The Learning Activation Approach—Understanding Indonesia’s Energy Transition by Teaching It

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Methodology and Research Problem—Understanding through Teaching

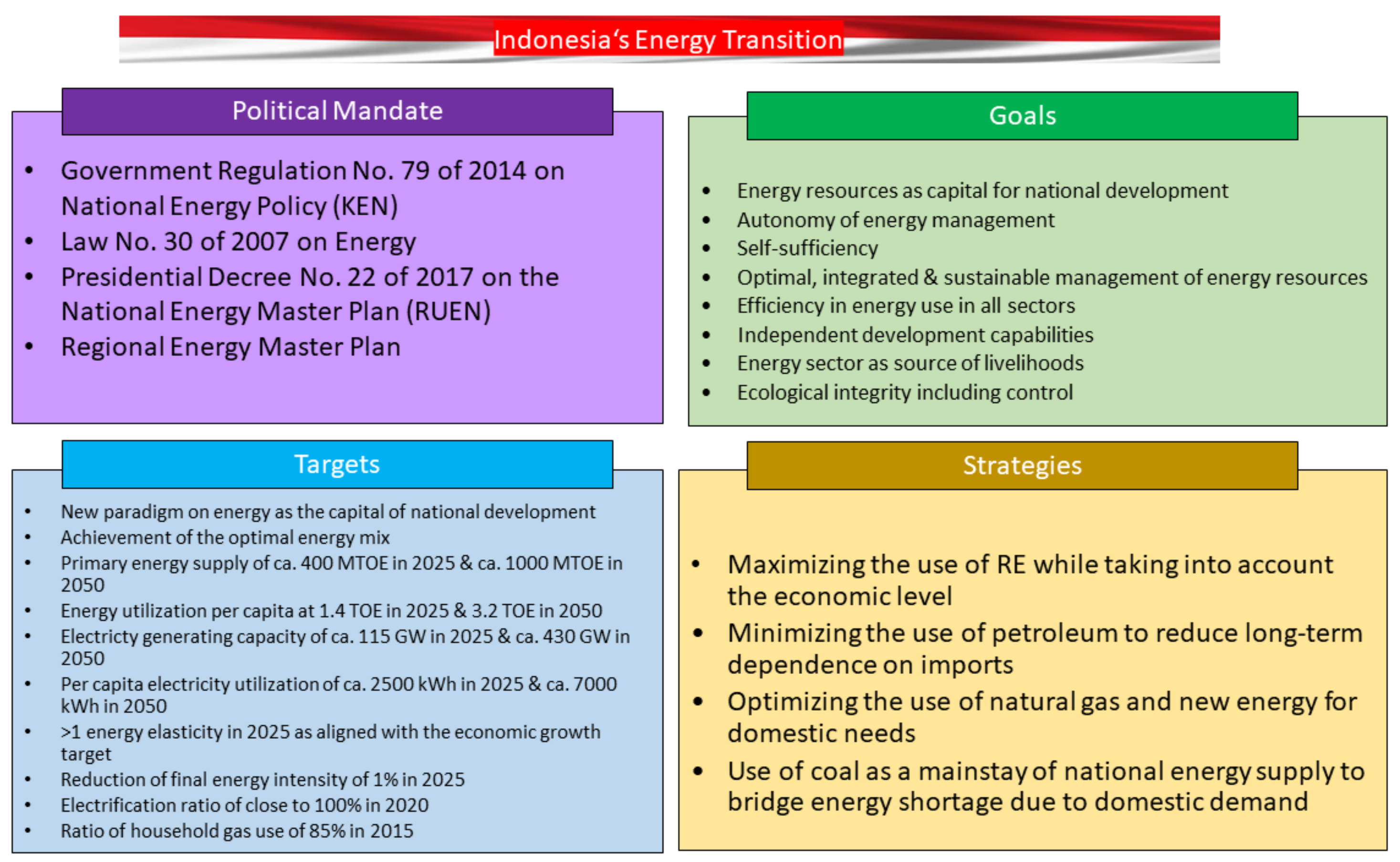

2. Teaching Guide—Understanding through Teaching of the Sustainable Energy Transition in Indonesia

2.1. Guidelines for Using the Case Study

2.1.1. Teaching Objectives and Target Audience—Building Future Change Makers

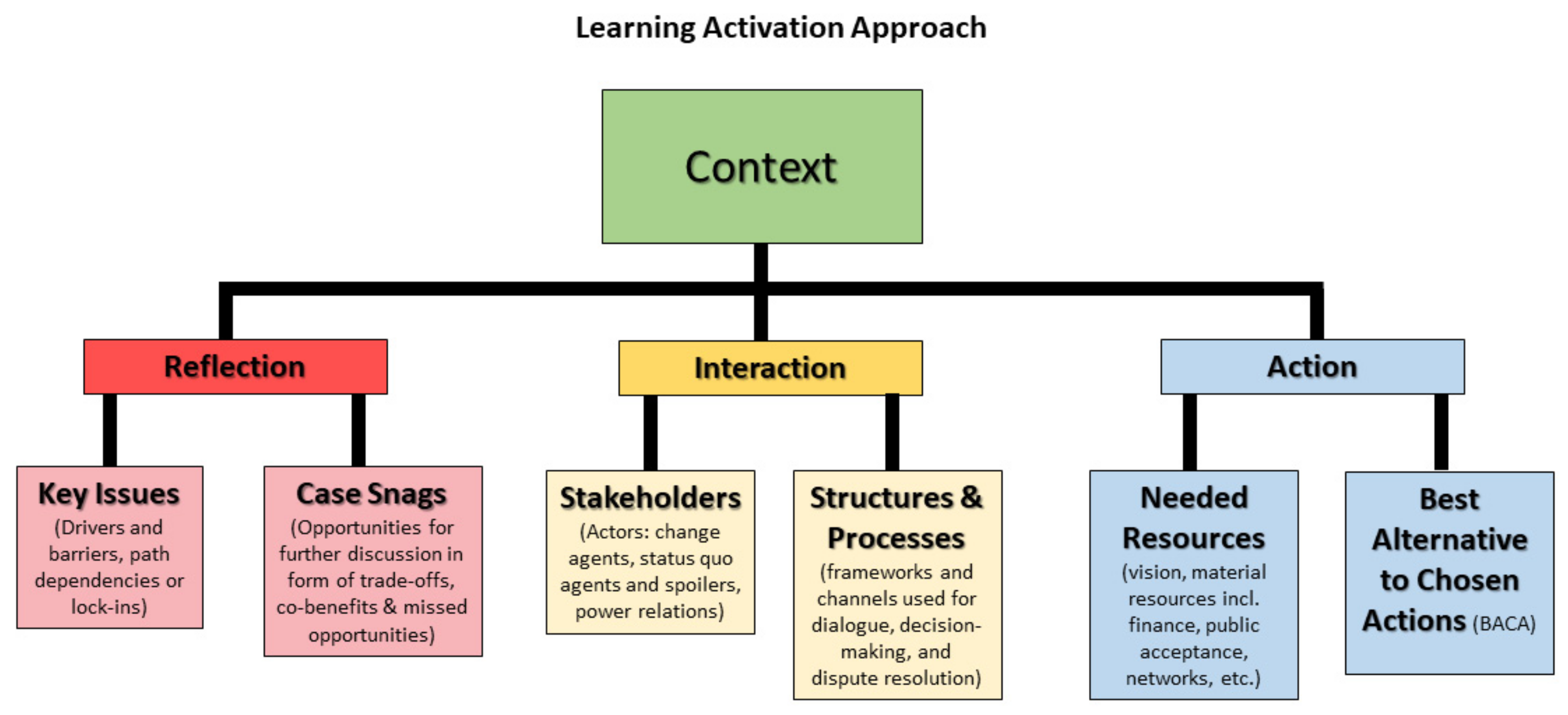

2.1.2. Teaching Approach and Strategy—Linking Reflection with Actions

2.2. Case Analysis—Learning from Indonesia’s Energy Transition

2.2.1. Geophysical and Ecological Context

- -

- -

- The limitations or challenges to Indonesia’s energy system resulting from the country being an archipelago with more than 17,000 islands that spans a distance of about 5000 km—equivalent to one-eighth of the Earth’s circumference [25].

Coal Energy as an Indispensable Part of Indonesia’s Energy Mix

The Energy–Human Development Nexus in an Archipelagic State—The Decentralisation of Indonesia’s Energy System

- -

- What international assistance is available to reduce emissions from Indonesia’s energy sector?

- -

- Does coal energy enjoy public support?

- -

- Is an increasing dependence on coal preventing the deployment of renewable energy in Indonesia?

- -

- Can technological innovation, for example in CCS, resolve the negative effects of coal energy on Indonesia’s climate change mitigation?

- -

- How can Indonesia decouple its GHG emissions from its energy demand?

- -

- Are the negative effects or trade-offs of coal energy (e.g., health, air pollution) shouldered by those earning from it?

- -

- Should domestic tax be introduced to help build up the needed infrastructures for renewable energy?

- -

- Is there political will and capability within the Indonesian government to relinquish coal energy?

- -

- How can the knowledge and understanding of policymakers at the national and local levels be increased to empower them to develop a policy and regulatory framework that supports renewable energy development and sustainability?

- -

- Is climate protection a viable argument to risk the reliability and affordability of energy in Indonesia? If not, can Indonesia realistically achieve its NDC with coal being as a mainstay energy?

- -

- Which additional efforts can be done to offset emissions from coal energy? Will Indonesia prefer emission trading schemes rather than actually reducing emissions?

- -

- Can improvements in energy efficiency be enough if emission trading schemes become too expensive?

2.2.2. The Economic Development Context

The High Monetary Costs of Indonesia’s Energy Transition

- -

- How will the current economic growth (in light of the COVID-19 pandemic) affect the implementation of the energy transition?

- -

- How will the energy transition in its current trajectory most likely affect Indonesia’s future economic growth?

- -

- The 2045 Indonesian Vision and Indonesia’s energy transition assume an economic growth driven by increasing domestic demand, including consumption and investment. Does economic growth need to be predominantly driven by consumption? There is a debate (e.g., about degrowth) that sustainable development and some principles of consumption are not compatible, because consumed resources are not only scarce but involve exploitation of natural resources [48].

- -

2.2.3. The Governance Context

Public Finance and the Resource Curse

The Role of State-Owned Enterprises (SEO) throughout the Entire Energy Value Chain in Indonesia

- -

- Should taxpayers shoulder the debt of Indonesia’s state-owned electricity company, PLN with its current short- and long-term debt of an estimated IDR 694.79 trillion?

- -

- Are state subsidies to energy companies reinforcing incompetent management?

- -

- Is the liberalisation or privatisation of the PLN the effective way to enhance its competitiveness? Should the energy sector remain under state control?

- -

- What was my connection to the energy issue before and did I discover new connections through the Indonesian case study?

- -

- Have I learned something new through the Indonesian case study that changed my view or position on one issue?

- -

- Did the Indonesian case study lead me to understand better the challenges confronting my home country?

- -

- Did I discover something from the Indonesian case study that can be applied to my home country?

- -

- Are there other areas of interest in each context that are also important and that should be further discussed?

- -

- Have I come up with a BACA that I never thought of before and of which I am now a “fan”?

- -

- How I learned something important by listening to the views or perspectives of my classmates?

3. Conclusions—Understanding through Teaching

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Indicators | Indonesia |

|---|---|

| Population [70] | 270.2 million (2019) |

| Size [73] | 1,916,906.77 km2 |

| Gross National Income (GNI), atlas method (current USD) | USD 4050 (2019) |

| GNI per capita [73] | IDR 59,054,440 (2019) |

| Gross Domestic Product (GDP) | USD 1.2 trillion (2019) |

| Unemployment rate [73] | 5.6% (2019) |

| Total primary energy production (2019) [70] | 411.6 MTOE (2018) (64% of which exported) |

| Total final energy consumption (without biomass) [70] | 114 MTOE (2018) |

| Energy intensity per capita [71] | 29.82 (MMBtu/person) (2018) |

| Primary energy supply [70,73] | 1,559,295 thousand BOE (2019) |

| NRE (share in primary energy supply mix) [73] | 9.18% (2019) |

| Oil (share in primary energy supply mix) [73] | 35.03% (2019) |

| Coal (share in primary energy supply mix) [73] | 37.28% (2019) |

| Gas (share in primary energy supply mix) [73] | 18.51% (2019) |

| Total renewables installed capacity (both on-grid and off-grid) | 10.17 GW [37] Hydropower: 5.4 GW Geothermal: 2.13 GW Bioenergy: 1.9 GW Mini/micro hydro: 464.7 MW Wind: 148.5 MW Solar PV: 152.4 MW Waste power plant: 15.7 MW |

| Final energy consumption [73] | 1007.26 million BOE (2019) |

| Primary energy supply per capita [73] | 5.92 BOE/capita (2019) |

| Primary energy consumption per capita [73] | 3.53 BOE/capita (2019) |

| Provision of power plants [70] | 66.8 GW (2018) |

| Electricity production in TWh [74] | 295 TWh (2019) |

| Electrification ratio [70] | 98.81% (2018) |

| Per-capita electricity utilisation [70] | 1077 KWh (2018) |

| Reduction of final energy intensity [70] | 1% annually (2019) |

| Ratio of household gas consumption [70] | 85% (2015) |

| Self-sufficiency level (% of TPES) [74] | 195% (2018, since 2018 increasing) |

| No. of people directly employed in the RE sector [72] | 519,200 (incl. 494,400 in liquid biofuels and 17,800 in hydropower) (2020) |

| Share of nuclear energy in % | None |

| CO2 emissions (metric tons per capita) [73] | 1.7 tonnes CO2 equi., per capita (2018) |

| GHG emission level (metric tons) [73] | 532 tonnes (2018)—an increase of 313% on 1990 levels |

| Share of global carbon emissions [9] | 1.68% (2018) |

| Production Activity | Saving Activity | Mitigation (Million Tonne CO2) | Estimated Cost (IDR Trillion) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electric NRE | 48.9 GW | 156.6 | 1688.0 | |

| Non-electric NRE | Biodiesel: 9.2 million KL Biogas: 19.4 million m3 | 13.8 | 84.0 | |

| Energy conservation | 117 TWh | 96.3 | 92.3 | |

| Clean technology | 102 GW | 31.8 | 1619.0 | |

| Oil and gas | LPG and kerosene conversion: 5.6 million ton Gas station: 143.75 MMSCFD Gas networks: 2.4 million SR | 10.0 | 16.6 | |

| Reclamation | 145,200 Ha | 5.5 | 4.0 |

| Context | Reflection | Interaction | Action | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key Areas | Case Snags | Stakeholders | Structures and Processes | Needed Resources | Best Alternative to Chosen Action | |

| Geophysical and ecological context | coal energy archipelagic statehood vulnerability to climate change | international assistance on mitigation CCS public acceptance of coal deployment of RE poverty-energy and education-energy nexus technological innovation | policy entrepreneurs role of non-state actors urban vs. rural peripheries | policy cycle clearing houses for islands coordination with other archipelago/island nations | infrastructures technological innovation in CCS policies to ensure reliability and affordability of energy | CCS energy subsidies emission trading carbon pricing energy efficiency improvement |

| Economic development context | post-pandemic economic growth bioenergy as driver of economic growth decoupling emissions from economic growth sustaining economic growth in an archipelagic state | new paradigms of economic growth post-COVID-19 recovery resource curse | public and private sectors exporting sectors (e.g., manufacturing) public sector non-state actors subnational actors (cities and regions) | national development planning | policy instruments that aim to ease trade relations | improving purchasing power of domestic households |

| Governance context | public finance SOEs decentralisation of the energy sector | liberalisation or privatisation of energy sector state subsidies to SOEs such as PLN | government agencies state-owned enterprises stakeholders to the energy sector | National Energy Council framework established by RENRUEN and RUED | public–private partnerships digitalisation diversification modernisation of infrastructure | community-based PPT roll-back of liberalisation decentralisation of the energy sector |

References

- Burhani, A.N. Al-Tawassut wa-l I’tidal: The NU and moderatism in Indonesian islam. Asian J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 40, 564–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, V.; Reichart, D. Indonesien auf der Globalen Bühne; Friedrich Ebert Stiftung: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Strydom, H. The Non-Aligned Movement and the Reform of International Relations. In Max Planck Yearbook of United Nations Law; Von Bogdandy, A., Wolfrum, R., Eds.; Koninklijke Brill N.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Penetrante, A. The Entanglement of Climate Change in North-South Relations: Stumbling Blocks and Opportunities for Negotiation. In Climate Change: Global Risks, Challenges and Decisions; Richardson, K., Steffen, W., Liverman, D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 356–359. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta, C. The Climate Change Negotiations. In Negotiating Climate Change: The Inside Story of the Rio Convention; Mintzer, I., Leonard, J.A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994; pp. 129–148. [Google Scholar]

- Climate Change Negotiations. A Guide to Resolving Disputes and Facilitating Multilateral Cooperation; Sjöstedt, G., Penetrante, A.M., Eds.; Earthscan from Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, C.; Widyanigsih, E. Indonesian Leadership in ASEAN: Mediation, Agency and Extra-Regional Diplomacy. In Indonesia’s Ascent; Roberts, C., Habir, A., Sebastian, L., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015; pp. 264–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. World Energy Balances 2020—Indonesia; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. E4 Country Profile: Energy Efficiency Indonesia; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Badan-Pusat-Statistik. Indikator Ekonomi Februari 2021; Badan-Pusat-Statistik: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S.; Iacobuta, G.; Hägele, R. Maximising goal coherence in sustainable and climate-resilient development? Polycentricity and coordination in governance. In The Palgrave Handbook of Development Cooperation for Achieving the 2030 Agenda; Chaturvedi, S., Janus, H., Klingebiel, S., Li, X., de Mello e Souza, A., Sidiropoulos, E., Wehrmann, D., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- BAPPENAS. Visi Indonesia 2045, Indonesia 2045: Berdaulat, Maju, Adil, Dan Makmur; Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Government-of-Indonesia. First Nationally Determined Contribution, Republic of Indonesia; Government of Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, A.W.L.; Lee, S.C.; Lim, S.W.H. The learning benefits of teaching: A retrieval practice hypothesis. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2018, 32, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ADB. Indonesian Energy Sector Assessment, Strategy, and Road Map. Update; Asian Development Bank: Manila, Philippines, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, A.M. Migration and “Unfinished” Modernization in the Philippines, Indonesia and Mexico. In Migración Internacional: Voces del Sur; González Becerril, J.G., Montoya Arce, B.J., Sandoval Forero, E.A., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México: Toluca, Mexico, 2017; pp. 265–282. [Google Scholar]

- Černoch, F.; Osička, J. ‘Emotional, erratic, anti-arithmetic and deeply consequential’: The Energiewende as seen from the Czech Republic. In Proceedings of the ECPR General Conference, Wroclaw, Poland, 4–7 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Polish Press Agency. Zelochowski: Poland May be Important for Kyoto Protocol. Polish Press Agency (PAP) News Wire. LexisNexis, 25 July 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Areeda, P.E. The Socratic method. Harv. Law Rev. 1996, 109, 911–922. [Google Scholar]

- Bazerman, M.; Shonk, K. The Decision Perspective to Negotiation. In The Handbook of Dispute Resolution; Moffitt, M., Bordone, R., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 52–65. [Google Scholar]

- Dupont, C.; Faure, G.O. The Negotiation Process. In International Negotiation. Analysis, Approaches, Issues; Kremenyuk, V., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 39–63. [Google Scholar]

- Raiffa, H. Negotiation Analysis: The Science and Art of Collaborative Decision Making; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fünfgeld, A. Coal vs Climate—Indonesia’s Energy Policy Contradicts its Climate Goals; German Institute for Global and Area Studies: Hamburg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tampubolon, A.P.; Arinaldo, D.; Adiatma, J.C. Coal Dynamics and Energy Transition in Indonesia; Institute for Essentual Services Reform: Jakarta, Indonesia; Global Environment Institute of China: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chatib Basri, M.; Rahardja, S. Indonesia. Navigating Beyond Recovery: Growth Strategy for an Archipelagic Country; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- DEN. Indonesia Energy Outlook 2019; Indonesia National Energy Council: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jong, H.N. Indonesia’s net-zero emissions goal not ambitious enough, activists say. Mongabay, 12 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, J. Bolsonaro’s Brazil is becoming a climate pariah. Climate News Network, 1 February 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bandt, A. Australia’s climate pariah status confirmed by UN Summit speaking list. The Greens, 11 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mawangi, G.T. Indonesia to chair G20 in 2022, exchanging presidency term with India. Antara News, 23 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, S.; Johnson, Z.; Zühr, R. Financing for the Future: Climate Finance and the Role of ODA. Donor Tracker Insights. Available online: https://donortracker.org/insights/financing-future-climate-finance-and-role-oda (accessed on 23 August 2021).

- BMWi. Coal; Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy: Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. Coal Information 2019; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell, T. Coal Is Dying and It’s Never Coming back: With or without Help from President Obama. Available online: https://www.motherjones.com/environment/2015/04/mitch-mcconnell-war-coal/ (accessed on 23 August 2021).

- MIT. The Future of Coal: Options for a Carbon-constrained World; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Edenhofer, O.; Steckel, J.C.; Jakob, M.; Bertram, C. Reports of coal’s terminal decline may be exaggerated. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 024019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IESR. Indonesia Clean Energ Outlook. Tracking Progress and Review of Clean Energy Development in Indonesia; Institute for Essential Services Reform: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- CPI; CIFOR. Powering the Indonesian Archipelago; Clean Power Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia; Center for International Forestry Research: Bogor, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- WB. Primary Education in Remote Indonesia: Survey Results from West Kalimantan and East Nusa Tenggara; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lauranti, M.; Djamhari, E.A. A Socially Equitable Energy Transition in Indonesia: Challenges and Opportunities; Friedrich Ebert Stiftung: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, P. The implications of an increasingly decentralized energy system. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4509–4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintrom, M.; Norman, P. Policy entrepreneurship and policy change. Policy Stud. J. 2009, 37, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayling, J.; Gunningham, N. Non-state governance and climate policy: The fossil fuel divestment movement. Clim. Policy 2017, 17, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippa, M.; Guizzardi, D.; Muntean, M.; Schaaf, E.; Solazzo, E.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Olivier, J.G.J.; Vignati, E. Fossil CO2 Emissions of All World Countries; Joint Research Centre (JRC), European Commission: Ispra, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tharakan, P. Summary of Indonesian Energy Sector Assessment; Asian Development Bank: Manila, Philippines, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Handrich, L.; Kempfert, C.; Mattes, A.; Pavel, F.; Traver, T. Turning Point: Decoupling Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Economic Growth; Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- MEMR. Statistics EBTKE 2016; Directorate General of New and Renewable Energy and Energy Conservation, Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Khmara, Y.; Kronenberg, J. Degrowth in the context of sustainability transitions: In search of a common ground. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 122072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auty, R. Sustaining Development in Mineral Economies: The Resource Curse Thesis; Routledge: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ploeg, F. Natural resources: Curse or blessing? J. Econ. Lit. 2011, 49, 366–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adger, W.N.; Brown, K.; Fairbrass, J.; Jordan, A.; Paavola, J.; Rosendo, S.; Seyfang, G. Governance for sustainability: Towards a ‘thick’ analysis of environmental decisionmaking. Environ. Plan. A 2003, 35, 1095–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, A. SDG-aligned Futures—Integrative Perspectives on the Governance of the Transformation to Sustainability. DIE Discuss. Pap. Ser. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitorus, S.; Rakhmadi, R.; Haesra, A.; Wijaya, M.E. Energizing Renewables in Indonesia: Optimizing Public Finance Levers to Drive Private Investment; Climate Policy Initiative: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Setyowati, A. Mitigating energy poverty: Mobilizing climate finance to manage the energy trilemma in Indonesia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wingvist, G.Ö.; Dahlberg, E. Indonesia Environmental and Climate Change Policy Brief; SIDA: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- WB. Indonesia at Risk Profile; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- BAPPENAS. Pembangunan Rendah Karbon; Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional (BAPPENAS): Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hilmawan, R.; Clark, J. An investigation of the resource curse in Indonesia. Resour. Policy 2019, 64, 101483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Von Haldenwang, C.; Ivynyna, M. Does the political resource curse affect public finance? The vulnerability of tax revenue in resource-dependent countries. J. Int. Dev. 2018, 30, 323–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Komarulzaman, A.; Alisjahbana, A. Testing the Natural Resource Curse Hypothesis in Indonesia: Evidence at the Regional Level. Working Papers in Economics and Development Studies (WoPEDS); Department of Economics, Padjadjaran University: Jawa Barat, Indonesia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tani, S. Indonesia to digitalize state-owned enterprises for competitiveness. Nikkei Asia, 2 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. Share of Government/SOE Ownership in Global Energy Investment by Sector, 2015 Compared to 2019; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Prag, A.; Röttgers, D.; Scherrer, I. State-owned Enterprises and the Low-carbon Transition; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Investing in Climate, Investing in Growth; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Asia Sentinel. Cleaning up Indonesia’s state-owned enterprises. Asia Sentinel, 1 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guild, J. Indonesia’s state-owned power company is hemorrhaging cash—And that’s OK. The Diplomat, 29 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Adburrahman, S. Impact of Covid-19 on Indonesia energy sector. In Proceedings of the ERIA Webinar, Jakarta, Indonesia, 10 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform—Indonesia; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- EPA. Community Based Public-private Partnerships (CBP3s) and Alternative Market-based Tools for Integrated Green Stormwater Infrastructure; United States Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- DEN. Outlook Energi Indonesia; Dewan Energi Nasional: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. World Energy Balances. Overview; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA. Renewable Energy Employment by Country. International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi, UAE. Available online: https://www.irena.org/Statistics/View-Data-by-Topic/Benefits/Renewable-Energy-Employment-by-Country (accessed on 23 August 2021).

- MEMR. Handbook of Energy & Economic Statistics of Indonesia; Indonesia Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. Statistics Report. World Energy Balances. Overview; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wakil-Menteri-ESDM. Koherensi Kebijakan Sektor ESDM DanLingkungan Hidup, Instrumen Dan Pendekatan Dalam Sasaran Ekonomi Dan Pengendalian Iklim; Kementarian Energi Dan Sumber Daya Mineral: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hernandez, A.M.; Prakoso, Y.T.B. The Learning Activation Approach—Understanding Indonesia’s Energy Transition by Teaching It. Energies 2021, 14, 5224. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14175224

Hernandez AM, Prakoso YTB. The Learning Activation Approach—Understanding Indonesia’s Energy Transition by Teaching It. Energies. 2021; 14(17):5224. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14175224

Chicago/Turabian StyleHernandez, Ariel Macaspac, and Yudhi Timor Bimo Prakoso. 2021. "The Learning Activation Approach—Understanding Indonesia’s Energy Transition by Teaching It" Energies 14, no. 17: 5224. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14175224

APA StyleHernandez, A. M., & Prakoso, Y. T. B. (2021). The Learning Activation Approach—Understanding Indonesia’s Energy Transition by Teaching It. Energies, 14(17), 5224. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14175224