Abstract

As the main source of energy supply and carbon emissions, the oil and gas industry has entered the comprehensive low-carbon transition stage driven by various factors. Since different oil companies possess distinct understandings of transition paths, the effect of low carbon transition varies greatly. Obviously, it is necessary to evaluate the performance of low-carbon transitions within the oil and gas industry. Therefore, in this paper, 10 major international oil companies are taken as examples, and a super-efficiency slack-based measurement (super-SBM) model is applied in the present study to analyze the efficiency of low-carbon transitions. Furthermore, the logarithmic mean Divisia index (LMDI) is used to decompose the driving factors of carbon emissions and analyze their impact on the low-carbon transition of international oil companies. The obtained results reveal that although major oil companies have taken different measures in low-carbon transition and achieved a year-on-year reduction in carbon emissions, from the perspective of the efficiency of the entire production and operation process, these oil companies are inefficient in carbon emissions and need to adopt more effective low-carbon transition strategies; Moreover, after the further decomposition of the carbon emission driving factors of the 10 companies, it is found that improving the energy consumption intensity and development level of oil companies can effectively improve the effect of low-carbon transition of international oil companies. Drawing on the above findings, this paper puts forward suggestions for the low-carbon transition of energy companies, thus providing theoretical support and guidance for energy companies in different countries to implement low-carbon transition and green development strategies.

1. Introduction

The development environment of the oil and gas industry has changed dramatically in recent years. The Paris Agreement calls for global carbon neutrality in the second half of this century and calls on parties to propose long-term low-emission development strategies based on common but differentiated responsibilities and capabilities, taking into account their own national circumstances [1]. The United States, the European Union, Japan and South Korea have announced that they will achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. For example, the US passed the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022, European countries have passed legislation to promote net-zero emissions and the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism came into effect in May 2023. Moreover, since the Ukraine crisis has profoundly reshaped the global energy pattern, Europe has strengthened its determination to develop new energy in the long run to rid itself of its dependence on Russian energy. For major oil and gas companies worldwide, especially those international oil companies, in the context of increasingly stringent requirements to reduce carbon emissions from governments, environmental organizations and consumers, they have entered a new stage of low-carbon transition [2]. Not only do they formulate emission reduction targets, but also make significant adjustments in the setting of transition goals, the scale of low-carbon business investment, the development planning of oil and gas businesses, as well as supporting organizational management models and new business operation models [3]. At present, different types of oil companies have significantly different understandings of transition, so the effect and depth of transition have shown great differences. Therefore, it is of great practical significance to explore the greenhouse gas emissions, low-carbon transition efficiency and analyze the influence direction and degree of related driving factors of international major oil companies.

In fact, international oil companies (IOCs) typically reduce carbon emission intensity and total emissions through the low-carbon restructuring of upstream operations and implementing various measures [4]. On the one hand, IOCs increase the proportion of natural gas in total oil and gas production, conduct large-scale divestment of non-core and high-carbon upstream assets, and reduce capital expenditure in upstream operations. On the other hand, they reduce carbon emissions by intensifying technological research and development, improving energy efficiency in the oil and gas production process, reducing conventional combustion, utilizing clean electricity to enhance the cleanliness of their own energy consumption for production, employing carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology, accelerating the transition from traditional refineries to biomass refineries, and strengthening their chemical business operations [5]. Moreover, IOCs have increased their investment scale in low-carbon businesses. By selectively deploying new businesses that align with their own strengths, they aim to achieve synergistic development between low-carbon and traditional oil and gas businesses, as well as maximize company benefits. For example, in the investment portfolios of low-carbon business, European oil companies have extensively ventured into new areas like renewable energy power generation, battery energy storage and mobility, natural gas and electricity transmission and distribution, willing to take on greater transformation risks. In contrast, American oil companies prefer to concentrate their low-carbon investments in businesses like biofuels, CCS, and hydrogen. These businesses are characterized by lower transformation risks and secured expected investment returns.

Therefore, different types of national oil companies vary greatly in energy transition intensity and paths. If the resource endowment is poor and the national economy is not very dependent on domestic oil companies, the government may propose “carbon peaking and carbon neutrality goals”, such as China’s NOC which has formulated the most active energy transition goals and implementation plans. Countries with resource endowment advantages and the national economy is more dependent on domestic oil companies, they usually adhere to the development of traditional advantageous resources rather than setting up net-zero emission goals, such as Saudi Aramco, Rosneft Oil, Gazprom, Petrobras, etc., which still focus on the development of oil and gas resources, but propose a reduction in the level of carbon emissions and exploration of the development of new energy businesses with resource advantages. Considering the environmental factors and the increase in the influence of future investor sentiment, Saudi Aramco, Rosneft Oil, etc., have formulated carbon neutrality plans, see Table 1 for the details of low-carbon transition for oil companies.

Table 1.

Low-carbon transition path of international oil companies.

Besides the actions the oil companies have taken in practice, much has been performed for the low-carbon transition of international oil companies in the academic field. Through the analysis of the low-carbon business strategies and investments of seven international oil companies, including bp and TotalEnergies, Tianjiao et al. [6] predicted the low-carbon business strategies of the companies under different scenarios in the future, and put forward suggestions for the low-carbon energy transformation and development of Chinese oil companies. Fattouh et al. [7] focused more on the impact of the energy transition on oil companies and oil-exporting countries. Lu et al. [8] summarized the low-carbon transition actions of the nine major oil and gas companies.

At the same time, global businesses have foreseen the physical, regulatory, and brand equity risks posed by the challenges of climate change. As for the evaluation of specific low-carbon strategies, a lack of research is shown evaluating the effects of low-carbon transition, and scholars have focused more on exploring the path of low-carbon transition and proposing the economic impact of relevant strategies on the country and companies. Choudhary et al. [9] prepared a comprehensive GHG footprint plan in response to the climate change challenge and provided recommendations for the Oil and Natural Gas Corporation, a Fortune 500 and Indian oil corporation. Li et al. [10] proposed measures such as pipeline sharing and developed a method for estimating the capacity of biofuel transportation pipelines. Sun et al. [11] analyzed the impact of taxation on energy conservation and emission reductions. Li et al. [12] proposed the construction of a CCS preparation center, which significantly reduced the overall cost of building an integrated CCS system. Turk et al. [13] analyzed the feasibility of offsetting conventional gas carbon emissions with the shale gas industry in the UK from a national perspective. Stewart and Stewart and Haszeldine [14] studied the feasibility and effectiveness of offshore CO2 enhanced oil recovery (CO2EOR) on a technical level. Soltanieh et al. [15] considered the development of the necessary regulatory policies and measures at the national level by assessing the economic and technical factors affecting the implementation or postponement of gas projects. Combining the copula GARCH model with Monte Carlo simulation, Quintino et al. [16] argued that the success of low-carbon product switching depends on gasoline prices and the way an aromatics plant is constructed, and that the construction method of aromatic plants, and that product switching cannot achieve the expected reduction in consolidated refined margin volatility. Some scholars have also focused on the transition paths of oil companies. Lu, Guo, and Zhang [8] conducted a case analysis of the low-carbon emission transition practices of several large oil and gas companies, focusing on the transition goals, investment and action, opportunities and challenges. Moreover, some scholars have completed research on the driving factors of specific low-carbon effects. Chua and Oh [17] reviewed the renewable energy and energy efficiency implemented by Petronas from 1974 to 2010 from a policy perspective. From a city’s viewpoint, Cheshmehzangi et al. [18] studied the impact and long-term benefits of international cooperation and international partners in the process of building international low-carbon city development. Tan et al. [19] established an indicator framework for low-carbon city evaluations from the perspectives of economy, energy model, society and life, carbon and environment, urban mobility, solid waste and water, and applied it to 10 global cities for ranking. Taking the Chinese manufacturing companies as an example, Li et al. [20] examined the mediating role of green core competitiveness on the relationship between low-carbon technological innovation and companies’ performance, and concluded that company size has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between low-carbon technological innovation and companies’ performance. Sun et al. [21] demonstrated that the carbon intensity of a company is negatively related to its financial performance by taking Chinese listed companies involved in the low-carbon industry from 2010 to 2018 as a sample. Focusing on Kazakhstan oil companies, Alfiya E. Tasmukhanova [22] established an oil company transformation algorithm to obtain the distribution process of power, roles, and responsibilities. Sarrakh et al. [23] used qualitative methods to collect and analyze 24 respondents from eight organizations, thus revealing the challenges in the transition process. Zhang Haixia et al. [24] evaluated the sustained competitiveness of state-owned oil companies by using the entropy weighting method to analyze the sustained competitiveness of three major Chinese state-owned oil companies against Exxon Mobil from 2014 to 2018.

Although there has been a lot of research on the low-carbon transition of oil companies, few studies have empirically analyzed the effects of their transition. As the evaluation of performance on low-carbon transition plays a pivotal role in the energy industry, this paper aims to assess and compare the effects of low-carbon transition strategies in different large-scale IOCs around the world. By doing so, this paper attempts to summarize the useful experience of energy transition in IOCs and find the bottleneck problems encountered during the transition process, proposing practical suggestions and implications for these IOCs and even the entire energy industry. Therefore, an integrated assessment framework is established by combining the super-SBM model and the LMDI model to show the results of low-carbon transition and discuss the underlying driving factors. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: in Section 2 (Materials and Methods), the methods we utilized are explained; then, the cases are introduced and analyzed in Section 3, the calculation results and further discussion are also displayed in this section; based on these results, we summarize the suggestions and implications for IOCs in Section 4; finally, we conclude this paper in Section 5.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Efficient of Oil Companies Based on Super SBM

The super-slack-based measurement model (SBM) is an improved method based on the data envelop analysis (DEA) model. It can calculate the efficiency of the production activities of the research object in the presence of multiple inputs and outputs. Compared to traditional DEA, it can handle the slack variables and provide a more comprehensive efficiency analysis. There are several advantages of the super-SBM models: (1) SBM models can simultaneously consider the imbalance between inputs and outputs, making them more comprehensive in the efficiency evaluation; (2) the SBM models s are compatible with different types and sizes of data, thus, they are more flexibly applicable in diverse decision-making contexts; (3) the SBM models offer a more precise assessment of efficiency since they consider the slacks from a non-radical perspective; (4) the SBM models can help decision-makers identify reasons and set specific goals for efficiency improvements, so that they provide practical guidance. The SBM models have been widely applied to educational and medical institutions, finance, manufacturing and the energy industry. Therefore, this study adopts a non-radial, non-angle SBM model to measure the efficiency of oil companies in the process of low-carbon transition.

Assume there are n decision-making units, , representing the different oil companies in this paper. The aim of the super-SBM is to assess the efficiency of different DMUs; therefore, the model is employed to quantify the efficiency of large-scale international oil companies. Each decision-making unit contains input and output indicators, and the output indicators include desired and undesired outputs. Inputs indicate the resources consumed or invested by DMUs, including capital, labor, materials and energy, technology and knowledge, service, and so on. The desired outputs are generally performance or GDP, and undesired outputs can be negative externalities such as carbon emissions, pollution, etc. Therefore, assume that the input is k, the desired output is , the undesired output is . Expressed as a vector, , , represent the inputs, desired outputs, and undesired outputs of the DMUs, respectively. R represents a real number, so the set of production possibilities P is as follows:

where X and Y, representing the input and output, respectively, are the adjustment matrix. They symbolize the input and output along the efficient frontier.

The SBM model for undesirable output is as follows:

where , and . p is the slack variable for the input and output variables, is the efficiency value of DMU. and are the reference points of the decision variables. is the efficient frontier, and is the weight vector, in the SBM model, each DMU is composed of multiple inputs and outputs, and is used to assign weights to these inputs and outputs to assess the relative efficiency of each DMU.

Generally, the selection of input and output variables depends on the nature and industrial characteristics of the DMUs. Given the energy-intensive, capital-intensive and technology-intensive nature of oil companies, this paper uses energy consumption, investment in innovation, traditional businesses and number of employees as the input factors. The details can be found in Section 3.2 of this paper.

2.2. Driving Factors of Low-Carbon Transition Based on LMDI

The results of the super-SBM model can show the annual production efficiency of each oil company, establishing a objective and quantizable indicator to compare the achievement of GHG reduction of international oil companies. However, it is hard to show the underlying driving forces of the production efficiency. Therefore, this study further decomposes the input and output factors involved in the super-SBM model by the logarithmic mean Divisia index (LMDI) model. Japanese scholar, Yoichi Kaya, put forward the Kaya identity at an IPCC meeting, which was used to illustrate the relationship among carbon dioxide emissions and carbon intensity, energy intensity, per capita output, and population size. For further information, see Equation (4). By further decomposing the carbon emissions of oil companies (which is also the undesirable output in the SBM model), the driving forces for reducing GHG in the entire cycle of oil exploration, extraction, production, and sales can be more clearly understood, so that more effective management tools can be applied:

where C is the total greenhouse emissions; E is the energy consumption; G is the business revenue; and P is the number of employees.

Having the advantages of flexible variation and residual-free decomposition, researchers usually combine the Kaya identity with the LMDI decomposition method to further explore the driving factors and intensity of carbon emissions. Let F = C/E, U = E/G, N = G/P, then the further decomposition of the Kaya identity is carried out in the form of additive and multiplicative forms, where the purpose of the additive form is to investigate the impact of the increment of variables, and the multiplicative form is to investigate the impact of the rate of changes of variables.

The additive equation is as follows:

where

as weights, with , representing the relative contribution of each factor to the total change. That is, the weights here reflect the proportion of each factor in the overall change.

The product of the factors obtained by the multiplicative equation is as shown in Equation (7):

After further decomposition, the equation can be further transformed into:

The weight ω is as follows, indicating the relative ratio impact of each factor on the total change. The weights in the multiplicative equation reveal the impact on the overall change if a particular factor remains constant, while the other factors change as they actually do.

The other variables are calculated based on Equation (10):

In brief, this paper attempts to combine the super-SBM and Kaya identity to discuss the GHG reduction and low-carbon transition from different perspectives. The super-SBM is used to discuss the effect of GHG reduction from an input–output perspective; it can be regarded as an evaluation tool to assess the performance of oil companies in low-carbon transitions during the study period. Meanwhile, the additive and multiplicative forms of Kaya identity are used to describe the changes in GHG emission itself. Although the cannot be replaced by the addictive equation, the Kaya identity and its decomposed form aims to show more details about the underlying factors of GHG emissions in these large-scale oil companies. By decomposing the Kaya identity, this paper proposes more practical and specific suggestions for the decision-makers in international oil companies.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Case Study

To verify the effectiveness of the model proposed in this paper as well as to measure the effectiveness of the current low-carbon transition of international oil companies, this paper chose 10 large-scale international oil companies, including China National Petroleum Corporation, bp, Shell, etc., as the examples and collected the relevant data for calculation. These oil companies and their sizes (oil and gas equivalent reserves from 2020 to 2022) are displayed in Table 2. The reasons for choosing these oil companies are as follows. Firstly, the headquarters of these 10 international oil companies cover eight countries, including the US, China, and the UK, which can reflect the different attitudes and effects of various countries and regions on the low-carbon transition of traditional energy to a certain extent. Moreover, the size of these oil companies is huge, with subsidiaries and oil fields all over the world, and the oil and gas equivalent reserves of these 10 companies exceed 100 billion barrels in 2022. Therefore, analyzing the effects of the low-carbon transition of these oil companies can provide a reference for the low-carbon transition of traditional energy worldwide.

Table 2.

Oil companies and their oil and gas reserves from 2020 to 2022 (billion barrels).

3.2. Analysis and Evaluation of the Effect of Low-Carbon Transition

3.2.1. Indicator Selection and Data Sources for Super-SBM Model

This paper evaluates the low-carbon transition efficiency of 10 oil companies through the super-SBM model. Energy consumption, the proportion of upstream investment, and the number of company employees are chosen as input indicators. Specifically, the energy consumption indicator refers to the energy consumed by the company in all production, operation, and sales activities. Upstream investment represents the capital investment in oil and gas production and exploration, the proportion of it indicates the company’s investment in the oil production and exploration process, which also reflects the company’s future attention to traditional energy business. The number of employees demonstrates the company’s scale and labor input. In terms of output indicators, this paper takes the company’s annual operating income as the desired output indicator and GHG emissions as the non-desired output indicator. The selected indicators and data sources are shown in Table 3. Additionally, the 2015 Paris Agreement has prompted more traditional energy companies to pay attention to carbon emission reduction and to look for emission reduction technology and renewable energy investment opportunities. By 2020, several oil companies began to formally announce the implementation of low-carbon related strategies. Therefore, this paper chooses 2018–2022 as the study period to explore the efficiency of different oil companies before and after the low-carbon transition strategies, to further reflect the effectiveness of the low-carbon transition strategies implemented by these companies.

Table 3.

Input and output indicators and data sources.

3.2.2. Analysis of the Effects of Low-Carbon Transition

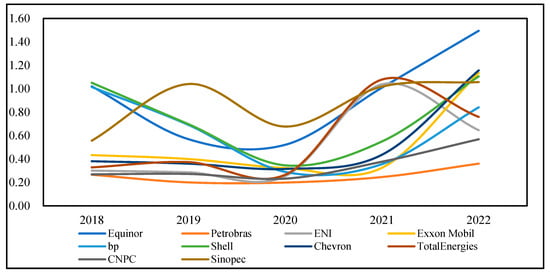

In this paper, the super-SBM model was constructed by MATLAB R2021a. The carbon emission efficiency of 10 international oil companies was calculated considering super-efficiency under the conditions of variable return to scale (VRS) and global DEA based on the indicators selected in Table 3. The results are shown in Table 4, and the trend of carbon emission efficiency of different oil companies is displayed in Figure 1. From Figure 1 and Table 4, it is found that the carbon emission efficiency of the 10 companies mostly shows an oscillating upward trend. Moreover, the reason for the fluctuation may be because these oil companies are still at the early stage of proposing carbon emission reduction targets, so each of them is still trying different strategies, which may not yet have formed a complete carbon emission reduction technological route and transformation program. However, the carbon emission efficiency of these 10 companies has increased to a certain extent after 2020, which reflects the effectiveness of carbon emission strategies to some extent. Calculating the growth rate of carbon emission efficiency of the 10 companies from 2018 to 2022, it can be seen that the carbon emission efficiency growth of ENI, Exxon Mobil, TotalEnergies, Chevron and CNPC, is more than 100%, with an average annual growth rate of more than 20%, which reflects that these companies have made great progress in the development of low-carbon transition.

Table 4.

Results of carbon emission efficiency of 10 international oil companies.

Figure 1.

Trends in carbon emission efficiency of 10 international oil companies.

According to the principle of the super-SBM model, the evaluated DMU is relatively efficient when the efficiency is greater than or equal to 1, while it is relatively ineffective when the efficiency value is less than 1. As can be seen from Table 4, the carbon emission efficiency of most oil companies is still not high, and only three companies, Equinor, bp, and Shell, are efficient in their carbon emissions at the beginning of the study period (2018). The other seven oil companies have an initial carbon emission efficiency of less than 1, which presents a relatively inefficient carbon emission efficiency. This result reveals that these oil companies is still far away from low-carbon transition and carbon neutrality, which requires further investment in capital and technology. With the gradual implementation of the low-carbon transition strategies of these oil companies, by 2022, five oil companies, namely Equinor, Exxon Mobil, Shell, Chevron, and Sinopec, have relatively effective carbon emission efficiencies, and although other companies’ carbon emission efficiency is still less than 1, it has already increased significantly compared to 2018.

Although the model under the super-SBM framework can assess the static efficiency well, it cannot measure the dynamic change in the efficiency of the decision-making units under the time series. Therefore, this paper introduces the Malmquist index (also called total factor productivity index) according to Xie and Li [25], which is used to indicate the dynamic trend of the efficiency of the DMUs under the time series. The results are shown in Table 5. A Malmquist index result greater than 1 indicates that the total factor productivity index of the oil company keeps growing from period t to t+1, A Malmquist index equal to 1 indicates that the total factor growth rate remains constant, and Malmquist index less than 1 indicates that the total factor productivity index decreases from period t to period t+1. The results in Table 5 demonstrate that the Malmquist index of almost all oil companies is less than 1 from 2018 to 2020, and the trend of the Malmquist index in Table 5 is basically consistent with the trend in the global oil futures price between 2018 and 2020. Therefore, this study suggests that the cause of the decline in the total factor productivity index may be because of the overall downturn in the traditional energy industry since 2018. In 2020, the Malmquist Index dropped to its lowest, possibly due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to a further decline in global oil demand and production. After the pandemic in 2020, 10 oil companies all experienced a significant increase in the Malmquist Index, which may be due to an increase in energy demand and production as a result of the global resumption of production after the pandemic. Moreover, 2020 served as the starting point for the majority of oil companies to adopt a low-carbon transition strategy or to issue a carbon-reducing target for their green growth strategies (including the adoption of more advanced extraction and exploration technologies, the development of diversified clean energy sources such as natural gas and photovoltaics, etc.) have also contributed to the increase in the Malmquist index to some extent.

Table 5.

Malmquist index of 10 international oil companies.

The Malmquist index reflects the changes in the total factor productivity of large oil companies. To further explore the specific driving factors of the entire carbon emission efficiency for different oil companies, this paper decomposes the Malmquist index and calculates the technical efficiency change (EC), the technical progress change (TC), scale efficiency change (SEC), and pure efficiency change (PEC) of the 10 oil companies, to explore the influence of the inputs of oil companies on the carbon emission efficiency.

According to Huang et al. [26], the Malmquist index can be decomposed into the product of EC and TC. Table 6 presents the EC and TC of 10 oil companies. Moreover, EC can be further decomposed into the product of PEC and SEC, and this decomposition reflects the impact of firm size and the resulting scale effect on the production and GHG emission efficiency of oil companies, as shown in Table 6. EC represents the comprehensive technical efficiency change, which is the catching-up trend of each DMU relative to the production frontier from period t to t + 1, that is, the degree of technical efficiency change from period t to period t + 1. TC refers to the movement of the production frontier from period t to t + 1, reflecting the degree of technical progress change in production. Therefore, an EC greater than 1 indicates an improvement in technical efficiency, i.e., the low-carbon transition strategy adopted by the decision-making unit is effective, while an EC less than 1 represents an inefficiency with the low-carbon transition strategy or the management strategies of international oil companies. As can be seen from Table 6, the EC of the 10 companies is basically greater than 1 or converging to 1 in each year from 2018 to 2022, revealing that the low-carbon transition and corporate management decisions of these companies are basically correct and effective. Although the EC of Equinor, bp and Shell is less than 1 in 2019, they have increased year by year over the following three years, reflecting the companies’ low-carbon transition and management strategy adjustments. Meanwhile, the TC of these companies basically shows an inverted U trend, and the magnitude of technological progress drops to its lowest in 2020, which may be affected by the decline in oil demand and production due to the global COVID-19 pandemic. However, it has increased significantly after 2020, attributed to the recovery of energy market after the epidemic and gradual implementation of the low-carbon transition strategy of the companies.

Table 6.

Technical efficiency change (EC) technical progress change (TC) of 10 oil companies.

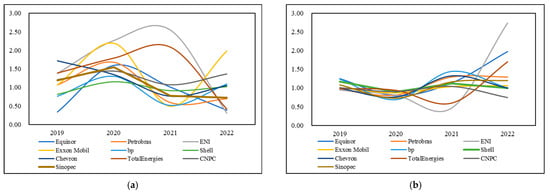

In this paper, EC is further decomposed into PEC and SEC to distinguish the impact of companies’ technical progress and scale effects. Table 7 displays the PEC and SEC of 10 international oil companies, and Figure 2 shows the trends of PEC and SEC, respectively. From Figure 2a, it is evident that, with the exceptions of ENI and TotalEnergies, the PEC of these international oil companies across different countries is largely consistent, which can be regarded as a sign that the technological advancements among these traditional petroleum-energy-based companies in oil exploration, extraction, and processing are broadly aligned. At the same time, changes in PEC reflect a shift in the technological focus of different companies to some extent, with more companies likely to focus their technological priorities on non-oil and non-gas businesses to facilitate a low-carbon transition. The trend of SEC movement is shown in Figure 2b. The trends of SEC movement for these international oil companies in different countries are basically the same until 2021, dropping to its lowest in 2020 (all oil companies have SEC values of less than 1 in 2020, see Table 6). However, since the beginning of 2021, the SEC has presented two divergent trends. The SEC of most oil companies began to recover in 2021, but ENI and TotalEnergies continued to decline in 2021 and increased significantly again in 2022, reflecting to some extent the differences in the management strategies of different oil companies after the epidemic.

Table 7.

Pure efficiency change (PEC) and scale efficiency change (SEC) of 10 oil companies.

Figure 2.

(a) The changing trends in PEC. (b) The changing trends in SEC.

3.3. Decomposition Calculation of Carbon Emission Driving Factors Based on the LMDI Model

The results in 3.2 explain the impact of factors such as the technical progress and scale of development of the oil companies themselves on their production and carbon emission efficiency. In fact, these oil companies are both sources of energy production and distribution. As large multinational corporations, they will also have a profound impact on local economic development. Therefore, this paper will further discuss the impact of factors such as the energy structure and business operations of the oil companies themselves in the production and operation process on the carbon emission efficiency based on the Kaya identity and the LMDI model in Section 3.3. According to Equation (4), this study decomposes the influencing factors related to carbon emissions (C) into energy structure intensity (F), energy consumption intensity (U), company per capita income (N) and company size (P). Energy structure intensity reflects the type and structure of energy used by the company in the whole process of production and sales, which can reveal the company’s use pattern of different types of energy and whether it adopts more clean energy that can reduce carbon emissions. Energy consumption intensity shows the company’s energy use efficiency through the calculation of energy consumption per unit of output value. The company’s per capita income reflects the level of development and profitability of the company, and the number of employees is collected to measure the company’s size.

Based on the additive decomposition presented in Equation (5), this paper assesses the impact of changes in these four factors on the amount of carbon emissions using a rolling base-period approach. The decomposition of the overall incremental carbon emissions of the 10 companies from 2018 to 2022 is shown in Table 8, and the specific carbon emission contributions of different companies are displayed in Table A1, Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4 in Appendix A. The results in Table 8 reveal that the total carbon emissions of the 10 international oil companies from 2018 to 2022 were decreasing year by year, but there are differences in the main contributing factors of carbon emissions each year. Combined with the results in Table 9, it can be found that in 2019, the factor that contributed the most to the reduction in carbon emissions of the 10 oil companies was the energy structure intensity, and the one that caused the most side effects was the energy consumption intensity. However, after 2020, the factor that contributes the most to the reduction in carbon is the energy consumption intensity, which indicates that there is a certain shift in the business development direction of these international oil companies. At the same time, the factor that caused the greatest burden on carbon emission reduction after 2020 is the level of economic development of companies, i.e., company per capita income, indicating that the per capita productivity of these large oil companies is still insufficient.

Table 8.

Decomposition results of the LMDI additive equation of 10 oil companies.

Table 9.

Contribution of carbon emission driving factors of 10 oil companies from 2018 to 2022.

The contribution of different factors to the carbon emission intensity of oil companies is further calculated as follows:

The results are shown in Table 9.

Based on the results of Table A1, Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4 in Appendix A, we analyzed the specific driving factors of different oil companies that lead to changes in carbon emissions. The 10 companies were divided into four categories, where (1) Equinor and TotalEnergies had the same changing trend of driving factors, with the largest contribution in the period 2019–2020 being the level of economic development of the company, and the largest contribution to carbon emissions in 2021–2022 being the energy consumption intensity; (2) Petrobras, ENI, and Exxon Mobil, showed the largest contribution to carbon emissions until 2021 as the level of development and profitability of the company, while in 2022, it was energy consumption intensity; (3) bp, Shell and Chevron, showed that the main contributing factors to carbon emission reductions in these three companies experienced a change from the energy consumption structure to corporate profitability, and then to energy consumption intensity; (4) CNPC and Sinopec showed that the factor that contributed most to low-carbon development was basically energy consumption intensity in both companies. Although the main driving factors for carbon emissions reduction varied from company to company in different years, it can be found that in 2020, the positive factors that had the greatest impact on the low-carbon development of oil companies were the level of business operations and profitability, reflecting the fact that under major external shocks (e.g., global economic and social crises, such as the coronavirus), the maintenance of business operations and profitability can better contribute to the low-carbon development. Moreover, in 2022, the factor that contributed most to the carbon efficiency of most oil companies (8 oil companies) was energy consumption intensity, suggesting that the main way for multinational oil wages to truly realize a low-carbon transition is to improve the efficiency of energy use per unit of output, and to use cleaner or less energy to create greater industrial output.

The LMDI decomposition by additive equation can reflect the impact of the amount of changes in different driving factors on the changes in carbon emissions, and the decomposition based on the multiplicative equation can better reveal the impact of the intensity of changes in different driving factors on the carbon emissions of oil companies. Therefore, based on the multiplicative equation decomposition, the driving factors of carbon emission are presented in Table 10 to reflect the impact of the relative changes of different driving factors on the carbon emissions of oil companies. The results in Table 10 reveal that changes in the energy consumption intensity and the level of company development have the greatest influence on the low-carbon development of multinational oil companies, which is similar to the decomposition results under the additive equation.

Table 10.

Decomposition results of LMDI multiplication equation of 10 oil companies.

4. Implications

From the analysis results in Section 3, although the major global multinational oil companies have begun to adopt different low-carbon emission reduction and green development strategies and their carbon emissions are decreasing year by year, the carbon emission efficiency of these oil companies is on the low side, and there is still a large space for development in the future. Through the decomposition of EC and TC Kaya identity, starting from energy consumption intensity, company economic development and profitability can better realize the low-carbon transition of multinational oil companies.

The energy consumption intensity of oil companies directly reflects the energy utilization efficiency in the exploration, production, and sales processes. The energy intensity can affect the investment strategy and competitiveness of oil companies. On one hand, in order to reduce energy intensity, oil companies need to invest in more efficient and cleaner energy technologies and solutions, such as renewable energy, carbon capture and storage technologies, etc. These investments not only help reduce the energy intensity of the company but also bring new business opportunities and sources of revenue. On the other hand, with the intensification in global energy market competition, the competitiveness of oil companies depends not only on the quality and price of their products but also on their energy intensity and environmental measures. By reducing energy intensity and adopting environmental measures, oil companies can enhance their competitiveness and gain more market share in the market.

The economic development and profitability of oil companies are also key factors affecting their transformation. Firstly, the financial condition is the foundation for oil companies to carry out energy transformation. Oil companies need to have sufficient funds to support their investment and operation in the energy transformation process. These investments may include R&D of cleaner energy technologies, purchasing and installing new equipment, training employees, changing operation modes, etc. If the financial condition of the oil company is not good, it may not be able to bear these costs and successfully carry out energy transformations. Secondly, the profitability of oil companies will influence their decision-making in the energy transformation process. If an oil company has strong profitability, it may have more confidence and capability to bear the risks and costs of energy transformation. At the same time, an oil company with strong profitability may also be more motivated to pursue new development opportunities, such as developing new clean energy projects, expanding into new markets, etc. Finally, the financial condition and profitability of oil companies will also affect their strategic choices in the energy transformation process. If the financial condition of an oil company is poor or its profitability is weak, it may pay more attention to short-term benefits and neglect long-term development. On the contrary, if an oil company has a good financial condition and strong profitability, it may focus more on long-term development and be willing to bear more risks and costs to promote energy transformation.

The impact of technological advancement on the low-carbon transformation of oil companies is multifaceted. Firstly, the advances in clean energy technologies have made clean energy more competitive and feasible. Oil companies can leverage these technologies to drive their own transformation towards low-carbon energy and reduce dependence on traditional petroleum products. Secondly, by utilizing advanced data analytics, artificial intelligence, and other technologies, oil companies can accurately monitor and manage energy consumption, optimize production processes, and reduce carbon emissions. Thirdly, the progress in automation and robotics technology allows oil companies to achieve more efficient production and operations, reducing labor costs, improving safety, and accelerating the transformation process. Lastly, digitalization and the Internet of Things (IoT) technology provide oil companies with better connectivity, coordination, and optimization capabilities for energy systems. Through digital platforms and IoT devices, oil companies can monitor and control energy facilities in real-time, optimize energy supply chains, and improve energy utilization efficiency.

Combined with the current transition measures taken by 10 oil companies, this paper proposes the following low-carbon green transition strategies for multinational oil companies:

- (1)

- Efficient and clean production processes of conventional oil and gas. As an important source of energy consumption for oil companies, the most effective ways to improve the efficiency of energy is to reduce carbon emissions from the exploration, extraction, processing and marketing of oil and other energy sources, thereby realizing decarbonization of the production process. On the production side, oil companies need to adopt more advanced and cleaner technologies for oil and gas production and processing, and increase the electrification level of energy production. In terms of carbon capture, large American oil companies are highly concerned about the decarbonization process of their core oil and gas business to maximize the capture and storage of carbon dioxide. Chevron plans to achieve its annual carbon capture and storage target of 25 million tons by 2030 and ExxonMobil is building a Houston CCS center with the goal of achieving 50 million tons of carbon capture and storage annually by 2030 and 100 million tons of carbon capture and storage annually by 2040.

- (2)

- Diversified energy business development. Some European IOCs have reduced oil and gas production and accelerated the layout of clean energy production systems. For example, Shell has sold oil and gas assets, such as closing the Tabangao refinery and selling assets in the Permian Basin. On the other hand, it has invested in multiple non-traditional oil and gas businesses, including investing in and participating in projects such as wind, solar, bioenergy, and electric vehicle charging infrastructure. The diversification of business also means a decrease in oil and gas production by oil companies, significantly reducing the carbon emissions of all energy consuming units at the root, thereby promoting energy conservation, carbon emissions reduction, and green development globally.

- (3)

- Providing support for low-carbon businesses through asset restructuring. The results indicate that the level of corporate development and profitability of the oil companies themselves is an important driving factor for comprehensively reducing corporate carbon emissions and improving production efficiency. The improvement in financial conditions has boosted investors’ confidence in oil companies, allowing them to continuously optimize their investment portfolios without being affected by external capital market pressures. The adjustment in an asset portfolio can effectively reduce emissions in range 1 + range 2. Whether it is debt repayment or asset restructuring, the result is an indirect or direct increase in the proportion of low-carbon assets, ultimately having a positive impact on reducing CO2 emissions. For example, bp is trying to fundamentally change its capital allocation, only retaining high-value oil and gas assets, and it will focus on investment in renewable energy and other low-carbon energy. Through the sale of upstream high-carbon assets located in Norway, the UK, and Romania and other countries, ExxonMobil is paying more attention to projects in the Permian Basin that have lower breakeven points, greater economic scales, and more flexible expenditures, and regards the Permian Basin as a new production center.

- (4)

- Transformation through improvements in the level of digitization and intelligence. Under the new round of the oil and gas scientific and technological revolution and the digital revolution, digitization and intelligence technologies have opened up a new way for the sustainable development of the oil and gas industry, and provided a new kinetic energy for green and low-carbon development. Oil companies have integrated new digitalization technologies such as the Internet of Things, big data analysis, artificial intelligence, blockchain, digital twins and other digitalization technologies with the oil and gas industry, reducing the carbon emissions of the oil and gas industry chain. For example, Equinor‘s Johan Sverdrup large-scale intelligent oil field, which has adopted digital technologies on a large scale at the beginning of its construction, saved construction costs and reduced the overall level of carbon emissions from the field.

5. Conclusions

As an important energy supplier and economic entity, large multinational oil companies play an essential role in global energy layout and economic development, and the low-carbon transition strategies and efficiency of these oil companies will also have far-reaching impacts on global energy transition.

Although most energy companies have announced relevant measures to achieve low-carbon and green development in recent years, few studies have been conducted to discuss the efficiency and specific driving factors of energy companies’ low-carbon transitions. Therefore, this study selected 10 large multinational oil companies and examined their carbon emission reduction strategies or targets from the perspective of input–output efficiency by using the super-SBM model. The underlying driving factors can be found through use of LMDI models. The results show that although the carbon emissions of the oil companies have been reduced year by year, the carbon emission efficiency is still not high, and there is much room for improvement. Specifically, on analyzing the factors affecting carbon emissions, it can be found that the energy efficiency and the profitability of the companies have the greatest contribution to the carbon emission efficiency. The enhancement in energy efficiency can directly reduce the carbon emissions of the companies in the short term, while the operation level and profitability of the companies can reduce the carbon emissions of the companies in the long-term development. Aiming at these main driving factors, this paper puts forward targeted policy recommendations for the low-carbon transition of multinational oil companies.

However, this paper still suffers from the following limits. Firstly, because of the limitation of data availability, this paper fails to evaluate the carbon emission efficiency of more international oil companies, since some oil companies will not always disclose their energy consumption data. Secondly, the time for the implementation of low-con transition strategies is still relatively short, and there exists a time lag in which the corporate management strategies come into play, therefore this paper has failed to evaluate the effectiveness of carbon emission strategies of different corporations over a longer time cycle. Thirdly, besides the input–output variables and driving factors considered in super-SBM and LMDI models, the factors influencing the energy transition strategies of large-scale oil companies may be more diverse and complex. For example, the preferences of decision-makers, or the market uncertainty, can also impact the strategies. This paper only focusses on the factors related to corporate production and energy consumption, neglecting other subjective factors and the market environment. However, in the future, this study will continue to include a wider range of energy companies, evaluate the long-term effectiveness of different low-carbon transition strategies, and try to incorporate more influence factors of oil companies’ low-carbon transition.

Author Contributions

X.T.: conceptualization, methodology, validation, writing—original draft, visualization. Q.Z.: conceptualization, validation, supervision, funding acquisition. C.L., H.Z. and H.X.: revision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Major Program of National Social Science Foundation of China, Research on the Path and Strategy for Promoting the Energy Revolution towards Carbon Neutrality, (No. 21ZDA030), XinJiang Natura Science Foundation, (No. 2022D01E56), and the Open Research Fund of Tianshan Research Institute (No. TSKF20220010).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Haiyun Xu was employed by the company Petrochina Natural Gas Marketing Company. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Contribution of changes in energy consumption structure to carbon emissions under the additive equation.

Table A1.

Contribution of changes in energy consumption structure to carbon emissions under the additive equation.

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Equinor | 2.52 | 0.47 | 0.94 | 0.04 |

| 2 | Petrobras | −0.71 | 0.65 | −0.13 | −0.10 |

| 3 | ENI | 1.82 | 1.00 | 2.31 | 4.97 |

| 4 | Exxon Mobil | 3.16 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 5 | bp | 1.00 | 1.00 | −0.36 | 0.48 |

| 6 | Shell | 40.39 | −0.01 | −0.40 | 0.33 |

| 7 | Chevron | 1.22 | 0.55 | 1.60 | 0.20 |

| 8 | TotalEnergies | 1.00 | 0.41 | 1.05 | 0.23 |

| 9 | CNPC | 1.46 | 1.69 | −4.90 | 0.96 |

| 10 | Sinopec | −1.01 | 7.49 | 30.42 | 0.93 |

Table A2.

Contribution of changes in energy consumption intensity to carbon emissions under the additive equation.

Table A2.

Contribution of changes in energy consumption intensity to carbon emissions under the additive equation.

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Equinor | −17.25 | −2.87 | 6.73 | 10.82 |

| 2 | Petrobras | −4.71 | −5.91 | −2.92 | 2.66 |

| 3 | ENI | −2.75 | −4.18 | −9.12 | 23.73 |

| 4 | Exxon Mobil | −3.81 | −5.62 | 0.51 | 87.74 |

| 5 | bp | 19.16 | −5.41 | 2.99 | 4.67 |

| 6 | Shell | −47.38 | −6.22 | 8.55 | 2.70 |

| 7 | Chevron | −0.82 | −2.71 | −10.58 | 6.52 |

| 8 | TotalEnergies | −95.72 | −1.88 | 2.83 | −0.88 |

| 9 | CNPC | −1.66 | 18.48 | 13.73 | 1.27 |

| 10 | Sinopec | 3.93 | 181.83 | −59.80 | 1.66 |

Table A3.

Contribution of changes in economic development level of companies to carbon emissions under the additive equation.

Table A3.

Contribution of changes in economic development level of companies to carbon emissions under the additive equation.

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Equinor | 18.85 | 3.33 | −6.73 | −9.13 |

| 2 | Petrobras | 3.85 | 3.31 | 4.73 | −1.59 |

| 3 | ENI | 2.14 | 3.98 | 7.19 | −28.60 |

| 4 | Exxon Mobil | 3.32 | 5.04 | −3.51 | −89.49 |

| 5 | bp | −14.71 | 5.06 | −1.88 | −3.83 |

| 6 | Shell | 13.81 | 7.23 | −8.22 | −1.30 |

| 7 | Chevron | 0.54 | 3.09 | 12.09 | −5.32 |

| 8 | TotalEnergies | 130.46 | 2.75 | −3.19 | 1.66 |

| 9 | CNPC | 1.20 | −12.07 | −8.58 | −1.64 |

| 10 | Sinopec | −12.57 | −156.78 | 29.94 | −2.04 |

Table A4.

Contribution of changes in the company size to carbon emissions under the additive equation.

Table A4.

Contribution of changes in the company size to carbon emissions under the additive equation.

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Equinor | −3.13 | 0.08 | 0.05 | −0.73 |

| 2 | Petrobras | 2.57 | 2.95 | −0.67 | 0.03 |

| 3 | ENI | −0.21 | 0.20 | 0.62 | 0.89 |

| 4 | Exxon Mobil | −1.67 | 0.59 | 3.00 | 1.75 |

| 5 | bp | −4.46 | 0.35 | 0.25 | −0.32 |

| 6 | Shell | −5.82 | 0.00 | 1.07 | −0.74 |

| 7 | Chevron | 0.06 | 0.07 | −2.11 | −0.40 |

| 8 | TotalEnergies | −34.74 | −0.28 | 0.31 | 0.00 |

| 9 | CNPC | 0.00 | −7.09 | 0.74 | 0.41 |

| 10 | Sinopec | 10.66 | −31.53 | 0.45 | 0.44 |

References

- Masnadi, M.S.; Brandt, A.R. Climate impacts of oil extraction increase significantly with oilfield age. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2017, 7, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.Y. Crude oil trade and green shipping choices. Transp. Res. Part D-Transp. Environ. 2018, 65, 618–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenner, D.; Heede, R. White knights, or horsemen of the apocalypse? Prospects for Big Oil to align emissions with a 1.5 °C pathway. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 79, 102049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Orellana, A.; Sleep, S.; Laurenzi, I.J.; MacLean, H.L.; Bergerson, J.A. Statistically enhanced model of oil sands operations: Well-to-wheel comparison of in situ oil sands pathways. Energy 2020, 208, 118250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, Y.Y.; Gunasekaran, A.; Musa, A.; El-Berishy, N.M.; Abubakar, T.; Ambursa, H.M. The UK oil and gas supply chains: An empirical analysis of adoption of sustainable measures and performance outcomes. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 146, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Yu, Q.; Shi, X. Investment Analysis and Strategic Forecast of Low-carbon Business for International Oil Companies. Pet. New Energy 2022, 34, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Fattouh, B.; Poudineh, R.; West, R. The rise of renewables and energy transition: What adaptation strategy exists for oil companies and oil-exporting countries? Energy Transit. 2019, 3, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Guo, L.; Zhang, Y. Oil and gas companies’ low-carbon emission transition to integrated energy companies. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 686, 1202–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, P.; Srivastava, R.K.; De, S. Integrating Greenhouse gases (GHG) assessment for low carbon economy path: Live case study of Indian national oil company. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liang, Y.; Ni, W.; Liao, Q.; Xu, N.; Li, L.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, H. Pipesharing: Economic-environmental benefits from transporting biofuels through multiproduct pipelines. Appl. Energy 2022, 311, 118684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, X.-B.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, X. Pass-through of diesel taxes and the effect on carbon emissions: Evidence from China. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 321, 115857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liang, X.; Cockerill, T. Getting ready for carbon capture and storage through a ‘CCS (Carbon Capture and Storage) Ready Hub’: A case study of Shenzhen city in Guangdong province, China. Energy 2011, 36, 5916–5924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, J.K.; Reay, D.S.; Haszeldine, R.S. Gas-fired power in the UK: Bridging supply gaps and implications of domestic shale gas exploitation for UK climate change targets. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 616–617, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, R.J.; Haszeldine, R.S. Can Producing Oil Store Carbon? Greenhouse Gas Footprint of CO2EOR, Offshore North Sea. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 5788–5795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltanieh, M.; Zohrabian, A.; Gholipour, M.J.; Kalnay, E. A review of global gas flaring and venting and impact on the environment: Case study of Iran. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2016, 49, 488–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintino, A.; Catalão-Lopes, M.; Lourenço, J.C. Can switching from gasoline to aromatics mitigate the price risk of refineries? Energy Policy 2019, 134, 110963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, S.C.; Oh, T.H. Review on Malaysia’s national energy developments: Key policies, agencies, programmes and international involvements. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 2916–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshmehzangi, A.; Xie, L.; Tan-Mullins, M. The role of international actors in low-carbon transitions of Shenzhen’s International Low Carbon City in China. Cities 2018, 74, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Yang, J.; Yan, J.; Lee, C.; Hashim, H.; Chen, B. A holistic low carbon city indicator framework for sustainable development. Appl. Energy 2017, 185, 1919–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Xu, X.; Li, Z.; Du, P.; Ye, J. Can low-carbon technological innovation truly improve enterprise performance? The case of Chinese manufacturing companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 125949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Yao, S.; Zhai, M. Enterprise Low-Carbon Behavior, Financial Performance and Economic Transformation——Data from Listed Companies in China. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 275, 02004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasmukhanova, A.E.; Evtushenko, E.V.; Burenina, I.V.; Biryukova, V.V.; Tasmukhanova, G.E. Transformation Oil and Gas Company: Changes and Benefits. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Modern Education and Economic Management (ICMEEM 2019), Fuzhou, China, 25–26 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sarrakh, R.; Renukappa, S.; Suresh, S. Evaluation of challenges for sustainable transformation of Qatar oil and gas industry: A graph theoretic and matrix approach. Energy Policy 2022, 162, 112766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ke, Y.; Wang, J. Evaluation of the sustainable competitiveness of China’s state-owned oil enterprises under the low-carbon energy transformation. China Min. Mag. 2021, 30, 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, W.C.; Li, X. Can Industrial Agglomeration Facilitate Green Development? Evidence From China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 745465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.N.; Luo, S.M.; Xu, G.H.; Zhou, G.Y. Quantitative Analysis and Evaluation of Enterprise Group Financial Company Efficiency in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).