Public Acceptance of Renewable Energy Sources: a Case Study from the Czech Republic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and the Survey

2.1.1. Measures of Opinions on Renewable Energy Sources

- “Do you think it is possible to replace electricity generation from the conventional sources (such as coal-fired or gas-fired power plants, nuclear power plants or large hydroelectric power plants) by generating electricity from wind, solar radiation, and biomass combustion?” (1—it is definitely possible to replace it, 2—it is rather possible to replace it, 3—it is rather not possible to replace it, 4—it is definitely not possible to replace it)

- “What do you think is the situation in our country concerning the use of renewable energy sources?” (1—very good, 2—rather good, 3—rather bad, 4—very bad) (Sociologický ústav, Akademie věd ČR, 2019 [42]).

2.1.2. Measures for the Exposition to Sources of Information on a Country Level Social Life

2.1.3. Measures of Opinions on Environment

- “In your opinion, how much does the Czech Republic care of environmental protection?” 1—too much, 2—adequately, 3—too little

- “In your household, do you save energy and water for environmental reasons?” 1—always, 4—never, 4-point scale

- “Do you have enough information on the state of the environment in the Czech Republic?”, 1—sufficient information, 4—insufficient information, 4-point scale.

2.1.4. Measure of Worry about the Use of Nuclear Energy

2.1.5. Measures of Opinion on Living Standard and Life Satisfaction

- “Do you consider the standard of living of your household: 1—very good, 2—rather good, 3—neither good nor bad, 4—rather bad, 5—very bad”

- “How satisfied are you with your life?” 1—very satisfied, 5—very unsatisfied, 5-point scale

2.1.6. Social and Demographic Factors

2.2. Methods

- Info—stands for the exposition to a country’s level social life in the mass media and other sources of information (see Table 3);

- Env—stands for the environmental concerns (Table 4).

- Nu—stands for the level of fear of nuclear energy (Table 5)

- Age, Sex, Edu, Pol—stand for age, sex, education, and political orientation (right-left wing, 11-point scale) of the respondents respectively. The education variable was split into dummies for the elementary, secondary without state exam, secondary with state exam, and higher education. Higher education dummy was used as a reference variable.

2.3. Data Transformation—Inclusion of Ordinal Predictors to Regression Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sources of Information

3.2. Environmental Concerns

3.3. Concerns for Nuclear Energy

3.4. Standard of Living and Sociodemographic Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Newbery, D.; Pollitt, M.G.; Ritz, R.A.; Strielkowski, W. Market design for a high-renewables European electricity system. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 91, 695–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, A.; Scandurra, G. The impact of climate funds on economic growth and their role in substituting fossil energy sources. Energy Policy 2019, 129, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.; Snyder, B.; Henriques, E.; Reis, L. European offshore wind capital cost trends up to 2020. Energy Policy 2019, 129, 1364–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Renewable Energy Total, % of Primary Energy Supply, 1974–2018. IEA World Energy Statistics and Balances: Extended World Energy Balances. 2020. Available online: https://data.oecd.org/energy/renewable-energy.htm (accessed on 6 March 2020).

- European Parliament. Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Promotion and use of Energy from Renewable Sources. COM (2008), 19. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52008SC0057 (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- Klessmann, C.; Nabe, C.; Burges, K. Pros and cons of exposing renewables to electricity market risks—A comparison of the market integration approaches in Germany, Spain, and the UK. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 3646–3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, M.; Del Río, P.; Montero, E.A. Assessing the benefits and costs of renewable electricity. The Spanish case. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 27, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Río, P.; Resch, G.; Ortner, A.; Liebmann, L.; Busch, S.; Panzer, C. A techno-economic analysis of EU renewable electricity policy pathways in 2030. Energy Policy 2017, 104, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Izquierdo, M.; del Río, P. Benefits and costs of renewable electricity in Europe. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 61, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Miera, G.S.; del Río González, P.; Vizcaíno, I. Analysing the impact of renewable electricity support schemes on power prices: The case of wind electricity in Spain. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 3345–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, L.J.; Hakvoort, R.J. The Question of Generation Adequacy in Liberalised Electricity Markets. INDES Working Paper No 5. 1 March 2004. Available online: http://aei.pitt.edu/11086 (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- Li, Z.; Yao, T. Renewable energy basing on smart grid. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Wireless Communications Networking and Mobile Computing (WiCOM) 2010, Shenzhen, China, 23–25 September 2010; pp. 1–4. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/5600862 (accessed on 19 March 2020).

- Siano, P. Demand response and smart grids—A survey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 30, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffre, F.; Gedge, R. Demand-side management for the smart grid. In Proceedings of the IEEE/IFIP Network Operations and Management Symposium Workshops, Osaka, Japan, 19–23 April 2010; pp. 300–303. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/5486558 (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Hansson, L.; Nerhagen, L. Regulatory measurements in policy coordinated practices: The case of promoting renewable energy and cleaner transport in Sweden. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebe, U.; Dobers, G.M. Decomposing public support for energy policy: What drives acceptance of and intentions to protest against renewable energy expansion in Germany? Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 47, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aste, N.; Buzzetti, M.; Caputo, P.; Del Pero, C. Regional policies toward energy efficiency and renewable energy sources integration: Results of a wide monitoring campaign. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 36, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, D.; Axsen, J.; Mallett, A. The role of environmental framing in socio-political acceptance of smart grid: The case of British Columbia, Canada. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 1939–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, H.; Pedersen, C.S. Low-frequency noise from large wind turbines. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2011, 129, 3727–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierpont, N. Wind Turbine Syndrome: A Report on a Natural Experiment; K-Selected Books: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 2009; p. 270. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, E.; Larsman, P. The impact of visual factors on noise annoyance among people living in the vicinity of wind turbines. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, R.; Sulsky, S.I.; Kreiger, N. Using residential proximity to wind turbines as an alternative exposure measure to investigate the association between wind turbines and human health. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2018, 143, 3278–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everaert, J.; Stienen, E.W. Impact of wind turbines on birds in Zeebrugge (Belgium). In Biodiversity and Conservation in Europe; Springer: Dordrecht, Germany, 2006; pp. 103–117. [Google Scholar]

- Aschwanden, J.; Stark, H.; Peter, D.; Steuri, T.; Schmid, B.; Liechti, F. Bird collisions at wind turbines in a mountainous area related to bird movement intensities measured by radar. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 220, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xu, G.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X. Learning deep representation of imbalanced SCADA data for fault detection of wind turbines. Measurement 2019, 139, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.T.; Santos, C.D.; Hanssen, F.; Muñoz, A.R.; Onrubia, A.; Wikelski, M.; Moreira, F.; Palmeirim, J.; Silva, J.P. Wind turbines cause functional habitat loss for migratory soaring birds. J. Anim. Ecol. 2020, 89, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limpens, G.; Jeanmart, H. Electricity storage needs for the energy transition: An EROI based analysis illustrated by the case of Belgium. Energy 2018, 152, 960–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capellán-Pérez, I.; De Castro, C.; Arto, I. Assessing vulnerabilities and limits in the transition to renewable energies: Land requirements under 100% solar energy scenarios. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 77, 760–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijts, N.M.; Molin, E.J.; Steg, L. Psychological factors influencing sustainable energy technology acceptance: A review-based comprehensive framework. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, G. Determining the local acceptance of wind energy projects in Switzerland: The importance of general attitudes and project characteristics. Energy Res & Soc Sci 2014, 4, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessette, D.L.; Arvai, J.L. Engaging attribute tradeoffs in clean energy portfolio development. Energy Policy 2018, 115, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volken, S.; Wong-Parodi, G.; Trutnevyte, E. Public awareness and perception of environmental, health and safety risks to electricity generation: An explorative interview study in Switzerland. J. Risk Res. 2019, 22, 432–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. Public acceptance of constructing coastal/inland nuclear power plants in post-Fukushima China. Energy Policy 2017, 101, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, T.A. Discourse and Communication: New Approaches to the Analysis of Mass Media Discourse and Communication; Walter de Gruyter Publishing: Berlin, Germany, 2011; Volume 10, p. 375. [Google Scholar]

- De Vreese, C.H.; Boomgaarden, H.G. Media message flows and interpersonal communication: The conditional nature of effects on public opinion. Commun. Res. 2006, 33, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Link, M.W.; Childs, J.H.; Tesfaye, C.L.; Dean, E.; Stern, M.; Pasek, J.; Cohen, J.; Callegaro, J.; Harwood, P. Social media in public opinion research: Executive summary of the aapor task force on emerging technologies in public opinion research. Public Opin. Q. 2014, 78, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truelove, H.B. Energy source perceptions and policy support: Image associations, emotional evaluations, and cognitive beliefs. Energy Policy 2012, 45, 478–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, C.; Visschers, V.; Siegrist, M. Affective imagery and acceptance of replacing nuclear power plants. Risk Anal. Int. J. 2012, 32, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, E.; Slovic, P. The role of affect and worldviews as orienting dispositions in the perception and acceptance of nuclear power 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 26, 1427–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutel, M.E.; Glaesmer, H.; Wiltink, J.; Marian, H.; Brähler, E. Life satisfaction, anxiety, depression and resilience across the life span of men. Aging Male 2010, 13, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, J.S.R.; Staten, R.T.; Hall, L.A.; Lennie, T.A. The relationship among young adult college students’ depression, anxiety, stress, demographics, life satisfaction, and coping styles. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 33, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sociologický Ústav (Akademie věd ČR). Centrum pro Výzkum Veřejného Mínění. Naše Společnost 2019 May. Version 1.0. Praha: Český Sociálněvědní Datový Archiv. 2019. Available online: http://nesstar.soc.cas.cz/webview/index.jsp?v=2&previousmode=download&includeDocumentation=on&analysismode=download&study=http%3A%2F%2F147.231.52.118%3A80%2Fobj%2FfStudy%2FV1905&format=SPSS&gs=6&ddiformat=pdf&mode=documentation&top=yes (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Stewart, G.; Kamata, A.; Miles, R.; Grandoit, E.; Mandelbaum, F.; Quinn, C.; Rabin, L. Predicting mental health help seeking orientations among diverse undergraduates: An ordinal logistic regression analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 257, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Shepherd, B.E.; Li, C.; Harrell Jr, F.E. Modeling continuous response variables using ordinal regression. Stat. Med. 2017, 36, 4316–4335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helwig, N.E. Regression with ordered predictors via ordinal smoothing splines. Front. Appl. Math. Stat. 2017, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visschers, V.H.; Siegrist, M. Find the differences and the similarities: Relating perceived benefits, perceived costs and protected values to acceptance of five energy technologies. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, K.; Ustad Figenschou, T.; Frischlich, L. Key dimensions of alternative news media. Digit. Journal. 2019, 7, 860–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seargeant, P.; Tagg, C. Social media and the future of open debate: A user-oriented approach to Facebook’s filter bubble conundrum. Discourse Context Media 2019, 27, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaakinen, M.; Sirola, A.; Savolainen, I.; Oksanen, A. Shared identity and shared information in social media: Development and validation of the identity bubble reinforcement scale. Media Psychol. 2020, 23, 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevett, J. The Greta Effect? Meet the Schoolgirl Climate Warriors. BBC News. Available online: https://www.dhushara.com/Biocrisis/19/5/climate%20warrriors.Reduce%20to%20300%20dpi%20average%20quality%20-%20STANDARD%20COMPRESSION.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2020).

- Thunberg, G.; Our House is on Fire. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/jan/25/our-house-is-on-fire-greta-thunberg16-urges-leaders-to-act-on-climate (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Qazi, A.; Hussain, F.; Rahim, N.A.; Hardaker, G.; Alghazzawi, D.; Shaban, K.; Haruna, K. Towards sustainable energy: A systematic review of renewable energy sources, technologies, and public opinions. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 63837–63851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, T.M.; Prabhakar, G.; Strakova, L. Social media information benefits, knowledge management and smart organizations. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sütterlin, B.; Siegrist, M. Public acceptance of renewable energy technologies from an abstract versus concrete perspective and the positive imagery of solar power. Energy Policy 2017, 106, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator on Opinion on RES-E | Hypothesis | Factor |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Public opinion on whether it is possible to replace traditional electricity production with RES-E (H1,i) and 2 Public evaluation of current situation concerning use of renewable energy sources in the Czech Republic (good/bad H2,i) are related to | H1,1 H2,1 | the exposure to sources of information (mass media, social networks, Internet and non-internet discussions) |

| H1,2 H2,2 | to sensitivity to environment protection | |

| H1,3 H2,3 | the worries concerning nuclear energy | |

| H1,4 H2,4 | subjective living standard | |

| H1,5 H2,5 | subjective life satisfaction |

| 1, % | 2, % | 3, % | 4, % | No Opinion, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of renewable energy resources in the Czech Republic, 1—very good, 4—very bad | 1.8 | 29.2 | 39.6 | 12.5 | 16.8 |

| It is possible to replace electricity from conventional sources with renewables, 1—yes, 4—no | 11.2 | 33.8 | 29.8 | 11.3 | 13.8 |

| How Often Do You Follow Country Level Social Life Via | at Least Once a Day, % | Several Times a Week, % | Once a Week, % | Less Than Once a Week, % | Never, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TV | 47.4 | 32.7 | 7.4 | 7.7 | 4.8 |

| Printed newspapers and magazines | 8.6 | 23.9 | 22.1 | 22.2 | 22.9 |

| Radio | 21.9 | 32.1 | 12.7 | 16.0 | 17.2 |

| News web pages on internet | 17.2 | 29.5 | 15.1 | 11.0 | 24.5 |

| Internet discussions and blogs | 6.2 | 13.7 | 13.6 | 16.2 | 49.5 |

| Social networks (for example Facebook, Twitter or Instagram) | 10.0 | 16.2 | 10.3 | 13.4 | 49.7 |

| Discussions outside of internet | 5.8 | 18.2 | 21.2 | 24.8 | 29.3 |

| Indicators of Concern for the Environment | 1, % | 2, % | 3, % | 4, % | No Opinion, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Czech Republic cares about the environment, 1—too much, 2—adequately, 3—too little | 1.9 | 48.3 | 44.9 | 4.8 | |

| Sufficiency of information about environment R, 1—sufficient information, 4—insufficient information | 2.3 | 35.7 | 45.3 | 10.2 | 6.3 |

| Saves energy and water due to environment, 1—always, 4—never | 19.2 | 42.7 | 24.5 | 12.2 | 0.8 |

| 1, % | 2, % | 3, % | 4, % | 5, % | No Opinion, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concern for the nuclear energy use | ||||||

| If worried of nuclear energy, 1—very worried 4—not at all worried | 6.9 | 25.4 | 37.9 | 24.8 | 5. 0 | |

| Life satisfaction and household living standard | ||||||

| Life satisfaction, 1—very satisfied, 5—very unsatisfied | 15.8 | 50.8 | 23.6 | 8.4 | 1.3 | 0.1 |

| Household Living Standard, 1—very good, 5—very bad | 9.4 | 45.6 | 34.0 | 9.5 | 1.3 | 0.3 |

| It is Possible to Replace Electricity from the Conventional Resources with the Renewables | Use of Renewable Energy Resources in CR | It is Possible to Replace the Electricity from the Conventional Resources, No Opinion | Situation in our Case of Renewable Energy Resources. No Opinion | Corr. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Sig. | Estimate | Sig. | Estimate | Sig. | Estimate | Sig. | ||

| Threshold = 1 | −1.882 | 0.000 | −4.328 | 0.000 | 3.023 | 0.000 | 3.275 | 0.000 | |

| Threshold = 2 | 0.330 | 0.287 | −0.714 | 0.029 | |||||

| Threshold = 3 | 2.291 | 0.000 | 1.788 | 0.000 | |||||

| Sources of information | |||||||||

| TV | 0.042 | 0.617 | 0.068 | 0.446 | 0.220 | 0.120 | 0.229 | 0.073 | 0.987*** |

| Printed newspapers and magazines | −0.046 | 0.570 | 0.123 | 0.146 | −0.084 | 0.558 | 0.107 | 0.424 | 0.989*** |

| Radio | 0.094 | 0.225 | −0.046 | 0.563 | −0.096 | 0.478 | 0.155 | 0.227 | 0.975*** |

| News web pages on Internet | −0.214* | 0.020 | 0.157 | 0.106 | 0.187 | 0.209 | −0.205 | 0.137 | 0.851*** |

| Internet discussions and blogs | 0.073 | 0.451 | −0.163 | 0.114 | 0.003 | 0.986 | −0.025 | 0.871 | 0.874*** |

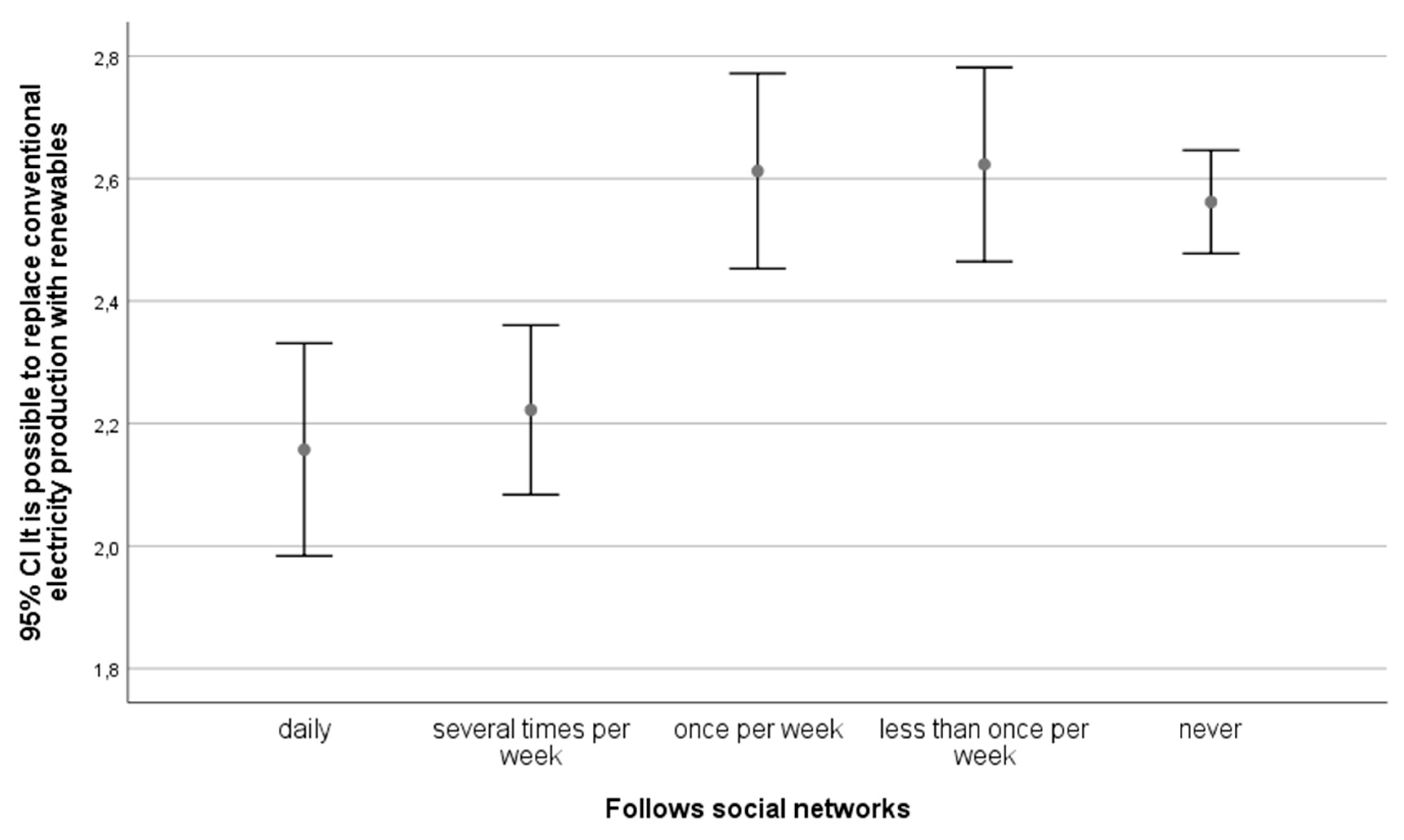

| Social networks | 0.220* | 0.020 | 0.040 | 0.688 | 0.017 | 0.922 | 0.127 | 0.415 | 0.936*** |

| Discussions outside of internet | −0.027 | 0.718 | −0.043 | 0.573 | 0.012 | 0.925 | 0.202 | 0.092 | 0.969*** |

| Environmental concerns | |||||||||

| The Czech Republic cares about the environment | −0.167* | 0.016 | 0.572*** | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.914 | −0.067 | 0.555 | 0.967*** |

| Saves energy and water due to environmental | 0.306** | 0.003 | −0.066 | 0.479 | 0.154 | 0.178 | −0.085 | 0.560 | 0.694*** |

| Self-claimed knowledge of environment | 0.224** | 0.001 | 0.101 | 0.157 | 0.702* | 0.013 | 0.409 | 0.066 | 0.648*** |

| Concerns for nuclear energy | |||||||||

| If afraid of nuclear energy | 0.377*** | 0.000 | −0.204** | 0.006 | 0.050 | 0.668 | 0.083 | 0.447 | 0.974*** |

| Socio-demographics and other | |||||||||

| Household Living Standard | 0.292** | 0.001 | −0.022 | 0.808 | −0.048 | 0.737 | −0.052 | 0.698 | 0.932** |

| Satisfaction with life | −0.048 | 0.570 | 0.164 | 0.060 | 0.210 | 0.147 | 0.246 | 0.072 | 0.966** |

| Age | 0.008 | 0.122 | 0.000 | 0.993 | 0.006 | 0.490 | 0.021* | 0.010 | |

| Political orientation | −0.011*** | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.069 | 0.002 | 0.674 | 0.002 | 0.544 | |

| Gender (men) | 0.152 | 0.276 | −0.048 | 0.741 | −0.222 | 0.353 | −0.553* | 0.015 | |

| Education elementary | 0.220 | 0.403 | −0.586* | 0.032 | 1.008* | 0.022 | 1.041** | 0.009 | |

| Education secondary w/o state exam | −0.187 | 0.338 | −0.379 | 0.066 | 0.488 | 0.219 | 0.619 | 0.073 | |

| Education secondary with state exam | −0.149 | 0.428 | −0.085 | 0.666 | 0.453 | 0.244 | 0.072 | 0.838 | |

| Cox and Snell Pseudo R-Square | 0.127 | 0.127 | 0.042 | 0.061 | |||||

| Nagelkerke Pseudo R-Square | 0.138 | 0.143 | 0.086 | 0.116 | |||||

| McFadden Pseudo R-Square | 0.054 | 0.063 | 0.064 | 0.085 | |||||

| N | 772 | 754 | 860 | 859 | |||||

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.009 | 0.000 | |||||

| Multiple Comparisons | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|

| ANOVA | 0.000 | |

| Post Hoc Tests (LSD) | ||

| daily | x times per week | 0.577 |

| once per week | 0.000 | |

| < once per week | 0.000 | |

| never | 0.000 | |

| x times per week | once per week | 0.001 |

| < once per week | 0.000 | |

| never | 0.000 | |

| once per week | less than once per week | 0.927 |

| never | 0.602 | |

| < once per week | never | 0.490 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Čábelková, I.; Strielkowski, W.; Firsova, I.; Korovushkina, M. Public Acceptance of Renewable Energy Sources: a Case Study from the Czech Republic. Energies 2020, 13, 1742. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13071742

Čábelková I, Strielkowski W, Firsova I, Korovushkina M. Public Acceptance of Renewable Energy Sources: a Case Study from the Czech Republic. Energies. 2020; 13(7):1742. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13071742

Chicago/Turabian StyleČábelková, Inna, Wadim Strielkowski, Irina Firsova, and Marina Korovushkina. 2020. "Public Acceptance of Renewable Energy Sources: a Case Study from the Czech Republic" Energies 13, no. 7: 1742. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13071742

APA StyleČábelková, I., Strielkowski, W., Firsova, I., & Korovushkina, M. (2020). Public Acceptance of Renewable Energy Sources: a Case Study from the Czech Republic. Energies, 13(7), 1742. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13071742