Financial and Economic Stability of Energy Sector Enterprises as a Condition for Poland’s Energy Security—Legal and Economic Aspects

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Macroeconomic conditions, i.e., economic situation, inflation, demand, supply, legal regulations, economic growth dynamics, sociocultural factors, technical and technological development, tax system, financial system, currency stability, etc.;

- Microeconomic conditions, i.e., production profile, fixed assets, amount of capital, product quality, sales profitability, cooperation links, implementation of scientific and technical progress, skills of employees and management, level of technology, trademark, entrepreneurship of the staff, resource management, etc.

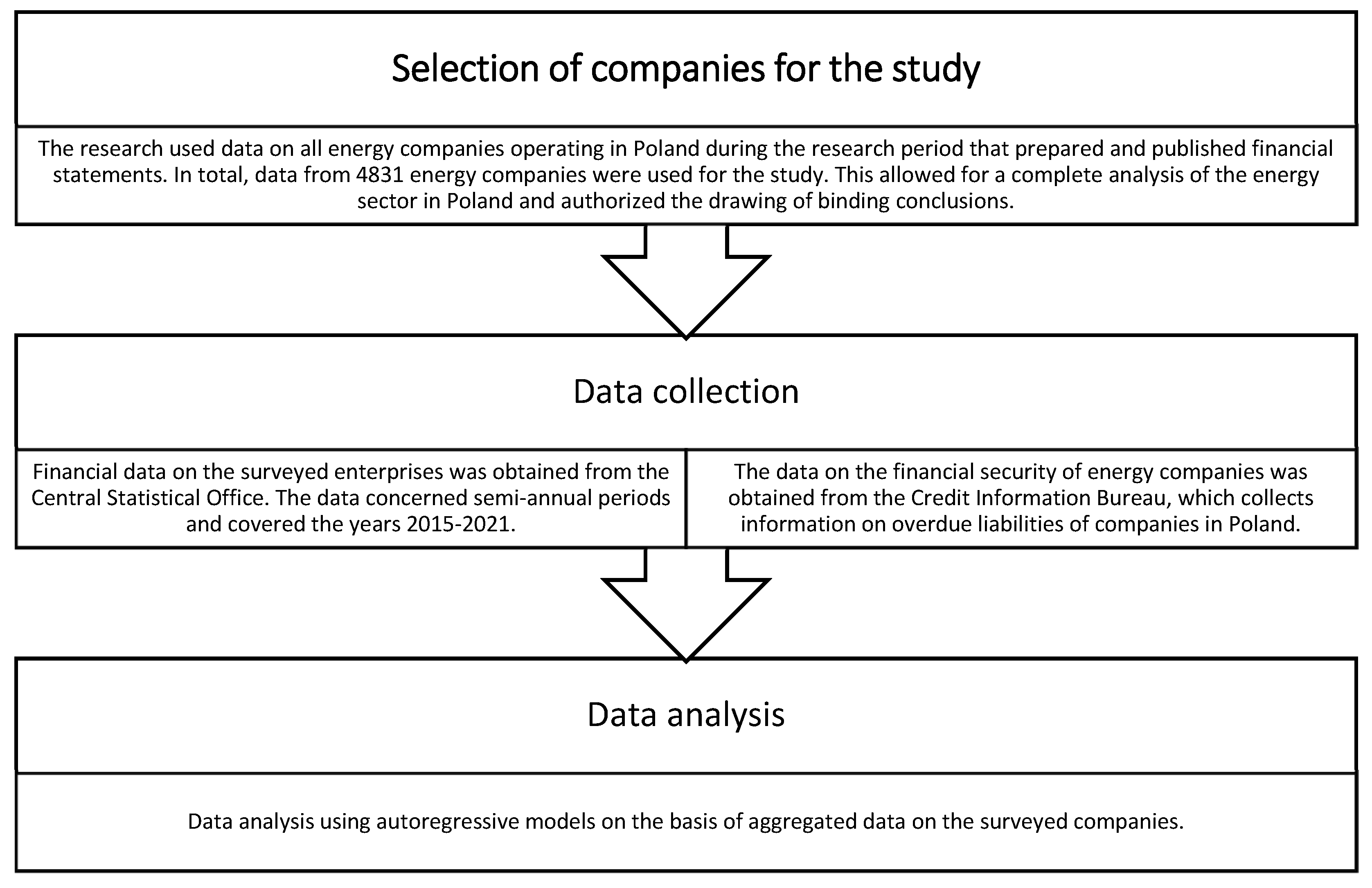

2. Materials and Methods

- Resultant: Earnings Before Deducting Interest and Taxes (EBIT) margin, Return on Equity (ROE), return on invested capital (ROIC) and Return on Assets (ROA);

- Cost: depreciation to net sales revenues, materials to net sales revenues, energy to net sales revenues, third-party services to net sales revenues, costs of salaries and overheads to net sales revenues, value of goods and materials sold to revenues net sales, and other costs to net sales revenues;

- Balance-sheet structure: fixed assets, current assets, equity, long-term liabilities, short-term liabilities, interest-bearing debt (excluding other financial liabilities;

- Debt: EBITDA × A/(long-term liabilities + short-term liabilities), interest coverage ratio, debt under loans, borrowings and securities issues/equity, (long-term liabilities + short-term liabilities)/total assets equity/total assets and equity/fixed assets coverage of fixed assets with fixed capital;

- Liquidity: current liquidity ratio, increased liquidity ratio and cash liquidity ratio;

- Operational efficiency: rotation of trade receivables in days, rotation of inventories in days, rotation of trade payables in days and cash conversion cycle.

- Economic situation: gross domestic product (GDP), Retail Sales and Consumer Price Index (CPI);

- Situation on the market of energy resources (WTI Oil, Gas (Netherlands) and Coal (Newcastle)).

- Share of unprofitable companies in the energy sector;

- Share of companies with delays in repayment of credits and loans exceeding 90 days.

- Analysis of normative acts, official statistical data, industry reports and analyses, as well as and data obtained through a public information request.

- Analysis of statistical data on the Polish energy sector.

- Selection of variables determining the level of financial security of energy companies and variables that can affect it, divided into internal variables and external variables.

- Conducting statistical analysis using autoregressive models:

- ▪

- Selection of the lag order of the variables,

- ▪

- Estimation of VAR model parameters using the classical method of least squares.

3. Results

3.1. Limits of State Intervention in Market Processes

3.2. Energy Security as a Prerequisite for Public Financing

3.3. Factors Determining the Financial Security of Energy Companies

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Selected Financial Data Characterizing the Surveyed Energy Companies in Poland

| General Information | Calculation Formula | Unit | 1H 2015 | 2H 2015 | 1H 2016 | 2H 2016 | 1H 2017 | 2H 2017 | 1H 2018 | 2H 2018 | 1H 2019 | 2H 2019 | 1H 2020 | 2H 2020 | 1H 2021 | 2H 2021 |

| Number of companies reporting | Number of companies that have submitted a report | pcs. | 48,732 | 52,395 | 49,091 | 52,711 | 48,729 | 52,060 | 46,679 | 50,481 | 46,240 | 50,783 | 45,299 | 49,600 | 43,784 | 48,341 |

| Working in the sector | Number of employees in the sector | persons | 5,061,172 | 5,202,676 | 5,203,431 | 5,371,370 | 5,339,519 | 5,503,175 | 5,398,166 | 5,556,931 | 5,399,996 | 5,588,736 | 5,318,741 | 5,493,016 | 5,363,801 | 5,555,250 |

| Company results | Calculation formula | unit | 1H 2015 | 2H 2015 | 1H 2016 | 2H 2016 | 1H 2017 | 2H 2017 | 1H 2018 | 2H 2018 | 1H 2019 | 2H 2019 | 1H 2020 | 2H 2020 | 1H 2021 | 2H 2021 |

| Total revenue | Net sales revenue + other operating revenue + financial revenue | mln PLN | 1,483,574 | 1,632,588 | 1,525,487 | 1,727,872 | 1,670,087 | 1,804,185 | 1,752,488 | 1,938,397 | 1,864,500 | 2,019,815 | 1,763,740 | 2,063,515 | 2,090,928 | 2,601,563 |

| Year-on-year change in total revenue [%] | Total revenue/year-to-date total revenue | % | bd | bd | 2.80% | 5.80% | 9.50% | 4.40% | 4.90% | 7.40% | 6.40% | 4.20% | −5.40% | 2.20% | 18.60% | 26.10% |

| Net sales revenue | Net sales revenue | mln PLN | 1,436,069 | 1,579,402 | 1,471,172 | 1,673,536 | 1,611,066 | 1,745,157 | 1,696,669 | 1,889,097 | 1,810,163 | 1,968,167 | 1,706,339 | 1,994,714 | 2,018,822 | 2,512,652 |

| Year-on-year change in net revenue [%] | Net sales revenue/year to date net sales revenue | % | bd | bd | 2.40% | 6.00% | 9.50% | 4.30% | 5.30% | 8.20% | 6.70% | 4.20% | −5.70% | 1.30% | 18.30% | 26.00% |

| Net revenue in the country | Net revenue—net revenue from sales treated as exports | mln PLN | 1,126,597 | 1,258,768 | 1,142,878 | 1,318,171 | 1,241,492 | 1,359,521 | 1,311,855 | 1,487,576 | 1,389,456 | 1,531,890 | 1,330,176 | 1,537,107 | 1,535,690 | 1,954,500 |

| Net export revenues | Net sales revenues treated as exports | mln PLN | 309,473 | 320,634 | 328,294 | 355,365 | 369,574 | 385,636 | 384,813 | 401,522 | 420,707 | 436,277 | 376,164 | 457,607 | 483,132 | 558,152 |

| Sales profit | Sales profit | mln PLN | 71,279 | 71,029 | 72,687 | 84,476 | 76,108 | 88,494 | 84,158 | 87,670 | 83,730 | 96,364 | 78,142 | 106,170 | 116,231 | 147,127 |

| Sales profit margin | Profit (loss) on sales/revenue from sales | % | 5.00% | 4.50% | 4.90% | 5.00% | 4.70% | 5.10% | 5.00% | 4.60% | 4.60% | 4.90% | 4.60% | 5.30% | 5.80% | 5.90% |

| EBIT | Operating profit | mln PLN | 77,745 | 75,121 | 80,958 | 88,658 | 83,608 | 91,896 | 91,532 | 87,621 | 90,641 | 98,285 | 87,305 | 111,135 | 137,628 | 170,069 |

| EBIT margin | EBIT/net sales revenue | % | 5.40% | 4.80% | 5.50% | 5.30% | 5.20% | 5.30% | 5.40% | 4.60% | 5.00% | 5.00% | 5.10% | 5.60% | 6.80% | 6.80% |

| EBITDA | EBIT + amortization | mln PLN | 124,862 | 134,530 | 130,405 | 141,374 | 135,391 | 147,947 | 145,302 | 146,506 | 149,905 | 163,786 | 151,102 | 178,666 | 203,818 | 243,316 |

| EBITDA margin | EBITDA/net sales revenue | % | 8.70% | 8.50% | 8.90% | 8.40% | 8.40% | 8.50% | 8.60% | 7.80% | 8.30% | 8.30% | 8.90% | 9.00% | 10.10% | 9.70% |

| Net profit | Net profit | mln PLN | 68,807 | 51,818 | 73,453 | 66,143 | 79,085 | 75,700 | 75,699 | 68,327 | 79,115 | 75,067 | 65,193 | 83,671 | 123,261 | 145,491 |

| Net profit margin | Net profit/net sales revenue | % | 4.80% | 3.30% | 5.00% | 4.00% | 4.90% | 4.30% | 4.50% | 3.60% | 4.40% | 3.80% | 3.80% | 4.20% | 6.10% | 5.80% |

| ROE | Net profit/equity capital | % | 10.30% | 7.40% | 10.60% | 9.20% | 11.00% | 9.90% | 10.00% | 8.60% | 10.00% | 9.10% | 8.00% | 9.80% | 14.10% | 15.40% |

| ROIC | EBIT/fixed capital | % | 8.40% | 7.80% | 8.40% | 8.80% | 8.30% | 8.70% | 8.70% | 8.00% | 8.20% | 8.30% | 7.30% | 8.90% | 10.90% | 12.70% |

| ROA | Net profit/total assets | % | 5.20% | 3.70% | 5.20% | 4.50% | 5.40% | 4.90% | 4.80% | 4.20% | 4.80% | 4.30% | 3.70% | 4.60% | 6.50% | 7.00% |

| Costs | Wzór | unit | 1H 2015 | 2H 2015 | 1H 2016 | 2H 2016 | 1H 2017 | 2H 2017 | 1H 2018 | 2H 2018 | 1H 2019 | 2H 2019 | 1H 2020 | 2H 2020 | 1H 2021 | 2H 2021 |

| Depreciation to net sales revenue | Depreciation/net sales revenue | % | 3.30% | 3.80% | 3.40% | 3.10% | 3.20% | 3.20% | 3.20% | 3.10% | 3.30% | 3.30% | 3.70% | 3.40% | 3.30% | 2.90% |

| Materials to net sales revenue | Materials/net sales revenue | % | 25.20% | 24.00% | 24.60% | 23.20% | 24.80% | 24.50% | 25.30% | 24.20% | 24.80% | 23.50% | 22.70% | 23.10% | 24.40% | 24.70% |

| Energy to net sales revenue | Energy/net sales revenue | % | 1.60% | 1.50% | 1.50% | 1.40% | 1.40% | 1.30% | 1.40% | 1.20% | 1.50% | 1.30% | 1.60% | 1.40% | 1.60% | 1.40% |

| Third-party services to net sales revenue | Third-party services/net sales revenue | % | 14.10% | 15.60% | 14.40% | 15.30% | 14.10% | 15.60% | 14.20% | 15.60% | 14.10% | 15.90% | 14.90% | 15.40% | 14.10% | 14.80% |

| Costs of salaries and surcharges to net sales revenue | Costs of salaries and surcharges/net sales revenue | % | 11.10% | 11.00% | 11.60% | 11.20% | 11.50% | 11.50% | 11.80% | 11.70% | 12.00% | 12.00% | 12.90% | 12.50% | 12.00% | 11.40% |

| Value of goods and materials sold to net sales revenue | Value of goods and materials sold/net sales revenue | % | 34.80% | 34.90% | 34.60% | 35.40% | 35.40% | 34.70% | 34.40% | 34.70% | 34.80% | 34.50% | 34.40% | 34.40% | 33.90% | 34.20% |

| Other costs to net sales revenue | Other costs/net sales revenue | % | 4.90% | 4.80% | 5.10% | 5.20% | 4.80% | 4.20% | 4.80% | 4.90% | 4.90% | 4.60% | 5.10% | 4.60% | 5.00% | 4.70% |

| Balance sheet | Calculation formula | unit | 1H 2015 | 2H 2015 | 1H 2016 | 2H 2016 | 1H 2017 | 2H 2017 | 1H 2018 | 2H 2018 | 1H 2019 | 2H 2019 | 1H 2020 | 2H 2020 | 1H 2021 | 2H 2021 |

| Fixed assets | Fixed assets | mln PLN | 1,633,052 | 1,719,012 | 1,718,768 | 1,784,884 | 1,780,950 | 1,860,337 | 1,867,604 | 1,946,222 | 1,977,703 | 2,095,005 | 2,114,501 | 2,197,861 | 2,175,141 | 2,283,354 |

| Current assets | Current assets | mln PLN | 1,038,992 | 1,070,753 | 1,096,120 | 1,151,915 | 1,159,568 | 1,242,810 | 1,263,768 | 1,318,976 | 1,336,489 | 1,401,498 | 1,387,729 | 1,474,313 | 1,611,894 | 1,864,970 |

| Equity capital | Equity capital | mln PLN | 1,340,901 | 1,396,780 | 1,384,339 | 1,436,900 | 1,437,729 | 1,530,329 | 1,518,697 | 1,584,554 | 1,583,320 | 1,656,711 | 1,639,715 | 1,710,816 | 1,746,092 | 1,891,006 |

| Long-term liabilities | Long-term liabilities | mln PLN | 413,681 | 437,434 | 449,075 | 473,884 | 467,295 | 479,567 | 492,900 | 497,317 | 523,482 | 562,324 | 628,099 | 644,477 | 645,746 | 675,111 |

| Short-term liabilities | Short-term liabilities | mln PLN | 692,060 | 715,870 | 735,707 | 776,289 | 785,899 | 833,932 | 861,741 | 908,902 | 927,207 | 971,887 | 925,303 | 982,058 | 1,055,237 | 1,217,107 |

| Interest-bearing debt (excluding items of other financial liabilities) | Interest-bearing debt (excluding items of other financial liabilities) | mln PLN | 547,817 | 582,553 | 591,274 | 620,217 | 622,368 | 623,688 | 645,364 | 669,741 | 687,418 | 725,909 | 784,463 | 791,804 | 794,714 | 858,227 |

| Debt ratios | Calculation formula | unit | 1H 2015 | 2H 2015 | 1H 2016 | 2H 2016 | 1H 2017 | 2H 2017 | 1H 2018 | 2H 2018 | 1H 2019 | 2H 2019 | 1H 2020 | 2H 2020 | 1H 2021 | 2H 2021 |

| EBITDA/(long-term liabilities + short-term liabilities) | EBITDA/(long-term liabilities + short-term liabilities) | − | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.26 |

| Interest service coverage ratio | (Net income + depreciation and amortization + income tax + interest)/interests | − | 11.8 | 9.9 | 12.7 | 11 | 13 | 12.2 | 12.4 | 12.6 | 13.4 | 11.4 | 12.5 | 14.8 | 22.6 | 20.6 |

| Financing structure indicators | Calculation formula | unit | 1H 2015 | 2H 2015 | 1H 2016 | 2H 2016 | 1H 2017 | 2H 2017 | 1H 2018 | 2H 2018 | 1H 2019 | 2H 2019 | 1H 2020 | 2H 2020 | 1H 2021 | 2H 2021 |

| Debt from loans, borrowings and securities issues/shareholders’ equity | Debt from loans, borrowings and securities issues/shareholders’ equity | % | 40.90% | 41.70% | 42.70% | 43.20% | 43.30% | 40.80% | 42.50% | 42.30% | 43.40% | 43.80% | 47.80% | 46.30% | 45.50% | 45.40% |

| (long-term liabilities + short-term liabilities)/total assets | (Long-term liabilities + short-term liabilities)/total assets | % | 41.40% | 41.30% | 42.10% | 42.60% | 42.60% | 42.30% | 43.30% | 43.10% | 43.80% | 43.90% | 44.40% | 44.30% | 44.90% | 45.60% |

| Equity capital/total assets | Equity capital/total assets | % | 50.20% | 50.10% | 49.20% | 48.90% | 48.90% | 49.30% | 48.50% | 48.50% | 47.80% | 47.40% | 46.80% | 46.60% | 46.10% | 45.60% |

| Equity capital/fixed assets | Equity capital/fixed assets | % | 82.10% | 81.30% | 80.50% | 80.50% | 80.70% | 82.30% | 81.30% | 81.40% | 80.10% | 79.10% | 77.50% | 77.80% | 80.30% | 82.80% |

| Coverage of fixed assets with fixed capital | (Equity capital + non-current liabilities)/fixed assets | % | 107.40% | 106.70% | 106.70% | 107.10% | 107.00% | 108.00% | 107.70% | 107.00% | 106.50% | 105.90% | 107.30% | 107.20% | 110.00% | 112.40% |

| Liquidity ratios | Calculation formula | unit | 1H 2015 | 2H 2015 | 1H 2016 | 2H 2016 | 1H 2017 | 2H 2017 | 1H 2018 | 2H 2018 | 1H 2019 | 2H 2019 | 1H 2020 | 2H 2020 | 1H 2021 | 2H 2021 |

| Current ratio | Current assets/current liabilities | − | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.49 | 1.48 | 1.48 | 1.49 | 1.47 | 1.45 | 1.44 | 1.44 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.53 | 1.53 |

| Increased liquidity ratio | (Current assets/inventories)/current liabilities | − | 1.11 | 1.1 | 1.11 | 1.1 | 1.09 | 1.1 | 1.08 | 1.06 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.11 | 1.11 | 1.14 | 1.13 |

| Cash flow ratio | Cash and cash equivalents/current liabilities | − | 0.28 | 0.3 | 0.28 | 0.3 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.29 |

| Working capital turnover ratios | Calculation formula | unit | 1H 2015 | 2H 2015 | 1H 2016 | 2H 2016 | 1H 2017 | 2H 2017 | 1H 2018 | 2H 2018 | 1H 2019 | 2H 2019 | 1H 2020 | 2H 2020 | 1H 2021 | 2H 2021 |

| Trade receivables turnover in days | Trade receivables/net sales revenue | days | 47.5 | 43.1 | 48.8 | 44.5 | 46.6 | 45.5 | 47.6 | 44.1 | 47.4 | 43.9 | 47 | 42.4 | 45.7 | 41.2 |

| Inventory turnover in days | Inventory/net sales revenue | days | 34.1 | 32.1 | 34.2 | 32.1 | 34.1 | 33.5 | 35.6 | 34.2 | 35.7 | 34.5 | 38.4 | 34.7 | 36.6 | 35.3 |

| Trade payables turnover in days | Trade payables/net sales revenue | days | 43.7 | 41.1 | 44.7 | 42.9 | 43.8 | 44.9 | 45.7 | 42.9 | 44.2 | 43.1 | 43.8 | 42.5 | 44.2 | 42.5 |

| Cash conversion cycle | Inventory turnover in days + receivables turnover in days—payables turnover in days | days | 38 | 34.2 | 38.3 | 33.8 | 36.8 | 34.1 | 37.5 | 35.3 | 38.9 | 35.3 | 41.6 | 34.7 | 38.2 | 34 |

| Investment cycle | Calculation formula | unit | 1H 2015 | 2H 2015 | 1H 2016 | 2H 2016 | 1H 2017 | 2H 2017 | 1H 2018 | 2H 2018 | 1H 2019 | 2H 2019 | 1H 2020 | 2H 2020 | 1H 2021 | 2H 2021 |

| Capital expenditures | Capital expenditures | mln PLN | 62770 | 101449 | 59914 | 85706 | 58733 | 93588 | 64712 | 104297 | 76817 | 112435 | 71689 | 104171 | 79254 | 120710 |

| Investment expenditures on average per company | Capital expenditures/number of companies that reported | mln PLN | 1.29 | 1.94 | 1.22 | 1.63 | 1.21 | 1.8 | 1.39 | 2.07 | 1.66 | 2.21 | 1.58 | 2.1 | 1.81 | 2.5 |

| Labor productivity | (Net income from sales of products + net income from sales of goods and materials)/employment | mln PLN | 0.28 | 0.302 | 0.28 | 0.309 | 0.299 | 0.315 | 0.31 | 0.337 | 0.331 | 0.349 | 0.318 | 0.361 | 0.372 | 0.447 |

| Import and export | Calculation formula | unit | 1H 2015 | 2H 2015 | 1H 2016 | 2H 2016 | 1H 2017 | 2H 2017 | 1H 2018 | 2H 2018 | 1H 2019 | 2H 2019 | 1H 2020 | 2H 2020 | 1H 2021 | 2H 2021 |

| Share of exports in total revenue | Export sales/total revenues | % | 20.90% | 19.60% | 21.50% | 20.60% | 22.10% | 21.40% | 22.00% | 20.70% | 22.60% | 21.60% | 21.30% | 22.20% | 23.10% | 21.50% |

| Share of imports in operating expenses | Value of import purchases/total revenues | % | 21.60% | 20.80% | 22.00% | 21.00% | 22.40% | 22.50% | 22.30% | 22.30% | 22.70% | 21.10% | 19.90% | 20.60% | 22.50% | 23.00% |

| Economic situation | Calculation formula | unit | 1H 2015 | 2H 2015 | 1H 2016 | 2H 2016 | 1H 2017 | 2H 2017 | 1H 2018 | 2H 2018 | 1H 2019 | 2H 2019 | 1H 2020 | 2H 2020 | 1H 2021 | 2H 2021 |

| PKB | GDP | % | 0.70% | 1.20% | 1.30% | 2.20% | 0.90% | 1.70% | 1.30% | 0.90% | 0.80% | 0.50% | −9.10% | 0.10% | 2.20% | 1.60% |

| Sprzedaż detaliczna | Retail sales | % | 4.70% | 5.70% | 4.30% | 7.40% | 7.40% | 8.80% | 6.10% | 6.90% | 5.60% | 5.20% | −7.70% | −5.30% | 13.90% | 12.10% |

| CPI | CPI | % | −0.80% | −0.50% | −0.80% | 0.80% | 1.50% | 2.10% | 2.00% | 1.10% | 2.60% | 3.40% | 3.30% | 2.40% | 4.40% | 8.60% |

| Price of raw materials | Calculation formula | unit | 1H 2015 | 2H 2015 | 1H 2016 | 2H 2016 | 1H 2017 | 2H 2017 | 1H 2018 | 2H 2018 | 1H 2019 | 2H 2019 | 1H 2020 | 2H 2020 | 1H 2021 | 2H 2021 |

| WTI crude oil | Market quotations | USD | 59.79 | 37.14 | 48.41 | 52.67 | 42.98 | 58.1 | 66.7 | 45.39 | 55.93 | 61.55 | 39.06 | 47.75 | 73.28 | 73.31 |

| Gas (Netherlands) | Market quotations | USD | 20.515 | 14.667 | 14.805 | 17.833 | 14.751 | 19.956 | 21.594 | 22.608 | 10.41 | 12.558 | 5.565 | 17.92 | 31.767 | 134.526 |

| Coal (Newcastle) | Market quotations | USD | 60.24 | 51.91 | 53.12 | 86.81 | 80.65 | 100.24 | 114.47 | 101.63 | 70.76 | 66.81 | 53.06 | 81.26 | 127.7 | 169.38 |

| Measures of financial security | Calculation formula | unit | 1H 2015 | 2H 2015 | 1H 2016 | 2H 2016 | 1H 2017 | 2H 2017 | 1H 2018 | 2H 2018 | 1H 2019 | 2H 2019 | 1H 2020 | 2H 2020 | 1H 2021 | 2H 2021 |

| Share of unprofitable companies in the energy sector | Number of unprofitable companies/number of companies that have reported | % | 28.70% | 28.70% | 29.00% | 29.00% | 30.10% | 30.10% | 28.30% | 28.30% | 28.20% | 28.20% | 29.00% | 29.00% | 26.50% | 26.50% |

| Share of companies with delays in repayment of credits and loans exceeding 90 days | Number of companies with delays of more than 90 in repayment of loans and credits/number of companies that have loans and credits | % | 5.00% | 5.60% | 7.70% | 8.30% | 10.90% | 13.00% | 12.70% | 13.30% | 11.60% | 11.90% | 13.30% | 12.10% | 11.30% | 11.50% |

References

- Mara, D.; Nate, S.; Stavytskyy, A.; Kharlamova, G. The Place of Energy Security in the National Security Framework: An Assessment Approach. Energies 2022, 15, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igliński, B.; Iglińska, A.; Koziński, G.; Skrzatek, M.; Buczkowski, R. Wind energy in Poland—History, current state, surveys, Renewable Energy Sources Act, SWOT analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 64, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, D.K. State expenditure from a Marxist perspective. J. Public Econ. 1978, 9, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šliogerienė, J.; Kaklauskas, A.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Bivainis, J.; Seniut, M. Environment factors of energy companies and their effect on value: Analysis model and applied method. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2009, 15, 490–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasser, P. A review on energy security indices to compare country performances. Energy Policy 2020, 139, 111339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayerweather, J. International Business Management: A Conceptual Framework; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1968; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Dźwigoł, H.; Dźwigoł, M.; Zhyvko, Z.; Miśkiewicz, R.; Pushak, H. Evaluation of the energy security as a component of national security of the country. J. Secur. Sustain. 2019, 8, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusu, V.D.; Roman, A. An empirical analysis of factors affecting competitiveness of C.E.E. countries. Econ. Res. Istraživanja 2018, 31, 2044–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, A.A. Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management: Can We Afford to Neglect Them in the Twenty-first Century Business School? Br. J. Manag. 1996, 7, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lütkepohl, H. Vector autoregressive models. In Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Empirical Macroeconomics; Edward Elgar Publishing: Glos, UK, 2021; pp. 139–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokoszka, P.; Reimherr, M. Determining the order of the functional autoregressive model. J. Time Ser. Anal. 2013, 34, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocioni, P. Can State Aid Policy Become more Economic Friendly? World Compet. 2006, 29, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakimowicz, A.; Rzeczkowski, D. Do barriers to innovation impact changes in innovation activities of firms during business cycle? The effect of the Polish green island. Equilibrium 2019, 14, 631–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, A.; Doig, A. Researching Ethics for Public Service Organizations: The View From Europe. Public Integr. 2006, 8, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bompard, E.; Carpignano, A.; Erriquez, M.; Grosso, D.; Pession, M.; Profumo, F. National energy security assessment in a geopolitical perspective. Energy 2017, 130, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruyt, B.; van Vuuren, D.P.; de Vries, H.J.M.; Groenenberg, H. Indicators for energy security. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 2166–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokicki, T.; Perkowska, A. Changes in Energy Supplies in the Countries of the Visegrad Group. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augutis, J.; Krikštolaitis, R.; Martišauskas, L.; Pečiulytė, S.; Žutautaitė, I. Integrated energy security assessment. Energy 2017, 138, 890–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Delays | p(LR) | AIC | BIC | HQC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ------ | −7.445717 * | −7.233908 * | −7.678072 * |

| 2 | 0.00049 | 8.462832 | −8.220764 | −8.728380 |

| 3 | 0.03527 | −8.706015 | −8.433688 | −9.004757 |

| Specification | Factor | Standard Error | Student’s t | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | −0.950297 | 0.239601 | −3.966 | 0.0041 | *** |

| Share of unprofitable companies_1 | 0.824550 | 0.127044 | 6.490 | 0.0002 | *** |

| The value of goods and materials sold to net sales revenue_1 | 2.61034 | 0.592742 | 4.404 | 0.0023 | *** |

| EBIT margin_1 | −1.30258 | 0.558907 | −2.331 | 0.0481 | ** |

| PKB_1 | −0.197481 | 0.0413729 | −4.773 | 0.0014 | *** |

| Specification | Factor | Standard Error | Student’s t | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | −0.820125 | 0.262679 | −3.122 | 0.0142 | ** |

| Share of companies with delays in repayment of credits and loans exceeding 90 days_1 | 0.619460 | 0.133600 | 4.637 | 0.0017 | *** |

| The value of goods and materials sold to net sales revenue_1 | 2.42612 | 0.738381 | 3.286 | 0.0111 | ** |

| Oil WT_1 | 0.000289509 | 0.000261396 | 1.9108 | 0.08002 | * |

| CPI_1 | 0.497124 | 0.262320 | 1.895 | 0.0947 | * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zając, A.; Balina, R.; Kowalski, D. Financial and Economic Stability of Energy Sector Enterprises as a Condition for Poland’s Energy Security—Legal and Economic Aspects. Energies 2023, 16, 1442. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16031442

Zając A, Balina R, Kowalski D. Financial and Economic Stability of Energy Sector Enterprises as a Condition for Poland’s Energy Security—Legal and Economic Aspects. Energies. 2023; 16(3):1442. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16031442

Chicago/Turabian StyleZając, Adam, Rafał Balina, and Dariusz Kowalski. 2023. "Financial and Economic Stability of Energy Sector Enterprises as a Condition for Poland’s Energy Security—Legal and Economic Aspects" Energies 16, no. 3: 1442. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16031442

APA StyleZając, A., Balina, R., & Kowalski, D. (2023). Financial and Economic Stability of Energy Sector Enterprises as a Condition for Poland’s Energy Security—Legal and Economic Aspects. Energies, 16(3), 1442. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16031442