Thermochemical Energy Storage Based on Carbonates: A Brief Overview

- Carbonate systems have a high theoretical energy density, which allows for maximizing the storage capacity. It is worth highlighting, in this case, the systems based on CaCO3/CaO, SrCO3/SrO and MgCO3/MgO (~3–4 GJ/m3). These values are ~10 times higher than sensible heat storage systems (i.e., molten salts); despite this, it must be considered that the systems are more complex, requiring tanks for the storage of products (solid and gas/liquid). Thus, the real energy density of carbonate TCES systems depends on material properties, reaction efficiency and process configuration [6].

- Carbonates are widely available, usually cheap, and environmentally friendly. Calcium carbonate stands out, one of the most abundant materials on the planet, and with a large-scale price of around EUR 10/ton (two orders of magnitude lower than the price of solar salts).

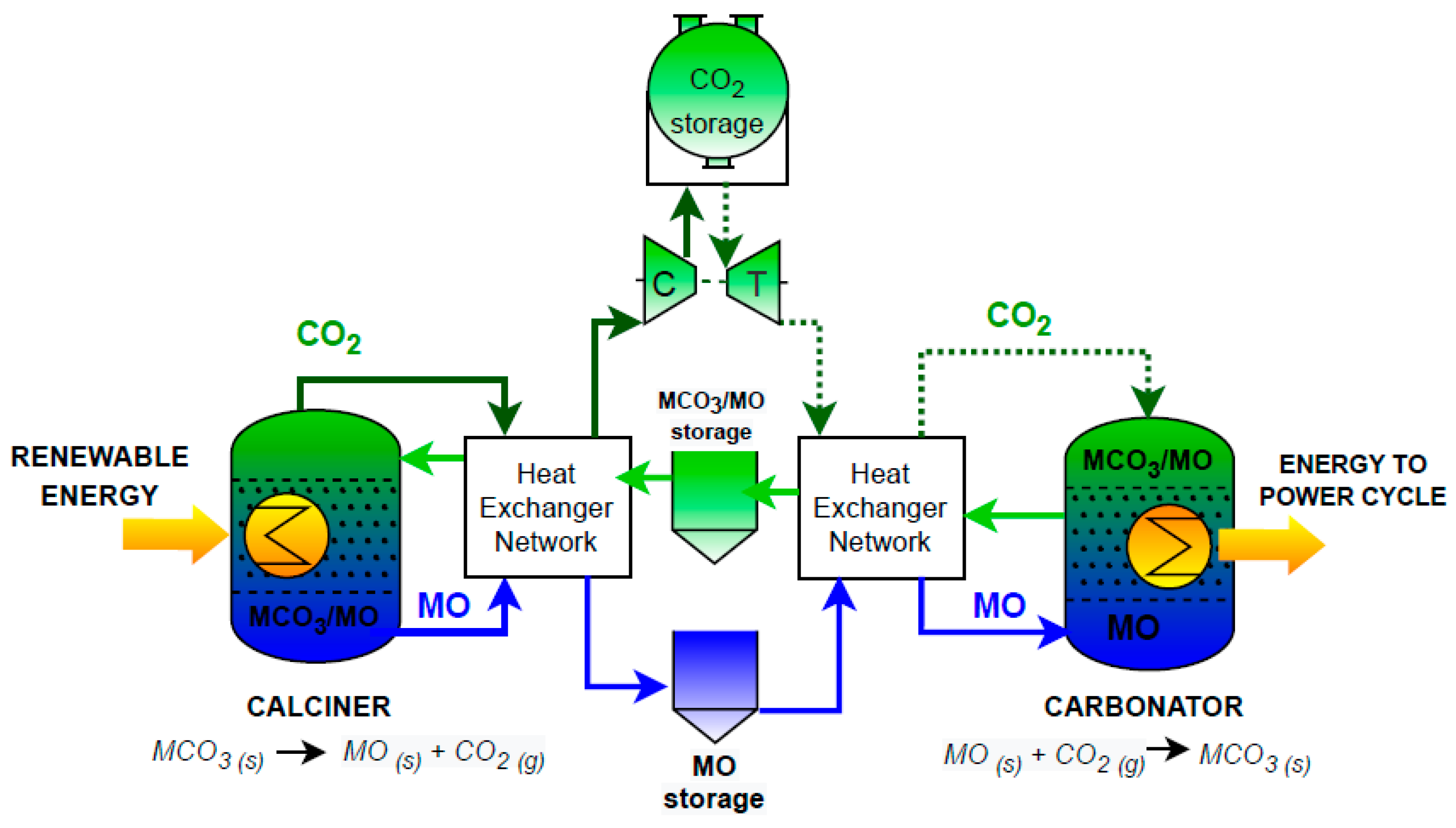

- A key advantage over molten salt systems is the ability to store products at ambient temperature, which significantly reduces electricity consumption and eliminates the risks derived from the solidification of salts. This makes the system more flexible, increasing the energy storage capacity in days or even weeks, although it also increases the complexity of the heat exchangers network when it comes to recovering the sensible heat of the materials at the exit of the endothermic reactor (high temperature).

- Several carbonates have a high-turning temperature, which gives them the ability to release heat through the exothermic reaction at temperatures higher than 900 °C and, therefore, the possibility of integrating with high-efficiency power cycles, such as combined cycles, supercritical Rankine cycles or Brayton Cycles. They stand out: SrCO3, BaCO3, PbCO3 and CaCO3.

- Regarding the materials and equipment, carbonate TCES is based on solid–gas reactions, which gives the system an extra degree of complexity compared to systems based on sensible heat. Nevertheless, in the case of CaCO3/CaO TCES, there is a closeness with the cement industry (reactors, vessels, cyclones, etc.), which facilitates the deployment of the technology.

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ortiz, C.; Valverde, J.M.; Chacartegui, R.; Perez-Maqueda, L.A.; Giménez, P. The Calcium-Looping (CaCO3/CaO) process for thermochemical energy storage in Concentrating Solar Power plants. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 113, 109252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, L.; Abanades, S. Evaluation and performances comparison of calcium, strontium and barium carbonates during calcination/carbonation reactions for solar thermochemical energy storage. J. Energy Storage 2017, 13, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare Ghorbaei, S.; Ale Ebrahim, H. Carbonation reaction of strontium oxide for thermochemical energy storage and CO2 removal applications: Kinetic study and reactor performance prediction. Appl. Energy 2020, 277, 115604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahon, D.; Claudio, G.; Eames, P. An Experimental Study of the Decomposition and Carbonation of Magnesium Carbonate for Medium Temperature Thermochemical Energy Storage. Energies 2021, 14, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alovisio, A.; Chacartegui, R.; Ortiz, C.; Valverde, J.M.; Verda, V. Optimizing the CSP-Calcium Looping integration for Thermochemical Energy Storage. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 136, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, C.; Romano, M.C.; Valverde, J.M.; Binotti, M.; Chacartegui, R. Process integration of Calcium-Looping thermochemical energy storage system in concentrating solar power plants. Energy 2018, 155, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, C.; Valverde, J.M.; Chacartegui, R.; Pérez-Maqueda, L.A.; Gimenez-Gavarrell, P. Scaling-up the Calcium-Looping Process for CO2 Capture and Energy Storage. KONA Powder Part. J. 2021, 38, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benitez-Guerrero, M.; Valverde, J.M.; Perejon, A.; Sanchez-Jimenez, P.E.; Perez-Maqueda, L.A. Low-cost Ca-based composites synthesized by biotemplate method for thermochemical energy storage of concentrated solar power. Appl. Energy 2018, 210, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ortiz, C. Thermochemical Energy Storage Based on Carbonates: A Brief Overview. Energies 2021, 14, 4336. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144336

Ortiz C. Thermochemical Energy Storage Based on Carbonates: A Brief Overview. Energies. 2021; 14(14):4336. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144336

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrtiz, Carlos. 2021. "Thermochemical Energy Storage Based on Carbonates: A Brief Overview" Energies 14, no. 14: 4336. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144336

APA StyleOrtiz, C. (2021). Thermochemical Energy Storage Based on Carbonates: A Brief Overview. Energies, 14(14), 4336. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144336