The Trait of Extraversion as an Energy-Based Determinant of Entrepreneur’s Success—The Case of Poland

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Through the prism of labor economy and the phenomena accompanying taking up a specific type of employment (I);

- Microeconomic theories of innovation (II);

- Macroeconomic theories of innovation, growth and economic cycles (III).

- Extroverts draw energy from social interactions and are seen as outgoing and friendly [24].

- Conscientiousness is characterized by a tendency to be punctual, well-organized, diligent and thorough [30].

- Neuroticism, or low emotional stability, refers to the tendency to experience negative emotions and the behaviors that accompany them [24]. Highly neurotic individuals tend to be stressed, anxious, impulsive and vulnerable [31], and as a result exhibit ineffective coping strategies and poor emotional adjustment strategies [24,32].

2. Materials and Methods

- Age over 30 (the basic assumption in the Big Five model—the need to stabilize the hormonal balance of the human body).

- Self-employment (entrepreneur).

- Uninterrupted period of running one’s own business for a minimum of 20 years (this parameter is particularly important because the period of the last 20 years has been accompanied by structural changes in running a business: transformation of the socialist economy into a free market economy and accession to the European Union)

- Building an organization from scratch.

- Age (over 30—lower limit of the OCEAN model);

- Work experience (minimum 20 years);

- Belonging to the top management in the organization (director position or higher).

- Mean;

- Standard deviations;

- Minimum and maximum;

- Median and quartiles.

3. Results

3.1. Metrics

3.2. The BIG5 Model in the Test Results

- O—test group 67.4 and control group 73.0;

- C—test group 67.6 and control group 75.1;

- E—test group 67.6 and control group 54.1;

- A—test group 78.1 and control group 72.0;

- N—test group 34.6 and control group 42.7, which positively verifies H1.

- O—0.0021;

- C—0.0026;

- E—0.0001;

- A—0.0015;

- N—0.0261.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Big Five Personality Traits Test

| Rate Each Statement According to How Well It Describes You. Base Your Ratings on How You Really Are, Not How You Would Like to Be. | |||||

| Inaccurate | Neutral | Accurate | |||

| I have a kind word for everyone | |||||

| I am always prepared | |||||

| I feel comfortable around people | |||||

| I often feel blue | |||||

| I believe in the importance of art | |||||

| I feel I am better than other people | |||||

| I avoid taking on a lot of responsibility | |||||

| I make friends easily | |||||

| There are many things that I do not like about myself | |||||

| I am interested in the meaning of things | |||||

| I treat everyone with kindness and sympathy | |||||

| I get chores done right away | |||||

| I am skilled in handling social situations | |||||

| I am often troubled by negative thoughts | |||||

| I enjoy going to art museums | |||||

| I accept people the way they are | |||||

| It’s important to me that people are on time | |||||

| I am the life of the party | |||||

| My moods change easily | |||||

| I have a vivid imagination | |||||

| I take care of other people before taking care of myself | |||||

| I make plans and stick to them | |||||

| I do not like to draw attention to myself | |||||

| I often feel anxious about what could go wrong | |||||

| I enjoy hearing new ideas | |||||

| I start arguments just for the fun of it | |||||

| I always make good use of my time | |||||

| I have a lot to say | |||||

| I often worry that I am not good enough | |||||

| I am not interested in abstract ideas | |||||

| I criticize other people | |||||

| I find it difficult to get to work | |||||

| I stay in the background | |||||

| I seldom feel blue | |||||

| I do not like art | |||||

| I stop what I am doing to help other people | |||||

| I change my plans frequently | |||||

| I do not talk a lot | |||||

| I feel comfortable with myself | |||||

| I avoid philosophical discussions | |||||

| Rate each word according to how well it describes you. Base your ratings on how you really are, not how you would like to be. | |||||

| Inaccurate | Neutral | Accurate | |||

| Original | |||||

| Systematic | |||||

| Shy | |||||

| Soft-Hearted | |||||

| Tense | |||||

| Inquisitive | |||||

| Forgetful | |||||

| Reserved | |||||

| Agreeable | |||||

| Nervous | |||||

| Creative | |||||

| Self-Disciplined | |||||

| Outgoing | |||||

| Charitable | |||||

| Moody | |||||

| Imaginative | |||||

| Organized | |||||

| Talkative | |||||

| Humble | |||||

| Pessimistic | |||||

Appendix B. Entrepreneur’s Questionnaire

| Question | Answer | ||||

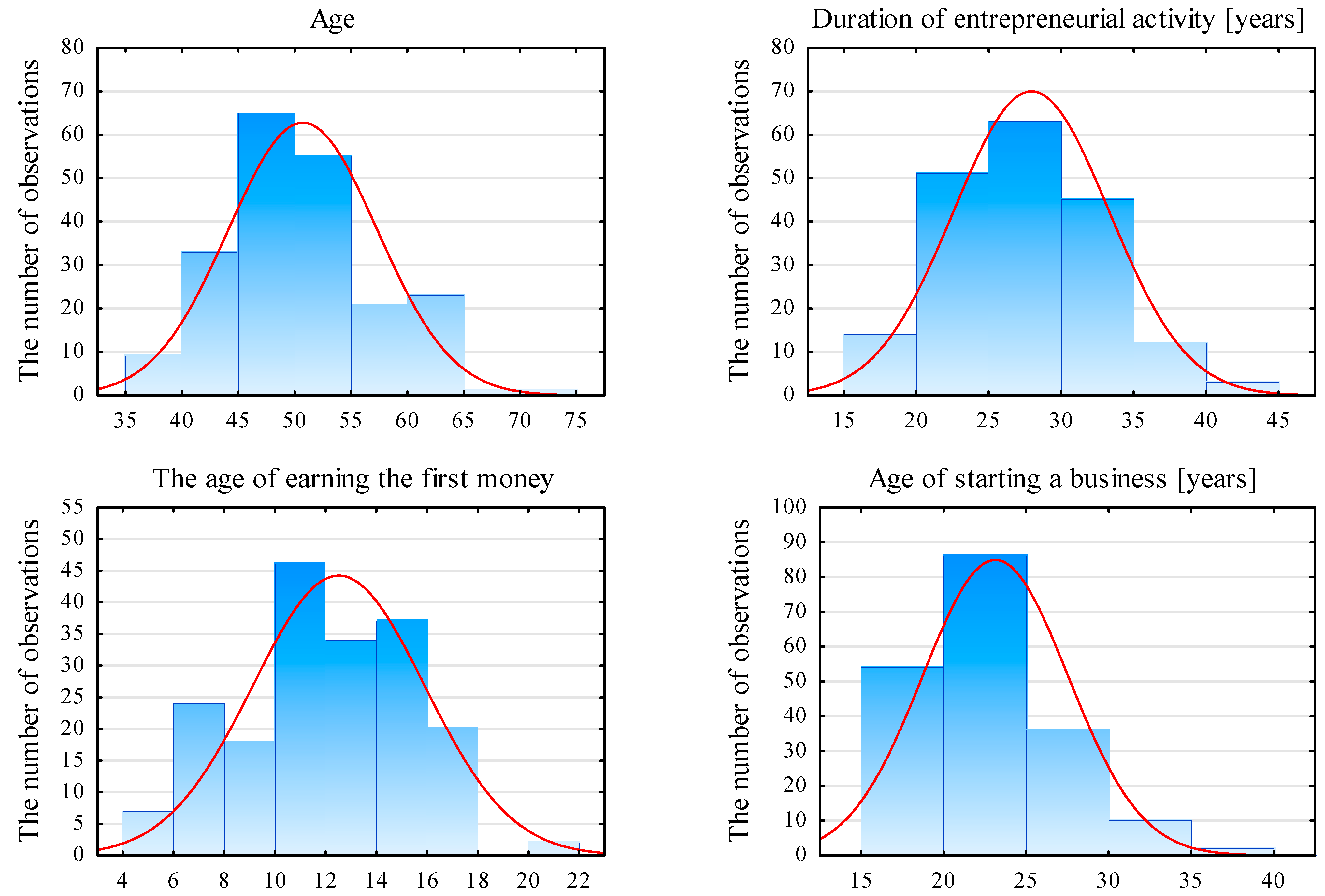

| 1. Present age? | |||||

| 2. The duration of doing business? | |||||

| 3. In what age did you earn the first money? | |||||

| 4. In what age did you earn the first money as an entrepreneur? | |||||

| 5. What were your motives to starting a business? | |||||

| 6. Did anybody support you with the entrepreneurial knowledge? If Yes—who? | |||||

| 7. What was the property status of your parents (in relation to the national average) in the moment of starting business? | Very poor | Poor | Average | Well | Very well |

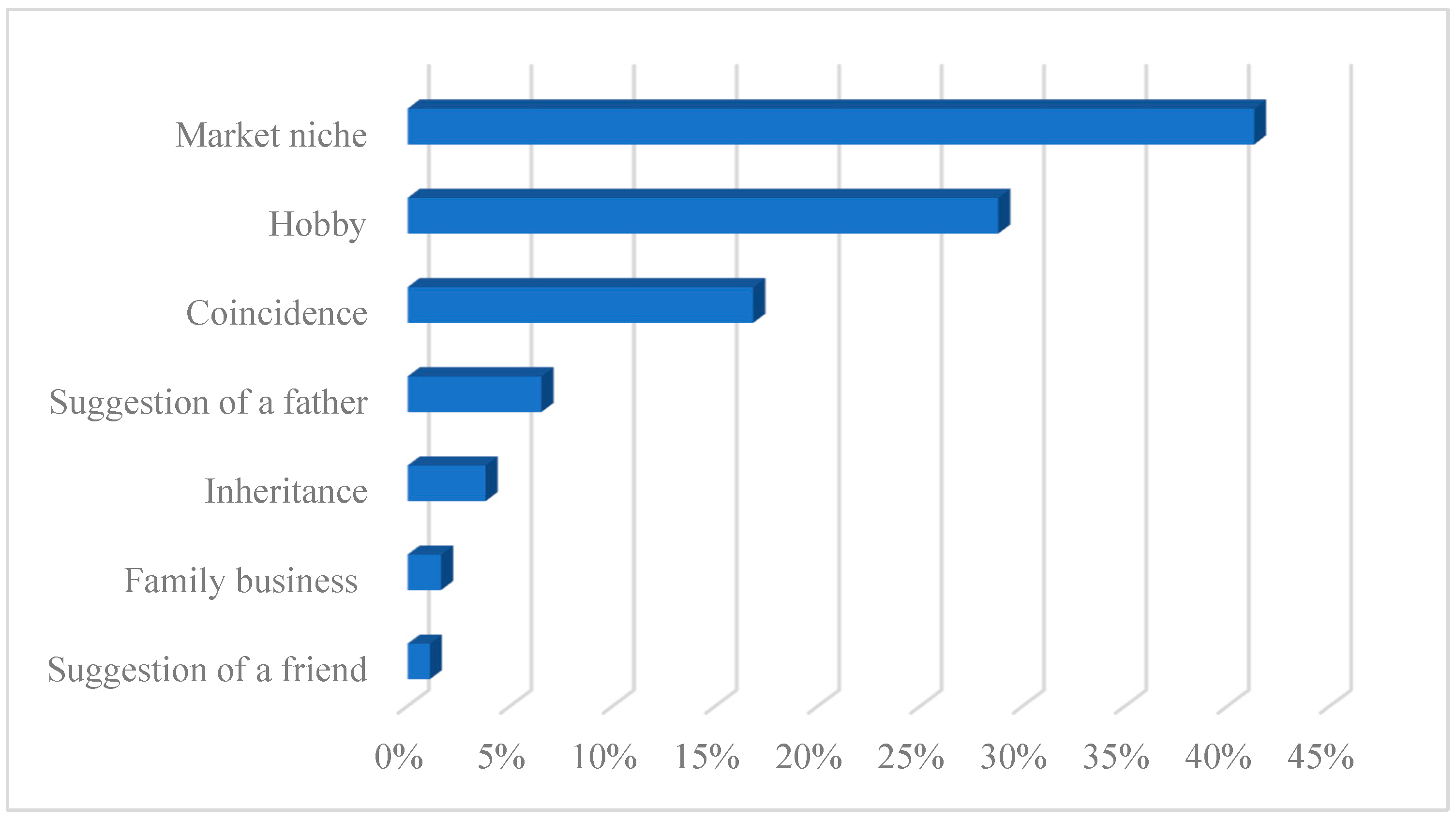

| 8. What was the source of the idea for running a business? | |||||

| 9. Is the business characteristics coherent with your education profile? | |||||

| 10. To what extent did the obtained (state) education provide knowledge that helped in doing business? | It hindered very badly | It hindered badly | It hindered moderately | Neither helped nor hindered | Helped moderately |

| Helped well | Helped very well | ||||

| 11. How did you perceive the risk level of starting business in that time? | None | Very low | Low | Neutral | Medium |

| High | Very high | ||||

References

- Zhang, D. Energy Finance: Background, Concept, and Recent Developments. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2018, 54, 1687–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Melnychenko, O. The Energy of Finance in Refining of Medical Surge Capacity. Energies 2021, 14, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korol, T. Evaluation of the Macro-and Micro-Economic Factors Affecting the Financial Energy of Households. Energies 2021, 14, 3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korol, T. Examining Statistical Methods in Forecasting Financial Energy of Households in Poland and Taiwan. Energies 2021, 14, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, J.; Bradshaw, D. Aristotle East and West: Metaphysics and the Division of Christendom. Sixt. Century J. 2007, 38, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Mises, L. Human Action: A Treatise on Economics; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Thorton, M. An Essay on Economic Theory; An English translation of Richard Cantillon’s Essai sur la Nature du Commerce en Général; Mises Institute: Auburn, AL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J.A. The Theory of Economic Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1912. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, F.H. Risk, Uncertainty and Profit; Houghton-Mifflin: New York, NY, USA, 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Carpini, J.A.; Parker, S.K.; Griffin, M.A. A look back and a leap forward: A review and synthesis of the individual work performance literature. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 825–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, J. Hayek’s Spiritual Science. Mod. Intellect. Hist. 2020, 19, 473–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirzner, I. Perception, Opportunity and Profit: Studies in the Theory of Entrepreneurship; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, B.W.; DelVecchio, W.F. The rank-order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: A quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 126, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B.W.; Jackson, J.J. Sociogenomic Personality Psychology. J. Personal. 2008, 76, 1523–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ashton, M.C.; Lee, K. Empirical, theoretical, and practical advantages of the HEXACO model of personality structure. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 11, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, I.B.; McCaulley, M.H.; Quenk, N.L.; Hammer, A.L. MBTI Manual: A Guide to the Development and Use of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, 3rd ed.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cattell, R.B.; Eber, H.W.; Tatsuoka, M.M. Handbook for the Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire (16 PF); Institute for Personality and Ability Testing: Champaign, IL, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- John, O.P.; Donahue, E.M.; Kentle, R.L. The Big Five Inventory-Versions 4a and 54; Institute of Personality and Social Research, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, O.P.; Naumann, L.P.; Soto, C.J. Paradigm shift to the integrative big five trait taxonomy. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 3, pp. 114–158. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, G.W.; Odbert, H.S. Trait-names: A psycho-lexical study. Psychol. Monogr. Gen. Appl. 1936, 47, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattell, R.B. The description of personality: Basic traits resolved into clusters. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1943, 38, 476–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T., Jr.; McCrae, R.R. Age differences in personality structure: A cluster analytic approach. J. Gerontol. 1976, 31, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, B.P.; Goldberg, L.R. Act-frequency signatures of the Big Five. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 116, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T., Jr.; McCrae, R.R.; Löckenhoff, C.E. Personality Across the Life Span. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 423–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T., Jr. Toward a New generation of personality theories, theoretical contexts of for The Five-factor model. In The Five-Factor Model of Personality: Theoretical Perspectives; Wiggins, J.S., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 51–87. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T., Jr.; Ostendorf, F.; Angleitner, A.; Hřebíčková, M.; Avia, M.D.; Sanz, J.; Sánchez-Bernardos, M.L.; Kusdil, M.E.; Woodfield, R.; et al. Nature over nurture: Temperament, personality, and life span development. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 78, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T., Jr. Understanding persons: From Stern’s personalistics to Five-Factor Theory. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 169, 109816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, O.F. Higher-order factors of personality in self-report data: Self-esteem really matters. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 53, 568–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, R. Personality, Values, Culture: An Evolutionary Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Oh, I.-S.; Colbert, A.E. Understanding organizational commitment: A meta-analytic examination of the roles of the five-factor model of personality and culture. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 1542–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinangil, H.K.; Viswesvaran, C.; Ones, D.S.; Anderson, N. Organizational perspectives: Organizational psychology. In Handbook of Industrial, Work and Organizational Psychology; Anderson, N., Ones, D.S., Sinangil, H.K., Viswesvaran, C., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; Volume 2, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Zapata, C.P. The person–situation debate revisited: Effect of situation strength and trait activation on the validity of the big five personality traits in predicting job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 58, 1149–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Digman, J.M. Personality structure: Emergence of the five-factor model. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1990, 41, 417–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; John, O.P. An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. J. Personal. 1992, 60, 175–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briley, D.A.; Tucker-Drob, E.M. Genetic and environmental continuity in personality development: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 1303–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraley, R.C.; Roisman, G.I.; Booth-LaForce, C.; Owen, M.T.; Holland, A.S. Interpersonal and genetic origins of adult attachment styles: A longitudinal study from infancy to early adulthood. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 104, 817–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Campbell, J.P. Modeling the performance prediction problem in industrial and organizational psychology. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 2nd ed.; Dunnette, M.D., Hough, L.M., Eds.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1990; Volume 1, pp. 687–732. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.P.; McCloy, R.A.; Oppler, S.H.; Sager, C.E. A theory of performance. In Personnel Selection in Organizations; Schmitt, N., Borman, W.C., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 35–70. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, M.A.; Neal, A.; Parker, S.K. A new model of work role performance: Positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bartram, D. The Great Eight competencies: A criterion-centric approach to validation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1185–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- O’Boyle, E.H.; Humphrey, R.; Pollack, J.M.; Hawver, T.H.; Story, P.A. The relation between emotional intelligence and job performance: A meta-analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 788–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, S.J.; Logel, C.; Davies, P.G. Stereotype threat. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2016, 67, 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ericsson, K.A. Deliberate Practice and Acquisition of Expert Performance: A General Overview. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2008, 15, 988–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H.; Koenka, A.C. The overview of reviews: Unique challenges and opportunities when research syntheses are the principal elements of new integrative scholarship. Am. Psychol. 2012, 67, 446–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.; Alberts, H.; Anggono, C.O.; Batailler, C.; Birt, A.R.; Brand, R.; Brandt, M.; Brewer, G.; Bruyneel, S.; et al. A multilab preregistered replication of the ego-depletion effect. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 11, 546–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rhodes, M.G. Age-related differences in performance on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Aging 2004, 19, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hyde, J.S. Gender Similarities and differences. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 373–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Westrick, P.A.; Le, H.; Robbins, S.B.; Radunzel, J.M.R.; Schmidt, F.L. College performance and retention: A meta-analysis of the predictive validities of ACT scores, high school grades, and SES. Educ. Assess. 2015, 20, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A. The Psychology of Behaviour at Work: The Individual in the Organization; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langelaan, S.; Bakker, A.; van Doornen, L.J.; Schaufeli, W.B. Burnout and work engagement: Do individual differences make a difference? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2006, 40, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, S.A.; Patterson, F.C.; Koczwara, A.; Sofat, J.A. The value of being a conscientious learner. J. Work. Learn. 2016, 28, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Janasz, S.; Crossman, J. Teaching Human Resource Management: An Experiential Approach; Elgar Guides to Teaching; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldham, G.R.; Fried, Y. Job design research and theory: Past, present and future. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2016, 136, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, M.; Zarola, A.; Palaiou, K.; Furnham, A. Work-related well-being. Health Psychol. Open 2016, 3, 2055102916628380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chung, B.G.; Dean, M.A.; Ehrhart, K.H. Inclusion values, practices and intellectual capital predicting organizational outcomes. Pers. Rev. 2021, 50, 709–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieder, R.E.; Wang, G.; Oh, I.-S. Linking job-relevant personality traits, transformational leadership, and job performance via perceived meaningfulness at work: A moderated mediation model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.P.; Wiernik, B.M. The Modeling and Assessment of Work Performance. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 47–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rothmann, I.; Cooper, L.C. Work and Organizational Psychology; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motowidlo, S.J. Implicit Trait Policies in Personality Research. Eur. J. Personal. 2017, 31, 472–473. [Google Scholar]

- Lassnigg, L. Competence-based education and educational effectiveness: A critical review of the research literature on outcome-oriented policy making in education. In Competence-Based Vocational and Professional Education: Bridging the World of Work and Education; Mulder, M., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 667–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotundo, M.; Sackett, P.R.; Enns, J.R.; Mann, S. Refocusing Effort Across Job Tasks: Implications for Understanding Temporal Change in Job Performance. Hum. Perform. 2012, 25, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, M.R.; Mitchell, T.R.; Stewart, G.L. Situational and Motivational Influences on Trait Behavior Relationships; Josey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 362–364. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, M.-Y.; Chan, I.Y.S.; Cooper, C.R. Stress Management in the Construction Industry; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenck, M.W. Attention and Arousal: Cognition and Performance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockey, R.J.; Gaillard, W.K.A.; Coles, M.G.H. Energetics and Human Information Processing; Behavioural and Social Science; NATO ASI Series; Springer Science & Business Media: Drechtsteden, Danmark, 1986; ISBN -13-978-94-010-8479-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Frederikslust, R.A.I. Predictability of Corporate Failure: Models for Prediction of Corporate Failure and for Evaluation of Debt Capacity; Martinus Nijhoff Social Sciences Division: Boston, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, J.L. A Review of the Empirical Ethical Decision-Making Literature: 2004–2011. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 117, 221–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ahlstrom, D. Risk-taking in entrepreneurial decision-making: A dynamic model of venture decision. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2019, 37, 899–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/main/data/database (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- TMF Group, Global Business Complexity Index 2021. Available online: https://www.tmf-group.com/en/news-insights/publications/2021/global-business-complexity-index (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Williamson, J.B.; Karp, D.A.; Dalphin, J.R.; Grey, P.S. The Research Craft; Little, Brown: Boston, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Predicting the performance of measures in a confirmatory factor analysis with a pretest assessment of their substantive validities. J. Appl. Psychol. 1991, 76, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerlinger, F. Foundations of Behavioural Research; Holt, Rinehart, Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, J.K.; MaCcallum, R.C.; Tait, M. The application of exploratory factor analysis in applied psychology: A critical review and analysis. Pers. Psychol. 1986, 39, 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Araujo, L.M.; Dubois, A. Research Methods in Industrial Marketing Studies; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2004; pp. 207–228. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, A.; Gadde, L.-E. Systematic combining: An abductive approach to case research. J. Bus. Res. 2002, 55, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbert, M.; Ruigrok, W. The What and How of Case Study Rigor: Three Strategies Based on Published Work. Organ. Res. Methods 2010, 13, 710–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, M.R.; Mount, M.K.; Judge, T.A. Personality and performance at the beginning of the new millennium: What do we know and where do we go next? Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2001, 9, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ones, D.S.; Dilchert, S.; Viswesvaran, C.; Judge, T.A. In support of personality assessment in organizational settings. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 995–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, M.R.; Mount, M.K. The Big Five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Pers. Psychol. 1991, 44, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, C.M.; Ones, D.S.; Sackett, P.R. Interpersonal deviance, organizational deviance, and their common correlates: A review and meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 410–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derue, D.S.; Nahrgang, J.D.; Wellman, N.; Humphrey, S.E. Trait and behavioral theories of leadership: An integration and meta-analytic test of their relative validity. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 7–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaburu, D.S.; Oh, I.-S.; Berry, C.M.; Li, N.; Gardner, R.G. The five-factor model of personality traits and organizational citizenship behaviors: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 1140–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Janowski, A. Personality Traits and Sales Effectiveness: The Life Insurance Market in Poland. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2018, 14, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hogan, J.; Holland, B. Using theory to evaluate personality and job-performance relations: A socioanalytic perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, J.F.; Anderson, N.; Tauriz, G. The validity of ipsative and quasi-ipsative forced-choice personality inventories for different occupational groups: A comprehensive meta-analysis. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 88, 797–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Connelly, B.S.; Ones, D.S. An other perspective on personality: Meta-analytic integration of observers’ accuracy and predictive validity. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 1092–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnambs, T. What makes a computer wiz? Linking personality traits and programming aptitude. J. Res. Personal. 2010, 58, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puryear, J.S.; Kettler, T.; Rinn, A.N. Relationships of personality to differential conceptions of creativity: A systematic review. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2017, 11, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.A.; Andrzejewski, S.A.; Yopchick, J.E. Psychosocial correlates of interpersonal sensitivity: A meta-analysis. J. Nonverbal Behav. 2009, 33, 149–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poropat, A.E. A meta-analysis of adult-rated child personality and academic performance in primary education. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 84, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McAbee, S.; Oswald, F.L. The criterion-related validity of personality measures for predicting GPA: A meta-analytic validity competition. Psychol. Assess. 2013, 25, 532–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vinchur, A.J.; Schippmann, J.S.; Switzer, F.S., III; Roth, P.L. A meta-analytic review of predictors of job performance for salespeople. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, J.F. The five factor model of personality and job performance in the European Community. J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Aarde, N.; Meiring, D.; Wiernik, B.M. The validity of the Big Five personality traits for job performance: Meta-analyses of South African studies. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2017, 25, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bing, M.N.; Lounsbury, J.W. Openness and Job Performance in U.S.-Based Japanese Manufacturing Companies. J. Bus. Psychol. 2000, 14, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minbashian, A.; Bright, J.E.H.; Bird, K.D. Complexity in the relationships among the subdimensions of extraversion and job performance in managerial occupations. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 82, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gridwichai, P.; Kulwanich, A.; Piromkam, B.; Kwanmuangvanich, P. Role of Personality Traits on Employees Job Perfor-mance in Pharmaceutical Industry in Thailand. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wihler, A.; Meurs, J.A.; Wiesmann, D.; Troll, L.; Blickle, G. Extraversion and adaptive performance: Integrating trait activation and socioanalytic personality theories at work. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 116, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, W.F.; Slocum, J.W. Top management talent, strategic capabilities, and firm performance. Organ. Dyn. 2012, 41, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.R. Why don’t measures of broad dimensions of personality perform better as predictors of job performance? Hum. Perform. 2005, 18, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, D.P. The Big Five related to risky sexual behaviour across 10 world regions: Differential personality associations of sexual promiscuity and relationship infidelity. Eur. J. Personal. 2004, 18, 301–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, F.P.; Campion, M.A.; Dipboye, R.L.; Hollenbeck, J.R.; Murphy, K.; Schmitt, N. Reconsidering the use of personality tests in personnel selection contexts. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 683–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tett, R.P.; Christiansen, N.D. Personality tests at the crossroads: A response to Morgeson, Campion, Dipboye, Hollenbeck, Murphy, and Schmitt. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 967–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandler, C.; Bleidorn, W.; Riemann, R.; Angleitner, A.; Spinath, F.M. The genetic links between the Big Five personality traits and general interest domains. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 37, 1633–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, C.E.; Kirkwood, T.B. Chance, Development, and Aging; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yerkes, R.M.; Dodson, J.D. The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. J. Comp. Neurol. Psychol. 1908, 18, 459–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schwartz, S.H. An Overview of the Schwartz Theory of Basic Values. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2012, 2, 2307-0919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieciuch, J.; Davidov, E.; Vecchione, M.; Beierlein, C.; Schwartz, S.H. The Cross-National Invariance Properties of a New Scale to Measure 19 Basic Human Values: A Test Across Eight Countries. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2014, 45, 764–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elbaek, C.T.; Lystbaek, M.N.; Mitkidis, P. On the psychology of bonuses: The effects of loss aversion and Yerkes-Dodson law on performance in cognitively and mechanically demanding tasks. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2022, 98, 101870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energia ze Źródeł Odnawialnych w Polsce (2022). Available online: https://portalstatystyczny.pl/energia-ze-zrodel-odnawialnych-w-polsce-najnowsze-dane/ (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- Pacini, R.; Epstein, S. The relation of rational and experiential information processing styles to personality, basic beliefs, and the ratio-bias phenomenon. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 972–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.L.; Robitaille, A.; Zelinski, E.M.; Dixon, R.A.; Hofer, S.M.; Piccinin, A.M. Cognitive activity mediates the association between social activity and cognitive performance: A longitudinal study. Psychol. Aging 2013, 31, 831–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1. Basic tendencies a. Individuality. All adults can be characterized by their position in relation to the set of personality traits that influence patterns of thinking, feeling and behavior. b. Origin. Personality traits are endogenous basic tendencies. c. Development. Traits develop through childhood and mature into adulthood (30 years of age); thereafter, they are stable in people without cognitive impairment. d. Structure. Traits are organized in a hierarchical manner, from narrow and specific dispositions to broad and general ones: neuroticism, extroversion, openness to experience, agreeableness and conscientiousness are at the highest level of this hierarchy. |

| 2. Characteristic adaptations a. Adaptation. Over time, individuals respond to their environment by forging patterns of thinking, feeling and behavior that align with personality traits and previous adaptations b. Maladaptation. At any point in time, adjustments may not be optimal for cultural values or personal goals. c. Flexibility. Characteristic adaptations change over time in response to biological maturation, changes in the environment or intentional interventions. |

| 3. Objective biography a. Multiple determination. Action and experience are at all times complex functions of all the characteristic adaptations determined with the environment. b. Course of life. Individuals have plans, schedules and goals that enable the activity to be organized over extended periods of time in a manner compatible with their personality traits. |

| 4. Self-image a. Schemes “I”. Individuals maintain a cognitive-affective view of themselves, that is available to consciousness. b. Selective perception. Information is selectively represented in the self-image so that it is consistent with the personality traits and gives the person a sense of consistency. |

| 5. External influences a. Interaction. The social and physical environment interacts with the dispositions of the personality to shape characteristic adaptations and interacts with characteristic adaptations to regulate the course of behavior. b. Perception. People perceive the environment and construct it in a way that is compatible with their personality traits. c. Reciprocity. People selectively act on the environment to which they respond. |

| 6. Dynamic processes a. Universal dynamics. A person’s continual activity toward the creation of adaptations expressed in thoughts, feelings and behaviors is governed to some extent by universal cognitive, affective and volitional mechanisms. b. Differential dynamics. Some dynamic processes are differentially influenced by an individual’s underlying tendencies (including personality traits). |

| Statistics | The Trait in BIG5 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | C | E | A | N | ||||||

| ent. | con. | ent. | con. | ent. | con. | ent. | con. | ent. | con. | |

| Mean | 67.4 | 73.0 | 67.6 | 75.1 | 67.6 | 54.1 | 78.1 | 72.0 | 34.6 | 42.7 |

| SD | 11.8 | 7.7 | 19.9 | 7.0 | 13.5 | 11.2 | 11.5 | 7.2 | 13.3 | 9.4 |

| Minimum | 33 | 56 | 27 | 62.5 | 25 | 37.5 | 35 | 56 | 2 | 17 |

| Q25 | 62.5 | 71 | 48 | 69 | 58 | 48 | 69 | 69 | 27 | 42 |

| Median | 70 | 74 | 73 | 75 | 71 | 51 | 79 | 73 | 35 | 47 |

| Q75 | 74 | 77 | 86.75 | 80 | 77 | 52.5 | 87.5 | 78 | 40.5 | 48 |

| Maximum | 90 | 90 | 100 | 92 | 92 | 81 | 100 | 81 | 81 | 52 |

| Averages test | 0.0342 | 0.0877 | 0.0000 | 0.0183 | 0.0074 | |||||

| Variance test | 0.0363 | 0.0000 | 0.2518 | 0.0066 | 0.1250 | |||||

| O | C | E | A | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | −0.3341 | 0.2149 | −0.0872 | −0.0536 | |

| 0.2932 | 0.2099 | 0.2346 | 0.2183 | ||

| C | −0.3341 | −0.1506 | 0.2356 | −0.1554 | |

| 0.2932 | 0.0405 | 0.5306 | 0.4574 | ||

| E | 0.2149 | −0.1506 | −0.2106 | 0.0209 | |

| 0.2099 | 0.0405 | −0.3295 | −0.0284 | ||

| A | −0.0872 | 0.2356 | −0.2106 | −0.2672 | |

| 0.2346 | 0.5306 | −0.3295 | 0.2156 | ||

| N | −0.0536 | −0.1554 | 0.0209 | −0.2672 | |

| 0.2183 | 0.4574 | −0.0284 | 0.2156 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Janowski, A.; Szczepańska-Przekota, A. The Trait of Extraversion as an Energy-Based Determinant of Entrepreneur’s Success—The Case of Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 4533. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15134533

Janowski A, Szczepańska-Przekota A. The Trait of Extraversion as an Energy-Based Determinant of Entrepreneur’s Success—The Case of Poland. Energies. 2022; 15(13):4533. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15134533

Chicago/Turabian StyleJanowski, Andrzej, and Anna Szczepańska-Przekota. 2022. "The Trait of Extraversion as an Energy-Based Determinant of Entrepreneur’s Success—The Case of Poland" Energies 15, no. 13: 4533. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15134533

APA StyleJanowski, A., & Szczepańska-Przekota, A. (2022). The Trait of Extraversion as an Energy-Based Determinant of Entrepreneur’s Success—The Case of Poland. Energies, 15(13), 4533. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15134533