Research on an Enterprise Remanufacturing Strategy Based on Government Intervention

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Based on the development of China’s remanufacturing industry, a practical context has arisen, whereby manufacturers outsource part of their remanufacturing business to remanufacturers;

- (2)

- Many existing studies take the ratio between a government’s green subsidies for remanufactured products and green taxes on new products as exogenous variables. This article regards this ratio as an endogenous variable, which helps to provide the government with more practical legal policies. The analysis of the calculation examples in this study strongly proves that the government should consider the optimal ratio between government subsidies and tax policies.

2. Literature Review

3. Model Formulation

3.1. Model Framework

3.2. Notations and Descriptions

3.3. Assumption

- (1)

- Considering the wear and tear of products during the remanufacturing process, this study assumes that the remanufactured products will be scrapped after consumers have finished using them, and will no longer flow into the supply chain;

- (2)

- Waste products are derived from wasted products, so the recycling volume of wasted products is less than or equal to the output of new products in the previous period, namely ;

- (3)

- In models N, G, and GF, the remanufacturers determine their remanufacturing outsourcing proportion, denoted as , while the outsourcing business volume is . Based on the principle of the extended producer responsibility, the manufacturers are responsible for the remanufacturing of the remaining waste products, ;

- (4)

- Since waste products can be used in the production of remanufactured products, the resources required to produce remanufactured products are lower than those required to produce new products, and remanufacturers are more specialized in the remanufacturing industry, therein ;

- (5)

- Based on the fact that Chinese consumers have low acceptance of remanufactured products, we set the consumers’ acceptance of remanufactured products as ;

- (6)

- We assume that the market size is 1 and consumers’ willingness to pay for new products is , which is evenly distributed within [0, 1]. The consumers’ willingness to pay for remanufactured goods is . Therefore, the net utility available to consumers when purchasing new products is , while the net utility available to consumers when purchasing recycled products is . We view the demand function for new products as and for remanufactured products as without the government subsidy. With the government green product subsidy, the demand functions are , .

- (7)

- The reward and punishment function for the government is: . When , L represents the government recycling reward; when , L represents the recycling penalty;

- (8)

- Based on the EPR principles, government subsidies for green consumers will encourage consumers to purchase remanufactured products. In order to better fulfill the EPR principles, the government should provide green consumption subsidies to consumers who purchase remanufactured products. The government should also levy green taxes on manufacturers that produce new products. The ratio between green subsidies and green taxes is greater than 1, which is .

4. Stackelberg Game Models

4.1. Model N (Free Recycling Mode)

4.2. Model G (Government Regulation Model Based on Reward–Penalty Mechanism)

4.3. Model GF (Government Dual-Intervention Mode)

4.4. Comparison of the Three Modes

5. Numerical Analysis

5.1. Environmental Performance Perspective

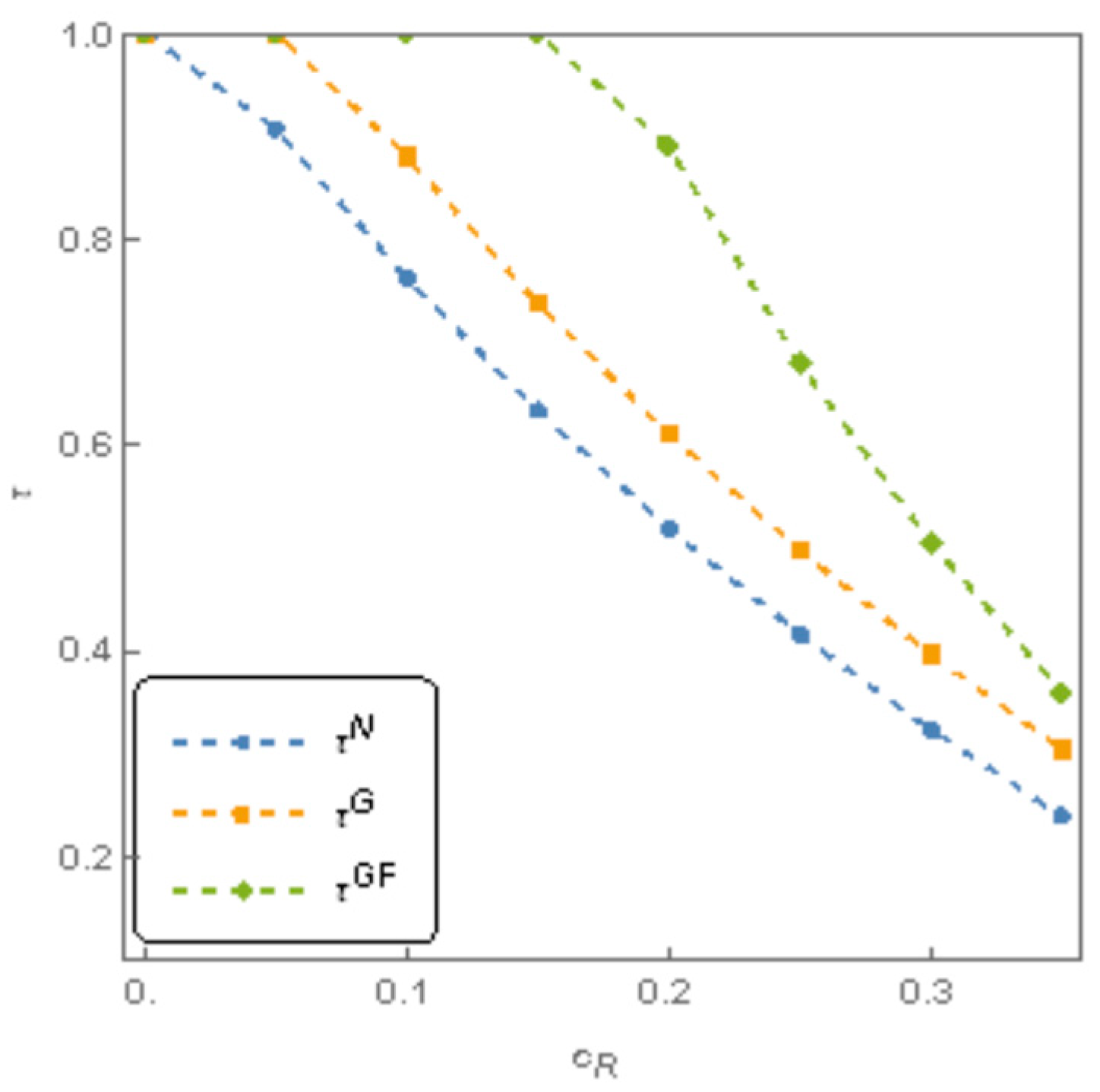

- (1)

- The recycling rates under models G and GF are greater than those under model N, indicating that government regulations can effectively guide manufacturers to improve their recycling rates and achieve greater environmental performance;

- (2)

- Comparing the remanufacturing cost ranges for 100% recycling under the three models, model GF has the longest range, model G is second, and model N has the shortest range. This shows that under model GF (the government dual-intervention mode) full recycling can easily be achieved, model N (Free Recycling mode) is the most difficult to achieve full recycling, and model G (government regulation model based on a reward–penalty mechanism) is somewhere in between. Figure 2 shows that the reward–penalty mechanism and green subsidy and tax regulations can effectively encourage manufacturers to recycle all waste products, even when the remanufacturing industry is immature. The intervention of the government is very important in the early stage of the development of the remanufacturing industry.

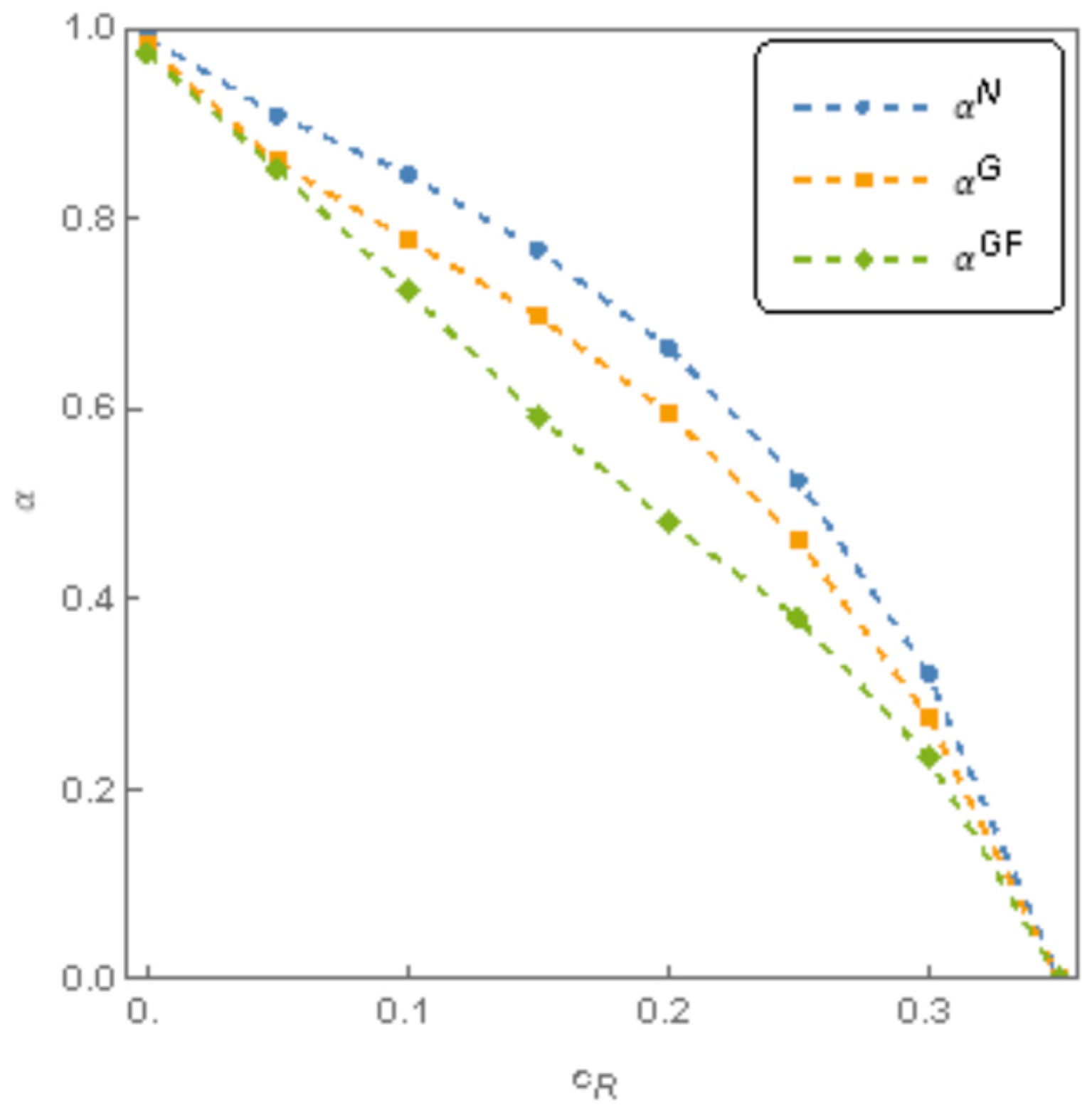

5.2. Business Cooperation Perspective

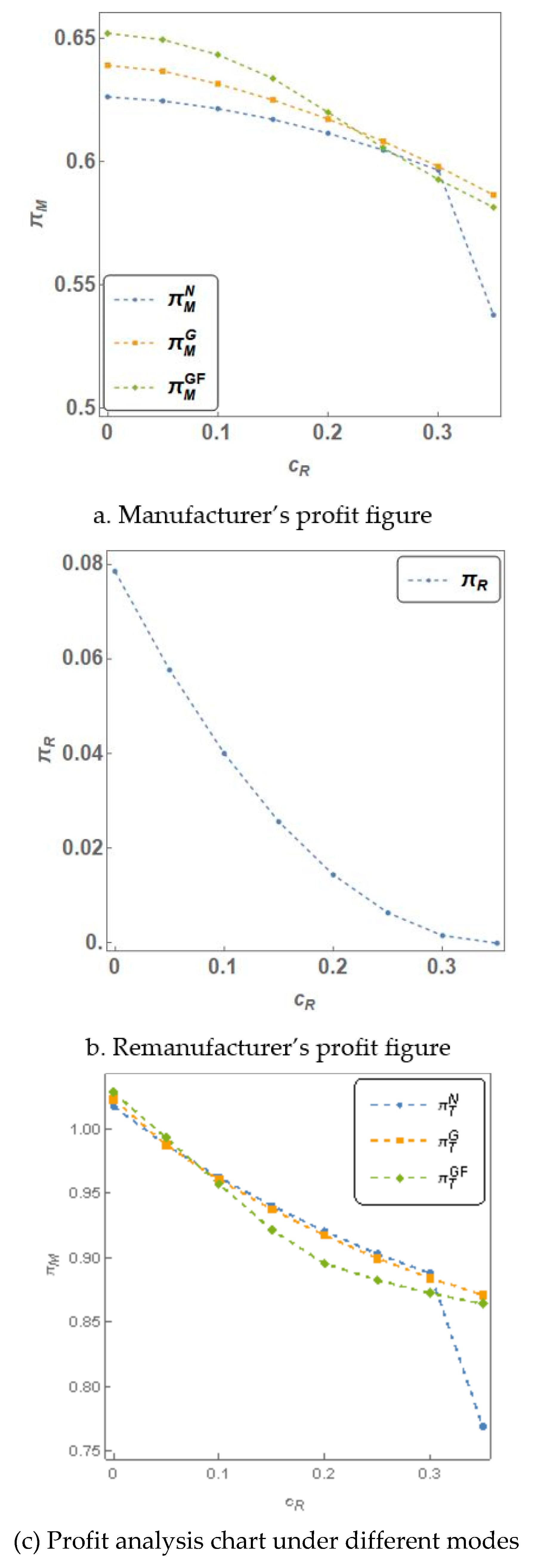

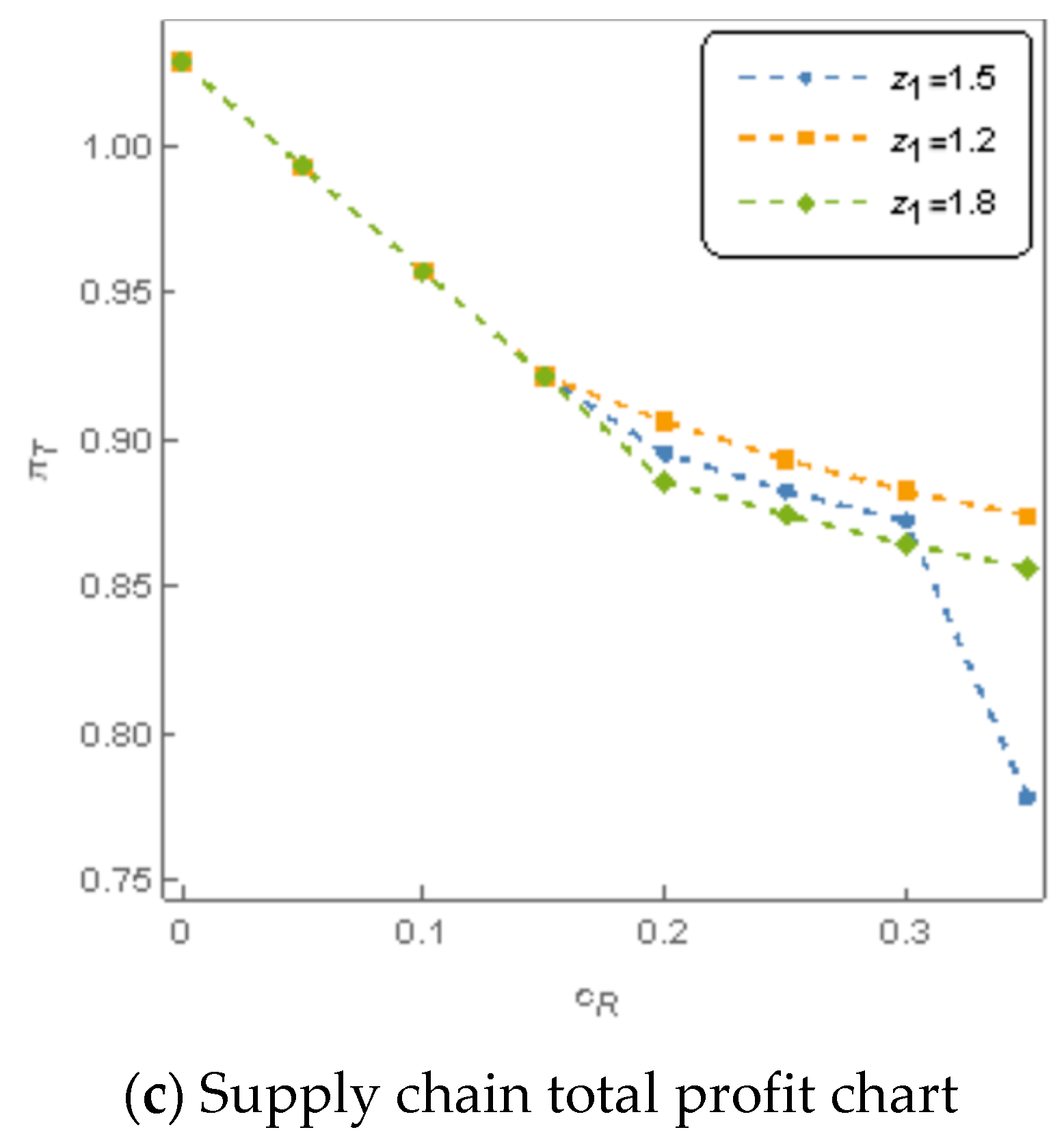

5.3. Economic Benefit Perspective

- (1)

- When the remanufacturing industry is in the early stage of development, as shown in Figure 4a,c, the manufacturers’ profits and the total supply chain profits are significantly lower than with model G or model GF. This shows that when the remanufacturing industry is in a relatively immature period, government intervention will obviously increase manufacturers’ profits and the total supply chain profits. Therefore, the government plays an important role in guiding the transformation of the remanufacturing industry from the primary stage to the mature stage;

- (2)

- Under the GF model, the manufacturers’ profits basically increase as the remanufacturing industry gradually matures; that is, the unit cost for remanufactured products produced by remanufacturers decreases. The reason for the turning point in the manufacturers’ profit curve lies in the changes in government regulations. It can be seen from the figure that the dual government regulations have a more significant impact on profits than a single government regulation. When the manufacturers do not fully recycle, the government will sacrifice its profits in order to maximize the total social welfare benefits; when the manufacturers fully recycle, the government will maintain its own profit margins;

- (3)

- When the remanufacturing industry is at the early stage of development, there is no significant difference in the manufacturers’ profits between model G and model GF, however the total supply chain profits under the model G are significantly higher than the total supply chain profits under model GF. This shows that when the remanufacturing industry is in the early stages of development, dual interventions have an obvious effect on promoting recycling among manufacturers, however this essentially occurs in exchange for some of the profits from the entire supply chain. At this time, the government scheme involving reward and punishment regulations based on the recycling rate is better and more effective in terms of maximizing social profits;

- (4)

- When the remanufacturing industry is relatively mature, the profits for manufacturers under model GF and model N are significantly lower than under model G. Under the three models, there is no significant difference in the manufacturers’ profit. This shows that when the remanufacturers are relatively mature, the government scheme involving reward and punishment regulations based on the recycling rate is better and more effective in terms of maximizing the manufacturers’ profits.

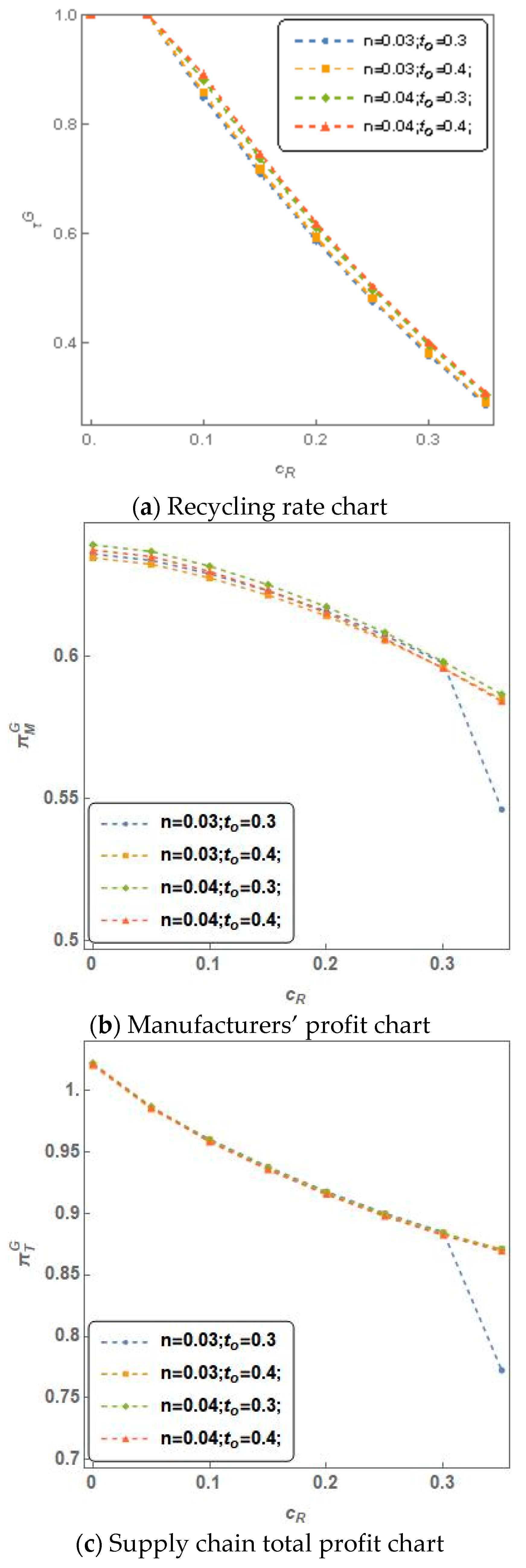

5.4. Government Strategy Perspective

6. Summary

- (1)

- When the manufacturers and the remanufacturers cooperate, the manufacturers take into account the remanufacturer is professional at producing remanufacturered products. Based on the status of China’s remanufacturing industry, this research assumes that manufacturers collect waste products via self-built channels. For the sake of cost optimization and to reduce competition, manufacturers outsource some of the remanufacturing business to remanufacturers. At this time, the government’s reward–penalty mechanism based on the recycling rate has a positive effect on manufacturers’ recycling activities. Increasing the basic recycling rate setting or improving the intensity of the reward–penalty mechanism can increase the recycling rate. When the remanufacturing industry is in the early stages of development, increasing the intensity can effectively increase the manufacturers’ profits and the total supply chain profits. It is worth noting that when manufacturers and remanufacturers cooperate, most of the profits go to the manufacturers, while remanufacturers make stable but meagre profits and the manufacturers occupy a dominant market position. The remanufacturers can try to create revenue sharing contracts with the manufacturers;

- (2)

- The government dual-regulation approach can encourage manufacturers to increase their recycling rate and enter the state of full recycling. To a certain extent, the dual regulations can motivate manufacturers to increase their recycling rate and increase their output of remanufactured products. However, essentially some of the manufacturers’ profits and the entire supply chain profits are sacrificed, meaning this is not a good long-term strategy for promoting the development of the remanufacturing industry;

- (3)

- The government dual-regulation approach can better encourage manufacturers to increase their recycling rates compared with the single reward–penalty mechanism. When manufacturers enter the state of complete recycling, the dual-regulation model can to a certain extent encourage manufacturers to increase the amount of recycling of waste products and increase the output of their own remanufactured products;

- (4)

- Government regulations are more important when the remanufacturing industry is at the beginning of its development. When the remanufacturing industry reaches a mature stage, manufacturers can voluntarily achieve a higher recovery rate in order to maximize their own profits. Therefore, the government should flexibly formulate corresponding regulatory measures according to the development of the remanufacturing industry;

- (5)

- In the state of incomplete recycling by manufacturers, the government increases the ratio between green consumption subsidies and green taxes on new products, helping to increase manufacturers’ recycling rates and the cost range for complete recycling; more importantly, this approach does not necessarily harm the manufacturers’ profits and the total supply chain profits. This shows that the government should figure out the optimal ratio between government subsidies and tax policies.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Solution Process for Model N

Appendix B. Solution Process for Model GF

References

- Mian, M.; Zeng, X.; Nasry, A.N.B.; Al-Hamadani, S.M.Z.F. Municipal solid waste management in China: A comparative analysis. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2017, 19, 1127–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoornweg, D.; Bhada-Tata, P. What a Waste: A Global Review of Solid Waste Management; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, M.K.; Goldizen, B.F.C.; Sly, P.D.; Brune, M.M.-N.; Neira, M.; Berg, M.V.D.; Norman, E.R. Health consequences of exposure to e-waste: A systematic review. Lancet Glob. Health 2013, 1, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihedioha, J.N.; Ukoha, P.O.; Ekere, N.R. Ecological and human health risk assessment of heavy metal contamination in soil of a municipal solid waste dump in Uyo, Nigeria. Environ. Geochem. Health 2017, 39, 497–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Kaliyan, M.; Kannan, D.; Haq, A. Barriers analysis for green supply chain management implementation in Indian industries using analytic hierarchy process. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 147, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Huang, T. An optimization model for green supply chain management by using a big data analytic approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 1085–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Soleimani, H.; Kannan, D. Reverse logistics and closed-loop supply chain: A comprehensive review to explore the future. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 240, 603–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindhqvist, T. Extended Producer Responsibility in Cleaner Production: Policy Principle to Promote Environmental Improvements of Product Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- End of Life Vehicles—Waste—Environment—European Commission. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/waste/elv/index.htm (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- Waste Electronic Equipment—Environment—European Commission. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/waste/weee/index_en.htm (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- Development of Guidance On Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR)—Waste—Environment—European Commission. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/archives/waste/eu_guidance/introduction.html (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- Nash, J.; Bosso, C. Extended producer responsibility in the United States: Full speed ahead? J. Ind. Ecol. 2013, 17, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- METI Ministry Of Economy, Trade And Industry. 2020. Available online: https://www.meti.go.jp/policy/recycle/main/english/law/contain.html (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- Hoornweg, D.; Lam, P.; Chaudhry, M. Waste Management in China: Issues and Recommendations. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Waste-management-in-China-%3A-issues-and-Hoornweg-Lam/9fc9a4e94e6dcebe1d028f6119a56305fd1407c2 (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- Notice on Carrying out Energy-Saving Products Benefiting People Project (Caijian [2009] No. 213)-National Development and Reform Commission. 2020. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/fggz/hjyzy/jnhnx/200905/t20090525_1134226.html (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- Beijing Municipal Bureau of Commerce. 2020. Available online: http://sw.beijing.gov.cn/zwxx/zcfg/zcxcjd/202001/t20200109_1570593.html (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- Notice of the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development and Other Departments on the Comprehensive Implementation of Domestic Waste Classification in Cities at the Prefecture Level and Above. 2020. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-06/11/content_5399088.htm (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- Tate, W.L.; Ellram, L.M.; Kirchoff, J.F. Corporate social responsibility reports: A thematic analysis related to supply chain management. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2010, 46, 19–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollos, D.; Blome, C.; Foerstl, K. Does sustainable supplier co-operation affect performance? Examining implications for the triple bottom line. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2012, 50, 2968–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laari, S.; Töyli, J.; Ojala, L. Supply chain perspective on competitive strategies and green supply chain management strategies. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 1303–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, K.W.; Zelbst, P.J.; Meacham, J.; Bhadauria, V.S. Green supply chain management practices: Impact on performance. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehrich, J.K.; Hoejmose, S.U.; Overland, V. Driving green supply chain management performance through supplier selection and value internalisation: A self-determination theory perspective. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2017, 37, 489–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazancoglu, Y.; Kazancoglu, I.; Sagnak, M. A new holistic conceptual framework for green supply chain management performance assessment based on circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 195, 1282–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Jabbour, A.B.L.D.S. Green Human Resource Management and Green Supply Chain Management: Linking two emerging agendas. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1824–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, A.A.; Jaaron, A.A.; Bon, A.T. The impact of green human resource management and green supply chain management practices on sustainable performance: An empirical study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, S.; Garg, D.; Haleem, A. The impacts of critical success factors for implementing green supply chain management towards sustainability: An empirical investigation of Indian automobile industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 121, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.R.; Qianli, D. Impact of green supply chain management practices on firms’ performance: An empirical study from the perspective of Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 16829–16844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryanto, T.; Haseeb, M.; Hartani, N.H. The correlates of developing green supply chain management practices: Firms level analysis in Malaysia. Int. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2018, 7, 316. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Zhu, M.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Z. Pricing policies of a competitive dual-channel green supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 2029–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Zhou, Y. Manufacturer-remanufacturing vs supplier-remanufacturing in a closed-loop supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 176, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, J.; Govindan, K.; Sadeghi, R. Reverse supply chain coordination under stochastic remanufacturing capacity. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 202, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, Y. Recycling mechanisms and policy suggestions for spent electric vehicles’ power battery—A case of Beijing. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 186, 388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fan, L.; Ma, P.; Zhang, P.; Lu, Z. Reward-penalty mechanism in a closed-loop supply chain with sequential manufacturers’ price competition. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhao, X.; Cheng, M. Closed-loop supply chains under reward-penalty mechanism: Retailer collection and asymmetric information. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 3938–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, J.-B.; Chen, Y.J. Impact of government financial intervention on competition among green supply chains. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 138, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Hu, Q.; Lou, Y.T.; Zhou, G.G. Remanufacturing Supply Chain Decision-making Mechanism Based on Governments Environmental Regulation. China Mech. Eng. 2012, 23, 2694–2702. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.-M.; Zhao, Z.; Ke, H. Dual-channel closed-loop supply chain with government consumption-subsidy. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2013, 226, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Han, X.; Hu, G. Optimal production for manufacturers considering consumer environmental awareness and green subsidies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 182, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigerna, S.; Wen, X.; Hagspiel, V.; Kort, P.M. Green electricity investments: Environmental target and the optimal subsidy. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 279, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tong, Y.; Ye, F.; Song, J. The choice of the government green subsidy scheme: Innovation subsidy vs. product subsidy. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 4932–4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cao, J.; Kumar, S. Government regulation and enterprise decision in China remanufacturing industry: Evidence from evolutionary game theory. Energy Ecol. Environ. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, G. Considering the remanufacturing game of patent licensing and government regulation. J. Manag. Sci. 2020, 23, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.; Wu, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, G. Enterprise remanufacturing decision based on EPR system. Control Decis. 2020, 35, 1703–1716. [Google Scholar]

| Notations | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| i | i = N, G, and GF respectively represent three models, namely model N (free recycling mode), model G (government regulation model based on reward–penalty mechanism), model GF (government dual-intervention mode). |

| ,, | : the cost for the manufacturers to produce new products; : the cost for the manufacturers to produce remanufactured products; : the cost for the remanufacturers to produce remanufactured products |

| w | as unit outsourcing cost |

| public acceptance of remanufactured products, | |

| benchmark recycling rate set by the government | |

| reward–penalty intensity established by the government | |

| z | ratio between unit subsidy for green consumers and tax on new products, z = s/f |

| manufacturers’ recycling effort level, where is the cost of recycling, is the coefficient between the recycling effort and the recycling cost. , i.e., the quantities of used products recycled by manufacturers, as well as the quantities of remanufactured products; is the coefficient between the manufacturers’ recycling effort and recycling amount. | |

| actual recycling rate, i.e., , | |

| the ratio of outsourcing, ; is the quantity of remanufactured products produced by the remanufacturers; are investment costs for the technology, equipment, etc.; is the coefficient between quantities of used products and costs; are investment costs for technology, equipment, etc.; d is the coefficient between quantities of used products and costs | |

| , | new unit, remanufactured product price |

| , , | : quantities of new products produced by manufacturer; : quantities of remanufactured products produced by manufacturer; : manufacturers’ total output, |

| Remanufacturers’ output | |

| f | Government tax on new products |

| s | Government subsidies for green consumers to purchase remanufactured products; respectively represent the ratio between the unit subsidies for green consumers and the government taxes on new products when the manufacturers partially or fully recycle the wasted products |

| , , | the objective functions of the manufacturers, remanufacturers, and government |

| (N-1) | (N-2) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

| Interval | N-1 | N-2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters/Variables | ||||||

| + | − | − | − | − | − | |

| − | + | − | + | + | − | |

| − | + | + | − | − | − | |

| / | / | − | / | / | − | |

| + | − | + | − | − | + | |

| − | − | + | − | − | − | |

| + | − | − | / | / | / | |

| (G-1) | (G-2) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

| Interval | G-1 | G-2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters/Variables | ||||||||||

| + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | |

| − | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | |

| − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | |

| / | / | − | / | / | / | / | − | / | / | |

| + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | |

| − | − | + | ± | − | − | − | ± | + | − | |

| + | − | − | + | + | / | / | / | / | / | |

| Interval | GF-1 | GF-2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters/Variables | ||||||||||

| + | − | − | − | − | / | / | / | + | − | |

| (GF-1) | (GF-2) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

| Interval | GF-I | GF-II | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters/Variables | ||||||||||

| + | − | − | ± | − | − | − | − | / | / | |

| − | + | ± | ± | + | + | + | ± | / | / | |

| ± | + | + | ± | ± | − | − | − | / | / | |

| / | / | − | / | / | / | / | − | / | / | |

| + | − | ± | ± | − | − | − | + | / | / | |

| ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | − | − | ± | / | / | |

| ± | − | − | ± | ± | / | / | / | / | / | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cao, J.; Zeng, J.; Yan, Y.; Chen, X. Research on an Enterprise Remanufacturing Strategy Based on Government Intervention. Energies 2020, 13, 6549. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13246549

Cao J, Zeng J, Yan Y, Chen X. Research on an Enterprise Remanufacturing Strategy Based on Government Intervention. Energies. 2020; 13(24):6549. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13246549

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Jian, Jiayun Zeng, Yuting Yan, and Xihui Chen. 2020. "Research on an Enterprise Remanufacturing Strategy Based on Government Intervention" Energies 13, no. 24: 6549. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13246549

APA StyleCao, J., Zeng, J., Yan, Y., & Chen, X. (2020). Research on an Enterprise Remanufacturing Strategy Based on Government Intervention. Energies, 13(24), 6549. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13246549