1. Introduction

The coal gasification technology plays an important role in the global economy. It is used mainly to produce chemical substances; 24% of global ammonia output and 55% of methanol are now produced using the coal gasification technology.

Figure 1 presents a final products oriented structure of the application of gasification technology.

In 2018 there were 451 industrial gasification plants operating worldwide, equipped with 1074 reactors of total power of 206 GWth (chemical energy in the produced gas); 129 plants were under construction, equipped with 255 reactors of total power of 108 GWth, and at the stage of planning there were 135 plants equipped with 667 gasification reactors [

1]. A significant increase in the installed capacity occurred after 2010, resulting in 290% growth. Such a substantial increase was caused primarily by a huge demand for gasification technologies in Asia, where during 8 years (2010–2018) an approximately six-fold increase in the installed capacity was recorded (from 26.2 GWth to more than 150 GWth) [

1,

2].

There are a few types of reactor used to conduct the process. Entrained bed reactors are most frequently used in the case of coal gasification, featuring high process efficiency and productivity. Fluidized and fixed bed reactors are usually applied to gasify low-quality coals, biomass and wastes.

A wide application of the gasification intensifies the demand for reliable design tools and in depth understanding of thermochemical transformations proceeding in the reactor. One can find in the literature a relatively large number of described models. Reviews, classification, and application areas of solid fuels gasification models are presented in [

3,

4,

5,

6]. They refer to results of studies usually related to laboratory-scale test plants. Unfortunately, the models’ validation with the use of results obtained from industrial plants is missing. Because of that, published models—namely stoichiometric, equilibrium, kinetic or their hybrids—do not reflect all significant issues related to the gasification modelling. They also do not allow to use them reliably for other applications or reactor scales, primarily due to the accumulation of errors in underestimated reactions in equivalent pseudo-equilibrium constants or kinetic parameters.

Models described in the literature are usually based on a one-stage approach, i.e., consider only a classical set of gasification reactions [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. These models are used primarily for gasification carried out at temperatures much higher than 1000 °C, where the equilibrium conditions may be applied with a relatively good approximation. The existence of two types of reaction, homo- and heterogeneous, may be also considered in this modelling [

12]. Models, taking into consideration a two-stage fuel conversion, i.e., pyrolysis and gasification, are the second group [

13,

14,

15]. These models are used mainly for processes occurring at temperatures of 750–1000 °C, basically carried out in fluidized bed rectors, however this approach should be also important in the analysis of high temperature gasification.

In [

16] the two competing rates models were used to describe the devolatilization rate, basically distinguishing only volatiles and a char. The specific gaseous species composition was evaluated assuming arbitrary chosen parametric reactions. It is not clear whether the material balance at the pyrolysis step was closed. In [

17] the authors did in depth analysis of different pyrolysis models which can be used in gasification modelling. It was concluded that the models of Ranzi [

18] and Anca-Couce [

19] are most appropriate for that purpose. However, those models are based on an arbitrary chosen set of reactions considering biomass morphology, i.e., lignin, cellulose and hemicellulose, not a chemical elements composition. In this situation it is hard to apply the model for other fuels as well as perform a material and energy balance of the pyrolysis. The same problem can be encountered with the application of the Anca-Couce model. In an extensive review of coal gasification published in [

20], the authors discussed a number of published pyrolysis models; however, they are suitable either only for coal or there is a problem with closure of material and energy balances relevant for the process analysis of any gasification reactor.

However, irrespective of the reactor type or the temperature range of carried out reactions, the fuel is introduced at ambient conditions or close to it, and due to that in the first stage it must be heated to the reaction temperature. Taking into account that grains are heated in the fluidized bed at an average rate of 5000 °C/s, and in entrained bed reactors a few times faster, the grains achieve the reaction temperature in a fraction of a second. An intensive thermal decomposition (pyrolysis) of the organic matter dominates in this period and because of that oxygen has no access to the solid residue, i.e., char. Only after the release of volatile matter can the oxygen react with it in the gaseous phase or with the formed char in the heterogeneous phase. Taking this into account, it was assumed throughout that work that the entire gasification process is composed of a pyrolysis reaction stage which is followed by a gasification reaction stage. From this point of view, pyrolysis, which is the first stage of solid fuel conversion, becomes an important element of the process, first of all when deciding about gas phase composition and properties of char, and about heat demand, because it may consume the main portion of heat delivered for the reaction. This stage is non-isothermal, raising solid fuel temperature to the final one. The gasification reaction which follows is basically isothermal, and the pyrolysis products undergo decomposition due to interaction basically with oxygen or/and steam. Considering the above, it is important to distinguish both stages in the process of modelling and to analyze the share of energy needs for each of them. This will allow determining the effect of fuel type as well as process differences. At the pyrolysis stage, two key thermodynamic parameters are important from the point of view of energy balance, but also of the final products composition, i.e., the heat demand for pyrolysis, and enthalpy of pyrolysis reaction determined at standard conditions.

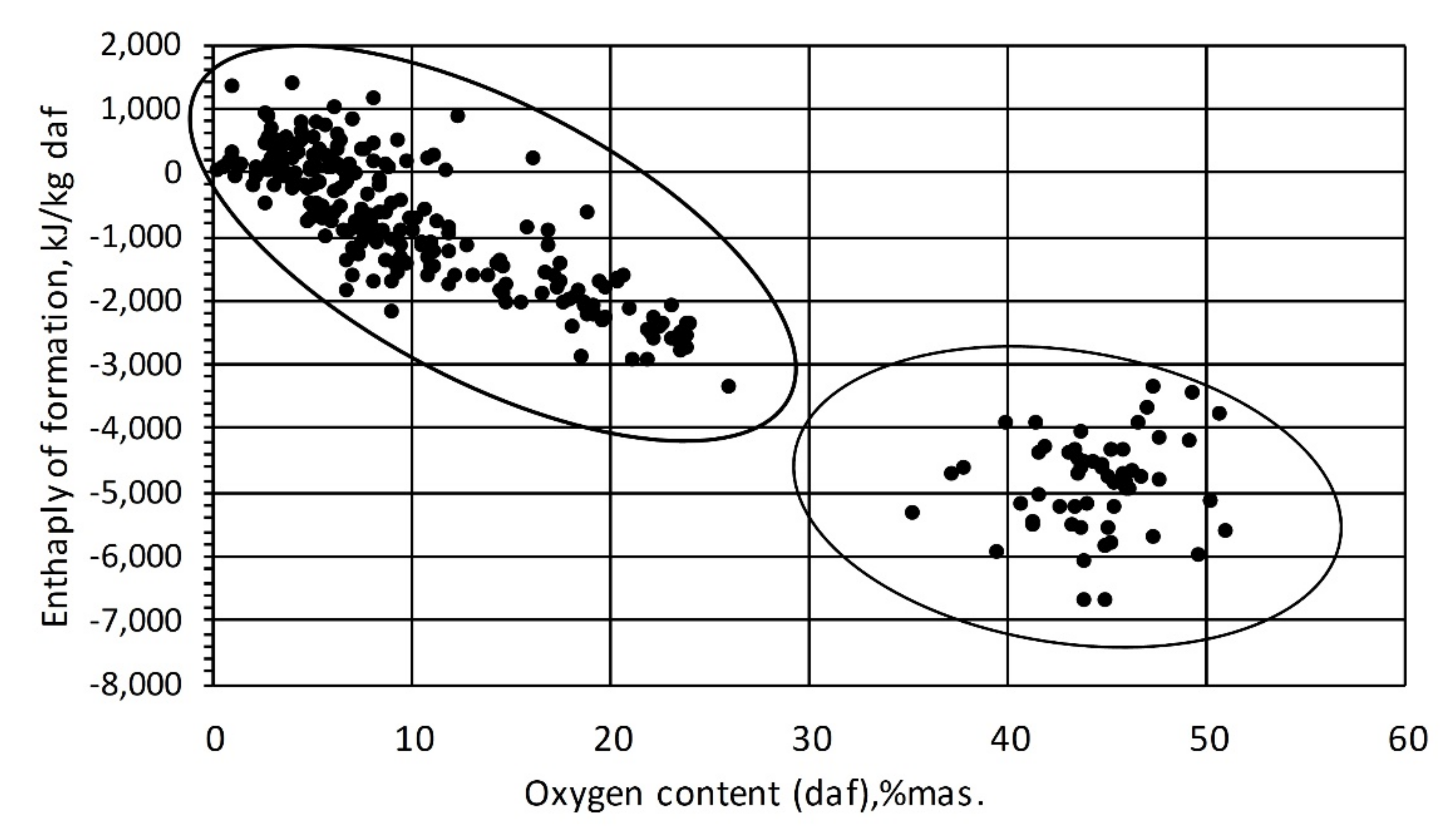

The modelling of fuels’ thermal conversion systems requires the knowledge of correct standard values of the enthalpy of formation for reactants and products. It allows real thermal effects of the reaction to be calculated and, as a result, the final process temperature affecting the potential equilibrium condition of chemical reactions existing in the process. In the case of fuels gasification this translates into the produced gas composition—the key parameter affecting the efficiency of the entire technological process.

Based on the knowledge of standard enthalpies of formation for process reactants and products, it is possible to determine a standard enthalpy of chemical reaction in accordance with a general relationship (1):

In reactions, in which only defined chemical substances take part, the determination of the enthalpy of reaction is relatively simple due to the availability of standard thermodynamic data of enthalpy of formation for pure substances [

21].

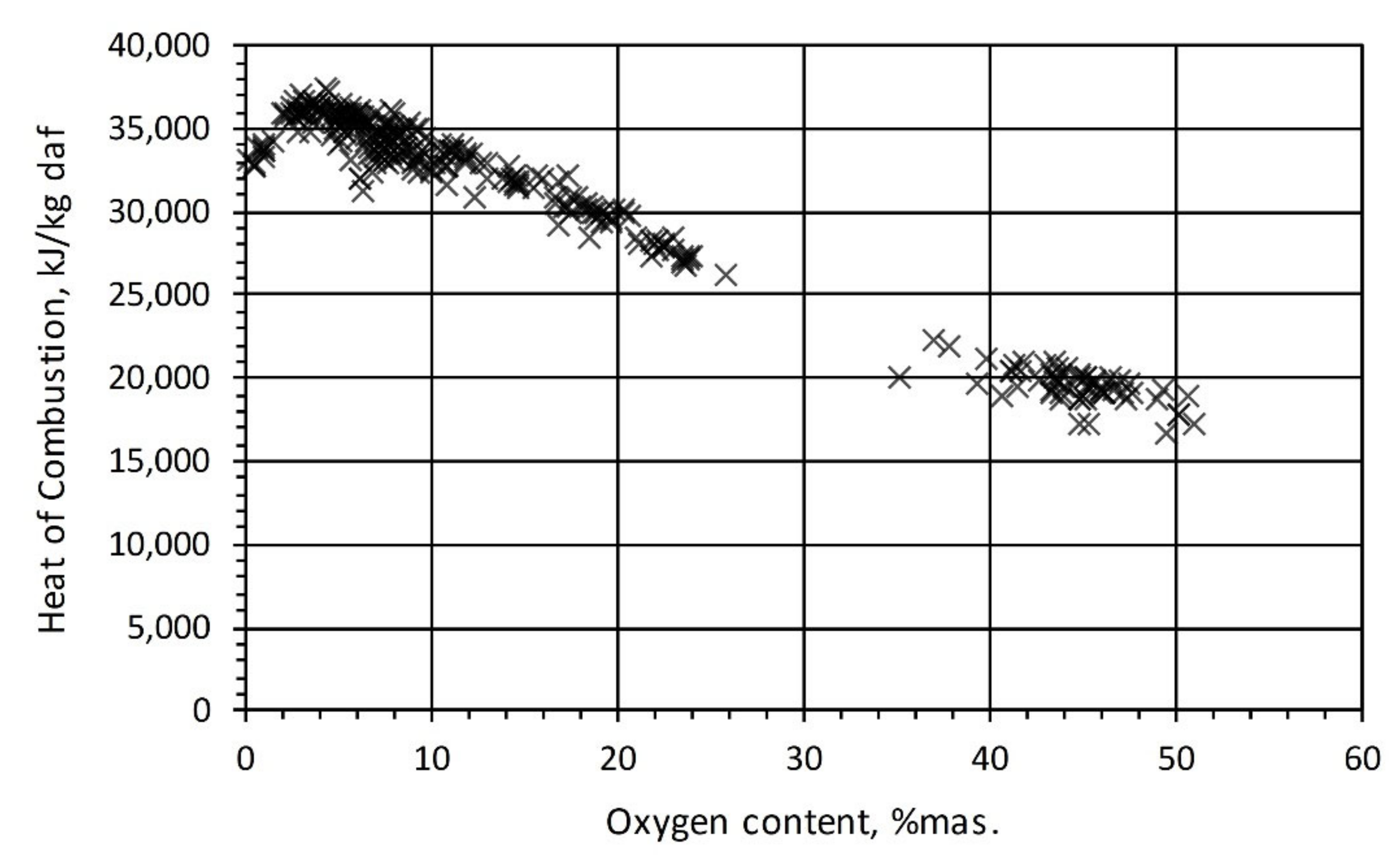

In the case of coal or biomass it becomes more complicated, because the heat of combustion determined calorimetrically is not equal to the computational value of the heat of reaction determined from relationship (1), assuming that the fuel is a mixture of elements existing in their standard states [

22,

23]. The difference between these values is defined as enthalpy of formation, which should be accounted for in energy balances performed on the process.

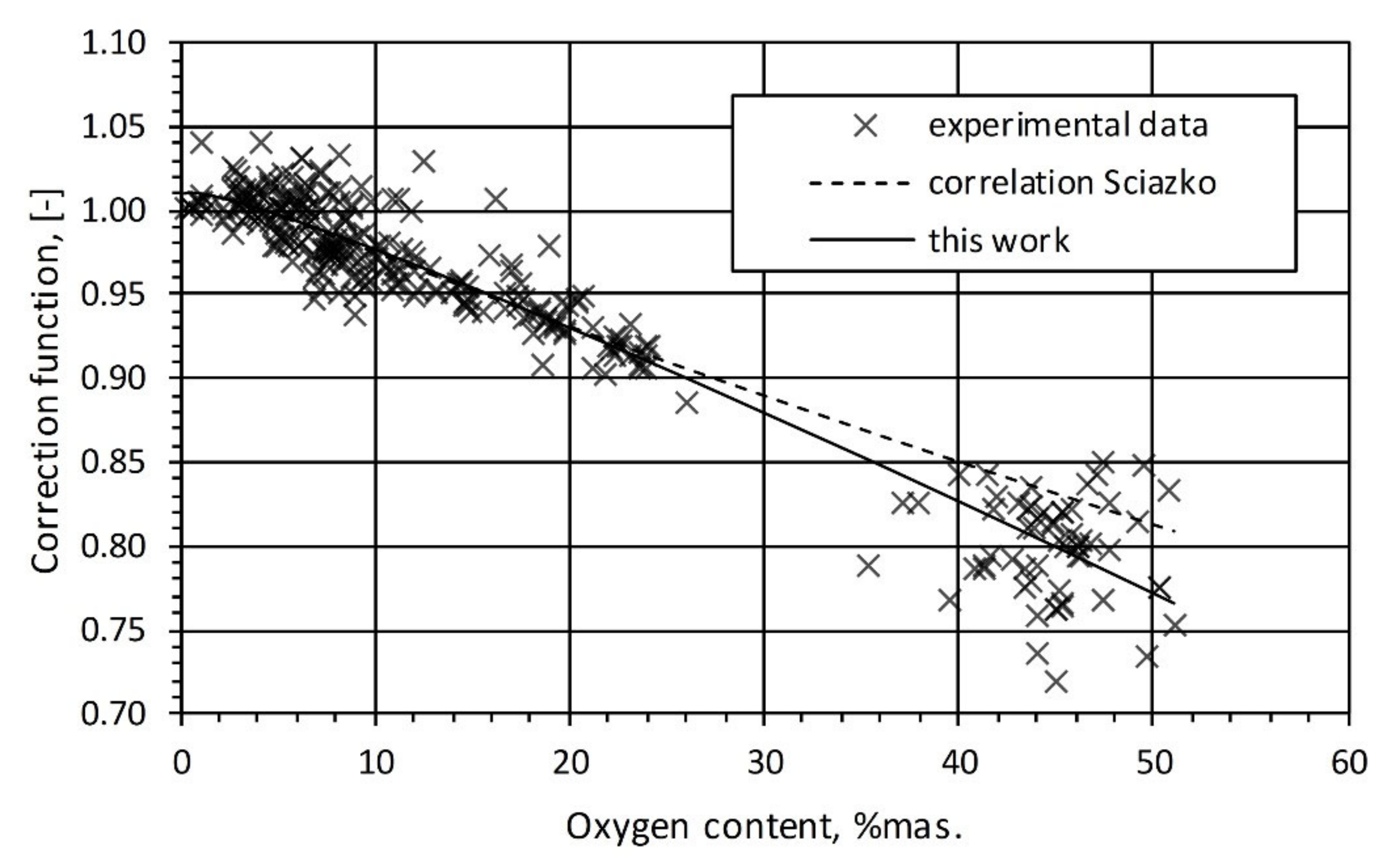

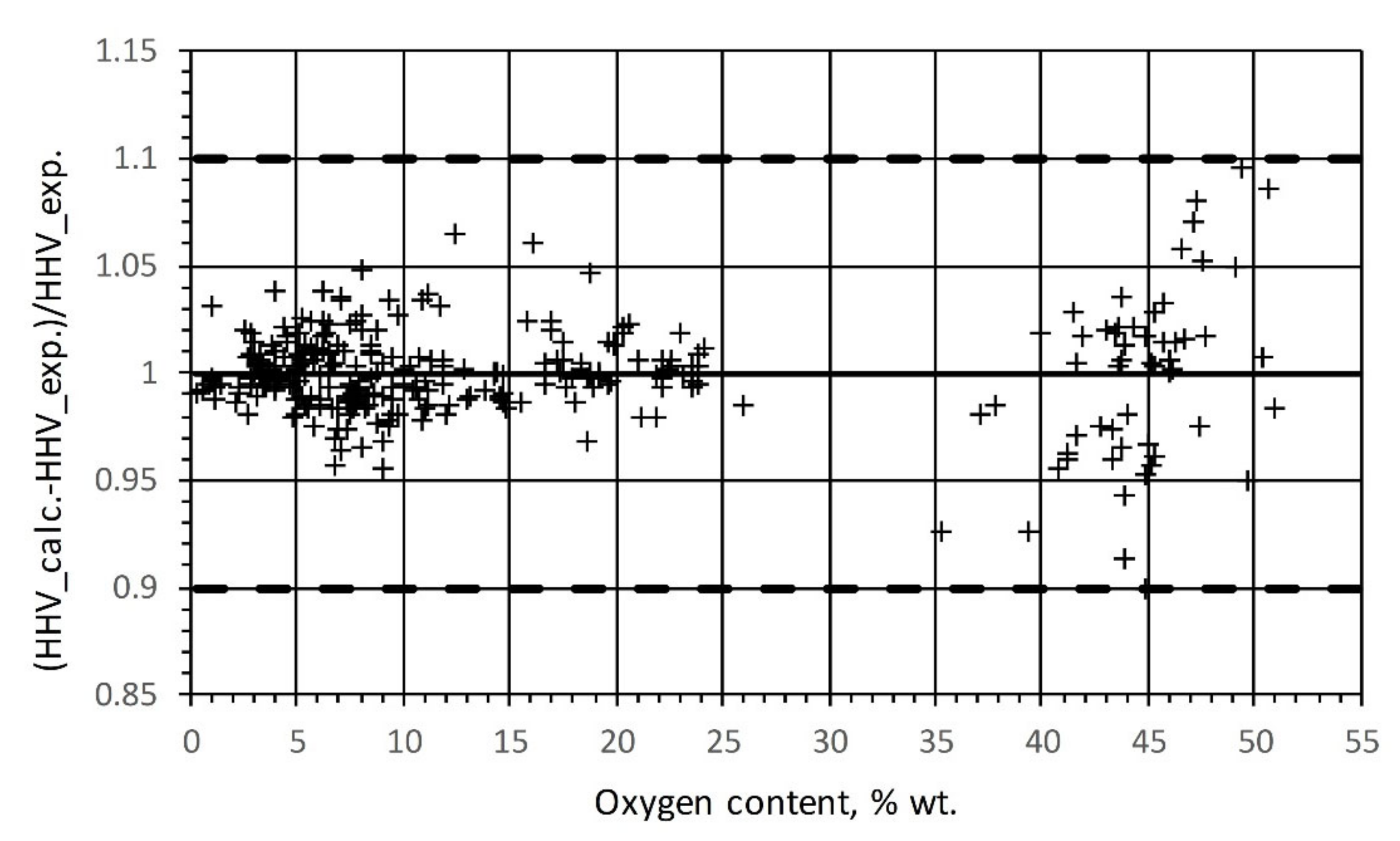

There is no clearly validated formula on enthalpy of formation which can be used for the entire range of fuels, i.e., from coal to biomass and wastes. The paper expands the computational formula for fuels enthalpy of formation, described for coal in [

23], on biomass and alternative fuels. The paper also discusses the impact of the enthalpy of formation for solid fuels on the results of the gasification process modelling in terms of energy balance. The obtained results have been compared against available literature data collected on real demonstration and industrial systems of coal or biomass gasification.

The gasification process model computations were performed using a ChemCAD computer code [

24]. Like other similar computational tools (Aspen, EES), in the process energy balancing accounts for the enthalpy of substance formation used in chemical thermodynamics, in the case of the fuels under consideration based on elemental composition. To unify the computations over the entire range of carbon content, the formula derived in this work was applied. In the case of pyrolysis modeling a MathCad [

25] computing environment was used for running in house developed simulation codes.

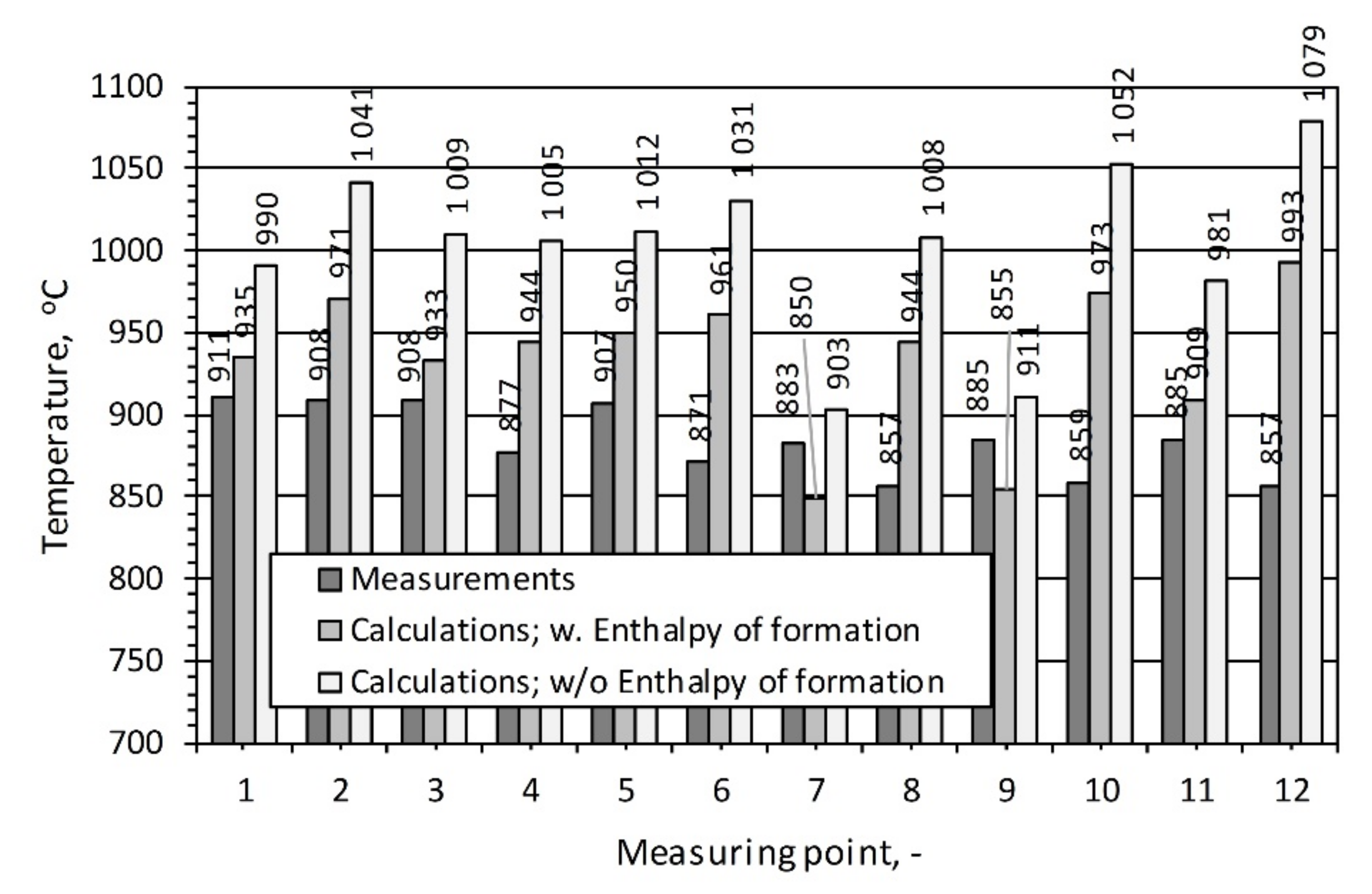

Based on the process computations carried out and balances verified by means of experimental data in fluidized bed and entrained bed reactors, processing both biomass and coal, the share and role of pyrolysis in the entire gasification process is discussed.

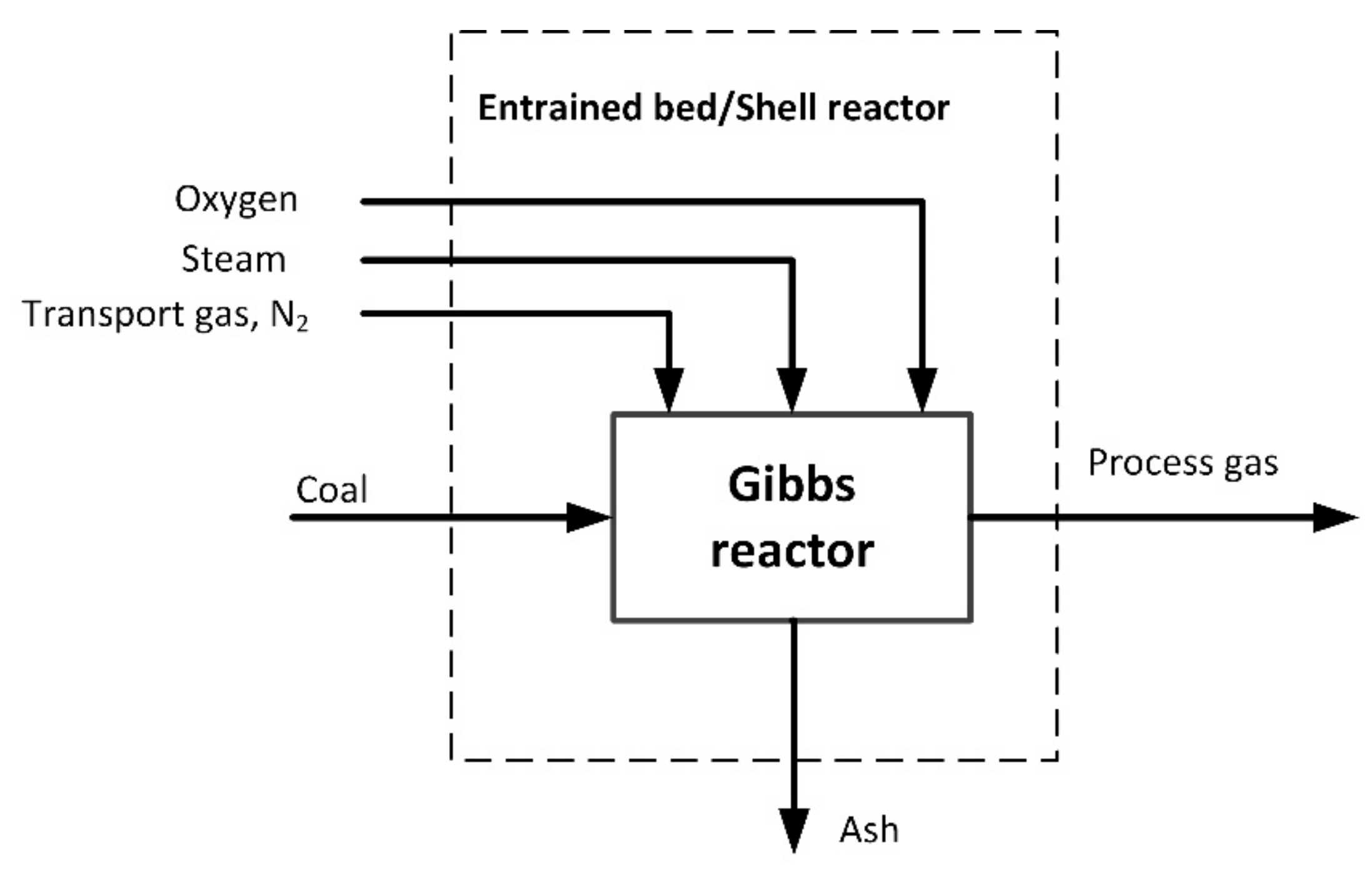

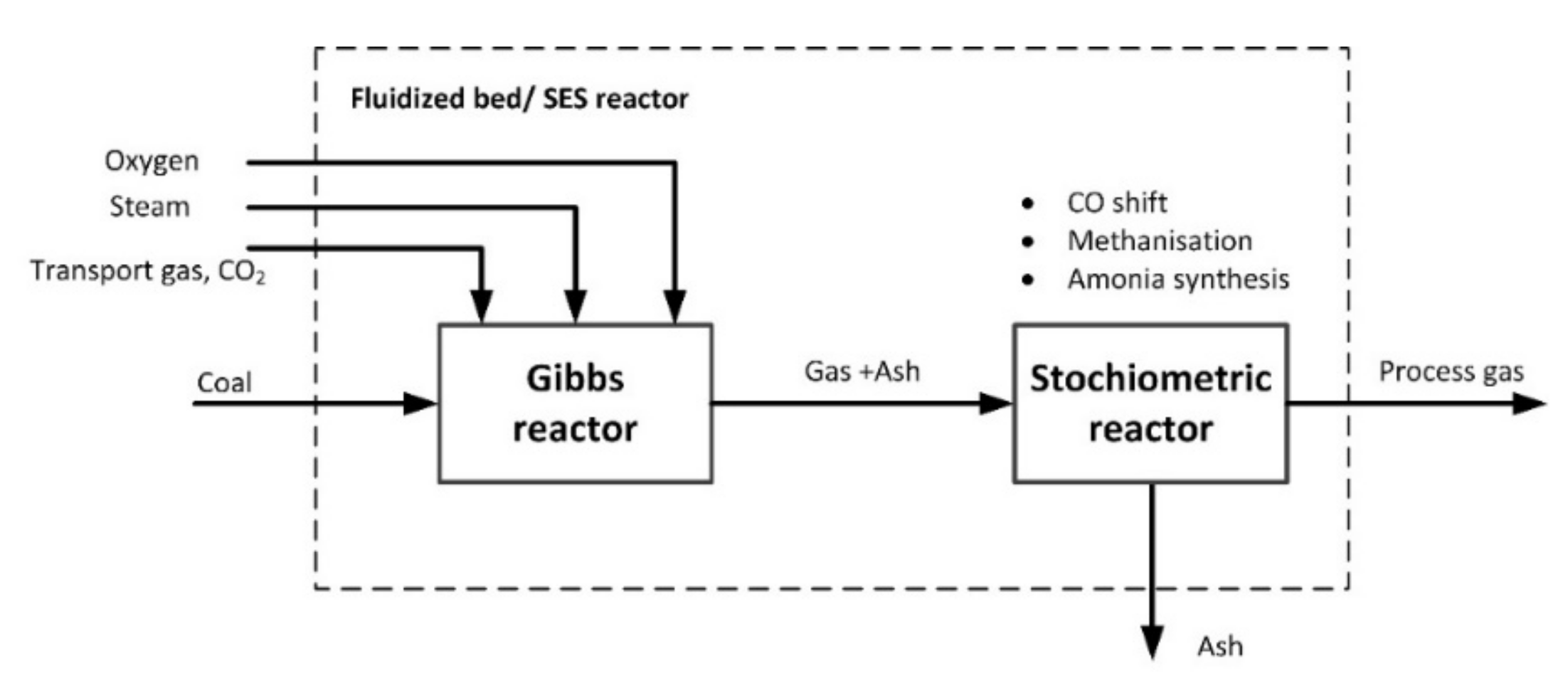

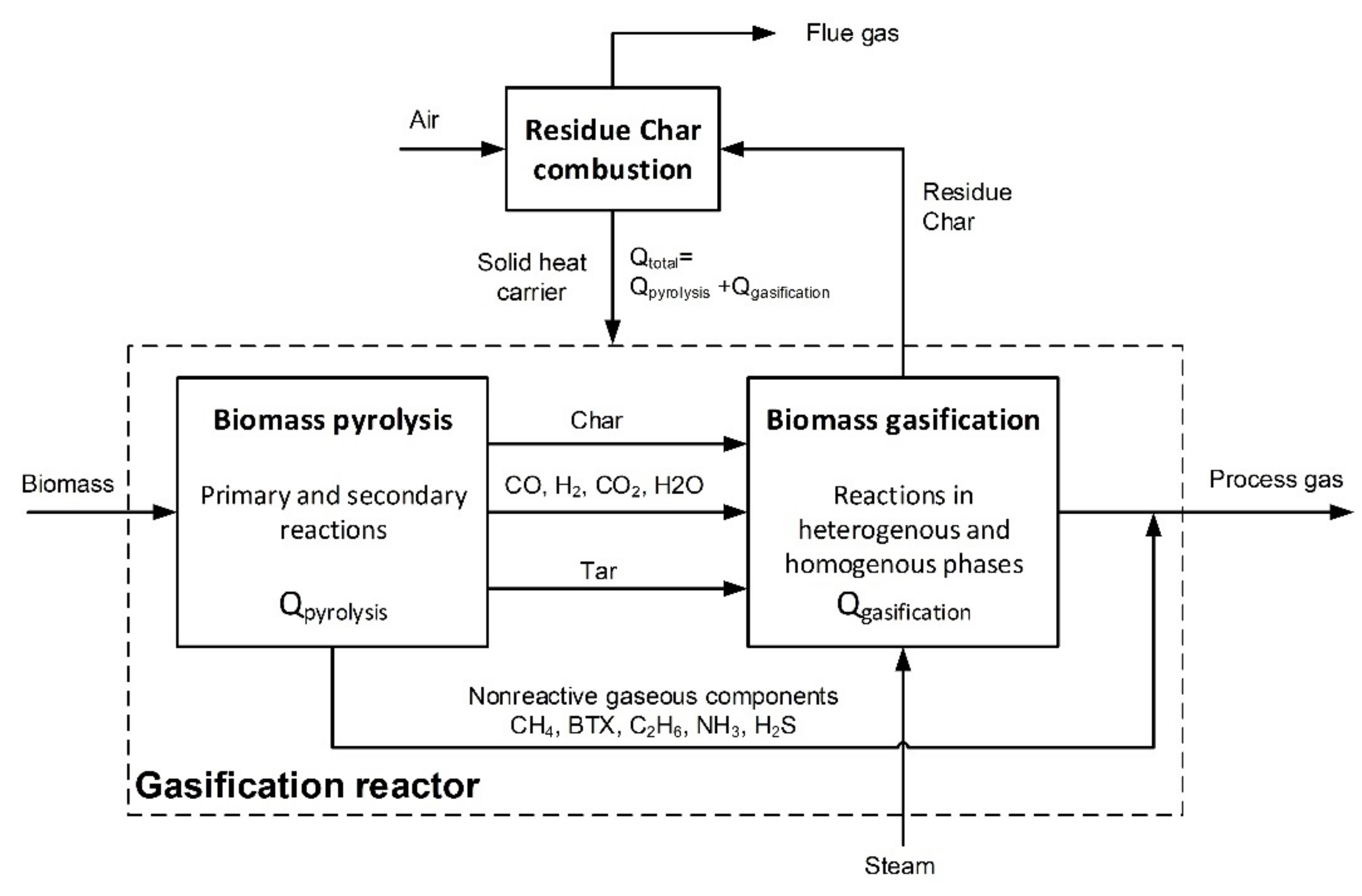

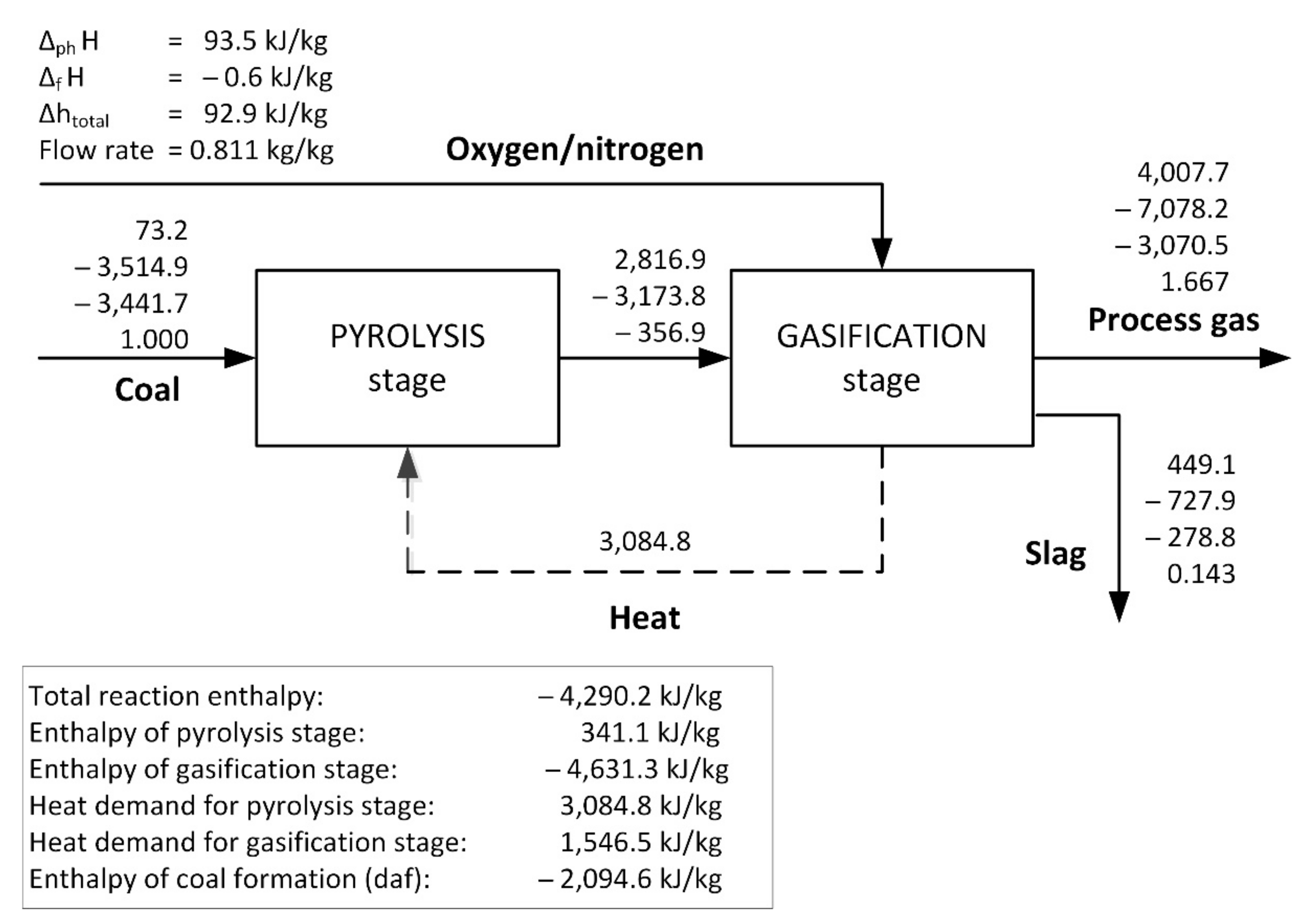

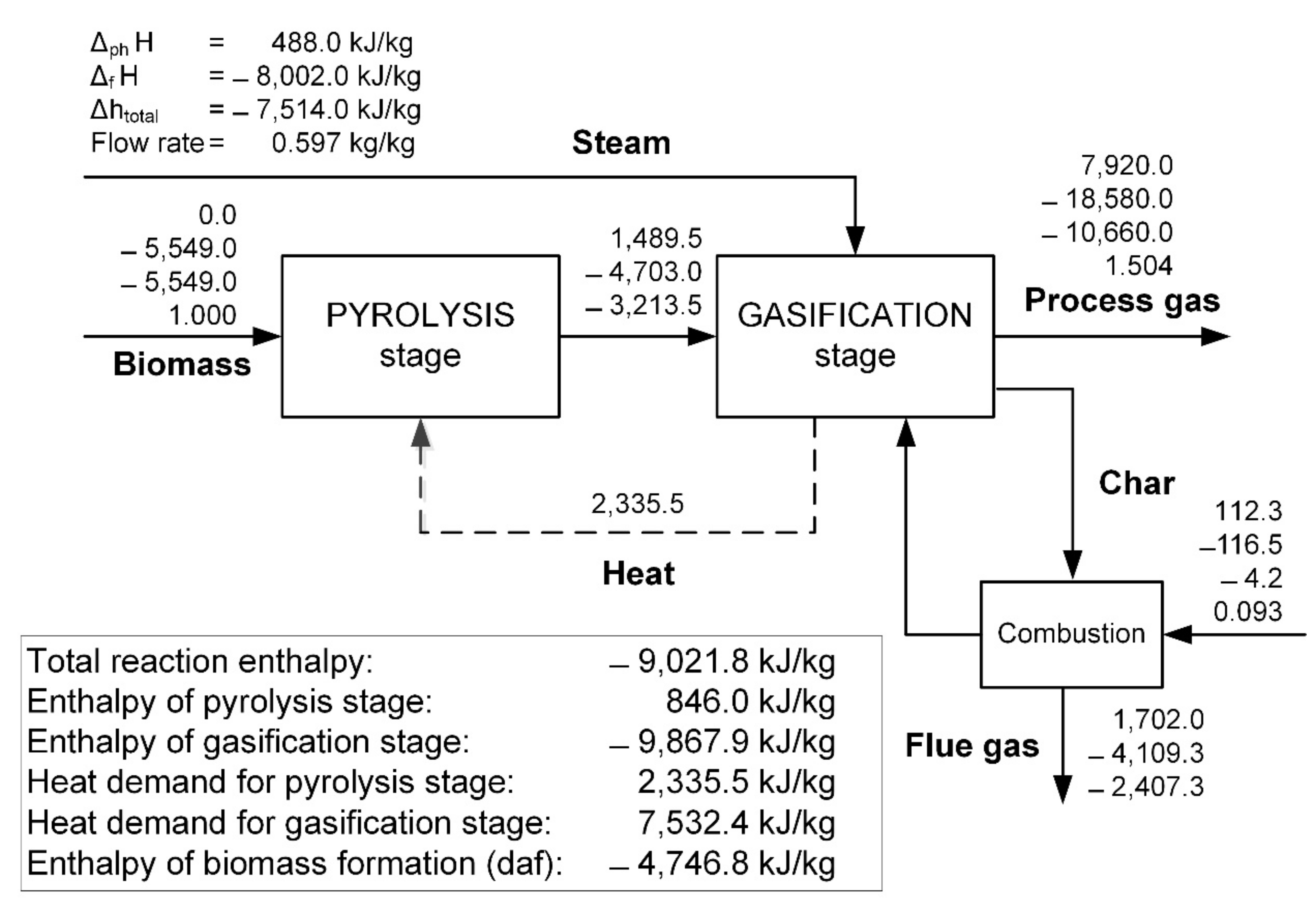

The process computations were made using the developed models of coal gasification in an entrained bed reactor with a dry feed (Shell technology, now The Air Products Gasification Process DSC (dry-feed syngas cooled) [

26] and a fluidized bed reactor (based on the SES (synthesis energy systems) technology) [

27]. In the case of biomass gasification, the developed model applies to the gasification system in a dual-bed type reactor, developed at the TU Wien (DFB, dual fluid bed) [

28]. This technology, under the name of FICFB (fast internal circulating fluid-bed), was applied for the biomass gasification system in Güssing (Austria). The processes listed above are developed and applied in industrial scale and the data from those large scale units were used for the analysis of process performance in terms of heat demand and enthalpy flow considering the two-stage reaction system.

4. Conclusions

Considering thermodynamic analysis of the gasification process it was assumed that it is composed of two successive stages, namely: pyrolysis reaction followed by a stage of gasification reaction. An intensive thermal decomposition (pyrolysis) of the organic matter dominates in the first period of fuel processing and because of that oxygen has no access to the solid residue, i.e., char. Only after the release of volatile matter can the oxygen react with it in the gaseous phase or with the char formed in the heterogeneous phase. This approach allows us to formulate the models of a selected gasification processes dominating in industrial applications. The data used for analysis were collected from industrial-scale operation units in case of Shell and SES gasification. In the case of biomass gasification, DFB demonstration-scale data were used.

Analysis of the energy balance, which is necessary for process modelling, leads to the conclusion that the enthalpy of fuel formation is essential for the correctness of the computed results. There was not a clearly validated formula on enthalpy of formation, which can be used for an entire range of fuels, i.e., from coal to biomass and wastes. This work delivers the computational formula for wide range of fuels enthalpy of formation, and discusses the impact of the enthalpy of formation on results of gasification process modelling in terms of energy balance. The obtained results have been compared against available literature data collected on real demonstration and industrial systems of coal or biomass gasification.

Different configurations of process analysis for thermodynamic modelling were developed and suitable ChemCAD based computing was performed to show the conditions for model validation. It was shown that in all three cases the enthalpy of formation play an important role, particularly related to the fuel rank.

Splitting the gasification process into two stages the following categories were evaluated in terms of energy balance:

Total reaction enthalpy;

Enthalpy of pyrolysis stage;

Enthalpy of gasification stage;

Heat demand for pyrolysis reaction;

Heat demand for gasification reactions.

In all cases the effect of enthalpy of formation was under consideration.

Total reaction enthalpy is very much dependent on the value of fuel formation enthalpy. It is clearly noticeable that the higher the enthalpy of the reaction the higher the formation enthalpy and this is not dependent on the final temperature of the process. Enthalpy of the pyrolysis stage is always positive as this is an endothermic reaction. However, the effect for biomass is more than twice greater than for coal.

The most interesting are the results of comparable energy analysis of the considered processes assuming the same moisture content in a fuel. In this case, the heat demand for pyrolysis and gasification separately were identified.

Considering the Shell process it was shown that the relation of heat demand for pyrolysis is almost twice greater than that of the heat necessary for gasification reaction. This difference is largely created by the value of formation enthalpy of coal, which needs to be balanced with a suitable amount of heat delivered to pyrolysis stage and high final reaction temperature. The share of formation enthalpy in heat demand for pyrolysis is almost 68%.

In the case of coal processing by SES technology, the energy balance shows that the values of both parameters are comparable. This is a result of much lower formation enthalpy of coal than in a Shell case and lower final temperature of the reaction. However what is relevant is that the share of formation enthalpy is still substantial, amounting to almost 40% of heat demand for pyrolysis stage.

In the case of biomass processing heat demand for pyrolysis is close to that for the SES process. However, this is achieved at a very high value of enthalpy of formation, which is almost fivefold greater (−4746.8) kJ/kg. It means that in the thermal decomposition process some exothermic reactions take place to an extent greater than in the case of coal. This effect covers heat demand for the compensation of formation enthalpy. On the other side, the heat demand for gasification is much higher than in the SES case due to the highly endothermal reactions of steam-based gasification. As presented, the heat demand for a process is mainly gasification reaction driven. It should be also noted that without formation enthalpy the energy balance of pyrolysis would deliver a negative value of the heat of pyrolysis and the process would be self-sustained in terms of an internal heat source. However, this is not the case in a real situation.

Concluding, it should be stated that thermodynamic analysis of fuel gasification needs to be performed with a good knowledge of enthalpy of formation and an in depth understanding of the process. It is valuable to analyse it in terms of a two-stage process, namely: pyrolysis and gasification reactions. This delivers crucial information on the energy balance in subsequent stages of the fuel conversion.