1. Introduction

Energy poverty describes the situation where households are unable to afford or access adequate household energy services [

1,

2,

3]. Energy use is essential for daily living as it affects important housing-related pathways to health outcomes, such as temperature control, water supply, waste removal and air quality [

4,

5,

6]. Considerable research has demonstrated the links between housing and health, with poor housing conditions increasing the risk of mental health problems and respiratory, cardiovascular, circulatory and nutrition-related illnesses [

7,

8]. Living in energy poverty is known to be harmful to health and wellbeing, contributing to a range of acute and chronic health outcomes [

4,

9,

10]. Temperature control is a critical component of a healthy home, with households considered to be in energy poverty often experiencing below recommended temperatures [

11]. Based on the strength of the evidence that temperatures below recommended levels are harmful to health, the World Health Organization (WHO) continues to recommend 18 °C as a minimum safe indoor temperature [

7].

Energy poverty in New Zealand is well-documented, with previous estimates indicating that 25% of New Zealanders were living in energy poverty [

11]. However, a nationally accepted official definition of and measurement strategy for energy poverty are still in development [

12,

13], following a recent electricity market sector review [

14]. Household electricity prices in New Zealand are in line with the OECD average at approximately USD 0.20 per kWh. However, New Zealand has relatively poor-quality housing [

15,

16], which is a significant contributing factor to energy poverty and remains a key reason that raising household incomes alone will not eliminate energy poverty in New Zealand [

17,

18]. The 2018 Census and General Social Survey data confirmed the widespread extent of housing quality issues in New Zealand, including mould, dampness and inadequate temperatures [

15]. Statistics NZ carries out the General Social Survey to provide information on the well-being of New Zealanders aged 15 years and over. It surveys a wide range of social and economic outcomes. In the 2018 General Social Survey, which was undertaken face-to-face, an on-the-spot temperature reading was taken of approximately 6700 homes, and 33% were recorded to be under the minimum 18 degrees recommended by the World Health Organization [

15]. Moreover, 21.2% of those surveyed reported their homes were too cold [

15]. Renters, those aged 15–24 and low-income households were among those who were more likely than the general population to report feeling cold in their homes [

15].

Studies exploring energy poverty among tertiary student population groups in England [

19,

20,

21], Europe [

22,

23], and Japan [

24] have confirmed that tertiary students are at greater risk compared to the general population. Poor housing conditions, particularly in the private rental sector, contribute to adverse mental and health outcomes among tertiary students [

19,

22]. As with other studies of private rental sector landlords [

16,

25,

26], a qualitative study of landlords in seven EU countries found that landlords with properties predominantly leased by students are unlikely to make energy efficiency improvements to their rental housing without financial incentives and regulatory measures. During the COVID-19 pandemic, public health measures, including a stay-at-home order, have increased the burden of energy poverty among at-risk groups, including the student population [

27]. The stay-at-home measures notably increased the need for households to make trade-offs between achieving thermal comfort and paying other bills [

28].

There have been very few New Zealand studies on student housing and wellbeing in recent years. A survey conducted in 2003 in Dunedin, New Zealand, investigated the quality of the housing stock in the southern university city and its impacts on the health of occupants [

29]. More than 70% of respondents claimed to experience mould, dampness and droughts, and 61% did not find their flat comfortable in winter. More than 75% wanted to live in a better-insulated property, and over half thought better insulation would improve their quality of life [

29]. A 2015 study investigating high school students’ experiences of energy poverty found that Year 10 students (aged 14–16) expressed higher rates of poor thermal comfort indicators than adults [

30].

In 2018 the New Zealand Union of Students’ Associations produced the Kei Te Pai Report on tertiary student mental health in New Zealand [

31], which identified financial and living situation stressors as significant contributing factors harming students’ mental health. This report confirmed that how students feel about their financial situation, with whom students live and how satisfied students are with their living situation all substantially impact their levels of psychological distress. Several respondents also commented that “flatting” (the colloquial term for house-sharing in New Zealand), “landlords”, “sub-par living conditions”, “cold weather” and “affording rent” were all stressors that triggered their depression, stress and anxiety [

31].

Despite students having been identified as an at-risk group, there has been very little research on tertiary students’ experiences of energy poverty in New Zealand. This study aimed to contribute to this knowledge gap by investigating the extent and impact of energy poverty among New Zealand tertiary students. Furthermore, it aimed to identify disparities between different demographic groups, understand the effects of COVID-19 and evaluate the effectiveness of the support policies available to students.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

Responses from 522 students were analysed, and their demographic information is summarised in

Table 1. Of those, 376 were female, 132 were male, and 12 were gender-diverse—indicating that female students (72.3%) were significantly more likely to respond to the survey. More than half of the survey participants (55.9%) were aged between 19 and 23. Fourteen per cent of participants identified as Māori, 5.8 % as Tangata Pasifika, 20.6 % as Asian, and 67.7% as European. In this survey, 14.9% of total participants indicated two or more ethnicities. In addition, 71 students (14.2%) reported having long-term disabilities or health concerns.

Most respondents were either studying at a university (49.6%) or a polytechnic or institute of technology (47.3%). Only 5.4% of respondents were studying at private training establishments, workplace training or Wānanga. The regional distribution of respondents reflected the locations of major tertiary education providers.

Overall, flatting was the most common accommodation arrangement for students who responded to the survey (65.3%), followed by living with family (18.8%) and hall of residence or hostel (8.8%). However, as expected, there were differences between age groups. For example, students aged 18 years or under were more likely to live with their family (50.0%) or in a hall of residence or hostel (25.0%) than flatting (16.7%). On the other hand, students aged 30 years old or over were rarely in a hall of residence or hostel (1.3%), but it was more common for them to have other arrangements (17.9%) that were not listed in the survey response, such as owning their own home.

3.2. Housing Quality and Thermal Comfort

The survey findings indicated a lack of healthy housing and suggested a large proportion of students living in poor quality dwellings. They also indicated that students with long-term disabilities or health concerns and of Māori ethnicity were disproportionally impacted (see

Table 2).

Overall, mould and dampness were common, with 34.9% of students seeing mould larger than an A4 sheet of paper at least some of the time and 48.8% of students reporting that their dwelling was sometimes or always damp. Compared to the 2018 New Zealand Census, where 16.9% of homes had a visible mould of the same dimensions and 21.5% of homes were affected by dampness [

15], tertiary students are disproportionately affected by mould and dampness. The difference between the overall population and the tertiary students surveyed demonstrated here is significant, even after considering the different reporting approaches taken from the same set of questions. The New Zealand Census reported the presence of mould and dampness per dwelling. However, in this report, the presence of mould and dampness is reported per respondent, where there is a possibility that two or more respondents are from the same dwelling.

Additionally, the 2018 New Zealand Census also reported that Māori and Tangata Pasifika were more likely to live in housing with mould and dampness than other ethnicities [

15]. Our survey also demonstrated that students identifying as Māori were more likely to report mould larger than an A4 sheet being present sometimes or always (46.7%) than non-Māori students (31.7%) (

p < 0.05). Furthermore, students with long-term disabilities or health concerns reported mould larger than an A4 sheet (49.3%) at a higher rate than students without any long-term disability or health concern (

p < 0.01).

Most students experienced shivering inside their dwelling (78.8%), and 26.9% of respondents reported that it happened regularly. Students with long-term disabilities or health concerns were much more likely to report shivering more than three times or regularly in the year surveyed compared to those without any health concerns (p < 0.05). Two thirds (67.0%) of students could see their breath indoors, and 23.6% of respondents said it was a regular occurrence. These physiological indicators signal that a large proportion of students were experiencing indoor temperature below the WHO-recommended minimum healthy indoor temperature of 18 °C at least some of the time. More subjective indicators provided further evidence of students being unable to achieve thermal comfort. Respondents widely reported feeling cold inside their dwellings often or always (65.3%), and even when using a heater, one in ten students (10.4%) said they still felt cold often or always.

Nearly a third of respondents (32.5%) said they either did not have a heater or did not use it due to always being concerned about energy bills. Instead, students reported a broad range of initiatives to mitigate feeling cold in their dwelling. The most commonly mentioned was using hot water bottles to warm the body directly, which is known to have a significant, but largely preventable, impact on the burden of morbidity and cost from hot water bottles induced thermal injuries and burns injuries [

40]. It was followed by donning extra clothing or blankets or using an electric blanket, or heat packs or wheat bags. Some also reported that they actively avoid being at home and spend time at the heated indoor areas on the campus as much as possible. A more concerning finding was that 24 respondents reported explicitly having no strategy to cope with feeling cold in the dwelling. Ten respondents reported using a cooking oven as a heater, which is less effective than using a heater and is a potential fire hazard or, in the case of gas ovens, there is a risk of carbon monoxide poisoning [

41]. Where there is no other heating source available, this is a method that households experiencing energy poverty may resort to for space heating.

Despite the high prevalence of mould and dampness, lack of insulation and double-glazing and being unable to achieve thermal comfort in students’ dwellings, only 9.2% of respondents described the condition of their dwelling as “poor” or “very poor”. When assessing how satisfied students were with their housing situation, 67.2 was the mean level of satisfaction on a 0–100 scale ranging from very unsatisfied (0) to very satisfied (100). However, the average satisfaction level varied between the accommodation types. For example, students flatting at a private accommodation reported the lowest level of satisfaction with their dwelling, with an average score of 61. The highest average satisfaction (89) was reported by the small number of students (14 students: 2.7%) living in a homestay or private boarding accommodation. Students living in a residence hall or hostel and those living with family also reported higher satisfaction levels with their dwellings at 79. Given that younger students tend to be in these accommodation types, students in their first year of study or aged between 16 and 18 were more likely to report higher satisfaction with their accommodation arrangements, respectively, averaging at 72 and 77.

3.3. Health and Wellbeing

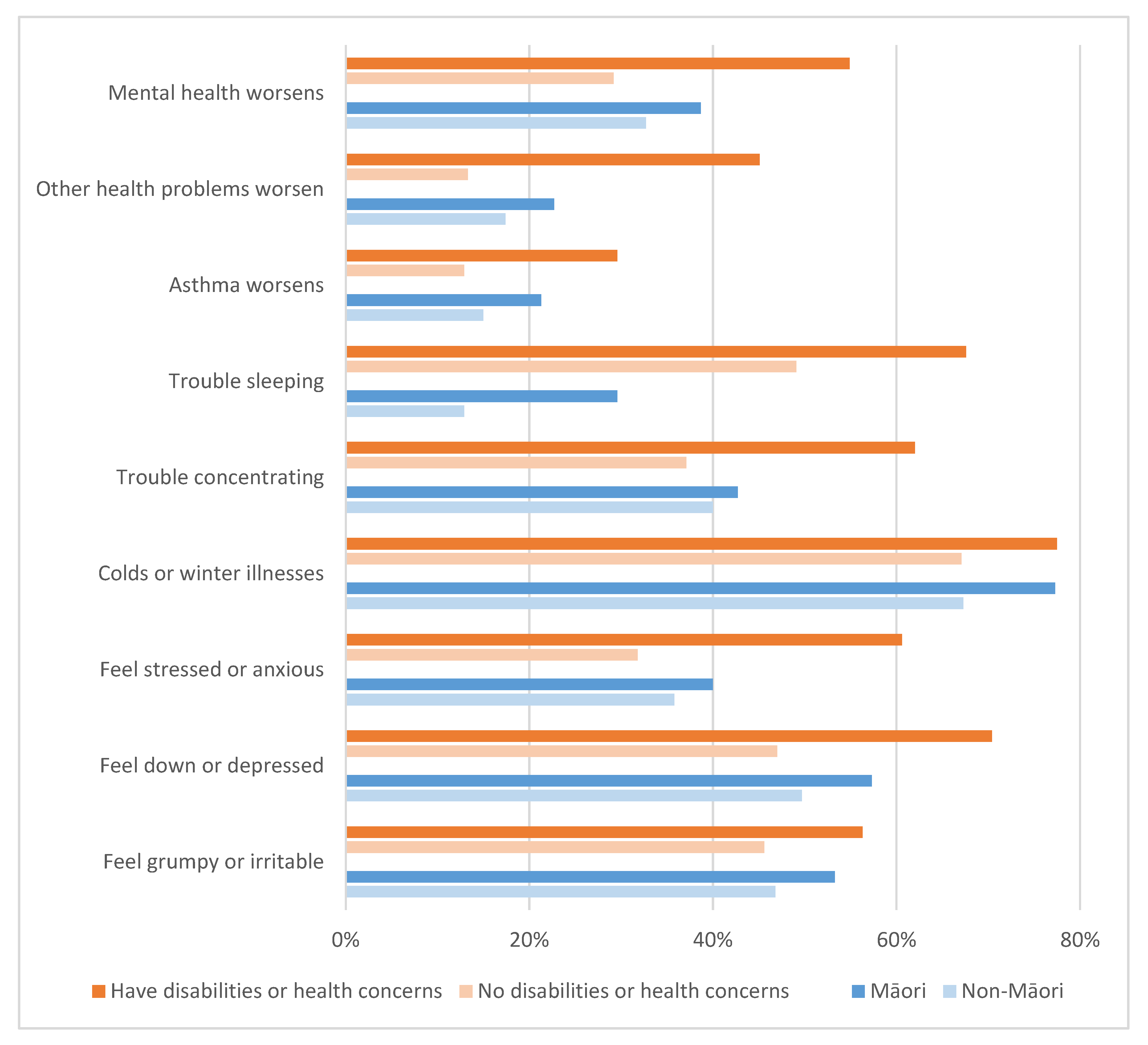

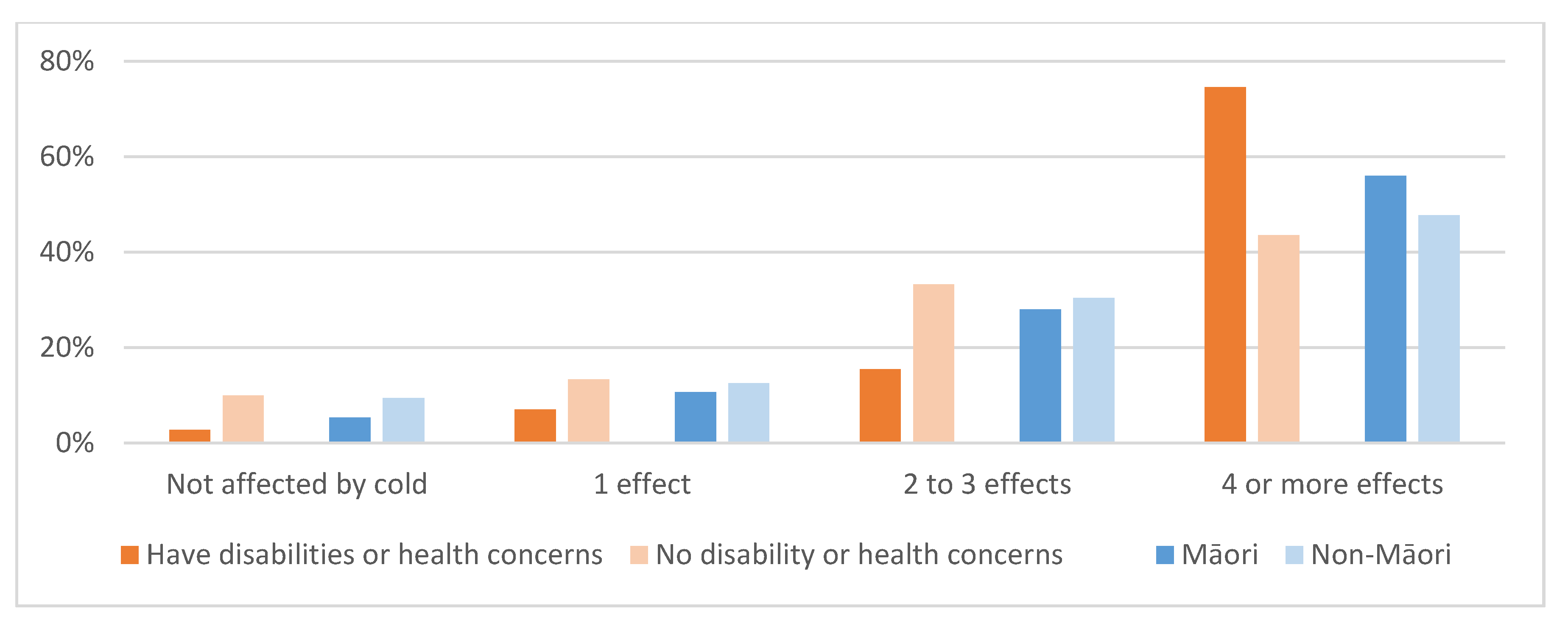

To explore the impacts of energy poverty, we asked students general questions about their health and wellbeing. The findings indicated that energy poverty significantly impacted students’ ability to carry out daily activities and mental health. The most concerning result was that students with long-term disabilities or health concerns were disproportionally affected. The survey asked about four typical home activities of students—socialising (i.e., having other people invited over), studying, daily tasks (i.e., drying clothes, using the bathroom) and getting out of bed—and how often these activities are restricted due to the dwelling condition. In all four activities, students with long-term disabilities or health concerns were significantly more likely to report being restricted (see

Table 2). Furthermore, being cold in the dwelling due to energy poverty negatively affected students’ general wellbeing, with almost half (48.9%) of respondents reporting to have experienced four or more wellbeing measures out of nine listed in the survey. Again, there was statistically significant evidence that students with long-term disabilities or health concerns were disproportionally affected, as displayed in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

Our results also identified that students had poorer subjective health than the general adult population. Only 40.8% of students rated their health as “very good” or “excellent” compared to 55.3% of the general population. In contrast, one in four students (25.2%) rated their health as “fair” or “poor,” compared to just one in ten of the general population (10.5% for aged between 15 and 24; 11.1% for aged between 25 and 34) [

42]. Students also rated their overall life satisfaction lower than the general population. When asked how they felt about their life as a whole, 57.7% of respondents rated their life satisfaction at 70 or higher on a 0–100 scale, where 0 is completely dissatisfied and 100 is completely satisfied. Our result was significantly lower than the comparable nationwide result from the 2018 General Social Survey, where 82.5% of respondents aged between 15 and 24 and 81.6% of respondents aged between 25 and 34 rated their overall life satisfaction at a seven or higher on the scale of zero to ten [

42].

Disparities between demographic groups were again evident in the students’ experience of energy poverty. Among the various demographic groups, students with long-term disabilities or health concerns were the most disadvantaged. For example,

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 illustrate the differences in the experience of energy poverty between students with long-term disabilities or health concerns, students who identified as Māori and students who did not identify as Māori. Students who did not identify as Māori were least restricted and affected by energy poverty in all measures surveyed, whereas the students with long-term disabilities or health concerns were the most restricted and affected. Three in four students with disabilities or health concerns (74.6%) reported having experienced four or more negative effects of feeling cold indoors out of ten response categories provided. In contrast, approximately one in two students who identified as Māori (56.0%) and students who did not identify as Māori (48.9%) reported the same.

Furthermore, the gap between the general population and tertiary students surveyed in our study becomes more significant when demographic disparities are considered. The 2018 General Social Survey reported that respondents with the disability status reported much lower life satisfaction (64.7% reported seven or higher) and self-rated general health (48.6% said as “fair” or “poor”) than those without the disability status. The same trend was replicated in the tertiary students who indicated disability or health concern but at a much worse rate. Among the latter, only 37.3% reported their life satisfaction as 70 or higher, and 64.8% rated their general health as “fair” or “poor”. In general, the results indicated that tertiary students’ health and wellbeing are affected negatively by energy poverty at a much higher rate than the general population. Further, students with existing disabilities or health concerns are more marginalised with even less adequate support than their counterparts among the general population for factors that impact wellbeing, including, but not limited to, energy poverty.

3.4. Financial Insecurity and Energy Poverty Indicators

Financial insecurity was common among students. Most respondents (69.3%) juggled more than one income source; borrowing from the Student Loan Scheme–Living Costs. StudyLink is an NZ government agency that administers the major support policies for tertiary students: The Student Loan Scheme and the Student Allowance Scheme. The Student Loan Scheme provides students with access to interest-free finance for tuition fees, living costs and other education-related costs to reduce cost barriers to tertiary education. The Student Loan Scheme–Living Costs allows students to borrow money from the government in order to subsidise living expenses. The money borrowed will need to be repaid once they start earning over a certain income threshold. The maximum amount students can borrow is adjusted to the Consumer Price Index (CPI) each year. In 2020, students were able to borrow up to NZD 228.81 a week. This was the most common (54.4%) source of finance, followed by wages paid by an employer (48.1%). However, nearly half of the respondents indicated limited or absent financial support network: 46.5% of students reported a score of 30 or less when asked if they were comfortable asking for financial help from other people, such as family members (where 0 is very uncomfortable and 100 is very comfortable).

Regarding managing energy bills, more than half of students (55.4%) said they had to juggle. However, other indicators suggested that this number was significantly under-representing the financial hardships that students were experiencing. For many students, concerns over the affordability of energy bills restricted a number of daily domestic activities. Most notably, 74.1% of students responded that they had refrained from heating their dwelling due to concerns over energy bills. It was significantly higher (

p < 0.05) for students with long-term disabilities or health concerns at 84.3%. Furthermore, these students also reported a much higher rate of restricting other daily domestic activities, such as showering, cooking food and doing laundry (see

Table 3).

Interestingly, more than a quarter of respondents (27.6%) altered their energy use patterns to take advantage of deals offered by their power companies, such as a free “off-peak hour of power” per day or a “weekend of free power” per month. Although nearly a third of respondents (31.3%) who utilised deals reported that this was difficult to keep up with, and 18.8% found it could cause tension among flatmates, 40.3% of respondents said the financial benefits made it worthwhile.

Overall 4.3% of students had had their electricity disconnected or ran out of prepaid credit for electricity because their household could not afford to pay the energy bill, which was more than six times the national rate (4.3%) [

43]; furthermore, it was reported by Māori students at a rate more than four times higher (12.5%) than by non-Māori students (2.9%) (

p < 0.001).

3.5. Narrative Statements

The most common theme that arose from open-ended questions probing deeper on the impact of the energy poverty experienced by students was having to make conscious compromises between daily essentials, as seen in student 231’s comment: “I avoid buying food [and] other necessities to ensure I can afford power”. However, compromises were not limited to affording essentials. It extended to their health and wellbeing: “expenses push me to choose ‘being grumpy’ and ‘living in a colder condition’” (student 52), “you are paying for it with poor mental and physical health” (student 66); time and effort for studies: “work harder to afford the bill […] means reduced focus on the study” (student 52); and future liabilities: “I have an extra $1000 in debt because I wanted to stay warm” (student 35).

At the same time, there was a sense of helplessness and a reluctant acceptance of the status quo among students, which was expressed through the language that normalised the poor quality, unaffordable dwelling conditions. Students thought “realistically no one can [afford] anyway” (student 57), some did not feel the cold dwelling affected them despite “know[ing] it was terrible for me” (student 60) and others used humour to describe their poor living conditions, one student commenting “[my partner from the UK] charitably describes the experience of living in our unheated old villa as ‘indoor camping’” (student 71).

Many students identified a high residential rental cost as the major contributing factor to their energy poverty or the experience of poverty in general. Housing costs were so high that one student reported that the rent was 90% of their income available under the Student Loan Living Costs scheme. Many students felt that the high rent cost was unjustified considering the poor dwelling conditions, which they often described as having deferred maintenance, disgusting, mouldy, droughty and cold.

Overall, the analysis of open-ended responses echoed the findings noted earlier; most students were acutely aware of how they were negatively affected in their experience of energy poverty. Living in a damp, mouldy indoor environment led to being “physically sick” (student 35) for some and, in a worse case, “being hospitalised with a chest infection” (student 287). It also “cause[d] asthma to worsen” (student 20), and “impact[ed] overall wellbeing” (students 66). Being constantly cold at home also affected students’ mental health in significant ways with reports of “taking anti-anxiety medication [and] one of the main stressors at that time was how cold I was” (student 101), “hypervigilance and depression” (student 12) and “feel[ing] gross and unhappy in yourself” (student 57). Furthermore, students with dependent family members were reporting how adverse impacts experienced by other household members: “hayfever being more persistent in my wife, and increased skin irritation in my son and wife” (student 324) and “[my] child was hospitalised with pneumonia” (student 69). Students strongly desired affordable, healthy living conditions. As one student put it: “having a private, warm place to rest every day is key for my wellbeing” (student 281).

4. Discussion

4.1. Tertiary Students’ Experience of Energy Poverty

The findings from the nationwide survey of 522 students in New Zealand indicated a prevalent energy poverty experience among tertiary students, which restricted their daily activities and negatively affected their physical and mental health. Furthermore, it highlighted how energy poverty disproportionally affected students with long-term disabilities or health concerns and students who identified as Māori. Despite students facing ever-increasing housing costs, the survey findings make apparent that the support available for students is inadequate and has limited availability. It reflects how the student population had been neglected in the research into energy poverty and conditions of student accommodation and the lack of evidence led to inadequate policy responses.

Overall, our findings suggest that students are more likely to restrict their energy use and put up with cold temperatures than risk disconnection from the energy services. As a result, they experience hindrances to their daily activities and studies, in addition to negative impacts on their physical and mental health. The disconnection rate reported by students was 4.3% overall, which is more than six times compared to the general population. For the general population using standard billing or post-payment methods, the disconnection rate was approximately 0.67% in 2020 [

43]. Prepayment consumers typically experience much higher rates of disconnection than those using standard billing or post-payment methods [

44]. Disconnection for non-payment by prepayment meter consumers, where the meter has ‘run out of credit’ and is automatically shut-off, is known in the electricity industry as ‘self-disconnection’, although this problematically implies the consumer has agency to make a choice to disconnect, which may not exist among energy-poor households. In a national survey undertaken in 2010, 53% of prepayment meter consumers reported disconnection for non-payment in the past 12 months, lasting for 12 or more hours among 38% of those who disconnected [

44]. However, these data were not collected in official national statistics; therefore, no comparison for 2020 can be provided.

Our findings closely align with the existing international literature. European [

22,

23] and Japanese studies [

24] have shown that tertiary students are at greater risk compared to the general population, with poor housing conditions, particularly in the private rental sector, driving this difference [

19,

22]. Internationally there is a recognised need for regulation to encourage energy efficiency improvements in the private rental sector [

16,

25,

26]; our study shows that better regulation is needed in New Zealand too.

A typical accommodation arrangement for tertiary students in New Zealand starts with living in a hall of accommodation with support services in the first year and moving on to flatting in the privately-rented residential properties in each of the subsequent years. Therefore, student tenancies are inherently short-term, and often the local rental market is geared to exploit this nature [

45]. (i.e., Leases are only offered as a one-year fixed term to avoid summer vacancies; Lease renewal dates are in February, which maximises competition among students starting the academic year in March.) There already exists split incentives between the landlord and tenants; the landlord aims to maximise rental revenue while minimising costs, and the tenant wishes to minimise housing costs while maximising the utility or comfort from the housing [

26]. Short-term student tenancies inevitably exacerbate the existing split incentives; neither landlords nor students have incentives to implement energy-efficient measures to the residential property with high upfront costs in the short term.

The findings also indicated information asymmetry. When asked about the existence of insulation, only 53.9% of students could confirm that their dwelling had ceiling insulation, 46.5% had wall insulation and 39.9% had underfloor insulation. However, for each category, over 20% of respondents were unsure if they had insulation or not. It suggests a lack of transparency by accommodation providers, be it the tertiary education provider or private landlord. The accommodation providers are not actively providing relevant information for understanding the heating costs of the accommodation in an easily accessible manner in advance of entering into the tenancy agreement [

17]. Introducing Energy Performance Certificates for rental properties would help fix this problem by making the expected energy costs to maintain healthy temperatures known to tenants before they rent the accommodation. It would also put a value on energy performance above the minimum required standards for homes that perform at higher levels [

18]. While there are some regulations (for example, the Residential Tenancies (Healthy Homes Standards) Regulations 2019) to improve the energy efficiency of private rental accommodation, more is needed to incentivize landlords to act. (The current legislation can be read here:

https://www.legislation.govt.nz/regulation/public/2019/0088/latest/whole.html, last accessed 17 December 2021).

One interesting finding from the survey was that students rated their dwelling relatively in a good light despite the experience of energy poverty in the poor dwelling conditions. Our result also aligns with the Kei Te Pai Mental Health Report, which surveyed tertiary students across New Zealand to form an overview of the state of tertiary students’ mental health in 2018 [

31]. In the Kei Te Pai Mental Health Report, only 18.5% of students were explicitly unhappy with their living situation. Both findings indicate that other factors than housing quality—such as the cost of renting or the proximity to the education provider—are being prioritised by students when making housing decisions, which conversely lead to lower quality housing options and the subsequent impact on their health and wellbeing [

20]. In addition, energy costs are often lumped with other household expenses into “utility expenses” or embedded into the overall accommodation payment in the context of student accommodations and household practices. Therefore, it is easy for students to ignore them and not consider themselves to be living in energy poverty [

20].

4.2. Support Policies Addressing Student Energy Poverty

A number of government support policies are available in New Zealand to help low-income individuals or families experiencing energy poverty. However, tertiary students are often not included as a target population for such policies. There is a general lack of support policies that tertiary students can easily access. If they exist, their availability is poorly communicated to the students. For example, StudyLink can provide students with a grant of up to

$200 to help with outstanding power bills or reconnecting supply [

46]. However, despite most respondents showing indicators that they were experiencing energy poverty, only 7.1% of them had contacted StudyLink for help with utility bills. Of the respondents who did not contact StudyLink for utility bills (90.8%), 92.2% were unaware that such assistance was available, and 44.6% said they may have used it if they had known.

The current major government policy to address energy poverty among the vulnerable population is the Winter Energy Payment, which came into effect in July 2018. It is an additional payment to the existing recipients of eligible government benefits and is universally applied to those receiving government superannuation. It is available between May and October each year [

47]. However, tertiary students were unlikely to qualify to receive it as the primary government benefit available for tertiary students (the Student Allowance scheme: 32.8% of respondents were recipients) is not included in the eligible benefits list for the Winter Energy Payment. Furthermore, many eligible government benefits for the Winter Energy Payments are mutually exclusive with benefits for tertiary students. The Jobseeker Support Student Hardship payment is the only benefit targeted to students (7.5% of respondents were recipients) who were eligible for the Winter Energy Payment. Jobseeker Support Student Hardship is a weekly payment to help with students’ living expenses during a study break of more than three weeks. However, most tertiary institutions’ long semester breaks take place in the summer months from November to March, rather than winter. Thus, it is not surprising that only one in ten survey respondents (10.0%) had received the Winter Energy Payment.

For those students who received it, their benefit receipts were increased by

$40.92 a week for single people without dependent children and

$63.64 a week for couples or people with dependent children between 1 May 2020 and 1 October 2020. The Winter Energy Payment rate for the year 2020 was doubled from the original rate in previous years as the government responded to the impact of COVID-19 and implemented support packages. However, among the students who received it, the average rating of its effectiveness at maintaining a comfortable indoor temperature was only 52.1 out of 100 (where 0 is not effective and 100 is very effective). This is supported by evidence from a study undertaken in Wellington, New Zealand, which found that the Winter Energy Payment rate would not cover the costs of heating a child’s bedroom to a healthy indoor temperature [

48].

4.3. Impact of COVID-19 on Energy Poverty

In response to the emerging COVID-19 pandemic, the COVID-19 alert level system was put in place by the New Zealand government to contain community transmission of the virus in March 2020. Alert Level 4 was equivalent to a stay-at-home order and the first nationwide use of Level 4 began on 25 March 2020 and ended on 27 April 2020, with most people continuing to stay home at Level 3 which ended on 13 May 2020. When surveyed on the impact of the COVID-19, more than half of the students (56.1%) said that the COVID-19 Level 4 restrictions in early 2020 led to increased difficulties in affording utility bills permanently or temporarily. Students reported significantly increased energy use at home during the lockdown, in which in one instance, the energy bill had jumped from $200 to $500 per month. Furthermore, students reported having conflicts with other household occupants due to the differences in energy use expectations and abilities to afford increased energy bills.

Apart from the limited number of students who received the Winter Energy Payment at the increased rate, there was very little government support provided to the tertiary students during the COVID-19 level 4 restrictions. The only COVID-19 related government initiative targeted at tertiary students was that the Student Loan Course-related Costs scheme’s increased limit from $1000 to $2000. While the Student Loan Course-related Costs scheme is designed to help with any one-off study material costs (normally up to $1000 per year), many borrowers often use it to supplement any costs that arise from enrolling in the tertiary institutions (i.e., paying a bond for a residential tenancy or utility bills). The increased debt limit was taken up by 44.3% of survey respondents and 13.6% kept their borrowing within the original limit. It was notable that half of the students that withdrew the Student Loan Course-related Costs reported using some of the borrowed money to help with their energy costs, while 4.6% said they used the entirety to do so.

Justifiably, many students did not view the increased debt limit as a practical measure to provide support. As one student clearly noted in their comments, tertiary students were the only demographic in New Zealand that was provided with a government loan rather than government assistance in addressing the impact of COVID-19. Further analysis of the open-ended responses revealed that many respondents held strong resentment about the lack of government support for tertiary students, which they described as “pathetic” and does not come into effect until “desperation kicks in” rather than being preventive measures. The inadequate support for tertiary students is even more concerning because as the impact of poor dwelling conditions disproportionally affected students with long-term disabilities or health concerns, so did the impact of COVID-19 on energy poverty (p < 0.001). Students with long-term disabilities or health concerns were experiencing difficulties from the increased utility bills (30.0%) at more than twice the rate of students without long-term disabilities or health concerns (12.6%).

However, given that New Zealand society actively promotes higher education to improve the lives of students themselves and society [

49], the lack of appropriate measures to ensure the standard of student dwellings and support students experiencing energy poverty indicates policy failure. There has been some progress and increased advocacy in recent years, including the amendment to the Education Act that created a new mandatory Code of Practice setting out the duty of care required of tertiary providers [

50] and a Parliament Inquiry into Student Accommodation [

51]. The Education (Pastoral Care) Amendment Act 2019 came into place following the tragic death of Mason Pendrous in 2019 while he was living in student accommodation. During the COVID-19 restrictions, thousands of students were required to leave their tertiary student accommodation, however, some universities continued to charge students for unused rooms. A Parliamentary Inquiry was initiated after media reporting and advocacy of student associations, local and central Government politicians. However, these only addressed the student accommodations provided by tertiary education providers. Measures to improve tertiary students’ experiences of the private residential rental market remain largely absent, let alone any significant policy to address student energy poverty.

4.4. Limitations

This study was not representative of the entire student body in New Zealand. Instead, it aimed to provide a general overview of energy poverty among the student population. However, recruiting participants for the survey was complicated by our reliance on student associations and education providers to share the survey link, so the study has inherent self-selection bias. In addition, as the survey went live in December 2020, many student associations and education providers were closed for the year, and students would have been less likely to check their student emails over the initial holiday period. We do not believe that the use of the incentive of entering a prize draw to win one of five NZ

$50 supermarket gift cards would have unduly added to bias. Moreover, the survey questionnaire did not collect information that can identify part-time students. Students with disabilities are more likely to be studying part-time [

52]. The study found a significantly higher impact of energy poverty on students with disabilities and health concerns. Collecting information specific to part-time studies could have allowed a more comprehensive analysis.

4.5. Suggestions for Future Research

This study has identified several avenues for future research to better understand the experience of energy poverty among tertiary students in New Zealand and to provide a stronger evidence base for policy. The findings regarding students with disabilities or long-term health concerns make a compelling case that further research is urgently required to better understand the challenges these students face, and further classify the type of disability and energy poverty outcomes that would support policy development. To date, most energy poverty research in New Zealand has focused on the impacts of cold housing and winter energy poverty; however, it would be useful to understand the extent to which summer energy poverty is a problem, especially for groups at higher risk of energy poverty, including tertiary students. Other useful areas for future research would be to focus on which regulations result in the highest improvements in energy efficiency, energy poverty and student wellbeing.