Switching Behavior in the Polish Energy Market—The Importance of Resistance to Change

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Research Sample Characteristics

4.2. Study Results

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Besant-Jones, J.E. Reforming Power Markets in Developing Countries: What Have We Learned? World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mollard, M. Switching costs and the pricing strategies of incumbent suppliers on the British retail electricity market. In Proceedings of the 4th Conference on Applied Infrastructure Research, Berlin, Germany, 15–17 November 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Joskow, P.L. Lessons learned from electricity market liberalisation. Energy J. 2008, 29, 9–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.; Sen, A. The Energy Transition: Key Challenges for Incumbent and New Players in the Global Energy System; OIES Paper: ET; The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies: Oxford, UK, 2021; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Defeuilley, C. Retail competition in electricity markets. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Chi, Y.; Mamaril, K.; Berry, A.; Shi, X.; Zhu, L. Communication-Based Approach for Promoting Energy Consumer Switching: Some Evidence from Ofgem’s Database Trials in the United Kingdom. Energies 2020, 13, 5179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiskanen, E.; Apajalahti, E.-L.; Matschoss, K.; Lovio, R. Incumbent energy companies navigating energy transitions: Strategic action or bricolage? Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 28, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiyev, N. Oligopoly Trends in Energy Markets: Causes, Crisis of Competition, and Sectoral Development Strategies. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2021, 11, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawin, R. National Report of the President of URE; Energy Regulatory Office: Warsaw, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Keaveney, S.M. Customer Switching Behavior in Service Industries: An Exploratory Study. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, G.; Groth, M.; Wiedmann, K.-P. An Examination of Consumers’ Motives to Switch Energy Suppliers. J. Mark. Manag. 2005, 21, 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulczycka, J.; Lipińska, A. Barriers to liberalization of the Polish energy-sector. Appl. Energy 2003, 76, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzeziński, S.; Zborowski, K.; Pietrasieński, P. The effect of the liberalization of electricity market in Poland. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2013, 7, 152–160. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Reiner, D. Why Consumers Switch Energy Suppliers: The Role of Individual Attitudes. Energy J. 2017, 38, 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deller, D.; Giulietti, M.; Loomes, G.; Price, C.W.; Moniche, A.; Jeon, J.Y. Switching Energy Suppliers: It’s Not All About the Money. Energy J. 2021, 42, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Fehr, N.-H.M.; Banet, C.B.; Le Coq, C.; Pollitt, M.; Willems, B. Retail Energy Markets under Stress; Lessons Learnt for the Future of Market Design; Centre on Regulation in Europe (CERRE): Brussels, Belgium, 2022; pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Giulietti, M.; Price, C.W.; Waterson, M. Consumer Choice and Competition Policy: A Study of UK Energy Markets. Econ. J. 2005, 115, 949–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, R. Consumer switching behavior and bundling: An empirical study of Japan’s retail energy markets. Int. J. Econ. Policy Stud. 2022, 16, 443–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, M.; Price, C.W. The Role of Attitudes and Marketing in Consumer Behaviours in the British Retail Electricity Market. Energy J. 2018, 39, 153–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolli, F.; Vona, F. Energy market liberalization and renewable energy policies in OECD countries. Energy Policy 2019, 128, 853–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kungl, G. Stewards or sticklers for change? Incumbent energy providers and the politics of the German energy transition. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 8, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salm, S.; Wüstenhagen, R. Dream team or strange bedfellows? Complementarities and differences between incumbent energy companies and institutional investors in Swiss hydropower. Energy Policy 2018, 121, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Conner, M.; Norman, P. Understanding the intention-behavior gap: The role of intention strength. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 923464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konerding, U. Formal models for predicting behavioral intentions in dichotomous choice situations. Methods Psychol. Res. 1999, 4, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. J. Res. Personal. 1985, 19, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, K.D.; Hill, R.P. Life Satisfaction, Self-Determination, and Consumption Adequacy at the Bottom of the Pyramid. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 38, 1155–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirkov, V.; Ryan, R.M.; Youngme, K.; Kaplan, U. Differentiating Autonomy from Individualism and Independence: A Self-Determination Theory Perspectiveon Internalization of Cultural Orientations and Weil-Being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy Mechanism in Human Agency. Am. Psychol. 1982, 37, 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R.; Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory of Organizational Management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 361–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, H.S.; Taylor, S.F.; James, Y.S. “Migrating” to new service providers: Toward a unifying framework of consumers’ switching behaviors. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2005, 33, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanuwijaya, E.; Oktavia, T. Analysis of the Factors Influencing Customer Switching Behaviour of The Millennials in Digital Banks. J. Syst. Manag. Sci. 2023, 13, 122–133. [Google Scholar]

- Haridasan, A.C.; Fernando, A.G.; Balakrishnan, S. Investigation of consumers’ cross-channel switching intentions: A push-pull-mooring approach. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 1092–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akwensivie, D.M. Switching behaviour and customer relationship management-the Iceland experience. Br. J. Mark. Stud. 2014, 2, 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Z.; Qiu, X. Social Exclusion and Switching Behaviour of Green Products: The Mediating role of Control Demand. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Advances in Energy, Environment and Chemical Science (AEECS 2021) E3S Web of Conferences, Shanghai, China, 26–28 February 2021; Volume 245, p. 02040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M.M.; Kumar, D.P. Factors Influencing the Behavior of the Mobile Phone users to Switch their Service Providers in Andhra Pradesh. Glob. J. Manag. Bus. Res. E Mark. 2016, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Oreg, S. Personality, context, and resistance to organizational change. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2006, 15, 73–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descotes, R.M.; Pauwels-Delassus, V. The impact of consumer resistance to brand substitution on brand relationship. J. Consum. Mark. 2015, 32, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Asrani, C.; Jain, T. Resistance to Change in an Organization. OSR J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 20, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo del Val, M.; Martínez Fuentes, C. Resistance to change: A literature review and empirical study. Manag. Decis. 2003, 41, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarantou, V.; Kazakopoulou, S.; Chatzoudes, D.; Chatzoglou, P. Resistance to change: An empirical investigation of its antecedents. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2018, 31, 426–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafizh Damawan, A.; Azizah, S. Resistance to Change: Causes and Strategies as an Organizational Challenge. Adv. Soc. Sci. Educ. Humanit. Res. 2019, 395, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbart, J.A. Organizational Change: The Challenge of Change Aversion. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, F.; Wong, C. Impact of Traditional Behavior of Customers, Employees, and Social Enterprises on the Fear of Change and Resistance to Innovation. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 923094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endrejat, P.C. When to challenge employees’ comfort zones? The interplay between culture fit, innovation culture and supervisors’ intellectual stimulation. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2021, 42, 1104–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.S. Challenges of Managing an Organizational Change. Adv. Manag. 2012, 5, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert-Pandraud, R.; Laurent, G. Why do Older Consumers Buy Older Brands? The Role of Attachment and Declining Innovativeness. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.; Cai, L.A. Brand Knowledge, Trust and Loyalty—A Conceptual Model of Destination Branding. In Proceedings of the International CHRIE Conference-Refereed Track, San Francisco, CA, USA, 31 July 2009; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doney, P.M.; Cannon, J.P. An examination of the nature of trust in buyer–seller relationships. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Amoah, J.; Bashiru Jibril, A.; Bankuoru Egala, S.; Keelson, S.A. Online brand community and consumer brand trust: Analysis from Czech millennials. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2149152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munuera-Aleman, J.L.; Delgado-Ballester, E.; Yague-Guillen, M.J. Development and Validation of a Brand Trust Scale. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2003, 45, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajavi, K.; Kushwaha, T.; Steenkamp, J.-B.E.M. In Brands We Trust? A Multicategory, Multicountry Investigation of Sensitivity of Consumers’ Trust in Brands to Marketing-Mix Activities. J. Consum. Res. 2019, 46, 651–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A.; Gabriel, M.; Figueiredo, J.; Oliveira, I.; Rêgo, R.; Silva, R.; Oliveira, M.; Meirinhos, G. Trust and Loyalty in Building the Brand Relationship with the Customer: Empirical Analysis in a Retail Chain in Northern Brazil. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.W.; Mittal, V. Strengthening the Satisfaction-Profit Chain. J. Serv. Res. 2000, 3, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanah, D.; Handoko, B.; Hafas, H.R.; Hermansyur; Harahap, D.A. Customer Retention: Switching Cost and Brand Trust Perspectives. Palarch’s J. Archaeol. Egypt/Egyptol. 2021, 18, 3552–3561. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, G.T.; Lee, S.H. Consumers’ trust in a brand and the link to brand loyalty. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 4, 341–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudzewicz, A.; Strychalska-Rudzewicz, A. The Influence of Brand Trust on Consumer Loyalty. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2021, 24, 454–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gielens, K.; Steenkamp, J.-B.E. Branding in the era of digital (dis)intermediation. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2019, 36, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Peng, M.Y.-P.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, G.; Chen, C.-C. Expressive Brand Relationship, Brand Love, and Brand Loyalty for Tablet PCs: Building a Sustainable Brand. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, A.W.; Paul, J.; Trott, S.; Guo, C.; Wu, H.-H. Two decades of research on nation branding: A review and future research agenda. Int. Mark. Rev. 2019, 38, 46–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, A.; Kitapci, H.; Zehir, C. Creating Commitment, Trust and Satisfaction for a Brand: What is the Role of Switching Costs in Mobile Phone Market? Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 99, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, M.; Enric, R.J. Managing Customer Switching Costs: A Framework for Competing in the Networked Environment. Manag. Res. 2003, 1, 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Yen, Y.-S. Can perceived risks affect the relationship of switching costs and customer loyalty in e-commerce? Internet Res. 2010, 20, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, C.; Picón, A. Multi-dimensional analysis of perceived switching costs. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2012, 41, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Manstrly, D. Enhancing customer loyalty: Critical switching cost factors. J. Serv. Manag. 2016, 27, 144–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-G.; Park, K.; Lee, J. A firm’s post-adoption behavior: Loyalty or switching costs? Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2014, 114, 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y. Customer participation and the roles of self-efficacy and adviser-efficacy. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Ao, S.; Dai, J. Estimating the switching costs in wireless telecommunication market. Nankai Bus. Rev. Int. 2011, 2, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.A.; Loveland, J.M.; Loveland, K.E. The impact of switching costs and brand communities on new product adoption: Served-market tyranny or friendship with benefits. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2019, 28, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.A.; Reynolds, K.E.; Mothersbaugh, D.L.; Beatty, S.E. The positive and negative effects of switching costs on relational outcomes. J. Serv. Res. 2007, 9, 335–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blut, M.; Beatty, S.E.; Evanschitzky, H.; Brock, C. The Impact of Service Characteristics on the Switching Costs–Customer Loyalty Link. J. Retail. 2014, 90, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Ma, J.; Ji, C. Study of social ties as one kind of switching costs: A new typology. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2015, 30, 648–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison of Two Theoretical Models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Chen, Q.; Kitkuakul, S. Regulatory focus and technology acceptance: Perceived ease of use and usefulness as efficacy. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2018, 5, 1459006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Chang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yan, J. Understanding usage of Internet of Things (IOT) systems in China: Cognitive experience and affect experience as moderator. Inf. Technol. People 2017, 30, 117–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yechiam, E.; Aharon, I. Experience-based decisions and brain activity: Three new gaps and partial answers. Front. Psychol. 2012, 2, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, F.; Curado, M. The role of observation, cognition, and imagination in Keynes’s approach to decision-making. EconomiA 2019, 20, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.-H.; Lu, K.-L. Enhancing effects of supply chain resilience: Insights from trajectory and resource-based perspectives. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2017, 22, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, M.R.; Camgoz, S.M.; Karan, M.B.; Berument, M.H. The switching behavior of large-scale electricity consumers in The Turkish electricity retail market. Energy Policy 2022, 160, 112701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, H.; Foley, A.; Del Rio, D.F.; Smyth, B.; Laverty, D.; Caulfield, B. Customer engagement strategies in retail elec-tricity markets: A comprehensive and comparative review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 90, 102611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Seet, P.-S.; Ryan, M.; Iranmanesh, M.; Cripps, H.; Salam, A. Determinants of switching intention in the electricity —An integrated structural model approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 69, 103094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, N.E.; Huebner, G.M.; Fell, M.J.; Shipworth, D. Two energy suppliers are better than one: Survey experiments on consumer engagement with local energy in GB. Energy Policy 2020, 147, 111891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P.; Webb, T.L. The Intention–Behavior Gap. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2016, 10, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Number of Respondents | Percentage of Sample | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 610 | 50.2 |

| Male | 606 | 49.8 | |

| Age (years) | 18–29 | 158 | 13.0 |

| 30–39 | 300 | 24.7 | |

| 40–49 | 360 | 29.6 | |

| 50–59 | 257 | 21.1 | |

| 60 or more | 141 | 11.6 | |

| Household size (number of individuals) | 1 | 97 | 8.0 |

| 2 | 309 | 25.4 | |

| 3 | 335 | 27.5 | |

| 4 | 327 | 26.9 | |

| 5 or more | 148 | 12.2 | |

| Period of cooperation with the current energy supplier (years) | Less than one | 127 | 10.4 |

| One to two | 67 | 5.5 | |

| Over two to five | 148 | 12.2 | |

| Over five to ten | 194 | 16.0 | |

| Over ten | 680 | 55.9 | |

| Experience in changing energy suppliers | First supplier (1) | 1078 | 88.7 |

| Second supplier (2) | 110 | 9.0 | |

| Third supplier | 16 | 1.3 | |

| Fourth supplier or more | 11 | 0.9 | |

| Frequency of contact with the current energy supplier | Every few years | 560 | 46.1 |

| Once a year | 355 | 29.2 | |

| 2–4 times a year | 213 | 17.5 | |

| 5 or more times a year | 88 | 7.2 | |

| Discriminant Validity | Convergent Validity | Construct Reliability | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension | Criterion of Fornell-Larcker | AVE | Cronbach’s Alfa | CR | |||||

| RtC | BT | PSC | PEofC | SI | |||||

| Resistance to change | RtC | 0.661 | 0.437 | 0.694 | 0.699 | ||||

| Brand trust | BT | 0.561 | 0.816 | 0.667 | 0.887 | 0.889 | |||

| Perceived switching costs | PSC | −0.086 | 0.065 | 0.658 | 0.433 | 0.655 | 0.683 | ||

| Perceived ease of changing suppliers | PEofC | 0.006 | 0.196 | −0.086 | 0.747 | 0.558 | 0.775 | 0.788 | |

| Switching intention | SI | −0.388 | −0.309 | 0.098 | 0.136 | 0.882 | 0.778 | 0.911 | 0.913 |

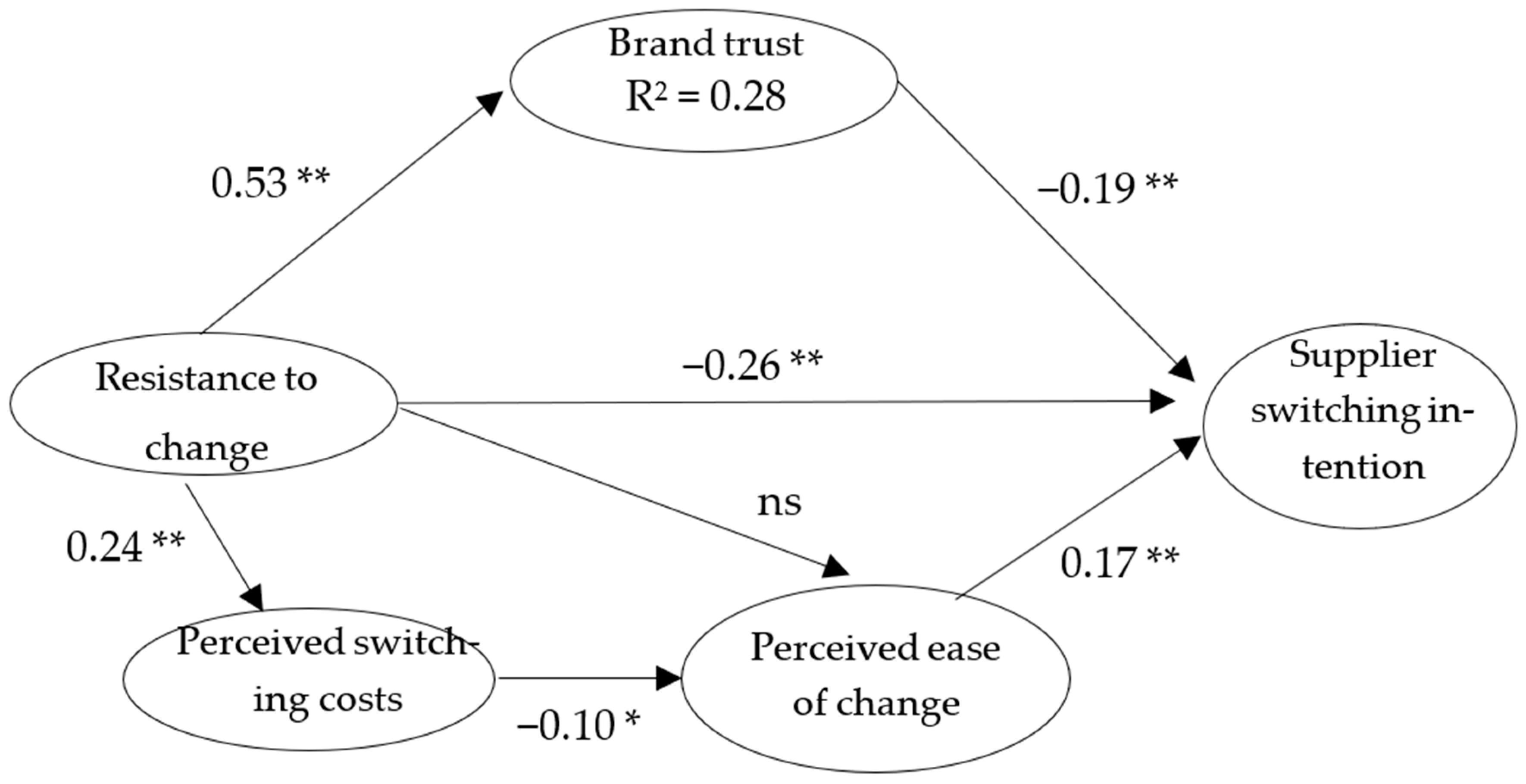

| Hypothesis | p-Value | Estimates | Acceptance or Rejection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Resistance to change => Brand trust | 0.000 | 0.53 | Acceptance |

| H2 | Resistance to change => Supplier switching intention | 0.000 | −0.26 | Acceptance |

| H3 | Resistance to change => Perceived ease of change | 0.087 | 0.06 | Rejection |

| H4 | Resistance to change => Perceived switching costs | 0.000 | 0.24 | Acceptance |

| H5 | Brand trust => Supplier switching intention | 0.000 | −0.19 | Acceptance |

| H6 | Perceived switching costs => Perceived ease of change | 0.009 | −0.10 | Acceptance |

| H7 | Perceived ease of change => Supplier switching intention | 0.000 | 0.17 | Acceptance |

| RtC | PSC | PEoC | BT | SI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSC | |||||

| Total Effect | 0.269 ** | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Direct Effect | 0.269 ** | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indirect Effect | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PEoC | |||||

| Total Effect | 0.05 ns | −0.109 * | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Direct Effect | 0.079 ns | −0.109 * | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indirect Effect | −0.029 * | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| BT | |||||

| Total Effect | 0.549 ** | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Direct Effect | 0.549 ** | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indirect Effect | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SI | |||||

| Total Effect | −0.379 ** | 0.203 * | 0.2 ** | −0.162 ** | 0 |

| Direct Effect | −0.361 ** | 0.225 ** | 0.2 ** | −0.162 ** | 0 |

| Indirect Effect | 0.019 ** | −0.022 * | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lipowska, I.; Lipowski, M.; Dudek, D.; Mącik, R. Switching Behavior in the Polish Energy Market—The Importance of Resistance to Change. Energies 2024, 17, 306. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17020306

Lipowska I, Lipowski M, Dudek D, Mącik R. Switching Behavior in the Polish Energy Market—The Importance of Resistance to Change. Energies. 2024; 17(2):306. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17020306

Chicago/Turabian StyleLipowska, Ilona, Marcin Lipowski, Dariusz Dudek, and Radosław Mącik. 2024. "Switching Behavior in the Polish Energy Market—The Importance of Resistance to Change" Energies 17, no. 2: 306. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17020306

APA StyleLipowska, I., Lipowski, M., Dudek, D., & Mącik, R. (2024). Switching Behavior in the Polish Energy Market—The Importance of Resistance to Change. Energies, 17(2), 306. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17020306