1. Introduction

The European Union (EU) has been implementing an energy transition according to a green agenda (in line with the 2030 Agenda, coordinated with other international organizations and forums, i.e., United Nations, World Economic Forum), which is committed to international differentiation based on quality environmental facits (reducing the carbon footprint, avoiding CO

2 emissions, not using fossil fuels, etc., [

1,

2]). In this sense, a series of commitments has been reached, the whole of which is the Green Deal [

3,

4] and its realization is the green transition, which is analyzed here.

The green transition requires large investments, but currently in Europe there are insufficient savings, due to the influence of Keynesian policies. These have been applied for decades and are founded on stimulating consumption (to sustain aggregate demand), assuming the trap called the “paradox of saving”, attributed to Keynes [

5], but based on a mercantilist dispute [

6].

To finance the green transition, fiscal and monetary economic policies have been applied, based on green taxes, plus monetary and budgetary expansions. This occurred with the Next Gen EU Funds [

7], which stimulated a financial bubble, guaranteeing all green investment (whether productive or not), hoping to be returned later [

8]–or not, as happened before the Great Recession of 2008, with sovereign green bonds, but now the last guarantor is the EU [

9].

Therefore, the green transition (which started in 2019 with the

Green Deal [

3,

4], has been financed via taxes, expansive spending, and exponential debt, giving rise to growing monetary inflation and social deflation [

10,

11].

For this reason there is endogenous and continuous inflation in the European Union, due to carrying out public policies that trigger the cobra effect (public intervention that causes a greater evil than the one intended to be corrected [

12]), requiring instead the readjustment effect (given the declining productivity, urgent transformation of the production process and structure via intensification of geek training and talent development [

2,

13,

14,

15]).

It can be surmised that the European Green Deal will have the following consequences: First, the so-called European greenflation paradox can be realized from wealthy people (European politicians who earn more than EUR 300,000/year) to middle-class (South-European voters who earn less that EUR 25,000/year). In order to achieve greater social prosperity in the future due to a looming climate risk (action pro SGD 13), current prosperity and wellbeing is reduced (violation of SGD 1–3 and 7–12). This results in a real and lasting risk of social impoverishment (starting with energy poverty [

16]), especially for the middle class and middle-income countries (as southern and eastern countries). Also, there are studies which defend better results in climate action from high-socioeconomic-status people compared to the current coercive interventionism [

17]. Second, second-round effects are likely to materialise: The advance of the green industry is associated with considerable restrictions in the primary sector and the transport sector. In addition to stricter regulations, the conversion of land in favour of wind and solar farms, and reductions in subsidies are likely to have a significant impact on economic activity in the traditional sectors (crowding-out effect [

12,

13,

14]). Similarly, higher taxes on fuel, the levying of new road tolls, the abolition of air transport for distances of less than 200 kilometers, etc. These issues have a similar effect on the transport sector with negative impact on the supply chain, potentially causing shortages and higher prices, further reducing the purchasing power of the middle class. These government interventions can reduce productivity and profitability in these sectors [

18]. Third, the green industry is not labour intensive, so unemployment will be higher (i.e., a combustion car factory normally employs more than 1000 people, an electric car factory less than 100) etc. There are more other unwanted and second round effects [

12,

13,

14], but they will be studied as future research lines.

2. Theoretical and Methodological Framework

In this paper we intend to use the findings of the Austrian School of Economics (AE) [

19,

20], and those of F. Hayek in particular, as a tool for analyzing the problem outlined above [

21,

22].

The insights of the AE are based on methodological individualism in ontological as well as semantic and explicatory terms [

13,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. From an ontological point of view, the so-called autonomy thesis according to which individuals, their attitudes, their behavior and their actions must be seen as the sole creative forces in society, serves as the fundament. In this respect, only the existence of individuals is accepted. Only individuals can have aspirations and goals and only individuals can act. Therefore, social phenomena superordinate to individuals such as society or a class- are regarded as purely conceptual constructs. In addition to that, methodological individualism makes use of semantics in which statements about social phenomena are formulated as propositions about observable behavior or the understandable intentions of individuals. (The State is not an individual: thanks to extreme methodological individualism, it is possible to discover that the State is a political organization, like a firm, constituted by agents and institutions; in this way, AE and New-Institutional Schools go beyond the mainstream analysis [

29]). With regard to explication—for example, to explain specific social phenomena—methodological individualism uses an explanans that consists of general hypotheses about the dispositions of individuals in addition to singular propositions. The general hypothesis can either be psychologically based or filled with the principle of rationality [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35].

Hayek’s approach emphasizes the subjective character of an individual’s data and goals that largely determine his or her actions. He assumes that the explication of an action can be grasped with the help of introspection [

23,

24]. Therefore, explanations of an action must be kept as explanations of principle and only allow statements in the form of patterns that exclude certain results (i.e., lead to a restriction of the maximum amount of explananda [

36]).

Furthermore, the approach of the AE and Hayek’s in particular is based on a specific view of the human being [

37,

38,

39]: Individuals are characterized by different physical and mental abilities and skills. In addition, they can differ considerably in their needs and thus their preference structures. The individual‘s perception of actual circumstances, which is selective due to cognitive limitations, means that individual actions are based on more or less accurate expectations [

40]. In addition, individuals have different types and amounts of resources. These resources consist not only of material goods, but also include rights, immaterial goods, transferable means and skills, and abilities that are tied to the individual and thus inalienable. Quite simply, resources are everything that an individual can use to influence their physical- and social-environment. Furthermore, an individual‘s resources are scarce. Despite this diverse heterogeneity, individuals exhibit a universal characteristic: the desire to improve their situation and living conditions [

41,

42,

43,

44]. This impetus is concretized by individual needs, to which an individual allocates different utility values.

The individual’s efforts to pursue their own individually different objectives, which may well conflict with each other, constitute competition as a social process of mutual adaptation of individual actions and expectations [

43]. This process forces individuals to use dispersed knowledge which exists in a decentralized manner, and to search for new knowledge. Thus, the permanent acquisition of knowledge creates an evolutionary process. In this sense competition is a process of discovery [

45].

According to Hayek [

46], the free development of competition with all its advantages presupposes the existence of general rules. The character of the general rules also limits the scope for state intervention.

Hayek’s concept of general rules is based on the distinction between laws (universal rules of just conduct or nomos) and commands (thesis) [

38,

39,

47]. Whereas the latter are “applicable only to particular people or in the service of the ends of rulers” [

48], laws (that is, general rules) are universal, open, abstract, certain, and consistent [

49,

50].

The requirement of universality: A law must satisfy the demand for personal indifference and therefore applies to all individuals [

51]. In this context personal indifference means that the scope is not restricted to certain persons or groups [

38,

48,

49,

52]. In this respect, universality is congruent with the postulate of isonomy, that is, equality before the law. Thus, the requirement of personal indifference has the effect that a rule, regardless of its content, which nonetheless can be discriminatory or privileging, is universally applicable to all individuals regardless of their class, their religion, their skin color, etc. Personal indifference is supplemented by situational indifference. Accordingly, a rule has to be designed in such a way that no specific circumstances need to be cited that limit the applicability of the rule. The rule must therefore be created for an unknown number of cases [

48,

53]. This means that further possibilities of discrimination against individuals are excluded. Time concretization and spatial indifference are additional requirements. In this context, the time concretization means that the rule must apply to the future and a retroactive effect is excluded [

49].

The requirement of openness: The openness of a rule is achieved by not prescribing certain actions, but rather by forbidding actions that would interfere with the individual freedom of others [

38,

46]. This restricts the individual’s scope of action. However, within his scope of action, an individual can make his choice from at least formally conceivable alternative actions. If, on the other hand, concrete actions are prescribed, the rule loses its purposeless character and degenerates into a command. An instruction to act in the sense of a command can, however, be easily disguised as a prohibition to act in the case of a limited number of alternative actions and thus fulfils the requirement of openness from a purely formal point of view. However, the principle of universality prevents a far-reaching restriction of such scope for arbitrariness. In addition, the requirement of openness must not be purely formal but must be interpreted in terms of content.

The requirement of abstractness: According to Hayek, the rules must be applicable to an unknown number of cases and persons in the future [

38,

48]. To be able to do this, the rule must be abstract; otherwise, it would not be applicable to an unknown number of future cases. The content of the rules must therefore neither be based on a single, specific issue, nor may proper names be mentioned in the rules [

49]. Logically, the requirement of abstraction, which is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a universal rule, can be interpreted as a consequence of the universality principle on the semantic and teleological level.

The requirement of certainty: According to Hayek (1960) the set of rules must be designed in such a way that the rules or their content belong to the data that an individual can use as the basis for his decisions. This expresses the demand for certainty which relates to the content of the rules, the area of application, and the time dimension [

38].

In this context, it must be taken into account that human behavior is based on expectations. An individual’s assessment of permanently valid individual freedom and in this way a relief of expectation formation presupposes that, on the one hand, actions to be omitted are clearly defined as such. On the other hand, the application of rules takes place without exceptions. In this respect, the demand for certainty inevitably corresponds with the universality principle. If the content of the set of rules is certain and it is applied without restrictions, then the individual perceives the set of rules as a “natural obstacle” [

49]. Certainty in the area of rule content and the area of application ensures that the set of rules is incorporated into the plans of the individual on a reliable basis. In this way it makes purposeful action possible in the first place [

49].

In this respect, the criterion of certainty goes beyond the requirement of universality, because a rule that is certain in its scope and content does not leave any room for discretion nor does it allocate any room to maneuver when applying the rule based on another additional criterion. A rule would, for example, correspond to at least the first level of the universality criterion if its object were a prohibition of a certain action, but exceptions can be made to this prohibition if the specific circumstances meet certain criteria. However, this rule would not be certain, since it would only have to be checked in a specific application of whether the prerequisites for an exception to this rule are met. However, certainty in the area of the rule’s content and the rule’s area of application remains irrelevant if the duration of the validity of the rule is unknown or if the set of rules is subject to high dynamics. As a result, the requirement for unlimited validity only consequently complements the other two components. However, it cannot be denied that in a developing society there are adjustment requirements for the set of rules. In this respect, an unlimited validity of the entire set of rules can never be achieved, but must have ideal value from the start. Hayek [

52] is satisfied with the demand that avoidable uncertainty be avoided. This requirement is satisfied if the period of validity of the rule is specified, as is already required in the context of the requirement for universality.

The set of rules represents an external institution; as long as it satisfies the demand for certainty, it allows individuals to exclude certain future consequences of their actions and thus to reduce the uncertainty to a certain extent.

The requirement of consistency: Contradictions between individual rules of the rule set lead to uncertainties about the consequences of concrete actions. The consequence is a loss of certainty. Therefore, the structure of the rules has to be consistent (Hayek 1976); that is, the rule’s content and its application need to be coordinated with one another so that the rules do not conflict with one another [

38]. Therefore, a certain action may not have different consequences depending on the rule applied. Only with a consistent set of rules does the connection between action and its effects become evident for the individual, which helps to facilitate the formation of expectations, and which contributes to the reduction of uncertainty.

The requirement of consistency has indispensable meanings for the certainty of the set of rules as well as for the further development of the set of rules.

What does this mean for governmental interventions?

Hayek assumes that the interaction of individuals has to be understood as a complex phenomenon and that only pattern prediction can be made about it. Therefore, governmental interventions must meet Hayek’s requirements for general rules. This means that a governmental intervention must be general, abstract, open, and certain. In addition, it must fit consistently into the existing set of rules.

Also, this research pays attention to Mise’s theorem on economic calculus and the impossibility of the normative interventionism in the way of coercive central planning [

29,

54,

55,

56]. The AE analysis is more deductive and abductive [

27], in opposition to mainstream economics (more inductive, also “ultra-empiricists” [

57,

58]). We explain here the economic principles and their empiric illustrations, to promote the dialogue with other economic schools [

10,

11] (because there is a review of ideas, public opinion, and initiatives on the topic [

59,

60,

61]): however, we are concerned that New-Keynesians and Post-Keynesians are going to feel uncomfortable with this mainline analysis [

13,

62].

3. Characteristics of the European Green Deal

The European Union intends to make Europe the first climate-neutral continent by 2050. For this objective the European Commission presented a strategy named The European Green Deal (EGD) in 2019 which aims to promote environmental as well as economic and social transformation and is central to the implementation of EU commitments under the Paris Climate Agreement [

3,

4].

The EGD aims to reduce emissions and pollution while promoting economic growth and the creation of new jobs and will in doing so initiate far-reaching changes in numerous sectors, including energy, industry, transport, agriculture, and biodiversity.

The main objectives of the EGD besides climate neutrality by 2050 are the promotion of a sustainable economy, the protection of biodiversity, the zero-pollution target aiming at drastically reducing pollutant emissions in the air, water, and soil, the establishment of a sustainable agriculture and of an affordable, reliable and sustainable energy supply, with a focus on renewable energy and energy efficiency. While climate neutrality means that all remaining emissions have to be offset by absorption measures such as reforestation, promoting a sustainable economy means that the economy should be circular by using resources more efficiently and minimizing waste. In order to achieve these goals, the implementation of a comprehensive package of measures was planned.

A large part of the measures relates to climate protection and emissions trading. For example, the European Climate Law of 30 June 2021 enshrined the goal of climate neutrality by 2050 in law and set interim targets for 2030, which provide for a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions of at least 55% compared to 1990. Emission trading is also to be reformed and extended to new sectors.

In the area of clean energy, the expansion of renewable energy sources such as wind and solar energy is to be given greater support. In addition, measures to improve energy efficiency in buildings and industry are to be initiated in order to reduce energy consumption.

In the sustainable industry field of action, industry is to be incentivized to develop and use low-emission technologies. In addition, the circular economy is to be promoted in order to make production and consumption patterns sustainable and reduce the consumption of resources.

In the area of mobility, zero-emission vehicles are to be promoted and the charging infrastructure for electric vehicles and the promotion of public transport are to be driven forward. Furthermore, the productivity of freight transport is to be improved so that emissions can be reduced.

In the agriculture and biodiversity field of action, the intention is to establish a “farm to fork” strategy. This is intended to improve sustainability in food production and reduce the use of pesticides and fertilizers. At the same time, measures to protect and restore nature are to be initiated.

These projects imply a considerable financial requirement, which the European Commission estimates at around 260 billion euros per year. This financial volume is to be financed from the EU budget, the NextGenerationEU recovery program and other EU programmes such as the Just Transition Mechanism and Horizon Europe. On the other hand, private funds are to be mobilized.

In order to mitigate the social disruption resulting from this project, measures will be taken to ensure that no one is disadvantaged by the transition to a green economy, in particular by creating new jobs and supporting workers in affected sectors.

The measures should be implemented according to the following schedule:

- -

2019: Announcement of the European Green Deal.

- -

2021: Fit for 55 Package (The “Fit for 55” package is a comprehensive set of laws and measures relating to emissions trading, renewable energies, the organisation of transport and mobility, land use, forestry and agriculture, as well as tax measures [

63,

64]).

- -

2021: Adoption of the European Climate Law (In addition to climate planning and reporting by the member states, the European Climate Law focuses in particular on the establishment of adaptation and financing measures [

63,

64]).

- -

2022: REPowerEU Plan (With the REPowerEU plan, the European Union is responding to the energy crisis and geopolitical tensions, in particular the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, with the aim of reducing EU energy dependence on Russian fossil fuels and accelerating the transition to renewable energies [

65]).

- -

2022: Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (Directive 2010/31/EU) (With this directive the European Union intends to improve the energy efficiency of buildings in the European Union).

- -

2023: Update of the Green Deal Industrial Plan (The “Update of the Green Deal Industrial Plan” (GDIP) aims to strengthen the competitiveness of European industry against the backdrop of increasing global competition and geopolitical uncertainties in the context of the green transformation).

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. European Macroeconomics Data and Green Deal

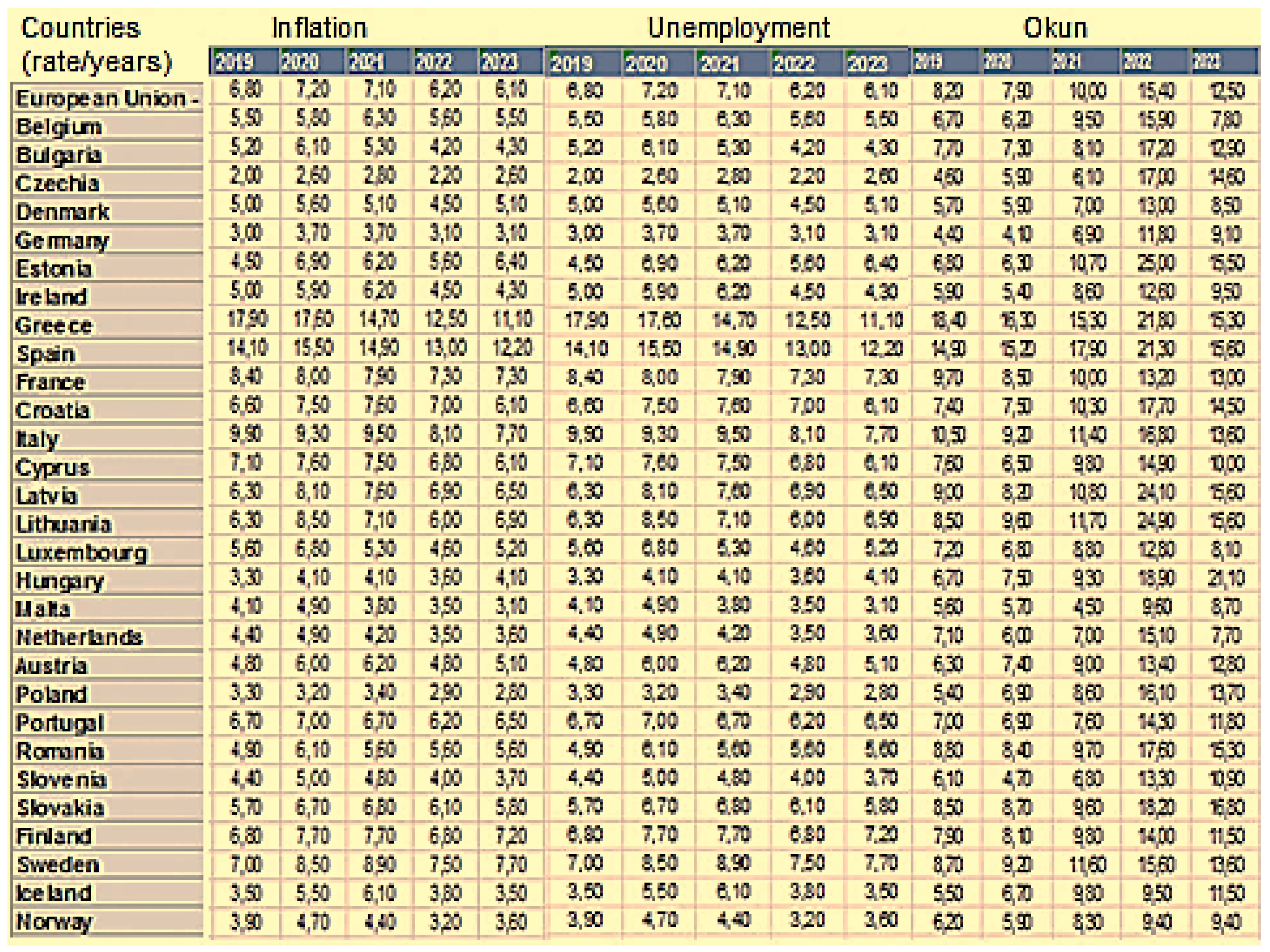

According to the data from the European Central Bank and Eurostat, the annual inflation rate in the Eurozone was 1.7% in 2019 and 8.5% in 2022 (5.3% in 2023); and the unemployment rate was 1.2% in 2019 and 8.4% in 2022 (5.5% in 2023). So, the Phillips curve is not correct, as inflation and unemployment move in the same level (not in an inverse direction), and new employment is financed with European funds (based on debt). How is this possible? Let us go back to the green policies and their financing.

The implementation of green policies, particularly under the European Union’s Green Deal [

3,

4], has been marked by initiatives aimed at achieving climate goals (SGD 13), but with other unwanted effects (with negative impact in SGD 1–3 and 7–12). These policies, while essential for promoting environmental sustainability (according to the green interventionism), also bring about notable economic challenges, such as inflationary pressures and disruptions in economic welfare (many of them as second round effects). To understand the broader implications of these policies, it is crucial to examine key events within the Green Deal timeline and their corresponding impacts on economic indicators such as the Okun Index (or misery index [

66,

67,

68,

69,

70].

The European Green Deal has seen several pivotal events since its announcement in 2019, with projection in the new industrial strategy: green reindustrialization [

64]. Each of these events has played a role in shaping the economic landscape of the EU, influencing factors such as unemployment and inflation (the bases for stagflation). By analyzing the relationship between these events and the fluctuations in the Okun Index (as positive economics: to explain the complex relations in social phenomena), we can gain insights into how the Green Deal’s policies affect economic stability and welfare. This analysis highlights the necessity of balancing environmental objectives with economic resilience, as illustrated by the diverse impacts of major Green Deal initiatives on the EU-27 economies.

The European Union’s ambitious Green Deal aims to combat climate change and promote environmental sustainability through various green policies and initiatives. However, these efforts are not without economic consequences. This section analyses the impact of green policies on inflation and economic welfare, summarizing recent findings on how the green transition, particularly through the EU Fit-for-55 package, affects energy prices, production costs, and overall economic stability. We explore the potential for green policies to drive inflationary pressures, disrupt labor markets, and lead to sectoral imbalances, highlighting the complexities and challenges of balancing environmental goals with economic stability

4.2. Summary of Recent Findings

A recent analysis reveals that the green transition, as embodied in the EU Fit-for-55 package, involves a linear increase in fossil energy prices over two decades. This rise in energy prices escalates production costs, reduces output, and diminishes real wages. The inflationary consequence of this price adjustment critically depends on monetary policy management and the flexibility of prices and wages [

71].

4.2.1. Inflationary Pressures

Green policies and initiatives like the Green Deal, while aiming to combat climate change and promote environmental sustainability, can have several negative impacts on inflation and economic welfare. A critical analysis of the mainstream economic literature highlights these adverse effects (from heterodox approaches there are more contributions —for this research, we have only paid attention to mainstream contributions to apply the mainline analysis from AE—and in a complementary way, the New-Institutional Schools: Law & Economics, Public Choice, Constitutional Economics, etc. [

12,

13,

29].

One significant concern is the potential for green policies to contribute to inflationary pressures—this is a question which requests an answer, because there is a lacuna to fill-. Climate intervention was a debate until 2019 (when the Green Deal was passed), during the period of low inflation and loose monetary policy in European economies, with almost zero interest rates and large asset purchase programmes. However, with shocks and crisis like COVID-19 or the war in Ukraine, the macroeconomic context has changed too [

72,

73]. According to AE and its capital-based macroeconomics [

10,

11], money is not neutral and it can be distributed by governments with budgets and bonds, and by central banks with exchange and interest rates and other unconventional measures. So, the implementation of green taxes, subsidies for renewable energy, and stringent environmental regulations can increase production costs. These higher costs are often passed on to consumers in the form of increased prices for goods and services, thus contributing to overall inflation. Financial support with sovereign bonds to promote the green transition is another accelerator of inflation.

4.2.2. Economic Welfare and Consumption

Green policies have several effects (some mentioned), but one is the reduction in long-term consumption, as noted by Brita Bye [

74]. This reduction in consumption can negatively impact economic welfare, particularly for lower-income households that spend a larger proportion of their income on essential goods and services. The reallocation of resources towards green investments can lead to a decrease in immediate consumption, also undermining short-term economic welfare.

4.2.3. Unemployment and Labor Market Disruptions

Green growth policies can also disrupt labor markets and affect wage income distribution. Jean Château et al. [

75] highlight that the structural changes induced by decarbonization policies are likely to have significant consequences on labor–income distribution. These changes can lead to job losses in traditional energy sectors and increased unemployment in regions dependent on fossil fuel industries. The transition to green jobs may not be smooth or immediate, causing periods of economic instability and increased welfare dependency.

4.2.4. Taxation and Economic Efficiency

While proponents like A. Bovenberg [

76] suggest that green tax reform can generate a double dividend by improving environmental quality and economic efficiency, the reality can be more complex. P. Sørensen et al. [

77] argue that emission charges can improve the efficiency of the tax system by indirectly taxing pure profits. However, this can also lead to higher tax burdens on businesses, reducing their competitiveness and potentially leading to lower economic growth. Increased taxation and regulatory burdens can stifle innovation and investment, further exacerbating economic slowdowns.

4.2.5. Sectoral Imbalances and Investment Risks

The European Green Deal’s focus on climate and energy policy, as highlighted by Susanna Paleari [

78], can lead to sectoral imbalances. Overemphasis on green sectors may result in underinvestment in other crucial areas of the economy, leading to inefficiencies and potential economic stagnation. Moreover, the shift towards green investments carries inherent risks, as noted by Bert Scholtens [

79], where the economic benefits of green fiscal policies may not always materialize as expected, leading to potential financial instability.

4.2.6. Impact of Monetary Policy

Monetary policy plays a crucial role in managing inflationary pressures during the green transition. A well-calibrated policy that focuses on core inflation, temporarily ignoring the rise in energy prices, can avoid significant inflationary deviations. This approach can replicate an efficient equilibrium even with nominal price and wage rigidities [

71].

In scenarios where the prices of non-energy goods and wages are rigid, optimal monetary policy might have to tolerate some inflationary deviations in both goods and wages to minimize costly price dispersion. This underscores the importance of well-planned and coordinated policies during the green transition to avoid significant adverse effects [

71].

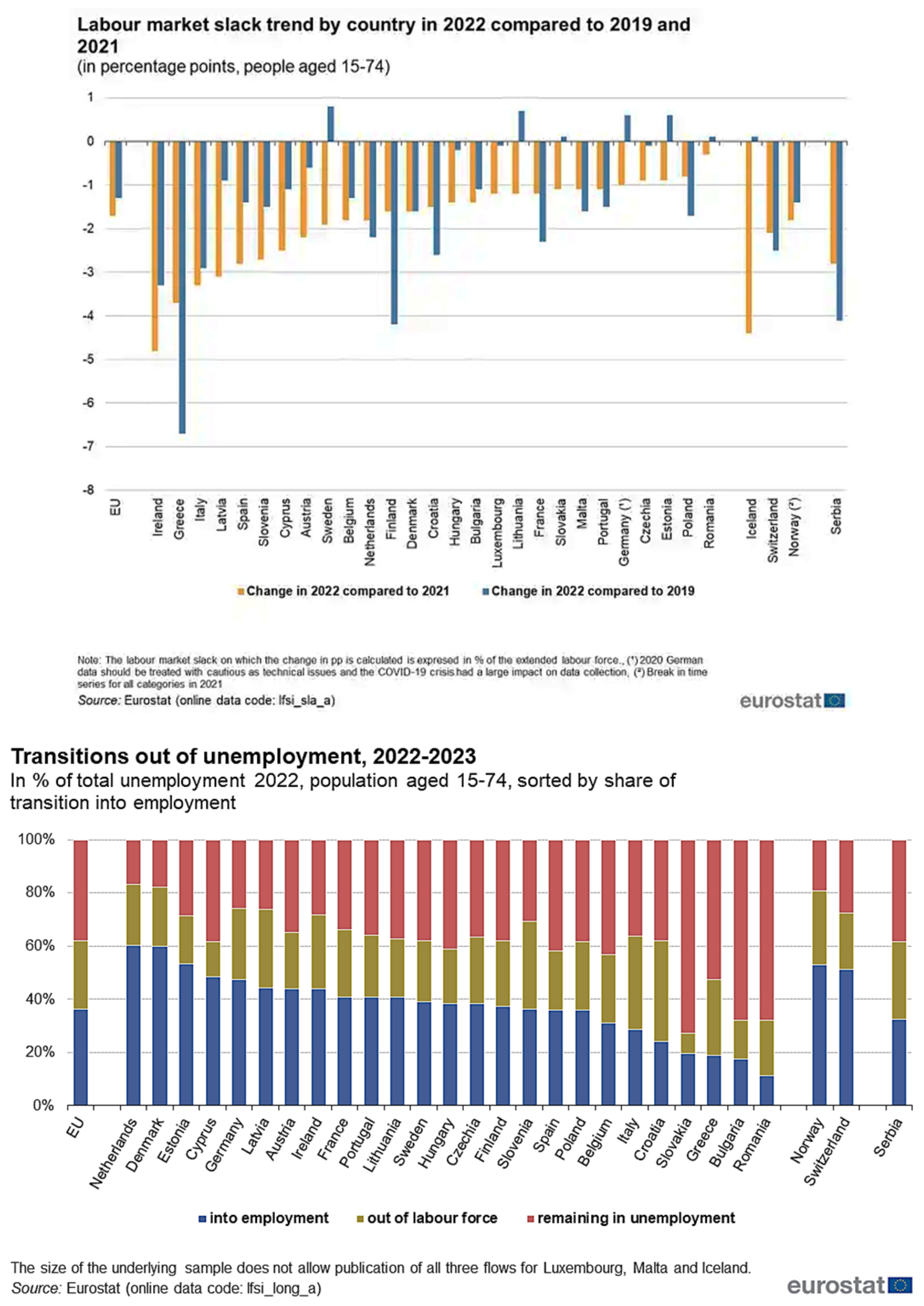

In summary, while green policies and the Green Deal aim to foster a sustainable future, they can also have negative impacts on inflation and economic welfare (with increasing discrepancies between nominal and real data and higher slack level). Enlarged production costs, reduced consumption, labor market disruptions, higher taxation, sectoral imbalances, and investment risks all contribute to potential economic challenges (with impact on the labor market, see

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

4.3. Green Deal Most Important Events

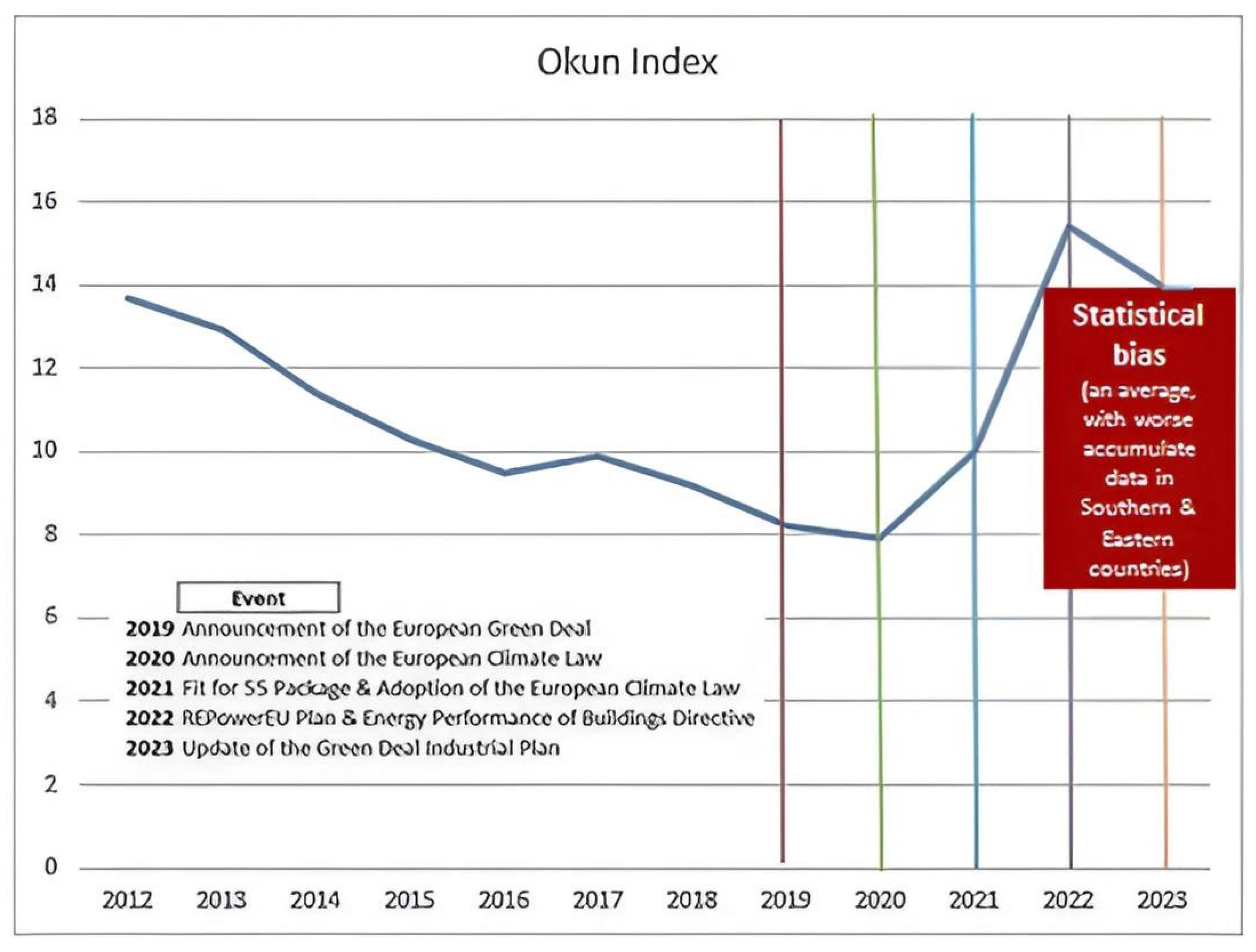

Relationship between the Okun Index and Green Deal Events in the EU-27

The Okun Index is an economic measure (based on Okun’s law: an empirical observation on a regularity relation [

66,

67]), that sums up the unemployment rate and inflation (in an empirical way, not normative, like Phillips’s law [

83]), providing a combined perspective of these two crucial variables. Over time, several significant events of the European Union’s Green Deal have coincided with fluctuations in this index. Here, we analyze these relationships, with special attention to the last five years, from 2019 to 2023:

- -

2019: Announcement of the European Green Deal and design of the strategic agenda and the pluriannual financial period (2021–2027 [

14]).

- -

2021: Fit for 55 Package, which is a set of proposals to revise and update EU legislation to promote more EU policies based on climate goals (passed by the Council and the European Parliament as part of the commitment with the Agenda 2030 [

84]). Adoption of the European Climate Law (from green growth to degrowth [

13]).

- -

2022: EU institutions pass REPowerEU Plan and Energy Performance of Buildings Directive. It was the peak of the Okun index for the second round effects (see

Figure 3).

- -

2023: Update of the Green Deal Industrial Plan, to promote the green transition (the financial support for digital and green jobs in traditional sectors is moved to the green industry, with crowding-out effect)

To interpret correctly the figure, it is important not to fall into statistical bias and a trap: by offering an average of the economies of the European Union, the evaluation within it is not really reflected, since in the economies of the south the problem is greater and more persistent, only camouflaged with the injection of new money from the next generation and other complementary funds.

Endogenous or exogenous factors? [

85,

86]. The significant rise in the Misery Index observed in 2022 can be attributed to exogenous factors such as the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, including unemployment spikes and economic downturns. Additionally, the inflationary pressures and economic disruptions caused by the war in Ukraine have likely contributed to this peak. These events underscore the importance of considering external factors beyond policy implementation when analyzing economic indicators. However, this is only the new macroeconomic context (as it was mentioned before), but an endogenous factor is the loose monetary policy in European economies before and after the Great Recession of 2008 (then the current inflation was sown into the economy a long time previously).

The post-pandemic economic recovery and recent geopolitical tensions have significantly influenced the index, highlighting the complexity of the interaction between economic policies and global conditions. However, the solution implemented in the European Union is more of fiscal and credit expansion, which means more inflation.

This analysis shows that although the Green Deal events aim to stabilize and improve the EU economy in the long term, short-term fluctuations in the Okun Index are inevitable due to various external and internal factors.

4.4. Green Deal and Austrian Economics

As we have seen, the Austrian (School of) Economics (AE) and Hayek in particular emphasize individual decisions, market mechanisms, and the role of entrepreneurs in economic activity. From this point of view, the European Union’s Green Deal shows some grave deficits.

According to Hayek, the free market is the most efficient method for allocating resources (spontaneous order [

37]). However, the EU Green Deal includes extensive government intervention and regulation aimed at managing the transition to a climate-neutral economy. Doing so, the Green Deal has to be considered as inefficient because it disrupts natural price formation and the adjustment of supply and demand.

AE considers the role of entrepreneurs as innovators and drivers of economic progress. According to AE, innovation arises from the free interaction of market participants and that competition produces the best solutions. The Green Deal includes tools that interfere deeply with the freedom of entrepreneurs by dictating to companies how they should manufacture their products and which technologies they should use.

Hayek in particular emphasizes that knowledge is decentralized in society and central planners can never have all the necessary information to make efficient decisions. However, the Green Deal requires extensive information processing and decision-making at a centralized level. Therefore, the Green Deal’s attempts will lead to bad investments and inefficient use of resources because they are not based on the specific, dispersed knowledge of the market participants.

According to Hayek, prices are the most important source of information in a market. Governmental intervention, such as subsidies or taxes to promote green technologies, distorts price signals and leads to false incentives.

Hayek also elaborates that human action is based on expectations. Therefore, individuals assess future uncertainties to make their plans and take risks. The Green Deal seems to be an attempt to reduce these uncertainties through government regulations, thereby restricting the dynamic adaptability of the market.

From the perspective of the AE, the Green Deal could be seen as a well-intentioned but inefficient attempt to achieve environmental goals through central planning and government intervention. The Austrian School would suggest that the free market is capable of finding the most efficient and sustainable solutions through price mechanisms and competition. Government intervention such as the Green Deal, on the other hand, could hinder innovation, distort market incentives, and lead to an inefficient allocation of resources.

As we have seen, the AE and Hayek in particular emphasize individual decisions, market mechanisms, and the role of entrepreneurs in economic activity. From this point of view the European Union’s “Green Deal” shows some grave deficits:

According to Hayek, the free market is the most efficient method for allocating resources. However, the EU “Green Deal” includes extensive government intervention and regulation aimed at managing the transition to a climate-neutral economy. Doing so, the Green Deal has to be considered inefficient because it disrupts natural price formation and the adjustment of supply and demand.

In addition to that, AE considers the role of entrepreneurs as innovators and drivers of economic progress. According to AE, innovation arises from the free interaction of market participants and t competition produces the best solutions. The Green Deal dwells on tools which interfere deeply into the freedom of entrepreneurs because it dictates to companies how they should manufacture their products and which technologies they should use. Instead, the AE argues that.: the technology helps to connect the dispersed knowledge and initiative of individuals (not the State, and even less from a coercive centralized planning [

13,

54,

55]).

According to Hayek, prices are the most important source of information in a market. As the Green Deal comes with governmental intervention, such as subsidies or taxes to promote green technologies, it distorts price signals and leads to false incentives.

As we have seen, Hayek elaborates that human action is based on expectations. Therefore, individuals assess future uncertainties to make their plans. They take risks. The Green Deal seems to be an attempt to reduce these uncertainties through government regulations. In this way it restricts the dynamic adaptability of the market.

In addition, the Green Deal is not being implemented in the form of general rules in Hayek’s sense. Neither the requirement of universality nor the criteria of openness, abstractness, certainty and consistency are met. For example, the Green Deal treats issues differently, e.g., economic sectors, which, according to Hayek, require equal treatment, thereby violating the principle of universality and, in particular, situational indifference. The criterion of openness, on the other hand, is partially fulfilled, as actions that do not fulfil the objectives of the Green Deal are still possible, but are associated with higher costs. The criterion of abstractness is violated, as concrete objectives for the actions of individuals and companies are set by the state. Furthermore, the projects associated with the Green Deal do not fulfil the requirement of certainty, as the measures of the Green Deal have been readjusted several times. The criterion of consistency is not met insofar as the instruments of the Green Deal may conflict with the other legal bases of the European Union, especially the unrestricted property rights.

Also, according to Mise’s theorem, the Green Deal, as inspiration of normative policies set and implanted in a coercive central planning way, is current evidence of the imposibility of economic calculus and a violation of the free single market into the European Union [

29,

54,

56].

5. Conclusions

The analysis of the “greenflation paradox” within the context of the European Union’s Green Deal reveals a complex interplay between green policies and key economic variables such as inflation, economic welfare, and the labor market. This study demonstrated that while green policies are essential for combating climate change and promoting environmental sustainability, they also bring significant economic consequences that must be carefully managed.

Impact on Inflation and Economic Welfare: The Green Deal, particularly through its Fit-for-55 package, has driven a linear increase in fossil energy prices, which in turn has raised production costs, reduced output, and diminished real wages. These inflationary effects are exacerbated by the expansive fiscal and monetary policies accompanying green initiatives. The implementation of green taxes, subsidies for renewable energy, and stringent environmental regulations raise production costs, ultimately passing on these costs to consumers through higher prices for goods and services.

Although the goal of these policies is to foster future well-being by mitigating climate risk, in the short term, they can result in decreased consumption, negatively impacting economic welfare, especially for lower-income households. The reallocation of resources towards green investments can reduce immediate consumption, undermining short-term economic welfare.

Labor Market Disruptions and Economic Efficiency: Green growth policies also have the potential to significantly disrupt labor markets. The transition to green jobs may not be immediate or smooth, causing job losses in traditional energy sectors and increasing unemployment in regions dependent on fossil fuel industries. These structural changes can lead to greater reliance on social welfare programs and periods of economic instability.

Moreover, while green tax reforms can potentially improve environmental quality and economic efficiency, they can also impose additional tax burdens on businesses, reducing their competitiveness and slowing economic growth. Taxes and regulatory burdens can stifle innovation and investment, exacerbating economic slowdowns.

Sectoral Imbalances and Investment Risks: The Green Deal’s focus on climate and energy policy can create sectoral imbalances, with overinvestment in green sectors and underinvestment in other crucial areas of the economy. This can lead to inefficiencies and potential economic stagnation. Additionally, the transition to green investments carries inherent risks, as the economic benefits of green fiscal policies may not materialize as expected, leading to potential financial instability.

Critique from the Austrian School of Economics: From the perspective of the Austrian School of Economics, extensive government intervention and central planning inherent in the Green Deal are seen as inefficient. Austrian economics emphasizes the importance of the free market for efficient resource allocation and innovation through competition. Government intervention, by distorting price signals and restricting entrepreneurial freedom, can lead to inefficient resource allocation and reduced market adaptability.

Recommendations: To mitigate the adverse effects of greenflation and maximize the benefits of green policies, it is crucial to adopt a balanced approach that considers both environmental goals and economic stability. The following recommendations can help achieve this balance:

Adjusted Monetary and Fiscal Policies: Develop monetary policies that carefully manage inflation resulting from green transition costs and adjust fiscal policies to minimize additional burdens on businesses.

Support for Labor Transition: Implement training and support programs for displaced workers, facilitating their transition to green jobs and minimizing labor market impacts.

Balanced Investments: Ensure a balanced distribution of investments between green sectors and other essential areas to avoid economic imbalances.

Fostering Unrestricted Innovation: Allow the market to drive innovation and efficiency by reducing interventions that distort prices and limit entrepreneurial freedom.

In conclusion, the Green Deal represents an ambitious effort to address climate challenges, but it must be implemented with a clear understanding of its economic implications and a careful strategy to balance environmental goals with economic stability and welfare.