1. Introduction

Since China embarked on reform and opened up, its economy has experienced rapid growth and attained significant achievements. Nevertheless, with the fast growth of the economy, China’s overall energy consumption has surged, escalating from 570 million tons of standard coal in 1978 to 4.98 billion tons by 2020, marking a 773.7% increase. This surge has positioned China as the world’s foremost energy consumer. The prevailing economic model, characterized by elevated energy consumption, emissions, and pollution, not only diminishes energy efficiency but also inflicts severe ecological harm. The worsening of the ecological environment has heightened the conflict between economic progress and environmental conservation, limiting China’s economy’s sustainable development [

1]. Currently, China’s economy has transitioned into a phase characterized by high-quality growth [

2]. Therefore, we need to transform the economic growth model that relies heavily on energy consumption. Developing effective environmental policies that foster carbon emission reduction, mitigate pollution, and expedite the shift towards a green economic model has become a pressing priority. In response, the Chinese government has innovatively introduced the ECRTP as a pivotal environmental management initiative. This policy aims to catalyze the green evolution of industries and advance China’s economy towards sustainable, high-quality development using market-driven strategies.

The core of the ECRTP involves the government controlling the total regional energy consumption and granting enterprises quantitative energy right trading quotas based on regional energy endowment and energy-saving potential. These enterprises are then allowed to buy or sell energy use indicators in the energy right trading market, thereby utilizing the market mechanism to reduce energy consumption. In September 2016, the National Development and Reform Commission introduced ECRTP in the provinces of Zhejiang, Fujian, Henan, and Sichuan. Each province actively participated in the system, clarifying the scope of the trading pilot, enhancing the platform’s construction, and approving the pricing mechanism. At the end of 2021, the State Council proposed an extension of the ECRTP, with the aim of strengthening its integration and connection with the trading of carbon emission rights. In 2022, the report of the Twentieth Party Congress highlighted the need to improve total energy consumption and intensity regulation. Thus, China persists in promoting the establishment of an environmental and energy governance system and remains committed to combining market-oriented and energy consumption “dual control” goals, and is implementing the pilot policy of energy rights trading to enhance its market-oriented environmental regulatory policies.

Although the existing scholars have conducted extensive research on the environmental, economic, and social impacts of the ECRTP, certain limitations remain apparent. Firstly, discussions about the impacts of the ECRTP focus primarily on the city level. For example, research indicates that the ECRTP has the potential to improve urban green development efficiency and urban innovation quality [

2,

3]. However, there is a lack of attention to the implementation effects at the enterprise level. The internal logic of the ECRTP is consistent with high-quality enterprise development requirements. Enterprises, as important participants in economic activities, have shifted their development goals from a singular pursuit of profit to a comprehensive consideration of sustainable development in the social, environmental, and governance domains. Limited research also suggests that the ECRTP could enhance corporate green technology innovation [

4] and environmental performance [

5]. An energy rights trading policy encourages environmental subjects to make behavioral decisions through market mechanisms. This not only prompts enterprises to decrease energy consumption and enhance resource allocation efficiency from the source and process control, but also significantly influences their production and operation, capital operation, and technological advancement. This, in turn, is conducive to the coordination of enterprises’ social, environmental, and governance [

6]. Thus, it is necessary to examine how the ECRTP affects enterprises’ ESG performance. Secondly, the majority of empirical research on the ECRTP concentrates on provincial-level data, ignoring studies conducted at the enterprise level using data from listed companies [

4]. Empirical support for whether the ECRTP improves enterprises’ ESG performance remains insufficient. To address these research gaps, in this study, the ECRTP serves as a natural experiment, analyzing empirical data from A-share-listed firms spanning 2006 to 2020. The research employs a difference-in-differences (DID) approach to investigate how ECRTP influences corporate ESG performance. This approach provides a reference for accurately assessing the policy’s economic effects and guiding policy reforms, thereby supporting green economic development.

The paper makes significant contributions in the following areas: First, this paper uses the ECRTP as a starting point to investigate the policy’s micro-governance impact from the special perspective of corporate ESG performance. This research enhances our understanding of the economic consequences of the ECRTP. Secondly, the majority of existing research on the ECRTP focuses on provincial and city levels. However, such large regional spans can lead to biases in policy evaluation outcomes. Thus, analyzing corporate responses to the ECRTP and investigating its impact on corporate ESG performance offers a more accurate assessment. Thirdly, this paper examines the mechanisms through which the ECRTP affects corporate ESG performance by focusing on green technology innovation and executive green perception. It also conducts a thorough analysis of the heterogeneity in terms of environmental concern, whether the enterprise is heavily polluting, and whether it is located in a coastal or non-coastal region. This enriches the understanding of how the ECRTP influences corporate ESG performance. It provides policy references for improving the ECRTPs implementation strategy and enhancing enterprises’ ESG performance.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Energy-Consuming Right Trading Policy

To maximize the effectiveness of market mechanisms and promote the concentration of energy resources in high-quality enterprises and industries, the government has proposed market-driven energy rights trading. In 2015, the State Council issued the “Overall Plan for Ecological Civilization System Reform”, introducing the concept of the ECRTP. In 2016, the National Development and Reform Commission released the “Pilot Scheme for Paid Use and Trading of Energy Rights”, which decided to pilot the energy-consuming right trading policy in Zhejiang, Fujian, Henan, and Sichuan provinces in 2017 based on local development conditions and the national total energy consumption targets. Specifically, the pilot regions established the initial energy consumption quotas for each energy-consuming unit based on local development conditions and national energy consumption targets. The government then conducted energy-consuming right trading through sales to enterprises, repurchases from enterprises, and inter-enterprise transactions, thereby guiding the rational flow and efficient allocation of energy resources. The scope of the ECRTP is more extensive than the previously implemented carbon emissions trading policy in China, which primarily affected heavily polluting industries. Furthermore, the ECRTP primarily focuses on implementing control measures at the source, aiming to determine energy rights indicators scientifically and reasonably in advance, optimize the energy structure of pilot areas’ enterprises, boost energy efficiency, and control total energy consumption.

Currently, research on the ECRTP mainly focuses on its energy-saving effects and economic impacts. Specifically, at the macro level, studies have indicated that the ECRTP not only enhances the efficiency of urban green development and the quality of urban innovation [

2,

3], but also promotes GDP growth [

6]. Additionally, research has confirmed that the ECRTP can reduce carbon intensity, energy intensity, and total energy consumption [

7,

8,

9]. At the micro level, Shao and Liu point out that the ECRTP promotes green technological innovation in enterprises [

4]. Shen et al. confirm that the ECRTP can enhance the environmental performance of enterprises [

5].

An examination of the current body of literature indicates that there is still potential for enhancing research on the ECRTP. The majority of studies have concentrated on analyzing the impacts of the ECRTP at the macro level. These studies overlooked the crucial role of enterprise. The ECRTP directly targets enterprises in the pilot regions. Thus, it holds greater scientific and practical significance to test the effect of the ECRTP from an “enterprise perspective”. This study addresses existing gaps by centering the research sample on the enterprise level.

2.2. Corporate ESG Performance

ESG performance mainly measures the company’s level of environmental protection, social responsibility, and governance [

10]. On the one hand, companies need to take on environmental and social responsibilities while pursuing their own profits. On the other hand, to attain sustainable development, it is necessary to continuously improve development strategies and governance structures to enhance corporate governance to the greatest extent possible [

11]. Therefore, enhancing ESG performance is essential for the firms’ sustainable growth.

With the increasing significance of sustainable developments, an expanding body of literature has been investigating the factors influencing the ESG performance of corporation. Among these, the influence of environmental regulations on ESG performance has become a hot topic in theoretical research [

10]. However, current research primarily concentrates on examining the impact mechanisms of command-and-control environmental regulations. Wang et al., for example, found that central environmental inspections can enhance the ESG performance of corporations by strengthening government environmental supervision [

12]. Research on environmental regulations from the perspective of market incentives remains insufficient. In particular, we have not yet addressed the impact of ECRTP, one of the market-driven environmental regulation policy tools, on corporate ESG performance. Some scholars have suggested in sporadic studies that the ECRTP could strengthen corporate environmental performance [

5]. While these studies examine certain facets of ESG performance, they do not comprehensively analyze how the ECRTP affects ESG performance as a whole. Therefore, this research aims to analyze the influence of the ECRTP on corporate ESG through the new lens of market-driven environmental regulation.

2.3. Energy-Consuming Right Trading Policy and ESG Performance

The ECRTP, characterized by market-oriented environmental regulation, is expected to enhance enterprises’ ESG performance. The ECRTP aims to internalize enterprises’ external energy costs. Simultaneously, it seeks to use market mechanisms to drive energy allocation efficiency to reach Pareto optimality, achieving energy conservation, emission reduction, and environmental improvement at the lowest transaction cost [

4]. Although this policy may increase environmental compliance costs for enterprises, according to the Porter Hypothesis, the ECRTP could also stimulate technological innovation, leading to economic compensation in terms of energy savings, product quality, and production efficiency [

13], thereby achieving a win–win situation for both economic performance and ESG performance.

Firstly, the ECRTP could greatly enhance environmental performance. The energy rights trading policy incentivizes enterprises to achieve energy-saving goals, reduce pollutant emissions, improve production efficiency and product quality, and accelerate industrial upgrading by restricting total energy consumption quotas [

8]. Consequently, enterprises are motivated to allocate more resources to environmental management. Meanwhile, in China, the ECRTP operation is an important top-level design and systematic plan. Local governments actively encourage participants in energy trading to engage in green technological innovations, eliminate outdated production capacities, and improve resource efficiency to enhance local environmental performance [

5]. They also provide support to enterprises in terms of finance, taxation, and other aspects, increasing their excess profits and reducing their marginal costs of emissions reduction and pollution control [

14]. This process encourages companies to actively take on environmental responsibilities.

Secondly, the ECRTP could greatly improve social performance. When the market value is low or the financial risk is high, enterprises are more inclined to invest in projects with higher liquidity and short-term returns. Due to the long investment cycles and substantial capital requirements of environmental governance, enterprises are reluctant to actively invest in environmental governance [

15]. On the one hand, the introduction of the ECRTP has increased the attention of the capital market and the general public to the energy trading market. According to the signaling theory, a company’s participation in energy rights trading can be seen as a positive green signal that is perceived by the market. As a result, the company will have greater motivation to invest in environmental governance [

16]. When enterprises develop or introduce new processes and production equipment, they may create new green employment opportunities, optimize employees’ working environments, and increase corporate employment levels [

17]. On the other hand, with the increasing attention from the capital market and the general public to the ECRTP, enterprises participating in energy rights trading will face stricter supervision and control. In order to enhance their “discourse power” in financing, increase their valuation level, or reduce financial risks, enterprises will actively carry out green technological innovation and adopt greener production methods, thereby promoting the improvement of product quality and creating green value for consumers [

18]. Ultimately, this dynamic balance enables companies to achieve a harmonious coexistence between their self-interest and social responsibility.

Finally, the ECRTP can significantly improve governance performance. Participating in energy-consuming trading could effectively enhance the ability of enterprise operators to capture market information and standardize their investment behavior [

19]. Simultaneously, enterprises involved in energy rights trading will attract more attention. Stakeholders such as the government, potential investors, banks, and the general public can provide support or exert influence on corporate governance from different perspectives [

16]. The investment information provided by investors enables corporate managers to promptly understand market changes, effectively respond to or avoid operational risks, constrain managerial opportunistic behavior, and enhance the company’s risk control management [

20]. This, in turn, helps to protect investors’ rights and interests. To mitigate the risks arising from internal and external information asymmetry, companies actively fulfill their external governance responsibilities [

21]. Companies participating in energy rights trading will experience closer information sharing and collaboration between the management and the board of directors, leading to a more robust internal governance structure. Consequently, this enhances the level of ESG information disclosure, decreases information asymmetry between companies and stakeholders, and improves corporate governance performance [

22]. Based on the analysis provided above, we put forth the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1. The energy-consuming right trading policy can improve corporate ESG performance.

2.4. The Mediating Role of Green Technology Innovation

ECRTP could enhance firms’ ESG performance by promoting green technology innovation. On the one hand, under the soft constraints of energy consumption policies, firms will adopt strategies such as enhancing technological innovation capabilities and upgrading and transforming their operations based on their cost-effectiveness of energy consumption [

23]. If the cost of innovation can offset regulatory costs and improve market profitability, firms will choose to innovate. Therefore, energy rights policies will guide firms to adopt innovative technologies to save energy and accelerate industrial upgrading. Existing research also suggests that the ECRTP can trigger green technology innovation [

4]. On the other hand, through green technology innovation, firms could control pollutant emissions, provide environmentally friendly products to the public, reduce energy consumption, and thereby improve their environmental, social responsibility, and governance performance. Existing research also supports the positive influence of green technology innovation on firms’ ESG performance [

24]. Based on the above analysis, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2. Green technology innovation plays a mediating role between energy-consuming right trading policy and corporate ESG performance.

2.5. The Mediating Role of Executive Green Perceptions

ECRTP could improve firms’ ESG performance by encouraging executive green perceptions. ECRTP uses market mechanisms to provide direct economic incentives for energy conservation and emission reduction [

25]. This economic incentive mechanism encourages executives to prioritize energy management and green technologies to reduce operational costs and enhance economic benefits [

26]. Strict regulatory and evaluation mechanisms often accompany ECRTP [

27], prompting executives to focus on green development and enhance their green awareness to ensure compliance. Furthermore, executives who have a deep understanding of ecological and environmental issues actively seek out additional information on green development, consistently improve their understanding of green practices, and implement proactive measures for energy conservation [

28]. Executives with strong green perceptions also emphasize environmental protection in their products and processes, promoting corporate environmental information disclosure [

29]. They could promote sustainable development concepts in the organization, thereby improving enterprises’ ESG performance. From the analysis above, we posit the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3. Executive green perceptions play a mediating role between energy-consuming right trading policy and corporate ESG performance.

6. Conclusion and Insights

6.1. Research Conclusions

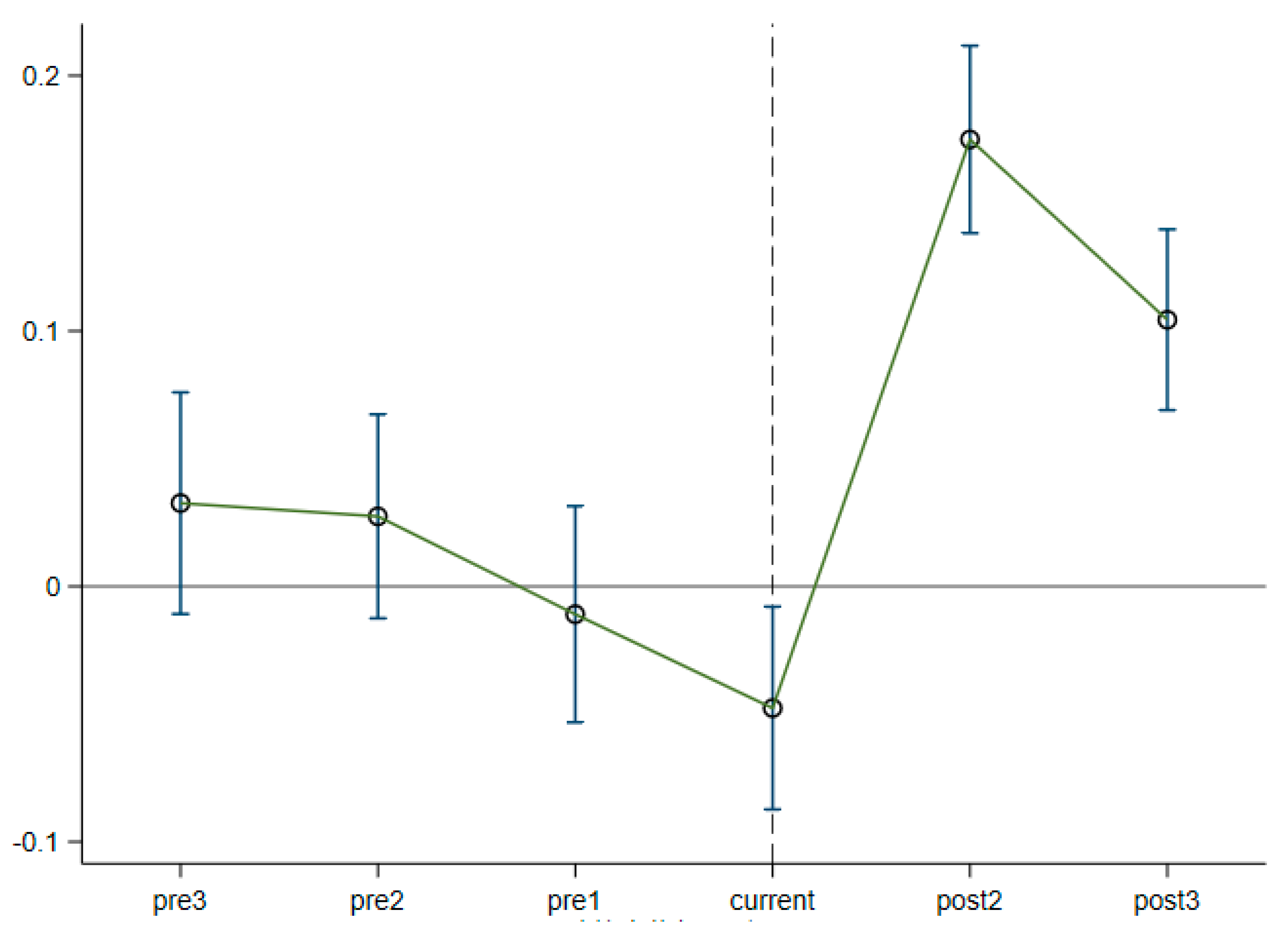

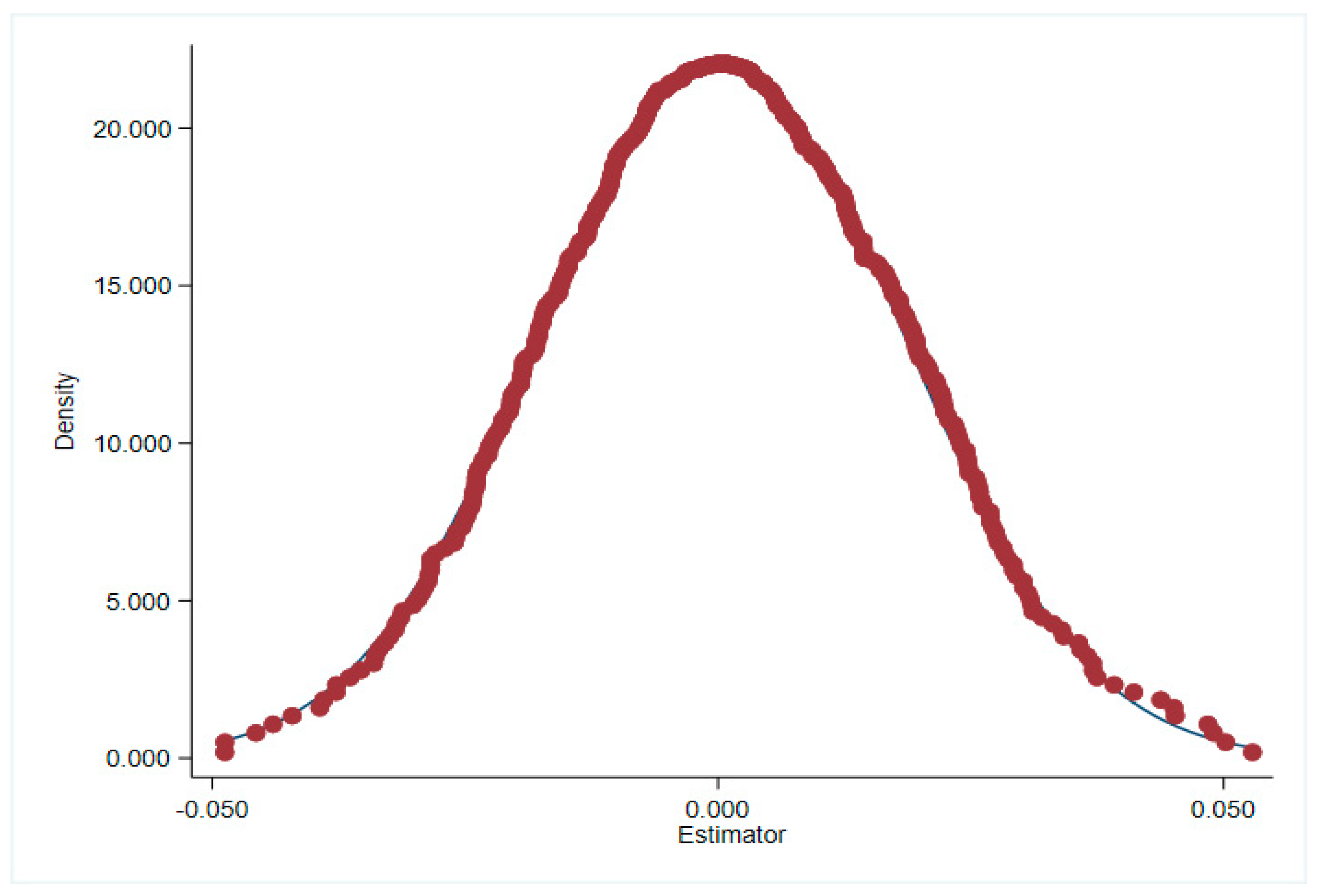

ECRTP encourages companies to improve efficiency and reduce emissions through market mechanisms, helping to leverage ESG-related investments and improve their ESG performance. Currently, limited research has incorporated ECRTP and enterprise ESG performance into a unified analytical framework. Therefore, with the launch of the ECRTPs pilot in China in 2017, our study aims to investigate the following crucial issue: How does the ECRTP impact ESG performance? To address this question, this study examines panel data from 1463 Chinese listed industrial firms spanning 2006 to 2021. We utilize a DID model to investigate the influence of ECRTP on firms’ ESG performance using a quasi-natural experiment. The primary research findings are outlined below: (1) The ECRTP may greatly enhance the ESG performance of corporations. Several tests of robustness have shown that these results are still valid. These include the parallel trend test, propensity score matching, lagged one-period treatment, placebo test, replacement of explained variables, and excluding interference from other policies. (2) The impact mechanism analysis reveals that the ECRTP can promote corporations’ ESG performance by promoting corporate green technology innovation and executive green perception. (3) Heterogeneity analysis demonstrates that the ECRTP significantly enhances ESG performance for enterprises situated in provinces with high public environmental concern, whereas this effect is not significant for enterprises located in provinces with low public environmental concern. In terms of the firms’ regional attribute characteristics, the policy has a significant influence on enhancing ESG performance among enterprises in coastal regions, yet it lacks significance in non-coastal areas. When it comes to the pollution characteristics of firms, implementing ECRTP has a big impact on the ESG performance of firms that do not pollute a lot, but not so much on firms that do pollute a lot. This study enriches the literature on evaluating the effects of ECRTP, offering insights into improving its design and facilitating the realization of dual-control targets for energy consumption.

6.2. Policy Recommendations

ECRTP, a market-based tool, can effectively manage energy consumption through supply-demand relationships and pricing mechanisms. This market mechanism can incentivize companies to adopt more environmentally friendly practices, thereby enhancing their ESG performance, gaining competitive advantages, and earning social recognition [

36]. However, relying solely on market mechanisms may not entirely solve all issues. In certain cases, government intervention with administrative tools is necessary to guide and regulate market behavior, ensuring fair competition and the achievement of environmental protection goals [

37]. By setting appropriate policies and regulations, the government can provide incentives or impose penalties to encourage companies to actively participate in energy rights trading and comply with relevant ESG guidelines. Therefore, policy design should balance the coordinated use of market mechanisms and administrative tools to effectively advance the successful implementation of ECRTP.

First, the government ought to align with the market-oriented reform trend and gradually extend the pilot program’s scope, drawing on successful policy implementations. Simultaneously, the government should leverage the market-oriented characteristics of the ECRTP to encourage the enterprise’s autonomous energy conservation efforts. We will increase the quota of ECRTP appropriately as an incentive for enterprises that have invested heavily in R&D to modernize their manufacturing technology and equipment. This will allow them to sell excess indicators on the trading market, therefore obtaining further financial assistance. At the same time, it is imperative to establish a robust penalty system, bolster oversight of local regulatory bodies, and enhance the development of relevant legal statutes and regulations related to ECRTP so as to provide an effective guarantee for ECRTP.

Second, we should develop differentiated ECRTP, focusing on the energy-consuming characteristics of different enterprises. We should determine a reasonable initial energy-use quota for enterprises, taking into account their energy-saving potential, to mitigate the pressure on innovation, research, and development due to rising energy costs. Coastal areas should leverage their talent and resources, overcome obstacles to green innovation, advocate for industry restructuring, and devise innovative strategies to enhance the effectiveness of energy-use-right policies. Non-coastal areas, on the other hand, ought to speed up the utilization of clean energy, facilitate the transfer of advanced technologies and industries between regions, and improve the laws and regulations governing energy use to expedite the attainment of the “dual-carbon” goal.

Third, the government should enhance green technology innovation within enterprises and fortify the green awareness of enterprise executives. The government should increase the introduction of foreign capital and talent while simultaneously providing enterprises with financial support in the form of subsidies and finance. Additionally, it should encourage high-quality talent to support enterprises’ green technology innovation, thereby enhancing both the quantity and quality of enterprises’ green innovation.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

This research does have certain limitations. First, the impact of ECRTP on the company’s ESG performance may vary between short-term and long-term outcomes. In the short term, companies might face certain costs and pressures. However, as policy measures and management systems gradually improve, there will be significant enhancements in environmental performance, social image, and governance levels in the long run, ultimately maximizing the overall benefits. Therefore, future research could consider extending the analysis to nonlinear models, and policymakers and practitioners should also be mindful of these nonlinear impacts when designing and implementing policies. Second, this study’s sample consists of companies listed on the A-share market of the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges, excluding unlisted companies. As a result, the sample’s coverage and the research findings’ applicability remain somewhat limited. Future research could enlarge the sample size further to investigate the corresponding situations for non-listed firms. Third, because of data limitations, this study only updates the sample up to 2019. Examining the sustainability of the ECRTPs impact on company ESG performance remains a challenge. Future research should aim to incorporate more recent data to validate these effects over a longer period.