1.2. Previous Research on Use and Energy Use in Second Homes

Access to a second home is a prevalent phenomenon in the Nordic countries, including Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Denmark, as well as in the United Kingdom, France, Germany, the Czech Republic, South Africa, Canada, the United States, and Australia [

7,

8]. During the 1960s, 1970s, and early 1980s, the construction of second homes experienced a boom, leading to the addition of cottages in locations on the urban periphery across the Nordic countries [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. A substantial part of second homes in Sweden, Norway, and Finland, between 80 and 90 per cent, were purpose-built. However, the stock of second homes is supplemented by converted single-family houses, which previously served as primary residences but had become obsolete or abandoned because of increased demands for modern, comfortable housing, or outmigration as a result of urbanisation [

9,

13,

14]. Consequently, converted second homes are common in rural areas in the Nordic countries. Approximately 50% of all Nordic households have access to a second home [

10]. According to earlier studies, 26% of the population in Norway own a second home, but 40% utilise second homes [

15], and in Sweden, about 54% of the population owns or has access to a second home through relatives and friends [

5,

16]. In Finland, 62% of the population has regular access to one or more second homes [

17], and in Denmark, 14% own a second home, but it is likely that more people have access to one [

18]. The frequency of use of second homes in these three countries generally follows the same pattern. In Finland, second homes are used on average for 75 days per year, in Sweden, for 71 days, and in Norway, for between 26 and 51 days per year (with a national mean of 47 days per year). However, there are significant regional differences in the frequency of use because of location and standard [

13].

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the purchase and utilisation of second homes, driven by factors such as “flight shame”, which has encouraged more holidays to be taken closer to one’s permanent residence and within the home country, rather than abroad, as well as the COVID-19 pandemic, which has facilitated remote work—a trend likely to endure. Second homes serve various purposes, including use as summer or winter residences and variations in between, and their operation and maintenance are diverse. Additionally, many second homes have been converted into permanent residences and vice versa. However, the climate impact resulting from the increased use of second homes, alongside potential renovations and energy efficiency improvements in building systems and materials, remains underexplored, despite the environmental and climate implications of second homes being a topic of interest since the 1970s [

19]. The cultural and historical values associated with second homes have also been insufficiently researched. Studies from various European regions indicate that simpler second homes are being renovated to enhance comfort. For instance, in Norway, the increased standard of facilities in second homes has led to greater energy use and climate impact [

20]. Similarly, in France, there has been a rise in energy consumption, larger building spaces, and increased land use pressure from second homes [

21]. A Danish study reveals that second homes used for rental purposes exhibit higher standards and increased energy consumption, with electricity predominantly used for heating, in contrast to the broader Danish building stock [

22]. A questionnaire survey among Norwegian second homeowners, aiming to understand the Norwegian second home phenomenon in relation to sustainability (environmental, social, and economic), shows a low interest in reducing energy use [

23]. Steffansen (2017) observes an increase in the use of second homes by both owners and others during the pandemic, while also noting the blurred distinction between second and permanent homes. He further reports an average increase in living space, material use, energy consumption, and standards per second home. In Finland, a national survey called the Second Homes Barometer provides information on the location of second homes, available facilities and amenities, and owners’ future plans [

24]. Local surveys of second homeowners in Finland have been used to study travel habits and the associated climate impact of second homes [

25]. Similar trends have been observed outside Europe, for example, in South Africa [

26]. Electricity consumption in second homes has steadily increased over the years, particularly as these properties are increasingly used year-round by retirees and families on holiday. The more intensive year-round use has driven up electricity consumption, whether for space heating or hot water production. In Norway, electricity consumption increased by 97% from 1973 to 2005 [

27]. This trend is partly due to the fact that most second homes were originally built for summer use and are therefore often poorly insulated. Andersson et al. (2008) simulated energy consumption in Danish second homes, combining top-down estimations based on time series of total electricity consumption and the number of second homes, with bottom-up analyses of measured electricity consumption in specific second homes, considering heat losses, electricity used for appliances, and various user patterns [

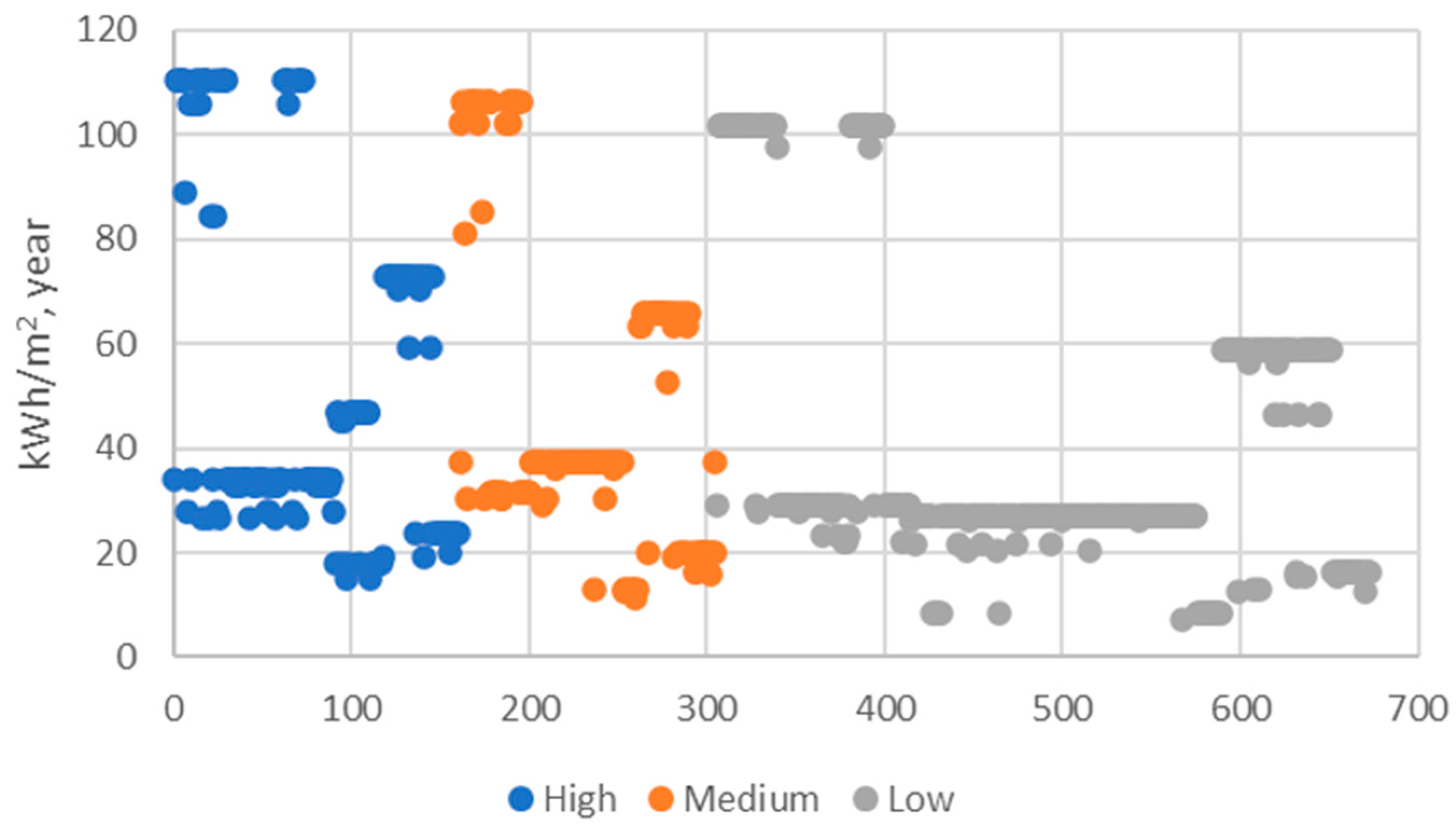

28]. Based on a survey of 700 second homeowners from selected areas in Denmark and interviews with representatives from typical groups of second homeowners, as well as stakeholders in rental, construction, electricity supply, regulatory processes, and renewable energy plants, a catalogue of recommendations for energy savings was developed [

29]. This catalogue is aimed at the mentioned actors, including second homeowners themselves. The study concludes that the potential for energy savings in second homes is substantial, with solutions ready to be implemented. However, there is a lack of awareness of these solutions and a belief that investing in energy savings in second homes could be beneficial [

29].

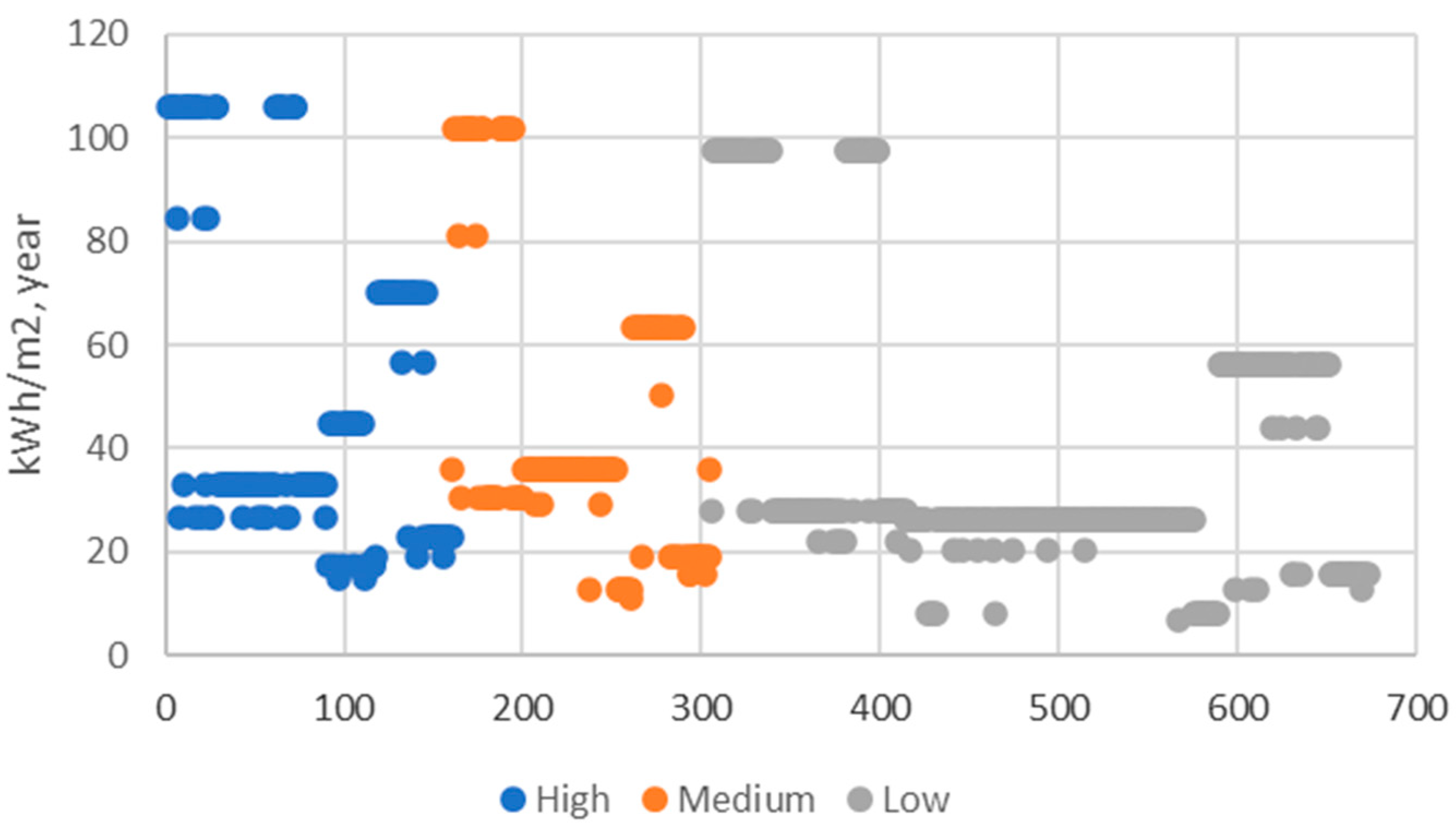

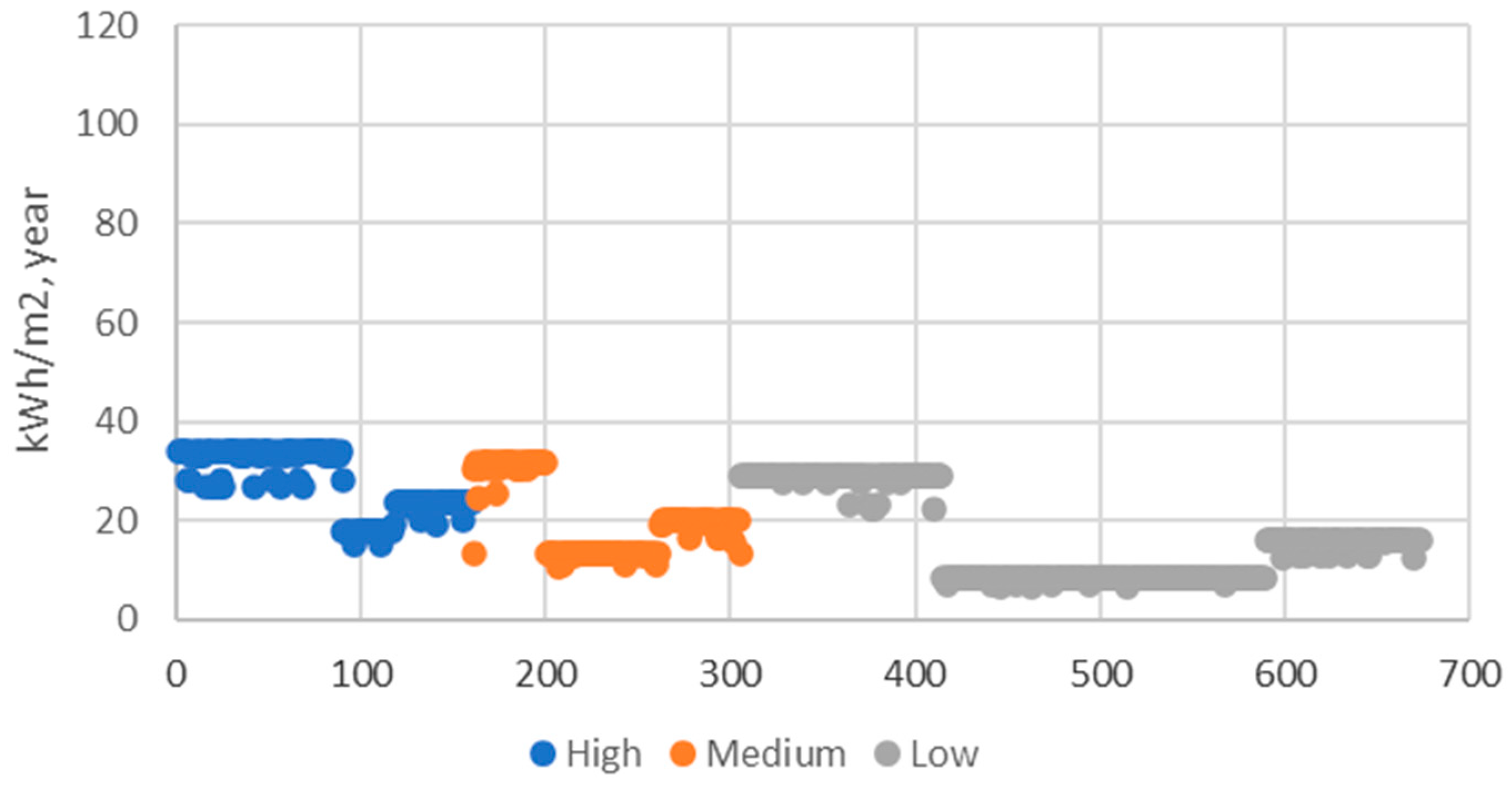

The second home stock in Sweden consists of a little more than 600,000 second homes, [

5]. Second homes are here defined as valuation units that do not have registered residents and are taxed as agricultural units with building(s), single-family house units with building(s), single-family houses on freehold land, or single-family house units with building value below SEK 50,000 corresponding to EUR 4325 or USD 4755 [

5]. Even though the energy use for the Swedish second home stock decreased from 3.5 TWh in 2011 to 2.83 TWh in 2021, which means approximately 20% during the last 10 years [

5,

6], more ambitious measures must be taken to reach the 2030 goals. Mata et al. (2013) estimate the potential for reducing energy use in Swedish residential buildings with permanent use, considering that a number of energy measures were performed, to be 53% based on 1400 sample buildings, and the results show that the measures with the greatest savings are those involving heat recovery systems (22%) and reduced indoor temperature (14%) [

30]. Although second homes are not mandated to possess an energy performance certificate, some homeowners have voluntarily obtained one. As of August 2022, there were 10,766 second homes in Sweden with an issued energy performance certificate (EPC), accounting for 1.8% of the total number of second homes. The average specific energy use of these 10 766 second homes was estimated to be 119 kWh/m

2 [

31]. Most Swedish second homes are in energy classes E, F, and G. The poor energy performance can be explained by the fact that 80–90% were purpose-built and intended mainly for use during the summer. The majority of second homes have direct electricity as their main heating system, but some have installed an air-to-air heat pump, presumably to reduce electricity consumption. Ground source heat pumps are more common in second homes with higher energy classes (A–D), probably because it is a significantly larger investment than installing an air-to-air heat pump and quite a few of the houses are heated by wood stoves or tiled stoves [

31]. The poor energy performance, together with a high proportion of electrical heating, make this group of buildings an interesting target group for energy efficiency measures.

In addition, there is very limited research on the energy renovation of second homes and its impact on cultural–historical values. Second homes represent great economic and cultural–historical but also social values that must not be neglected or distorted. It must be ensured that energy-efficient measures do not cause moisture damage or devastate cultural–historical values [

32,

33]. At the same time, second homes must also provide a good indoor environment regarding both thermal comfort and air quality, which becomes especially important if users’ time spent in second homes increases. However, results from a Finish study measuring relative humidity and temperature indoors hourly in unheated, uninsulated cottages and outdoors indicated that the monthly average vapour content of air inside is lower than the average vapour content outside most times except for some occasions during spring and when a cottage is occupied [

34]. However, winter visits involving heating induce drying of the cottage. The relative humidity stays mainly below 80%, which is a critical level for mould growth on organic materials. When constant heating was introduced to increase the temperature by approximately 3 °C, it resulted in a decrease in the relative humidity by 10%. This would be enough to substantially decrease the risk of condensation and mould growth considerably [

34]. An even better approach would be to introduce intermittent heating, when climatic conditions are critical in terms of the risk of mould growth [

34,

35]. This must be thoroughly analysed and validated in more second homes before any general recommendations can be made. Despite the existence of several prior studies on energy use, including some that focus on energy use and the potential for energy efficiency in second homes [

25,

28,

34,

36], there remains a dearth of information on current usage patterns, energy use, heating sources, and energy saving potential in second homes.