Abstract

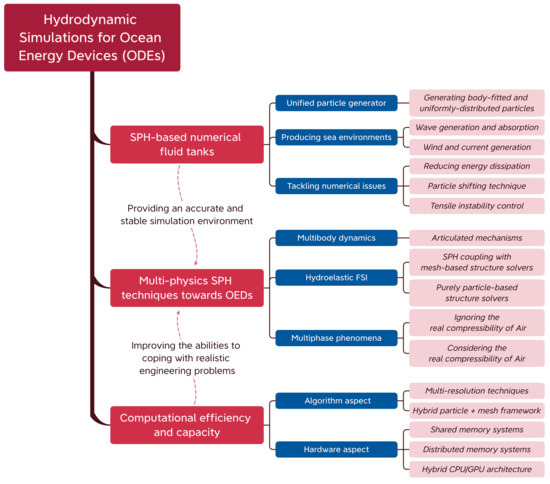

This article is dedicated to providing a detailed review concerning the SPH-based hydrodynamic simulations for ocean energy devices (OEDs). Attention is particularly focused on three topics that are tightly related to the concerning field, covering (1) SPH-based numerical fluid tanks, (2) multi-physics SPH techniques towards simulating OEDs, and finally (3) computational efficiency and capacity. In addition, the striking challenges of the SPH method with respect to simulating OEDs are elaborated, and the future prospects of the SPH method for the concerning topics are also provided.

Keywords:

smoothed particle hydrodynamics; ocean energy devices; floating wind turbines; wave energy converters; tidal current turbines; unified particle generator; numerical fluid tanks; particle shifting techniques; tensile instability control; multi-physics SPH simulations; multibody dynamics; fluid-structure interactions; hydroelasticity; multiphase flows; air-entrainment; parallel computing; multi-resolution; open-source SPH packages 1. Introduction

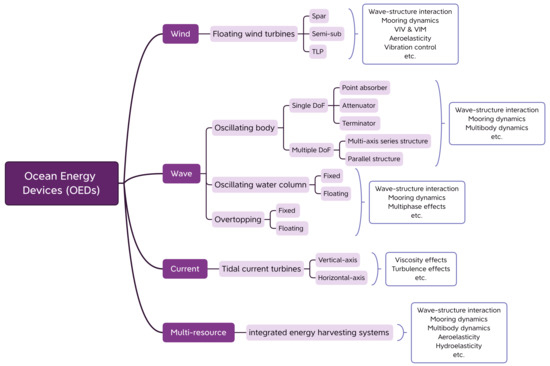

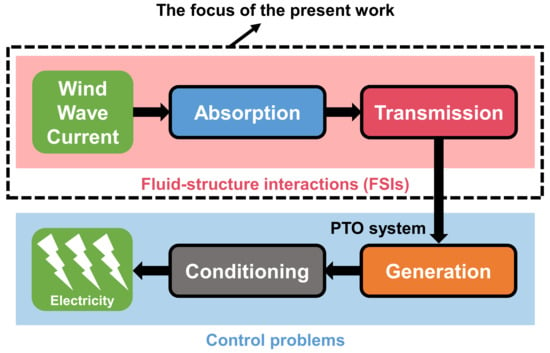

During the past several decades, renewable energy has become the most significant resource for human activities because of the worldwide awareness of the depletion of traditional fossil fuels as well as their harmful impacts on human’s living environment [1]. Among various types of renewable energy, ocean energy has been regarded as the preferred one to tackle the dilemma of humans owing to its abundant storage and, more importantly, its very low carbon dioxide emissions [2]. Since the capture and exploitation of ocean energy started to receive attention by the scientific and industrial communities [3], the technologies for harnessing ocean energy have been investigated and developed significantly to meet the energy market, which considerably fosters the invention of diverse Ocean Energy Devices (OEDs) ranging from small-scale isolated apparatus [4] to large-scale Integrated Energy Harvesting Systems (IEHSs) [5,6]. Generally speaking, as shown in Figure 1, the classification of OEDs can be mainly categorized by their energy resource, i.e., winds (e.g., Floating Wind Turbines, FWTs) [7,8,9,10], waves (e.g., Wave Energy Converters, WECs) [11,12,13], currents (e.g., Tidal Current Turbines, TCTs) [14,15,16], and multi-resource (see e.g., [6]). As pointed out by Said and Ringwood [17], ordinary OEDs consist of four phases to converting ocean energy to electricity (see also Figure 2), namely, absorption, transmission, generation, and conditioning. Among them, the absorption and transmission phases are typically characterized by Fluid–Structure Interaction (FSI), whereas the generation and conditioning phases mainly involve control strategies. Each phase has its scientific problems, and the present work is particularly devoted to the FSIs phases as illustrated in Figure 2. For the control problems, the readers can refer to [18].

Figure 1.

A popular classification of various OEDs (inspired from [13]) and the typical hydrodynamic problems associated with them.

Figure 2.

The working pipeline of a generic OED (adapted from [17]), and the focus of the present study.

In fact, all of the aforementioned OEDs (see also Figure 1) can be treated as a special group of general nearshore/offshore structures that are widely employed in coastal and ocean engineering for diverse human activities, while there are several differences between OEDs and those traditional ones (e.g., vessels and platforms) from the hydrodynamic point of view. For example, traditional floating structures usually require minimum motion response during their working stage to guarantee the safety of both the staff and apparatuses, whereas for the sake of efficiently converting the mechanical energy of fluids to electricity by the Power Take-Off (PTO) system of them [19], OEDs are often expected to possess maximum motion responses in a diverse sea environment, e.g., working at a resonance status (see, e.g., [20,21,22]). Another example is that the aeroelasticity always imposes negligible effects on traditional offshore structures, while this is not the case when evaluating the working performance of FWTs, on which the coupling between flexible blades and air has strong nonlinear effects [23,24,25], thereby affecting their ability for generating electricity. In addition to these differences, those hydrodynamic problems originating from traditional offshore structures also widely exist in OEDs, e.g., hydroelasticity (see, e.g., [5,26,27]), wave slamming (see, e.g., [28,29]), Vortex-Induced Vibration/Motion (VIV and VIM) (see, e.g., [30,31,32]), multibody interactions (see, e.g., [33,34]), vibration control (see, e.g., [35,36]), viscosity and turbulence effects (see, e.g., [37,38,39,40]), and mooring dynamics (see e.g., [41,42]). Therefore, the hydrodynamic problems regarding OEDs are typically characterized by strongly nonlinear multi-physics coupling, which is, to a large extent, even more complicated than that of traditional coastal and ocean engineering structures. Because of the complexity and nonlinearity, during the past decades, the hydrodynamic performance of various OEDs has been considerably investigated to obtain the best ability of power generation under diverse real-sea environments (see, e.g., [7,9,13,15,16,19]).

Similar to other ocean engineering structures, the methodologies to investigate the hydrodynamic performance of OEDs can be mainly categorized into three types, i.e., a theoretical method (also named an analytical or semi-analytical method), an experimental method, and a numerical method. In terms of the theoretical method, it mainly relies on potential flow theory where linearized (or nonlinearized), incompressible, irrotational, and inviscid assumptions are always adopted (see, e.g., [19,43,44]). Nonetheless, as mentioned above, the concerning field is featured by strong nonlinearity and multi-physics coupling, so that the theoretical method seems a less ideal tool when considering complex working conditions, for example, large body motion (e.g., Oscillating Wave Surge Converters (OWSCs) [45,46]), multiphase flows (e.g., FWTs and Oscillating Water Columns (OWCs) converter), viscosity, and turbulence (e.g., FWTs and TCTs). In terms of the experimental method, it can be further divided into real-sea tests (see, e.g., [47,48]) and model tests (see, e.g., [49,50,51]). There is no doubt that a full-scale experiment is one of the best measures to evaluate the hydrodynamic performance of OEDs because it can reproduce the realistic working environment without any simplifications and scaling effects. However, full-scale tests are always very expensive, and the processing of the prototype of OEDs is not trivial. As a consequence, model tests are preferred by the engineering communities because of their relatively lower costs and higher feasibility. Notwithstanding, the reliability of model tests is particularly constrained by scaling effects since it is impossible to simultaneously satisfy the Froude and Reynolds similarity in a laboratory experiment (see, e.g., [52,53,54]). On the other hand, although model tests are cheaper than full-scale tests, it remains expensive compared with other methods. Therefore, the last one (i.e., the numerical method) is preferred at the pre-design stage of OEDs.

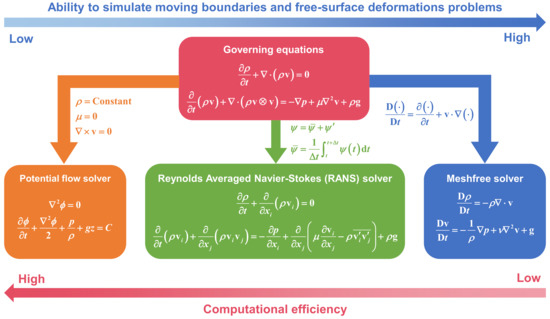

The numerical method is also known as Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) in the literature; it has been boosting during the past decades owing to the prosperous semiconductor industry that fosters the development of computer hardware. Although extensive CFD tools have been developed on both open-source platforms and commercial packages, only three types of CFD have been widely adopted for simulating OEDs, i.e., the Potential Flow (PF) solver, the Reynolds Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) solver, and the meshfree solver (see also Figure 3). Among them, PF, usually implemented by the Boundary Element (BE) approach, is the most computationally efficient one because it only requires a boundary grid on the OEDs surfaces. However, due to the linearized, irrotational, and inviscid hypotheses, PF is not suitable to be applied to violent free-surface breaking or viscosity-dominated problems. In order to deal with the deficiencies of PF, RANS was thereby developed by modeling the turbulence effects using the time-averaging approach, retaining the fully nonlinear characteristics of the Navier–Stokes equation. There is no doubt that RANS possesses better accuracy and applicability than PF because of its nonlinearity and viscosity consideration, whereas its computational cost is considerably greater than PF. Despite its remarkable advantages and successful applications in designing OEDs (see, e.g., [55,56,57,58,59]), RANS undergo several striking issues in some circumstances caused by its Eulerian nature. Among them, the two most challenging issues are (1) the accurate capture of highly distorted topological deformations and (2) the prevention of the over-dissipation of dynamic multiphase interfaces (or fluid jets and droplets). In terms of the former, for example, when multibody dynamics systems are involved, it is difficult to simulate such complicated coupling behaviors via mesh methods, although this could be realized by using the numerical technique known as the Overset Mesh. However, the flow information should be interpolated via the interfaces between the overset region and the background region, which could result in some discontinuities of the field quantities and could thus reduce the numerical accuracy and stability. Another drawback is that in those regions characterized by violent free-surface evolutions, e.g., wave breaking/slamming in the vicinity of OEDs (see Figure 20), mesh methods could provide inaccurate numerical results caused by their over-dissipation characteristic (i.e., mass non-conservation). Considering the aforementioned two deficiencies, it is in favor of using the meshfree method to remove the dilemma.

Figure 3.

A brief comparison of the most popular numerical methods for simulating OEDs. For more details regarding these governing equations, the readers can refer to the textbooks [60,61,62].

The meshfree method has been considerably investigated and developed during the past decades owing to their distinct superiorities compared with mesh methods, e.g., easy-to-model moving boundaries and capture free-surface fragmentation. Among them, the Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) method is one of the most promising truly meshfree methods. The SPH method was initially proposed for astronomy simulations in 1977 by Gingold and Monaghan [63] and Lucy [64]. Since the very early years of the 1990s, the SPH method began to be applied to violent free-surface evolutions due to its Lagrangian nature that is inherent to be suitable for such problems. Especially, after the pioneering work conducted by Monaghan in 1994 [65], the SPH method has witnessed its surprising advances in tackling coastal and ocean engineering problems, of course for OEDs simulations as well. Although extensive literature regarding simulating OEDs using the SPH method was published during the past decades, to the best knowledge of the authors, it still lacks an effort dedicated to providing a detailed review of this field. Note that although several reviews have been focused on the SPH applications towards coastal and ocean engineering (see, e.g., [66,67]), free-surface flows (see, e.g., [68,69,70,71,72]), multiphase flows (see e.g., [73]), FSI problems (see, e.g., [74,75,76,77]), and diverse industrial applications (see, e.g., [78,79,80,81,82,83]), these works paid little attention to OEDs, for which several hydrodynamic problems are quite different from traditional nearshore/offshore structures and thereby deserve energy engineers and SPH practitioners’ attention. Therefore, in contrast to the previous reviews, this study aimed at offering the state-of-the-art progress with regard to various advanced SPH techniques in the hydrodynamic predictions of OEDs towards industrial applications, and the attention of the present work is particularly focused on the following topics (see Figure 4 for more details)

Figure 4.

The outline of the present article.

- 1.

- SPH-based numerical fluid tanks.

- 2.

- Multi-physics SPH techniques for simulating OEDs.

- 3.

- Computational efficiency and capacity.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. In Section 2, the governing equations of the fluid and the fundamental concepts of the SPH method are briefly recalled. In Section 3, the latest development of SPH-based numerical fluid (including wind, wave, and current) tanks are reviewed. In addition to that, the attention of this section is also focused on how to accurately deal with the numerical issues including (1) disordered particle distribution, (2) tensile instability, and (3) the over-attenuation of wave propagation. Section 4, Section 5 and Section 6 are devoted to stating the up-to-date multi-physics SPH techniques towards simulating OEDs, including (1) the multibody dynamics with a mooring system, (2) hydroelastic FSIs, and (3) multiphase flows. Subsequently, in Section 7, how to improve computational efficiency and capacity via diverse techniques from the algorithm and hardware aspects are discussed, which are significant for simulating OEDs because such a type of SPH simulations is usually characterized by a huge computational domain and a substantial total particle number. Finally, conclusions and future prospects of the concerning topics are illustrated in the last part of the article.

2. A Brief Recall of the SPH Method for Simulating Hydrodynamic Problems Related to OEDs

In order to ensure the completeness of the article, in this section, we offer a brief recall with respect to the governing equations of the fluid and the fundamental concepts of the SPH method; for a comprehensive description of the methodology, the readers can refer to classical textbooks (see, e.g., [62,84]).

2.1. Governing Equations: Weakly Compressible and Truly Incompressible Hypotheses

2.1.1. Weakly Compressible Hypotheses

In the weakly compressible hypotheses, the pressure and density of the fluid can be decoupled via a stiff Equation of State (EoS). Therefore, the governing equations of the fluid can be written as the following Lagrangian formalism (see, e.g., [79,85]).

represents the Lagrangian/material derivative, and the subscript 0 denotes the reference value of the acted variable. , p, , and denote the density, pressure, kinematic viscosity, and velocity vector of the fluid, respectively. signifies gravitational acceleration. stands for the polytropic coefficient, which is usually adopted as and for water and air (see, e.g., [86,87]), respectively. signifies the reference density at rest. is a pseudo sound speed, which is normally adopted as 10 times higher than the anticipated maximum fluid velocity, , for the sake of reducing the density variation down to 1%, i.e., [85]. Note that if the value of is set to 1, the EoS can be simplified to . This simplification was firstly used by Morris et al. [88], showing more stability within the WCSPH framework.

One of the greatest superiorities of WCSPH is its fully explicit property in time, which means that the velocity, position, and density of fluid particles can be updated straightforwardly via

and

where denotes the position vector of the fluid and the time step. The superscript of n and denote the n-th and -th time steps, respectively. Finally, the pressure can be obtained by the EoS through the updated density. Practically, to ensure numerical stability, the predictor-corrector method or Roung–Kutta time integrations are often adopted (see more details in Section 2.3).

2.1.2. Truly Incompressible Hypotheses

Conversely, the governing equations for the truly incompressible fluid become

To enforce incompressibility and solve the Pressure Poisson Equation (PPE), the procedure proposed by Cummins and Rudman [89] has been generally adopted in the SPH community (see, e.g., [90,91,92,93]), which was inspired by Chorin’s projection method [94] with an adapted form. This method consists of two steps, i.e., the prediction and correction steps. The prediction step is to calculate the intermediate velocity, , based on the viscosity and gravity forces via

Subsequently, the correction step can be implemented based on the pressure force via

Finally, the intermediate velocity can be projected on the divergence-free space by writing the divergence of Equation (6), which yields the following PPE

where signifies the Laplacian operator. Once the pressure is obtained from PPE, the velocity and position at the -th step can be updated via

2.1.3. Weakly Compressible or Truly Incompressible: The Best Choice towards OEDs Simulations

Traditionally speaking, in the early years, SPH practitioners were in favor of using ISPH rather than WCSPH for coastal and ocean engineering simulations owing to its inherent noise-free characteristic. For example, in 2008, Lee et al. [91] carried out a detailed investigation on the differences between WCSPH and ISPH. It was concluded that ISPH can provide much smoother velocity and pressure fields than WCSPH in every case they implemented; these were also proved and supported by other researchers (see, e.g., [95,96]).

To reduce the spurious numerical noise of WCSPH, several measures have been proposed over the years. The related pioneering work can be traced back to Monaghan and Gingold [97], where an artificial viscosity term based on a Neumann–Richtmeyer viscosity was proposed to alleviate the oscillations induced by shock waves. The next breakthrough corresponds to Colagrossi and Landrini [86], where a Mean Least Square (MLS) integral interpretation was introduced to filter the oscillating density field. Although this scheme can provide good results, it cannot be applied to long-term simulations because the hydrostatic component of the fluid system is nonphysically filtered, leading to the non-conservation of total fluid volume [98,99]. Further, Molteni and Colagrossi [100] proposed to use a numerical diffusive term inside the continuity equation; this term can give good results but fails also to produce the hydrostatic solution. Consequently, the authors deactivated the diffusive term when the pressure is below the hydrostatic solution, which weakens the effectiveness of the diffusive term. Fortunately, this issue was successfully resolved by Antuono et al. [98] in 2010, resulting in the -SPH model that produces an excellent density/pressure solution in most cases; this work was further extended to violent free-surface flows by Marrone et al. [101] in 2011. There is no doubt that after being proposed, the -SPH model almost became the standard form for WCSPH; these works were also awarded with the Monaghan Prize in 2018 by SPH Research and Engineering International Community (SPHERIC)) for their outstanding contributions to the SPH community [102].

Although ISPH shows better performance in tackling incompressible flow problems, three issues pose some limitations in simulating OEDs. Firstly, ISPH must solve PPE that is implicit in time, which is not straightforward to code compared with WCSPH. Secondly, ISPH demands the explicit detection of the free-surface to impose the dynamic free-surface boundary condition that is implicitly fulfilled in WCSPH (see, e.g., [103]). Finally, the most striking one is that ISPH is hard to be applied to a large-scale simulation accelerated by the Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) parallelization, especially for the 3D simulations towards realistic industrial applications (see, e.g., [104]). The root is that the required memory of ISPH will be largely occupied by storing the exponentially increasing elements of the PPE matrix as the total particle number increased. In other words, the computational capacity of ISPH could be far smaller than WCSPH when the GPU parallelization is employed. Nonetheless, WCSPH is free from this issue because its required memory grows linearly as the increase in total particle number due to the fully explicit property in time. Therefore, only a few efforts have been dedicated to implementing ISPH on GPU (see, e.g., [104,105,106]).

It should be kept in mind that the simulations of OEDs usually involve the FSI process between water waves and complex structures (even an array of OEDs), which usually requires (1) a huge computational domain to prevent possible nonphysical reflected waves from borders and (2) sufficiently refined particle resolution to accurately capture the spatiotemporal free-surface evolutions, meaning that the total particle number could be substantial in such a type of SPH simulations. From this point of view, WCSPH is now more feasible than ISPH considering the balance between numerical accuracy and computational efficiency/capacity. This is why the present popular GPU-based open-source SPH solvers (e.g., DualSPHysics [107] and GPUSPH [108]) have adopted WCSPH rather than ISPH as their solver framework. Therefore, in the following discussions, attention is particularly focused on WCSPH; for classical literature regarding ISPH, the readers can refer to [89,90,92,93].

2.2. The Fundamental Concepts of SPH

2.2.1. Kernel and Particle Approximations

In the SPH method, the discrete governing equations can be constructed following two steps, i.e., the kernel approximation and particle approximation (see, e.g., [75,78]). The kernel approximation aims to evaluate field qualities and their spatial derivative (i.e., gradient and divergence) via the kernel function as

where and represent the generic scalar and vector functions, respectively. and stand for the targeted position and its neighboring points, respectively. signifies the kernel function to approximate the reciprocal contribution between two points of interest with h being the smoothing length. denotes the infinitesimal integral element. Note that owing to the compact support property of the kernel function, the integrals of Equations (9)–(11) vanish in those regions beyond the support domain denoted by .

Considering the kernel property of

Equations (13) and (14) are preferred by SPH practitioners since this formalism could somewhat reduce the kernel truncation on boundaries. In order to transform the kernel approximation into the particle approximation, the computational domain should be discretized into several particles that carry all field quantities of the flow region. Note that a lumped volume defined as is imposed to each particle at every time step with being the invariant particle mass of the i-th particle given at the initialization; this means that these particles do not have a fixed volume (or shape) and therefore could trigger the particle Lagrangian structures behaving as the particle clumping and clustering phenomenon during an SPH simulation; this will be further discussed in Section 3.3.1.

Subsequently, by summing up the overall neighboring particles within the support radius of the i-th particle, Equations (9), (13), and (14) can be rewritten from the continuous form to the discrete form as

respectively, where the subscripts i and j refer to the targeted particle and its neighboring particles, respectively. The subscript i in denotes that the acted variable is evaluated with respect to the i-th particle. is adopted hereafter for brevity.

2.2.2. Discrete Governing Equations: The WCSPH Model

According to Equations (15)–(17), system (1) can thereby be converted into the following popular WCSPH formalism

where and stand for the density diffusive term and the viscosity term, respectively. and denote the anticipated maximum velocity and pressure in the flow domain, respectively. As discussed in Section 2.1.3, the most popular density diffusive term is the -term given as [98]

where refers to the renomalized density gradient [109] that can recover the particle consistency in the vicinity of boundaries. For more details regarding the -term, the readers can refer to [98,101].

Regarding the viscosity term, as suggested by Monaghan and Gingold [97], when an inviscid fluid assumption is adopted, an artificial viscosity term should be employed to improve the robustness of an SPH simulation. On the contrary, when considering the physical viscosity (e.g., foil hydrodynamics), the artificial viscosity can be directly converted into the physical one because the former is equivalent to a Neumann–Richtmeyer viscosity [85,97]. can be written as

where with n being the dimension of the simulation. is given as

where is expected to prevent a zero denominator.

In addition to the -SPH model, another popular WCSPH model is the Riemann-SPH that employs a Riemann solver into the governing equations to stabilize the calculation and alleviate the nonphysical pressure noise. The governing equations of the Riemann-SPH model can be written as (see, e.g., [110])

where and are the solutions of an inter-particle Riemann problem along with the vector pointing from the i-th particle to the j-th particle (see, e.g., [111,112]). The Riemann-SPH solver can provide accurate pressure field comparable to the -SPH model; therefore, in the present SPH community, both the -SPH and Riemann-SPH have been widely employed to solve engineering problems [113,114]. Typical examples are DualSPHysics with -SPH [107], SPHinXsys [112] and Nextflow Software [115] with Riemann-SPH.

2.3. Time Integration

Regarding time integration, several schemes are available in the SPH literature such as the Verlet or Symplectic schemes (see, e.g., [107,112]), the 4th-order-Runge–Kutta (RK4) scheme (see, e.g., [99,116]), and the prediction-correction scheme (see, e.g., [117]). No matter which time-integration scheme is adopted, the time step, , should be determined by the Courant–Friedrich–Levy (CFL) condition as (see, e.g., [112,118,119,120]).

where denotes the kinematic viscosity of the fluid. Note that the value of CFL can be up to in RK4 because of its high-order accurate property, while in other second-order accurate schemes, this value has been usually adopted as to stabilize the simulation. For instance, in DualSPHysics the default value of CFL is 0.3 [107], and in SPHinXsys the default values of CFL are 0.25 and 0.6 for the advection criterion and the acoustic criterion [112], respectively, whereas in those simulations adopting RK4, the value of CFL has been usually adopted as 1.0∼1.25 (see, e.g., [118,119]). From this point of view, although RK4 requires more sub-steps for each time step, its computational costs would not increase apparently due to the larger value of CFL.

2.4. Boundary Conditions

2.4.1. Free-Surface Boundary Condition

In the context of OEDs simulations using WCSPH, the most important two boundary conditions are the (1) free-surface boundary and (2) wall boundary for most cases. In terms of the free-surface boundary, it can be further categorized into the Kinematic and Dynamic Free-surface Boundary Condition, i.e., KFSBC and DFSBC, respectively. Because the SPH method is a purely Lagrangian numerical scheme, KFSBC is naturally satisfied without any extra requirements. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated by Colagrossi et al. [103] that in the WCSPH scenario, DFSBC can also be implicitly satisfied because and in the free-surface. However, the authors have also pointed out that the formalism of SPH operators imposes significant effects on the convergence properties for simulating free-surface problems (for more details, the readers can refer to [103]). Therefore, only the wall boundary should be taken into account by SPH practitioners in WCSPH simulations.

2.4.2. Wall Boundary Condition

Generally speaking, in the SPH framework, the wall boundary condition can be enforced by two methods. One way is to distribute particles on wall surfaces to complete the kernel support near the boundary, which is the most popular method in the present SPH community. For example, the technique named Fixed Ghost Particle proposed by Adami et al. [121] was adopted in SPHinXsys or Dynamic Boundary Condition by Crespo et al. [122,123] in DualSPHysics. Another method is based on the normal-flux method that discretizes physical walls into several segments, i.e., line elements in 2D and triangle elements in 3D; this method was adopted by several commercial SPH packages, such as Nextflow Software [115] and Dive Solution [124]. It should be highlighted here that which method is the best choice for simulating OEDs is still an open topic for the SPH community because both of the two methods have their superiorities. In terms of the normal-flux method, it could save a significant amount of time in the pre-process stage because the only required file is just geometry data (e.g., STL-format file); this method facilitates accurately modeling arbitrarily complex 3D structures as proved by Chiron et al. [125]. On the contrary, the particle-based wall boundary is strongly limited by the particle generation because it is hard to obtain high-quality particles needed by SPH simulations, whereas it facilitates the generality and extendibility of SPH codes because the solver can be developed in a unified Lagrangian particle framework. Besides, a particle-based wall boundary can be implemented without any extra requirements to tackle the fluid–structure interfaces, improving the numerical accuracy and stability for SPH simulations.

There is no doubt that compared with generating high-quality particles on body surfaces, creating grids for complex 3D structures is more easy-to-realize because there have been substantial open-source (e.g., OpenFoam [126] and TetGen [127]) and commercial (e.g., Altair Hypermesh and ANSYS ICEM) packages that can cope well with this. Therefore, in this subsection, attention is particularly focused on several feasible methods to generate body-fitted and uniformly distributed particles, which is the most important pre-process technique for simulating OEDs when a unified particle framework is considered.

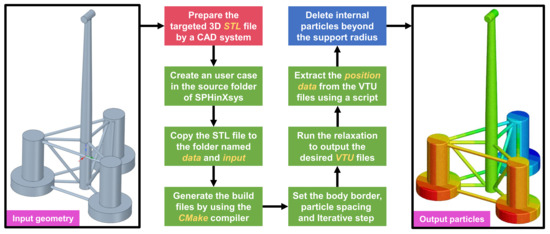

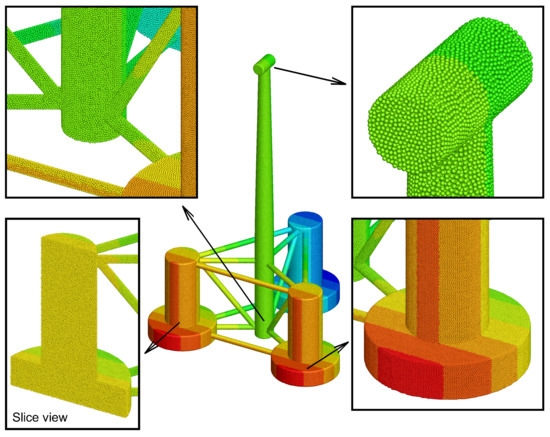

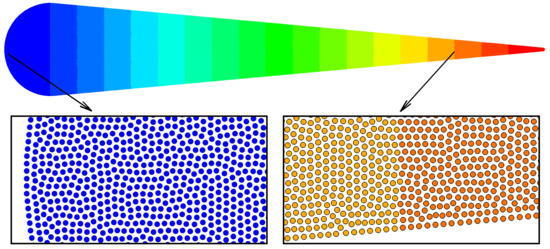

It is evident that creating body-fitted and uniformly distributed particles on body surfaces is not trivial for SPH practitioners. The pioneering work for proposing a generic-purpose particle-generating technique can be traced back to Colagrossi et al. [128], where the Particle-Packing Algorithm (PPA) was elaborated. As demonstrated by the authors, PPA can be embedded without difficulty into whatever WCSPH or ISPH codes since the algorithm is proposed directly based on some intrinsic features of the SPH method (see [128] for more details). Nevertheless, to the best knowledge of the authors, there has been no user-friendly open-source particle generator developed based on PPA. Another accessible particle-generating technique is the CAD-BPG that has been proposed by Zhu et al. [129] in 2021. In this technique, to achieve body-fitted and uniformly distributed particles on wall surfaces, a physics-driven relaxation process governed by a transport-velocity is employed to characterize the particle evolutions; this procedure is now integrated on the latest version of SPHinXsys [112], showing excellent ability and user-friendly properties for creating body-fitted particles for arbitrarily complex 3D structures. Figure 5 displays the general procedure for creating body-fitted particles for a semi-submersible FWT using the CAD-BPG solvers, while in Figure 6 several zoom-in views of the output FWT’s particles are illustrated to demonstrate the high-quality particle distribution provided by the particle generator. One can see that the solver is easy to use, and the resulting particles show a quite homogeneous characteristic that facilitates the numerical accuracy and stability of SPH simulations. Of course, the solver can also be applied to arbitrarily complex 2D structures; a typical example for a 2D hydrofoil is shown in Figure 7. Note that for generating 2D particles, instead of using a 3D STL file, the required file is a dat file containing the coordinate information of the border of the targeted 2D body (for more details, the readers can refer to the tutorial documents of SPHinXsys).

Figure 5.

The pipeline of CAD-BPG: an example for generating the body-fitted and uniformly distributed particles of a semi-submersible FWT.

Figure 6.

The zoom-in view of the FWT’s particles. The color represents the x-axis position.

Figure 7.

The body-fitted and uniformly distributed 2D particles generated by the CAD-BPG solver: an example of a 2D hydrofoil. The color represents the x-axis position.

Of course, to simulate OEDs, other boundary conditions such as the wavemaker boundary for generating water waves and the inlet/outlet boundary for generating winds and currents are also very important, which will be further discussed in Section 3.

3. Numerical Fluid Tank Based on SPH for Simulating Hydrodynamic Problems Related to OEDs

In the context of coastal and ocean engineering, establishing accurate and robust numerical fluid tanks (NFTs) to generate targeted waves, currents, and winds is the most significant prerequisite for FSIs simulations. As discussed in Section 1, traditional Eulerian mesh-based NFTs, e.g., Finite Volume (FV) and Finite Difference (FD), are mature algorithmically, and this type of NFTs can be efficiently established by either using commercial packages (e.g., Siemens STAR-CCM+ and ANSYS Fluent) or open-source codes (e.g., OpenFoam [126]). Notwithstanding, because of their inherent Eulerian nature, mesh-based NFTs usually suffer from some unwanted numerical issues, e.g., the non-conservation of total fluid mass and the over-dissipation of multiphase interfaces. For example, the air–water interfaces are prone to be violently blurred when the mesh resolution of the multiphase interfaces is insufficient, although this could be partly prevented by implementing the Adaptive Mesh Refinement (AMR) technique that refines the mesh resolution in the proximity of multiphase interfaces and consequently provides better sharpness of the phase borders. Nonetheless, as a truly meshless method, SPH is totally free from the aforementioned issues thanks to its Lagrangian characteristic. In fact, Christian et al. [130] have already provided a comprehensive review regarding the high-fidelity numerical wave tanks (NWTs) towards WECs mainly focusing attention on various mesh methods. Differing from that work, in this section, attention is particularly concentrated on how to accurately generate not only water waves but also winds and currents by using the SPH method. Furthermore, several feasible and effective strategies to remove some numerical issues are elaborated, including the over-dissipation of wave energy, anisotropic particle distribution, and tensile instability.

3.1. Wave Tank

3.1.1. Wave Generation

In terms of OEDs, especially for WECs and FWTs, wave excitations are the most critical environmental loads during working. Therefore, an accurate and robust NWT is the base of any numerical method aiming at coastal and ocean engineering purposes. Generally speaking, as outlined by Higuera et al. [131], the numerical wave-generation methods can be categorized into three types, i.e., an internal method, a static-boundary method, and a moving boundary method.

The internal method is also known as the internal wavemaker, which was proposed to add an artificial source term into the continuity/momentum equations to mimic a wavemaker. The superiority of the internal method is avoiding undesired wave reflections from the wave-making boundary [132], whereas it could lead to extra computational costs because of the need of extending the flow domain [67]. For the typical examples of this method using SPH simulations, the readers can refer to [132,133].

In terms of the static boundary, its main idea is to straightforwardly implement Dirichlet conditions for the wave-generation boundary. In this method, the wave-making boundary is handled by different analytical wave theories, giving the anticipated velocity and free-surface elevations to produce the targeted incoming waves [131]. It is evident that this method is naturally suitable for Eulerian mesh-based solvers, whereas in the Lagrangian meshfree framework it is hard to be implemented because the particle position evolves according to the governing equations as time integration. Therefore, scarce attempts have been devoted to this method within the SPH framework, although it is widely applied in mesh-based solvers such as the PF and RANS models.

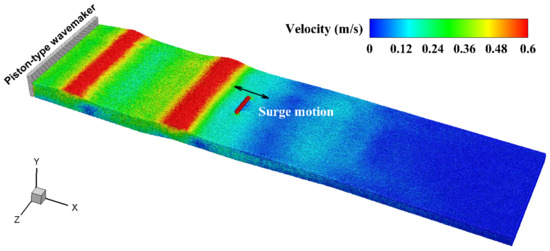

As can be seen, the aforementioned methods are purely based on a numerical aspect to generate water waves, while the final approach, i.e., the moving boundary method, directly produces water waves via a realistic boundary motion just as the actual wavemaker machines in laboratory experiments. This method, indeed, has been not so common for Eulerian mesh-based solvers since it requires large mesh deformation, which is one of the striking weaknesses of Eulerian methods. However, in meshless approaches such as the SPH method, the implementation of the moving boundary is straightforward without any extra requirements [134]. Therefore, this method is strongly recommended in the SPH simulation of the wave–structure interactions for OEDs; this method has also been adopted by several open-source SPH solvers such as DualSPHysics [107,134] and SPHinXsys [112,135]. Note that for the sake of brevity, in the following discussion, the term of wavemaker especially denotes the moving-boundary method.

The earliest work to use the wavemaker for generating water waves within the SPH framework could be traced back to Monaghan in 1994 [65], where a piston-type wave paddle was employed to produce several water waves. After that, various numerical techniques for producing different types of water waves were investigated, e.g., piston-type [134] and plunger-type [136,137]. For example, Altomare et al. [134] conducted a comprehensive investigation on regular and irregular water-waves generation using a piston-type wavemaker. Sun et al. [138] produced the focusing waves (or freak waves) also using a piston-type wavemaker to study the wave–structure interactions. He et al. [136] realized the solitary-waves generation by employing a plunger-type wavemaker. For a brief summary, the moving-boundary method is now mature for generating various types of water waves, ranging from regular to irregular waves and from linear to nonlinear waves. Therefore, it is recommended for simulating OEDs on account of its higher applicability and versatility compared with other wave-making methods.

3.1.2. Wave Absorption

The wave absorption also plays an important role in NWTs because NWTs are always constructed with limited overall length and width to reduce computational costs, which could trigger wave reflections from the wall boundaries or wave paddles and thereby could largely reduce the quality of the generated water waves. Hence, numerical techniques are needed to tackle the wave reflections.

Traditionally, passive absorbers are the most common techniques for wave absorption, which can be implemented by two methods. One consists of placing a sloping bottom or porous structures in front of the boundaries of interest where large wave reflections could exist; this method is similar to those used in physical tests. However, this type of absorption system is usually very sensitive to specific wave parameters, lacking versatility for different types of water waves. Another method is more simple but effective, i.e., implementing a damping zone into the computational domain. In this damping region, the particle kinetic energy can be dissipated rapidly by different mechanisms, e.g., improving viscosity or reducing velocity. For instance, in the SPH simulations conducted by Sun et al. [138], a viscosity damping zone in front of the end boundary of the tank was built by increasing the artificial viscosity coefficient of the zone. Another example is that Lind et al. [92] employed a velocity damping zone to dissipate the wave energy at the end of a wave tank by an exponentially decaying scheme.

Although passive absorbers show remarkable convenience and performance in practical applications due to their simplicity, it could be not enough when a long-term SPH simulation of wave–structure interactions is performed. The main reason is that in such a simulation, the water waves could be reflected towards the wave paddle and thereby contaminate the SPH results. Consequently, another method, i.e., active absorbers was proposed to tackle this issue. There are various techniques available for this method depending on the feedback of specific field quantities, for example, the free-surface elevations in front of the wavemaker or the force acting on the wavemaker. One typical attempt corresponds to DualSPHysics [107], where the active absorbers have been implemented by using the free-surface evolutions at the wavemaker position as the feedback [134].

On the whole, when a short-term SPH simulation involving water waves is performed, both the passive and active absorbers can be employed. On the contrary, it is in favor of implementing active absorbers to achieve the best quality of wave generation [134].

3.1.3. Wave Energy Attenuation

When an NWT is established by traditional SPH models, it could undergo some numerical issues that strongly limit the applicability of the SPH method. One of the most striking issues is the over-attenuation of wave energy. The wave energy attenuation, behaving as the wave height decaying rapidly within a few wavelengths for progressive waves, has been a serious numerical issue that has to be faced by SPH practitioners when the SPH method is carried out for long-distance wave-propagation problems. The mechanism of such a phenomenon was investigated comprehensively by Colagrossi et al. [139] in 2013, where it was demonstrated that traditional WCSPH possesses the ability to accurately predict the attenuation process of viscous standing waves. However, to realize that it requires the number of neighbors per particle is sufficiently large, and this number should be gradually increased to achieve convergence towards theoretical solutions. In addition, it was also suggested that a higher number of neighbors is required for a larger Reynolds number. Notwithstanding, in practical applications, the number of neighbors per particle cannot be increased as desired because of the unbearable boosting computational costs.

Fortunately, this issue has been successfully resolved by Zago et al. [140] in 2021. In that work, an improved Kernel Gradient Correction (KGC) was imposed to the momentum equation to handle the dissipation issue. Compared with those traditional schemes (see, e.g., [109,141,142,143]), the improved KGC overcomes the non-reciprocity of inter-particle interactions by a symmetrized correction that guarantees the momentum conservation. As demonstrated by Zago et al. [140], the improved KGC shows excellent performance to prevent the wave attenuation with bearable computational costs. This work is a breakthrough corresponding to the industrial SPH applications towards realistic coastal and ocean engineering because it significantly makes the long-term and long-distance water waves simulations realizable.

3.2. Current and Wind Tunnels

In addition to the wave-generation and absorption techniques discussed above, it is also significant to build accurate and robust current and wind tunnels within the SPH framework to simulate the hydrodynamic performance of TCTs and FWTs, for which the working turbines are always fully immersed in the air (i.e., FWTs) or water (i.e., TCTs), respectively. However, because the SPH method is a purely Lagrangian meshless method, it is not trivial to model the inlet/outlet boundary conditions that are very straightforward to be implemented in mesh-based solvers. The main reason is that it is imperative to maintain the flow consistency by avoiding that all the fluid particles move out of the flow domain during simulations. To this end, various inlet/outlet boundary techniques have been proposed during the past two decades. The pioneering work related to the velocity inlet/outlet boundary conditions was conducted by Lastiwka et al. [144] and was further extended by other SPH practitioners (see, e.g., [145,146,147]). Generally, the fundamental principles of these approaches share the same characteristics with some special modifications depending on specific problems.

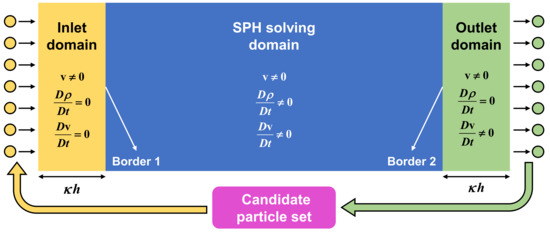

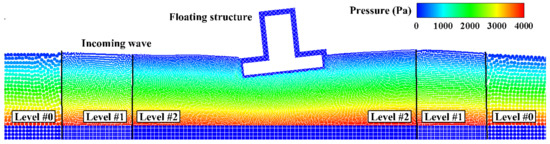

In order to clearly state the generic mechanism of the inlet/outlet boundary conditions, herein one of the most popular versions presented by Federico et al. [145] is illustrated. Figure 8 shows the bird view of a typical current/wind tunnel. One can see that the flow domain is divided into three parts prior to the simulation. At the inlet domain, the anticipated field quantities such as velocity and pressure are compulsorily assigned to the inlet particles. During time integration, these particles update their physical positions according to the time integration of velocity and do not participate in the SPH calculation. When the inlet particles are beyond the limit of the inlet domain (i.e., Border 1), they immediately become common SPH particles and then participate in the SPH calculation at the following time steps. Conversely, when the SPH particles run out of the limit of the SPH domain (i.e., Border 2), they will be immediately converted into the outlet particles and thereby free again from the SPH calculation. Finally, when a particle runs out of the outlet domain, it will be removed from the computational domain and then supplied into the candidate particle set that will be reused for creating inlet particles.

Figure 8.

The schematic diagram of inlet/outlet boundary conditions implemented in particle-based methods (e.g., SPH).

3.3. Numerical Issues Existing in NFTs

The same as other CFD tools, the SPH method has also been bothered by several numerical issues that could strongly limit its versatile applicability for different engineering problems. Among them, the most serious issues are the anisotropic particle distribution and tensile instability. The former could significantly reduce the particle consistency and thus the accuracy and stability of SPH simulations (see, e.g., [78]), while the latter could lead to numerical voids in those fluid domains characterized by strong negative pressures. In fact, these two numerical issues are inherent deficiencies regarding the SPH method. This section aims at providing the latest advanced SPH techniques to cope with them; these techniques are imperative to build an accurate, robust, and versatile NFT for simulating OEDs.

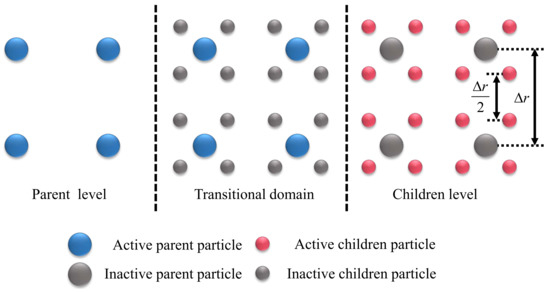

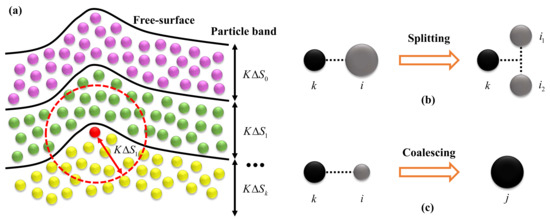

3.3.1. Disordered Particle Distribution: Using Particle-Shifting Techniques

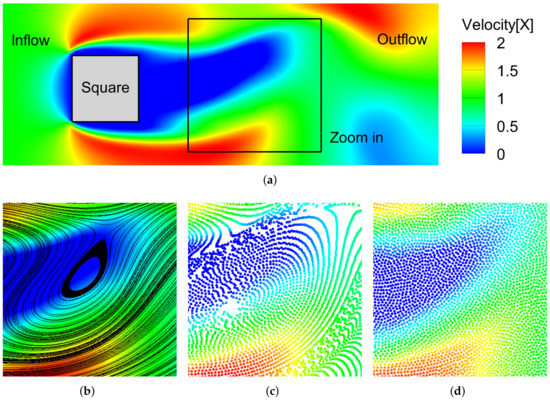

As a purely Lagrangian meshless method, traditional SPH models undergo the particle Lagrangian structures [148] that are characterized by serious particle clustering and clumping. The root of the Lagrangian particle structures can be attributed to the fact that the volume of each particle is simply obtained via the relation of during the time integration, providing no information regarding their volume shapes. As a consequence, whatever the initial distribution of particles, their volume shapes could be strongly stretched or compressed during flow evolutions since each particle must move along with the streamline they belong to; this results in the anisotropic deformations of the volumes macroscopically behaving as the strongly disordered particle pattern (see Figure 9a–c). As pointed out by Liu et al. [78], the regularity of a particle distribution significantly affects the order of particle consistency and thus the numerical accuracy and stability (see also the discussions provided by Antuono et al. [149]). Fortunately, this issue has been successfully resolved by the numerical technique known as the Particle-Shifting Techniques (PSTs) [92,150], which compulsorily shifts fluid particles from their streamlines to a new position according to some principles and thereby offers a homogeneous particle pattern as desired (see Figure 9d). Regarding the shifting principles, the most popular version is to reposition fluid particles from high-concentration regions to low-concentration regions on the basis of Fick’s diffusion law, which therefore forms the Fickian-based PST, which was firstly proposed by Lind et al. in 2012 [92]. The main idea of Lind’s PST can be mathematically written as

where is a diffusion coefficient that determines the magnitude of the shifting, which should satisfy several stability conditions as pointed out by Lind et al. [92]. Note that as reported by Sun et al. [118], in the WCSPH framework, the value of should be determined with a weakly compressible consideration. represents the particle concentration and usually comes from the sum of the kernel function, i.e.

Figure 9.

A uniform incoming flow crossing a square. The numerical results of panel (a,b) are obtained using an FV solver, while that of panel (c,d) are simulated via an SPH solver without and with PST, respectively. (a) FV result of the velocity field in the x-axis direction (Unit: m/s). (b) Streamlines via an FV solver. (c) SPH result without PST. (d) SPH result with PST.

After this pioneering work, PST has been further developed by the SPH community and applied to diverse problems, forming various PST variants in both the weakly compressible and truly incompressible senses (see e.g., [93,118,148,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159]). It is undeniable that PSTs can offer uniform particle distribution (i.e., better quality of particle distribution—see also Figure 10) and thus improve the numerical accuracy and stability of SPH simulations. Notwithstanding, it should be underlined that although the original version of PST and its variants show remarkable ability to cope with several challenging problems, their physical rationality could pose some limitations when being applied to realistic engineering problems. For instance, as reported by the extensive SPH literature (see, e.g., [155,157,158,160]), several versions of PST (see, e.g., [118,156]) could trigger the volume-non-conservation issue in simulating violent free-surface flows with long-term duration. This is caused by the fact that in these PST variants, after being repositioned, the particle positions are still updated according to an unchanged velocity field (i.e., non-Lagrangian transport velocity), which is nonphysical from a rigorous point of view. As a consequence, the accumulating errors on the potential energy gradually lead to the over-expansion (or over-compression when being subjected to negative pressures) of total fluid volume during simulations.

Figure 10.

The quality of particle distribution with (top panel) and without (bottom panel) PST. is closer to zero when the particle distribution is more uniform. For more details regarding the simulation configurations, the readers can refer to [119].

Therefore, the SPH community have been struggling for making PST more physical in different ways, such as integrating the shifting velocity, , into the governing equations (see, e.g., [155,158]) and using a fully Arbitrary-Lagrangian-Eulerian (ALE) framework (see, e.g., [148,161]); these variants strongly improve the rationality and interpretability of PSTs through rigorous mathematical considerations, although they require modifying the existing codes to a large extent because of the more complex formalism of the governing equations. In addition to that, there have been simpler measures such as locally deactivating shifting when the fluid suffers from the volume-non-conservation issue [157] or introducing a corrective cohesion force to adaptively compensate the over-expansion/compression [160]. On the whole, as a simple and powerful SPH technique, PSTs should be taken into account for simulating OEDs to improve the accuracy and stability of the simulation. Notwithstanding, which version of PSTs is the best choice for the concerning topic remains an open topic that needs to be further investigated in the future.

It should be underlined here that in addition to adopting PST, another effective measure to improve the numerical accuracy and robustness of SPH simulations is to implement high-order corrected scheme (see, e.g., [109,141,142,143,162,163]), which is a conventional method in the SPH community and can apparently recover the particle consistency in the case with anisotropic particle pattern (even kernel truncation) [78]. For more discussions corresponding to this topic, the readers can refer to [78,82].

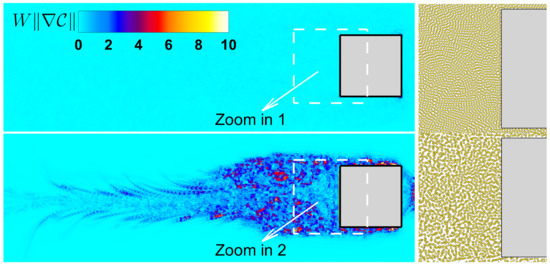

3.3.2. SPH Techniques to Prevent Tensile Instability

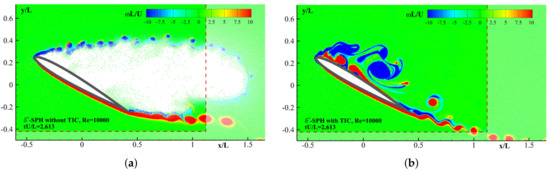

It is well known that when a body is subjected to current or wind excitations, the flow field past the body could be characterized by negative pressures induced by the continuous vortex shedding from the edge of the body. A typical example is flows passing a hydrofoil, which is very common when simulating the hydrodynamic performance of the blades installed on FWTs and TCTs. In this circumstance, vortex structures would be continuously discharged from the leading edge of the hydrofoil. This phenomenon can be excellently simulated using mesh methods that are inherently suitable for coping with such problems. However, in the context of SPH, the Tensile Instability (TI) is one of the most critical numerical issues that could destroy the SPH simulation in total when negative pressures are involved. Macroscopically, when TI occurs, the SPH particles could clump/cluster together and thereby trigger spurious flow voids in the flow field. On the contrary, from the microscopical point of view, as pointed out very recently by Lyu et al. [119], the occurrence of TI is indeed caused by the errors of the particle approximation of the kernel gradient. In other words, TI is an inherent deficiency of SPH, and it cannot be removed even by refining particle resolution (see [119] for more details). Therefore, special techniques are needed to tackle the issue. At present, the most effective method to deal with TI is the technique named Tensile Instability Control (TIC) proposed by Sun et al. in 2018 [164]. The principle of TIC can be expressed as

where denotes the free-surface particles. The subscripts i and j refer to the targeted particle and its neighboring particle within the support radius, respectively. As demonstrated by Sun et al. [164], the incorporation with TIC can cope with several challenging problems (see, e.g., Figure 11) that are almost impossible to be successfully simulated using traditional SPH models (see, e.g., [164,165]).

Figure 11.

Direct SPH simulation of viscous flow around a foil at Re = 10,000 without (a) and with (b) TIC. The flow void is induced when TIC is not used. For more details regarding the simulation configurations, the readers can refer to [164].

It is worth noting that in addition to TIC, another effective measure is to add a background pressure (BP) for the whole computational domain; this measure is very popular in the early years because of its easy-to-realize and effective properties. Nevertheless, this measure cannot be directly implemented to those problems where a free-surface exists since in the WCSPH context DFSBC is implicitly fulfilled [103]. In fact, several SPH practitioners have attempted to extend the BP technique to free-surface problems (see, e.g., [166]), whereas it has been proved that TIC possesses better accuracy and stability than the BP technique, at least for the hydrodynamic loads acting on body surfaces [119]. In the context of simulating OEDs, the phenomena involving negative pressures are very common (e.g., vortex shedding for hydrofoils and VIV and VIM problems), and therefore TIC should be employed to prevent the numerical fluid voids that drastically reduce the accuracy and stability of SPH simulations.

4. Multibody Coupling and Mooring Hydrodynamics

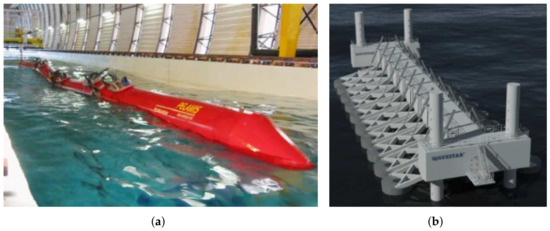

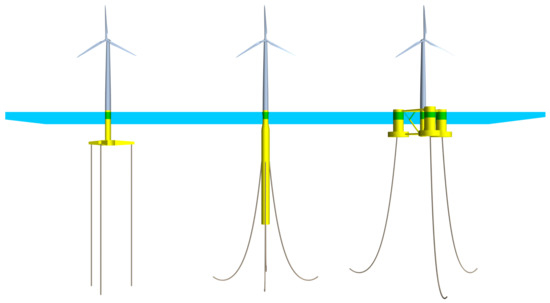

Because most of OEDs exploit ocean energy via transmitting mechanical energy into PTO systems, joints/sliders (hereafter referred to as Mechanical Constraint Structures, MCSs) are very common and important in such a process for energy transmission. MCSs can provide kinematic constraints between several objects, allowing that the transmission system of OEDs can more flexibly transmit the mechanical energy of fluids into electricity. For instance, Figure 12a shows the famous attenuator-type WEC named Pelamis [47,167], which consists of four tubular sections connected by three hinged modules that can move relatively to each other. Figure 12b displays another attenuator-type WEC called WaveStar [168], which absorbs wave energy through several partially submerged buoys installed on either longitudinal side of the device. In addition, various OEDs such as FWTs always consist of a main-body module and a mooring system to stabilize the device motion just as those conventional vessels and platforms. Figure 13 illustrates different mooring systems of several types of FWTs, from left to right being the TLP type, the Spar type, and the semi-submersible type, respectively. From the above-shown figures, it is clear that the multibody coupling and mooring dynamics are very important for evaluating the power-generation ability of OEDs. In the early years, although extensive efforts have been devoted to investigating different types of OEDs such as position-fixed WECs (see, e.g., [169,170]) or moving/floating WECs (see, e.g., [171,172,173]), these investigations were conducted without the multibody and mooring dynamics considerations. The SPH community has been pursuing feasible and user-friendly solutions to cope with such complex problems.

Figure 12.

Typical articulated systems installed on different WECs. (a) Pelamis WEC [47]. (b) WaveStar WEC [168].

Figure 13.

Typical mooring systems installed on different FWTs with TLP type (left), Spar type (middle), and semi-submersible type (right).

Historically, several popular commercial solvers based on the BE approach such as ANSYS AQWA and DNV SESAM have already provided corresponding modules (including both MCSs and mooring solvers) to tackle such problems. Nevertheless, as discussed in Section 1, these packages are incapable of capturing the nonlinearity behaviors of free-surface evolutions and are hard to be integrated into the SPH solver due to their closed-source property (for more details regarding the BE applications in simulating OEDs, the readers can refer to [174]). On the other hand, extensive efforts have been devoted to coupling FSI solvers with mooring dynamics solvers through different strategies. For instance, the open-source solver MoorDyn has been coupled with the WEC-Sim package (an open-source BE solver based on Matlab) as its mooring module [175]. Another typical example is the OpenFoam solver, which has been further developed by several researchers by integrating in-house mooring modules for the simulations of several traditional ocean engineering structures (see, e.g., [176,177,178,179]), and OEDs such as FWTs as well (see, e.g., [180,181]). However, to the best knowledge of the authors, these existing open-source solvers still lack the ability to cope with an arbitrary number of jointed objects.

At present, the SPH community has been also struggling for developing an “FSI + MCSs + Mooring” coupling solver through different strategies, among which two breakthroughs, as shown in Table 1, have been achieved by DualSPHysics developers and SPHinXsys developers via “DualSPHysics + Project Chrono + MoorDyn” and “SPHinXsys + Simbody” strategies, respectively. Considering their easy accessibility, user-friendly pipeline, good balance between accuracy and efficiency, and more importantly, high feasibility towards simulating OEDs, in this section only these two combinations are involved.

Table 1.

A comparison of the coupling strategies adopted by DualSPHysics and SPHinXsys.

4.1. DualSPHysics’ Solution: Incorporating with Project Chrono and MoorDyn

DualSPHysics is an open-source package devoted to solving the Navier–Stokes equation based on WCSPH, which was initially released in 2011 with the purpose of coping with coastal engineering problems [107]. Thanks to its accuracy and robustness characteristics, DualSPHysics has been significantly improved towards more complicated multi-physics problems by the SPH practitioners and its developers during the past decade (for more details regarding the latest developments of DualSPHysics, the readers can refer to [120]). As pointed out by its developers, the successful coupling with other solvers has been a milestone in the development of DualSPHysics [120]. Among them, the combination of “DualSPHysics + Project Chrono + MoorDyn” is the most significant achievement, which makes DualSPHysics the most powerful toolkit at present for simulating OEDs with articulated and moored structures.

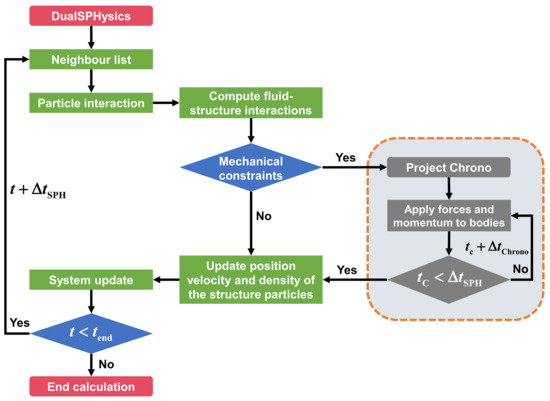

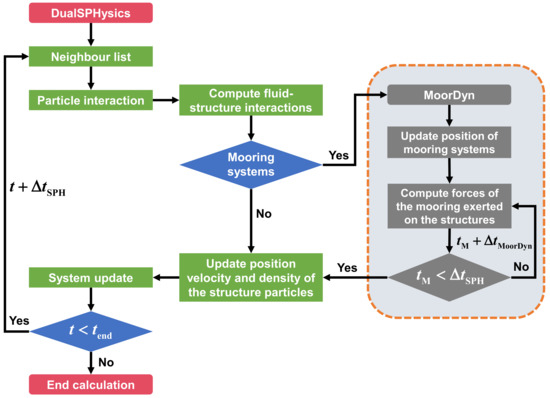

Project Chrono is an open-source multi-physics platform with excellent abilities to simulate collisions and mechanical restrictions such as sliders, springs, and hinges. One of the most striking superiorities of Project Chrono is that this solver can be coupled with DualSPHysics within a unified meshfree framework to cope with complex articulated systems. The flow chart of the coupling process between DualSPHysics and Project Chrono is illustrated in Figure 14. Regarding the mooring dynamics, in fact, several efforts have been dedicated to this topic within the DualSPHysics framework. For instance, inspired by the quasi-static approach proposed by Faltinsen [60], in 2016, Barreiro et al. [185] modeled the mooring system via continuous ropes and wires described by the catenary function. This method was also adopted to simulate floating OWCs moored to the seabed by Crespo et al. in 2017 [186]. However, in that model, only the tension of the mooring lines can be properly solved with the hydrodynamics and the inertial and axial elasticity of the mooring lines being neglected. Fortunately, in 2019, the MoorDyn solver has been successfully coupled with DualSPHysics by Domínguez et al. [187], significantly improving the abilities of DualSPHysics towards simulating moored structures. Since then, this strategy has been widely applied to various mooring systems such as floating breakwaters and WECs (see, e.g., [188,189]). The flow chart of the coupling process between DualSPHysics and MoorDyn is illustrated in Figure 15.

Figure 14.

The flow chart of the coupling process between DualSPHysics and Project Chrono (adapted from [120]).

Figure 15.

The flow chart of the coupling process between DualSPHysics and MoorDyn (adapted from [120]).

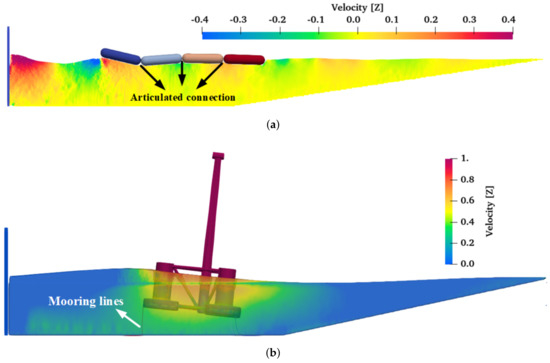

Typical simulation results of DualSPHysics’ multi-solvers coupling strategy are illustrated in Figure 16. In Figure 16a, the snapshot of a working Pelamis WEC solved by “DualSPHysics + Project Chrono” strategy is shown. The PTO system of Pelamis consists of several hinged cylinders connected to each other, which involves complex relative motion of different parts during working and thus needs a multibody dynamics solver to cope with. In Figure 16b, a mooring semi-submersible FWT under regular wave excitations is displayed, which is simulated through a “DualSPHysics + MoorDyn” strategy. Of course, DualSPHysics can also be employed to investigate other types of OEDs such as point absorbers (see, e.g., [190,191,192]) and OWSCs (see, e.g., [193]). From these discussions, it is clear that the latest version of DualSPHysics (i.e., v5.0) has become a reliable and powerful toolkit for simulating OEDs. It is worth noting that because DualSPHysics is an open-source platform, it can be efficiently coupled with other solvers. For instance, Cui et al. [194] have successfully coupled DualSPHysics with another open-source mooring solver Mooring Analysis Program (MAP++) provided by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). This coupling solver has been applied to investigate the hydrodynamic performance of a new-type breakwater, and good numerical results were obtained compared with experimental data.

Figure 16.

Typical simulation results of the coupling strategy of DualSPHysics [120]. (a) Pelamis by “DualSPHysics + Project Chrono.” (b) Semi-submersible FWT by “DualSPHysics + MoorDyn.”

4.2. SPHinXsys’ Solution: Incorporating with Simbody

In addition to DualSPHysics, another alternative SPH toolkit to simulate OEDs is SPHinXsys coupling with Simbody. Differing from DualSPHysics that aims at simulating coastal engineering problems, SPHinXsys has been initially developed for the sake of providing a generic C++ Application Programming Interface (API) with high flexibility for domain-specific problems, including fluid dynamics [135], solid mechanics [195], electromechanics, thermodynamics, and reaction–diffusion flows [112]. SPHinXsys is also capable of simulating multibody dynamics problems via incorporating with Simbody. Simbody, firstly released by Stanford University, is an open-source multibody mechanics library towards mechanical, neuromuscular, prosthetic, and biomolecular simulations, which has been intended as a free-access package that can be employed to incorporate robust, high-efficiency multibody dynamics into a broad range of domain-specific end-user applications [184]. Figure 17 displays the snapshot of a seabed-mounted bottom-hinged OWSC subjected to regular wave excitations, which has been recently investigated and reported by Zhang et al. [135] using the “SPHinXsys + Simbody” strategy. Despite this, a mooring-dynamics module has not been officially provided by the solver’s developers, while this can be efficiently realized by users, just as what was done by DualSPHysics’ developers, through incorporating with any open-source mooring dynamics solvers such as MoorDyn and MAP++.

Figure 17.

The snapshot of a working OWSC solved by the “SPHinXsys + Simbody” strategy. Note that this snapshot is adapted from [135] with its author’s kind permission.

It is worth noting that owing to the merits of the Object Oriented Programming (OOP) property, the aforementioned open-source solvers (i.e., Project Chrono, Simbody, and MoorDyn) can be coupled easily with either other open-source SPH solvers or SPH practitioners’ in-house solvers. For example, Wei et al. [196] have successfully coupled the open-source SPH solver GPUSPH with Project Chrono to simulate the hydrodynamic performance of an OWSC. Nevertheless, the strategies provided by DualSPHysics’ and SPHinXsys’ developers are still strongly recommended because of their freely accessible properties; at least, these two solutions are now the most user-friendly resolutions to cope with such problems for those engineers who want to be an SPH user rather than an SPH developer.

5. Hydroelastic Effects in Hydrodynamic Problems Related to OEDs

5.1. The Origin of the Flexibility of OEDs

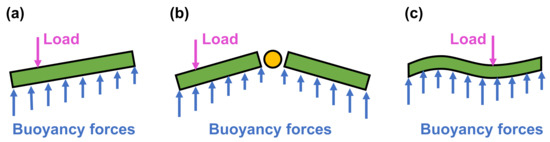

As for those small-scale OEDs, the hydroelasticity is negligible, whereas it plays an important role when considering the FSI process for a large-scale structure such as IEHSs that has become more and more popular in recent years (see, e.g., [5]). The typical characteristic length of IEHSs could be up to a few hundred meters, or even kilometers, while conventional platforms are usually below ~150 m. In this circumstance, the flexibility of the system cannot be neglected. Generally speaking, the flexibility of IEHSs appears in two forms: (1) the flexibility of the connector components between different system modules (see, e.g., [27] and Figure 18b) and (2) elastic deformations of the whole system (see, e.g., [27] and Figure 18c). In terms of the former, more precisely speaking, when an IEHS is linked by flexible connectors, the whole system cannot be regarded as a rigid body just as a traditional vessel/platform (see Figure 18a) because there are relative motions between different parts of the system (see Figure 18b). In fact, such a type of flexibility is always referred to as multibody dynamics, for which the readers can refer to Section 4 for more details; this section will focus on another type of flexibility, i.e., hydroelasticity (see Figure 18c).

Figure 18.

Typical structure responses of ocean engineering structures with rigid body (a), connected body (b), and flexible body (c) (adapted from [6]). Panels (b,c) represent the flexible deformations caused by the connectors and the structures themselves, respectively.

Hydroelasticity, one of the most challenging topics in ocean engineering, has attracted long-lasting attention from both the scientific and industrial communities. In fact, in the early years, little attention was paid to hydroelasticity because, at that time, the characteristic length of almost all ocean engineering structures was below ~150 m. Nevertheless, as the increasing demands of human activities, Very Large Floating Structures (VLFSs) appeared, such as floating runways, floating cities, and of course IEHSs as well (see, e.g., [197,198]). In this circumstance, the elastic deformations of IEHSs must be taken into account when the characteristic length of the IEHSs exceeds the wavelength [198]. On the other hand, in the last decade, there has been growing attention towards flexible-body WECs enabled by rubber-like elastomeric composite membrane materials [199], which also introduces elasticity into the system. Therefore, an SPH solver handling the hydroelastic FSI processes has been required to meet such demands. Recently, Gotoh et al. [77] have offered a comprehensive review for the latest development of different types of a particle-based hydroelastic FSI solver in ocean engineering; the readers can refer to that work for more details. Differing from that study, this section is not to provide the advancements of hydroelastic FSI solver within the SPH framework but to highlight the most challenging problems in modeling the hydroelastic interactions regarding OEDs.

5.2. Coupling Methods between SPH and Other Structure Solvers

In the context of SPH, two mature coupling paradigms are widely adopted to simulate the hydroelastic interactions. One typical method is to use the particle-mesh coupling strategy where the SPH solver is usually adopted for the fluid portion, while the mesh solver is adopted for the structure portion. Regarding this coupling measure, extensive works can be found in the literature, such as SPH-FE (Finite Element) (see, e.g., [200,201,202,203,204]), the Smoothed Point Interpolation Method (SPH-SPIM) (see, e.g., [205,206]), and MPS-FE (see, e.g., [76,207,208,209]). Another method is totally based on Lagrangian particles either for the fluid solver or the structure solver, e.g., SPH-TLSPH (Total Lagrangian SPH) (see, e.g., [210,211,212,213,214]), the Reproducing Kernel Particle Method (SPH-RKPM) (see e.g., [215,216]), and SPH-PD (Peridynamics) (see, e.g., [217,218,219,220]). In the context of simulating OEDs, which coupling paradigm is the best choice for realistic engineering applications is still an open topic that needs to be further investigated by the SPH community. As pointed out by Gotoh et al. [77], an entirely Lagrangian meshfree framework would bring about several distinct superiorities including higher flexibility, extendibility, generality, and reliability. Despite these, it should be highlighted here that for the realistic engineering problems regarding OEDs that usually involve complex 3D structures (both for external surface and internal skeleton), generating body-fitted and uniformly distributed particles for that is quite challenging even using the particle generator provided by SPHinXsys. On the contrary, there have been various mature grid generators, e.g., ANSYS ICEM, Dassault ABAQUS, and Altair Hypermesh, that can be directly employed to create a set of high-quality body-fitted grids even for very complex 3D structures. From this point of view, in the context of simulating OEDs towards realistic engineering problems, the particle-mesh coupling strategy seems a competitive method to cope with such problems. Notwithstanding, because of the inherent discrepancies of the particle method and the mesh method, how to accurately exchange field information between the fluid–structure interface is a quite challenging problem; this drastically affects the accuracy and stability of a particle-mesh coupling solver, whereas the entirely Lagrangian particle method is free from this issue because both the fluid and structure portions can be solved in a unified framework.

Unfortunately, in the majority of the existing literature, each coupling strategy have been only applied to simple benchmarks, for instance, dam-breaking flows impacting on an elastic plate (see, e.g., [195,210,211,214,221]), sloshing flows bending an elastic baffle (see, e.g., [214,222,223,224]) and the water entry problem for an elastic wedge (see, e.g., [222,223,225,226]). Little attention has been focused on realistic engineering applications for complex 3D structures. Besides, as mentioned above, IEHSs are not only featured by elastic deformations but also by the coupled multibody dynamics between different floating modules; in this sense, a “hydroelasticity-multibody” coupling FSI solver is required for such problems. On the whole, these remain challenging topics needed to be overcome by the SPH community in the future.

6. Multiphase Effects in Hydrodynamic Problems Related to OEDs

Multiphase flows are common phenomena that widely exist in various engineering problems. Different from other industries such as chemistry, and manufacturing where multi-component fluids exist (always more than three components), for most cases regarding ocean engineering, the multiphase problems only involve air and water, which are also the most common fluid media in the OEDs scenario. Note that cavitating flows are not considered herein because there is no mature SPH model of cavitation until now, although this phenomenon has been considerably investigated by mesh-based solvers (see, e.g., [227,228,229,230]). It should be underlined here that this section is not to provide a comprehensive review of the last development of multiphase SPH models but to discuss those multiphase problems regarding OEDs and the existing efforts provided by the SPH community.

In fact, compared with the interface-tracking techniques needed in Eulerian mesh-based solvers (see, e.g., [231,232,233]), multiphase simulations can be more straightforwardly realized in the SPH context, but some numerical issues should be tackled. The most striking one is the density discontinuity at the air–water interface. Colagrossi and Landrini [86] made the pioneering work for simulating air–water multiphase flows at realistic density ratios by rewriting the differential operators of gradient and divergence to minimize the errors caused by the significant density gradient at the interface. After that, several advancements have been made by the SPH community in these years (see, e.g., [234,235,236,237,238,239]). Despite these successes, in the context of simulating OEDs, several issues deserve our attention and will be discussed in the following.

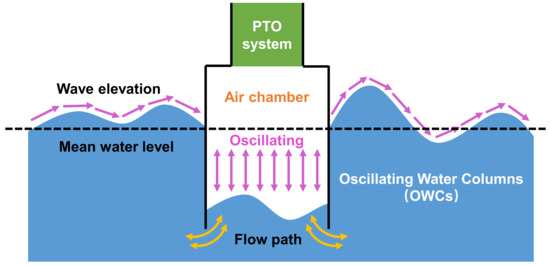

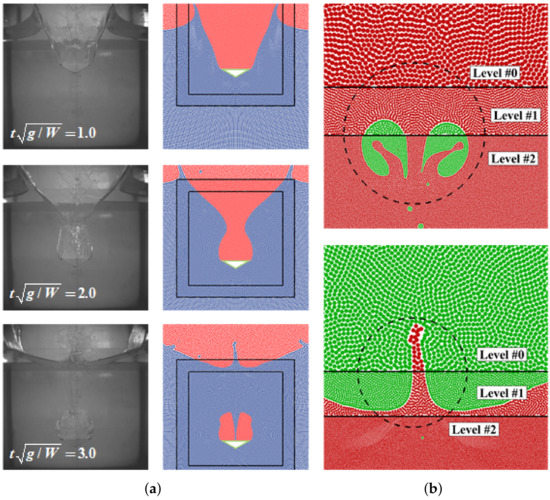

6.1. Multiphase Effects in the OWCs

One typical example corresponding to OEDs for multiphase flows is the Oscillating Water Columns (OWCs). As shown in Figure 19, the main idea of an OWC is to drive an air turbine by exploiting the oscillating air pressures from a periodically moving water level. When a single-phase SPH model is applied to simulate such a problem, some numerical techniques are required to reduce the errors caused by the ignorance of pneumatic effects. One widely adopted method is to make the top of the OWC opening, which means that the pressure of the pneumatic parts is equal to the atmospheric pressure (see, e.g., [240]). As pointed out by Crespo et al. [186], this method makes the pneumatic effects of the problem negligible. Of course, the air chamber can be also closed when the total height of the air chamber is greatly higher than the internal water level (see, e.g., [169]). Another feasible and more accurate approach, as reported by Quartier et al. [241], is to place a cover floating on the top of the water level inside the OWC chamber, which can numerically replace the PTO system by implementing appropriate external forces on the cover (i.e., enforcing artificial damping to the flow system). The results indicate that considering the “air effects” possesses better accuracy than using single-phase SPH models as implemented in [169,186]. Nevertheless, it should be highlighted that the “air-effects” considered by Quartier et al. [241] is only a simplified model because the air pressures inside the OWC chamber are obtained by theoretical formulas, and then it was converted just like equivalent damping to the floating cover. Therefore, such a simplification is only a compromise to achieve a balance between numerical accuracy and efficiency, which is, however, hard to accurately reproduce the real working conditions of the whole OWC, especially for the flow information of the air chamber. Hence, a multiphase SPH model is needed when conducting a comprehensive simulation of OWCs.

Figure 19.

The schematic diagram of a well-type OWC.

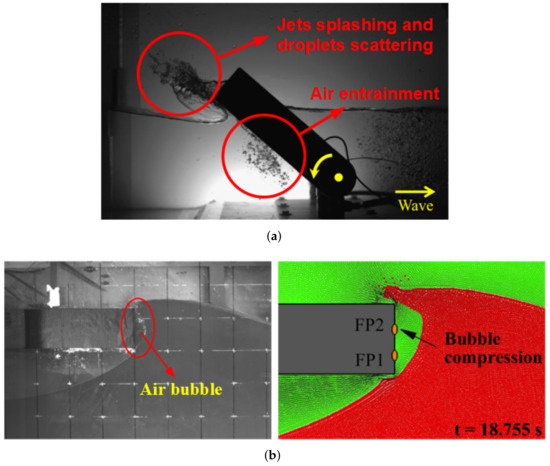

6.2. Air-Cushioning Effects in the Wave Slamming on OEDs

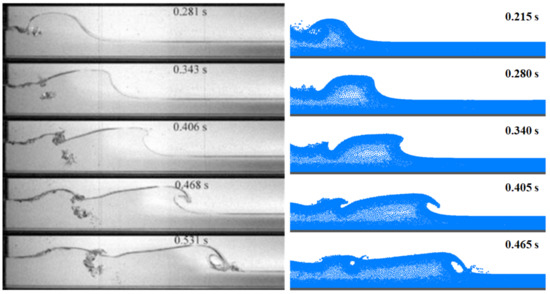

In addition to that, another significant phenomenon associated with multiphase effects is the air-cushioning/entrainment effects, which usually occur during a slamming process. Slamming, characterized by strong nonlinear interactions between fluid and structure, has been considerably investigated for a long time because of its tight relevance to the hydrodynamics of vessels, platforms, and OEDs as well. In terms of OEDs, it is worth noting that these devices, especially for WECs, usually work in harsh sea environments because it facilitates their abilities to energy harvesting. In other words, WECs are in favor of possessing the largest motion responses possible to generate electricity, which is quite different from conventional offshore structures that always require small motion responses in different working conditions. Therefore, from this point of view, slamming could play a more relevant role in the hydrodynamic performance of WECs than other types of ocean engineering structures.