Identifying Themes in Energy Poverty Research: Energy Justice Implications for Policy, Programs, and the Clean Energy Transition

Abstract

:1. Introduction

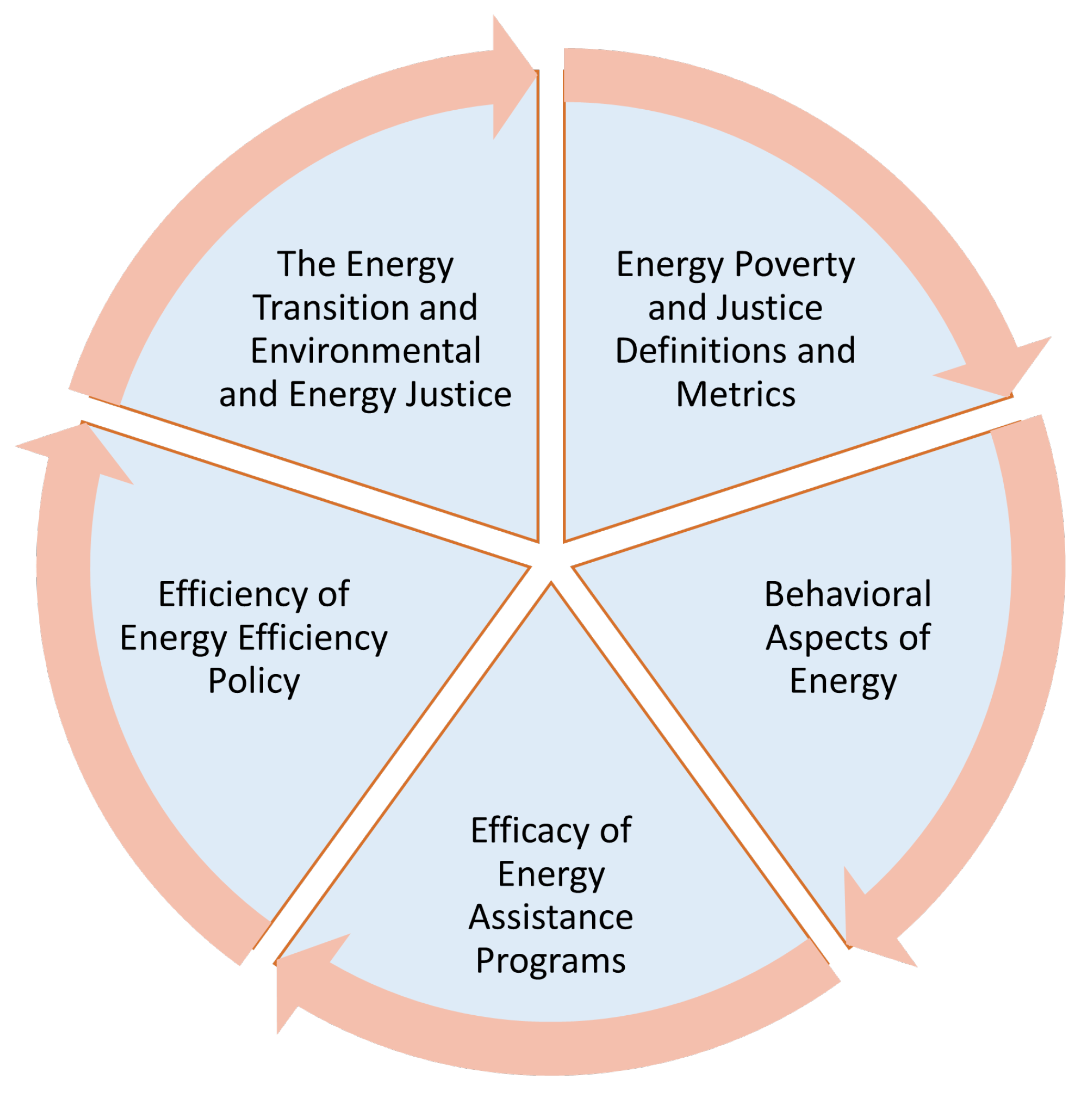

2. Background on Energy Poverty and Energy Justice

3. Energy Poverty and Justice Definitions and Metrics

4. Behavioral Aspects of Energy Poverty

5. Efficacy of Energy Assistance Programs

6. Efficacy of Energy Policy

7. The Clean Energy Transition and Energy Justice

- Community engagement where communities that are marginalized, are actively involved in decision-making processes related to energy transition. Their input and feedback can guide the development of energy projects that meet their needs and respect their rights.

- Affordability—The cost of new energy technologies can be a barrier to access for low-income households. Policies and initiatives should aim to make renewable energy affordable for all to ensure broad adoption.

- Job Creation—The energy transition can create jobs in the renewable energy sector. Training and educational programs can ensure that these opportunities are accessible to people from diverse backgrounds, contributing to social inclusivity.

- Energy Justice—Energy transition should aim to address historical inequities in energy access and the impacts of energy production. This involves reducing pollution in marginalized communities and ensuring fair access to the benefits of renewable energy.

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- González-Eguino, M. Energy poverty: An overview. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednar, D.J.; Reames, T.G. Recognition of and response to energy poverty in the United States. Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontokosta, C.E.; Reina, V.J.; Bonczak, B. Energy Cost Burdens for Low-Income and Minority Households. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2020, 86, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ash, M.; Baker, E.; Tuominen, M.; Venkataraman, D.; Burke, M.; Ash, M.; Baker, E.; Tuominen, M.; Venkataraman, D.; Burke, M.; et al. White paper: Research Challenges at the Intersection of Energy and Equity in the Energy Transition. Eti Rep. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DOE. Office of Energy Justice Policy and Analysis|Department of Energy. 2023. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/diversity/office-energy-justice-policy-and-analysis (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Ravikumar, A.P.; Baker, E.; Bates, A.; Nock, D.; Venkataraman, D.; Johnson, T.; Ash, M.; Attari, S.Z.; Bowie, K.; Carley, S.; et al. Enabling an equitable energy transition through inclusive research. Nat. Energy 2022, 8, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzarovski, S.; Petrova, S.; Sarlamanov, R. Energy poverty policies in the EU: A critical perspective. Energy Policy 2012, 49, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission, E. Powering a Climate-Neutral Economy: Commission Sets out Plans for the Energy System of the Future and Clean Hydrogen. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_1259 (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Sovacool, B.K.; Dworkin, M.H. Global Energy Justice: Problems, Principles, and Practices; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 1–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, K.; McCauley, D.; Forman, A. Energy justice: A policy approach. Energy Policy 2017, 105, 631–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschhausen, C.V.; Waelde, T.W. The End of Transition: An Institutional Interpretation of Energy Sector Reform in Eastern Europe and the CIS. Most. Econ. Policy Transit. Econ. 2001, 11, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, K.; McCauley, D.; Heffron, R.; Stephan, H.; Rehner, R. Energy justice: A conceptual review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 11, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, D.A.; Heffron, R.J.; Stephan, H.; Jenkins, K. Advancing Energy Justice: The Triumvirate of Tenets. Int. Energy Law Rev. 2013, 32, 107–110. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, S.; Mccauley, D. Energy Research & Social Science Framing energy justice: Perspectives from activism and advocacy. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Alier, J. Mining conflicts, environmental justice, and valuation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2001, 86, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, G. Beyond distribution and proximity: Exploring the multiple spatialities of environmental justice. Antipode 2009, 41, 614–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drehobl, A.; Ross, L. Lifting the High Energy Burden in America’s Largest Cities: How Energy Efficiency Can Improve Low-Income and Underserved Communities. 2016. Available online: https://www.aceee.org/research-report/u1602 (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Administration, U.E.I. What’s New in How We Use Energy at Home: Results from EIA’s 2015 Residential Energy Consumption Survey (RECS). Indep. Stat. Anal. Anal. 2017. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/consumption/residential/reports/2015/overview/pdf/whatsnew_home_energy_use.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Cong, S.; Nock, D.; Qiu, Y.L.; Xing, B. Unveiling hidden energy poverty using the energy equity gap. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, D.; Levin, T.; Baker, E. Changing the policy paradigm: A benefit maximization approach to electricity planning in developing countries. Appl. Energy 2020, 264, 114583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednar, D.J.; Reames, T.G.; Keoleian, G.A. The intersection of energy and justice: Modeling the spatial, racial/ethnic and socioeconomic patterns of urban residential heating consumption and efficiency in Detroit, Michigan. Energy Build. 2017, 143, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reames, T.G. Exploring Residential Rooftop Solar Potential in the United States by Race and Ethnicity. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortier, M.O.P.; Teron, L.; Reames, T.G.; Munardy, D.T.; Sullivan, B.M. Introduction to evaluating energy justice across the life cycle: A social life cycle assessment approach. Appl. Energy 2019, 236, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, H.D.; Roy, J.; Azevedo, I.M.L.; Chakravarty, D.; Dasgupta, S.; Can, S.D.L.R.D.; Druckman, A.; Fouquet, R.; Grubb, M.; Lin, B.; et al. Annual Review of Environment and Resources Energy Efficiency: What Has Research Delivered in the Last 40 Years? Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2021, 6, 135–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raissi, S.; Reames, T.G. “If we had a little more flexibility.” perceptions of programmatic challenges and opportunities implementing government-funded low-income energy efficiency programs. Energy Policy 2020, 147, 111880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivo, G. Unequal access to energy efficiency in US multifamily rental housing: Opportunities to improve. Build. Res. Inf. 2014, 42, 551–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.C.; Harmon, D.; Kemabonta, T. Energy and Emissions Savings Potential of Renewable Thermal Technologies in Houston, Texas. 2021. Available online: https://cbey.yale.edu/research/energy-and-emissions-savings-potential-of-renewable-thermal-technologies-in-houston-texas (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Harmon, D.; Jones, E.; Moss, J.; Wolfe, E. Pathways for Reducing Energy Burdens in Harris County. In Study on Energy Efficiency in Buildings; 2020; p. 13. Available online: https://www.aceee.org/files/proceedings/2020/event-data/indexes (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Glasgo, B.; Khan, N.; Azevedo, I.L. Simulating a residential building stock to support regional efficiency policy. Appl. Energy 2020, 261, 114223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekanye, O.G.; Davis, A.; Azevedo, I.L. Federal policy, local policy, and green building certifications in the U.S. Energy Build. 2020, 209, 109700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keady, W.; Panikkar, B.; Nelson, I.L.; Zia, A. Energy justice gaps in renewable energy transition policy initiatives in Vermont. Energy Policy 2021, 159, 112608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heleno, M.; Sigrin, B.; Popovich, N.; Heeter, J.; Figueroa, A.J.; Reiner, M.; Reames, T. Optimizing equity in energy policy interventions: A quantitative decision-support framework for energy justice. Appl. Energy 2022, 325, 119771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.C.; Leibowicz, B.D. Contributions of shared autonomous vehicles to climate change mitigation. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 72, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeter, J.; Reames, T. Incorporating energy justice into utility-scale photovoltaic deployment: A policy framework. Renew. Energy Focus 2022, 42, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, F.R.; Craig, M.; Jaramillo, P.; Bergés, M.; Severnini, E.; Loew, A.; Zhai, H.; Cheng, Y.; Nijssen, B.; Voisin, N.; et al. Climate-Induced Tradeoffs in Planning and Operating Costs of a Regional Electricity System. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 11204–11215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmallah, S.; Reames, T.G.; Spurlock, C.A. Frontlining energy justice: Visioning principles for energy transitions from community-based organizations in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 94, 102855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goforth, T.; Nock, D. Air pollution disparities and equality assessments of US national decarbonization strategies. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janicke, L.; Nock, D.; Surana, K.; Jordaan, S.M. Air pollution co-benefits from strengthening electric transmission and distribution systems. Energy 2023, 269, 126735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.; Bosetti, V.; Salo, A. Robust portfolio decision analysis: An application to the energy research and development portfolio problem. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 284, 1107–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurlock, C.A.; Elmallah, S.; Reames, T.G. Equitable deep decarbonization: A framework to facilitate energy justice-based multidisciplinary modeling. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 92, 102808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemabonta, T.; Jones, E.; Harmon, D.; Pittman, J. A New Approach to Developing Community Solar Projects for LMI Communities in ERCOT’s Competitive Electricity Markets. In Proceedings of the 2021 11th IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference, GHTC 2021, Seattle, WA, USA, 19–23 October 2021; pp. 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Article | Methods | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Cong et al., 2022 [19] Unveiling hidden energy poverty using the energy equity gap | Analyzed residential electricity consumption data and developed a new metric, “energy equity gap”. | The energy equity gap reveals a hidden aspect of energy poverty that is complementary to energy burden, showing that more than one metric is needed. |

| Nock et al., 2020 [20] Changing the policy paradigm: A benefit maximization approach to electricity planning in developing countries | (1) Formulated the expansion planning problem as a utility-maximization mixed-integer linear program. (2) Case study focused on a low-income country with limited electricity infrastructure. (3) Investigated investments that take consider stakeholder equity preferences using a Maximize Energy Access (MEA) model. | Considering equity metrics in planning resulted in a more interconnected grid with more transmission and decentralized energy sources and less centralized power. |

| Bednar et al., 2017 [21] The intersection of energy and justice: Modeling the spatial, racial/ethnic and socioeconomic patterns of urban residential heating consumption and efficiency in Detroit, Michigan | (1) Used GIS, bottom-up modelling, small-area estimation techniques. (2) Calculated energy consumption and Energy Use Intensity (EUI) using metrics such as: age of housing, income, demographics, expenditures, and more. | Revealed the importance of focusing on a comprehensive assessment of energy use rather than just consumption. A thorough energy assessment, including socioeconomic factors, may identify vulnerable households and effectively target energy efficiency programs. |

| Article | Methods | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Reames et al., 2021 [22] The Three E’s Revisited: How Do Community-Based Organizations Define Sustainable Communities and Their Role in Pursuit of? | Surveyed CBOS questions such as: (1) How do CBO leaders identify sustainable communities?; (2) How essential are each of the three sustainability pillars to their purpose? | These results illustrated how different terms and missions affected how CBOs understood and behaved to achieve their version of sustainable communities. For some energy poverty was essential but for others it did not matter at all. |

| Fortier et al., 2019 [23] Introduction to evaluating energy justice across the life cycle: A social life cycle assessment approach | (1) Created evaluation indicators for the social life cycle assessment to understand how different stakeholders behaved under different energy scenarios. (2) Evaluated stakeholders including electricity consumers, the local community, workers, and society. | This tool could be used to predict how certain interventions would affect different customers and if your intended objectives would be achieved. |

| Cong et al., 2022 [19] Unveiling hidden energy poverty using the energy equity gap | Analyzed residential electricity consumption data and developed a new metric and illustrated “energy limiting behavior”. | The results show that households can limit the energy they would otherwise use to save money. This energy limiting behavior affects energy equity. |

| Article | Methods | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Saunders et al., 2021 [24] Energy Efficiency: What Has Research Delivered in the Last 40 Years? | Assessed the direct and indirect benefits of policies using metrics like: energy technology costs, energy productivity, energy use per unit of economic output, emission reductions, and social benefit. | Energy efficiency gains can spur the development of new energy using technologies and increase disposable income and profitable production output increasing energy demand |

| Raissi et al., 2020 [25] “If we had a little more flexibility”. Perceptions of programmatic challenges and opportunities implementing government funded low-income energy efficiency programs | (1) Conducted interviews with program managers from the DOE Weatherization Assistance Program (2) Evaluation metrics included: percentage of low-income households, implementation procedures, energy and non-energy related benefits, implementation challenges, and opportunities for expansion. | Three funding related challenges (funding instability, funding allocation formula, limited advertising and marketing funding) and two regulatory related challenges (cumbersome paperwork and restrictive guidelines) dramatically affect the efficacy of these programs and keep them from achieving their desired outcomes. |

| Bednar et al., 2020 [2] Recognition of and response to energy poverty in the United States | (1) Critical analytical study of the energy poverty assistance programs in the US. (2) Evaluated based on Department of Health and Human Services LIHEAP annual performance goals, specifically the recipiant targeting index. (3) Measured metrics such as: cost-effective energy savings, health and safety benefits, job creation, reliability, number of retrofits. | The absence of a formal recognition of energy poverty constrains the efficient application of aid. Instead, most aid is delivered based on metrics like income which constrains the ability to address energy poverty and its root causes directly. |

| Article | Methods | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Glasgo et al., 2020 [29] Simulating a residential building stock to support regional efficiency policy | Performed a comparative analysis of the residential sector using building simulations tools and energy audit records of single-family homes in Pennsylvania. Detailed residential characteristics provided by the Public Utilities Commission (PUC) | Showed that the energy efficiency gains can spur the development of new energy using technologies and increase disposable income and profitable production output increasing energy demand. |

| Adekan et al., 2020 [30] Federal policy, local policy, and green building certifications in the U.S. | Performed a qualitative examination of policies that encourage green building certifications specifially LEED across numerous metropolitan statsical areas (MSA) | Local and Federal policy can increase uptake in green building certification. However, Energy consumption information is not available for these buildings making it difficult to measure the real impacts of greening a retrofitted building. |

| Keady et al., 2021 [31] Energy justice gaps in renewable energy transition policy initiatives in Vermont | Used an anti-resilience framework, a perspective that highlights the need to change existing structures of inequality rather than just helping individuals adapt or become resilient within them. | Finds that marginalized groups are more likely to face energy vulnerability as they lack access to sufficient and affordable energy. Furthermore, Non-white and renting respondents were significantly less likely to report having solar panels, suggesting that the benefits of renewable energy policies are not reaching these vulnerable groups. |

| Heleno et al., 2022 [32] Optimizing equity in energy policy interventions: A quantitative decision support framework for energy justice | Used a linear programming model that derives an optimal mix of interventions that minimize energy security. The approach combines sociodemographic and techno-economic models centered on energy security and equity. | Shows that by incorporating different sociodemographic dimensions, equitable policy interventions become heterogeneous, specific to each community, which indicates a need for holistic (place based) implementations. Results should be used to inform decision making as a starting discussion point. |

| Article | Methods | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Heeter et al., 2022 [34] Incorporating energy justice into utility-scale photovoltaic deployment: A policy framework | Evaluates two mechanisms to contribute to restorative justice: (1) Direct Electricity Bill Reduction and (2) procurement of utility-scale PV by entities from PV projects financed, owned, and/or developed by minority-owned businesses. | The findings suggest that while the mechanism of direct electricity bill reduction can provide some relief, it does not necessarily contribute to restorative justice via wealth creation. The paper concludes by proposing specific policy and program recommendations to ensure that the benefits of utility-scale PV systems are properly distributed to underserved communities, thus contributing to a more equitable energy transition. |

| Fonseca et al., 2021 [35] Climate-Induced Tradeoffs in Planning and Operating Costs of a Regional Electricity System | Created a two-stage optimization modeling framework to quantify tradeoffs between climate change mitigation, reliability, and other social metrics. | Shows that planning decisions that do not include climate-induced impacts will increase social costs, including health effects, and increase loss of load incidents. |

| Elmallah et al., 2022 [36] Frontlining energy justice: Visioning principles for energy transitions from community-based organizations in the United States | Reviewed 60 visioning documents from CBOs outlining what energy justice meant to them. | Identified 6 principles of a just energy future: (1) being place-based, (2) addressing the root causes and legacies of inequality, (3) shifting the balance of power in existing forms of energy governance, (4) creating new, cooperative, and participatory systems of energy governance and ownership, (5) adopting a rights-based approach, and (6) rejecting false solutions. |

| Goforth et al., 2022 [37] Air pollution disparities and equality assessments of US national decarbonization strategies | Investigated the distributional equality of air pollution impacts by combining an optimization based capacity expansion model with a reduced complexity air pollution model. | Without any decarbonization policies, the authors find that Black and high poverty communities could face higher PM2.5 concentrations. Nationwide mandates requiring the deployment of renewable or low-carbon technologies to the extent of more than 80% can achieve equal distribution of air pollution across all demographic groups. |

| Janicke et al., 2023 [38] Air pollution co-benefits from strengthening electric transmission and distribution systems | Created a lifecycle assessment and uncertainty analysis to estimate T&D losses contributed global emissions and cost analysis for CO reductions | Shows that investing in T&D infrastructure could be beneficial for reducing air pollution in disadvantaged neighborhoods quickly, even more so that speeding up a fully decarbonized system. |

| Baker et al., 2020 [39] Robust portfolio decision analysis: An application to the energy research and development portfolio problem | Performed a Robust Portfolio Decision Analysis informed by a new dominance concept called “Belief Dominance” | Shows that an energy just portfolio must include: (1) the allocation of research funds across energy technologies; (2) the impact of the performance of a technology in terms of cost and efficiencies |

| Article | Methods | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Ravikumar et al., 2022 [6] Enabling an equitable energy transition through inclusive research | Performed descriptive analysis on the stratgies implemented by the government for an equitable energy transition | Outlined five key action items for government agencies and philanthropic institutions to integrate into their strategies: (1) Reframing Equity; (2) Direct Engagement; (3) Developing Formal Mechanisms; (4) Expanding Review and Award Criteria; (5) Instituting Structural Reforms |

| Reames, 2021 [22] Exploring Residential Rooftop Solar Potential in the United States by Race and Ethnicity | Analyzed the National Renewable Energy Lab’s (NREL) Rooftop Energy Potential of Low-Income Communities in America (REPLICA) dataset to evaluate single family rooftop potential across racial and ethnic majority census tracts | Illustrates that even if the majority of homes in communities of color are suitable to execute solar energy sources, an equitable clean energy transition is only possible with policies targeting racial equity. |

| Spurlock et al., 2022 [40] Equitable deep decarbonization: A framework to facilitate energy justice based multidisciplinary modeling | Created an Equitable Deep Decarbonization Framework to the tenets of energy justice to decarbonization models | Argues that modeling for deep decarbonization needs to enter restorative justice and develops an equitable deep decarbonization framework for those ends. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jones, E.C., Jr.; Reyes, A. Identifying Themes in Energy Poverty Research: Energy Justice Implications for Policy, Programs, and the Clean Energy Transition. Energies 2023, 16, 6698. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16186698

Jones EC Jr., Reyes A. Identifying Themes in Energy Poverty Research: Energy Justice Implications for Policy, Programs, and the Clean Energy Transition. Energies. 2023; 16(18):6698. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16186698

Chicago/Turabian StyleJones, Erick C., Jr., and Ariadna Reyes. 2023. "Identifying Themes in Energy Poverty Research: Energy Justice Implications for Policy, Programs, and the Clean Energy Transition" Energies 16, no. 18: 6698. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16186698

APA StyleJones, E. C., Jr., & Reyes, A. (2023). Identifying Themes in Energy Poverty Research: Energy Justice Implications for Policy, Programs, and the Clean Energy Transition. Energies, 16(18), 6698. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16186698