Striving for Enterprise Sustainability through Supplier Development Process

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Supplier Development

2.2. Socially Responsible Supplier Development

3. Methodology

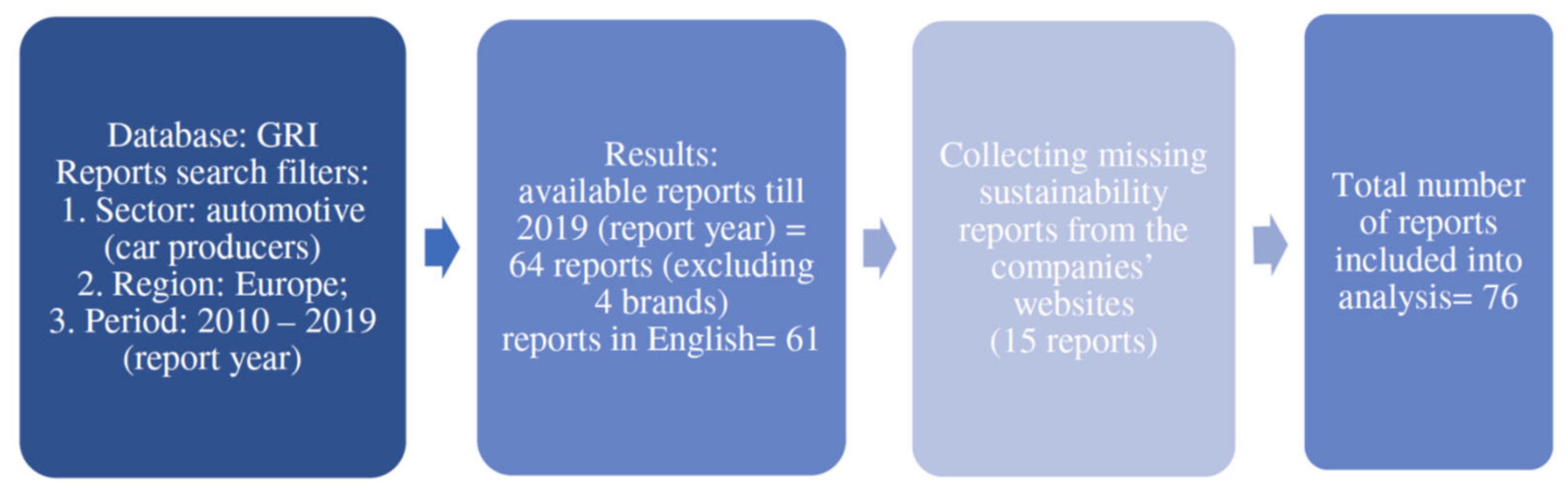

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Collection

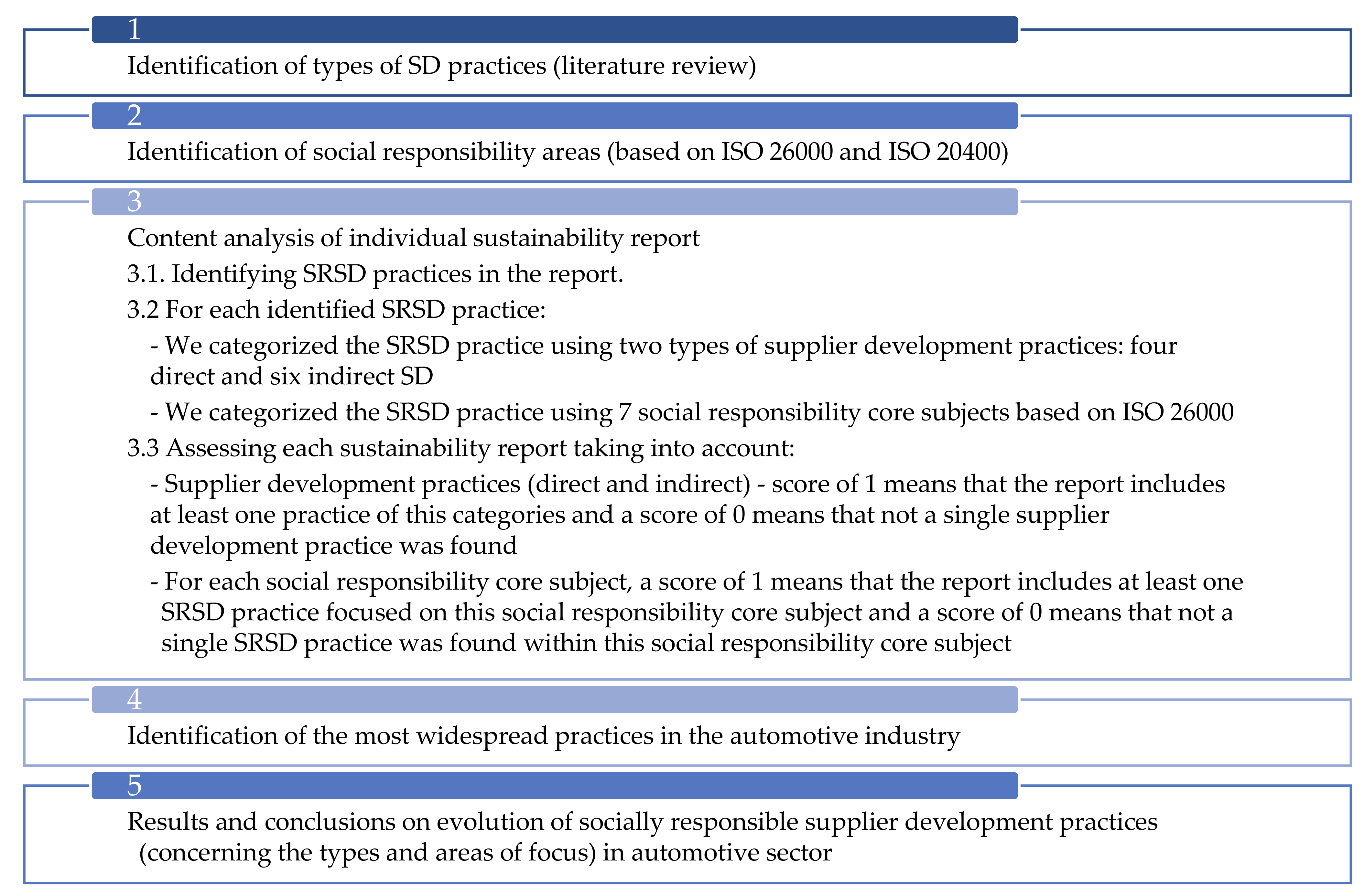

3.2. Content Analysis

4. Results

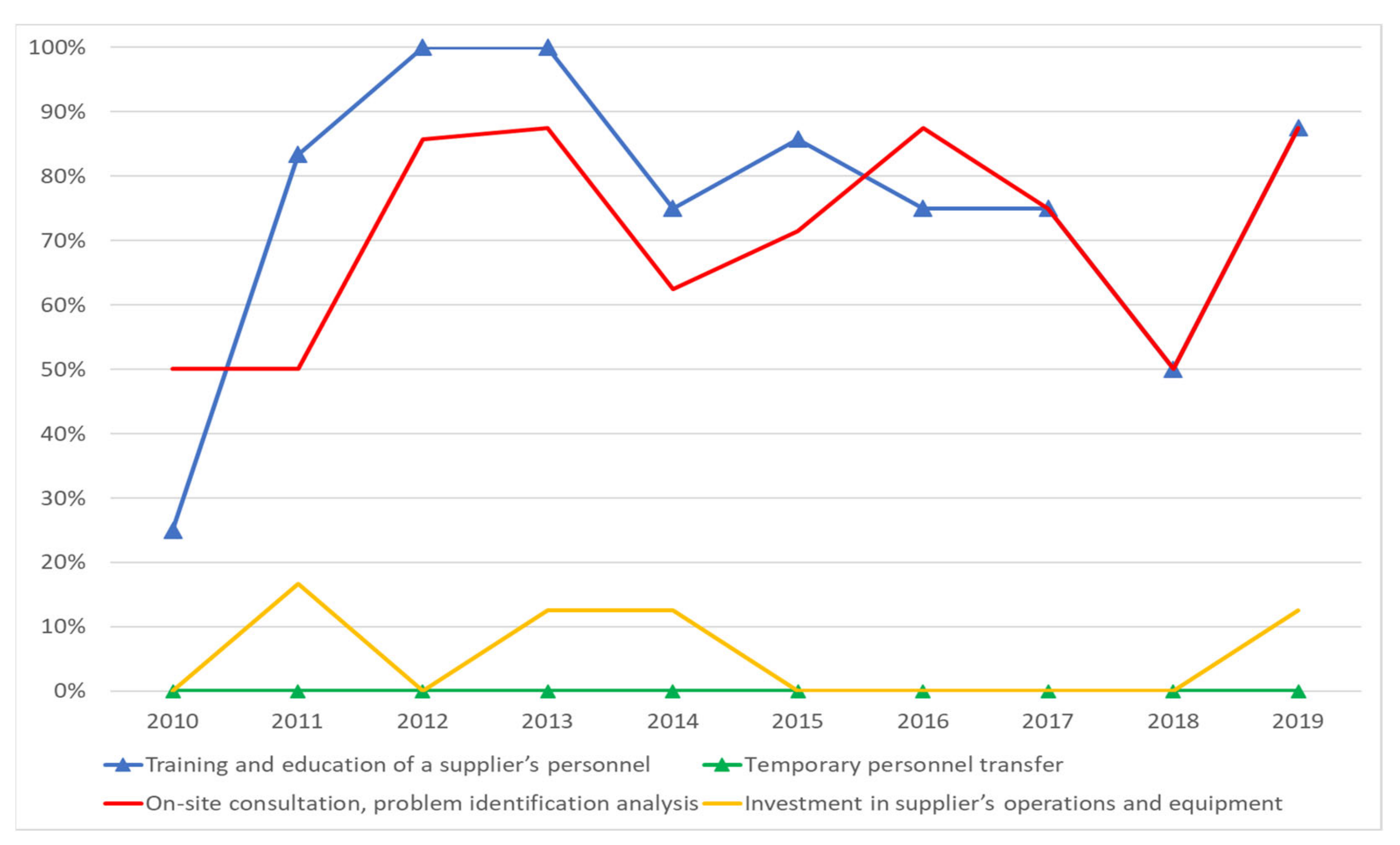

4.1. Direct Socially Responsible Supplier Development Practices

4.2. Indirect Socially Responsible SD Practice

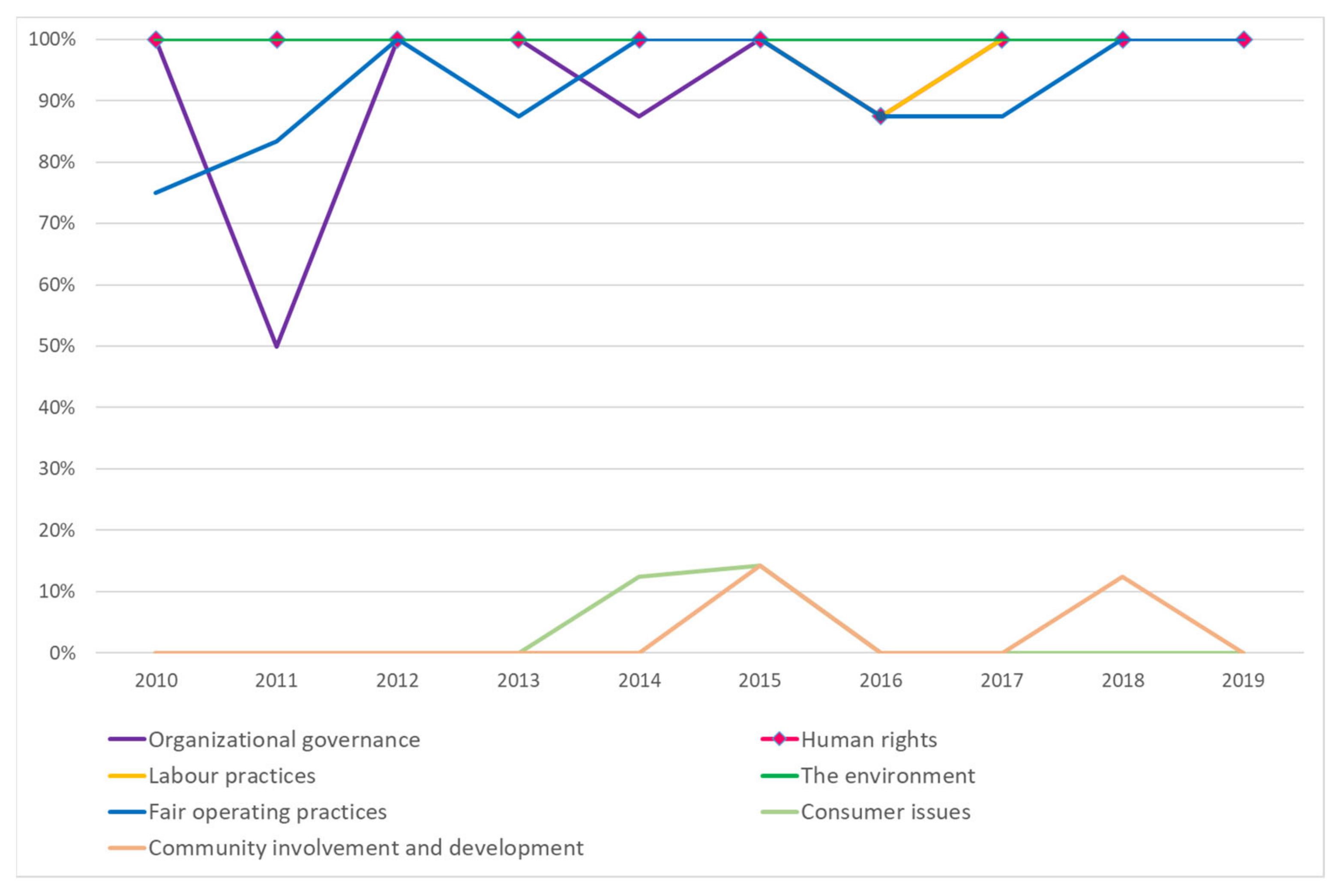

4.3. Socially Responsible Supplier Development Practices and SR Core Subjects

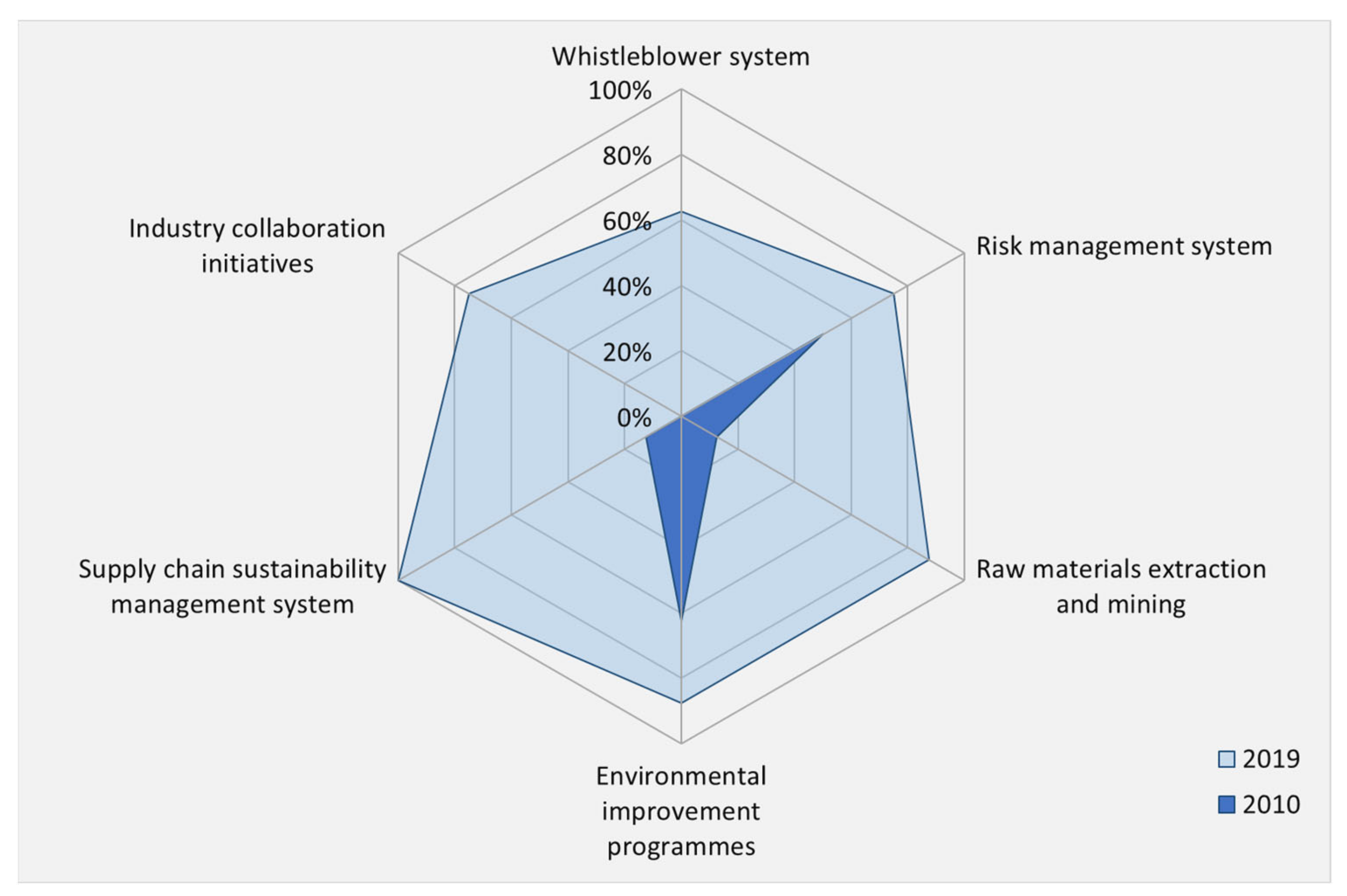

4.4. The Most Common SRSD Practices

- Risk management system;

- Whistle-blower system;

- Raw material extraction and mining;

- Environmental improvement programmes;

- Industry collaboration initiatives;

- Supply chain sustainability management system.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Janik, A.; Ryszko, A. Measuring Product Material Circularity—A Case of Automotive Industry. In Proceedings of the International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference Surveying Geology and Mining Ecology Management, SGEM; International Multidisciplinary Scientific Geoconference, Albena, Bulgaria, 29 June–5 July 2017; Volume 17, pp. 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonek-Kowalska, I.; Zieliński, M. CSR Activities in the Banking Sector in Poland. In Proceedings of the 29th International Business Information Management Association Conference—Education Excellence and Innovation Management through Vision 2020: From Regional Development Sustainability to Global Economic Growth, Vienna, Austria, 3–4 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cierna, H.; Sujová, E. Integrating Principles of Excellence and of Socially Responsible Entrepreneurship. Manag. Syst. Prod. Eng. 2020, 28, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gajdzik, B.; Grabowska, S.; Saniuk, S.; Wieczorek, T. Sustainable Development and Industry 4.0: A Bibliometric Analysis Identifying Key Scientific Problems of the Sustainable Industry 4.0. Energies 2020, 13, 4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasadzien, M. Social Evaluation of Mining Activity Effects. In Proceedings of the International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference Surveying Geology and Mining Ecology Management, SGEM, Albena, Bulgaria, 17–26 June 2014; Volume 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, H.; Hąbek, P.; Cierna, H. Corporate Social Responsibility and Self-Regulation. MM Sci. J. 2016, 2016, 1121–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluszcz, A. Conditions for Maintaining the Sustainable Development Level of EU Member States. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tokoro, N. Stakeholders and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): A New Perspective on the Structure of Relationships. Asian Bus. Manag. 2007, 6, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzior, A.; Ober, J.; Karwot, J. Stakeholder Expectation of Corporate Social Responsibility Practices: A Case Study of PWiK Rybnik, Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tworzydło, D.; Gawroński, S.; Szuba, P. Importance and role of CSR and stakeholder engagement strategy in polish companies in the context of activities of experts handling public relations. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.S.; Greenwood, C.A. Communicating corporate social responsibility (CSR): Stakeholder responsiveness and engagement strategy to achieve CSR goals. Public Relat. Rev. 2017, 43, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hąbek, P.; Biały, W.; Livenskaya, G. Stakeholder Engagement in Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting: The Case of Mining Companies. Acta Montan. Slovaca 2019, 24, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri, M.A. The Rationale for Responsible Supply Chain Management and Stakeholder Engagement. J. Glob. Responsib. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peloza, J.; Shang, J. How Can Corporate Social Responsibility Activities Create Value for Stakeholders? A Systematic Review. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy & Society: The Link between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavhan, R.; Mahajan, D.S.K.; Joshi Sarang, P. Supplier Development Success Factors in Iindian Manufacturing Practices. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habek, P.; Wolniak, R. Factors Influencing the Development of CSR Reporting Practices: Experts’ versus Preparers’ Points of View. Eng. Econ. 2015, 26, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rashidi, K.; Saen, R.F. Incorporating Dynamic Concept into Gradual Efficiency: Improving Suppliers in Sustainable Supplier Development. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 202, 226–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leenders, M.R. Supplier Development. J. Purch. 1966, 2, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, D.R.; Handfield, R.B.; Scannell, T.V. An Empirical Investigation of Supplier Development: Reactive and Strategic Processes. J. Oper. Manag. 1998, 17, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, D.R.; Scannell, T.V.; Calantone, R.J. A Structural Analysis of the Effectiveness of Buying Firms’ Strategies to Improve Supplier Performance. Decis. Sci. 2000, 31, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, P.; Cadden, T.; Li, W.L.; McHugh, M. An Investigation into Supplier Development Activities and Their Influence on Performance in the Chinese Electronics Industry. Prod. Plan. Control 2011, 22, 9152–9164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, D.R.; Ellram, L.M. Critical Elements of Supplier Development The Buying-Firm Perspective. Eur. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 1997, 3, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.M. A Firm’s Responses to Deficient Suppliers and Competitive Advantage. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.M. Supplier Development Practices: An Exploratory Study. Eur. J. Mark. 2006, 40, 554–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.M. Indirect and Direct Supplier Development: Performance Implications of Individual and Combined Effects. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2010, 57, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monczka, R.M.; Trent, R.J.; Callahan, T.J. Supply base strategies to maximize supplier performance. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manage. 1993, 23, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.M.; Krause, D.R. Supplier Development: Communication Approaches, Activities and Goals. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2009, 47, 3161–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Proch, M.; Worthmann, K.; Schlüchtermann, J. A Negotiation-Based Algorithm to Coordinate Supplier Development in Decentralized Supply Chains. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 256, 412–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Automotive Industry Action Group. IATF 16949:2016. Available online: https://www.aiag.org/quality/iatf16949/iatf-16949-2016 (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Lu, R.X.A.; Lee, P.K.C.; Cheng, T.C.E. Socially Responsible Supplier Development: Construct Development and Measurement Validation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancha, C.; Gimenez, C.; Sierra, V.; Kazeminia, A. Does Implementing Social Supplier Development Practices Pay Off? Supply Chain Manag. 2015, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumüller, C.; Lasch, R.; Kellner, F. Integrating Sustainability into Strategic Supplier Portfolio Selection. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.C. Effects of Socially Responsible Supplier Development and Sustainability-Oriented Innovation on Sustainable Development: Empirical Evidence from SMEs. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 661–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, H.; Busse, C.; Bode, C.; Henke, M. Sustainability-Related Supply Chain Risks: Conceptualization and Management. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2014, 23, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Yao, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, S. Socially Responsible Supplier Selection and Sustainable Supply Chain Development: A Combined Approach of Total Interpretive Structural Modeling and Fuzzy Analytic Network Process. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2018, 27, 1708–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorzini, M.; Hendry, L.C.; Huq, F.A.; Stevenson, M. Socially Responsible Sourcing: Reviewing the Literature and Its Use of Theory. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaysheh, A.; Klassen, R.D. The Impact of Supply Chain Structure on the Use of Supplier Socially Responsible Practices. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2010, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, P.L.; Iranmanesh, M.; Kumar, K.M.; Foroughi, B. The Impact of Multinational Corporations’ Socially Responsible Supplier Development Practices on Their Corporate Reputation and Financial Performance. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2020, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghababsheh, M.; Gallear, D. Socially Sustainable Supply Chain Management and Suppliers’ Social Performance: The Role of Social Capital. J. Bus. Ethics 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tundys, B. Sustainable Supply Chain Management—Past, Present and Future. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. Wrocławiu 2020, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, Z.N.; Kant, R. A State-of-Art Literature Review Reflecting 15 Years of Focus on Sustainable Supply Chain Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 2524–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, A.; Leat, M.; Hudson-Smith, M. Making Connections: A Review of Supply Chain Management and Sustainability Literature. Supply Chain Manag. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez, C.; Tachizawa, E.M. Extending Sustainability to Suppliers: A Systematic Literature Review. Supply Chain Manag. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancha, C.; Longoni, A.; Giménez, C. Sustainable Supplier Development Practices: Drivers and Enablers in a Global Context. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2015, 21, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yawar, S.A.; Seuring, S. The Role of Supplier Development in Managing Social and Societal Issues in Supply Chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yawar, S.A.; Kauppi, K. Understanding the Adoption of Socially Responsible Supplier Development Practices Using Institutional Theory: Dairy Supply Chains in India. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2018, 24, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, R.; Aitken, J. Selecting Suppliers for Socially Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Post-Exchange Supplier Development Activities as Pre-Selection Requirements. Prod. Plan. Control 2019, 30, 1184–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Taffler, R.J. A Content Analysis of Discretionary: The Chairman’s Statement. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2000, 13, 624–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vourvachis, P. On the Use of Content Analysis (CA) in Corporate Social Reporting (CSR): Revisiting the Debate on the Units of Analysis and the Ways to Define Them. In Proceedings of the British Accounting Association Annual Conference, Egham, UK, 3–5 April 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vourvachis, P.; Woodward, T. Content Analysis in Social and Environmental Reporting Research: Trends and Challenges. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2015, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krause, D.R. The antecedents of buying firms’ efforts to improve suppliers. J. Oper. Manag. 1999, 17, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Paper | Type of Research | Targeted Countries | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| [38] | Empirical analysis. Plant-level survey | Canada (three industries) | Four categories of suppliers’ socially responsible practices are identified and validated: 1. supplier human rights; 2. supplier labor practices; 3. supplier codes of conduct; 4. supplier social audit. The relationship between the drivers and the supplier’s socially responsible practices are explored. |

| [43] | Theoretical. A systematic review of current SCM literature | -- | Although two dimensions of supply chain sustainability, the social and environmental dimensions, are treated separately in the literature, there is a limited amount of research on how these dimensions can be integrated. |

| [44] | Structured literature review | -- | The analysis is focused on the impact of assessment and collaboration on the sustainable performance of the supply chain. The paper concludes that assessment is not enough to improve sustainability; some degree of collaboration among the firms is necessary. They provide a list of enablers to adopt a collaborative approach based on the supplier development model of Krause et al. (2000). |

| [31] | Both conceptual and empirical | China | The paper integrates the concepts of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and supplier development into the concept of socially responsible supplier development (SRSD). Additionally, the paper proposes an SRSD scale system to assess the level of supplier development of an organization. |

| [37] | Structured literature review | -- | The paper is state of the art in socially responsible sourcing (SRS). This concept includes human rights, community development, and ethical issues, but excludes environmental concerns. It provides a classification of the papers dealing with socially responsible sourcing based on the theories they use. |

| [32] | Empirical analysis. Literature review and survey | Spain | The paper investigates the impact of social supplier development practices on both suppliers social performance and economic and operational results, showing that it has a positive effect on the suppliers social performance and the operational performance of the buying firm, but economically they do not pay off. |

| [45] | Analytical model. Hierarchical linear modelling | International (22 countries) | The paper investigates the effect of different environmental factors on sustainable supplier development practices. The effect of three drivers, namely, coercive, normative, and mimetic pressures, and the firm’s capabilities and supplier integration are assessed. |

| [33] | Analytical. Case study | -- | The paper provides an analytical approach to supplier selection using both traditional performance objectives and sustainability-related aims. The authors used a hybrid model of the analytic network process (ANP) and goal programming (GP). |

| [34] | Empirical analysis. Literature review and survey | Taiwan | The paper combines the concepts of socially responsible supplier development with organizational innovation, focusing on SMEs. A measurement scale to assess supplier organizational innovation was developed to relate it to SRSD. The study provides practical managerial recommendations to improve the sustainability performance of SMEs. |

| [36] | Analytical. Case study | China | The paper proposes a hybrid analytical model to select the most appropriate supplier, including variables based on expert opinion, with a high degree of vagueness and ambiguity. The authors used a hybrid model that combines TISM and FANP. |

| [46] | Empirical. Case study | India | This paper explore the role of SD as an effective strategy in building the capabilities of addressing social issues. |

| [47] | Empirical. Case study | India | This study compares the economic and social variants of institutional theory to investigate whether efficiency or legitimacy seeking drives the adoption of supplier development practices. |

| [18] | Analytical model, applied to a case study | Iran | This study proposes a framework to evaluate and monitor suppliers continuously and divides the sustainable supplier development process into several subprocesses. By implementing this model, the buying firm identifies the source of inefficiencies in the supplier’s sustainability performance. |

| [39] | Empirical. Survey | Malaysia | By empirically testing the impacts of four proposed supplier development practices, supplier development and supplier collaboration have a significant impact on their social performance. |

| [48] | Empirical. Exploratory case study | UK | One major insight is that for socially responsible purchasing to occur, there are four main behaviors that suppliers need to demonstrate to buyers, namely, demonstrating trust, transparency, engagement, and a knowledge development capability. The authors suggest that socially responsible supplier development should be introduced early in the process of supplier selection, at a pre-selection stage rather than at the post-selection evaluation stage. |

| [40] | Empirical. Survey | UK | This study focus on the impact of assessment and collaboration on suppliers’ social performance and how these effects can be strengthened by the level of social capital embedded in the buyer–supplier relationship. Based on a survey of 119 manufacturing companies, the authors found that assessment practices are less likely to influence suppliers to improve social performance compared to collaboration practices, but can have a significant positive effect when relational and structural capital are manifested in the relationship. |

| Direct SD |

|---|

| 1. Training and education of a supplier’s personnel. A2Workshops and training organized and conducted by buyer (including e-learning). |

| 2. Temporary personnel transfer.A2Transfer of buyer personnel to the supplier to share knowledge, improve supplier capabilities, provide technical support etc. |

| 3. On-site consultation, problem identification analysis. A2Buyer helps directly to resolve the supplier’s problem (on-site consultation, problem identification, analysis of the causes, finding solutions etc.). |

| 4. Investment in supplier’s operations and equipment./ A2Financial investment related to improving product or processes, to finance tools or equipment needed to manufacture the buying firm’s products. |

| Indirect SD |

| 1. Self-regulation. A2Supplier’s code of conduct, setting standards and rules for cooperation. |

| 2. Information sharing. A2Supplier days, communication of the firm’s strategic targets to suppliers, supplier plant visits. |

| 3. Supplier evaluation. A2Regular, planned, and proactive measurements of supplier performance. |

| 4. Supplier selection. A2First step in supplier development, setting selection criteria, ranking the suppliers (for further strategic supplier development). |

| 5. Supplier auditing. A2Checking if suppliers are able to fulfil buyer’s specific requirements, certification, ensuring that the supplier undertakes continuous improvement and operates efficiently. |

| 6. Supplier recognition, rewards.A2Encourage improved results and reward performance; reward suppliers for outstanding performance, further motivating quality and encouraging suppliers to strive for excellence in their products, service levels, and operations. |

| Social Responsibility Subjects and Issues | |

|---|---|

| 1. Organizational governance Decision-making processes and structures | |

| 2. Human rights Due diligence Human rights risk situations Avoidance of complicity Resolving grievances Discrimination and vulnerable groups Civil and political rights Economic, social, and cultural rights Fundamental principles and rights at work | 5. Fair operating practices Anti-corruption Responsible political involvement Fair competition Promoting social responsibility in the value chain Respect for property rights |

| 3. Labor practices Employment and employment relationships Conditions of work and social protection Social dialogue Health and safety at work Human development and training in the workplace | 6. Consumer issues Fair marketing, factual and unbiased information, and fair contractual practices Protecting consumers’ health and safety Sustainable consumption Consumer service, support, and complaint and dispute resolution Consumer data protection and privacyAccess to essential services Education and awareness |

| 4. Environment Prevention of pollution Sustainable resource use Climate change mitigation and adaptation Protection of the environment, biodiversity, and restoration of natural habitats | 7. Community involvement and development Community involvement Education and culture Employment creation and skills development Technology development and access Wealth and income creation Health Social investment |

| Reported Year | BMW Group | Daimler | FCA | Jaguar Land Rover | PSA | Renault | Volkswagen AG | Volvo Group | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | 8 |

| 2011 | GRI | GRI | GRI | Non-GRI | GRI | GRI | 6 | ||

| 2012 | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | Non-GRI | GRI | GRI | 7 | |

| 2013 | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | 8 |

| 2014 | GRI | GRI | GRI | Non-GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | 8 |

| 2015 | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | 7 | |

| 2016 | GRI | GRI | GRI | Non-GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | 8 |

| 2017 | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | 8 |

| 2018 | GRI | GRI | GRI | Non-GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | 8 |

| 2019 | GRI | GRI | GRI | Non-GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | GRI | 8 |

| Total | 9 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 76 |

| Year | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 8 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Training and education of supplier’s personnel | 25% | 83% | 100% | 100% | 75% | 86% | 75% | 75% | 50% | 88% |

| Temporary personnel transfer | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| On-site consultation, problem identification | 50% | 50% | 86% | 88% | 63% | 71% | 88% | 75% | 50% | 88% |

| Investment in supplier’s operations and equipment | 0% | 17% | 0% | 13% | 13% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 13% |

| Year | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 8 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Self-regulation | 88% | 67% | 100% | 100% | 88% | 86% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Information sharing | 88% | 83% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 88% | 88% | 88% | 100% |

| Supplier evaluation | 100% | 83% | 86% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 88% | 100% |

| Supplier selection | 50% | 33% | 43% | 38% | 50% | 71% | 38% | 75% | 50% | 75% |

| Supplier auditing | 75% | 67% | 86% | 100% | 88% | 100% | 88% | 88% | 88% | 100% |

| Suppl. recognition, rewards | 13% | 17% | 57% | 38% | 50% | 57% | 63% | 63% | 50% | 63% |

| Year | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size º | 8 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Organizational governance | 83% | 50% | 100% | 100% | 88% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Human rights | 83% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 88% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Labor practices | 83% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 88% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| The environment | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Fair operating practices | 50% | 83% | 100% | 88% | 100% | 100% | 88% | 88% | 100% | 100% |

| Consumer issues | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 13% | 14% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Community involvement and development | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 14% | 0% | 0% | 13% | 0% |

| BMW | The BMW risk management system is based on OECD Due Diligence Guidance. |

| Daimler | Daimler has developed a due diligence approach called the Daimler Human Rights Respect System (HRRS) to protect the human rights of employees and to ensure that human rights are respected by the suppliers (Tier 1 and risk-relevant points of the supply chain beyond Tier 1). |

| FCA | FCA assesses the supplier’s overall sustainability risk level using a risk map, which is used to prioritize supplier audits. These audits identify areas of improvement for suppliers. |

| PSA | PSA uses risk analysis (mapping) to identify and prioritize actual or potential incidents in the supply chain. Where risk is identified, Groupe PSA has a prevention system to implement and monitor specific action plans with involved suppliers to prevent or mitigate any impact to the supply chain. |

| Renault | Supplier risk monitoring of operations, finances, and CSR (in particular health/safety, social and environmental risks). Suppliers’ CSR risks may be identified through risk mapping of specific risks, supplemented by an annual audit program. |

| Volkswagen | Business partners identified as having an increased corruption risk due to their business and region are also subjected to an in-depth audit. Particular attention is paid to human risks abuses. They follow the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains. |

| Volvo | According to the risk assessment tool, Volvo analyzes suppliers based on sustainability assessments to ensure awareness of potential risks and to prioritize them. The Responsible Business Alliance, an industry coalition dedicated to corporate social responsibility in global supply chains, developed this tool. |

| BMW | Action taken on selected raw materials: aluminum, cobalt, lithium, copper, or natural rubber. |

| Daimler | Daimler has identified 24 raw materials and 27 services whose extraction and further processing/provision (services) pose potential risks to human rights, e.g., they focus on raw materials such as cobalt, mica, or natural rubber. The “Responsible Aluminium Standard” combines ethical, environmental, and social aspects. |

| FCA | Traceability and mapping of raw materials are essential to more efficiently and pre-emptively mitigate unethical practices that threaten the future of the communities where the raw materials are sourced. |

| PSA | Material risk mapping has been developed in terms, among others, of questionable CSR conditions (e.g., conflict minerals, mica, cobalt). They also focus on conflict minerals such as gold, tin, tantalum, and tungsten, which can be related to unethical behaviour. They joined the Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI). |

| Renault | Renault is a member of the Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI). The RMI’s objective is to implement a responsible supply chain for minerals and materials originating from conflict zones or high-risk areas. |

| Volkswagen | Concerning the conflict minerals tin, tantalum, tungsten, and gold, they require their suppliers to exclude the use of minerals from smelters not certified in accordance with international standards. They seek cooperation with international organizations, e.g., they use the Risk Readiness Assessment (RRA) and standardized reporting templates of the Responsible Minerals Initiative. The Volkswagen Group joined the Responsible Sourcing Blockchain Network (RSBN) for the responsible sourcing of strategic minerals using blockchain technology. |

| Volvo | Volvo Group is working with RMI to ensure responsible and sustainable sourcing of tin, tantalum, tungsten, and gold (the so-called conflict minerals), as well as cobalt, implementing the tools and guidelines developed by the RMI, such as reporting templates, to create supply chain transparency and RMI compliance of suppliers in the affected supply chains. |

| BMW | Encouraging suppliers to report their CO2 emissions in the CDP Supply Chain Programme. |

| Daimler | They promote CDP to assess the environmental impact of the passenger car supply chain. Additionally, they cooperate closely with their most CO₂-intensive suppliers to also identify effective CO₂ reduction measures in this area. |

| FCA | FCA promotes awareness among suppliers of their impact on climate change. Suppliers are invited to participate in the CDP Supply Chain program. |

| Jaguar Land Rover | Jaguar Land Rover collaborate with suppliers in different projects, e.g., to reach a closed-loop aluminum production, or reduction of the excessive consumption of single-use plastic. |

| PSA | PSA involves its core and strategic suppliers in a disruptive innovation process. PSA is member of CDP. They also set ambitious targets for suppliers regarding the percentage of green/recyclable materials. It has organized an upstream and downstream network to promote environmental improvements through the supply chain. |

| Renault | They implement environmental management company-wide and across the value chain in order to ensure continuous improvement and compliance with regulations and voluntary commitments. |

| Volkswagen | In 2019, the Volkswagen Group significantly expanded the number of suppliers who they survey as part of the SCP regarding responsibility for our climate and water. They implement other CO2 reduction initiatives, e.g., having found that the biggest driver of emissions in the supply chain for electric mobility is the HV battery cell, they implemented compulsory use of renewable energy sources in the manufacture of batteries by suppliers. |

| Volvo | The Volvo Group is continuously working towards optimizing its supplier base and geographical footprint. An optimized global footprint will reduce lead-time for the customers and actively reduce the CO2 footprint. |

| BMW | BMW is involved in Drive Sustainability and the Responsible Business Alliance (RBA), as well as subsidiary organization, the Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI), the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA) to foster transparency in mineral supply chains through their membership and other raw material-specific initiatives. |

| Daimler | Daimler participates in automotive industry initiatives such as the Drive Sustainability Initiative, the German Association of the Automotive Industry (VDA), as well as in cross-industry international initiatives such as the UN Global Compact and groups of national sustainability initiatives such as “econsense—Forum Nachhaltige Entwicklung der Deutschen Wirtschaft e.V.” |

| FCA | FCA fosters dialogue with the supply base by working closely with many industry and supplier organizations, including the Automotive Industry Action Group (AIAG). |

| Volkswagen | To avoid duplication and broader coverage of the supply chain, they are involved in automotive industry initiatives, such as the German Association of the Automotive Industry (VDA) or DRIVE Sustainability. |

| Volvo | Volvo is active in several working groups within the CSR Europe DRIVE Sustainability to develop assessment questionnaires for suppliers (SAQ) and broaden the awareness of sustainability topics in the industry and supply chain. |

| BMW | Carmaker’s internal system. |

| Daimler | Carmaker’s internal system. |

| FCA | World Class Manufacturing System (WCM), an integrated manufacturing system (including Environment and Health and Safety among its basic pillars). FCA specialists continued providing WCM methodology and tools to suppliers. |

| Jaguar Land Rover | Suppliers submit their sustainability performance measures to the Achilles data management system. Achilles collects and validates supplier data and mitigates risks globally. |

| PSA | Their responsible procurement policy includes a third-party assessment (by Ecovadis) of its suppliers based on CSR criteria. |

| Renault | They implement environmental management company-wide and across the value chain to ensure continuous improvement and compliance with regulations and voluntary commitments. |

| Volkswagen | Volkswagen have implemented their own sustainability management system in supplier relations, comprising three stages: prevent, detect, and react. |

| Volvo | Volvo’s Sustainable Purchasing Program looks at specific high risks to people and the environment and includes the following parts: Supplier Code of Conduct to create the right mindset; The Supplier Sustainability Assessment Program; Supply Chain Mapping; Innovation focusing on people and the planet including industry collaboration. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hąbek, P.; Lavios, J.J. Striving for Enterprise Sustainability through Supplier Development Process. Energies 2021, 14, 6256. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14196256

Hąbek P, Lavios JJ. Striving for Enterprise Sustainability through Supplier Development Process. Energies. 2021; 14(19):6256. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14196256

Chicago/Turabian StyleHąbek, Patrycja, and Juan J. Lavios. 2021. "Striving for Enterprise Sustainability through Supplier Development Process" Energies 14, no. 19: 6256. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14196256

APA StyleHąbek, P., & Lavios, J. J. (2021). Striving for Enterprise Sustainability through Supplier Development Process. Energies, 14(19), 6256. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14196256