Abstract

To facilitate energy transition, regulators have devised ‘regulatory sandboxes’ to create a participatory experimentation environment for exploring revision of energy law in several countries. These sandboxes allow for a two-way regulatory dialogue between an experimenter and an approachable regulator to innovate regulation and enable new socio-technical arrangements. However, these experiments do not take place in a vacuum but need to be formulated and implemented in a multi-actor, polycentric decision-making system through collaboration with the regulator but also energy sector incumbents, such as the distribution system operator. Therefore, we are exploring new roles and power division changes in the energy sector as a result of such a regulatory sandbox. We researched the Dutch executive order ‘experiments decentralized, sustainable electricity production’ (EDSEP) that invites homeowners’ associations and energy cooperatives to propose projects that are prohibited by extant regulation. Local experimenters can, for instance, organise peer-to-peer supply and determine their own tariffs for energy transport in order to localize, democratize, and decentralize energy provision. Theoretically, we rely on Ostrom’s concept of polycentricity to study the dynamics between actors that are involved in and engaging with the participatory experiments. Empirically, we examine four approved EDSEP experiments through interviews and document analysis. Our conclusions focus on the potential and limitations of bottom-up, participatory innovation in a polycentric system. The most important lessons are that a more holistic approach to experimentation, inter-actor alignment, providing more incentives, and expert and financial support would benefit bottom-up participatory innovation.

1. Introduction

Perhaps one of the most critical issues for the energy transition is matching sustainable energy supply and demand, and especially managing the local peak loads and the influx of prosumer energy since many renewables are intermittent resources. For now, the existing grid is used for balancing, but when renewable electricity production and use further increase, the grid capacity will not be sufficient and reinforcement will be very expensive. New options for grid management that have been explored are smart meters, smart grids, demand response, and storage technologies to reduce peak loads and manage congestion. These technological developments create opportunities for new roles in the energy system, such as aggregators [1,2,3].

New technological developments are also relevant from a prosumer perspective [4,5]. Until recently, project partners in smart grid projects perceived users primarily as a barrier [6], or as passive subscribers to grid services [7]. Planko et al. show that end-users are scarcely represented in the system-building networks that are active in the development of the Dutch smart grid sector [8]. Yet, times are changing with the increase of local energy initiatives [9], which increasingly broaden their activities that aim to further influence the direction and pace of the energy transition [10]. Potentially, local energy initiatives can extend their role from energy generation to performing active functions within the smart grid. They could ‘actively offer services that electric utilities, transmission service operators or other prosumers have to bid for’ [11] (p.4), such as offering storage capacity for balancing, or avoiding grid reinforcement through flattening the usage profile and increasing real-time use and local storage [12].

Local energy initiatives or other local actors would need to be enabled to organise a more integrated resource management at the local or regional level to extend and optimise such services. For instance, peer-to-peer supply and flexible tariffs could increase local use.

However, the extant law is sometimes a limiting factor for energy management innovation towards a renewable energy (RE)-based system that needs matching demand and supply both in terms of available energy and grid capacity [3]. For instance, for household consumers, law might need to enable pricing of grid services based on actual loads instead of connection capacity.

Several countries’ regulators have devised ‘regulatory sandboxes’ to create a participatory experimentation environment for exploring revision of energy law to overcome such legal obstacles for energy transition. A main characteristic of these sandboxes is that they allow for a two-way regulatory dialogue between an experimenter and a regulator to innovate regulation and enable new socio-technical arrangements. For instance, in the Netherlands, the executive order ‘experiments decentralized, sustainable electricity production’ (EDSEP) allows for the implementation of innovative energy services at the local level [13,14]. Another example is the UK, where innovators can get a temporary derogation of some rules in order to run a trial if the proposed product or service is considered to be genuinely innovative and able to deliver consumer benefits [15]. Importantly, new actors, such as local energy initiatives, take centre stage in these sandbox experiments, and they are seen as a locus of agency, in contrast with ‘business as usual’ in smart grid experiments, as described above [6,7,8].

What is especially interesting about these experiments is that, while experimenters can take on new roles due to exemptions, they do not operate in a vacuum, but experiments need to be designed and implemented in a multi-actor, multi-centered decision-making system. Such a system was coined by V. Ostrom et al. as a polycentric system [16] and was further elaborated by E. Ostrom [17,18]. In the particular polycentric system in this study, the experimenters need to collaborate with the regulator, but also energy sector incumbents, such as the distribution system operator.

Little is known regarding the functioning and innovative potential of local energy initiatives as experimenters in polycentric actor-constellations [19], while they are earmarked as potential providers of new grid services in such a system by governments creating these experimentation environments [11]. Our central question, therefore, is: What can be learnt about local energy initiatives’ bottom-up experimentation with smart grids in a polycentric energy system? By answering this question, we aim to provide policy relevant insights regarding the preconditions for and obstacles to using end-user collectives as innovators informing new energy regulation, which is more facilitative of the integration of renewables within the limits of the grid. Furthermore, we would like to introduce the polycentricity concept to the community energy literature and demonstrate its value to better understand the relationality and interdependencies in governing energy.

To research this, we focus on the aforementioned case of the Dutch EDSEP, which invites homeowners’ associations and energy cooperatives to propose projects that are prohibited by extant energy regulation. Local experimenters can, for instance, organize peer-to-peer supply and determine their own tariffs for energy transport in order to localize, democratize, and decentralize sustainable energy provision. We further introduce our case in Section 2. Subsequently, we elaborate on our theoretical framework, in particular the concept polycentricity, in Section 3. In Section 4, we describe the used case study methodology and introduce the four EDSEP projects that are analyzed in-depth. Afterwards, we will describe the polycentric configuration under the EDSEP, and the functioning of the experimenters in this configuration in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 concludes the article with a discussion of our findings in a broader context and the value of the polycentricity literature for studying the potential and limitations of bottom-up, participatory innovation in a polycentric system.

2. Policy Background and Introduction EDSEP

In this section, we introduce the policy developments that led to the EDSEP, and the EDSEP itself.

2.1. Policy Background

The direct reason for the EDSEP is the 2013 Social and Economic Council (SER) energy agreement for sustainable growth between over 40 Dutch organizations and supported by the Dutch national government [13]. In the text of the energy agreement, it is stated that: “To realize the energy transition the legislation needs to be providing a consistent framework to provide investors with long-term security. In addition, the legislation needs to facilitate innovation. This means that the legislation needs to provide sufficient space to enable desired new developments, specifically when it comes to the production of RE. To this end, the Gas and Electricity Acts will be revised” [20]. For the revision, the Dutch government had established the legislative agenda STROOM (abbreviation of streamlining, optimizing and modernizing, in Dutch: STROomlijnen, Optimaliseren en Moderniseren), which had achieving clearer and simpler rules to reduce bureaucracy, streamlining with European legislation, and being facilitative of a competitive economy and transition towards as sustainable energy system as its goal. This legislative proposal offered a merger of the Electricity Act 1998 and the Gas Act [21].

However, instead of waiting for the new Gas and Electricity Act, the parties in favor of local, sustainable energy lobbied to make use of article 7a sub 1 of the Electricity Act 1998. This article states that, through executive order, in accordance with European Union legislation, the Electricity Act can be derogated from by the experiment [22]. The article intends to enable relatively small-scale, localised, RE experiments for which the strictly regulated separation between the commercial activities production and supply, and the publicly managed distribution side of the energy system can be relaxed, to a certain extent under specified conditions for a particular target group of homeowners associations (HOAs) and cooperatives.

Such derogation has to be laid down in an executive order (in Dutch: Algemene Maatregel van Bestuur) and it has taken the shape as the EDSEP, which entered into force on the 28th of February 2015. The objective of the EDSEP is stated in its explanatory memorandum and it is to observe whether it is necessary to strictly apply the rules of the current Electricity Act for decentrally produced renewable electricity.

2.2. Executive Order ‘Decentral, Sustainable Electricity Production Experiments’

To informedly revise the Electricity Act, the Dutch government strives to obtain more knowledge regarding grid stabilization by prosumers and obstacles that are created by present regulations. For this reason, the Executive order ‘Decentral, sustainable electricity production experiments’(in Dutch: Besluit experimenten decentrale duurzame elektriciteitsopwekking) was designed [23]. The goals of the executive order are stimulation of more renewable energy (RE) at the local level, more efficient use of the existing energy infrastructure, and more involvement of energy consumers with their own energy supply.

It provides energy cooperatives or HOAs the opportunity to get an exemption from the Electricity Act and carry out the functions of the grid operator. The cooperatives and HOAs can carry out two main types of experiments:

- -

- the project grids up to 500 users. In this case, the grid is owned by the project and has only one connection to the public grid;

- -

- the larger experiments up to 10,000 users and 5 MW generative capacity, usually in cooperation with the grid operator. The grid operator remains owner of the grid. These experiments are concerned with balancing the electricity grid through peak shaving, and dynamic electricity tariffs.

The size of the experiments is chosen, so that the projects remain manageable and the general security and safety of the electricity provision on the regional grid will be guaranteed. Safeguarding provision within the projects is the responsibility of the participants of the projects. Thus, the protection of the consumer is partly taken care of through the assumed control that the participant can exert in the cooperative or HOA. The members should hold each other accountable for the responsibilities of the local energy initiative regarding production, supply, and transport.

Initiatives that are willing to make use of the EDSEP need to apply at the Netherlands Enterprising Agency (in Dutch: Rijksdienst voor ondernemend Nederland, RVO) for the derogation of the Electricity Act. Yearly, 10 projects of both types could be admitted, but only a total of 18 projects have been approved (see Appendix A), and only few are actually being implemented. The admission started in 2015 and ended in 2018. The experiments will be evaluated in early 2020.

3. EDSEP Experimenters As Decision-Making Unit in a Polycentric System

The EDSEP is designed to identify the obstacles that the extant Electricity Act presents to the development of local collective solutions to the production of more RE and its more efficient use. When experiments receive derogation under the EDSEP, this means that they become part of a system with decision-making units at several levels, with whom they have to cooperate, or by whom they are supervised or even opposed. These include, amongst others, grid operators, energy companies, the Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets (ACM), the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate and its executive organization RVO.

A polycentric approach is suitable for analysing the functioning of these experiments as part of such a larger system in which decision-making power is distributed [24], and it has been used for previous work on smart grids [25,26]. Polycentricity means that there are “many centres of decision-making which are formally independent of each other” [16], but which in practice often need to collaborate with others to execute what they are formally allowed to do. For instance, in the case of the EDSEP experiments, experimenters pursuing a project grid only formally need to discuss their plans regarding grid design and distribution with the regional distribution system operator (DSO), as they are allowed to take the role of DSO in their mini-grid, but in practice the approval of the regional DSO is important for obtaining the exemption.

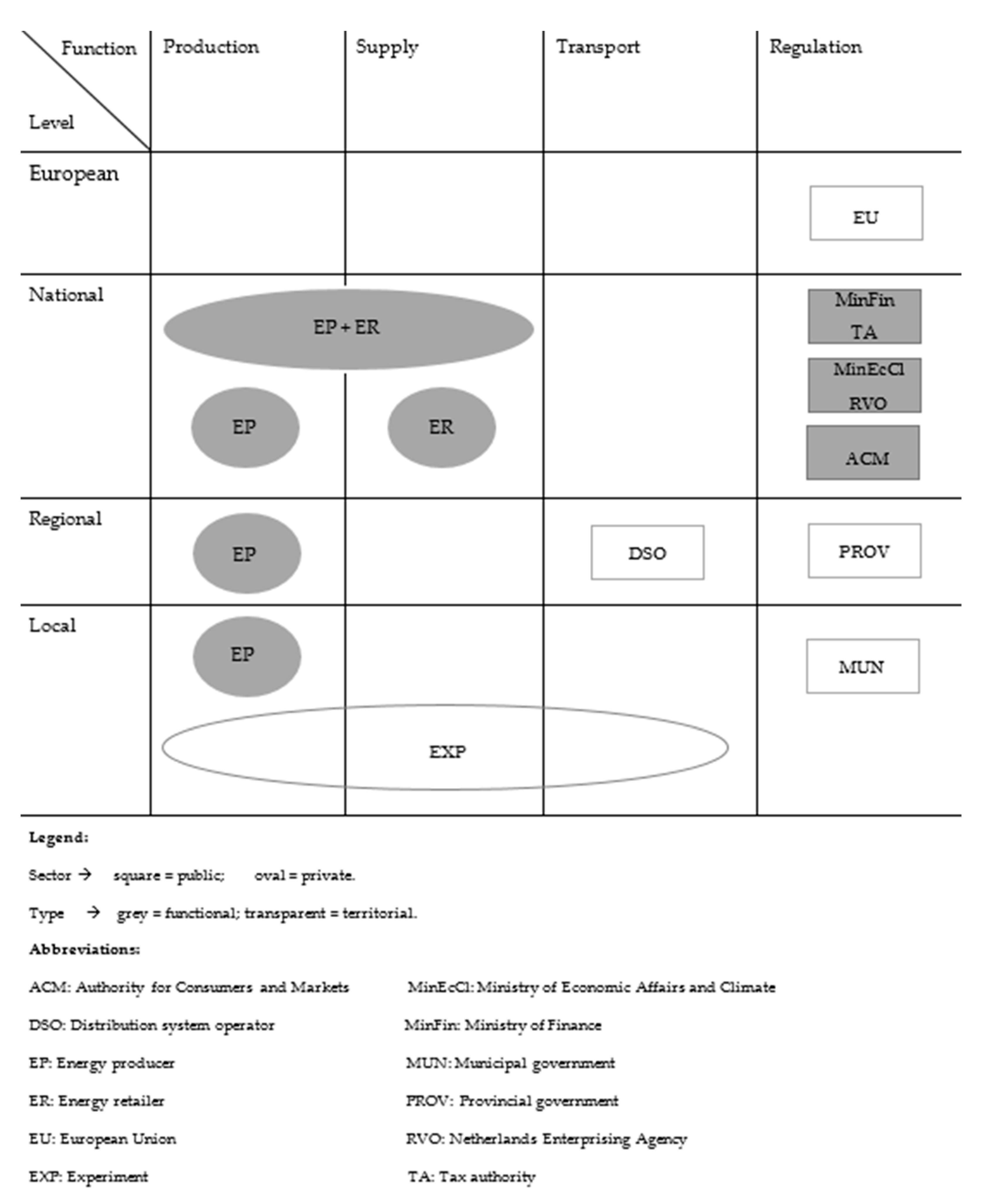

Polycentric systems are characterised in the literature as being multi-level, multi-sectoral, multi-functional, and multi-type, as displayed in Table 1 [26,27]. We will use these concepts to describe the polycentric setting in which the experiments operate in Section 4.1, as the authority of a decision-making centre in energy regulations is defined by these characteristics. For instance, a locally functioning energy initiative is a private sector initiative and has therefore previously been excluded from the function grid management, as it was deemed a public good.

Table 1.

Aspects of polycentric constellations based on [26,27].

We rely on Ostrom et al. [16] for the analysis of the polycentric system, who propose four criteria to evaluate the well-functioning of a polycentric system: control, political representation, efficiency, and local autonomy. We briefly define these criteria in Table 2.

Table 2.

Criteria for evaluating the functioning of polycentric decision-making systems [16].

4. Methods

4.1. Case Study

We study the EDSEP as a multiple case study. Case study research allows for in depth analysis of a contemporary phenomenon in a real-life context and the combination of various complementary research methods [28]. Our sample of cases includes four projects that were approved under the EDSEP: Schoonschip, Endona, Collegepark Zwijsen, and Aardehuizen. All of these started relatively early (in 2015 or 2016) and their projects have reached an advanced stage. Two of these are so-called large experiments and two are project nets, so both types of experiments that are possible within the EDSEP are equally well represented.

Many (web-)documents that describe the four cases are available, and for each case the project initiators or other participants heavily involved in the development have been interviewed in a semi-structured face-to-face interview. Although these representatives provided us with key information for this research, we acknowledge that other participants to the experiments could have different perspectives. Furthermore, we conducted interviews with other relevant actors in the polycentric system related to the EDSEP, mostly telephonic. Appendix B presents an overview of the interviewees.

This information has been analysed through reflexive thematic analysis, starting with the criteria indicating the functioning of polycentric systems as analytical framework. The coding has been based on the six-step methodology of Braun et al. [29], which consists of the steps: familiarisation, generating codes, constructing themes, revising themes, defining themes, and writing the report. We used the qualitative data analysis software Atlas.ti for our analysis.

4.2. Cases

Via Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6, we will shortly introduce all four of our case studies based on their project type, delineation of the experiment, its organization and governance, its energy system, and the use of the EDSEP.

Table 3.

Case study description Endona.

Table 4.

Case study description Aardehuizen.

Table 5.

Case study description Collegepark Zwijsen.

Table 6.

Case study description Schoonschip.

5. Results

In this section, we first discuss the polycentric constellation of actors that EDSEP experimenters need to function in, and thereafter we analyse the well-functioning of the experiments in this context.

5.1. The Polycentric Constellation of Actors Under the EDSEP

In this section, we will introduce the polycentric energy system that EDSEP experimenters are part of and function within (see Figure 1 for an overview). The selection of the actors that we discuss here is limited to actors that are directly involved in EDSEP experiments, and therefore does not include actors, such as the high voltage system operator.

Figure 1.

Overview of polycentric energy system under the EDSEP.

• Energy supplier

Dutch energy companies are traditionally large, nationally operating, private companies. In recent years, some cooperative energy companies have been founded that are closely related to local energy initiatives and seek to return at least part of the benefits to the region.

The functional energy companies receive surplus electricity from the projects and deliver electricity when the projects do not meet demand with their own production. They take care of the administration and billing for the electricity produced and consumed.

Energy suppliers that supply to small scale users, such as households, need a supply permit. This permit is given by ACM when the supplier can show amongst others that supply will be reliable, tariffs are reasonable, and the company is financially, organisationally and technically compliant with the conditions of the Electricity Act. Under these conditions, it is not feasible for local energy initiatives to act as the supplier. However, a few cooperative energy suppliers exist that supply energy that is produced by a growing number of local energy initiatives. These suppliers are cooperatives of cooperatives, of which local energy initiatives producing energy are member.

Furthermore, an energy supplier needs to have balance responsibility (in Dutch: programmaverantwoordelijkheid) or have a contract with a balance responsible party (BRP). The BRPs share the responsibility of balancing and they have to inform grid operators about their planned injections, offtakes, and transports. At the moment, experimenters are not able to take up balance responsibility and they rely on the larger national energy companies to provide this function for them.

• DSO

The DSOs in the Netherlands are territorially organized, monopolist utility companies that operate regionally. They are specialised in the transport of electricity and the maintenance and extension of the grid.

As utility companies, they are subject to forms of public control and regulation. The Authority for Consumers and Markets yearly determines the tariffs that the DSOs can charge to their clients to connect them, be connected and transport energy, and how much profit they can make on their investments.

In the large projects, the DSO remains the owner and manager of the grid, but, in the project grids, the grid is part of the project, and is built and maintained by the experimenters. The DSOs are asked by RVO to give a reaction on the project grids, and they try to be involved in the design of these grids. They want to be formally involved in the process towards the derogation.

The DSOs have considerable experience and they are well equipped to build and maintain grids. However, as the regulatory focus in the Netherlands is primarily on the public values of affordability and availability of supply, the safeguarding of sustainability is prioritized at a much lower level [4,32]. While DSOs can benefit from the sustainability experiments, they are concerned about the knowledge that is present among the experimenters to perform DSO tasks. After the 10-year-derogation, the project grid has to be potentially handed over to the DSOs, and they wonder whether the quality of these grids will be sufficient, and who must pay the costs if this is not the case.

• ACM

The ACM is a nationally and functionally operating, independent public organization. It is a business regulation agency, which is charged with competition oversight, sector-specific regulation for several sectors, and enforcement of consumer protection laws. In the context of the EDSEP, the ACM checks the calculation method for the energy and transport tariffs if the energy experiment wants to take over the task of the supplier and the DSO.

• Tax authority

The tax authority is a nationally and functionally operating public organization. It is tasked with the tax collection and customs service of the Dutch government and it is part of the Ministry of Finance. It levies and collects the energy tax on electricity (in Dutch: Energiebelasting elektriciteit). This is a type of environmental tax that disincentivizes use. The energy tax per kWh for 0–10,000 kWh electricity was in 2019 € 0.09863 [33]. This is a large share of the average electricity price in the first quarter of 2019 of € 0.203 per kWh for households using 2.5–5 MWh [34]. In the experiments, it is dependent on the circumstances within each project whether energy tax needs to be paid, and no special conditions exist.

Another tax that needs to be paid is for the storage of renewable energy (in Dutch: Opslag duurzame energie), which is € 0.0189 per kWh until 10,000 kWh [33]. In addition, a payment of 21% VAT is charged over supply costs, transport costs, and levies.

• RVO

RVO is an executive organization of the ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate, which operates nationally in the public domain with a functional agenda targeted at executing policies that support Dutch enterprising. RVO provides the derogation to the projects and supervises its implementation.

Once or twice a year it organizes meet-ups for the experiments, together with the national platform organisation for community energy, Hieropgewekt. Here, projects can create a community of practice and share learning experiences.

The types of experiments under the EDSEP are left rather open to see what kind legal changes are required to facilitate energy transition. This meant that some of the problems that the projects encountered were not foreseen, e.g., whether energy tax needed to be paid was first also not clear to RVO.

• Experimenting HOA or cooperative

The experimenters are locally operating, territorial decision-making units. The HOA’s and cooperatives themselves are voluntary bodies, but a hybrid sometimes develops where a private party is the main developer and is either founding the HOA or cooperative, or paid by it to take on an important role in the design of the experiment. The functions that an experiment can fulfil under the EDSEP in the energy system can be any type of activity in the domain of energy production, supply, or grid management for projects grids, whereas large experiments are more constrained (see Section 2.2).

• Municipality, provincial government, and European Union

The governmental bodies are, similarly to the previously described departments of the national government, public, territorial bodies, which operate at their respective scales. In the context of the EDSEP, these governments have played various roles in the polycentric energy system, such as subsidizer and provider of permits. This will be discussed in more detail in Section 5.2.4 regarding political representation.

5.2. The Functioning of the Experiments in Their Polycentric Environment

We will now discuss the functioning of the EDSEP experiments within the afore-described Dutch, polycentric energy system, based on the criteria from our conceptual framework: control, efficiency, local autonomy, and political representation.

5.2.1. Control

Under the EDSEP, experimenters can carry out several tasks that were not permitted under the current Dutch model. Energy transport and grid management are considered to be a public utility, and production and supply are commercial activities. Without the EDSEP, the experiments can only be active in production and supply. However, supply requires a specific permit and it is not feasible for most local energy cooperatives or HOA’s due to the required scale of customer base and financial risk. Before 2014, most of the energy cooperatives that acted as supplier sold electricity through energy companies as reseller, while using a so-called white label construction [35]. Others outsource tasks, such as administration and balance responsibility, to a back office of one of these companies while still using their own brand and image [36].

With a derogation, experiments can take over the tasks of both the energy supplier and the DSO, to the extent that they deem to be most beneficial for their projects. Note that derogations only apply to specific articles of the Electricity Act [23]. Other laws and regulations, such as the General Data Protection Regulation, continue to be applicable. In short, the derogation presents the following opportunities to derogate from the Electricity Act

- derogation from the prohibition to carry out DSO tasks;

- derogation from the obligation to have a supply permit;

- freedom to determine grid tariffs, tariff structures, and requirements as set by ACM. ACM only checks the method by which the tariffs are determined, not the tariff itself;

- derogation from certain specific rules that apply to data processing (which are mainly about the requirement to participate in sector-wide discussions to align data related procedures to the benefit of the consumer);

- derogation from certain specific rules regarding transparency and liquidity of the energy market (which are mainly about the right of the government to create additional requirements regarding supply conditions and information provision in case of an illiquid market); and,

- derogation from rules regarding metering device requirements.

There are regulations that limit the control of the experiment. One of these that poses a particular threat to the experimenters is the European Union (EU) legal obligation to provide third-party access to a network whether it is a public or a private network (see article 32 Third electricity directive, 2003/54/EG. Pb EU L 211/55.). This means that participants need to be able to choose another energy supplier. From the perspective of the experimenters, this third-party access is a threat, because it can undermine the business model, as only as much energy is allowed to be generated as the projected use of the participants [23]. Moreover, collective energy management and storage are at risk when the user group decreases. The installations are dimensioned to supply for the initially projected users, and part of the production capacity can potentially not be used anymore if the user number decreases. A reason for this is that the government wants to keep the experiments as self-contained as possible to minimize the risk of blackouts or safety issues in surrounding areas.

Secondly, the prohibition of a flexible transport tariff limits the control of the experiments. Currently, it is only allowed for the DSO to charge a fixed daily transport tariff that is proportional to the capacity of the grid connection [37]. This limits the attractiveness of balancing, as the DSO cannot vary the costs based on the actual used capacity.

Finally, non-energy legislation can also limit the control of experiments over their project. For instance, project grids are only attractive when there is no existing grid and, therefore, go along with the development of houses or apartments. The experimenters then need to obtain a building permit and might need to obtain permission from an aesthetics committee of the built environment. For instance, for Collegepark Zwijsen it was hard to get the design with solar collectors on the façade approved, as it was first deemed to negatively affect spatial quality.

5.2.2. Efficiency

Having an experiment under the EDSEP can lead to a number of cost savings for the participants. We list the most important below [38]:

- Grid connection and DSO transport costs for project grids: A one-time saving on the grid connection costs can be realized. Experimenters that newly construct a grid can save costs, because one high-volume connection to the regional grid is cheaper than the sum total of connections for individual dwellings to the regional grid. This is a financial incentive to balance the energy on project grids, because, the smaller the connection with the regional grid required, the lower the connection costs. Furthermore, the periodical transport costs that need to be paid to the DSO are also lower when the capacity of the connection is lower. This can result in a rather significant saving as the DSO costs are about 1/3 of the total electricity bill.To give an example: The total of the DSO tariffs for a household with an average 3 × 25 A connection at the DSO Stedin € 230.36 (other DSOs do not differ much in their tariffs) [39]. Schoonschip annually pays € 6759.74 according to their business model, which comes down to an average of € 225.32 per dwelling. As this is an all-electric neighborhood, where the electricity consumption is higher, the balancing brings these dwellings back to rather average DSO costs).However, if dwellings do not have their own connection to the grid, they miss out on the annual levy rebate for a part of the energy tax.

- DSO transport costs for large grids: the periodical transport costs on a large grid can be reduced by creating a virtual connection through a shared code for a group of participants that cooperate to create balance. The lower the required peak capacity, the lower the transport costs. Additional costs can be saved by helping the DSO to realize a flat usage profile (using the same capacity of the grid throughout the day), because this has value to the DSO. However, sufficiently adjustable capacity is needed for this.

- Energy tariff of large net: If the experiment can realize the aforementioned flat usage profile, it can potentially negotiate a lower tariff for the energy that it does not generate with its own capacity and needs to buy from an external supplier.

- Fixed supplier costs: Most energy suppliers charge a fixed supply tariff. If the experiment (project grid or large experiment) has one connection, these costs are lower than when each individual user would need to conclude a contract with the supplier. However, costs need to be made to measure the usage within the project and bill the participants.

When the EDSEP started, not all of the decision-making units were familiar with the regulation, because RVO did not prepare them for working with the EDSEP. This led to various instances when the experimenters needed to explain the regulations to the DSOs, ACM, and the tax authority. The compartmentalization of DSOs had a negative impact on the progress of projects, because the functioning of decision-making units within DSOs was not always well aligned. Accordingly, after informing and convincing the civil-servants in one unit, experimenters met with resistance of the executive staff, and had to re-explain their plans. RVO has asked organizations that have dealings with EDSEP-experiments to assign a case-manager with whom the projects can communicate at an early stage to improve this situation.

The scale is another efficiency related factor. It is questionable whether the experiments are an interesting party for the DSO to do business with for grid balancing. Grid operators could for example contract experimenters to make use of their storage capacity, or compensate them for the investment costs of grid reinforcement that are avoided by the experiment. However, some grid operators prefer to deal with larger parties and find projects with a size of up to 10,000 households too small and not very interesting to buy flexibility from. The creation of a legal requirement to buy balancing services through tendering could be a solution here, giving priority to small-scale providers. Or oblige DSOs to buy local balancing services for a price that reflects their value. Historically, such a similar obligation has been embedded in the law for DSOs regarding grid connection to make sure energy production and consumption would be accessible at any location in the country.

Furthermore, energy tax needing to be paid twice for stored energy is a major inefficiency [40] (once when the electricity is uploaded in a battery and once when it is taken out again). As the energy tax is a high proportion of the energy price (see footnote 5), this limits experimentation with storage solutions. Unfortunately, alignment between the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate and the Ministry of Finance to avoid this double taxation has been lacking. In the near future, this problem will no longer occur, because the EU has adopted the ‘Clean Energy for all Europeans’ package, which states that owners of storage facilities should not be subject to any double taxation [41].

Additionally, the interpretation of current energy tax rules makes the experiments less efficient. Energy tax can be saved if the ownership structures make sure that there is no supply to third parties, and the participants make use of their own production and distribution capacity. However, a third party is a party with a different real estate valuation tax object, according to the taxation criteria (REV-object, in Dutch: woz-object). Each house or apartment is a REV tax object, and, therefore, energy tax on electricity needs to be paid when a participant uses energy from the production installation of another participant. A possible solution would be for the municipal government to register the houses as one REV-object (this has no consequences for the REV-tax and the procedure is the same as for other REV-tax objects with multiple owners).

Moreover, whilst DSOs embrace the goal of the EDSEP to keep production and consumption local, they fear that private project grids threaten the socialization model that underlies Dutch grid management. The DSOs have the perception that some experiments are motivated by the evasion of the energy tax, as it appeared at first to some participants that this tax would not apply for the experiments.

Last, but certainly not least, the experimenters need to fully comprehend a whole gamut of complicated energy related regulation to be successful. Misinterpretation can lead to a worsening of the business model and can, ultimately, lead to an inviable project. Experimenters progressed slowly despite some support from RVO and Hieropgewekt due to this complexity. Slow progress even led to the strange situation that the government has decided to draft a follow-up EDSEP without waiting for the formal evaluation of the present experiments.

5.2.3. Local Autonomy

Formally, for experimenters, the two structures to self-organize and function as a decision-making unit in the polycentric energy system are HOA and cooperative.

While HOA and cooperative seem to be structures that are explicitly designed for high commitment of the involved households, these do not, per se, imply a high level of participation of all participants. For example, Endona is a cooperative, but only its board members are members to keep decision-making with the daily management. The organizational structure is primarily set up to run the sub-projects efficiently, it is not geared to involve many local participants. A second example is Collegepark Zwijsen, which was designed without input from its future inhabitants. The derogation was applied for by its project developer, but assigned to the HOA, which was not yet in existence at that time. The HOA only started its regular meetings after the residents started living in the apartments. From then on, the autonomy of the HOA will be larger, as it will decide on topics, such as maintenance and tariffs.

The other two HOA’s, Aardehuizen and Schoonschip, functioned from the beginning of the projects as decision-making units run by the future inhabitants. Both outsourced tasks to professional parties, but took the decisions about project design themselves. The working groups prepared proposals about e.g., sustainability, but these decisions were then taken collectively.

All of the projects, except Zwijsen, which is entirely professionally developed, mention that working as a HOA or a cooperative with participation based on the input of volunteers, who are mostly not professionals in the field of energy, has made it harder to function as a local decision-making unit, because they need to invent the wheel by themselves and it was not always easy to acquire all of the required information for informed choices. Additionally, in the communication with other decision-making units such as DSOs, the tax service and ACM, the status as cooperative or HOA was by times a disadvantage and they needed to first convince the other parties of their know-how and professionality.

5.2.4. Political Representation

The municipal government was the political body that was most involved in the projects. Sometimes the relationship with the local government depended on the political tide, but most projects had a productive working relationship with the municipality and felt supported. Two projects got a municipal subsidy: Endona for a feasibility study for its solar park, Schoonschip a contribution per household for the high energy efficiency of the houses.

Additionally, motions at the local council functioned as a mechanism to realise political representation of the interests of projects in local politics. Aardehuizen and Collegepark Zwijsen both benefited from political motions. Aardehuizen benefited from a motion about sustainable building prior to the project, which helped to increase the support for the project. The project developer of Zwijsen successfully lobbied for a motion that would reduce the fee for the building permit, which is proportional to the building costs and was high due to the costs of the energy sustainability measures and techniques. The project developer was also successful in lobbying to overrule the negative advice of the aesthetics committee for the built environment, so Zwijsen could have its solar collectors.

Furthermore, Endona, Aardehuizen, and Schoonschip received a provincial subsidy, e.g., to hire an architect or for feasibility studies. Aardehuizen also received a European subsidy for the community building, although this had to be partly paid back, as the building could not be realised in time.

At the national level, no specific representation of the experiments exists. RVO reports on their progress to the ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate, but only from their position as an executive organisation, not as lobbyists. For this reason, it is unlikely that the experiences of the experimenters will be influential in the revision of energy law, especially because the experimenters were not asked for their input during the consultation for the draft of the follow-up executive order.

6. Conclusions and Discussion

We studied the EDSEP as an example of a regulatory sandbox, a participatory experimentation environment for exploring the revision of the Electricity Act. When projects receive a derogation under the EDSEP, they can perform new tasks and combine roles that are otherwise legally separated and thereby deliberately unbundled to protect the consumer and safeguard security of supply, affordability, and safety. On the one hand, the project grids can act at the same time as the supplier, producer, and distributor of energy, managing an own mini grid. On the other hand, the large experiments cooperate with the DSO, while the grid remains owned by the grid operator, and are concerned with flattening the usage profile and balancing supply and demand.

By taking on these tasks, experimenters become part of a polycentric energy system with decision-making units at several levels. Interested in their functioning, we asked ourselves the question: What can be learnt about local energy initiatives’ bottom-up experimentation with smart grids in a polycentric energy system? In this section, we conclude on our findings and discuss our conceptual framework, and then put these in a broader perspective of legal innovation for energy transition.

6.1. Lessons Learnt from Participative Experimentation under the EDSEP

For potential experiments, the EDSEP has shown to be a complicated procedure with limited attractiveness for local energy initiatives, which resulted in only 18 experiments of the potential 80 in a four-year period. We want to make four main points, related to the four criteria for the well-functioning of polycentric decision-making structures.

• Efficiency: Combining exemptions with a pro-active nurturing of experimentation

The EDSEP’s exemptions should make the integration of RE and grid balancing more attractive, which adds to the overall efficiency of the energy system. The EDSEP enables taking on new roles, but taking on these roles is hardly attractive or facilitated in the polycentric constellation. First, our case studies show that the EDSEP provides only a modest improvement for the business case of smart grids at the project grid level, and that for the large experiments we studied a good business case has not yet been found due to the limited financial attractiveness and the large organizational capacity required for taking on the balancing and supply roles while they come with considerable financial risks.

Second, for developing the experiments, there is no financial support available and, therefore, the experimenters have to rely solely on their own political efficacy and networking capacities to attract subsidies, or partners with knowledge or capital to invest. RVO has an important task to distribute subsidies for energy innovations, especially for innovations in the early stages. Hence, a special fund or subsidy for experiments would fit in seamlessly in the overall aims of the RVO. In addition to this, we suggest that more support should be created to overcome knowledge differences in small-scale volunteer organizations.

Third, alignment between decision-making units, such as the DSOs, ACM, and the experiments, was initially lacking due to poor communication with the other actors about the regulation by RVO, which made it harder to establish a productive collaboration with these decision-making units. This reduced the efficiency of experimentation, as enrolling such established actors in their network is very beneficial for bottom-up technological innovation projects [42].

Hence, our findings suggest that the smart-grid niche that the EDSEP provides lacks sufficient nurturing to function efficiently [43]. Nurturing can take place through assisting learning processes, articulating expectations, and helping networking processes [43]. All of these could be strengthened to increase the efficiency of the polycentric constellation that is created under the EDSEP.

• Control: the benefits and limitations of the new roles

The EDSEP fulfills a need to explore regulation that better facilitates the integration of intermittent resources. By making use of the EDSEP, the experimenters can take on new roles as grid managers (for project grids even the role of grid owners is possible) and as energy suppliers. For project grids, we saw that this incentivizes grid balancing through providing the opportunity to bring down the DSO costs by minimizing the exchange of energy (import or export) between the project grid and the regional grid. Additionally, the exemption from getting a supply permit is used for the project grids, but, in both cases, the administration has been outsourced to either an energy company or a company related to the project developer. These tasks require more time and expertise than the local initiatives could give and, therefore, they chose to outsource the tasks to commercial organizations.

Taking on the roles of supplier and balancing agent is more difficult when it comes to extra control for the large grids. First, when it comes to supply, the customer base is bigger than for the small projects, so the risks of, for instance, late payments are also higher, but the company is still not big enough (or not sure whether it is in the case of Endona) to carry these risks. Second, when it comes to taking the role of grid manager for a larger area, this is complicated due to the fact that for flattening the usage profile, adjustable capacity is required to create a good business case, which is expensive for experimenters, as it has to come largely from storage because they cannot use industrial partners’ capacity, as their participants have to be mainly households. Furthermore, as only the local experimenters could experiment with tariff structures and the regional DSOs not, business opportunities regarding balancing are limited. Lastly, the supplier role of the BRP is out of reach for the experimenters, as the software for this is too expensive and the risks too high for the small-scale experiments.

Thus, having the opportunity to take more control over the local energy system from a legal perspective does not always mean that all of this control can be taken over and all new roles can be enacted. Some of the tasks are not (yet) feasible, mostly due to financial, organizational, practical, or sometimes legal constraints. However, despite the fact that experimenters cannot take full control, the EDSEP provides end-user collectives with an incentive to balance their grid, e.g., enabling p-2-p supply without intervention of a DSO.

• Political representation: approach sustainability more holistically in policymaking

Experimentation would have been more effective if the Dutch tax authority was enabled by the ministry of Finance to co-experiment and to, for instance, exempt the experiments from double taxation on storage. However, communication regarding the EDSEP between the ministries of Economic Affairs and Climate and Finance was lacking. Some projects have tried to come up with project designs to pay less energy tax. However, no exceptions or reduced tariffs were granted to these relatively small energy cooperatives, in contrast to the tax rulings for large international companies. Hence, similarly to the work of Kooij et al. on niche–regime interactions between the tax authority and collective PV producers, our case also ‘illustrates the political and power-laden nature of sustainability transitions, going beyond the focus on organizational and technological challenges’ [44] (p.10). Ultimately, the EDSEP-sandbox shows that an experiment is not always fully a two-way regulatory dialogue between an experimenter and a regulator.

Furthermore, the lack of alignment between ministries shows that the development of policies that affect sustainability evolve in parallel worlds, and a more holistic approach is needed [1]. Stepping away from silo thinking and strengthening inter-ministerial alignment would be helpful in designing effective energy transition policies. Stronger political representation of a lobby organizations or intermediaries [45,46] at the national level would also be useful in this case. For instance, EnergieSamen, a Dutch lobby organization for local energy initiatives, could take on such a role.

• Local autonomy: a legislative balance between self-responsibility and the protection of consumers

The experiments show that, while the HOA and cooperative seem to be structures that are explicitly designed for high commitment of the involved households, these do not, per se, imply a high level of participation by all participants. In the context of smart electricity, energy legislation needs to strike the balance between opportunities for self-responsibility and the protection of consumers [1]. Options for users to shape their own energy system are desirable in the context of energy democracy [26], but consumer protection against high prices could be threatened, e.g., when making tariffs flexible. Therefore, further experimentation with legal innovation should not only explore how legalislation can be facilitative of technological innovation, but also of social innovations to create an energy system that represents the interests of its users and is acceptable to them. Involving local energy initiatives or users cannot function as the sole mechanism of user involvement, because our cases show that such a characteristic does not always guarantee high participation. Furthermore, adequate insight of end users in the experiment necessary to protect their interests might be lacking.

6.2. Theoretical Reflection on Polycentricity

The advantage of the concept of polycentricity is that an actor constellation can be described by four different actor-characteristics (level, type, sector, and function), which provide helpful tools for understanding the context of experimentation. We find that this concept provides more guidance for our study in defining actor roles and their position in the energy system than e.g., the multi-level perspective (MLP), which predominantly focuses on levels and rather general dimensions, such as science, market preferences, technology, socio-cultural, and policy [47]. With the concept of polycentricity, it is easy to see what a nested system of decision-making units looks like and in which ways it is layered, whereas MLP puts more focus on which sectors (market, science, policy, etc.) are represented in a system.

Furthermore, the concepts for evaluating the role of actors in polycentric systems (local autonomy, control, efficiency, and political representation) help to understand what is necessary for a decision-making unit in such a system to function well. They were especially helpful when studying legal innovations due to the inclusion of the concepts of control and political representation. The same goes for studying participative bottom-up innovation due to the inclusion of local autonomy. Lastly, the concept efficiency helps to understand whether the decision-making unit can provide added value to the system, which is a useful indicator in assessing whether sustainability experiments contribute to an efficient progress towards a more sustainable energy system.

However, it needs to be realised that, while using these concepts, the success of the experimenters in the polycentric context does not equal the value of the experiment for legal innovation. When evaluating the experiments, the question should also be whether the experiment has resulted in new insights for guiding energy transition, in this case study for revising energy law, and not only whether the experimentation constellation itself is efficient in providing added value. Learning potential, instead of replication potential, should be central in evaluating experimentation for legal innovation.

Furthermore, the analytical framework is focused on the functioning of the polycentric system, but does not give theoretical guidance on what actors can do to nurture experimentation, or how they can better work together and create alignment in the system. Strategic niche management and actor-network theory may be helpful frameworks to further explore these aspects of innovation management.

6.3. Final Remarks

For the Dutch legislators, learning from the EDSEP experiences is important, because the EDSEP is only the start of experimentation informing revisions of energy law. A follow-up of the EDSEP has already been drafted, being based on the 2018 Law Progress Energy Transition. This executive order expands the size of experiments, experimenting actors, and also enables experiments under the Gas Act. The new regulation has been presented to the parliament in May 2019 and new experiments can apply once the new executive order has received positive advice of the Council of State, which is expected early 2020.

We would like to briefly summarize the conclusions of this study, so they can be taken into account for the evaluation of the EDSEP as well as for future experimentation. Experimentation under the EDSEP shows us that inter-actor alignment was initially lacking and pro-active nurturing would have smoothened the implementation. Furthermore, EDSEP experimenters faced significant constraints, had very limited political representation, and varying representation of the users within the experiment.

As a starting point to improve both the well-functioning of the experiments and the quality of the learning process, an intermediary could be more of a bridge between national and regional actors and the locally operating experimenters, and take a more active role in developing a knowledge base, providing project development support, spreading knowledge in the polycentric experimentation system, and extending the learning community. A first option for this could be an extension of the role of the executive organization, RVO, as it is already involved in the derogation process. In the Scottish context, Community Energy Scotland, which provides such support, also grew from a governmental initiative. Alternatively, the national community energy platform Hieropgewekt could take on this role, or even the regional umbrella organizations for energy cooperatives. Yet, to realize this, such intermediaries should pro-actively follow developments in energy legislation relevant for local energy initiatives and attract or train expert staff that can assist experimenters with their project development. As many of such organizations do not have the financial means for this, a government that truly wants to support inclusive innovation and transition processes should allocate budget to them for staff time.

Thus far, a lot has been expected from the experimenters without much active facilitation. Resultantly, the distribution between the risks of and incentives for experimentation is rather uneven and, therefore, it could have been expected that experimenters’ progress was relatively slow and interest in new roles limited. This decreased the potential of the sandbox for generating lessons for revising energy regulation to facilitate energy transition. A more holistic approach, inter-actor alignment, the availability of expert support by an intermediary, and facilitation of a more close-knit learning community would bring benefits to the bottom-up participatory innovation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.D., T.v.d.S. and E.C.v.d.W.; Methodology, A.M.D. and E.C.v.d.W.; Formal Analysis, A.M.D.; Investigation, A.M.D. and E.C.v.d.W.; Data Curation, E.C.v.d.W.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, V.d. S., T. and V.d. W., E.C.; Writing – Review & Editing, T.v.d.S. and E.C.v.d.W.; Project Administration, E.C.v.d.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and the APC were funded by The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) grant number [313-99-304].

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the interviewees for generously sharing their time, experiences, and knowledge. We would also like to thank Henny van der Windt for his constructive feedback. Furthermore, we are grateful for the constructive feedback of two anonymous reviewers during the publication process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1 displays an overview of EDSEP projects.

Table A1.

Overview of EDSEP experiments.

Table A1.

Overview of EDSEP experiments.

| Year | Name | Type (Project/Large) | Legal Entity | Project Goals | Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Parq Green | P | HOA | Collective PV, sustainable heat | 292 recreational houses |

| Black Jack/Withdrawn | L | ||||

| Experiment DDE Collegepark Zwijsen | P | HOA | Generations, EMS, tariff differentiation, cogeneration | 115 apartments in renovated school | |

| Endona EXP | L | Coop | Generation, cooperation with biodigester, supply to members, increasing direct usage, EMS, storage. | 47 with EMS and towards 5000 members in 10 years | |

| 2016 | Schoonschip | P | HOA | EMS, generation, batteries, heat pumps, heat storage in buffer and smart appliances | 46 water houses |

| Noordstraat 111 Tilburg | P | HOA | EMS, generation, smaller grid connection | 3 houses in old office (owned) | |

| Villa de Verademing | P | Coop | Insulation, generation, smart grid connected to the neighborhood, storage. | 18 apartments and 1 city residence | |

| Groot Experiment Aardehuizen e.o. | L | HOA | Community battery, EVs, EMS, generation, no gas, smart software dynamic electricity tariffs and demand response, p-2-p. | 3 rental and 20 owned | |

| Kringloopgemeenschap Bodegraven-Reeuwijk | L | Coop | Generation and determining own tariff | 2500 households | |

| 2017 | Republica Papaverweg | P | Coop | EMS, generation, own grid, smart charging with EVs, thermal storage and batteries | Newly built housing block with various accommodations |

| Micro Energy Trading Eemnes | L | Coop | P-2-P, EVs, blockchain, storage, generation, smart software. | 100–200 social houses; scaling up to 1500 | |

| Micro Energy Trading Amersfoort | L | Coop | P-2-P, smart software and block chain | 400–600 social houses | |

| 2018 | Duurzame Wijkenergiecentrale Trudo | L | Coop | Generation, EMS, batteries, EV chargers, and tariff differentiation | 260 apartments in old industrial building(owned/rental) |

| Smart Grid Groene Mient | L | HOA | Generation, heat pumps, no gas, battery and EVs | 33 newly built houses (2017) with communal garden | |

| Zeuven heuvels Wezep | P | Coop | EMS, generation, no gas, own grid. | 57 newly built houses | |

| Smart energy grid Bajeskwartier | L | Coop | Generation, neighborhood battery, EVs, heat pumps and thermal storage, smart grid software platform EMS | 950 apartments, school, hotel, 340 student houses and various other services | |

| Kleine Duinvallei Katwijk/ Gave Buren | P | Coop | Balancing, joint electricity purchase and distribution, generation. | 80 ecological houses | |

| Shared energy-mobility community Amersfoort | L | Coop | P-2-P, car sharing with EVs | 400–800 houses of housing cooperation | |

| 2019 | Cooperatie zonnepark Bad Noordzee U.A. | P | Coop | Heat pumps, P-2-P, PV, battery storage. | 322 recreational houses and a few large use connections |

Appendix B

Table A2 displays an overview of interviewed actors.

Table A2.

Overview of interviewed actors.

Table A2.

Overview of interviewed actors.

| Interviewed Actor | Type of Interview |

|---|---|

| Resident of case Schoonschip | Face-to-face |

| Resident of case Aardehuizen | Face-to-face |

| Project developer of case Collegepark Zwijsen | Face-to-face |

| Resident board member and advisor of case Endona | Face-to-face |

| Grid operators from the different territorial jurisdictions, who engage with experiments (3) | Phone (all 3) and one also face-to-face |

| Energy company staff member: EnergieVanOns & Nuts&co. (2) | Phone |

| RVO | Phone |

| Policy maker ministry of Economic Affairs | Phone |

| Tax authority staff member Consultant in legal, technical and fiscal aspects of renewable energy and energy efficiency. Focus on complex projects and political processes. | Phone Face-to-face |

| Employee regional umbrella cooperative for supporting local energy cooperatives | Phone |

| Management, ICT, energy and sustainability advisor, creator of web environment with information overview for EDSEP experimenters | Face-to-face |

References

- Diestelmeier, L. Changing power: Shifting the role of electricity consumers with blockchain technology–Policy implications for EU electricity law. Energy Policy 2019, 128, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallesen, T.; Jacobsen, P.H. Solving infrastructural concerns through a market reorganization: A case study of a Danish smart grid demonstration. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 41, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrijssen, S.; Parra, A.C. Radical prosumer innovations in the electricity sector and the impact on prosumer regulation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edens, M.G.; Lavrijssen, S.A.C.M. Balancing public values during the energy transition–How can German and Dutch DSOs safeguard sustainability? Energy Policy 2019, 128, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, D.; Swierczynski, M.; Stroe, D.I.; Norman, S.A.; Abdon, A.; Worlitschek, J.; O’Doherty, T.; Rodrigues, L.; Gillott, M.; Zhang, X.; et al. An interdisciplinary review of energy storage for communities: Challenges and perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 730–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbong, G.P.J.; Beemsterboer, S.; Sengers, F. Smart grids or smart users ? Involving users in developing a low carbon electricity economy. Energy Policy 2013, 52, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schick, L.; Winthereik, B.R. Innovating relations - Or why smart grid is not too complex for the public. Sci. Technol. Stud. 2013, 26, 82–102. [Google Scholar]

- Planko, J.; Chappin, M.M.H.; Cramer, J.M.; Hekkert, M.P. Managing strategic system-building networks in emerging business fields: A case study of the Dutch smart grid sector. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 67, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteman, M.; Kooij, H.J.; Wiering, M.A. Pioneering renewable energy in an economic energy policy system: The history and development of dutch grassroots initiatives. Sustainability 2017, 9, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proka, A.; Loorbach, D.; Hisschemöller, M. Leading from the Niche: Insights from a Strategic Dialogue of Renewable Energy Cooperatives in The Netherlands. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parag, Y.; Sovacool, B.K. Electricity market design for the prosumer era. Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 16032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, B.P.; Hakvoort, R.A.; Van Oost, E.C.J.; Van der Windt, H.J. Community energy storage: Governance and business models. In Consumer, Prosumer, Prosumager : How Service Innovations Will Disrupt the Utility Business Model; Sioshansi, F.P., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2019; pp. 209–234. ISBN 9780128168363. [Google Scholar]

- Koenders, J.F.; Pipping, S.L. Het Besluit experimenten decentrale duurzame elektriciteitsopwekking doorgelicht. Ned. Tijdschr. Voor Energier 2016, 4, 146–155. [Google Scholar]

- Heldeweg, M.A. Normative alignment, institutional resilience and shifts in legal governance of the energy transition. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OFGEM Insights from Running the Regulatory Sandbox|Ofgem. Available online: https://www.ofgem.gov.uk/publications-and-updates/insights-running-regulatory-sandbox (accessed on 31 October 2019).

- Ostrom, V.; Tiebout, C.M.; Warren, R. The Organization of Government in Metropolitan Areas : A Theoretical Inquiry. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1961, 55, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005; ISBN 9780691122380. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Polycentric systems for coping with collective action and global environmental change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2010, 20, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Schoor, T.; Scholtens, B. Scientific Approaches of Community Energy, a Literature Review; CEER: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- SER Energieakkoord voor Duurzame Groei. Available online: https://www.energieakkoordser.nl/energieakkoord.aspx (accessed on 13 August 2019).

- Ministerie van Economische Zaken en Klimaat. Voorstel van wet Houdende Regels Met Betrekking Tot de Productie, het Transport, de Handel en de Levering van Elektriciteit en gas (Elektriciteits- en Gaswet); Ministerie van Economische Zaken en Klimaat: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2014.

- Artikel 7a Elektriciteitswet 1998. Available online: https://maxius.nl/elektriciteitswet-1998/artikel7a/ (accessed on 28 September 2019).

- Wetten.nl Regeling: Besluit Experimenten Decentrale Duurzame Elektriciteitsopwekking - BWBR0036385. Available online: https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0036385/2015-04-01 (accessed on 6 September 2019).

- Goldthau, A. Rethinking the governance of energy infrastructure: Scale, decentralization and polycentrism. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2014, 1, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammers, I.; Diestelmeier, L. Experimenting with Law and Governance for Decentralized Electricity Systems: Adjusting Regulation to Reality? Sustainability 2017, 9, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammers, I.; Arentsen, M. Polycentrisme in lokale besluitvorming over duurzame energie: De casus slimme netten. Bestuurswetenschappen 2016, 70, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinnis, M.D. An introduction to IAD and the language of the Ostrom workshop: A simple guide to a complex framework. Policy Stud. J. 2011, 39, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research : Design and Methods, 5th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013; ISBN 1483322246. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N.; Terry, G. Thematic analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2019; pp. 843–860. ISBN 9789811052514. [Google Scholar]

- GridFlex Initiatief Gridflex Heeten : GridFlex. Available online: https://gridflex.nl/over-gridflex/ (accessed on 8 October 2019).

- CWI Grid Friends–Demand response for grid-friendly quasi-autark energy cooperatives. Available online: http://www.grid-friends.com/ (accessed on 8 October 2019).

- Zomerman, E.; Van Der Windt, H.; Moll, H. The distribution systems operator’s role in energy transition: Options for change. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2018, 217, 411–422. [Google Scholar]

- Belastingdienst Tabellen Tarieven Milieubelastingen. Available online: https://www.belastingdienst.nl/wps/wcm/connect/bldcontentnl/belastingdienst/zakelijk/overige_belastingen/belastingen_op_milieugrondslag/tarieven_milieubelastingen/tabellen_tarieven_milieubelastingen?projectid=6750bae7-383b-4c97-bc7a-802790bd1110 (accessed on 28 September 2019).

- CBS StatLine - Aardgas en Elektriciteit, Gemiddelde Prijzen van Eindverbruikers. Available online: https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/81309NED/table?fromstatweb (accessed on 28 September 2019).

- Van Der Schoor, T.; Van Lente, H.; Scholtens, B.; Peine, A. Challenging obduracy: How local communities transform the energy system. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hieropgewekt Wat Kan Een Energiebedrijf Voor Een Initiatief Betekenen? Ruggensteun Energiebedrijven Een Zegen Voor Lokale Initiatieven? Available online: https://www.hieropgewekt.nl/sites/default/files/documents/Watkaneenenergiebedrijfvooreeninitiatiefbetekenen.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2019).

- Enexis Uitleg Tariefopbouw Netwerkkosten. Available online: https://www.enexis.nl/consument/aansluiting-en-meter/tarief/uitleg-tariefopbouw (accessed on 13 January 2020).

- HIER Opgewekt Waarom Meedoen Met de Experimentenregeling? Available online: https://www.hieropgewekt.nl/kennisdossiers/waarom-meedoen-met-experimentenregeling (accessed on 6 September 2019).

- Stedin Tarieven. Available online: https://www.stedin.net/tarieven#3x25 (accessed on 7 January 2020).

- Smart Storage Magazine Staatssecretaris Snel: Problematiek Dubbele Belasting bij Energieopslag per 2021 Oplossen Door Wetswijziging. Available online: https://smartstoragemagazine.nl/nieuws/i18940/staatssecretaris-snel-problematiek-dubbele-belasting-bij-energieopslag-per-2021-oplossen-door-wetswijziging (accessed on 28 September 2019).

- European Parliament Texts Adopted - Common Rules for the Internal Market for Electricity. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-8-2019-0226_EN.html (accessed on 22 October 2019).

- Van der Waal, E.C.; van der Windt, H.J.; van Oost, E.C.J. How local energy initiatives develop technological innovations: Growing an actor network. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Raven, R. What is protective space? Reconsidering niches in transitions to sustainability. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 1025–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooij, H.-J.; Lagendijk, A.; Oteman, M. Who Beats the Dutch Tax Department? Tracing 20 Years of Niche–Regime Interactions on Collective Solar PV Production in The Netherlands. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, T.; Hielscher, S.; Seyfang, G.; Smith, A. Grassroots innovations in community energy: The role of intermediaries in niche development. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 868–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hielscher, S.; Seyfang, G.; Smith, A. Community Innovation for Sustainable Energy; CSERGE Working Paper; Centre for Social and Economic Research on the Global Environment (CSERGE): Norwich, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W. The multi-level perspective on sustainability transitions: Responses to seven criticisms. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2011, 1, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).