The Transition to Clean Energy: Are People Living in Island Communities Ready for Smart Grids and Demand Response?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Elements of Smart Grid Readiness: Technical, Economic and Social Considerations

2.1. Technical Requirements for Householder Readiness to Take Part in Smart Grids and Demand Response

2.2. Motivation to Take Part in the Smart Grid and Demand Response

2.2.1. Economic Motivations

2.2.2. Attitudes and Social Norms

2.2.3. Knowledge and Familiarity with SG

2.3. Flexible Energy Demand

3. Methods

3.1. Survey Design and Distribution

3.1.1. Sample Size

3.1.2. Sample Representativeness

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

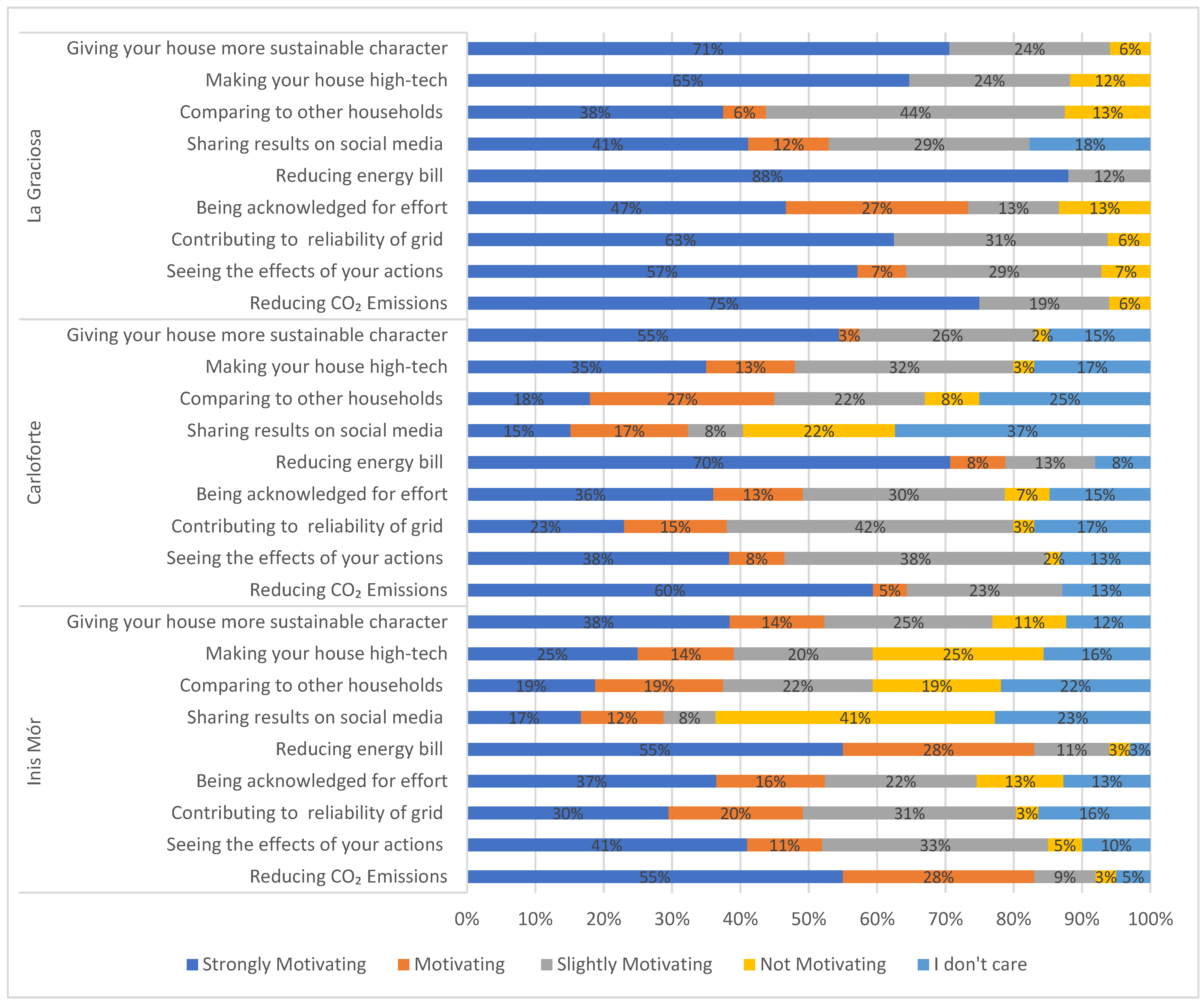

4.1. Motivations to Take Part in Demand Response and the Smart Grid

4.2. Readiness to Take Part in Demand Response and the Smart Grid

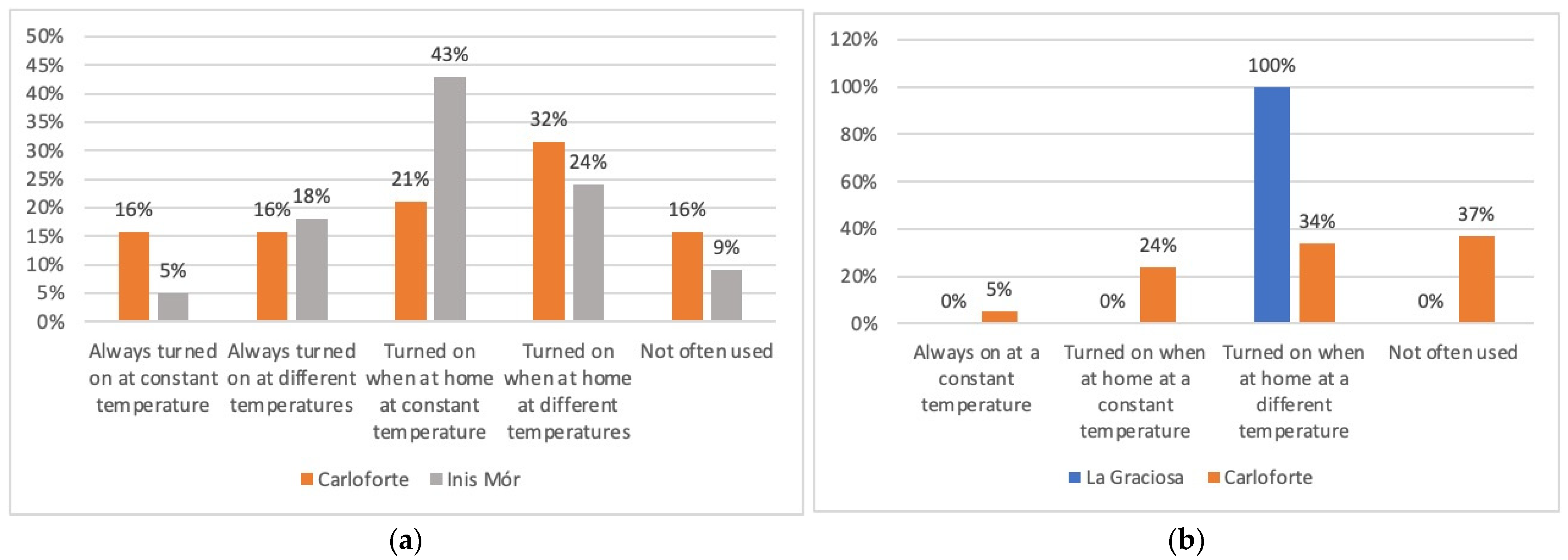

4.2.1. Household Heating and Cooling Systems

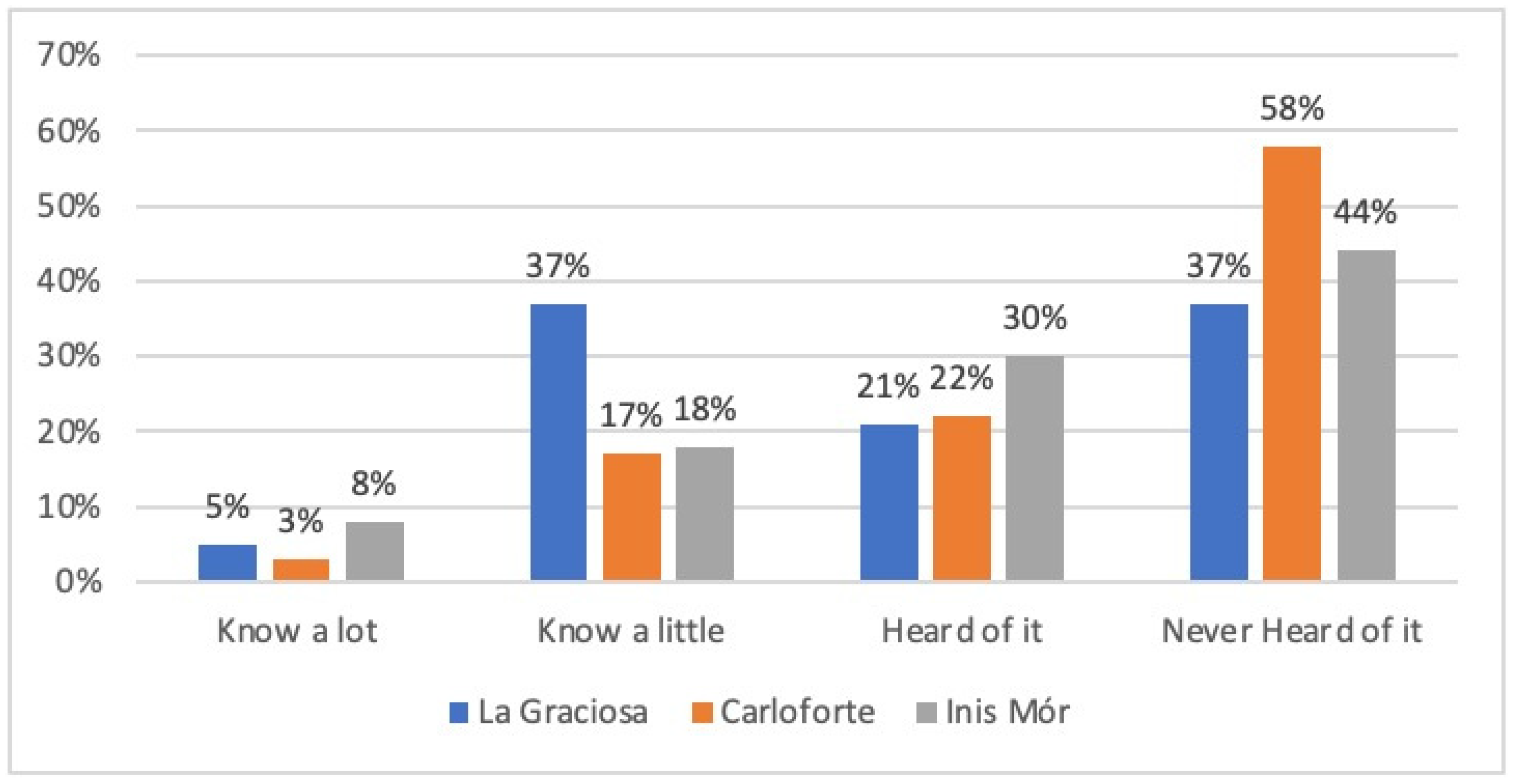

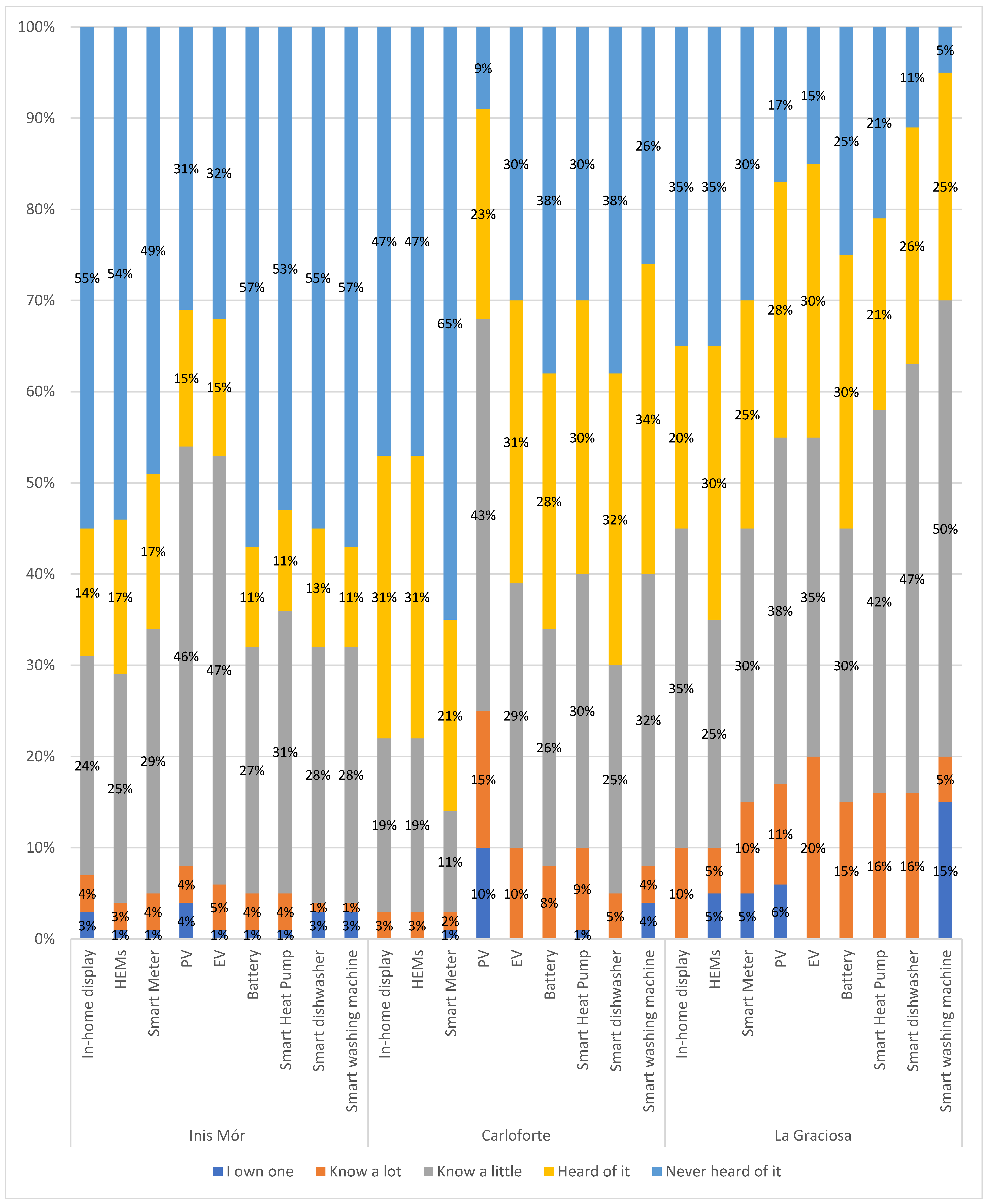

4.2.2. Familiarity with Smart Grids and Demand Response and Their Enabling Technologies

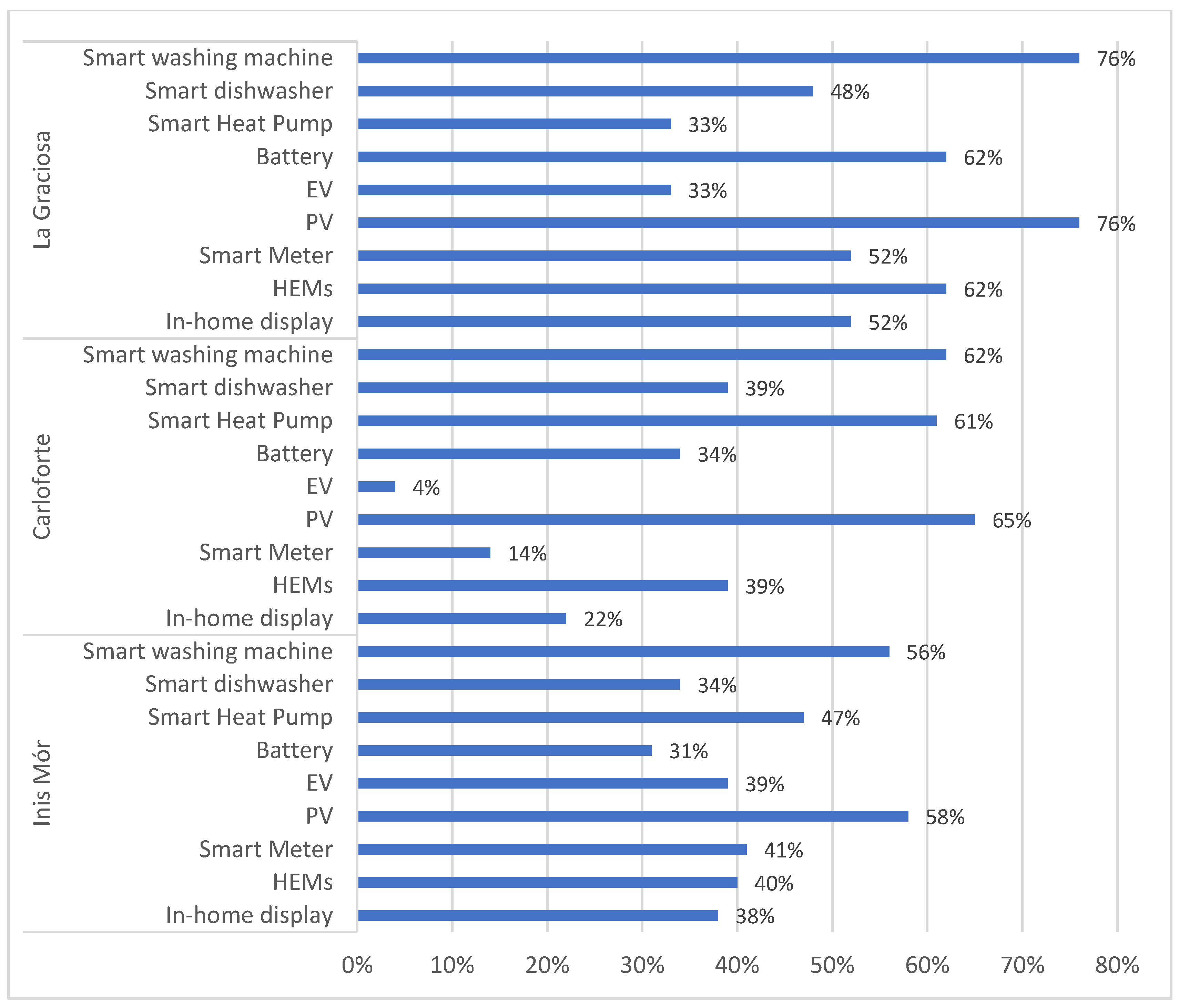

4.2.3. Respondents’ Willingness to Adopt SG Enabling Technologies

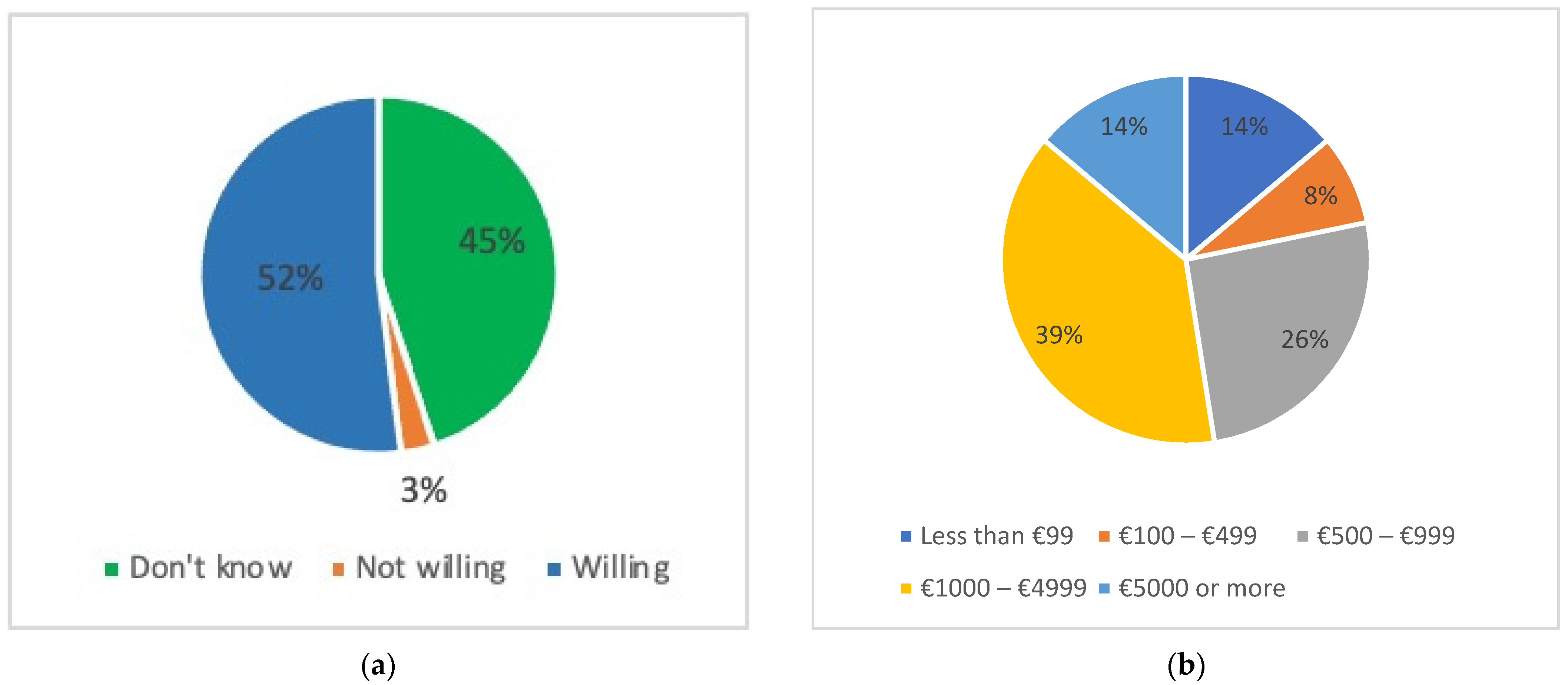

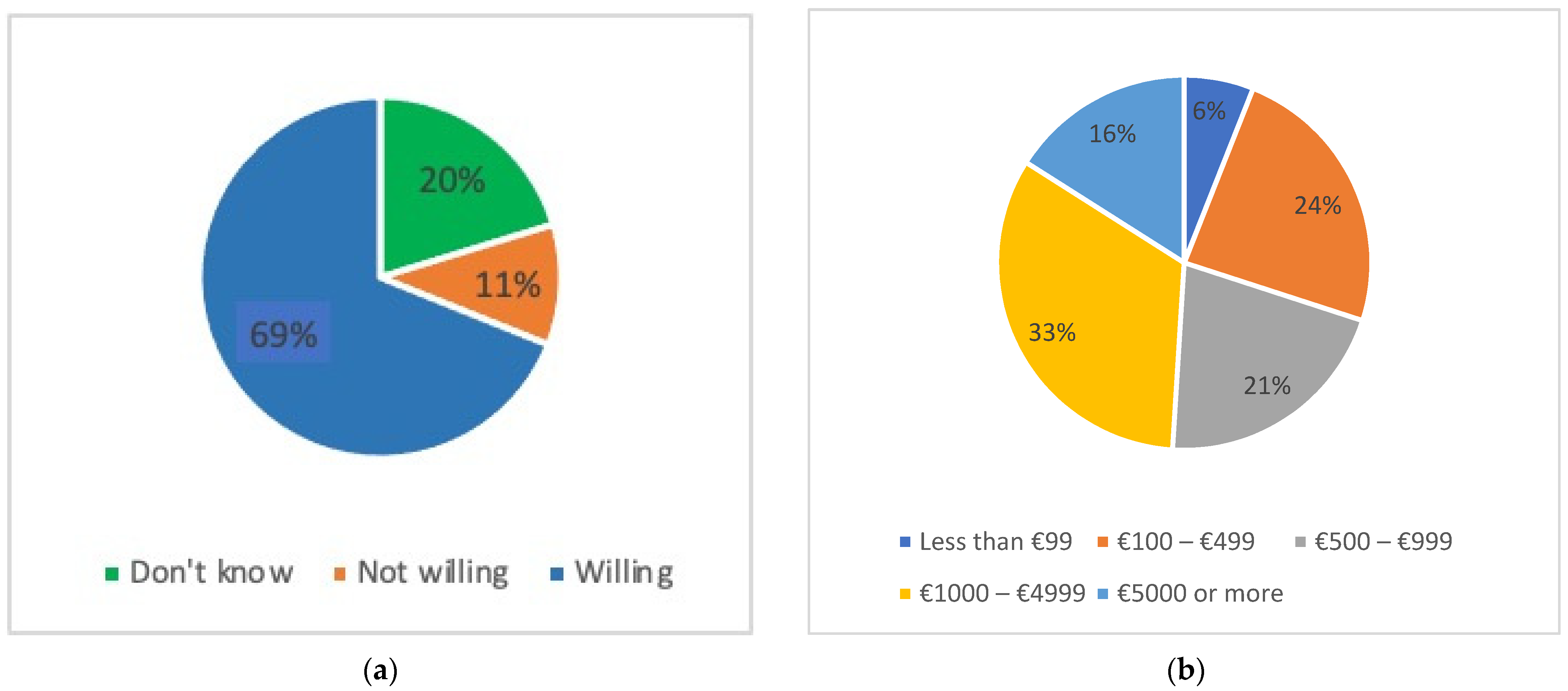

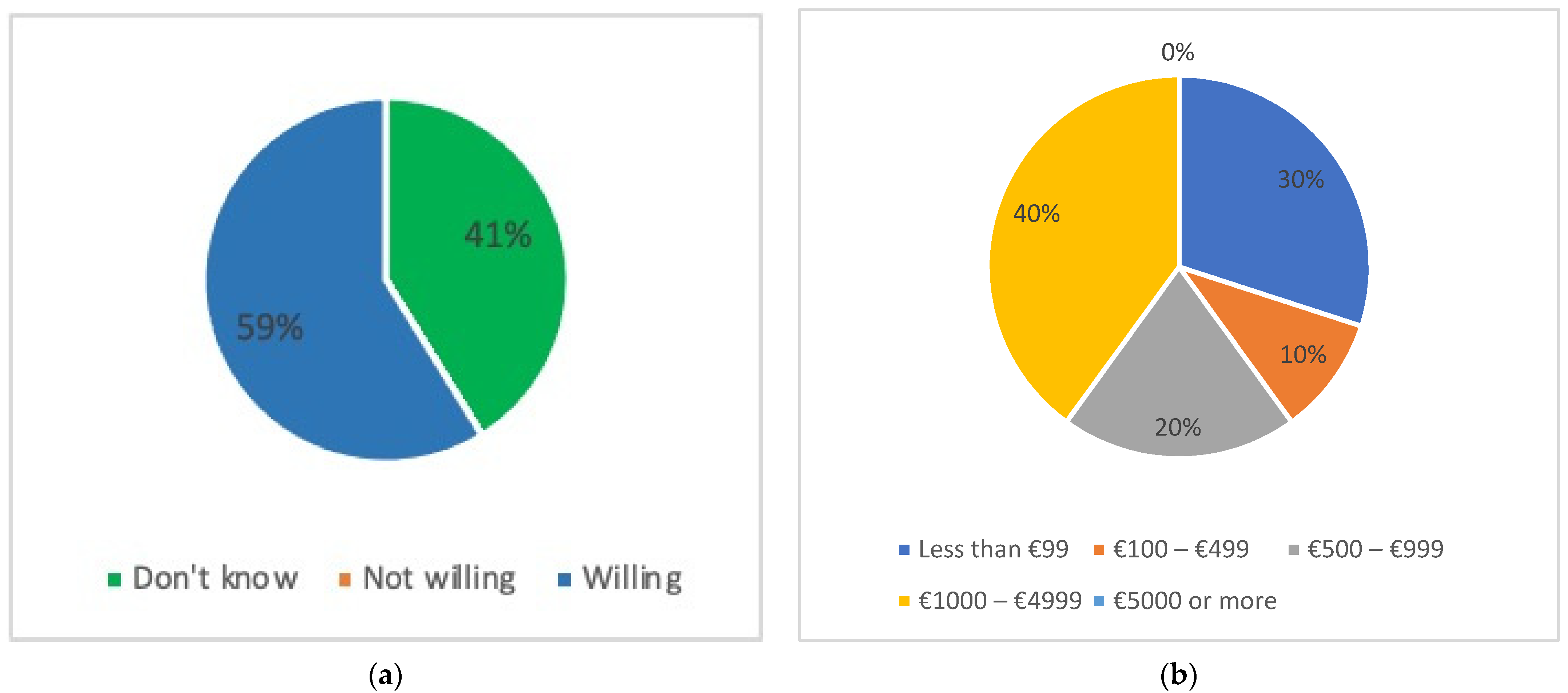

4.2.4. Willingness to Invest in Smart and Renewable Energy Technologies

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Aspects | Survey Questions |

|---|---|

| Demographic, household and building characteristics | Age; gender; household size; age of household members; education level (primary, secondary, technical training/education, university, postgraduate); employment (student, part-time work, full-time work, self-employed, unemployed, retired); type of dwelling (detached, semi-detached, row house, apartment in building, shared house); number of bedrooms. |

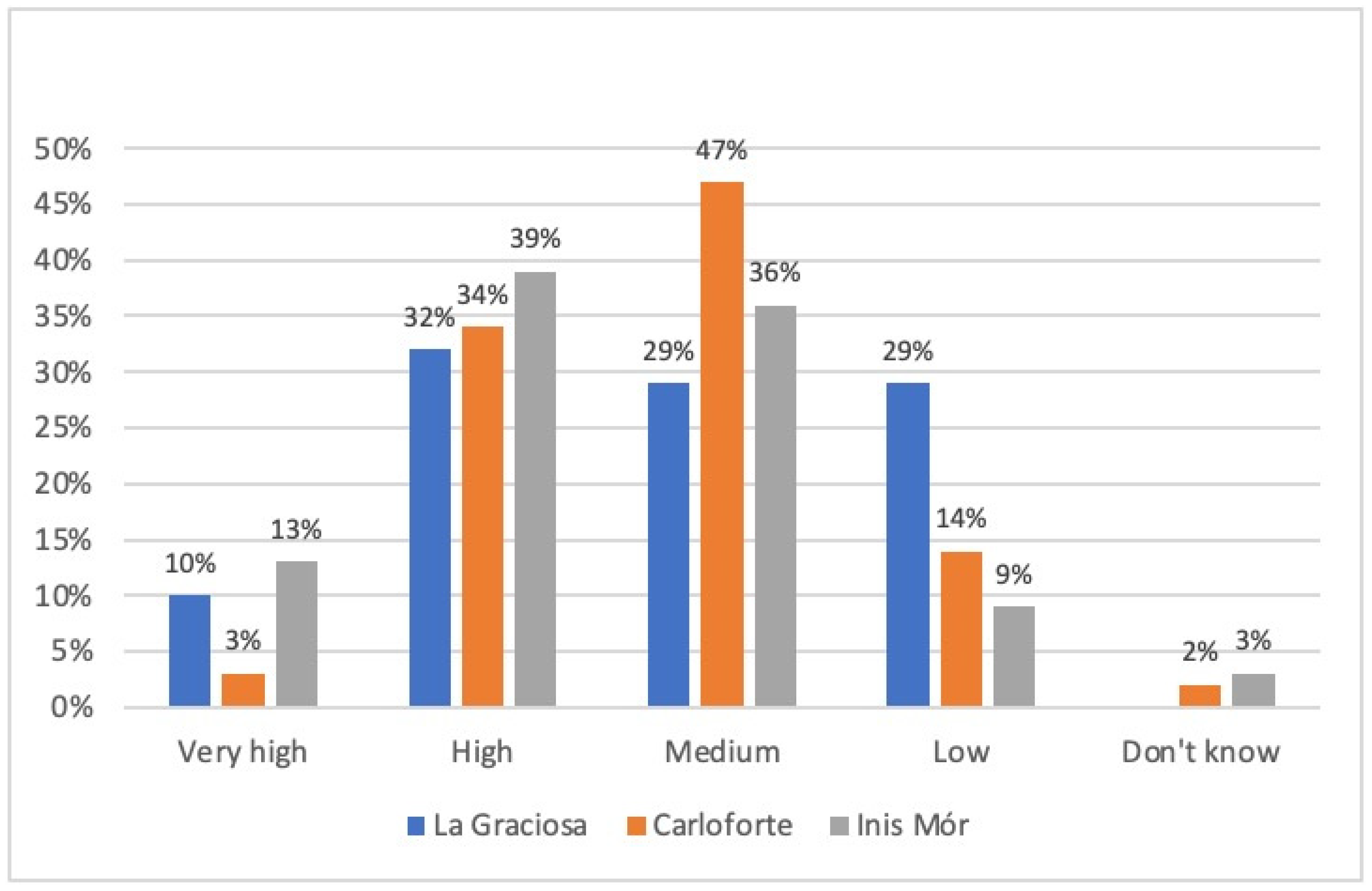

| Energy consumption and impact on household | impact of energy bill on household budget (very high impact, high impact, medium impact, low impact, no impact, Don’t know), average household energy bill (€50 or less, €50–€100, €100–€150, €150–€200, €200 or more, I don’t know), heating and air-conditioning systems: type (central, individual units, both, Don’t know); rooms heated; method of use (always on at constant temperature, always on at varied temperatures, turned on when someone is at home at constant temperature, turned on only when someone is at home in varied temperatures, Not often used); thermostat availability). |

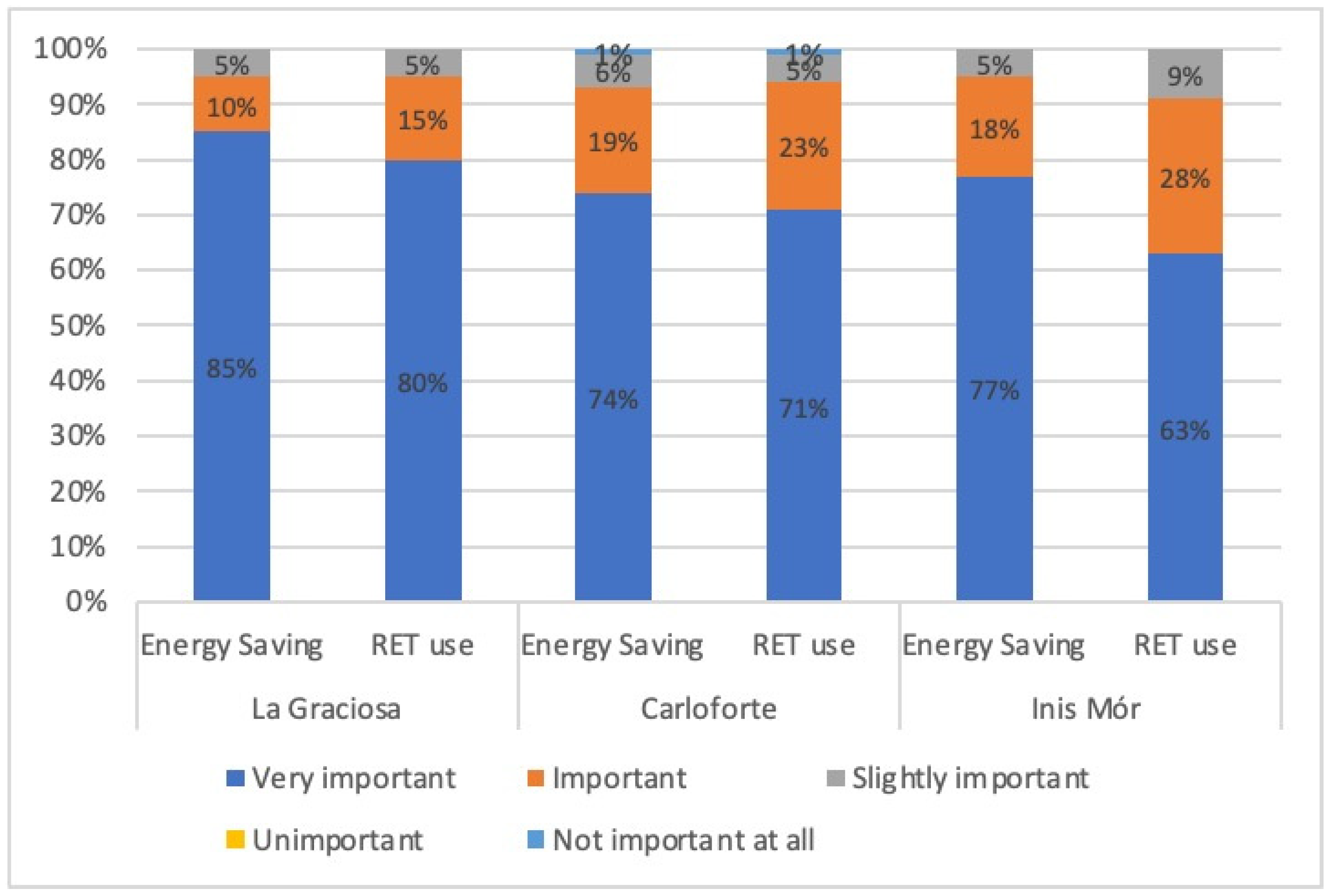

| Energy attitudes | Importance of energy saving (very important, important, slightly important, not important, not important at all); having RETs (very important, important, slightly important, not important, not important at all) |

| Familiarity with SG and DR | How familiar are you with the SG concept before contact by REACT? (never heard of it, heard a little of it but don’t understand the concept, heard a lot of it but don’t understand the concept, know a little about the concept, know a lot about the concept); How familiar are you with the following SG technologies and appliances? (smart washing machine, smart tumble dryer, smart dishwasher, smart refrigerator/freezer, smart heat pump, hot water storage tank with smart charging and discharging, battery with smart charging and discharging, electric vehicle, pv, micro co-generation (micro combined heat and power), smart meter, home energy management system, home energy display. Possible answers: never heard of it, heard of it but do not understand the concept, know a little about the concept, know a lot about the concept, I own one. |

| Willingness to adopt SG technologies | Which of the following would you like to use in your house? Smart washing machine, smart tumble dryer, smart dishwasher, smart refrigerator/freezer, smart heat pump, hot water storage tank with smart charging and discharging, battery with smart charging and discharging, electric vehicle, pv, micro co-generation (micro combined heat and power), smart meter, home energy management system, home energy display |

| Motivating factors | Which of the following measures can motivate you to accept smart grids and use smart appliances?—Giving your house a more sustainable character, making your house high-tech, comparing your energy consumption to other households, sharing your results on social media, reducing your energy bill, contributing to the reliability of the grid, receiving acknowledgement for efforts, seeing the effects of your actions, reducing your CO2 levels—(strongly motivating, motivating, slightly motivating, not motivating, I don’t care). |

| Willingness to pay for SG technologies | How much would you be willing to invest for installing RETs or SG enabling technologies?—(€99 or less, €100–€499, €500–€999, €1000–€4999, €5000 or more, Don’t know, I’m not willing to invest any money) |

References

- Edenhofer, O.; Pichs-Madruga, R.; Sokona, Y.; Seyboth, K.; Kadner, S.; Zwickel, T.; Eickemeier, P.; Hansen, G.; Schlömer, S.; von Stechow, C.; et al. (Eds.) Renewable Energy Sources and Climate Change Mitigation: Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, M.Z.; Delucchi, M.A.; Bauer, Z.A.F.; Goodman, S.C.; Chapman, W.E.; Cameron, M.A.; Bozonnat, C.; Chobadi, L.; Clonts, H.A.; Enevoldsen, P.; et al. 100% Clean and Renewable Wind, Water, and Sunlight All-Sector Energy Roadmaps for 139 Countries of the World. Joule 2017, 1, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muench, S.; Thuss, S.; Guenther, E. What hampers energy system transformations? The case of smart grids. Energy Policy 2014, 73, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissner, M. The Smart Grid—A saucerful of secrets? Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 2509–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, H. The promise of smart grids. Local Environ. 2019, 24, 580–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyberg, P.; Palm, J. Influencing households’ energy behaviour-how is this done and on what premises? Energy Policy 2009, 37, 2807–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. A Path to Prosperity: Renewable Energy for Islands; International Renewable Energy Agency: Bonn, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Smart Islands Initiative. Smart Islands Declaration: New Pathways for European Islands; Smart Islands Initiative. Available online: www.smartislandsinitiative.eu (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Stephanides, P.; Chalvatzis, K.J.; Li, X.; Lettice, F.; Guan, D.; Ioannidis, A.; Zafirakis, D.; Papapostolou, C. The social perspective on island energy transitions: Evidence from the Aegean archipelago. Appl. Energy 2019, 255, 113725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigrist, L.; Lobato, E.; Rouco, L.; Gazzino, M.; Cantu, M. Economic assessment of smart grid initiatives for island power systems. Appl. Energy 2017, 189, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, H.; Hann, V.; Watson, P. Rural laboratories and experiment at the fringes: A case study of a smart grid on Bruny Island, Australia. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 36, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelić, M.; Batić, M.; Tomašević, N.; Barney, A.; Polatidis, H.; Crosbie, T.; Ghanem, A.D.; Short, M.; Pillai, G. Towards Self-Sustainable Island Grids through Optimal Utilization of Renewable Energy Potential and Community Engagement. Energies 2020, 13, 3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjølsvold, T.M.; Ryghaug, M.; Throndsen, W. European island imaginaries: Examining the actors, innovations, and renewable energy transitions of 8 islands. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 65, 101491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorotić, H.; Doračić, B.; Dobravec, V.; Pukšec, T.; Krajačić, G.; Duić, N. Integration of transport and energy sectors in island communities with 100% intermittent renewable energy sources. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 99, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duić, N.; da Graça Carvalho, M. Increasing renewable energy sources in island energy supply: Case study Porto Santo. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2004, 8, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdinc, O.; Paterakis, N.G.; Catalaõ, J.P.S. Overview of insular power systems under increasing penetration of renewable energy sources: Opportunities and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 52, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, B.; Li, C.; Cao, Y.; Li, L.; Zeng, L. A review of renewable energy utilization in islands. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 59, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notton, G. Importance of islands in renewable energy production and storage: The situation of the French islands. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyström, S.; Rivera, M.B.; Hedin, B.; Katzeff, C.; Menon, A.R. Challenging the image of the altruistic and flexible household in the smart grid using design fiction. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Computing within Limits, 14–15 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado, E. Final Report: Energy in the EU Outermost Regions (Renewable Energy, Energy Efficiency); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Euroepan Commission. The Clean Energy for EU Islands Secretariat. Available online: https://euislands.eu/ (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- de Lesdain, B.S. The photovoltaic installation process and the behaviour of photovoltaic producers in insular contexts: The French island example (Corsica, Reunion Island, Guadeloupe). Energy Effic. 2019, 12, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, P.; Vine, D.; Buys, L. Critical Success Factors for Peak Electricity Demand Reduction: Insights from a Successful Intervention in a Small Island Community. J. Consum. Policy 2018, 41, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. Making sense of renewable energy: Practical knowledge, sensory feedback and household understandings in a Scottish island microgrid. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 66, 101501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J. Citizenship and sustainability in dependent island communities: The case of the Huon Valley region in southern Tasmania. Local Environ. 2003, 8, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackelworth, P.H.; Caric, H. Gatekeepers of island communities: Exploring the pillars of sustainable development. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2010, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REACT. Renewable Energy for Self-Sustainable Island Communities. Available online: https://react2020.eu/ (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Verbong, G.P.J.; Beemsterboer, S.; Sengers, F. Smart grids or smart users? Involving users in developing a low carbon electricity economy. Energy Policy 2013, 52, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosbie, T.; Baker, K. Energy-efficiency interventions in housing: Learning from the inhabitants. Build. Res. Inf. 2010, 38, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wall, R.; Crosbie, T. Potential for reducing electricity demand for lighting in households: An exploratory socio-technical study. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 1021–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosbie, T.; Short, M.; Dawood, M.; Charlesworth, R. Demand response in blocks of buildings: Opportunities and requirements. Int. J. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2017, 4, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meyers, R.J.; Williams, E.D.; Matthews, H.S. Scoping the potential of monitoring and control technologies to reduce energy use in homes. Energy Build. 2010, 42, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotouhi Ghazvini, M.A.; Soares, J.; Abrishambaf, O.; Castro, R.; Vale, Z. Demand response implementation in smart households. Energy Build. 2017, 143, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yadav, M.; Jamil, M.; Rizwan, M. Enabling Technologies for Smart Energy Management in a Residential Sector: A Review. In Proceedings of the Smart Cities—Opportunities and Challenges, Singapore, 21 April 2020; pp. 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kloppenburg, S.; Boekelo, M. Digital platforms and the future of energy provisioning: Promises and perils for the next phase of the energy transition. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 49, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fell, M.J.; Shipworth, D.; Huebner, G.M.; Elwell, C.A. Public acceptability of domestic demand-side response in Great Britain: The role of automation and direct load control. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 9, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khan, A.R.; Mahmood, A.; Safdar, A.; Khan, Z.A.; Khan, N.A. Load forecasting, dynamic pricing and DSM in smart grid: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 1311–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellabban, O.; Abu-Rub, H. Smart grid customers’ acceptance and engagement: An overview. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 65, 1285–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosbie, T.; Broderick, J.; Short, M.; Charlesworth, R.; Dawood, M. Demand Response Technology Readiness Levels for Energy Management in Blocks of Buildings. Buildings 2018, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faruqui, A.; Sergici, S. Household response to dynamic pricing of electricity: A survey of 15 experiments. J. Regul. Econ. 2010, 38, 193–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, F.; Basso, L.G.; de Santoli, L. Energy Use in Residential Buildings: Impact of Building Automation Control Systems on Energy Performance and Flexibility. Energies 2019, 12, 2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Batalla-Bejerano, J.; Trujillo-Baute, E.; Villa-Arrieta, M. Smart meters and consumer behaviour: Insights from the empirical literature. Energy Policy 2020, 144, 111610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brent, D.A.; Friesen, L.; Gangadharan, L.; Leibbrandt, A. Behavioral Insights from Field Experiments in Environmental Economics. Int. Rev. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2017, 10, 95–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyamfi, S.; Krumdieck, S. Price, environment and security: Exploring multi-modal motivation in voluntary residential peak demand response. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 2993–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gyamfi, S.; Krumdieck, S.; Urmee, T. Residential peak electricity demand response—Highlights of some behavioural issues. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 25, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, N.L.; Jeanneret, T.D.; Rai, A. Cost-reflective electricity pricing: Consumer preferences and perceptions. Energy Policy 2016, 95, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mert, W.; Watts, M.; Tritthart, W. Smart domestic appliances in sustainable energy systems-consumer acceptance and restrictions. In Proceedings of the ECEEE Summer Study: Act! Innovate! Deliver! Reducing Energy Demand Sustainably, Nice, France, 1–6 June 2009; pp. 1751–1761. [Google Scholar]

- Paetz, A.-G.; Dütschke, E.; Fichtner, W. Smart Homes as a Means to Sustainable Energy Consumption: A Study of Consumer Perceptions. J. Consum. Policy 2012, 35, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruqui, A.; George, S. Quantifying Customer Response to Dynamic Pricing. Electr. J. 2005, 18, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parag, Y.; Butbul, G. Flexiwatts and seamless technology: Public perceptions of demand flexibility through smart home technology. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 39, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Van Passel, S.; Laes, E. Assessing the success of electricity demand response programs: A meta-analysis. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 40, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaim, T.; Neenan, B.; Robinson, J. Pilot Paralysis: Why Dynamic Pricing Remains Over-Hyped and Underachieved. Electr. J. 2013, 26, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, P.; Leach, M.; Torriti, J. A review of the costs and benefits of demand response for electricity in the UK. Energy Policy 2013, 52, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shipman, R.; Gillott, M.; Naghiyev, E. SWITCH: Case Studies in the Demand Side Management of Washing Appliances. Energy Procedia 2013, 42, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ofgem. Energy Demand Research Project: Final Analysis; AECOM Building Engineering for Ofgem: Hetfordshire, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Western Power Distribution. SoLa Bristol SDRC 9.8 Final Report; Western Power Distribution: Bristol, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, J. Developing the Smarter Grid: The Role of Domestic and Small and Medium Enterprise Customers; Report from the Customer Led Network Revolution; Nothern Power Grid: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael, R.; Schofield, J.; Woolf, M.; Bilton, M.; Ozaki, R.; Strbac, G. Residential Consumer Attitudes to Time-Varying Pricing; Imperial College London: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Strengers, Y. Comfort expectations: The impact of demand-management strategies in Australia. In Comfort in a Lower Carbon Society; Shove, E., Chappells, H., Lutzenhiser, L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Parag, Y. Which factors influence large households’ decision to join a time-of-use program? The interplay between demand flexibility, personal benefits and national benefits. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 139, 110594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, A.; Leygue, C.; Bedwell, B.; O’Malley, C. Engaging with energy reduction: Does a climate change frame have the potential for achieving broader sustainable behaviour? J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Darby, S. The Effectiveness of Feedback on Energy Consumption: A Review for Defra of the Literature on Metering, Billing and Direct Displays; Working Paper; Oxford Environmental Change Institute: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Petkov, P.; Köbler, F.; Foth, M.; Krcmar, H. Motivating Domestic Energy Conservation through Comparative, Community-Based Feedback in Mobile and Social Media. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Communities and Technologies, Brisbane, Australia, 29 June–2 July 2011; Volume 11, pp. 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ehrhardt-Martinez, K.; Donnelly, K.; Laitner, J. Advanced Metering Initiatives and Residential Feedback Programs: A Meta-Review for Household Electricity-Saving Opportunities; American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mankoff, J.; Matthews, D.; Fussell, S.R.; Johnson, M. Leveraging Social Networks To Motivate Individuals to Reduce their Ecological Footprints. In Proceedings of the 2007 40th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS’07), Big Island, HI, USA, 3–6 January 2007; p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- Mankoff, J.; Fussell, S.R.; Dillahunt, T.; Glaves, R.; Grevet, C.; Johnson, M.; Matthews, D.; Matthews, H.S.; McGuire, R.; Thomson, R.; et al. StepGreen.org: Increasing Energy Saving Behaviors via Social Networks. In Proceedings of the Fourth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, Washington, DC, USA, 23–26 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, D.; Lawson, S.; Blythe, M.; Cairns, P. Wattsup? Motivating reductions in domestic energy consumption using social networks. In Proceedings of the 6th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Extending Boundaries, Reykjavik, Iceland, 16–20 October 2010; pp. 178–187. [Google Scholar]

- Burchell, K.; Rettie, R.; Roberts, T.C. Householder engagement with energy consumption feedback: The role of community action and communications. Energy Policy 2016, 88, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartusch, C.; Wallin, F.; Odlare, M.; Vassileva, I.; Wester, L. Introducing a demand-based electricity distribution tariff in the residential sector: Demand response and customer perception. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 5008–5025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugden, D.; Stedman, R. Unfulfilled promise: Social acceptance of the smart grid. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 034019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugden, D.; Stedman, R. A synthetic view of acceptance and engagement with smart meters in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 47, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, B.; Heptonstall, P.; Gross, R.; Sovacool, B.K. A systematic review of motivations, enablers and barriers for consumer engagement with residential demand response. Energy Policy 2020, 138, 111221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M.J.; Vocino, A.; Grau, S.L.; Garma, R.; Ferdous, A.S. The impact of general and carbon-related environmental knowledge on attitudes and behaviour of US consumers. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 238–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamm, B. The impacts of environmental knowledge and attitudes on vehicle ownership and use. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2009, 14, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Dane, G.; Finck, C.; Zeiler, W. Are building users prepared for energy flexible buildings?—A large-scale survey in the Netherlands. Appl. Energy 2017, 203, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilson, C.; Hargreaves, T.; Hauxwell-Baldwin, R. Smart homes and their users: A systematic analysis and key challenges. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2015, 19, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balta-Ozkan, N.; Davidson, R.; Bicket, M.; Whitmarsh, L. Social barriers to the adoption of smart homes. Energy Policy 2013, 63, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargraves, T.; Hauxwell-Baldwin, R.; Coleman, M.; Wilson, C.; Stankovic, L.; Stankovic, V.; Liao, J.; Murray, D.; Kane, T.; Hassan, T.; et al. Smart homes, control and energy management: How do smart home technologies influence control over energy use and domestic life? In Proceedings of the European Council for an Energy Efficient Economcy Conference 2015, Hyères, France, 1–6 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, R.; Paniamina, R. Smart Homes: What New Zealanders Think, Have, and Want. (Project Report); Centre for Sustainability, University of Otago: Dunedin, New Zealand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Abi Ghanem, D.; Larkin, A.; McLachlan, C. How the meanings of ‘home’ influence energy-consuming practices in domestic buildings. Energy Effic. 2020, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyborg, S.; Ropke, I. Constructing users in the smart grid-insights from the Danish eFlex project. Energy Effic. 2013, 6, 655–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powells, G.; Bulkeley, H.; Bell, S.; Judson, E. Peak electricity demand and the flexibility of everyday life. Geoforum 2014, 55, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abi Ghanem, D.; Crosbie, T. REACT Project Deliverable 4.1: Criteria and Framework for Participant Recruitment; Project Report; Centre for Sustainable Engineering, Teesside University: Middlesbrough, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gaur, A.S.; Fitiwi, D.Z.; Curtis, J. Heat pumps and our low-carbon future: A comprehensive review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 71, 101764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanthournout, K.; Dupont, B.; Foubert, W.; Stuckens, C.; Claessens, S. An automated residential demand response pilot experiment, based on day-ahead dynamic pricing. Appl. Energy 2015, 155, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torstensson, D.; Wallin, F. Exploring the Perception for Demand Response among Residential Consumers. Energy Procedia 2014, 61, 2797–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reiss, P.C.; White, M.W. Household Electricity Demand, Revisited. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2005, 72, 853–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, D.A.; Rosa, E.A.; Dillman, J.J. Lifestyle and home energy conservation in the United States: The poor accept lifestyle cutbacks while the wealthy invest in conservation. J. Econ. Psychol. 1983, 3, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, B.R. Dynamic Pricing? Not So Fast! A Residential Consumer Perspective. Electr. J. 2010, 23, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shove, E.; Chappells, H. Ordinary Consumption and Extraordinary Relationships: Utilities and Their Users; Gronow, J., Warde, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Shove, E. Converging Conventions of Comfort, Cleanliness and Convenience. J. Consum. Policy 2003, 26, 395–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warde, A. Consumption and theories of practice. J. Consum. Cult. 2005, 5, 131–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maréchal, K.; Holzemer, L. Getting a (sustainable) grip on energy consumption: The importance of household dynamics and ‘habitual practices’. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 10, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, T.H.; Friis, F.; Bettin, S.; Throndsen, W.; Ornetzeder, M.; Skjølsvold, T.M.; Ryghaug, M. The role of competences, engagement, and devices in configuring the impact of prices in energy demand response: Findings from three smart energy pilots with households. Energy Policy 2020, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis, F.; Haunstrup Christensen, T. The challenge of time shifting energy demand practices: Insights from Denmark. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 19, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, L.; Parag, Y. Motivations and barriers to integrating ‘prosuming’ services into the future decentralized electricity grid: Findings from Israel. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 21, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyborg, S. Pilot Users and Their Families: Inventing Flexible Pra ctices in the Smart Grid. Sci. Technol. Stud. 2015, 3, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, L.; Strengers, Y. Peak demand and the ‘family peak’ period in Australia: Understanding practice (in)flexibility in households with children. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 9, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Faiers, A.; Neame, C. Consumer attitudes towards domestic solar power systems. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 1797–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gärling, A.; Thøgersen, J. Marketing of electric vehicles. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2001, 10, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, T.; Brown, D. Grassroots retrofit: Community governance and residential energy transitions in the United Kingdom. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 78, 102102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breukers, S.; Crosbie, T.; van Summeren, L. Mind the gap when implementing technologies intended to reduce or shift energy consumption in blocks-of-buildings. Energy Environ. 2020, 31, 613–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abi Ghanem, D.; Mander, S. Designing consumer engagement with the smart grids of the future: Bringing active demand technology to everyday life. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2014, 26, 1163–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Socio-Demographic Variable | Survey Results | Wider Community (Regional Level) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inis Mór, Aran | Age | 65% or older: 30% | 65% or older: 25% |

| 55 to 64: 20% | 55 to 64: 15% | ||

| 45 to 54: 21% | 45 to 54: 18% | ||

| 35 to 44: 26% | 35 to 44: 20% | ||

| 25 to 34: 2% | 25 to 34: 13% | ||

| 18 to 24: 1% | 18 to 24: 8% | ||

| Gender | 64% Female; 36% Male | 51% Female; 49% Male | |

| Education | Primary: 7% | Primary: 7% | |

| Lower secondary: 13% | Lower secondary:15% | ||

| Leaving certificate: 23% | Leaving certificate: 24% | ||

| Post-leaving cert.: 16% | Post-leaving cert.: 14% | ||

| Third level: 41% | Third level: 40% | ||

| Carloforte, San Pietro | Age | 65% or older: 22% | 65% or older: 34% |

| 55 to 64: 19% | 55 to 64: 17% | ||

| 45 to 54: 30% | 45 to 54: 19% | ||

| 35 to 44: 16% | 35 to 44: 14% | ||

| 25 to 34: 13% | 25 to 34: 11% | ||

| 18 to 24: 0% | 18 to 24: 5% | ||

| Gender | 44% Female; 56% Male | 50.9% Female; 49.1% Male | |

| Education | Primary: 0% | Primary: 0% | |

| Middle school: 5% | Middle school: 28% | ||

| Diploma: 56% | Diploma: 29% | ||

| University level: 39% | University level: 43% | ||

| La Graciosa | Age | 65% or older: 14% | 65% or older: 21% |

| 55 to 64: 19% | 55 to 64: 11% | ||

| 45 to 54: 24% | 45 to 54: 24% | ||

| 35 to 44: 24% | 35 to 44: 20% | ||

| 25 to 34: 5% | 25 to 34: 15% | ||

| 18 to 24: 10% | 18 to 24: 9% | ||

| Wider community (National level) | |||

| Gender | Female: 52%; Male: 48% | Female: 50%; Male: 50% | |

| Education | Secondary: 5% | Secondary: 28% | |

| Diploma/vocational: 24% | Diploma: 27% | ||

| University level: 58% | University level: 45% | ||

| Heating | Cooling | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| La Graciosa | With Heating | 5% | With Cooling | 20% |

| Central | -- | Central | 50% | |

| Individual | 100% | Individual | 25% | |

| Both types | -- | Both types | 25% | |

| Other | -- | Other | -- | |

| Carloforte | With Heating | 81% | With Cooling | 67% |

| Central | 11% | Central | 85% | |

| Individual | 74% | Individual | 9% | |

| Both types | 10% | Both types | 2% | |

| Other | 5% | Other | 4% | |

| Inis Mór | With Heating | 100% | With Cooling | 5% |

| Central | 78% | Central | 75% | |

| Individual | 4% | Individual | 25% | |

| Both types | 6% | Both types | -- | |

| Other | 12% | Other | -- |

| Dimension for Adoption | Dimension of Adoption for the REACT Solution |

|---|---|

| Relative advantage | The advantages of DR are well known; however, knowledge of the principles and technologies of SG is low overall. |

| Compatibility | Previous research indicates that the flexibility that SG requires might not be easy to implement. The reluctance of respondents for adopting SG technologies suggests that perceived compatibility is low. |

| Complexity | The low levels of understanding of SG concepts and technologies is likely to be a result of the complexity of the concept and its application. |

| Trialability | The possibility to trial the REACT solution is an advantage here, particularly given the high costs if the REACT solution was to be available in an open market. |

| Observability | Financial benefits to households can be observed via lower electricity bills. The wider outcomes of SG technologies are not directly visible as these pertain to efficiencies to the grid, lower CO2 emissions and lower costs for the islands. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abi Ghanem, D.; Crosbie, T. The Transition to Clean Energy: Are People Living in Island Communities Ready for Smart Grids and Demand Response? Energies 2021, 14, 6218. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14196218

Abi Ghanem D, Crosbie T. The Transition to Clean Energy: Are People Living in Island Communities Ready for Smart Grids and Demand Response? Energies. 2021; 14(19):6218. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14196218

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbi Ghanem, Dana, and Tracey Crosbie. 2021. "The Transition to Clean Energy: Are People Living in Island Communities Ready for Smart Grids and Demand Response?" Energies 14, no. 19: 6218. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14196218

APA StyleAbi Ghanem, D., & Crosbie, T. (2021). The Transition to Clean Energy: Are People Living in Island Communities Ready for Smart Grids and Demand Response? Energies, 14(19), 6218. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14196218