, only in the group of all energy sector companies, and its impact on profitability is negative in 2018 and positive in 2020.

The indicator related to the structure of assets, i.e., the fixed assets/total assets ratio (X6), appears only in 2018, but in the models of both analyzed groups, and its relationship with ROA is positive.

However, the current ratio (X7) occurs only in one model (in 2018), in the group of all energy sector companies, and its impact on ROA is positive.

The age of the company (X1) is also statistically significant only in one model in 2021 in the group of all energy sector companies, but its impact on ROA is negative.

Based on the results of the conducted research, it can be stated that both research hypotheses are positively verified.

The research shows that factors such as the fixed assets/current assets ratio and the total liabilities/total equity ratio not even once have a statistically significant impact on profitability (ROA) in any of the surveyed groups of enterprises. Therefore, the hypothesis H1, that not all analyzed internal factors have a statistically significant impact on profitability (ROA), is positively verified.

The research shows that factors such as the company age, the total equity/total assets ratio, the long-term liabilities/total assets ratio, the short-term liabilities/total assets ratio, the long-term liabilities/short-term liabilities ratio, the fixed assets/total assets ratio and the current ratio affect the dependent variable (ROA) in a different way (positive or negative) or not at all in the individual years covered by the analysis and in both groups of companies. On this basis, the hypothesis H2 is positively verified. Statistically significant internal factors have a varied impact on profitability (ROA) in the individual years covered by the study and in both groups of companies.

The relationship between similar firm-level variables and profitability in the energy sector is also analyzed by other researchers.

The research on a sample of 19,530 mining companies from 11 selected countries, 8 from Central and Eastern Europe and 3 from non-European countries, for the period of 2009–2017 was conducted by Škuláňová (2020) [64]. In her hypotheses, she assumes a negative relationship between total debt (total liabilities to equity ratio), long-term debt (long-term liabilities to equity ratio) and short-term debt (short-term liabilities to equity ratio) and profitability (ROA calculated as profit before tax and interest/total assets). Meanwhile, the research reveals varied results, e.g., for Polish companies, a negative relationship between the long-term and short-term debt ratio and profitability (ROA) is confirmed, while in Hungarian and Canadian companies, there is a positive relationship between the total debt and short-term debt ratio and profitability (ROA).

Research conducted by Wieczorek-Kosmala, Błach and Gorzeń-Mitka (2021) [65] on non-listed energy companies from central European countries, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia and the Czech Republic, in the period 2015–2019 shows a negative relationship between total debt (total liabilities/total assets) and long-term liabilities (long-term liabilities/total assets) and profitability (ROA), but a positive relationship between short-term liabilities and profitability (ROA). They also receive ambiguous results regarding the impact of the firm age, asset structure (fixed tangible assets/total assets) and financial liquidity (current ratio) on the profitability (ROA), i.e., their statistical significance and relationship with profitability varied in different models.

Tailab (2014) [66] analyzes 30 American Energy firms in the period of 2005–2013. He finds a significant negative relationship between total debt (total liabilities/total assets) and ROE (net income/total shareholders’ equity) and ROA (net income/total assets) and a significant positive relationship between a short-term debt (current liabilities/total assets) and ROE. Moreover, an insignificant relationship (negative or positive) is found between long-term debt (long-term liabilities/total assets), debt to equity (total liabilities/total equity) and profitability (ROA and ROE).

A negative relationship between financial leverage (total debt/total assets) and the age of companies and ROA is revealed in the study of 16 companies from the power and energy sector in Pakistan in the period 2001–2012 conducted by Fareed, Ali, Shahzad, Nazir and Ullah (2016) [6].

Apan and İslamoğlu’s (2018) [67] research of 10 energy firms quoted on the Borsa İstanbul, period 2008:Q1–2015:Q4, shows that profitability (ROA) is positively (significantly) affected by the liquidity ratio ((current assets − inventory)/short-term debts), but negatively among others by financial leverage (total debt/total assets) and tangible fixed asset/assets ratios.

Tekin (2022) [68] analyzes 16 companies from the Turkish energy sector and traded on Borsa Istanbul for the period of 2010:Q1–2019:Q4 and finds a significant negative impact of the leverage ratio (total debt/equity) and quick ratio ((cash + accounts receivables + marketable securities)/current liabilities) on profitability (ROE and ROA).

Research conducted by Bui and Nguyen (2021) [69] on 29 oil and gas companies listed in the Vietnam Stock Market in 2012–2018 shows a negative impact of financial leverage (total debt/(total debt + total equity)) on profitability measured by ROA, while fixed assets/total assets shows no relationship with it.

Referring to the results of our research and to the results obtained by other researchers analyzing companies from the energy sector, it should be noted that the variables that most often influence profitability are these related to the capital structure (combination of equity, long-term debt (liabilities) and short-term debt (liabilities)). However, it is not possible to determine a clear direction of their relationship with profitability (negative or positive), which is confirmed by the results of both our research and those of others from the energy sector, e.g., [64,65,66], and others sectors, e.g., [34,46].

As for the remaining analyzed variables (company age, fixed assets/total assets ratio, current ratio, fixed assets/current assets ratio and total liabilities/total equity ratio), their relationship with profitability is ambiguous (both in terms of the statistical significance, as well as the direction of influence), which is also confirmed by the results obtained by other researchers, e.g., [2,25,26,50,56,58,60].

5. Conclusions

The aim of this article is to examine which selected internal factors influence the profitability (ROA) of companies in the energy sector in Poland and how they do so, over the period 2018–2021, taking into account two groups: all types of activities (984 companies) and electricity production (508 companies).

The research is carried out on an annual basis to determine whether the impact of independent variables on profitability is constant in particular years or whether it changes, and whether the analyzed internal factors have the same impact on profitability, regardless of the type of business activity.

The research over the analyzed four-year period reveals that:

- In all ROA models, ratios relating to the capital structure appear as statistically significant, with the indicator informing about the degree of use of equity to finance the activities of energy companies appearing as many as seven times (in four models for all companies and in three models for electricity production companies); however, ratios informing about the degree of debt utilization (i.e., long-term liabilities and short-term liabilities to total assets) appear in half of the models, both in the group of all companies from the energy sector and in the group of electricity production enterprises. The indicator regarding the relationship between long-term liabilities and short-term liabilities appears in half of the ROA models, but only in the group of all companies operating in the energy sector. Interestingly, the impact of the total equity/total assets ratio on ROA is always positive. However, the impact of other statistically significant capital structure ratios on ROA varies both in the analyzed years (it is negative or positive) and in groups of enterprises.

- A statistically significant positive impact on ROA has the fixed assets/total assets ratio, which appears only in two models (one in each group) and the current ratio, which appears only in one model, in the group of all companies in the energy sector.

- A negative relationship with ROA is demonstrated by the age of the company, which is statistically significant only in one model in the group of all companies in the energy sector.

- Factors such as the fixed assets/current assets ratio and the total liabilities/total equity ratio not even once have a statistically significant impact on profitability (ROA) in any of the surveyed groups of enterprises.

The conducted research shows that in the energy sector, factors related to the capital structure (total equity/total assets, long-term liabilities/total assets, short-term liabilities/total assets and long-term liabilities/short-term liabilities ratios) in particular have a statistically significant impact on profitability measured by ROA, and the aforementioned factors appear in various combinations in all eight ROA models.

The results of the research show that the use of equity to finance the activities of energy companies seems to be particularly beneficial because the total equity/total assets ratio occurs in as many as seven out of eight econometric models and always has a positive impact on the return on assets (ROA). The remaining analyzed factors related to the structure of assets (fixed assets/total assets ratio), financial liquidity (current ratio) and the age of the company appear as statistically significant in the models quite rarely, having different effects on ROA (positively or negatively). However, variables such as the fixed assets/current assets and total liabilities/total assets ratios do not have a statistically significant impact on ROA at all in any of the surveyed groups of enterprises.

As the results of the research show, the number of independent variables in ROA econometric models, the way they affect the dependent variable (positive or negative) and the degree of model fit (R2) differ, both in the individual years covered by the analysis and in the two groups of companies. This means that it is not possible to clearly and finally determine which factors do and how they affect profitability. However, the frequency of the appearance of specific independent variables in the models may indicate their importance in shaping the dependent variable.

Our recommendations are as follows. The research results suggest that managers, in order to shape profitability (measured by ROA), should pay special attention to the capital structure, i.e., the proportions of the use of equity, long-term liabilities and short-term liabilities, to finance the operations of energy companies (as these independent variables appeared most often in ROA models). This is related, among other things, to the cost of capital and the level of debt (too much can increase the risk of insolvency or even lead to bankruptcy). Other analyzed factors, such as the asset structure (the share of fixed assets in total assets) or financial liquidity, also have an impact on the return on assets; therefore, their use in energy companies should also be considered.

What is very important is that the research shows a large diversity of factors shaping ROA in econometric models, the way they affect the dependent variable (positively or negatively) and the degree of model fit (R2), both in individual years and in the two groups of companies studied. This proves that it is not possible to clearly and finally determine which factors do and how (positively or negatively) they affect profitability. This influence can change over time depending on the circumstances, which indicates the need for the continuous involvement of decision makers in the management process and making decisions which are reliable and appropriate to the situation analyses.

Our work does have limitations. The research is conducted for two groups, i.e., 984 companies from the energy sector, regardless of the type of activity, and 508 electricity production companies. As the results show, the ROA models for individual groups differ both in terms of the statistically significant variables included in them, as well as in terms of the direction of their impact. Therefore, further, in-depth research may be focused on other types of activities in this sector, e.g., energy trade, transmission and distribution, to capture the relationships between various internal factors and profitability.

Moreover, the research is conducted in the four-year period (2018–2021), including two years before the COVID-19 pandemic (2018–2019) and two years during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2021). Interestingly, ROA models containing only internal factors affecting profitability in 2020–2021 have the highest coefficients of determination (R2), which might indicate that they explain a larger % of the observed variability than the coefficients of determination (R2) for models from 2018–2019, which are much lower. However, due to the adopted aim of this article and the research methods used, it is not possible to explain the reasons for these differences. This may be another interesting area for further scientific research.

This article only analyzes the impact of selected internal factors on the profitability (measured by ROA) of companies from the energy sector in Poland. However, the profitability of companies is shaped by a much broader set of factors, not only internal, but also external, which result from the external environment, including fiscal policy, business cycles and political crises. In this context, further interesting research may concern the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic or the war in Ukraine on the profitability of companies from the energy sector in Poland.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R. and K.C.-L.; methodology, K.C.-L.; software, validation, formal analysis, K.C.-L.; investigation, resources, data curation, S.R. and K.C.-L.; writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, S.R. and K.C.-L.; visualization, K.C.-L.; supervision, S.R. and K.C.-L.; project administration, funding acquisition, S.R. and K.C.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Koradia, V.C. Profitability Analysis—A Study of Selected Oil Companies in India. Indian J. Appl. Res. 2013, 3, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agegnew, A.; Gujral, T. Determinants Of Profitability: Evidence From Selected Manufacturing Company In Hawassa, Ethiopia. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 6, 8309–8322. Available online: https://journalppw.com/index.php/jpsp/article/download/9105/5924/10533 (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Banda, F.M.; Edriss, A.-K. What Factors Influence the Profitability of Firms in Malawi? Evidence from the Non-Financial Firms Listed on the Malawi Stock Exchange. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2022, 12, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jafari, M.K.; Al Samman, H. Determinants of Profitability: Evidence from Industrial Companies Listed on Muscat Securities Market. Rev. Eur. Stud. 2015, 7, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filatov, E. Analysis of profitability of production of enterprises in the field of transportation and storage of the Irkutsk region. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 63, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fareed, Z.; Ali, Z.; Shahzad, F.; Nazir, M.I.; Ullah, A. Determinants of Profitability: Evidence from Power and Energy Sector. Stud. Univ. Babe-Bolyai Oeconomica 2016, 61, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Akhtar, M.; Haris, M.; Muhammad, S.; Abban, O.J.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Energy crisis, firm profitability, and productivity: An emerging economy perspective. Energy Strategy Rev. 2022, 41, 100849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhandi, D.; Sipahutar, M.A.; Odang, N.K. The Effect of GRDP Sector Composition on Economic Growth in the Lake Toba Region. J. Ekon. Dan Studi Pembang. 2021, 13, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raźniak, P.; Dorocki, S.; Rachwał, T.; Winiarczyk-Raźniak, A. The role of the energy sector in the command and control function of cities in conditions of sustainability transitions. Energies 2021, 14, 7579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Achievements of the von der Leyen Commission. Eur. Green Deal 2024, 2024, 1–8. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/fs_24_1391 (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Sobolewski, M. Europejski Zielony Ład—W stronę neutralności klimatycznej. Infos. Biuro Analiz Sejmowych 2020, 9, 1–4. Available online: https://orka.sejm.gov.pl/WydBAS.nsf/0/5A874F6E5DAB64DCC12585AC002A3997?OpenDocument (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Our World in Data. Poland: Energy Country Profile. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/energy/country/poland (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- Statistics Poland. Energy Efficiency in Years 2011–2021. 2023. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/environment-energy/energy/energy-efficiency-in-poland-2011-2021,10,2.html (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Odyssee-Mure. Poland|Energy profile, March 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.odyssee-mure.eu/publications/efficiency-trends-policies-profiles/poland.html (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Szymańska, E.J.; Kubacka, M.; Woźniak, J.; Polaszczyk, J. Analysis of Residential Buildings in Poland for Potential Energy Renovation toward Zero-Emission Construction. Energies 2022, 15, 9327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymańska, E.J.; Kubacka, M.; Polaszczyk, J. Households’ Energy Transformation in the Face of the Energy Crisis. Energies 2023, 16, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institut Rousseau. Road to Net Zero. In Poland Factsheet; 2024; pp. 1–10. Available online: https://institut-rousseau.fr/road-2-net-zero-en/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Institiute Rousseau. Road to Net Zero. In Executive Summary; 2024; pp. 1–9. Available online: https://institut-rousseau.fr/road-2-net-zero-en/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- European Commission. The European Green Deal. Communication from the Commission. 2019. Brussels, 11.12.2019, COM(2019) 640 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0640 (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Kędzierski, L. Factors Shaping the Profitability of Ethical Financial Investments of Firms. Stud. Gdańskie. Wizje i Rzeczyw. 2020, XVII, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škuflić, L.; Mlinarić, D.; Družić, M. Determinants of construction sector profitability in Croatia. Zb. Rad. Ekon. Fak. U Rijeci/Proc. Rij. Fac. Econ. 2018, 36, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škuflić, L.; Mlinarić, D.; Družić, M. Determinants of firm profitability in Croatia’s manufacturing sector. In International Conference on Economic and Social Studies; Proceedings Book; 2016; pp. 269–282. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/153449801.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Vuković, B.; Milutinović, S.; Mirović, V.; Milićević, N. The profitability analysis of the logistics industry companies in the balkan countries. Promet-Traffic Transp. 2020, 32, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rađo, D.; Peštović, K. Factors of Profitability: Evidence from the Serbian Manufacturing Sector. ENTRENOVA-ENTerprise REsearch InNOVAtion 2022, 8, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, H.A.; Derbali, A. Which is Important in Defining the Profitability of UK Insurance Companies: Internal Factors or External Factors? Rev. Econ. Financ. 2020, 18, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, T.K.; Arora, A.; Le, T. Firm-Specific Determinants of Firm Performance in the Hospitality Sector in India. Sustainability 2023, 15, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, R.A.; Isa, M.A.M.; Zaharum, Z.; Baharudin, A.M. Profitability Determinants of Technology Companies: A Study From ACE Market of Bursa Malaysia. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2022, 12, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, L.I.; Harjono, J.A.; Mahadwartha, P.A. Determinants of Profitability for Manufacturing Companies in Indonesia 2018–2020. J. Ris. Akunt. Dan Keuang. 2022, 10, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, L.K.; Magar, M.R. Factors affecting the profitability of Nepalese insurance companies. Nepal. J. Insur. Soc. Secur. 2021, 4, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, T. Determinants of profitability: A study on manufacturing companies listed on the Dhaka Stock Exchange. Asian Econ. Financ. Rev. 2020, 10, 1496–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharaibeh, O.K.; Bani Khaled, M.H. Determinants of profitability in Jordanian services companies. Invest. Manag. Financ. Innov. 2020, 17, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, L.; Vasiu, D. Capital Structure and Profitability. The Case of Companies Listed in Romania. Stud. Bus. Econ. 2022, 17, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proença, P.; Laureano, R.M.S.; Laureano, L.M.S. Determinants of Capital Structure and the 2008 Financial Crisis: Evidence from Portuguese SMEs. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 150, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, A.; Biger, N.; Mathur, N. The Effect of Capital Structure on Profitability: Evidence from the United States. Int. J. Manag. 2011, 28, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Stoiljković, A.; Tomić, S.; Leković, B.; Matić, M. Determinants of Capital Structure: Empirical Evidence of Manufacturing Companies in the Republic of Serbia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modigliani, F.; Miller, M.H. Corporate Income Taxes and the Cost of Capital: A Correction. Am. Econ. Rev. 1963, 53, 433–443. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, A.; Biger, N.; Pai, C.; Bhutani, S. The Determinants of Capital Structure in the Service Industry: Evidence from United States. Open Bus. J. 2009, 2, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thippayana, P. Determinants of Capital Structure in Thailand. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 143, 1074–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhagaiah, R.; Gavoury, C. The Impact of Capital Structure on Profitability with Special Reference to IT Industry in India. Manag. Glob. Transit. 2011, 9, 371–392. [Google Scholar]

- Nickell, S.; Nicolitsas, D. How does financial pressure affect firms? Eur. Econ. Rev. 1999, 43, 1435–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branch, B. The costs of bankruptcy. A review. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2002, 11, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs, and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantzalis, C.; Park, J.C. Agency costs and equity mispricing. Asia-Pac. J. Financ. Stud. 2014, 43, 89–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubita, M.F.; Alsawalhah, J.M. The Relationship between Capital Structure and Profitability. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2012, 3, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid, M.A.; Abdullah, A.; Kamaruzzaman, N.A. Capital Structure and Profitability in Family and Non-Family Firms: Malaysian Evidence. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 31, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Salim, M.; Yadav, R. Capital Structure and Firm Performance: Evidence from Malaysian Listed Companies. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 65, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohman, M.; Fitriyah. Firm Value: The Mediating Effects Of Capital Structure On Profitability, Size, And Asset Structure. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Manag. 2024, 5, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, R.R.; Sari, M.; Astuty, W. Effect of Business Risk, Company Size, and Asset Structure on Capital Structure with Profitability as an Intervening Variable (Case Study on Manufacturing Companies on the Indonesia Stock Exchange). Int. J. Res. Rev. 2021, 8, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq Bhutta, N.; Hasan, A. Impact of Firm Specific Factors on Profitability of Firms in Food Sector. Open J. Account. 2013, 2, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burja, C. Factors Influencing The Companies’ Profitability. Ann. Univ. Apulensis Ser. Oeconomica 2011, 13, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Bashir, Z.; Manzoor, S.; Akram, M.N. Determinants of Firm’s Financial Performance: An Empirical Study on Textile Sector of Pakistan. Bus. Econ. Res. 2013, 3, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, C.A. Efficiency of Financial Ratios Analysis for Evaluating Companies’ Liquidity. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Stud. 2018, 4, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimon, G.; Nakonieczny, J.; Chudy-Laskowska, K.; Wójcik-Jurkiewicz, M.; Kochański, K. An Analysis of the Financial Liquidity Management Strategy in Construction Companies Operating in the Podkarpackie Province. Risks 2022, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antczak, J.; Horzela, I.; Nowakowska-Krystman, A. Influence of Financial Liquidity on the Competitiveness of Defense Industry Enterprises. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2021, XXIV, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgünes, K. The Effect of Liquidity on Financial Performance: Evidence from Turkish Retail Industry. Int. J. Econ. Financ. 2016, 8, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.L.; Nguyen, V.C. The determinants of profitability in listed enterprises: A study from Vietnamese Stock Exchange. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpiabhele, E.; Tafamel, A.E. Liquidity Management and Profitability of Consumer and Industrial Goods Companies in Nigeria. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2020, 8, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majerowska, E.; Gostkowska-Drzewicka, M. Impact of the Sector and of Internal Factors on Profitability of the Companies Listed on the Warsaw Stock Exchange. Dyn. Econom. Models 2018, 18, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahabuddin, M.; Khan Synthia, S. Determinants of Firm Profitability: Evidences from Bangladeshi Manufacturing Industry. Econ. Financ. Lett. 2020, 7, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Pei, R.; Pan, J. The evolution and determinants of Chinese property insurance companies’ profitability: A DEA-based perspective. J. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2021, 6, 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blažková, I.; Dvouletý, O. Sectoral and Firm-Level Determinants of Profitability: A Multilevel Approach. Int. J. Entrep. Knowl. 2018, 6, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervan, M.; Pervan, I.; Ćurak, M. Determinants of firm profitability in the Croatian manufacturing industry: Evidence from dynamic panel analysis. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraz. 2019, 32, 968–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewski, J.W. Financial Liquidity and Debt Recovery Efficiency Forecasting in a Small Industrial Enterprise. Risks 2022, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škulánová, N. Impact of selected determinants on the financial structure of the mining companies in the selected countries. Rev. Econ. Perspect. 2020, 20, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek-Kosmala, M.; Błach, J.; Gorzeń-Mitka, I. Does capital structure drive profitability in the energy sector? Energies 2021, 14, 4803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tailab, M. The Effect of Capital Structure on Profitability of Energy American Firms. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Invent. 2014, 3, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Apan, M.; İslamoğlu, M. Determining the impact of financial characteristics on firm profitability: An empirical analysis on Borsa Istanbul energy firms. WSEAS Trans. Bus. Econ. 2018, 15, 547–559. [Google Scholar]

- Tekin, B. What are the internal determinants of return on assets and equity of the energy sector in Turkey? Financ. Internet Q. 2022, 18, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, M.T.; Nguyen, H.M. Determinants Affecting Profitability of Firms: A Study of Oil and Gas Industry in Vietnam. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).