Abstract

Interest in and acquisition of energy-efficient items and pro-environmental products and the scale of these purchases depend on consumer attitudes, especially those related to beliefs that such products are usually more expensive than their nonenergy-efficient counterparts. However, green skepticism is a phenomenon that weakens the willingness to buy both energy-efficient and pro-environmental products. This skepticism is enhanced by the phenomenon of greenwashing, which has become a popular way of competing, whereby companies strive to appear to be more environmentally friendly than they are. Therefore, we wanted to investigate consumer attitudes toward energy-efficient products and environmentally friendly purchases. We conducted a survey using a computer-assisted web interview (CAWI) technique throughout Poland. The research sample included 1000 individuals and was representative of gender, age, and place of residence. The results of our study showed that women, people with a higher education, and people in better financial situations accept higher prices for products that do not cause environmental damage. Moreover, willingness to pay higher prices for products that do not cause environmental damage correlates negatively with a negative assessment of producers’ social responsibility and with a negative assessment of consumers’ social responsibility. We proposed theoretical and practical implications.

1. Introduction

Most energy is still generated from nonrenewable resources [1]. However, the increasing scale of the possession and use of electrical appliances has made energy efficiency one of Poland’s energy policy priorities. On the one hand, the European Union has developed a directive on energy savings in individual Member States [2]. On the other hand, there is growing interest in both saving energy in households and energy-efficient products. That interest in and acquisition of energy-efficient items and the scale of these purchases depend on consumer attitudes, especially those related to beliefs that such products are usually more expensive than their nonenergy-efficient counterparts. Elements of attitudes favoring the purchase of energy-efficient products are consumers’ personal beliefs and norms [3] and trust in the information provided [4]. Other factors influencing the purchase of energy-efficient products are their quality [5] and potential consumer benefits [6].

In turn, buying environmentally friendly products is a way to minimize the negative impact of consumption on the environment [7]. In the typology of pro-environmental consumer behaviors within product-oriented purchasing, we can distinguish the following: (1) boycotting, e.g., not buying aerosols; (2) sustainable consumerism, e.g., avoiding buying certain products considered to be harmful to the environment; (3) positive buying, e.g., purchasing only energy-efficient products or those marked with a unique label for green products [8,9]. In green consumption, buyers consider the environmental impact of buying, using, and disposing of different products [10]. Green purchasing behavior is affected by consumers’ material status [11], tertiary education [12], and knowledge of the environmental impacts of products [13]. Consumer attitudes toward the environment are equally important [14,15]. Women tend to be more concerned than men that the products they buy positively impact health and protect the environment [16].

However, green skepticism is a phenomenon that weakens the willingness to buy both energy-efficient and pro-environmental products [17]. Some researchers point to cultural and worldview sources of green skepticism. Individualist cultures are characterized by more prevalent green skepticism than collectivist cultures [18,19,20]. Additionally, people with conservative and religious worldviews have been found to be more likely to be skeptical about humans’ ability to influence the global environment [21]. On the other hand, conservatives are often affirmative about the very idea of environmental protection (see, e.g., [22]). Thus, green skepticism is not always rooted in a personal worldview. This skepticism may be enhanced by the phenomenon of greenwashing [23]. Greenwashing has become a popular way of competing, whereby companies strive to appear to be more environmentally friendly than they are [24]. Consumers’ conviction that one company’s products are fraudulent brings about the spread of green skepticism to other products and companies [25]. Consequently, consumers’ faith in the sincerity of the manufacturers’ green approach to the products on offer decreases. High-profile corporate scandals, such as the falsification of emissions results in Volkswagen engines, also do not help [26]. Previous incidents of greenwashing in large-scale companies have stimulated green skepticism [18]. Another cause of green skepticism comes from corporations’ irresponsible environmental behavior, such as allowing the Fukushima nuclear disaster [27]. All of these increase consumer skepticism about companies’ green actions.

It is, therefore, important to investigate the impact of consumer green skepticism on decisions and purchasing habits regarding energy and the environment. Another problem we wanted to address was consumer attitudes toward energy-efficient products and environmentally friendly purchases as a function of gender, education, and financial status. Finally, we also sought answers to whether consumers would be willing to pay more for green products and when they would be willing to pay more for energy-saving products.

Our study makes the following contributions to science. First, we present the results of an examination of determinants of consumer attitudes toward energy-efficient and pro-environmental products, including education, gender, and wealth level, based on a representative national research sample. The research was conducted in Poland, one of a group of countries transitioning from developing to developed countries and whose society is relatively conservative compared to the rest of the EU. These characteristics provide an interesting comparative context. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study discussing the impact of green skepticism on consumer attitudes toward buying energy-efficient products and willingness to pay a higher price for environmentally friendly products in Poland.

2. Literature Review and Development of the Hypotheses

2.1. Willingness to Pay More for Products That Do Not Cause Environmental Damage

The willingness to pay more for products that do not cause environmental damage is the domain of most environmentally conscious consumers [28]. Moreover, they are for the most part better educated and better off than the rest of society [28]. This mostly manifests as buying organic food, and the motives for its consumption can be both ideological and hedonistic [29]. In Spain, for example, a willingness to pay approximately 20% more for organic food has been reported [30]. The following relationship was found in Poland: the older the consumers were, the more they expressed a willingness to buy “green” products at higher prices [31].

Do Paco et al. [32] found that women were more likely than men to buy pro-environmental and energy-efficient goods. In addition, women opted for behaviors directed toward energy conservation [30,33]. In Croatia, women were more ready to buy organic food than men [12]. Irianto [16] described similar differences in attitudes, claiming that women were more concerned about being healthy and buying organic food products than men. Additionally, research in the USA indicates that women are more frequent consumers of organic food products than men (see, e.g., [34]). A review of previous studies also confirms this finding [35]. The results of research conducted in Poland turned out to be similar [36]. In Poland, the primary motivation for green consumption is health [37]. Polish women also display more positive attitudes toward organic products than men [31,38].

The above considerations led us to the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1.

Women are more likely to accept higher prices for products that do not cause environmental damage than men.

One of the barriers to the development of green consumption is insufficient knowledge of the labeling, certification, and control of green products. This affects distrust and skepticism toward calling products green and lack of acceptance of higher product prices [37]. Better-educated consumers showed more positive attitudes toward all environmental aspects and were willing to pay higher prices [32]. They were also more often ready to buy, for example, organic food [12]. This was also confirmed by reviewing previous research by Rödiger and Hamm [35]. Those with higher education chose behaviors directed toward energy conservation [33]. Knowledge of the environmental impact of production, which is usually associated with a higher education, also positively influenced green purchase [13]. However, too much knowledge about the nuances of the environmental impact of using different products can lead to dilemmas and tensions, and even paralysis when considering buying more or less “green” products [39]. Usually, the most informed “green” consumers willing to pay more for environmentally friendly and energy-efficient products were those with the best education [28]. Better-educated people were also more oriented toward pro-environmental products in Poland [40].

Therefore, we formulated the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2.

People with higher education, relative to those with less education, accept higher prices for products that do not cause environmental damage.

Socioeconomic status plays a significant role in buying organic products [11,28]. Wealthier eco-aware consumers were willing to pay higher prices and presented a high degree of criticism of companies’ promotional practices [28,32]. Those with higher material status spent more on organic food [41,42], including organic meat [34]. This was also confirmed by reviewing previous studies [35]. The inflated prices of organic products were, in turn, an obstacle to their widespread sale [35,43]. Studies in Poland have also shown that the higher one’s personal material status, the more likely one is to declare his/her willingness to buy organic products [31,40].

Therefore, we formulated the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3.

People assessing their financial situation as better are more likely to accept higher prices for products that do not cause environmental damage than others.

2.2. Skepticism about the Social Responsibility of Entrepreneurs and Consumers and Willingness to Buy Energy-Efficient Products

Poor knowledge of certification and control rules for green products affects consumer mistrust and skepticism. Under these conditions, consumers are unwilling to accept higher product prices [37]. In addition, Polish culture is individualistic, which further favors green skepticism [18,44].

Consumers’ positive attitudes toward purchasing energy-efficient appliances positively influence their willingness to pay a higher price [45]. Personal beliefs about the environment, together with ethical factors from consumers’ social backgrounds, impact positive attitudes toward buying more environmentally friendly products [46]. Skepticism toward pro-environmental declarations is related to consumers’ reactions to promotional information at the level of advertising, packaging, and labeling [28]. This stems from greenwashing, which can be defined as “selective disclosure of positive information about a company’s environmental or social performance, without full disclosure of negative information on these dimensions, so as to create an overly positive corporate image” ([25], p. 9). Despite corporate greenwashing awareness, it has been shown that environmentally conscious consumers are willing to pay more for energy-efficient products and reduce negative environmental impacts [32]. Greenwashing has a divergent effect on stakeholders depending on whether it occurs at the company or product level [47].

Another factor influencing the acquisition of energy-efficient products, reinforced by a sense of social responsibility, is the potential benefits of the purchase for the consumer [6]. This is especially true for energy-efficient electrical appliances, which are less expensive to use. However, it was found that one’s attitude toward an energy-efficient product related to brand loyalty was more important than its actual energy efficiency [48]. Either way, the motive for energy efficiency, in addition to a pro-environmental attitude, may, in fact, be a simple calculation and the desire to benefit from expenditure savings. This is indicated by the fact that older and professionally less active people save energy more [31]. Furthermore, in a study of the so-called “green” habits in Poland, we found that they are often related to saving water and energy, so some people are driven by economic factors rather than environmental concerns [38].

Therefore, we formulated the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 4.

Willingness to buy energy-efficient products is independent of a negative evaluation of producers’ social responsibility.

Personal values and beliefs influence green purchase [15,49]. Adhering to environmental values influences consumers’ green purchase [45]. Knowledge of the environmental impact of manufacturing also positively influences green purchase [13].

Green skepticism is defined as “consumers’ tendency to doubt the environmental benefits or the environmental performance of a green product” ([17], p. 402). Due to greenwashing, consumers’ trust in the sincerity of producers’ green approach to the products on offer has decreased, and green skepticism has increased [24,50]. Furthermore, greenwashing is negatively related to green purchase intentions, and green skepticism mediates this relationship [51]. Interestingly, greenwashing does not positively affect the finances of companies that use it [52].

Findings show that green skepticism inhibited purchase intentions for environmentally protective products [17]. Green skepticism moderates the relationship between environmental attitudes and green purchase intentions [53]. Albayrak et al. [54] showed that customers who are less skeptical and have a high level of environmental concern have a stronger intention to switch from traditional invoices to e-invoices to prevent natural resource consumption. Skepticism reduces ecological anxiety and harms green purchasing behavior [55]. Goh and Balaji [56] obtained similar results for emerging economies. Under green skepticism, consumers are unwilling to accept higher product prices [37].

Following these considerations, we formulated the next hypothesis.

Hypothesis 5.

Willingness to pay higher prices for products that do not cause environmental damage correlates negatively with a negative assessment of producers’ social responsibility.

Consumers’ social responsibility is defined as “the conscious and deliberate choice to make certain consumption choices based on personal and moral beliefs” ([57], p. 32). Personal values and beliefs influence green consumption, because the consumer feeling socially responsible is more susceptible to the actions of the producer’s corporate social responsibility [15,58]. Consumers with a high level of environmental consciousness pay more attention to the environmental impact of the production of goods considered for purchase [59]. In turn, the factor weakening this relationship is consumer skepticism [59,60] and consumer cynicism [61]. Consumer cynicism is a personality trait or habitual disposition manifested in persistent disbelief and distrust in response to CSR activities [61]. Skepticism and cynicism toward an organization are negatively associated with purchase intention [62]. Skepticism reduces the motivation to engage in the company’s ecological CSR [63]. Consumer social responsibility is the consumer’s response to corporate social responsibility [58]. Greenwashing and disbelief in sincere intentions as to corporate social responsibility lead to cynicism and skepticism also towards consumer social responsibility [64].

Therefore, we formulated the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 6.

Willingness to pay higher prices for products that do not cause environmental damage correlates negatively with a negative assessment of consumers’ social responsibility.

3. Research Methods and Tools

The present survey aimed to identify Poles’ shopping habits and their attitudes toward corporate social responsibility in terms of saving energy and environmental protection. The sample was selected randomly using the ePanel.pl platform. The survey was conducted using a computer-assisted web interview (CAWI) technique. The CAWI method is more effective than others, and 70% of Poles have access to the Internet. The questionnaire was programmed with the use of CADAS software. The sampling procedure was probabilistic. The research sample included 1000 individuals and was representative of gender, age, and place of residence (town size and region). Additionally, information was collected on the education, professional status, and subjective assessment of the respondents’ material situation. The surveyed group of respondents reflected the characteristics of the general population. Due to its representativeness, this would allow generalizing the final conclusions. The described selection of the sample allowed inferring a maximum error of 3% and a confidence level of 95%. The survey, preceded by a pilot study, was conducted in the period from 27 July to 9 August 2021.

3.1. Survey Questionnaire

The proprietary questionnaire was developed at the Management Institute of the Warsaw School of Economics. We present responses to the following statements:

- -

- I am willing to pay a higher price for products that do not cause damage to the environment;

- -

- I try to buy energy-efficient products.

Green skepticism was examined and divided into skepticism about producer social responsibility and skepticism about consumer social responsibility. Skepticism about producers’ social responsibility was examined by analyzing responses to the following two statements:

- -

- - Corporate social responsibility is just a fad;

- -

- - Corporate social responsibility is show-business.

Skepticism about consumer social responsibility was explored by analyzing responses to the following two statements:

- -

- - Consumer social responsibility is an incomprehensible, vague concept;

- -

- - Consumer social responsibility is the shifting of responsibility by companies and governments to ordinary people.

Responses to all statements were given using a Likert scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 4 = difficult to say, 7 = strongly agree.

3.2. Research Group Characteristics

A total of 1000 people participated in the survey, 53% women and 47% men. The respondents’ ages varied. There were 9% were aged 18–24, 16% aged 25–34, 20% aged 35–44, 16% aged 45–54, 18% aged 55–64, and 16% aged 65–80. Respondents originated from different locations. There were 32% who lived in villages and towns with up to 9000 inhabitants, 25% in towns with 10,000–49,000 inhabitants, and 16% in cities with a population of 500,000 plus. The towns the respondents came from were regionally spread evenly across Poland. There were 50% of respondents having a higher education, 40% secondary, and 10% vocational or primary backgrounds. The respondents’ perceived material status was diversified. There were 2% indicating that they lived very modestly, 13% modestly, 60% indicating that “we live moderately,” 23% indicating that “we live well”, and 2% considering themselves to live very well.

4. Results

4.1. Willingness to Pay Higher Costs

Table 1 shows the distribution of the willingness to pay higher prices for products that do not cause environmental harm in the female and male groups.

Table 1.

Acceptance of higher prices for products that do not cause environmental damage in the female and male groups.

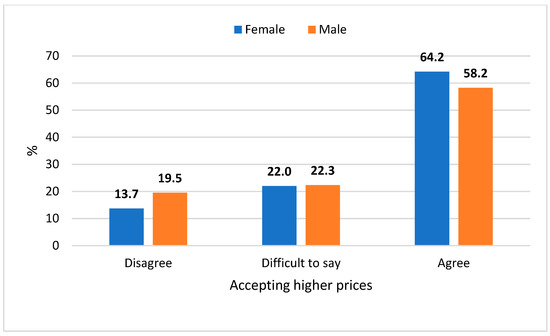

Based on the value of the x2 test, the relationship between respondents’ gender and their willingness to pay higher prices for pro-environmental products was found to be statistically significant, x2(2) = 6.54, p < 0.05. More respondents in the female group accepted higher prices for environmentally friendly products than in the male group (cf. Figure 1). This confirms Hypothesis 1 of our study.

Figure 1.

Percentage frequency distribution of accepting higher prices for products that do not cause environmental damage among women and men.

Table 2 shows the distribution of willingness to pay higher prices for products that do not cause damage to the environment depending on the respondents’ level of education.

Table 2.

Acceptance of higher prices for products that do not cause damage to the environment depending on respondents’ level of education.

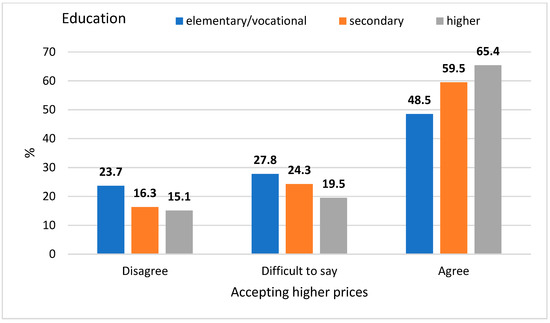

Based on the value of the x2 test, the relationship between respondents’ education level and their willingness to pay higher prices for pro-environmental products was found to be statistically significant, x2(4) = 11.69, p < 0.05. In the group of people with higher education, more people were willing to pay higher costs for products that do not harm the environment (cf. Figure 2). This confirms Hypothesis 2 of our study.

Figure 2.

Percentage frequency distribution of accepting higher prices for products that do not cause environmental harm according to respondents’ education.

Table 3 shows the distribution of willingness to pay higher prices for products that do not cause environmental damage depending on the material situation of the respondents.

Table 3.

Acceptance of higher prices for products that do not cause damage to the environment depending on the perceived economic status of the persons surveyed.

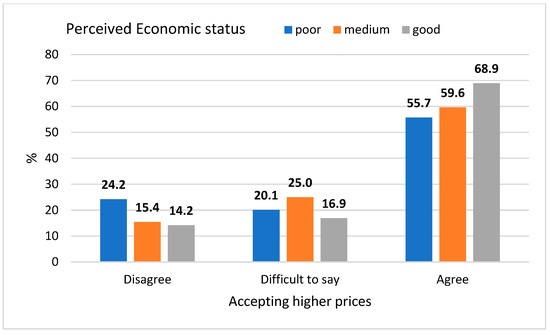

Based on the value of the x2 test, the relationship between the perceived material situation of respondents and their willingness to pay higher prices for pro-environmental products was found to be statistically significant, x2(4) = 15.30, p < 0.01. Individuals enjoying good economic status were more likely to pay higher prices than individuals of poor economic status (cf. Figure 3). This confirms Hypothesis 3 of our study.

Figure 3.

The percentage frequency distribution of accepting higher prices for products that do not cause environmental damage depending on the financial situation of the persons surveyed.

Based on the value of the x2 test, no statistically significant correlation was found between the size of the place of residence of the respondents and the acceptance of higher prices, x2(4) = 3.71, p > 0.05. Based on the value of the x2 test, no statistically significant correlation was found between the voivodship (region) and the acceptance of higher prices, x2(30) = 26.04, p > 0.05.

4.2. Willingness to Pay More and Negative Evaluation of Corporate and Consumer Social Responsibility

Table 4 presents Pearson’s r correlation coefficients between buying energy-efficient products and negative evaluations of corporate and consumer social responsibility.

Table 4.

Correlation coefficients between buying energy-efficient products and negative evaluations of corporate and consumer social responsibility.

The results obtained in response to the “I try to buy energy-efficient products” statement correlated positively with the negative assessment of the social responsibility of entrepreneurs. However, no statistically significant correlation was found with the negative evaluation of consumers’ social responsibility p (n = 1000) = 0.024, p > 0.05.

These results partially confirm Hypothesis 4 of our study. Therefore, the conclusion was that there is no correlation between green skepticism and willingness to buy energy-efficient products, and skepticism about corporate social responsibility correlates with increased willingness to buy energy-efficient products.

Table 5 shows Pearson’s r correlation coefficients between willingness to pay more and negative evaluations of corporate and consumer social responsibility.

Table 5.

Correlation coefficients between willingness to incur higher costs and negative evaluations of corporate and consumer social responsibility.

Statistically significant negative correlations were obtained between willingness to bear higher costs and negative evaluations of corporate social responsibility and consumer social responsibility. This confirms Hypotheses 5 and 6 of our study.

5. Discussion

The results of our study indicate that women are more likely than men to pay more for green products, with a similar percentage of “difficult to say” responses (see Figure 1). In Poland, as elsewhere in the world, women show a higher propensity to buy products with a lower negative environmental impact. This result also corresponds with previous studies [30,36]. Education has a much greater impact on the willingness to buy green products. Respondents with a secondary education are more willing to buy green. On the other hand, respondents with a higher education are significantly more willing to buy green products than respondents with a secondary education (see Figure 2). The perceived economic status influences the willingness to buy green in a significant way. Respondents who perceived themselves as poor are much less likely to accept higher prices of green products than respondents who describe their material status as medium or good (see Figure 3). On the other hand, respondents who assess their material status as good accept higher prices of green products much more often than respondents who describe themselves as medium or poor (see Figure 3). Our findings regarding the second and third hypotheses confirm the results of similar studies carried out in different countries. Better-off and better-educated individuals tend to be more willing to buy products that support environmental protection and are inclined to pay more for such products [11,28,33,40].

There was no correlation between green skepticism and willingness to buy energy-efficient products. In turn, skepticism about corporate social responsibility correlated with increased willingness to buy energy-efficient goods. Many researchers draw attention to a specific group of consumers who are sometimes referred to as “true greens” [38]. In Poland, these people are concerned about environmental issues and show the highest level of knowledge compared to other customer segments. At the same time, they believe that they can contribute to environmental protection. Moreover, they show a willingness to pay a premium for green products and higher taxes to protect the environment [38]. Apart from pragmatic financial reasons, perhaps an interpretation of the results indicating a correlation of increased willingness to buy energy-efficient products with skepticism about responsible business should be sought in the analysis of the behavior of this consumer group.

On the other hand, the conclusions of Hypotheses 5 and 6 were different. Many respondents reduce their commitment to buying products with less negative environmental impact because of their green skepticism. This would indicate a profitability-related interpretation for Hypothesis 4. There is a relationship between environmental beliefs and consumer attitudes towards green products [65]. This influences consumers’ attitudes about the willingness to buy pro-environmental products [66]. Consumers seem unwilling to pay more and sacrifice their own money to protect the environment when corporations cheat in this regard or pass the problem on to consumers.

Our paper, as many others, has some limitations. The first is the questionnaire’s general formulation of the willingness to make energy-efficient purchases. Both energy-efficient electrical appliances and, for example, purchases of clothes produced with energy savings or buying organic food fall into one response category. Future research should separate these two categories.

A second research limitation is an apparent discrepancy between consumers’ declarations and their behavior in the green products market. For example, one can observe the phenomenon of a hypothetical willingness to pay, which means that consumers’ willingness to pay inflated prices is declarative; in reality, they may find it more difficult to accept a higher market premium [29]. More thorough research could make consumer declarations more realistic. Another research limitation is as follows. People living in rural areas have easier access to organic food than city dwellers. Such features may influence their attitude towards green consumption. Another limitation is the fact that the survey was the result of collective creative work and had not been previously validated.

6. Conclusions

An idea for future research could be to conduct experimental studies on the greenwashing effect on green skepticism. Qualitative research on green skepticism could also bring fresh insights to its impact on consumer attitudes.

Our study confirmed previous descriptions of factors influencing environmentally sensitive consumption. We found that in Poland, as in other countries, women are more susceptible to environmental problems than men are. Additionally, respondents’ higher education and assessing their financial standing as better affect green shopping behavior. On the other hand, the green skepticism phenomenon, often resulting from greenwashing at the corporate or product level, significantly reduces involvement in green consumption. In the case of energy-efficient products, this is partly mitigated by the cost-effectiveness of purchasing energy-efficient electrical appliances, hence the significance of labeling and marking in this respect. A practical conclusion from the research is the need for continued investment in reliable information on products’ environmental impact. Perhaps there is also a demand for more specific regulations to hinder greenwashing, which, through consumers’ green skepticism, reduces willingness to make green purchases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K.-G. and T.G.; methodology, K.K.-G. and T.G.; software, T.G.; validation, K.K.-G. and T.G.; formal analysis, K.K.-G. and T.G.; investigation, K.K.-G. and T.G.; resources, K.K.-G. and T.G.; data curation, K.K.-G. and T.G.; writing—original draft preparation, T.G.; writing—review and editing, K.K.-G.; visualization, K.K.-G. and T.G.; supervision, K.K.-G.; project administration, K.K.-G.; funding acquisition, K.K.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to the research was conducted using the technique of internet interviews (CAWI research), which ensured complete anonymity for the respondents.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhao, S.; Song, Q.; Wang, C. Characterizing the energy-saving behaviors, attitudes and awareness of university students in Macau. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zangheri, P.; Economidou, M.; Labanca, N. Progress in the implementation of the EU energy efficiency directive through the lens of the national annual reports. Energies 2019, 12, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, Q.; Wang, B.; Zhang, B. Purchasing intentions of Chinese consumers on energy-efficient appliances: Is the energy efficiency label effective? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 238, 117896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Cosic, A.; Iraldo, F. Determining factors of curtailment and purchasing energy related behaviours. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 3810–3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.-Y.; Yu, B.; Wang, J.-W.; Wei, Y.-M. Impact factors of household energy-saving behavior: An empirical study of Shandong Province in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Kwon, S.J. What motivations drive sustainable energy-saving behavior? An examination in South Korea. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Mandravickaitė, J.; Bernatonienė, J. Theory of planned behavior approach to understand the green purchasing behavior in the EU: A cross-cultural study. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 125, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, W.; Hwang, K.; McDonald, S.; Oates, C.J. Sustainable consumption: Green consumer behaviour when purchasing products. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.; Newholm, T.; Shaw, D. The Ethical Consumer; Sage: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Moisander, J. Motivational complexity of green consumerism. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, Á.M.; Borchardt, M.; Vaccaro, G.L.R.; Pereira, G.M.; Almeida, F. Motivations for promoting the consumption of green products in an emerging country: Exploring attitudes of Brazilian consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radman, M. Consumer consumption and perception of organic products in Croatia. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchanapibul, M.; Lacka, E.; Wang, X.; Chan, H.K. An empirical investigation of green purchase behaviour among the young generation. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Pretner, G.; Iovino, R.; Bianchi, G.; Tessitore, S.; Iraldo, F. Drivers to green consumption: A systematic review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 4826–4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of consumers’ green purchase behavior in a developing nation: Applying and extending the theory of planned behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irianto, H. Consumers’ attitude and intention towards organic food purchase: An extension of theory of planned behavior in gender perspective. Int. J. Manag. Econ. Soc. Sci. 2015, 4, 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Leonidou, C.N.; Skarmeas, D. Gray shades of green: Causes and consequences of green skepticism. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 144, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, Y.; Wicaksono, H. Advancing on the analysis of causes and consequences of green skepticism. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 320, 128927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreen, N.; Purbey, S.; Sadarangani, P. Impact of culture, behavior and gender on green purchase intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Lobo, A.; Greenland, S. The influence of cultural values on green purchase behaviour. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2017, 35, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalamas, M.; Cleveland, M.; Laroche, M. Pro-environmental behaviors for thee but not for me: Green giants, green Gods, and external environmental locus of control. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scruton, R. Green Philosophy: How to Think Seriously about the Planet; Atlantic Books Ltd.: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Laufer, W.S. Social accountability and corporate greenwashing. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 43, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-H. Greenwash and green trust: The mediation effects of green consumer confusion and green perceived risk. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Maxwell, J.W. Greenwash: Corporate environmental disclosure under threat of audit. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2011, 20, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siano, A.; Vollero, A.; Conte, F.; Amabile, S. “More than words”: Expanding the taxonomy of greenwashing after the Volkswagen scandal. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 71, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, A.J.; Veil, S.R.; Iannarino, N.T. Contaminated communication: TEPCO and organizational renewal at the Fukushima daiichi nuclear power plant. Commun. Stud. 2015, 66, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Paço, A.M.F.; Raposo, M.L.B. Green consumer market segmentation: Empirical findings from Portugal. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2010, 34, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aertsens, J.; Verbeke, W.; Mondelaers, K.; Van Huylenbroeck, G. Personal determinants of organic food consumption: A review. Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 1140–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ureña, F.; Bernabéu, R.; Olmeda, M. Women, men and organic food: Differences in their attitudes and willingness to pay. A Spanish case study. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witek, L.; Kuźniar, W. Green purchase behavior: The effectiveness of sociodemographic variables for explaining green purchases in emerging market. Sustainability 2021, 13, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Paço, A.M.F.; Raposo, M.L.B.; Filho, W.L. Identifying the green consumer: A segmentation study. J. Target. Meas. Anal. Mark. 2009, 17, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, X.; Cheng, H.; Zhao, H.; Jiang, L.; Xue, B. Survey on the households’ energy-saving behaviors and influencing factors in the rural loess hilly region of China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 230, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loo, E.J.; Caputo, V.; Nayga, R.M.; Meullenet, J.-F.; Ricke, S.C. Consumers’ willingness to pay for organic chicken breast: Evidence from choice experiment. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rödiger, M.; Hamm, U. How are organic food prices affecting consumer behaviour? A review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 43, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieżel, M.; Piotrowski, P.; Wiechoczek, J. Pro-ecological behaviours of polish consumers. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Research in Business, Management and Economics, Vienna, Austria, 3–5 December 2019; Diamond Scientific Publishing: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2019; pp. 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Witek, L. Barriers to green products purchase–from polish consumer perspective. In Innovation Management, Entrepreneurship and Sustainability (IMES 2017); Vysoká Škola Ekonomická v Praze: Prague, Czech Republic, 2017; pp. 1119–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Apaydin, F.; Szczepaniak, M. Analyzing the profile and purchase intentions of green consumers in Poland. Ekonomika 2017, 96, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Longo, C.; Shankar, A.; Nuttall, P. “It’s not easy living a sustainable lifestyle”: How greater knowledge leads to dilemmas, tensions and paralysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 759–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witek, L. Idea konsumpcji ekologicznej wśród kobiet. Stud. Ekon. 2017, 337, 194–203. [Google Scholar]

- Bellows, A.C.; Onyango, B.; Diamond, A.; Hallman, W.K. Understanding consumer interest in organics: Production values vs. purchasing behavior. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2008, 6, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriwy, P.; Mecking, R.-A. Health and environmental consciousness, costs of behaviour and the purchase of organic food. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafie, F.A.; Rennie, D. Consumer perceptions towards organic food. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 49, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bartosik-Purgat, M.; Schroeder, J. Polskie społeczeństwo w świetle “wymiarów kulturowych” europejskiego rynku. Acta Univ. Lawodsis Folia Oecon. 2007, 209, 205–221. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, C.; Zhou, G. Willingness to pay a price premium for energy-saving appliances: Role of perceived value and energy efficiency labeling. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, K.; Kinley, T. Green spirit: Consumer empathies for green apparel. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torelli, R.; Balluchi, F.; Lazzini, A. Greenwashing and environmental communication: Effects on stakeholders’ perceptions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ha, H.Y.; Janda, S. Predicting consumer intentions to purchase energy-efficient products. J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-C.; Hung, C.-W. Elucidating the factors influencing the acceptance of green products: An extension of theory of planned behavior. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 112, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aji, H.M.; Sutikno, B. The extended consequence of greenwashing: Perceived consumer skepticism. Int. J. Bus. Inf. 2015, 10, 433. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.T.H.; Yang, Z.; Nguyen, N.; Johnson, L.W.; Cao, T.K. Greenwash and green purchase intention: The mediating role of green skepticism. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Testa, F.; Miroshnychenko, I.; Barontini, R.; Frey, M. Does it pay to be a greenwasher or a brownwasher. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 1104–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, A.; Maleki, F. From decision to run: The moderating role of green skepticism. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2018, 24, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, T.; Aksoy, Ş.; Caber, M. The effect of environmental concern and scepticism on green purchase behaviour. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2013, 31, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, T.; Caber, M.; Moutinho, L.; Herstein, R. The influence of skepticism on green purchase behavior. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2, 189–197. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, S.K.; Balaji, M.S. Linking green skepticism to green purchase behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 131, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devinney, T.M.; Auger, P.; Eckhardt, G.; Birtchnell, T. The Other CSR: Consumer Social Responsibility. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2006, 4, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitell, S.J. A case for consumer social responsibility (CnSR): Including a selected review of consumer ethics/social responsibility research. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangsa, A.B.; Schlegelmilch, B.B. Linking sustainable product attributes and consumer decision-making: Insights from a systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.; Campbell, B.; Hall, C.; Behe, B.; Dennis, J.; Khachatryan, H. Consumer preference for sustainable attributes in plants: Evidence for experimental auctions. Agribus. Int. J. 2016, 32, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W. Toward a Theory of Ethical Consumer Intention Formation: Re-Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. AMS Rev. 2019, 10, 260–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.; Rim, H. The Role of Public Skepticism and Distrust in the Process of CSR Communication. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2019, 232948841986688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, M.-G.; Kim, Y. Megaphoning Effects of Skepticism, Cynicism, and Situational Motivation on an Environmental CSR Activity. Public Relat. Rev. 2021, 47, 102082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Zhang, Q. Green Purchase Intention: Effects of Electronic Service Quality and Customer Green Psychology. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 122053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Sadiq, M.; Talwar, S.; Sakashita, M.; Kaur, P. Why Do Retail Consumers Buy Green Apparel? A Knowledge-Attitude-Behaviour-Context Perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaremohzzabieh, Z.; Ismail, N.; Ahrari, S.; Abu Samah, A. The Effects of Consumer Attitude on Green Purchase Intention: A Meta-Analytic Path Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 732–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).