A New Method of Building Envelope Thermal Performance Evaluation Considering Window–Wall Correlation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Room Comprehensive Thermal Performance Indexes

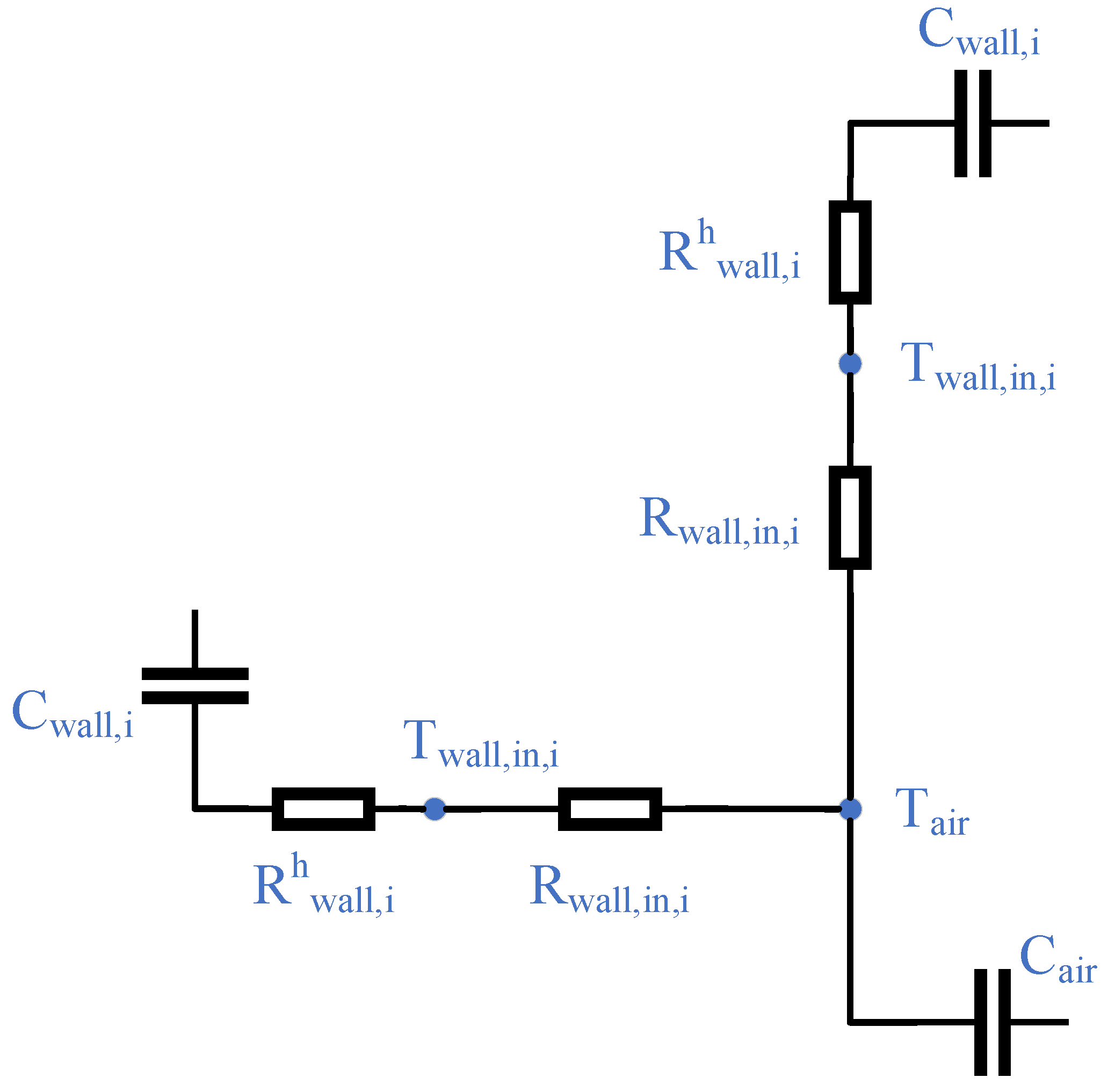

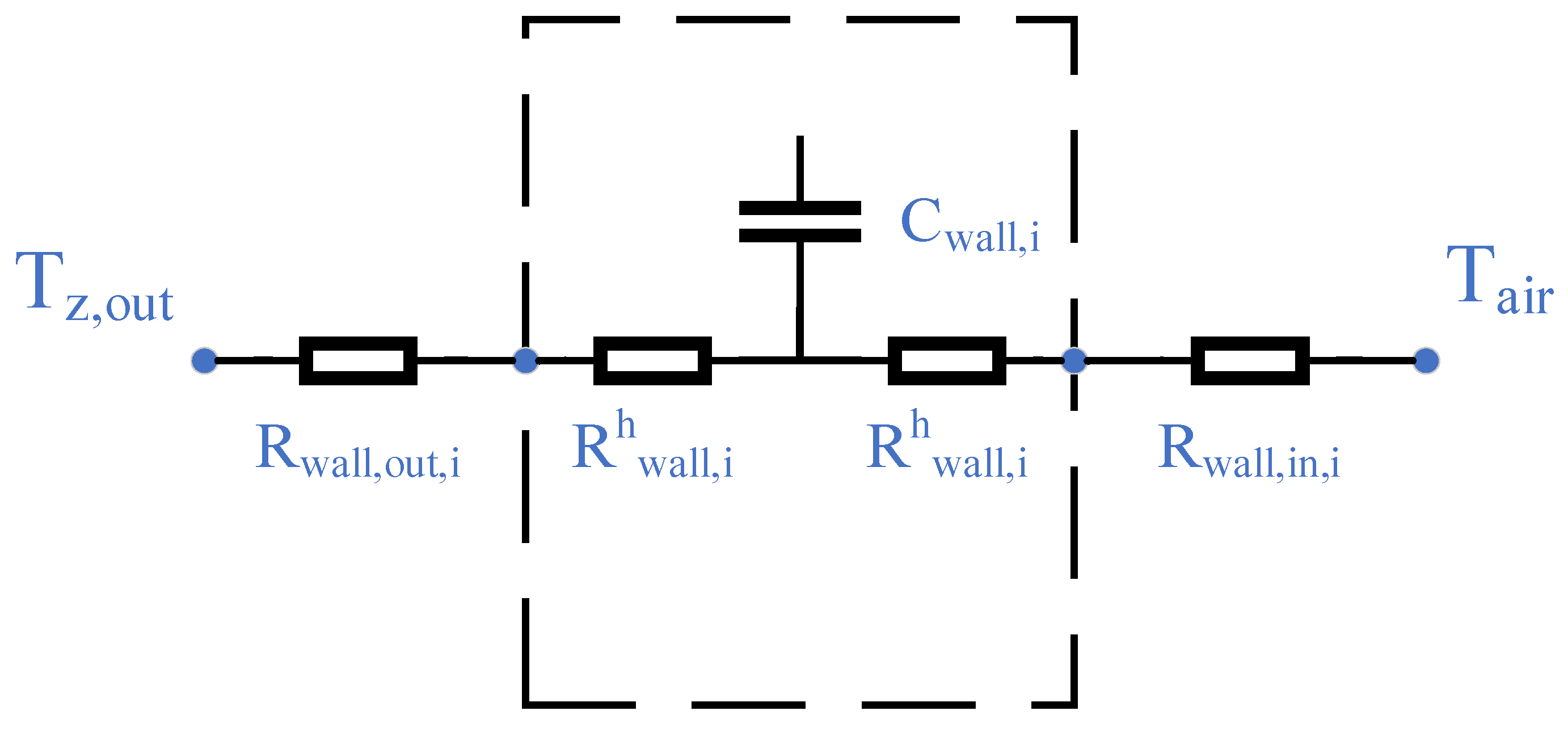

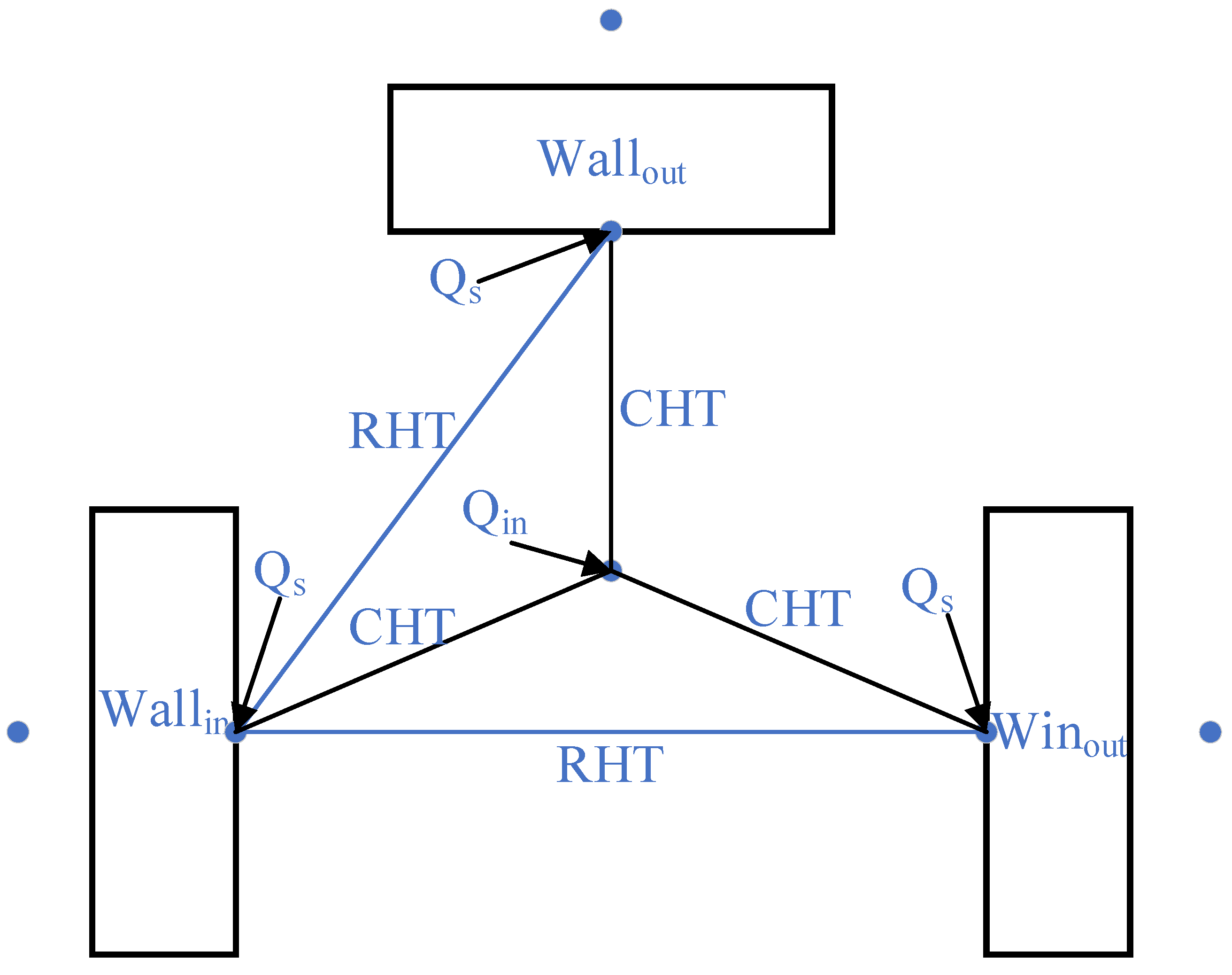

2.1.1. Room Heat Transfer RC Model

- (a)

- The indoor air temperature is uniformly distributed and treated as a single node;

- (b)

- Neglecting the heat capacity of exterior windows;

- (c)

- The envelope structure consists of homogeneous materials, and the physical parameters do not vary with temperature;

- (d)

- The surface of the envelope structure is a diffuse gray surface;

- (e)

- Neglecting considering latent heat transfer and its influence;

- (f)

- No air conditioning in the room;

- (g)

- The room’s envelope consists of one exterior wall and five interior walls (including the ceiling and floor).

2.1.2. Room Comprehensive Thermal Resistance

2.1.3. Room Comprehensive Thermal Capacity

2.1.4. Room Comprehensive Thermal Performance Indexes Solution

- (1)

- Comprehensive outdoor air temperature

- (2)

- Adjacent room air temperature

- (3)

- Surface heat transfer thermal resistance

- (4)

- Thermal conduction resistance

- (5)

- Surface thermal radiation resistance

- (6)

- Space radiation thermal resistance between surfaces

- (7)

- Indoor heat gain

- (8)

- Solar heat gain

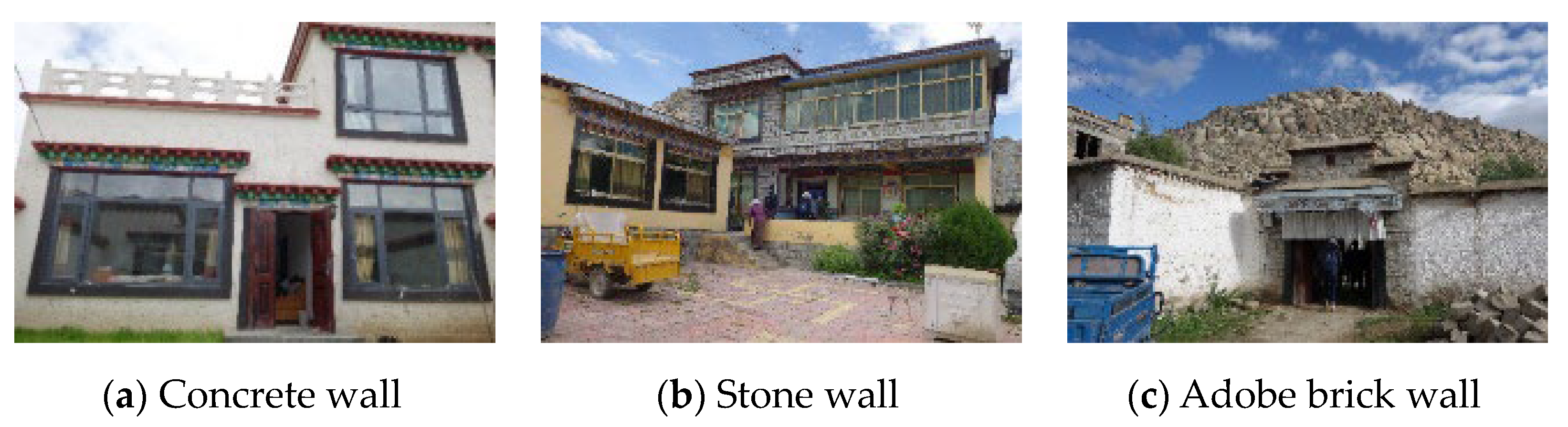

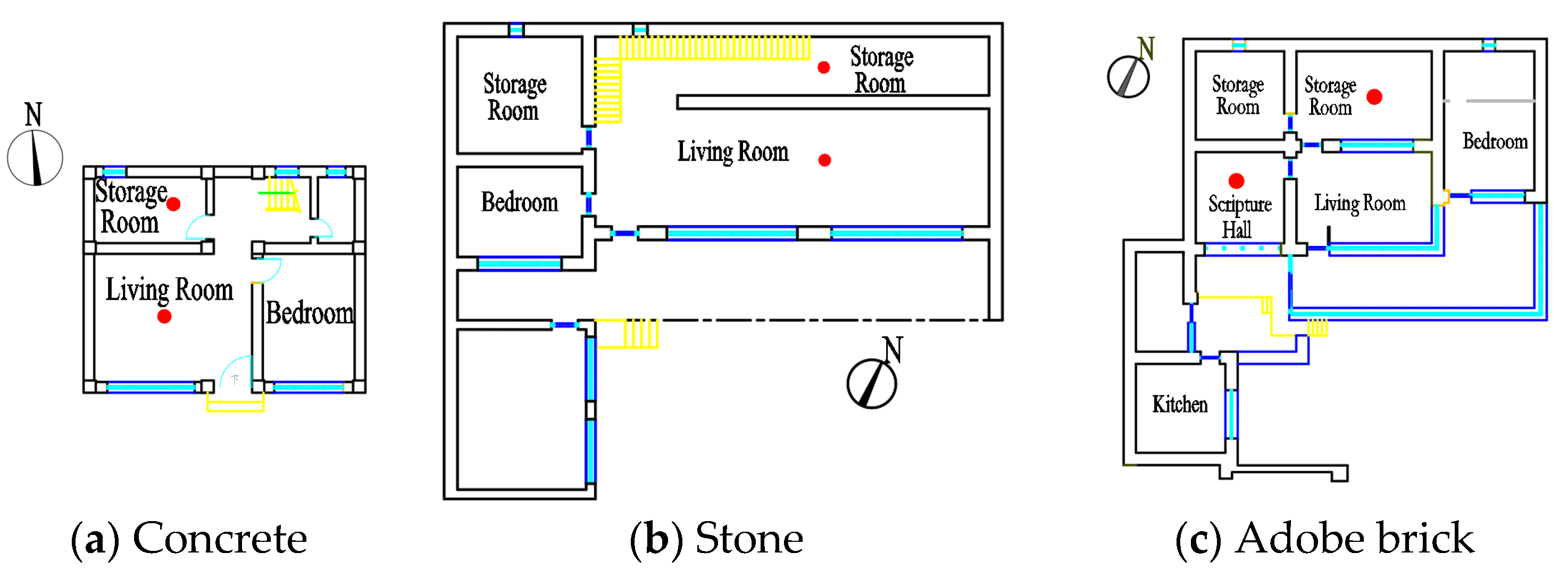

2.2. Lhasa Dwelling Field Studies

Test Methods and Instrumentation

2.3. Numerical Modeling for Room Comprehensive Thermal Performance Indexes Validity

2.3.1. Case Description

- (1)

- Meteorological condition

- (2)

- Heat transfer-related parameters

- (3)

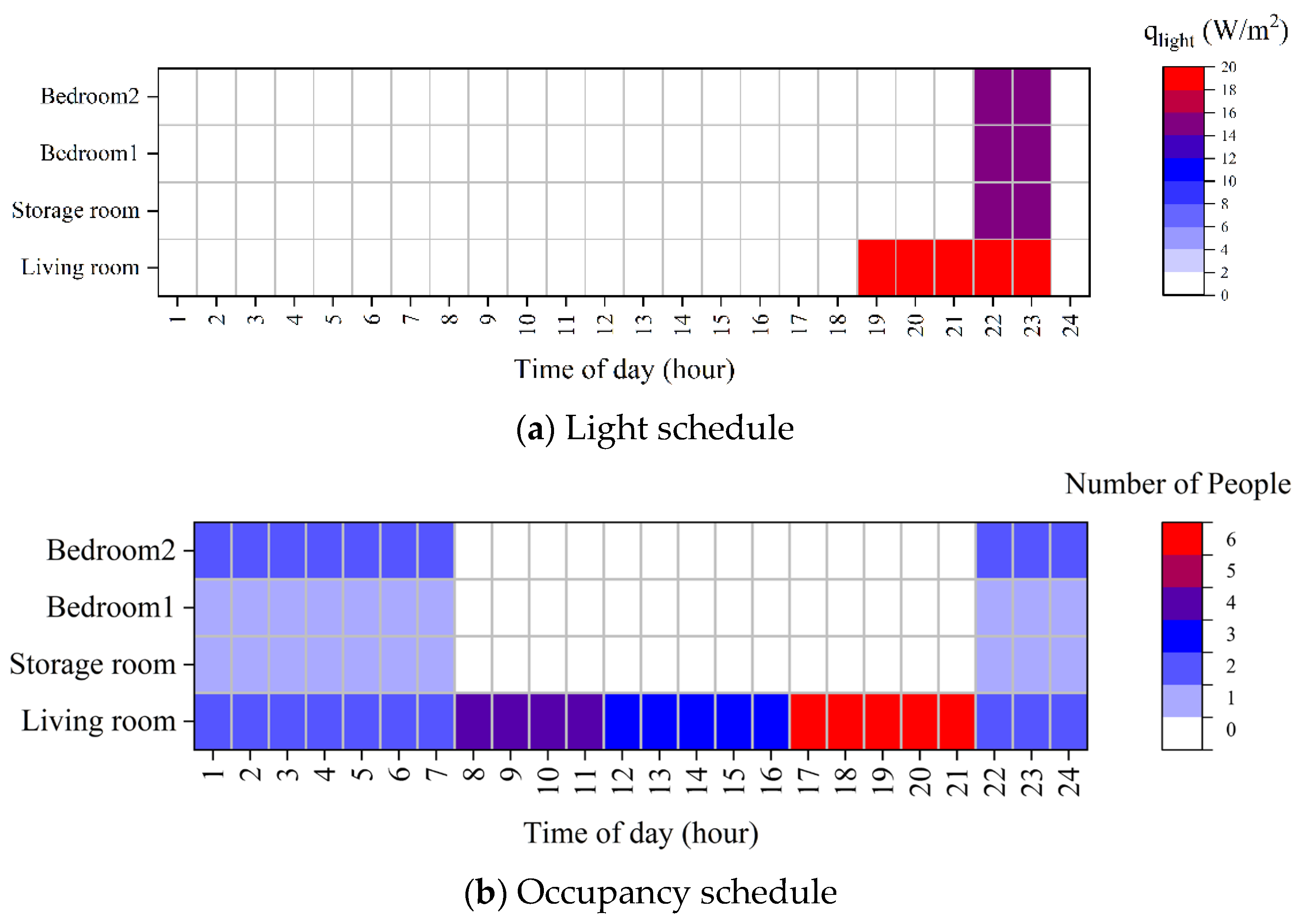

- Light and occupancy schedules

- (4)

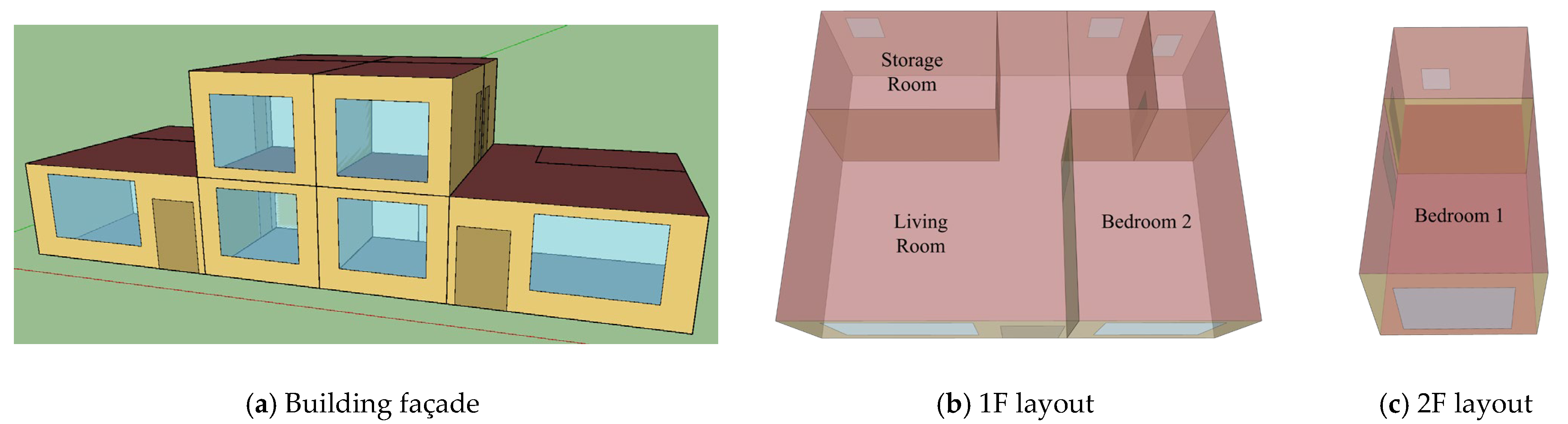

- Basic building information

2.3.2. Evaluating Indicators

2.4. Index-Based Lhasa Residential Building Envelope Thermal Performance Study

3. Result and Discussion

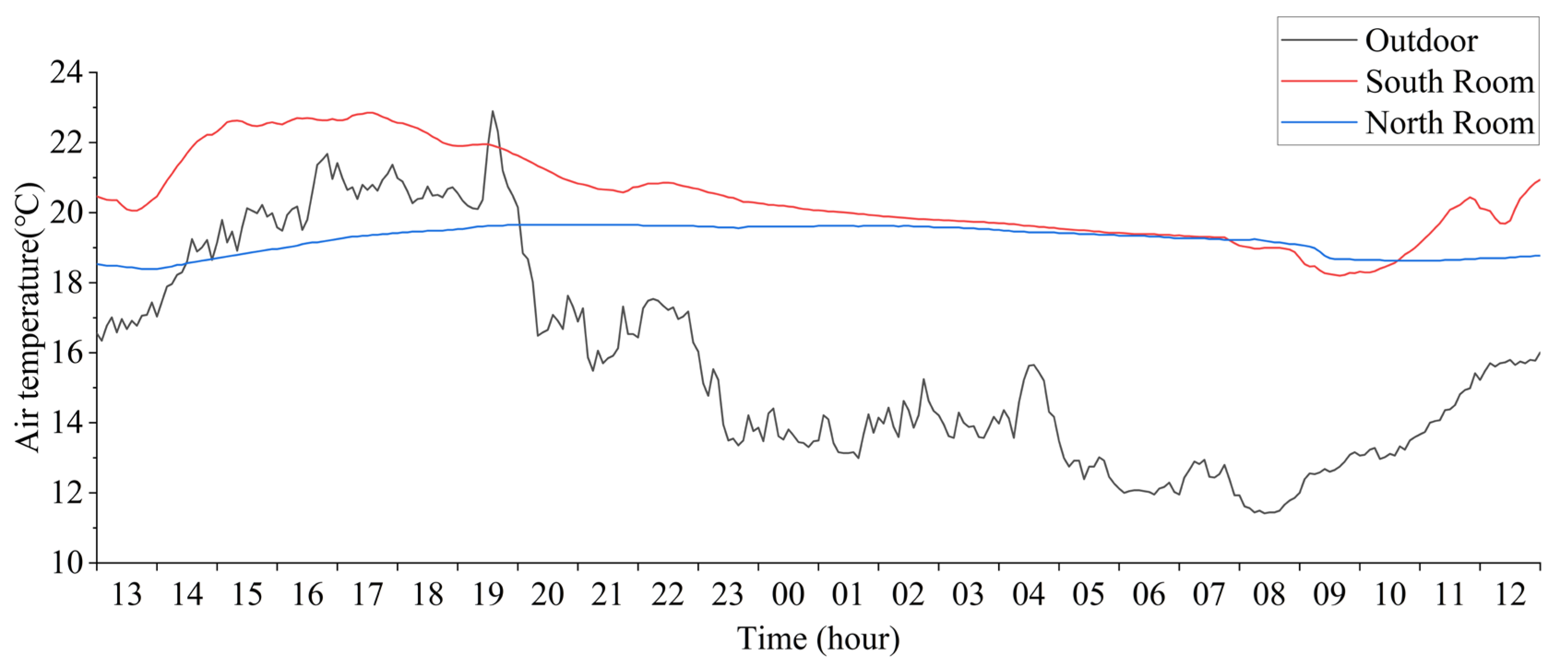

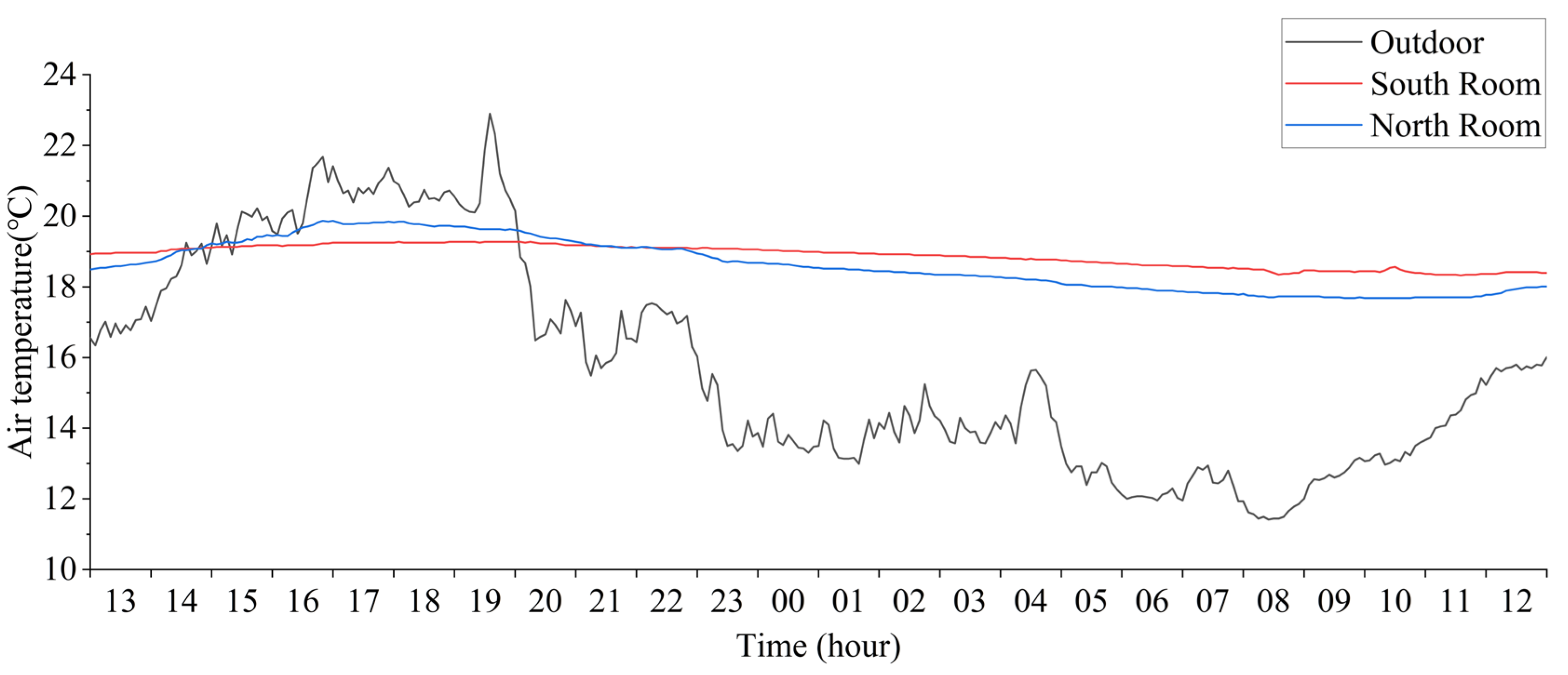

3.1. Field Test Result

3.2. Thermal Performance Indexes Validity

3.2.1. Model Verification

3.2.2. Index Validity Analysis

3.3. Index-Based Lhasa Residential Building Envelope Performance Evaluation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Comprehensive outdoor air temperature [°C] | |

| Adjacent room air temperature [°C] | |

| Wall interior equivalent temperature [°C] | |

| Wall internal surface temperature [°C] | |

| Window temperature [°C] | |

| Indoor air temperature [°C] | |

| Building external envelope equivalent temperature difference [°C] | |

| Building internal envelope equivalent temperature difference [°C] | |

| Exterior wall internal surface effective radiation [W] | |

| Interior wall internal surface effective radiation [W] | |

| Window internal surface effective radiation [W] | |

| Wall external surface thermal resistance [K/W] | |

| Wall equivalent thermal conduction resistance [K/W] | |

| Wall internal surface thermal resistance [K/W] | |

| Window external surface thermal resistance [K/W] | |

| Window thermal conduction resistance [K/W] | |

| Window internal surface thermal resistance [K/W] | |

| Exterior wall internal surface thermal radiation resistance [K/W] | |

| Interior wall internal surface thermal radiation resistance [K/W] | |

| Window internal surface thermal radiation resistance [K/W] | |

| , | Space radiation thermal resistance [K/W] |

| Exterior envelope comprehensive thermal resistance [m2·K/W] | |

| Interior envelope comprehensive thermal resistance [m2·K/W] | |

| Exterior envelope equivalent heat transfer coefficient [W/(m2·K)] | |

| Interior envelope equivalent heat transfer coefficient [W/(m2·K)] | |

| Window overall heat transfer coefficient [W/(m2·K)] | |

| Exterior wall area [m2] | |

| Interior wall area [m2] | |

| Window area [m2] | |

| Room volume [m3] | |

| Room solar heat gain through the window [W] | |

| Envelope internal surface solar heat gain [W] | |

| Building internal heat gain [W] | |

| Room heat gain [W] | |

| Exterior envelope heat gain [W] | |

| Interior envelope heat gain [W] | |

| Exterior wall thermal capacity [J/K] | |

| Interior wall thermal capacity [J/K] | |

| Indoor air thermal capacity [J/K] | |

| Room thermal capacity [J/K] | |

| Room comprehensive thermal capacity per unit volume [kJ/(m3·K)] | |

| Outdoor solar radiation intensity [W/m2] | |

| Window transmittance |

References

- Perez-Lombard, L.; Ortiz, J.; Pout, C. A review on buildings energy consumption information. Energy Build. 2008, 40, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhamare, D.K.; Rathod, M.K.; Banerjee, J. Proposal of a unique index for selection of optimum phase change material for effective thermal performance of a building envelope. Sol. Energy 2021, 218, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastide, A.; Lauret, P.; Garde, F.; Boyer, H. Building energy efficiency and thermal comfort in tropical climates—Presentation of a numerical approach for predicting the percentage of well-ventilated living spaces in buildings using natural ventilation. Energy Build. 2006, 38, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaras, C.A. The role of thermal mass on the cooling load of buildings. An overview of computational methods. Energy Build. 1996, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.Z.; Chou, S.K.; Bong, T.Y. Building simulation: An overview of developments and information sources. Build. Environ. 2000, 35, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Meng, Q.; Cai, J.; Yoshino, H.; Mochida, A. Applying support vector machine to predict hourly cooling load in the building. Appl. Energy 2009, 86, 2249–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Xiao, F.; Zhao, Y. A short-term building cooling load prediction method using deep learning algorithms. Appl. Energy 2017, 195, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, G.; Knight, I. Small power equipment loads in UK office environments. Energy Build. 2005, 37, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, J.; Robinson, D.; Morel, N.; Scartezzini, J.L. A generalised stochastic model for the simulation of occupant presence. Energy Build. 2008, 40, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, S.S.K.; Lee, E.W.M. A study of the importance of occupancy to building cooling load in prediction by intelligent approach. Energy Convers. Manag. 2011, 52, 2555–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Deb, C. Envelope design for low-energy buildings in the tropics: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 186, 113650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philokyprou, M.; Michael, A.; Malaktou, E.; Savvides, A. Environmentally responsive design in Eastern Mediterranean. The case of vernacular architecture in the coastal, lowland and mountainous regions of Cyprus. Build. Environ. 2017, 111, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benslimane, N.; Biara, R.W. The urban sustainable structure of the vernacular city and its modem transformation: A case study of the popular architecture in the saharian Region. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Technologies and Materials for Renewable Energy, Environment and Sustainability (TMREES), Athens, Greece, 19–21 September 2018; pp. 1241–1252. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, A.; Saghafi, M.R.; Tahbaz, M.; Nasrollahi, F. The study of climate-responsive solutions in traditional dwellings of Bushehr City in Southern Iran. J. Build. Eng. 2018, 16, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J. Architecture indigenous to extreme climates. Energy Build. 1996, 23, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almssad, A.; Almusaed, A. Environmental reply to vernacular habitat conformation from a vast areas of Scandinavia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 48, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijal, H.B. Thermal adaptation of buildings and people for energy saving in extreme cold climate of Nepal. Energy Build. 2021, 230, 110551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motealleh, P.; Zolfaghari, M.; Parsaee, M. Investigating climate responsive solutions in vernacular architecture of Bushehr city. HBRC J. 2018, 14, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzone, A. Thermal comfort and cooling strategies in the Brazilian Amazon. An assessment of the concept of fuel poverty in tropical climates. Energy Policy 2020, 139, 111256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badescu, V.; Sicre, B. Renewable energy for passive house heating Part I. Building description. Energy Build. 2003, 35, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Optimization for Building Control Systems of a School Building in Passive House Standard. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Kuckelkorn, J.; Zhao, F.-Y.; Spliethoff, H.; Lang, W. A state of art of review on interactions between energy performance and indoor environment quality in Passive House buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 72, 1303–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hee, W.J.; Alghoul, M.A.; Bakhtyar, B.; Elayeb, O.; Shameri, M.A.; Alrubaih, M.S.; Sopian, K. The role of window glazing on daylighting and energy saving in buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 42, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A. Diffuse transmission dominant smart and advanced windows for less energy-hungry building: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 64, 105604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratia, E.; De Herde, A. Design of low energy office buildings. Energy Build. 2003, 35, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Hewitt, N.; Griffiths, P. Zero carbon buildings refurbishment—A Hierarchical pathway. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 3229–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Masi, R.F.; Festa, V.; Gigante, A.; Ruggiero, S.; Vanoli, G.P. The role of windows on building performance under current and future weather conditions of European climates. Energy Build. 2023, 292, 113177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, F.A.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, G.; Peng, C. An investigation of optimal window-to-wall ratio based on changes in building orientations for traditional dwellings. Sol. Energy 2020, 195, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrecht, T.P.; Premrov, M.; Leskovar, V.Z. Influence of the orientation on the optimal glazing size for passive houses in different European climates (for non-cardinal directions). Sol. Energy 2019, 189, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafian, T.; Moazzen, N. The impact of glazing ratio and window configuration on occupants’ comfort and energy demand: The case study of a school building in Eskisehir, Turkey. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 47, 101483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroglou, T.; Meir, I.A.; Theodosiou, T. Quantifying Energy Consumption in Skyscrapers of Various Heights. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2017, 38, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroglou, S.; Meir, I.A.; Theodosiou, T. Energy Efficiency of a High-Rise Office Building in the Mediterranean Climate with the Use of Different Envelope Scenarios. In Smart and Sustainable Cities and Buildings; Roggema, R., Roggema, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 651–661. [Google Scholar]

- Arnaoutakis, G.E.; Katsaprakakis, D.A. Energy Performance of Buildings with Thermochromic Windows in Mediterranean Climates. Energies 2021, 14, 6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, B.; Norford, L.; Pigeon, G.; Britter, R. A resistance-capacitance network model for the analysis of the interactions between the energy performance of buildings and the urban climate. Build. Environ. 2012, 54, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunsola, O.T.; Song, L. Application of a simplified thermal network model for real-time thermal load estimation. Energy Build. 2015, 96, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara, E.Á.R.; de la Flor, F.J.S.; Domínguez, S.Á.; Félix, J.L.M.; Lissén, J.M.S. A new analytical approach for simplified thermal modelling of buildings: Self-Adjusting RC-network model. Energy Build. 2016, 130, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Chen, J.; Su, T.; Liu, X.; Hu, Y.; Luo, Q.; Luo, L. An RC-network model in the frequency domain for radiant floor heating coupled with envelopes. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 225, 109617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JGJ/T 260-2011; Technical Regulations for Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning Engineering Testing. China Building Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2011.

- JGJ/T 132-2009; Energy Efficiency Testing Standards for Residential Buildings. China Building Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2009.

- GB/T 31156-2014; Total Solar Energy Resources Measurement Radiation. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2014.

- Stavrakakis, G.M.; Katsaprakakis, D.A.; Damasiotis, M. Basic Principles, Most Common Computational Tools, and Capabilities for Building Energy and Urban Microclimate Simulations. Energies 2021, 14, 6707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, G.J.P. Study on Construction System of Low Energy Consumption Residential Buildings in Tibet Plateau. Ph.D. Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tüysüz, F.; Sözer, H. Calibrating the building energy model with the short term monitored data: A case study of a large-scale residential building. Energy Build. 2020, 224, 110207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Liu, T.; Cao, T.; Hwang, Y.; Radermacher, R. Comparing deep learning models for multi energy vectors prediction on multiple types of building. Appl. Energy 2021, 301, 117486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.; Kim, B.S. Prediction of building power consumption using transfer learning-based reference building and simulation dataset. Energy Build. 2022, 258, 111717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, T. A synchronous prediction method for hourly energy consumption of abnormal monitoring branch based on the data-driven. Energy Build. 2022, 260, 111940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weather Data|Energy Plus. Available online: https://energyplus.net/weather (accessed on 1 October 2018).

| Category | Parameter |

|---|---|

| Temperature Node | , , , , , , |

| Radiance Node | , , |

| Thermal Resistance | |

| Indoor Heat Gain | |

| Solar Heat Gain |

| Parameter | Instrument | Range | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature and Humidity | HOBO U12-011 | −20~70 °C, 0–95% | 0.5 °C, 5% RH |

| Outdoor Temperature | HOBO H21-USB | −40~+75 °C | ±0.21 °C |

| Outdoor Humidity | 0~100% | ±2.5% | |

| Total Solar Radiation Intensity | 0~1680 W/m2 | ±10 W/m2 |

| Material | Thermal Conductivity [W/(m·K)] | Thermal Storage Coefficient [W/(m2·K)] | Specific Heat Capacity [kJ/(kg·K)] | Density [kg/m3] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stone | 2.45 | 19.26 | 0.82 | 2320 |

| Crushed concrete | 1.84 | 16.58 | 0.75 | 2100–2600 |

| Clay | 0.70 | 9.24 | 1.05 | 1600 |

| EPS | 0.028 | 0.46 | 2.1 | 50 |

| Parameter | Case 1 (Benchmark Case) | Case 2 | Case 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjacent room air temperature [°C] | 18.0 | 18.0 | 18.0 |

| Comprehensive outdoor air temperature [°C] | 48.7 | 48.7 | 48.7 |

| Window overall heat transfer coefficient [W/(m2·K)] | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.7 |

| Outdoor solar radiation intensity [W/m2] | 768 | 768 | 768 |

| Window transmittance | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.91 |

| Window–wall ratio | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| External wall thickness [m] | 0.34 | 0.52 | 0.46 |

| Interior wall thickness [m] | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| External wall Thermal conductivity [W/(m·K)] | 0.18 | 0.70 | 2.45 |

| Interior wall Thermal conductivity [W/(m·K)] | 1.84 | 1.84 | 1.84 |

| External wall density [kg/m3] | 2074 | 1600 | 2320 |

| Interior wall density [kg/m3] | 2344 | 2215 | 2026 |

| External envelope comprehensive thermal resistance [m2·K/W] | 3.46 | 3.46 | 3.46 |

| Interior envelope comprehensive thermal resistance [m2·K/W] | 7.23 | 7.23 | 7.23 |

| Room comprehensive thermal capacity per unit volume [kJ/(m3·K)] | 853 | 853 | 853 |

| Wall | Construction (From Outside to Inside) | Thermal Conductivity [W/(m·K)] | Thermal Inertia Index | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crushed concrete | External wall | 40 mm EPS + 300 mm concrete | 0.57 | 3.28 |

| Interior wall | 300 mm concrete | 3.06 | 2.62 | |

| Clay | External wall | 25 mm mud + 500 mm clay + 25 mm mud | 1.01 | 7.28 |

| Interior wall | 25 mm mud + 500 mm clay + 25 mm mud | 1.01 | 7.28 | |

| Stone | External wall | 550 mm stone | 2.54 | 4.32 |

| Interior wall | 550 mm stone | 2.54 | 4.32 | |

| Room | MBE | CVRMSE |

|---|---|---|

| Living room | 5.79% | 11.48% |

| Storage room | 8.25% | 17.91% |

| Bedroom1 | 7.12% | 13.89% |

| Bedroom2 | 9.95% | 15.30% |

| Room | MBE | CVRMSE |

|---|---|---|

| Living room | 2.56% | 1.44% |

| Storage room | 3.67% | 2.92% |

| Bedroom1 | 1.53% | 0.39% |

| Bedroom2 | 1.42% | 0.42% |

| Room | MBE | CVRMSE |

|---|---|---|

| Living room | 0.40% | 0.06% |

| Storage room | 0.57% | 0.09% |

| Bedroom1 | 0.62% | 0.07% |

| Bedroom2 | 0.28% | 0.02% |

| Parameter | Concrete Building | Stone Building | Adobe Brick Building |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjacent room air temperature [°C] | 18.0 | 18.0 | 18.0 |

| Comprehensive outdoor air temperature [°C] | 48.7 | 48.7 | 48.7 |

| Window overall heat transfer coefficient [W/(m2·K)] | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Outdoor solar radiation intensity [W/m2] | 768 | 768 | 768 |

| Window transmittance | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.87 |

| Window–wall ratio | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.40 |

| External wall thickness [m] | 0.34 | 0.55 | 0.50 |

| Interior wall thickness [m] | 0.30 | 0.55 | 0.50 |

| External wall thermal conductivity [W/(m·K)] | 0.18 | 2.45 | 0.93 |

| Interior wall thermal Conductivity [W/(m·K)] | 1.84 | 2.45 | 0.93 |

| External wall density [kg/m3] | 2074 | 2640 | 1600 |

| Interior wall density [kg/m3] | 2344 | 2640 | 1600 |

| Index | Concrete Building | Stone Building | Adobe Brick Building |

|---|---|---|---|

| External wall comprehensive thermal resistance [m2·K/W] | 3.46 | 1.68 | 5.90 |

| Interior wall comprehensive thermal resistance [m2·K/W] | 7.23 | 7.82 | 21.05 |

| Room comprehensive thermal capacity per unit volume [kJ/(m3·K)] | 853 | 1170 | 1744 |

| Parameter | Concrete Building | Stone Building | Adobe Brick Building |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjacent room air temperature [°C] | −3.1 | −3.1 | −3.1 |

| Comprehensive outdoor air temperature [°C] | 28.1 | 28.1 | 28.1 |

| Window overall heat transfer coefficient [W/(m2·K)] | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Outdoor solar radiation intensity [W/m2] | 779 | 779 | 779 |

| Window transmittance | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.87 |

| Window–wall ratio | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.40 |

| External wall thickness [m] | 0.34 | 0.55 | 0.50 |

| Interior wall thickness [m] | 0.30 | 0.55 | 0.50 |

| External wall thermal conductivity [W/(m·K)] | 0.18 | 2.45 | 0.93 |

| Interior wall thermal Conductivity [W/(m·K)] | 1.84 | 2.45 | 0.93 |

| External wall density [kg/m3] | 2074 | 2640 | 1600 |

| Interior wall density [kg/m3] | 2344 | 2640 | 1600 |

| Index | Concrete Building | Stone Building | Adobe Brick Building |

|---|---|---|---|

| External wall comprehensive thermal resistance [m2·K/W] | 3.27 | 1.58 | 5.69 |

| Interior wall comprehensive thermal resistance [m2·K/W] | 6.83 | 7.45 | 20.12 |

| Room comprehensive thermal capacity per unit volume [kJ/(m3·K)] | 853 | 1170 | 1744 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Z.; Si, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Feng, X. A New Method of Building Envelope Thermal Performance Evaluation Considering Window–Wall Correlation. Energies 2023, 16, 6927. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16196927

Li Z, Si Y, Zhao Q, Feng X. A New Method of Building Envelope Thermal Performance Evaluation Considering Window–Wall Correlation. Energies. 2023; 16(19):6927. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16196927

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Zhengrong, Yang Si, Qun Zhao, and Xiwen Feng. 2023. "A New Method of Building Envelope Thermal Performance Evaluation Considering Window–Wall Correlation" Energies 16, no. 19: 6927. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16196927

APA StyleLi, Z., Si, Y., Zhao, Q., & Feng, X. (2023). A New Method of Building Envelope Thermal Performance Evaluation Considering Window–Wall Correlation. Energies, 16(19), 6927. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16196927