Evolution of Energy Companies’ Non-Financial Disclosures: A Model of Non-Financial Reports in the Energy Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Standardization and Low Regulation of Non-Financial Reports

- a brief description of the entity’s business model;

- key non-financial performance indicators related to the entity’s operations;

- a description of the entity’s social, labor, environmental, human rights, and anti-corruption policies, and an overview of their results in practice;

- a description of due diligence procedures (if any);

- a description of material risks associated with the entity’s operations that may adversely affect its business, e.g., issues related to the organization’s products or its relationships with the external environment, including counterparties, as well as a description of how such risks are managed.

3. Literature Review

4. Research Methodology and Data

4.1. Sample Selection

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Data Analysis

4.4. Data Description

- (1)

- all reports for the years 2011–2014 were prepared in accordance with GRI 3.1, and those published for 2015 and later were prepared in accordance with GRI 4;

- (2)

- non-financial information is presented on 3937 pages (65%), whereas the remaining pages contain financial information.

5. Empirical Research Results

5.1. Analysis of Stakeholder Relations, Declaration of Ethics, and External Verification of the Report

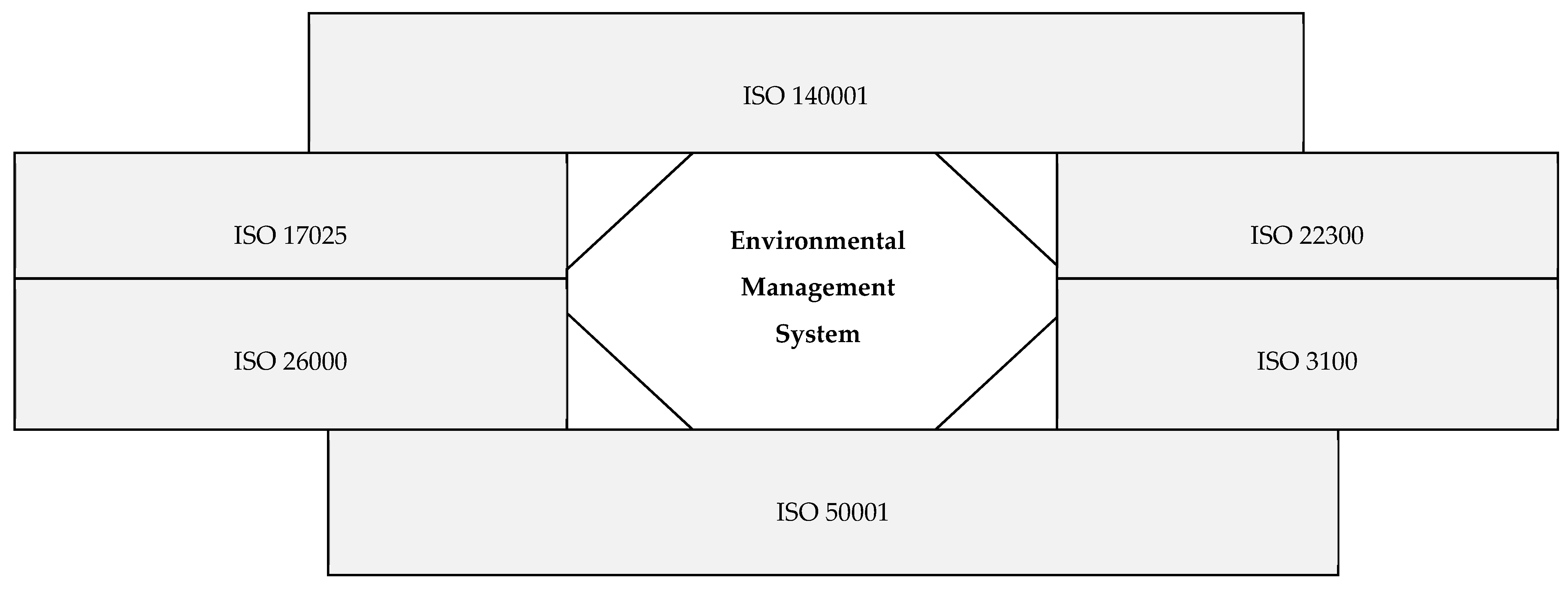

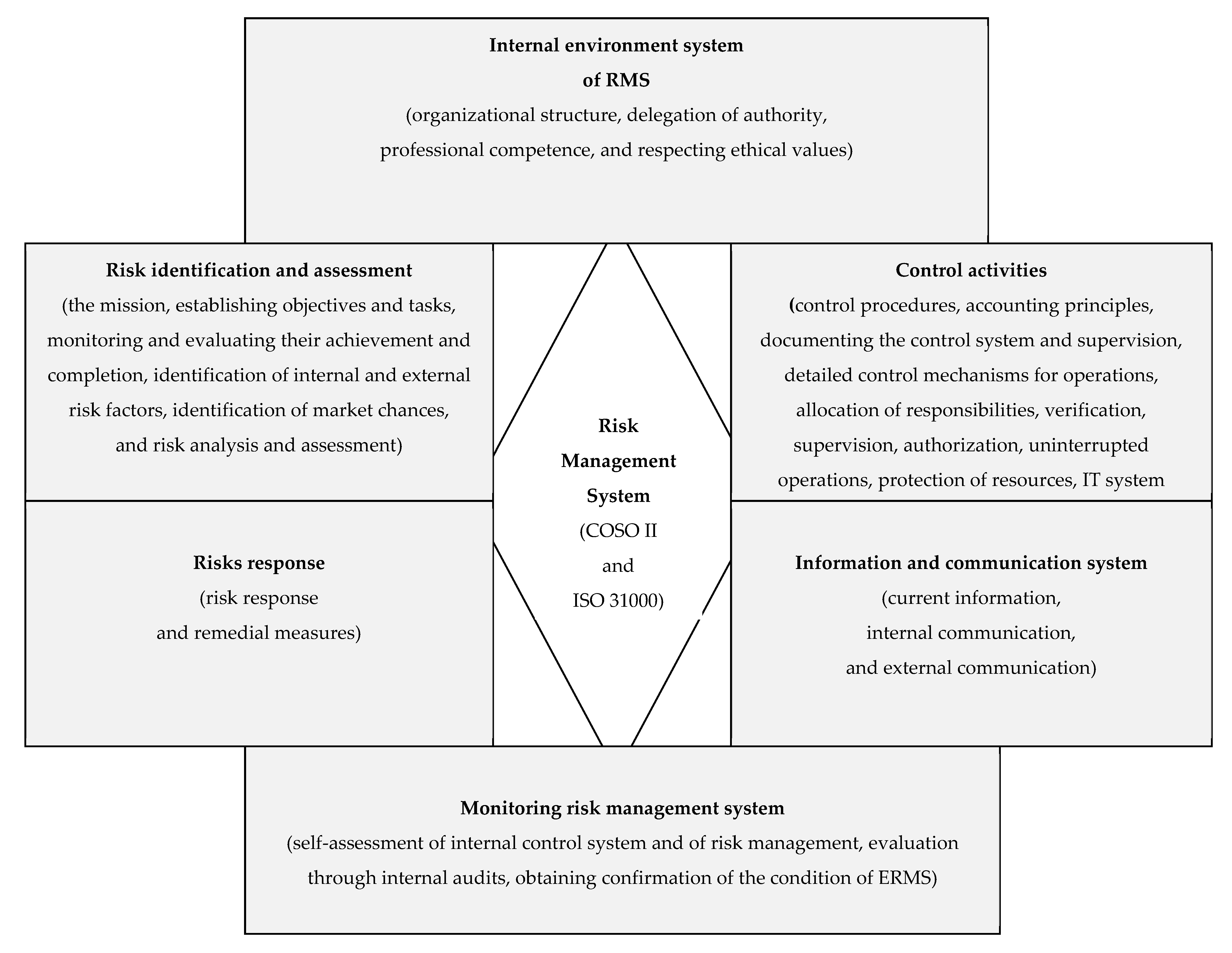

5.2. Analyses of Environmental Management System, Quality Management System, Enterprise Risk Management System, and Corporate Governance Principles

- ISO 17025—General requirements for the competence of testing and calibration laboratories is the main ISO standard used by testing and calibration laboratories;

- ISO 22300 is an international standard developed by ISO/TC 292 Security and resilience. This document defines terms used in security and resilience standards;

- ISO 26000 was last reviewed and confirmed in 2021. It is intended to assist organizations in contributing to sustainable development;

- ISO 31000 is a standard relating to risk management. It provides principles and generic guidelines on managing risks faced by organizations;

- ISO 50001 provides a practical way to improve energy use, through the development of an energy management system (EnMS).

- ISO 9001 is defined as the international standard that specifies requirements for a quality management system (QMS);

- ISO 18001 is one of the International Standard for Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems;

- ISO 27001 is the international standard for information security. It sets out the specification for an information security management system (ISMS);

- ISO 31000 is a standard relating to risk management. It provides principles and generic guidelines on managing risks faced by organizations;

- ISO 37001 concerns anti-bribery management systems. This standard sets out the requirements for the improvement of an anti-bribery management system (ABMS);

- ISO 45001 is a standard for management systems of occupational health and safety (OH&S), which was published in March 2018.

5.3. Assessment of the Quality of Information on Environmental Management Systems, Quality Management Systems, Enterprise Risk Management Systems, and Corporate Governance Principles

- 1—definitely not;

- 2—not;

- 3—difficult to say;

- 4—yes;

- 5—definitely yes.

6. Conclusions and Prospects for Future Research Directions

- The EMS system, emphasizing the need to include the following standards used in the energy sector—ISO 14001, ISO 22300, ISO 31000, ISO 50001, ISO 17025, ISO 26000;

- The QMS system, recommending the description of standards used in the energy sector, such as ISO 9001, ISO 27001, ISO 45000, ISO 18001, ISO 31000 and other ISO standards applicable to Quality Management Systems;

- The ERMS system, taking into account the guidelines on the internal environment system of ERMS, control activities, the information and communication system, risk response and risk identification and assessment;

- The CG system, indicating the need to include in the description of this issue areas such as (1) the skills and experience of the management board and supervisory board members, (2) the remuneration policy and incentive programs, (3) shareholder relations, (4) the avoidance of conflicts of interest by the management board and supervisory board, (5) internal systems and functions, as well as (6) disclosure policy and investor communications.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Directive 2014/95/EU. 2014. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32014L0095 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- European Commision. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/industry/sustainability/corporate-social-responsibility_pl (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- O’Dwyer, B.; Owen, D.; Unerman, J. Seeking legitimacy for new assurance forms: The case of assurance on sustainability reporting. Account. Organ. Soc. 2011, 36, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federation of European Accountants. EU Directive on Disclosure of Non-Financial and Diversity Information the Role of Practitioners in Providing Assurance. Audit & Assurance. 2015. Available online: https://www.accountancyeurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/1512_EU_Directive_on_NFI.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- KPMG. The Road Ahead. The KPMG Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting 2017. 2017. Available online: https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2017/10/kpmg-survey-of-corporateresponsibility-reporting-2017.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Artienwicz, N.; Bartoszewicz, A.; Cygańska, M.; Wójtowicz, P. Kształtowanie Wyniku Finansowego w Polsce: Teoria-Praktyka-Stan Badan; Wydawnictwo IUS Publicum: Kraków, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Beretta, V.; Demartini, M.C.; Lico, L.; Trucco, S.A. Tone Analysis of the Non-Financial Disclosure in the Automotive Industry. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacka, E. Raportowanie danych w obszarach środowiskowym i społecznym w publicznych spółkach sektora energetycznego. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2014, 329, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kowal, B.; Kustra, A. Sustainability reporting in the energy sector. E3S Web Conf. 2016, 10, 00129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąk, S. Realizacja koncepcji społecznej odpowiedzialności w polskich przedsiębiorstwach energetycznych. In Współczesne Problemy Ekonomii–Między Teorią a Praktyką Gospodarczą w Aspekcie Różnorodności; Romanowska, M., Ed.; Polskie Towarzystwo Ekonomiczne: Częstochowa, Poland, 2017; pp. 130–142. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Energii. Krajowy Plan na rzecz Energii i Klimatu na lata 2021–2030 Założenia i cele oraz Polityki i Działania. 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/aktywa-panstwowe/krajowy-plan-na-rzecz-energii-i-klimatu-na-lata-2021-2030-przekazany-do-ke (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Ogrodnik, P. Standardy stosowane w raportowaniu niefinansowym przez polskie spółki z sektora odzież i obuwie, notowane na rynku podstawowym Giełdy Papierów Wartościowych w Warszawie. Stud. I Pr. Kol. Zarządzania I Finans. 2019, 173, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Act of 29 September 1994 on Accounting (Journal of Laws of 2021, Item 217, 2105, 2106). Available online: https://www.global-regulation.com/translation/poland/2985938/act-of-29-september-1994-on-accounting.html (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Pachucki, M.; Plutecki, A. Jak Prawidłowo Wypełniać Obowiązki Informacyjne; Poradnik dla emitentów; Komisja Nadzoru Finansowego: Warsaw, Poland, 2018.

- Bartoszewicz, A.; Rutkowska-Ziarko, A.D. Practice of Non-Financial Reports Assurance Services in the Polish Audit Market-The Range, Limits and Prospects for the Future. Risks 2021, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Act of 11 May 2017 on Statutory Auditors, Audit Firms, and Public Supervision (Journal of Laws of 2017, Item 1089). Available online: https://www.pibr.org.pl/assets/file/2481,Ustawa_uobr_11.05.2017_EN.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Lament, M. Standardy raportowania niefinansowego w podmiotach społecznie odpowiedzialnych w Polsce. Mark. I Rynek. 2017, 11, 298–310. [Google Scholar]

- Piłacik, J. Raportowanie wskaźników środowiskowych według wytycznych Global Reporting Initiative na przykładzie polskich spółek branży energetycznej. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2017, 470, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkos, G.; Nomikos, S. Corporate social responsibility: Trends in global reporting initiative standards. Econ. Anal. Policy 2021, 69, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernacki, P. Wyzwania raportowania niefinansowego. In Raportowanie Niefinansowe. Wartość dla Spółek i Inwestorów; Sroka, R., Ed.; Stowarzyszenie Emitentów Giełdowych GES oraz EY: Warsaw, Poland, 2017; pp. 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Rasche, A. Toward a model to compare and analyse accountability standards—The case of the UN Global Compact. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2009, 16, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado-Lorenzo, J.M.; Gallego-Alvarez, I.; Garcia-Sanchez, I. Stakeholder engagement and Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting: The ownership structure effect. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2009, 16, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Reporting Initiative. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Michalczuk, G.; Konarzewska, U. Standarization of Corporate Social Responsibility reporting using the GRI framework. Optimum. Econ. Stud. 2020, 1, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brown, H.S.; De Jong, M.; Lessidrenska, T. The rise of the Global Reporting Initiative: A case of institutional entrepreneurship. Environ. Politics 2019, 18, 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaja-Cieszyńska, H. Standardy GRI–kierunek dla raportowania na rzecz zrównoważonego rozwoju w organizacjach pozarządowych w Polsce. Stud. I Pr. Kol. Zarządzania I Finans. SGH 2018, 164, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, B.; Owen, D.L. Assurance statement practice in environmental, social and sustainability reporting: A critical evaluation. Br. Account. Rev. 2005, 37, 205–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Różańska, E. Integracja standardów raportowania społecznej odpowiedzialności przedsiębiorstw. Stud. Oeconomica Posnaniensia 2015, 3, 167–177. [Google Scholar]

- Brammer, S.; Pavelin, S. Factors influencing the quality of corporate environmental disclosure. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2008, 17, 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latapí, M.; Jóhannsdóttir, L.; Davíðsdóttir, B. The energy company of the future: Drivers and characteristics for a responsible business framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 288, 125634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pätäri, S.; Arminen, H.; Tuppura, A.; Jantunen, A. Competitive and responsible? The relationship between corporate social and financial performance in the energy sector. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 37, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Karaman, A.S.; Kilic, M.; Uyar, A. Boardattributes, CSR engagement, andcorporateperformance: What is the nexus in the energy sector? Energy Policy 2020, 143, 111582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinescu, D.; Caraiania, C.; Lungua CIMititeana, P. Environmental, social and governance disclosure associated with the firm value. Evidence from energy industry. Account. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2021, 20, 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Karaman, A.S.; Orazalim, N.; Uyar, A.; Shahbaz, M. CSR achievement, reporting, and assurance in the energy sector: Does economic development matter? Energy Policy 2021, 149, 112007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaudacz-Alessandri, M.; Cygańska, M. Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance among Energy Sector Companies. Energies 2021, 14, 6068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowska-Ziarko, A.; Markowski, L. Accounting and Market Risk Measures of Polish Energy Companies. Energies 2022, 15, 2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo, M.A.L.; Johannsdottir, L.; Davidsdottir, B. Drivers that motivate energy companies to be responsible. A systematic literature review of Corporate Social Responsibility in the energy sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 247, 119094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urząd Regulacji Energetyki. Available online: https://www.ure.gov.pl/pl/urzad/informacje-ogolne/aktualnosci/3218,Spoleczna-odpowiedzialnosc-przedsiebiorstw-energetycznych.html (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Figaszewska, I.; Dobroczyńska, A.; Dębek, A. Społeczna Odpowiedzialność Przedsiębiorstw w świetle Badań Ankietowych; Raport; Urząd Regulacji Energetyki: Warsaw, Poland, 2009.

- Szczepankiewicz, E.I.; Mućko, P. CSR Reporting Practices of Polish Energy and Mining Companies. Sustainability 2016, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferens, A. Informacje niefinansowe w sprawozdawczości spółek branży energetycznej. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2019, 63, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szadziewska, A.; Spigarska, E.; Majerowska, E. The disclosure of non-financial information by stock-exchange-listed companies in Poland, in the light of the changes introduced by the Directive 2014/95/EU. Zesz. Teor. Rachun. 2018, 99, 65–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamerschlag, R.; Möller, K.; Verbeeten, F. Determinants of voluntary CSR disclosure: Empirical evidence from Germany. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2010, 5, 233–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raporty Zrównoważonego Rozwoju. Available online: http://raportyzr.pl/informacje-o-konkursie/ (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Striukova, L.; Unerman, J.; Guthrie, J. Corporate reporting of intellectual capital: Evidence from UK companies. Br. Account. Rev. 2008, 40, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unerman, J. Methodological issues-Reflections on quantification in corporate social reporting content analysis. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2000, 13, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- G4 Sustainability Reporting Guidelines. 2013. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/information/g4/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Mućko, P. Jakość sprawozdań narracyjnych i jej determinanty–przegląd literatury. Stud. I Pr. Kol. Zarządzania I Finans. 2018, 165, 155–170. Available online: https://ssl-kolegia.sgh.waw.pl/pl/KZiF/czasopisma/zeszyty_naukowe_studia_i_prace_kzif/Documents/09_Mucko_165.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- Szczepankiewicz, E.I. Identification of Going-Concern Risks in CSR and Integrated Reports of Polish Companies from the Construction and Property Development Sector. Risks 2021, 9, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepankiewicz, E.I.; Błażyńska, J.; Zaleska, B. Comply or Explain Principle in the Context of Corporate Governance in Companies Listed at the Warsaw Stock Exchange. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2021, 24, 281–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepankiewicz, E.I.; Loopesko, W.E.; Ullah, F. A Model of Risk Information Disclosures in Non-Financial Corporate Reports of Socially Responsible Energy Companies in Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepankiewicz, E.I. Selected issues in effective implementation of the integrated risk management system in an organization. Finans. Rynk. Finans. Ubezpieczenia 2011, 49, 153–162. Available online: https://wneiz.pl/nauka_wneiz/frfu/49-2011/FRFU-49-153.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2022).

- Błażyńska, J. Non-financial reporting pursuant to the SIN standard at the WSE. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu u 2020, 64, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WSE. Best Practice for GPW Listed Companies, Dobre Praktyki Spółek Notowanych na GPW 2021; Giełda Papierów Wartościowych (WSE): Warszawa, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sydserff, R.; Weetman, P. A Texture Index for Evaluating Accounting Narratives: An Alternative to Readability Formulas. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1999, 12, 459–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Edition | Number of Entrants from the Energy Sector | Company Name | Number of Editions Attended by the Company | Was the Company’s Report Awarded/Mentioned in the Open Category? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 1 | RWE Polska | 1 | - |

| 2012 | 4 | ENEA S.A. | 1 | - |

| Energa Group | 1 | - | ||

| Fortum Power and Heat Polska | 1 | - | ||

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 1 | - | ||

| 2013 | 2 | RWE Polska | 2 | - |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2 | Yes | ||

| 2014 | 5 | ENEA S.A. | 2 | - |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. * | 3 | Yes | ||

| RWE Polska | 3 | - | ||

| Energa Group | 2 | Yes | ||

| EDF Polska | 1 | - | ||

| 2015 | 6 | EDF Polska | 2 | - |

| Energa Group | 3 | - | ||

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. * | 4 | - | ||

| ENEA S.A. | 3 | - | ||

| RWE Polska | 4 | - | ||

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 1 | - | ||

| 2016 | 5 | ENEA S.A. | 4 | - |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. * | 5 | - | ||

| Energa Group | 4 | - | ||

| EDF Polska | 3 | - | ||

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2 | - | ||

| 2017 | 5 | Energa Group | 5 | - |

| GPEC Group | 1 | - | ||

| ENEA S.A. | 5 | - | ||

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. * | 6 | - | ||

| Polenergia S.A. | 1 | - | ||

| 2018 | 6 | Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 7 | - |

| Energa Group | 6 | - | ||

| ENEA S.A. | 6 | - | ||

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 3 | - | ||

| Veolia Energia Polska | 1 | - | ||

| ZPUE Spółka Akcyjna | 1 | - | ||

| 2019 | 3 | ENEA S.A. | 7 | - |

| Energa Group | 7 | Yes | ||

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 4 | - | ||

| 2020 | 5 | ENEA S.A. | 8 | - |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 8 | Yes | ||

| Energa Group | 8 | - | ||

| Veolia Energia Polska | 2 | - | ||

| Polenergia S.A. | 2 | - | ||

| 2021 | 4 | ENEA S.A. | 9 | - |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 9 | - | ||

| Polenergia S.A. | 3 | - | ||

| PKP Energetyka | 1 | - |

| Company Name | Report for Year | Type of Report | Volume (Pages) | Percent of Pages with Non-Financial Data | GRI Standard |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fortum Power and Heat Polska | 2011 | CSRR | 84 | 94 | GRI 3.1 |

| RWE Polska | 2010 | CSRR | 50 | 96 | GRI 3.1 |

| RWE Polska | 2012 | CSRR | 107 | 98 | GRI 3.1 |

| RWE Polska | 2013 | CSRR | 60 | 98 | GRI 3.1 |

| RWE Polska | 2014 | CSRR | 33 | 97 | GRI 3.1 |

| EDF Polska | 2013 | CSRR | 78 | 100 | GRI 3.1 |

| EDF Polska | 2014 | CSRR | 78 | 100 | GRI 3.1 |

| EDF Polska | 2015 | CSRR | 90 | 99 | GRI 4.0 |

| ZPUE Spółka akcyjna | 2017 | CSRR | 112 | 100 | GRI 4.0 |

| GPEC Group | 2016 | IR | 43 | 23 | GRI 4.0 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2011 | CSRR | 51 | 84 | GRI 3.1 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2012 | CSRR | 104 | 98 | GRI 3.1 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2016–2017 | IR | 316 | 76 | GRI 4.0 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2018–2019 | IR | 518 | 74 | GRI 4.0 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A | 2020 | IR | 523 | 78 | GRI 4.0 |

| Polenergia S.A. | 2016 | CSRR | 72 | 99 | GRI 4.0 |

| Polenergia S.A. | 2019 | CSRR | 136 | 99 | GRI 4.0 |

| Polenergia S.A. | 2020 | IR | 154 | 99 | GRI 4.0 |

| PKP Energetyka | 2020 | CSRR | 100 | 100 | GRI 4.0 |

| Veolia Energia Polska | 2017 | CSRR | 56 | 100 | GRI 4.0 |

| Veolia Energia Polska | 2019 | CSRR | 54 | 98 | GRI 4.0 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2011 | CSRR | 93 | 99 | GRI 3.1 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2013 | CSRR | 81 | 99 | GRI 3.1 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2014 | CSRR | 60 | 100 | GRI 3.1 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2015 | CSRR | 82 | 100 | GRI 4.0 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2016 | CSRR | 116 | 100 | GRI 4.0 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2017 | CSRR | 117 | 100 | GRI 4.0 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2018 | CSRR | 105 | 100 | GRI 4.0 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2019 | CSRR | 123 | 100 | GRI 4.0 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2020 | IR | 235 | 76 | GRI 4.0 |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2013–2014 | CSRR | 114 | 96 | GRI 3.1 |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2015 | IR | 154 | 88 | GRI 4.0 |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2017 | IR | 167 | 88 | GRI 4.0 |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2018 | IR | 187 | 89 | GRI 4.0 |

| Energa Group | 2011 | CSRR | 115 | 98 | GRI 3.1 |

| Energa Group | 2013 | CSRR | 229 | 99 | GRI 3.1 |

| Energa Group | 2014 | CSRR | 139 | 100 | GRI 3.1 |

| Energa Group | 2015 | CSRR | 176 | 99 | GRI 4.0 |

| Energa Group | 2016 | CSRR | 180 | 99 | GRI 4.0 |

| Energa Group | 2017 | CSRR | 221 | 99 | GRI 4.0 |

| Energa Group | 2018 | CSRR | 263 | 99 | GRI 4.0 |

| Energa Group | 2019 | CSRR | 281 | 99 | GRI 4.0 |

| Company Name | Report for Year | Number of Stakeholder Categories | Declaration of Ethics | External Verification of the Report |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fortum Power and Heat Polska | 2011 | 6 | None | No |

| RWE Polska | 2010 | 6 | Code of Ethics | No |

| RWE Polska | 2012 | 10 | Code of Ethics | No |

| RWE Polska | 2013 | 10 | Code of Ethics | No |

| RWE Polska | 2014 | 12 | Code of Ethics | No |

| EDF Polska | 2013 | No data | Code of Ethics | No |

| EDF Polska | 2014 | No data | Code of Ethics | No |

| EDF Polska | 2015 | 7 | Code of Ethics | No |

| ZPUE Spółka akcyjna | 2017 | 8 | Code of Ethics | No |

| GPEC Group | 2016 | No data | None | No |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2011 | 3 | None | Full verification |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2012 | 4 | Code of Ethics | Full verification |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2016–2017 | 10 | Code of Ethics | Full verification |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2018–2019 | 10 | Code of Ethics | Full verification |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A | 2020 | 14 | Code of Ethics | Full verification |

| Polenergia S.A. | 2016 | 10 | Code of Ethics | No |

| Polenergia S.A. | 2019 | 14 | Code of Ethics | No |

| Polenergia S.A. | 2020 | 9 | Code of Ethics | No |

| PKP Energetyka | 2020 | 19 | Code of Ethics | Full verification |

| Veolia Energia Polska | 2017 | No data | Code of Ethics | No |

| Veolia Energia Polska | 2019 | 4 | Code of Ethics | No |

| ENEA S.A. | 2011 | 15 | None | No |

| ENEA S.A. | 2013 | 18 | Code of Ethics | No |

| ENEA S.A. | 2014 | 18 | Code of Ethics | No |

| ENEA S.A. | 2015 | 18 | Code of Ethics | No |

| ENEA S.A. | 2016 | 18 | Code of Ethics | No |

| ENEA S.A. | 2017 | 18 | Code of Ethics | No |

| ENEA S.A. | 2018 | 18 | Code of Ethics | No |

| ENEA S.A. | 2019 | 18 | Code of Ethics | No |

| ENEA S.A. | 2020 | 18 | Code of Ethics | Full verification |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2013–2014 | 14 | Code of Ethics | No |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2015 | 14 | Code of Ethics | Full verification |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2017 | 14 | Code of Ethics | Full verification |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2018 | 14 | Code of Ethics | Full verification |

| Energa Group | 2011 | 13 | Code of Ethics | No |

| Energa Group | 2013 | 16 | Code of Ethics | Full verification |

| Energa Group | 2014 | 16 | Code of Ethics | Full verification |

| Energa Group | 2015 | 16 | Code of Ethics | Full verification |

| Energa Group | 2016 | 16 | Code of Ethics | No |

| Energa Group | 2017 | 27 | Code of Ethics | No |

| Energa Group | 2018 | 27 | Code of Ethics | Full verification |

| Energa Group | 2019 | 27 | Code of Ethics | Full verification |

| Company name | Report for Year | Environmental Management System | Quality Management System | Risk Management System | Corporate Governance Principles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fortum Power and Heat Polska | 2011 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| RWE Polska | 2010 | Yes | No | No | No |

| RWE Polska | 2012 | Yes | No | No | No |

| RWE Polska | 2013 | Yes | No | No | No |

| RWE Polska | 2014 | Yes | No | No | No |

| EDF Polska | 2013 | Yes | No | No | No |

| EDF Polska | 2014 | Yes | No | No | No |

| EDF Polska | 2015 | Yes | No | No | No |

| ZPUE Spółka akcyjna | 2017 | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| GPEC Group | 2016 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2011 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2012 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2016–2017 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2018–2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A | 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Polenergia S.A. | 2016 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Polenergia S.A. | 2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Polenergia S.A. | 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| PKP Energetyka | 2020 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Veolia Energia Polska | 2017 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Veolia Energia Polska | 2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| ENEA S.A. | 2011 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| ENEA S.A. | 2013 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| ENEA S.A. | 2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| ENEA S.A. | 2015 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| ENEA S.A. | 2016 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| ENEA S.A. | 2017 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| ENEA S.A. | 2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| ENEA S.A. | 2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| ENEA S.A. | 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2013–2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2015 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2017 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Energa Group | 2011 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Energa Group | 2013 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Energa Group | 2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Energa Group | 2015 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Energa Group | 2016 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Energa Group | 2017 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Energa Group | 2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Energa Group | 2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Company Name | Norms |

|---|---|

| Fortum Power and Heat Polska | ISO 14001 |

| RWE Polska | No data |

| EDF Polska | ISO 9001, ISO 14001 |

| ZPUE Spółka Akcyjna | ISO 9001, ISO 14001, ISO 45001 |

| GPEC Group | ISO 9001, ISO 14001 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | ISO 14001, ISO 26000 |

| Polenergia S.A. | ISO 14001, ISO 18001, ISO 26000 |

| PKP Energetyka | No data |

| Veolia Energia Polska | ISO 9001, ISO 14001, ISO 17025, ISO 27001, ISO 37001, ISO 45001, ISO 50001 |

| ENEA S.A. | ISO 9001, ISO 14001, ISO 18001, ISO 26000, ISO 45001 |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | ISO 14001 |

| Energa Group | ISO 14001, ISO 22300, ISO 26000, ISO 27001, ISO 37001, ISO 50001 |

| Criterion | Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Comprehensibility | The text is incomprehensible/unclear to the reader, the report contains numerous passages where industry jargon is used; some words of foreign origin are incomprehensible to the reader; there are no visuals or numerical data | Only 25% of the text is comprehensible/clear to the reader; some paragraphs are unclear to the reader; industry jargon is common; scarce use of visuals and numerical data | A half of the text is comprehensible/clear to the reader; there is some industry jargon and foreign-sounding words borrowed from other languages that are not entirely clear to the reader; the text is illustrated with few visuals and supplemented with small amounts of numerical data | Most (75%) of the text is comprehensible/clear to the reader; incomprehensible words are used only occasionally; the text is illustrated with visuals and supplemented with numerical data | The text is fully (100%) comprehensible/clear to the reader; it is richly illustrated with visuals; numerical data are available in a large quantity |

| Topicality | Descriptions are off-topic and address multiple issues; there are numerous digressions deviating from the issue in question; the narrative regularly deviates from the topic, exploring areas that are unrelated to the issue in question | Descriptions address the topic at only 25%; there are digressions unrelated to the issue in question; the narrative frequently deviates from the topic, exploring areas that are unrelated to the issue in question | Descriptions address the topic at 50%; some digressions are only indirectly related to the issue in question, although in some cases this is justified; the narrative occasionally does deviate from the topic, exploring areas that are indirectly related to the issue in question | Descriptions address the topic in 75%; there are few digressions and they are related to the issue in question, although in some cases this is justified; the narrative rarely deviates from the topic, exploring areas that are indirectly related to the issue in question | Descriptions address the topic 100% of the time; there are no digressions and the narrative does not deviate from the topic |

| Intertextuality (cross-references between financial and non-financial information on the one hand, and other information in the text on the other), = | Information does not relate in any way to information presented in other parts of the report; no references to other parts; the text is incoherent | Information is indirectly linked to information presented in other parts of the report; no references to the content in other parts of the report; the text is not very coherent | In some areas information is directly linked to the content of other parts of the report, whereas elsewhere the links are only indirect; due to the lack of regular cross-references, the coherence of the text is difficult to determine | Generally, information is directly linked to other parts the report; there are regular cross-references to other parts of the text; the text is coherent | Information is always directly linked to other parts of the report; there are numerous cross-references to other parts of the text; the text is highly coherent |

| Specificity | The text is very general, does not contain the required information; no numerical data | The text is rather general; information is superficial; numerical data are scarce | The text partially describes the required issues, but it still lacks detail; to some extent, numerical data are arithmetic expressions of the issue in question | The text is detailed; all the required issues are described; relevant numerical data are quoted at length | The text is very detailed; all the required issues are carefully described; relevant and detailed numerical data are available |

| Company Name | Report for Year | Comprehensibility | Topicality | Intertextuality | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fortum Power and Heat Polska | 2011 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| RWE Polska | 2010 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| RWE Polska | 2012 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| RWE Polska | 2013 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| RWE Polska | 2014 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| EDF Polska | 2013 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| EDF Polska | 2014 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| EDF Polska | 2015 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| ZPUE Spółka akcyjna | 2017 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| GPEC Group | 2016 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2011 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2012 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2016–2017 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2018–2019 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A | 2020 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Polenergia S.A. | 2016 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Polenergia S.A. | 2019 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Polenergia S.A. | 2020 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 |

| PKP Energetyka | 2020 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| Veolia Energia Polska | 2017 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Veolia Energia Polska | 2019 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2011 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2013 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2014 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2015 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2016 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2017 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2018 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2019 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2020 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2013–2014 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2015 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2017 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2018 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Energa Group | 2011 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Energa Group | 2013 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Energa Group | 2014 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| Energa Group | 2015 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Energa Group | 2016 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Energa Group | 2017 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Energa Group | 2018 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Energa Group | 2019 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Company Name | Report for Year | Comprehensibility | Topicality | Intertextuality | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fortum Power and Heat Polska | 2011 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| RWE Polska | 2010 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| RWE Polska | 2012 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| RWE Polska | 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| RWE Polska | 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| EDF Polska | 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| EDF Polska | 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| EDF Polska | 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ZPUE Spółka akcyjna | 2017 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| GPEC Group | 2016 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2011 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2012 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2016–2017 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2018–2019 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A | 2020 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Polenergia S.A. | 2016 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Polenergia S.A. | 2019 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Polenergia S.A. | 2020 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| PKP Energetyka | 2020 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Veolia Energia Polska | 2017 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 4 |

| Veolia Energia Polska | 2019 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 4 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2011 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2013 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2014 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2015 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2016 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2017 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2018 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2019 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2020 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2013–2014 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2015 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2017 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2018 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| Energa Group | 2011 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Energa Group | 2013 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Energa Group | 2014 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Energa Group | 2015 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Energa Group | 2016 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Energa Group | 2017 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Energa Group | 2018 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Energa Group | 2019 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Company Name | Report for Year | Comprehensibility | Topicality | Intertextuality | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fortum Power and Heat Polska | 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| RWE Polska | 2010 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| RWE Polska | 2012 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| RWE Polska | 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| RWE Polska | 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| EDF Polska | 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| EDF Polska | 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| EDF Polska | 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ZPUE Spółka akcyjna | 2017 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| GPEC Group | 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2011 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2012 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2016–2017 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2018–2019 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A | 2020 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Polenergia S.A. | 2016 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Polenergia S.A. | 2019 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Polenergia S.A. | 2020 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| PKP Energetyka | 2020 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| Veolia Energia Polska | 2017 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| Veolia Energia Polska | 2019 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2011 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2013 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2014 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2015 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2016 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2017 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2018 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2019 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2020 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2013–2014 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2015 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2017 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2018 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| Energa Group | 2011 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Energa Group | 2013 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Energa Group | 2014 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Energa Group | 2015 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Energa Group | 2016 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Energa Group | 2017 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Energa Group | 2018 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Energa Group | 2019 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Company Name | Report for Year | Comprehensibility | Topicality | Intertextuality | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fortum Power and Heat Polska | 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| RWE Polska | 2010 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| RWE Polska | 2012 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| RWE Polska | 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| RWE Polska | 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| EDF Polska | 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| EDF Polska | 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| EDF Polska | 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ZPUE Spółka akcyjna | 2017 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| GPEC Group | 2016 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2012 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2016–2017 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A. | 2018–2019 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Tauron Polska Energia S.A | 2020 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Polenergia S.A. | 2016 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| Polenergia S.A. | 2019 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Polenergia S.A. | 2020 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| PKP Energetyka | 2020 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| Veolia Energia Polska | 2017 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Veolia Energia Polska | 2019 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2016 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2017 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2018 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2019 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| ENEA S.A. | 2020 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2013–2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2015 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2017 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna | 2018 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Energa Group | 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Energa Group | 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Energa Group | 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Energa Group | 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Energa Group | 2016 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Energa Group | 2017 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Energa Group | 2018 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Energa Group | 2019 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bartoszewicz, A.; Szczepankiewicz, E.I. Evolution of Energy Companies’ Non-Financial Disclosures: A Model of Non-Financial Reports in the Energy Sector. Energies 2022, 15, 7667. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15207667

Bartoszewicz A, Szczepankiewicz EI. Evolution of Energy Companies’ Non-Financial Disclosures: A Model of Non-Financial Reports in the Energy Sector. Energies. 2022; 15(20):7667. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15207667

Chicago/Turabian StyleBartoszewicz, Anna, and Elżbieta Izabela Szczepankiewicz. 2022. "Evolution of Energy Companies’ Non-Financial Disclosures: A Model of Non-Financial Reports in the Energy Sector" Energies 15, no. 20: 7667. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15207667

APA StyleBartoszewicz, A., & Szczepankiewicz, E. I. (2022). Evolution of Energy Companies’ Non-Financial Disclosures: A Model of Non-Financial Reports in the Energy Sector. Energies, 15(20), 7667. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15207667