Abstract

The purpose of this research was to assess the development potential of cities and municipalities in Wałbrzych County, approached from the perspective of social, economic and environmental potential. Comparisons were performed for the periods 2002–2004 and 2016–2018. The following problem questions were formulated in the study: Which strategic goals can currently act as incentives for taking action in the analysed post-industrial areas, and for which ones should development be particularly strengthened? What development direction should be taken by individual municipalities in Wałbrzych County? The research covering the development potential of the municipalities was conducted using the multidimensional analysis method, and the similarities in municipal potential were analysed taking into account a comparison of distances between individual diagnostic variables. Among the analysed municipalities, in terms of social, economic and environmental potential, Szczawno-Zdrój and Czarny Bór achieved the best results, and Boguszów Gorce ranked the worst. In some municipalities, a noticeable increase in social potential (Jedlina-Zdrój, Mieroszów, Walim) or economic potential (Jedlina-Zdrój) was observed, and a significant decline in economic potential in Stare Bogaczowice was seen. As a result of the research, the following was established: the policies of municipal authorities have to focus on improving the living conditions of residents; the crucial factors are opening new jobs, providing appropriate living conditions and services and offering diverse sports and tourism options. Efforts should be made to take advantage of the inherent potential in the area, also by highlighting the preserved post-industrial buildings and constructions.

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Foundations of Research Concept

Integrating social, economic and environmental phenomena remains the basis for developing an integrated order to create a system of strategic goals related to social, economic, environmental, institutional and political issues. That can be implemented through social, economic and cultural capital, as well as protection of the natural environment. When managing local development, local governments follow the statutory legal regulations that provide tools for influencing the local environment. Management focused on meeting the needs and aspirations of society requires formulating economic, environmental and social goals. The latter are related to the desire to improve living conditions, which will determine the standards of residents’ current life and their individual development perspectives [1].

The interdisciplinary approach to research is widely used in relation to making investment or political decisions. In numerous instances, policymakers and funding agencies call for researchers to address the grand societal challenges of globalized economic, ecological and demographical changes [2,3]. According to Reed et al., focusing efforts on only a single challenge may result in negative social or environmental outcomes [4].

Therefore, it is important to consider the problem of economic transformations much more extensively, as dictated by the contemporary problems of environmental protection in the context of energy technology, in addition to social and economic development.

As noted by Hełdak and Raszka [5], after Kozłowski [6] and Pęski [7], planning is one of the most important tools in the management process, is also used as a tool to form the future image of a country or a region, and, in the case of Poland, is decisive in terms of the quality of people’s lives and the functioning of the natural environment.

The decisions made locally and at higher levels of government should consider at least the environmental, social and economic aspects that are addressed in the presented research.

1.2. Effects of State Policy

The systemic transformation initiated in Poland in 1989 created new development opportunities; however, in some regions of the country, including the Wałbrzych region (part of the Lower Silesia Voivodship), it contributed to the decline of the leading industries [8]. The economic recession in the Wałbrzych region was aggravated by the closure of hard coal mines, which were the primary places of employment for the local community. The last mine was closed in 1997, and the entire restructuring process took only five years.

According to Buczak [9], the transformations that took place in Wałbrzych after the mines closed caused chaos in their initial phase; both the society and city authorities found it difficult to function in the new reality, while the city, with a growing unemployment rate and social dissatisfaction, was perceived as a black spot on the map of Poland, the centre of social pathology.

Economic transformations, including high levels of unemployment, are directly related to the deterioration of the quality of life of local residents. Along with the collapse of the economy, many people were forced to migrate in order to search for work and many families required financial support from the state, and the consequences of political transformation are still experienced today. The influence of the extractive industry is well described in the source literature. Based on their research, Karakaya and Nuur [10] stated that the environmental effects of mining have been a key topic in academic discourse for decades [11,12].

There is a noticeable trend towards encouraging mining companies to take the necessary remedial actions in connection with the closure of mines and to monitor the situations in local communities. It is important to focus on whether the existing restructuring plans fully address the environmental, social and economic conditions in terms of providing care and opportunities for relocated workers, and regarding the implications for government and other actors at all levels [13].

According to Solomon et al. [14], the social dimension of the extractive industry is increasingly recognized as essential to business success; however, it remains the least understood aspect of the business concept of sustainable development, the “triple bottom line” of economy, environment and society.

1.3. Quality of Life in Research

Research covering the differentiation of living conditions makes a distinction between the standard of living, which is a reflection of the degree of fulfilment of material needs, and quality of life, which results from the level of satisfaction obtained from various spheres of life or areas of activity [15,16,17,18,19]. Quality of life is an interdisciplinary concept referring to many different aspects, including the condition of the natural environment and owning material and non-material goods [20,21,22].

Research addressing quality of life not only can be useful for exploration-oriented purposes in terms of infrastructure, but also can be used for better planning and assessment of effectiveness regarding implemented social and economic policies, e.g., monitoring the use of financial resources. The multifaceted nature of the quality of life concept can be reflected in statistical measurements [23] using various indicators, including material living conditions (e.g., indicators of poor sanitary conditions) and the environment quality in residential areas (e.g., exposure to excessive noise and pollution, satisfaction with recreational and green areas). Many of these indicators fall within the scope of those used to assess sustainable development [24].

Various diagnostic variables defined by the indicators of social, economic and environmental development should be taken into account within the framework of broadly understood living conditions.

The purpose of this research was to assess the development potential of cities and municipalities of Wałbrzych County, approached from the perspective of social, economic and environmental potential. Poland faces the challenge of more mines being closed, and this research and the point of view presented in the discussion highlight the problems accompanying the economic transformations. Changes in energy industry policies will affect other regions of Poland where the energy industry is based on coal mining in the same way. In this context, this research could have national impact. An important element of the research is highlighting the residents’ quality of life in areas affected by the economic turndown resulting from the country’s political transformation and entering the free market economic system.

2. Materials and Methods

The spatial scope of the research covers an area in Lower Silesia, Poland, in the region of the former Wałbrzych Voivodship. All municipalities located in Wałbrzych County were selected for analysis: urban: Boguszów-Gorce, Jedlina-Zdrój and Szczawno-Zdrój; urban–rural: Głuszyca and Mieroszów; and rural: Czarny Bór, Stare Bogaczowice and Walim. Before the period of systemic transformation, this region was dominated by production, much of it dating back to the period before the Second World War. At the end of the 1980s, the period of industrial development in Poland came to an end.

In the studied area, excessively developed industry, characterised by inadequate sector structure and technological underdevelopment, ceased to be the leading development factor [25]. In addition, the closure of hard coal mines resulted in high unemployment rates and the depopulation of cities around Wałbrzych. The conducted analyses show the negative socio-economic effects of the collapse of many industries in the region. In general terms, the restructuring process brought about catastrophic economic consequences, although they could be perceived as beneficial for the natural environment [26,27,28].

The reclamation of post-mining areas, including the management of mining waste dumps, remains a significant problem in the Wałbrzych region, and the return of some municipalities to the pre-transformation level of development turned out to be a long-term process and still has not been accomplished.

The authors of the study put forward the following problem questions:

- What is the current social, economic and environmental potential of Wałbrzych County?

- Which strategic goals can currently act as incentives for action in the studied post-industrial areas, and for which ones should development be particularly strengthened?

- What development direction should be taken by individual municipalities in Wałbrzych County?

The research addressing the development potential of the municipalities was carried out using a multidimensional analysis method, zero unitarization. It allows comparisons of objects described by diagnostic variables of different nature. The method normalizes these variables and creates a synthetic variable, which enables the analysed objects to be ordered according to it.

The normalization of diagnostic variables is performed in line with the following formulas: For diagnostic variables that have a positive impact on the analysed phenomenon (stimulants):

For variables having a negative impact on the analysed phenomenon (destimulants):

where i = 1, 2, …, r and j = 1, 2, …, s; r is the number of objects and s is the number of diagnostic variables.

The synthetic variable (indicator) for the ith object is determined according to the following formula:

Next, the value of U can be determined:

Further, the categories of objects can be established as follows:

I. Objects with the highest indicator values:

II. Objects with average indicator values:

III. Objects with the lowest indicator values:

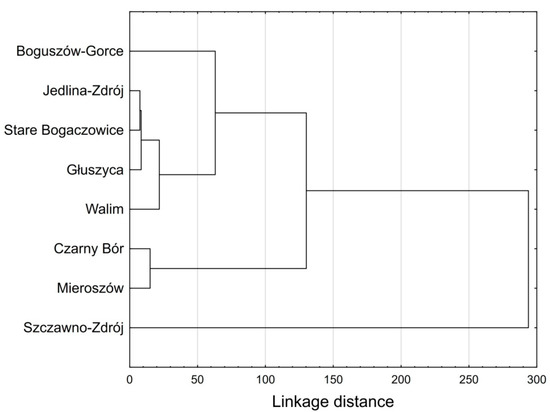

In addition to determining the total potential indicator, the similarities in municipal potential were also examined by comparing the distances of individual diagnostic variables. The agglomeration method was used, which creates a tree diagram that allows grouping the analysed objects into clusters. Euclidean distance was applied as the distance measure and Ward’s algorithm as the clustering method.

In determining the measures and distances, reference was made to the source literature [29,30] and subsequent research using the above-mentioned methods [31].

Most of the variables were taken directly from the Local Data Bank of Statistics Poland [32], which confirms their credibility, and only a few were calculated based on the same data parameters, e.g., some variables were defined per capita. The zero unitarization method was presented in an Excel spreadsheet.

The calculations were performed for standardized variables (TIBCO Software Inc.) [33].

The diagnostic variables that were included in the research are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Diagnostic variables adopted in the research.

The share of registered unemployed in the working age population was referred to as a destimulant, and the remaining variables as stimulants.

The research was carried out for the present period, taking into account the average diagnostic parameters from 2016–2018 and the beginning of the 21st century and the average parameters from 2002–2004. The averaging was performed because of certain variability over the years, primarily regarding the financial parameters. For the period 2002–2004, because there were no data, the following variables were not taken into account: employed per 1000 residents, expenditure on tourism per 1 resident and the length of bike paths. The characteristics of the variables used in the calculations covering the period 2016–2018 compared to the data of the Lower Silesia Voivodship and the entire country are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of variables included in research methods against the background of data from Lower Silesia Voivodship and the entire country.

A certain limitation in the research was the lack of access to some data referring to the whole country; these data were not published at the time of the research. It was not possible to determine the position of the analysed municipalities against the background of Poland in relation to some of the variables, but this did not affect the essence of the research.

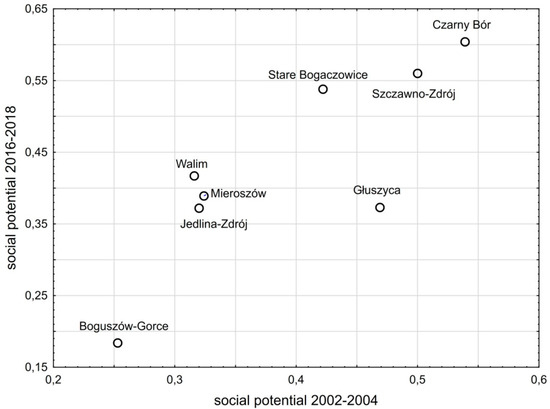

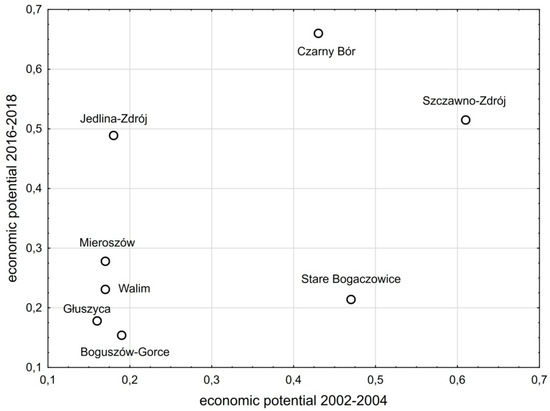

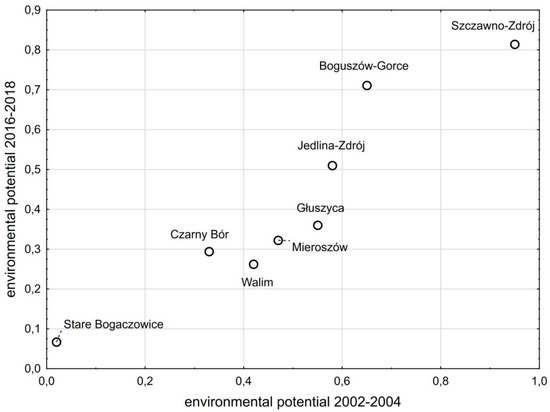

In order to better illustrate which municipalities recorded strengthened development potential in relation to other municipalities and in which ones this potential declined, scatter plots were prepared showing the indicator of potential for 2002–2004 vs. 2016–2018.

3. Results

In order to identify municipal development potential, the research findings were analysed. For each diagnostic variable, its least favourable state (for stimulants it is min x” and for destimulants it is max x”) has a value of zero. The state considered the most favourable (for stimulants it is max x’ and for destimulants it is min x’) has the highest value in the variability range of the normalized variables, i.e., unity [34,35,36,37].

The established indicators of social development potential in the municipalities of Wałbrzych County are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Indicators of social development potential in municipalities of Wałbrzych County calculated using zero unitarization method.

Among the diagnostic variables, the following were analysed: birth rate; migration; share of pre-working age population; share of working age population; working population; unemployment rate; and expenditure on culture, health and education, and health care facilities. In terms of social potential, the two analysed periods 2002–2004 and 2016–2018, Boguszów-Gorce municipality performed very poorly, ranking last with values of 0.253 and 0.189, respectively. Considering the possible numerical value in the range [0, 1], the result achieved here is alarmingly low. Significantly worse indicators were recorded in the Głuszyca municipality, which dropped from third position in 2002–2004 (0.469) to sixth position in 2016–2018 (0.373). At the same time, two municipalities remained in the lead and continuously increased their social potential: Czarny Bór, with values of 0.539 and 0.604 in the two analysed periods, and Szczawno-Zdrój, with 0.5000 and 0.560.

In the next part of the research, the economic potential of Wałbrzych municipalities was analysed (Table 4).

Table 4.

Indicators of economic development potential for Wałbrzych County municipalities calculated using zero unitarization method.

The diagnostic variables adopted to assess economic development potential included expenditure by selected sectors of the municipal economy (e.g., residential housing management, transport and communication, tourism, and agriculture), revenues of municipal budgets, expenditure of municipal budgets, funding and co-funding EU programmes and projects, share of the municipal investment in the total expenditure of the municipal budget, the length of bike paths and economic entities. In this case, in both analysed periods, the municipalities of Szczawno-Zdrój and Czarny Bór achieved the best results, while Głuszyca and Boguszów-Gorce were rated the worst. The established indicators, and therefore also the ranking positions, changed in the analysed years.

The least significant changes when comparing 2002–2004 and 2016–2018 took place in terms of the environmental potential (Table 5). The highest indicator in both analysed periods was recorded in Szczawno Zdrój and Boguszów-Gorce.

Table 5.

Indicators of environmental development potential for Wałbrzych County municipalities calculated using zero unitarization method.

There was a certain stability in the assessment of environmental potential indicator results from, among others, variables that involve considerable resources and time to expand, e.g., sewage systems, water supply systems, gas pipelines and sewage treatment plants, and also from the implicit constant nature of some of the adopted features (e.g., share of forest area). The diagnostic variables adopted to assess environmental potential included expenditure on municipal management and environmental protection, water consumption, length of active sewage network, population using water supply network, population using sewage treatment plants, share of forest land in the total area of the municipality, population using gas vs. total population, and share of parks, lawns and housing estate green areas in the total area.

In the interval between the analysed periods, 2002–2004 and 2016–2018, no significant change in the ranking of individual municipalities was observed; however, a decline in potential was noticed in most of them.

The graphs in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the dispersion of social, economic and environmental potential of Wałbrzych municipalities for the periods 2002–2004 and 2016–2018. In terms of the social potential indicator, the most stable and best situation occurred in Czarny Bór and Szczawno-Zdrój, while Walim, Mieroszów and Jedlina-Zdrój remained close to each other.

Figure 1.

Scatter plot of social development potential in 2002–2004 vs. 2016–2018. Source: authors’ compilation based on bdl.stat.gov.pl (accessed on 30 October 2020) [32].

Figure 2.

Scatter plot of economic development potential in 2002–2004 vs. 2016–2018. Source: authors’ compilation based on bdl.stat.gov.pl (accessed on 30 October 2020) [32].

Figure 3.

Scatter plot of environmental development potential in 2002–2004 vs. 2016–2018. Source: authors’ compilation based on bdl.stat.gov.pl (accessed on 30 October 2020) [32].

The municipalities presenting the highest economic potential in 2016–2018 were, in the following order, Czarny Bór, Szczawno Zdrój and Jedlina Zdrój; the potential significantly increased since the beginning of the century in Czarny Bór and Jedlina Zdrój (Figure 2). Boguszów-Gorce, Głuszyca, Mieroszów and Walim, whose economic potential was relatively low, show a clear concentration in both analysed periods.

The dispersion indicator of environmental development potential ranks Szczawno-Zdrój in the best position, and shows improvement in Boguszów-Gorce and a lower assessment in Jedlina-Zdrój, Głuszyca, Mieroszów and Walim.

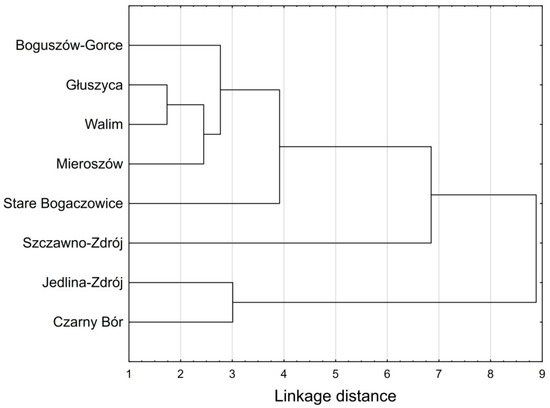

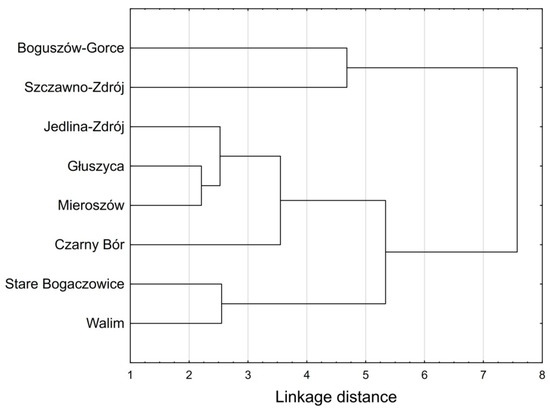

Further analyses using the agglomeration method confirmed the previously obtained results (Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 4.

Tree diagram of social potential 2016–2018. Source: authors’ compilation based on bdl.stat.gov.pl (accessed on 30 October 2020) [32].

Figure 5.

Tree diagram of economic potential 2016–2018. Source: authors’ compilation based on bdl.stat.gov.pl (accessed on 30 October 2020) [32].

Figure 6.

Tree diagram of environmental potential 2016–2018. Source: authors’ compilation based on bdl.stat.gov.pl (accessed on 30 October 2020) [32].

The agglomeration method (Figure 4) shows that the social potential parameters of Szczawno-Zdrój included in the research differ significantly from the parameters of other municipalities. The municipalities most similar in this respect are Jedlina Zdrój, Stare Bogaczowice and Głuszyca. Taking into account the cluster analysis tree in terms of economic potential (Figure 5), it was found that Czarny Bór and Jedlina Zdrój constitute a separate group. As regards the environmental potential indicator, the highest value in both analysed periods was achieved by Szczawno Zdrój and Boguszów-Gorace. They also constitute a separate cluster in the agglomeration method (Figure 6). Stare Bogaczowice and Walim were similar in terms of environmental parameters, characterised by the lowest Q indicator.

4. Discussion

4.1. Current Social, Economic and Environmental Potential of Wałbrzych County

Having analysed the diagnostic variables, it can be concluded that the position of Wałbrzych County municipalities is usually worse compared to the average values achieved for the entire Lower Silesia Voivodship area. The shutdown of some production plants and the complete closure of hard coal mines resulted in the aggravation of social problems in these municipalities. In recent years, a lower average birth rate per 1000 people (−5.2) has been observed in this area compared to Lower Silesia and the entire country (−1.4 and 0.5). Other diagnostic features confirm the unfavourable demographic structure of the discussed municipalities and the small share of employed people in the total population. The number of employed people per 1000 inhabitants raises concerns and suggests the need to take up remedial measures; on average, only 118 people per 1000 residents work in the municipalities surrounding the city of Wałbrzych, compared to 389 people per 1000 residents in Lower Silesia.

Detailed research findings confirm that the social development potential of the municipalities is alarmingly low. Boguszów-Gorce remains the worst-ranked municipality in this respect. It is also the only municipality which received the lowest third category ranking. Together with the low economic potential, this assessment translates into a low quality of life for residents of this municipality. However, Boguszów Gorce has an advantage in the form of environmental potential (rank I), which can be used in further functional transformations.

The next municipalities in the group featuring low social potential are Jedlina Zdrój, Mieroszów, Walim and Głuszyca.

The municipalities characterised by low economic potential also include Głuszyca, Mieroszów, Stare Bogaczowice and Walim. Thus, some municipalities that present unfavourable social potential are also characterized by unfavourable economic potential. Further analysis also revealed that the natural potential of municipalities such as Stare Bogaczowice, Walim, Mieroszów and Głuszyca is not highly rated.

Concerns are raised by the fact that the same municipalities appear to be among the worst assessed in terms of social, economic and environmental potential.

4.2. Identifying Main Municipal Strategic Goals and Tasks Faced by Local Authorities Based on the Conducted Research

In accordance with the research conducted by Stacherzak et al. [38] on functional transformations, since 1996, municipalities have been strengthening the function of industrialization developed for tourism purposes, almost without agriculture (where agriculture is not of great importance).

The process of transformations is slow and difficult. Most likely, in the next several dozen years, it will not be possible to restore the population back to the level prior to the transformation period (before 1991). It is crucial to focus on taking action and improving the quality of life of the population at the current level. The actions for individual municipalities are listed below.

Municipalities: Boguszów Gorce, Jedlina-Zdrój, Mieroszów, Stare Bogaczowice, Walim, Głuszyca:

- Retain young people entering the labour market locally by creating jobs, providing facilities for families with children and developing sports and recreational offers for various age groups.

- Introduce the principles of planned housing management in the municipal housing stock through the flat replacement programme, and renovation and demolition of decapitalised buildings.

- Increase municipal activity of obtaining EU funds as well as funds from external sources in order to stimulate the economic activity of residents in the region.

- Promote and advertise the entire Wałbrzych region in Poland along with developing tourist and accommodation facilities, and create opportunities to participate in specific events and make unique tourist attractions available for sightseeing.

The municipalities of Szczawno-Zdrój and Czarny Bór are ranked best in terms of social and economic potential. Additionally, Szczawno Zdrój has high environmental potential. The main strategic goals include the following:

- Strive to maintain the municipal development potential.

- Further develop services for the population and care for municipal economic development, including job retention.

4.3. Further Directions for the Development of Municipalities Based on Their Potential

Economic processes and sustainability remain crucial from the perspective of broader development processes taking place in the economy [25,39,40], including the aspect of providing the population with an appropriate standard of living and preventing excessive migration. These municipalities, according to our assessment, do not present significant potential for environmental development; however, in their area, there are underground military buildings from the Second World War (Osówka Complex, Underground City, Walim Adits) and monuments of architecture and technology (Grodno Castle, a water dam on the Bystrzyca River, the Bystrzyca Railway). The municipalities have many attractions that allow the development of tourism; they are surrounded by the beautiful landscape of the Sowie, Wałbrzyskie and Kmienne Mountains, but the activity of the local community is at a lower level than the rest of the Lower Silesia region. Local resources play a significant role in theoretical thinking about development; however, in practice they are difficult to identify [41].

Although the main determinant of quality of life is in the form of psychological factors [42], it is also closely related to other factors. Quality of life includes, among other things, economic conditions [43], individual expectations, participation in social life [44], place and conditions of residence [45], quality of the environment in which people live [46,47] and the degree of satisfaction of various human needs [48,49].

The good social, economic and environmental conditions of the Szczawno Zdrój municipality result from its location, environmental value, including medicinal waters used in spa treatment, and access to green areas, as well as caring for the city’s image. The good ranking of Czarny Bór municipality is explained by the location of the Special Economic Zone within its area and the investments carried out there.

It can be suggested that using the inherent potential in the discussed area should determine the direction of this region’s development; apart from tourism and recreation, the focus should also be on investing in rebuilding and developing industrial production. The mining industry used to be the driving force behind the economic development of Wałbrzych County, and today it should be industry based on new technologies in order to develop the potential of the local community. The establishment of the Wałbrzych Special Economic Zone allowed for the passivity and dependence on coal monoculture to be partially overcome [50]. This trend is developing simultaneously with the sector of small and medium-sized enterprises.

4.4. Limitations and Further Development of the Research

Certain limitations in reaching the diagnostic variables covering the entire area of the country appeared in the study. The authors plan to continue the research, focused on updating the analysis regarding the development strategies of individual municipalities and of Wałbrzych County. The planned research will refer to the observations and findings on the status and potential of the municipalities covered by this study. In further work, the authors would like to show compliance with strategic development goals included in the development strategies of individual municipalities with the current social, economic and environmental situation, and to identify the areas (strategic goals) which require changes as a result of the research findings.

5. Conclusions

The conducted research allowed us to answer the problem questions and formulate the following final conclusions.

The research revealed that the social potential of some municipalities in Wałbrzych County is alarmingly low, and a return to the level of development before the transformation has proved to be a long-term process and has not yet been reached.

Among the analysed municipalities, in terms of social, economic and environmental potential, Szczawno-Zdrój and Czarny Bór achieved the best results, and Boguszów Gorce was ranked the worst. In some municipalities, a noticeable increase in social potential (Jedlina-Zdrój, Mieroszów, Walim) and economic potential (Jedlina-Zdrój) was observed, and a significant decline in economic potential in Stare Bogaczowice was also noticeable.

The policies of municipal authorities have to focus on improving the living conditions of residents. Monitoring alone, without taking any specific measures, could result in significant depopulation of the area.

Municipal authorities should support the development of local initiatives that take advantage of the beauty of nature and technical monuments.

In the analysed municipalities of Wałbrzych County, special care should be taken to improve the living conditions of residents (to strengthen economic and social potential), which may have a significant impact on whether or not young people decide to stay there after graduation. The crucial elements are to open new jobs provide appropriate living conditions and services to allow taking up employment while caring for children, and to offer diverse sports and tourist options.

The analysis shows that the vast majority of municipalities offer great environmental potential. Efforts should be made to use the inherent potential in the area, also by highlighting preserved post-industrial buildings and constructions.

Beyond any doubt, the Wałbrzych region requires systemic support from the state to stop the depopulation of municipalities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.R. and H.D.; methodology, B.R. and M.H.; software, B.R.; validation, B.R., M.H. and H.D.; formal analysis, B.R., M.H. and H.D.; investigation, B.R; resources, B.R. and M.H.; data curation, H.D.; writing—original draft preparation, B.R. and M.H.; writing—review and editing, B.R and M.H.; visualization, H.D.; supervision, B.R.; project administration, M.H.; funding acquisition, B.R and M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research and the publication were financed under the Leading Research Groups support project from a subsidy increased for the period 2020–2025 in the amount of 2% of the subsidy referred to Art. 387 (3) of the Law of 20 July 2018 on Higher Education and Science, obtained in 2019. The open-access publication fee was financed under the Leading Research Groups support project from the subsidy increased for the period 2020–2025 in the amount of 2% of the subsidy referred to Art. 387 (3) of the Law of 20 July 2018 on Higher Education and Science, obtained in 2019.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data analysed in this study are subject to the following licenses/restrictions: Some of the datasets presented in this study are included in the paper. Some of the data can be obtained by contacting the authors. Requests for access to these datasets should be directed to Maria Hełdak: maria.heldak@upwr.edu.pl.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Oleszko-Kurzyna, B. Jakość życia a procesy zarządzania rozwojem gmin wiejskich [Quality of life vs. management processes of rural municipalities development]. In Polityka Społeczna Wobec Problemu Bezpieczeństwa Socjalnego w Dobie Przeobrażeń Społeczno-Gospodarczych [Social Policy towards the Problem of Social Security in the Age of Socio-Economic Transformations]; Rączaszek, A., Koczur, W., Eds.; University of Economics in Katowice: Katowice, Poland, 2014; Volume 179, pp. 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Langfeldt, L.; Godø, H.; Gornitzka, A.; Kaloudis, A. Integration modes in EU research: Centrifugality versus coordination of national research policies. Sci. Public Policy 2012, 39, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, D. Integrating social sciences and humanities in interdisciplinary research. Palgrave Commun. 2016, 2, 16036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, J.; Van Vianen, J.; Deakin, E.L.; Barlow, J.; Sunderland, T. Integrated landscape approaches to managing social and environmental issues in the tropics: Learning from the past to guide the future. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2016, 22, 2540–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hełdak, M.; Raszka, B. Evaluation of the Local Spatial Policy in Poland with Regard to Sustainable Development. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2013, 22, 395–402. [Google Scholar]

- Kozłowski, S. The Future of Eco-Development; KUL Publishing: Lublin, Poland, 2005; Volume 197, p. 586. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Pęski, W. Zarządzanie Zrównoważonym Rozwojem Miast [Managing the Sustainable Development of a City]; Wydawnictwo Arkady: Warszawa, Poland, 1999; Volume 20, p. 294. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Hełdak, M. Przemiany funkcjonalne obszarów wiejskich Sudetów po integracji z Unią Europejską [Functional Transformations of Rural Areas of the Sudeten after the European Union Integration]. In Infrastruktura i Ekologia Terenów Wiejskich [Infrastructure and Ecology of Rural Areas]; No. 8/2008; The Kraków Branch of the Polish Academy of Sciences: Kraków, Poland, 2008; pp. 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Buczak, A. Centrum Nauki i Sztuki “Stara Kopalnia” w Wałbrzychu jako Przykład Rewitalizacji Obiektu Poprzemysłowego, Samorząd Terytorialny w Polsce z Perspektywy 25-lecia jego Funkcjonowania [The Science and Art Centre “Old Mine” in Wałbrzych as an Example of the Post-Industrial Facility Revitalization, Local Government in Poland from the Perspective of the 25th Anniversary of Its Functioning]; Laskowski, P., Ed.; Research Papers of Wałbrzych Higher Scholl of Management and Enterprise: Wałbrzych, Poland, 2015; Volume 33, pp. 33–52. Available online: http://www.pracenaukowe.wwszip.pl/prace/prace-naukowe-33.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Karakaya, E.; Nuur, C. Social sciences and the mining sector: Some insights into recent research trends. Resour. Policy 2018, 58, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappuyns, V.; Swennen, R.; Vandamme, A.; Niclaes, M. Environmental impact of the former Pb-Zn mining and smelting in East Belgium. J. Geochem. Explor. 2006, 88, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudka, S.; Adriano, D.C. Environmental impacts of metal ore mining and processing: A review. J. Environ. Qual. 1997, 26, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IIED. Breaking New Ground: Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development (MMSD). 2002. Available online: http://pubs.iied.org/9084IIED/ (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Solomon, F.; Katz, E.; Lovell, R. The Social Dimensions of Mining: Research, Policy and Practice Challenges for the Minerals Industry in Australia. Resour. Policy 2008, 33, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borys, T. Propozycja Siedmiu Typologii Jakości Życia [A Proposal of Seven Typologies of the Quality of Life]. In Gospodarka a Środowisko [Economy vs. Environment]; Research Papers of Wrocław University of Economics: Wrocław, Poland, 2008; Volume 9, pp. 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, M.; Feinstein, A.R. A Critical Appraisal of the Quality of Quality-of-Life Measurements. JAMA 1994, 272, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, R. The Quality of Life and the Environment. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 35, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Malina, A.; Zeliaś, A. Taksonomiczna analiza przestrzennego zróżnicowania jakości życia ludności w Polsce w 1994 r. [Taxonomic analysis of spatial differentiation in the quality of life of the population in Poland in 1994.]. Stat. Rev. 1997, 44, 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Uzzell, D.; Moser, G. Environment and quality of life. Rev. Eur. Psychol. Appl. 2006, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusterka-Jefmańska, M. Wysoka jakość życia jako cel nadrzędny lokalnych strategii zrównoważonego rozwoju [High quality of life as the primary goal of local sustainable development strategies]. Public Manag. 2010, 4, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Burckhardt, C.S.; Anderson, K.L. The Quality of Life Scale (QOLS): Reliability, Validity, and Utilization. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2003. Available online: http://www.hqlo.com/content/1/1/60 (accessed on 4 April 2021).

- Kucher, A.; Hełdak, M.; Kucher, L.; Raszka, B. Factors Forming the Consumers’ Willingness to Pay a Price Premium for Ecological Goods in Ukraine. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenka-Zganiacz, A. Jakość życia w badaniach ekonomicznych, społecznych i w statystyce publicznej [Quality of life in economic and social research and in public statistics]. In Pomiar Jakości Życia w Układach Regionalnych i Krajowych. Dylematy i Wyzwania [Measurement of the Quality of Life in Regional and National Systems. Dilemmas and Challenges]; Studies and Materials of the Faculty of Management and Administration of the Jan Kochanowski University: Kielce, Poland, 2017; Volume 21/3 (1), pp. 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- The Indicators of Sustainable Development for Poland. Team of Employees of the Statistical Office in Katowice with the Co-Participation of: Statistical Office in Kraków Statistical Office in Szczecin Analysis and Comprehensive Studies Department of CSO under the Management of Edmund Czarski. Ph.D. Thesis, Central Statistical Office, Katowice, Poland, 2011. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/cps/rde/xbcr/gus/as_Sustainable_Development_Indicators_for_Poland.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Parysek, J. Wewnętrzne i Zewnętrzne Uwarunkowania Transformacji Przestrzenno—Strukturalnej i Rozwoju miast Polski w końcu XX wieku. Przemiany bazy Ekonomicznej i Struktury Przestrzennej Miast pod red. Naukową Janusza Słodyczka [Internal and External Determinants of Spatial and Structural Transformation and the Development of Polish Cities at the End of the 20th Century. Changes in the Economic Base and Spatial Structure of Cities, ed. Janusz Słodyczka]; University of Opole: Opole, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Borówka, A. Stan i Perspektywy Wykorzystania Obiektów Poprzemysłowych w Wałbrzychu i Boguszowie-Gorcach [The Condition and Perspectives for Using Post-Industrial Facilities in Wałbrzych and Boguszów-Gorce]; Institute of Geography and Regional Development, University of Wrocław: Wrocław, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kosmaty, J. Wałbrzyskie Tereny Pogórnicze po 15 Latach od Zakończenia Eksploatacji Węgla [Wałbrzych Post-Mining Areas 15 Years after the Closure of Coal Mining]. Coal Min. Ecol. 2011, 6. Available online: https://www.polsl.pl/Wydzialy/RG/Wydawnictwa/Documents/kwartal/6_1_13.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Wójcik, J. Przemiany Wybranych Komponentów Środowiska Przyrodniczego Rejonu Wałbrzyskiego w Latach 1975–2000 w Warunkach Antropopresji, ze Szczególnym Uwzględnieniem Wpływu Przemysłu [Transformations of the Selected Components of the Wałbrzych Region Natural Environment in the Years 1975–2000 in the Conditions of Anthropopressure, with Particular Emphasis on the Impact of Industry]. Scientific Thesis, The Institute of Geography and Regional Development of the University of Wrocław 21 [Habilitation Degree], University of Wrocław, Wrocław, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, J.H. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1963, 58, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkutnik, W.; Sączewska-Piotrowska, A.; Hadaś-Dyduch, M. Metody Taksonomiczne z Programem STATISTICA; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Katowicach: Katowicach, Poland, 2015; p. 144. [Google Scholar]

- Basiura, B. Metoda Warda w zastosowaniu klasyfikacji województw Polski z różnymi miarami odległości [The Ward method in the application for classification of Polish voivodeships with different distances]. In Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu [Research Papers of Wrocław University of Economics]; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu: Wrocławiu, Poland, 2013; pp. 209–216. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Poland, Local Data Bank. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/BDL/start (accessed on 4 September 2019).

- TIBCO Software Inc. Statistica (Data Analysis Software System), Version 13. 2017. Available online: http://statistica.io (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Kukuła, K.; Bogocz, D. Zero Unitarization Method and its Application in Ranking Research in Agriculture. Econ. Reg. Stud. 2014, 7, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kukuła, K. Metoda unitaryzacji zerowej na tle wybranych metod normowania cech diagnostycznych [Zero unitarization method at the background of selected methods for the diagnostic features normalization]. Acta Sci. Acad. Ostroviensis 1999, 5–31. Available online: http://bazhum.muzhp.pl/ (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Kukula, K. Metoda Unitaryzacji Zerowanej; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2000; Volume 71. [Google Scholar]

- Kukuła, K. Badania Operacyjne w Przykładach i Zadaniach; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2004; Volume 289. [Google Scholar]

- Stacherzak, A.; Hełdak, M. Borough Development Dependent on Agricultural, Tourism, and Economy Levels. Sustainability 2019, 11, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybyła, K. Employment structure transformations in large polish cities. In Hradec Economic Days; Jedlička, P., Ed.; University of Hradec Kralove: Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic, 2018; Volume 8, pp. 196–205. [Google Scholar]

- Przybyła, K.; Kachniarz, M.; Hełdak, M. The Impact of Administrative Reform on Labour Market Transformations in Large Polish Cities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surnacz, M. Zasoby lokalne jako potencjały rozwoju lokalnego w dokumentach strategicznych na przykładzie wybranych gmin wiejskich województwa śląskiego [Local resources as the potential for local development in the strategic documents based on selected rural municipalities of the Silesian Voivodship]. Stud. Rural. Areas 2017, 46, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.W.; Avis, N.E.; Assman, S.F. Distinguishing between quality of life and health status in quality of life research: A meta-analysis. Qual. Life Res. 1999, 8, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sompolska-Rzechuła, A. Jakość życia jako kategoria ekonomiczna [Quality of life as an economic category]. Folia Pomer. Univ. Technol. Stetin Oeconomica 2013, 301, 127–140. Available online: http://foliaoe.zut.edu.pl/pdf/files/magazines/2/38/457.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Papuć, E. Jakość życia—definicje i sposoby jej ujmowania [Quality of life—definitions and presentation methods]. Curr. Probl. Psychiatry 2011, 12, 141–145. Available online: https://docplayer.pl/8578848-Jakosc-zycia-definicje-i-sposoby-jej-ujmowania-ewa-papuc.html (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Campbell, A.; Converse, P.E.; Rogers, W.L. The Quality of American Life: Perception, Evaluation, and Satisfaction; Rasel Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Kusterka, M. “Audyt miejski” jako narzędzie pomiaru jakości życia w miastach europejskich [“City audit” as a tool to measure the quality of life in European cities]. In Gospodarka a Środowisko [Economy vs. Environment]; Borys, T., Ed.; Research Papers of Wrocław University of Economics: Wrocław, Poland, 2008; Volume 22, pp. 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, S.; Orley, J. Quality of life assessment. The World Health Organization perspective. Eur. Psychiatry 1997, 12 (Suppl. S3), 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak, E. Jakość życia w polskich województwach—analiza porównawcza wybranych regionów [Quality of life in Polish voivodships—Comparative analysis of selected regions]. Soc. Inequal. Econ. Growth 2016, 48, 66–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobiasz-Adamczyk, B. Jakość życia w naukach społecznych i medycynie [Quality of life in social sciences and medicine]. Art Treat. 1996, 2, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zakrzewska-Półtorak, A. Problemy rozwoju Wałbrzycha i ich znaczenie dla rozwoju województwa dolnośląskiego [Problems of Wałbrzych development and their impact on Lower Silesia development]. Bibl. Reg. 2010, 10. Available online: https://dbc.wroc.pl/Content/35006/Zakrzewska-Poltorak_Problemy_Rozwojowe_Walbrzycha_i_Ich.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).