Graphene and Lithium-Based Battery Electrodes: A Review of Recent Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Graphene and Graphene Related Materials Properties

2.1. Inside Mechanical Properties of Graphene

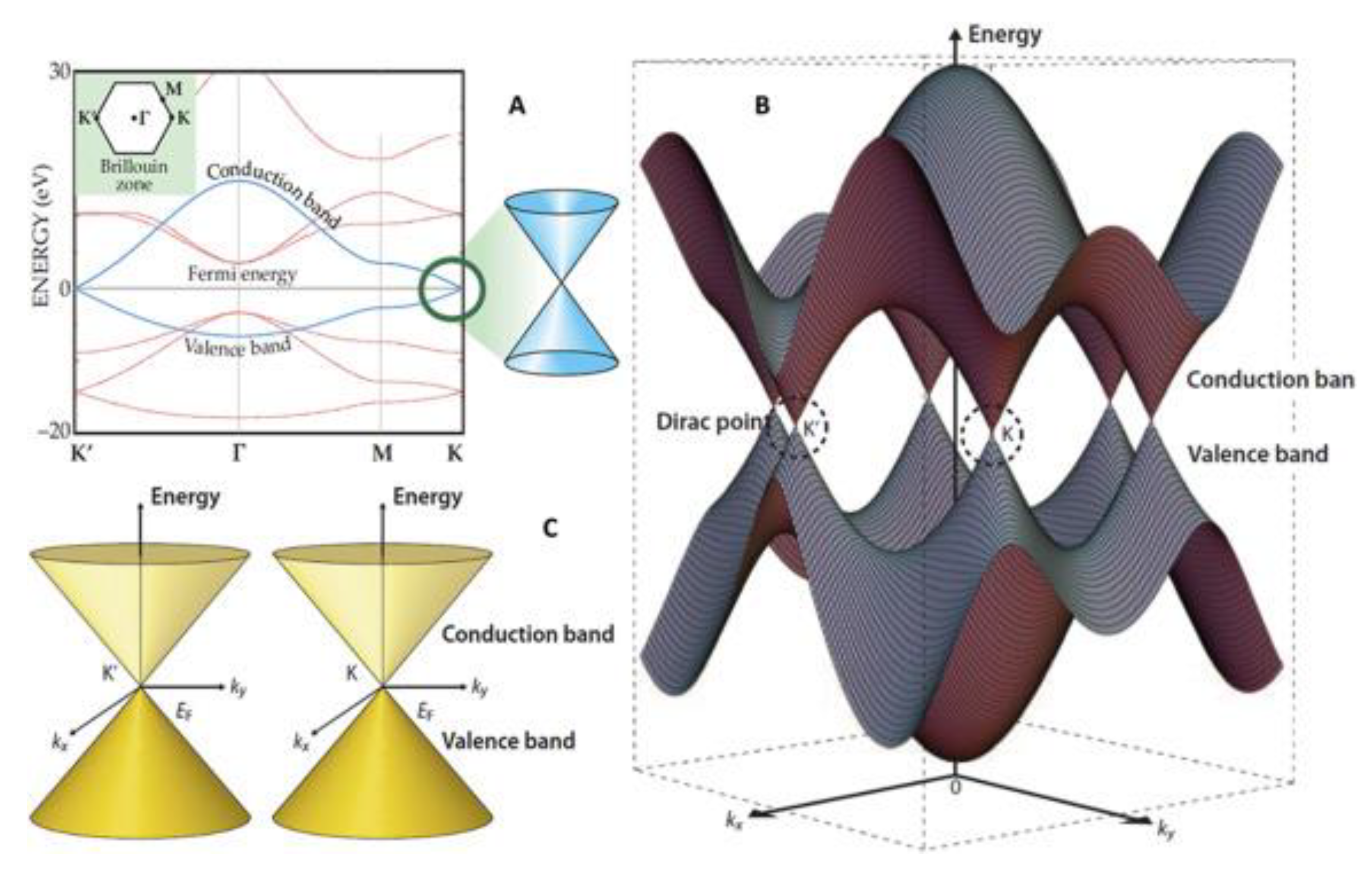

2.2. The Electrical Properties of Graphene

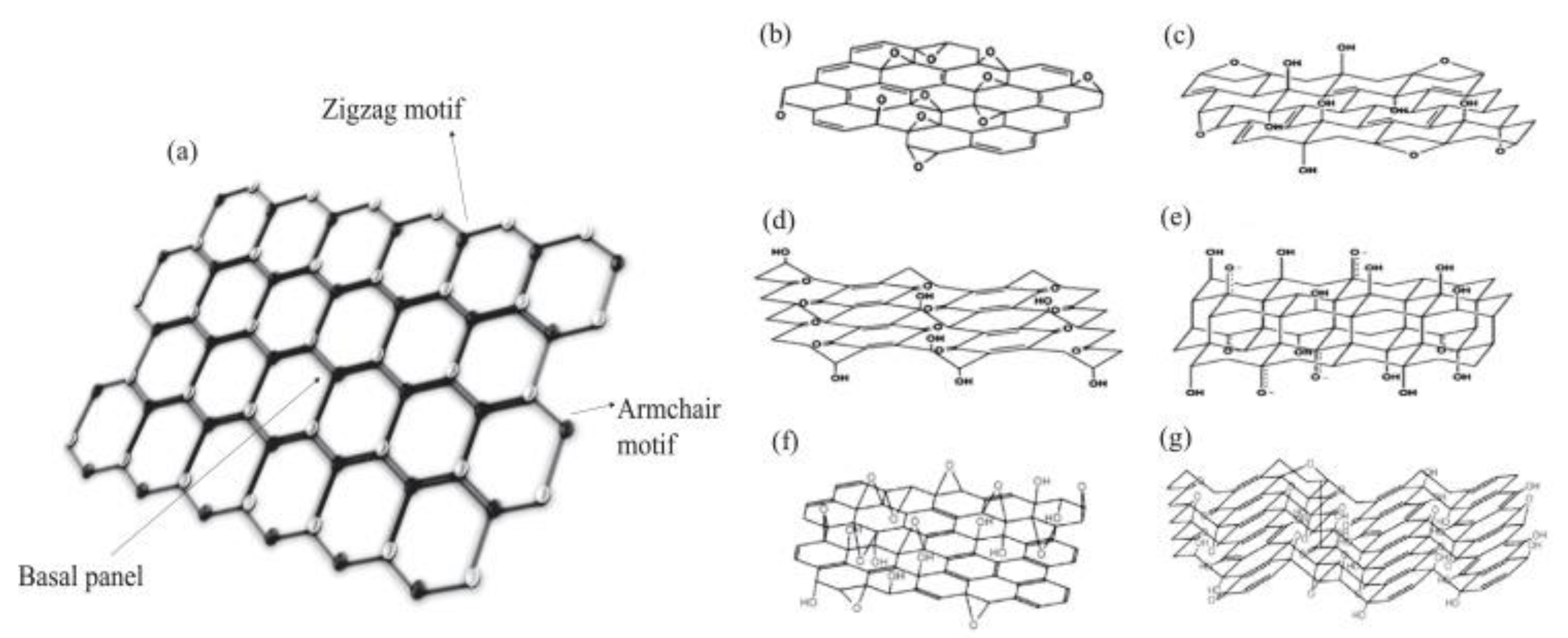

2.3. Graphene Related Materials: An Overview

2.4. Graphene and Related Materials: Productive Processes

2.4.1. Micromechanical Cleavage

2.4.2. Liquid-Phase Mechanical Exfoliation

2.4.3. Chemical Cleavage and Exfoliation

2.4.4. Chemical Vapor Deposition

2.5. Consideration on Cost-Effectiveness of Graphene and Related Materials

3. Graphene and Graphene Related Materials in Secondary Batteries

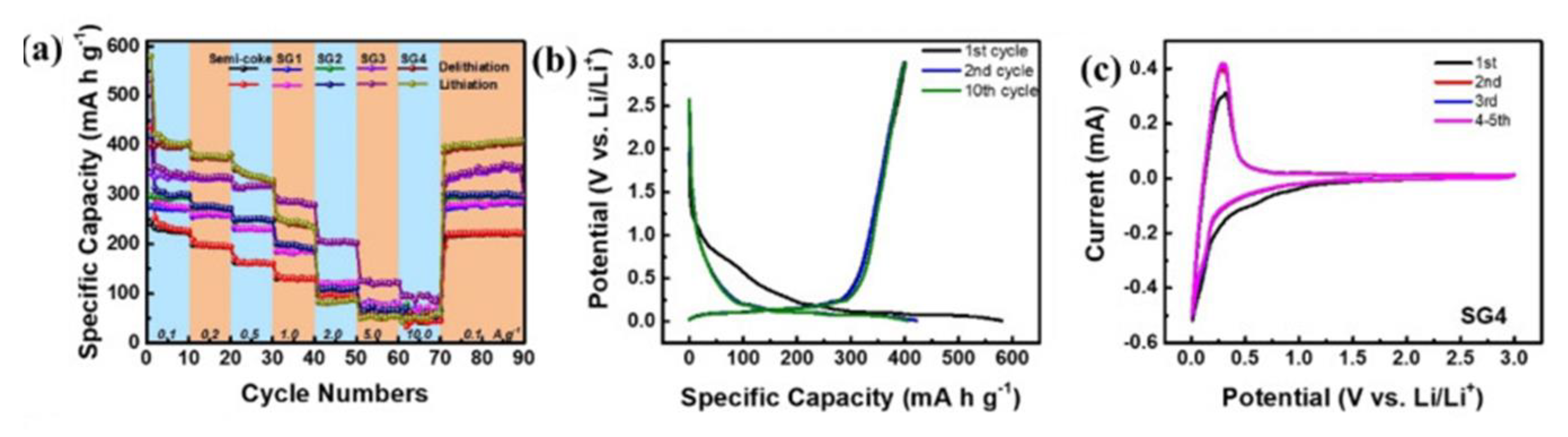

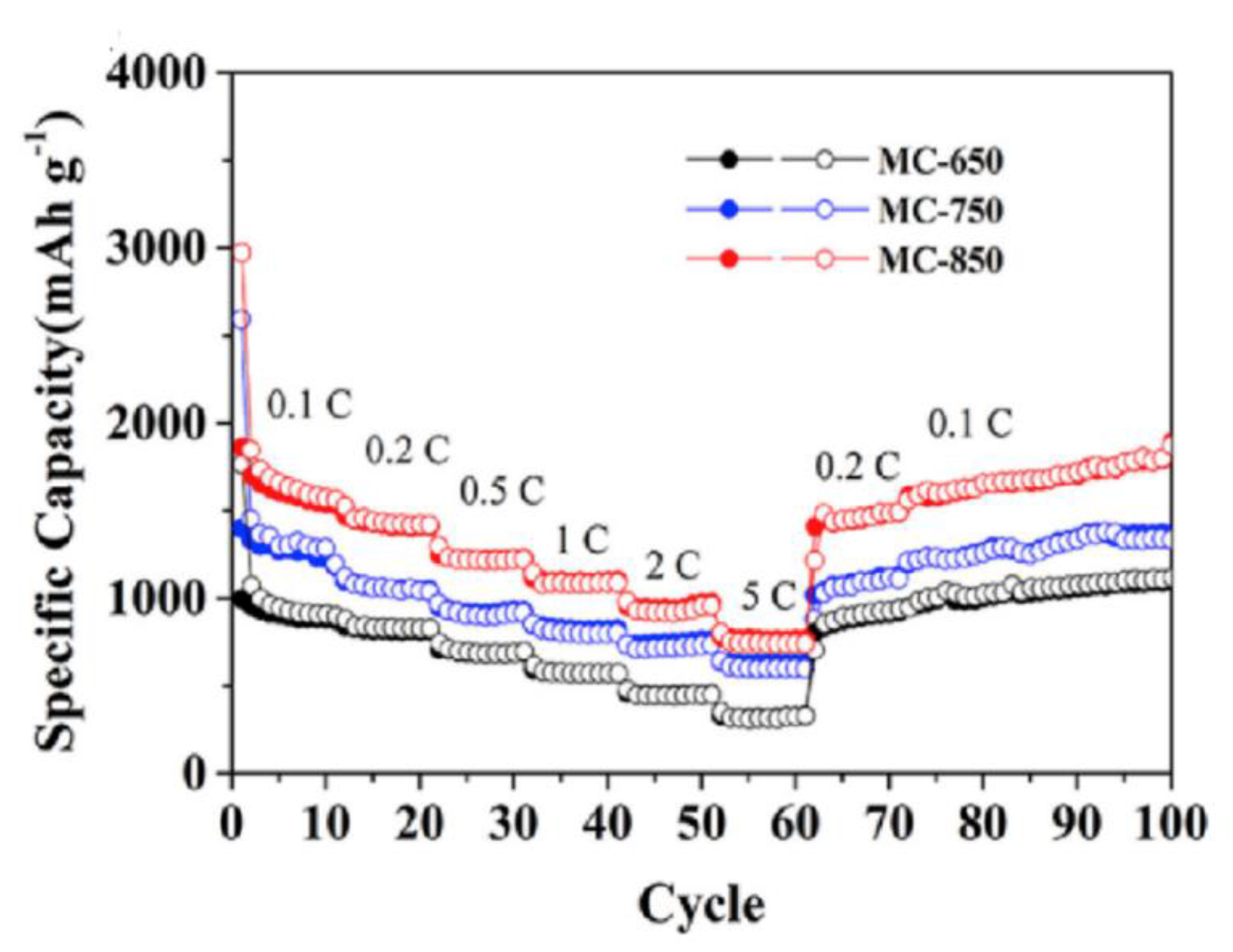

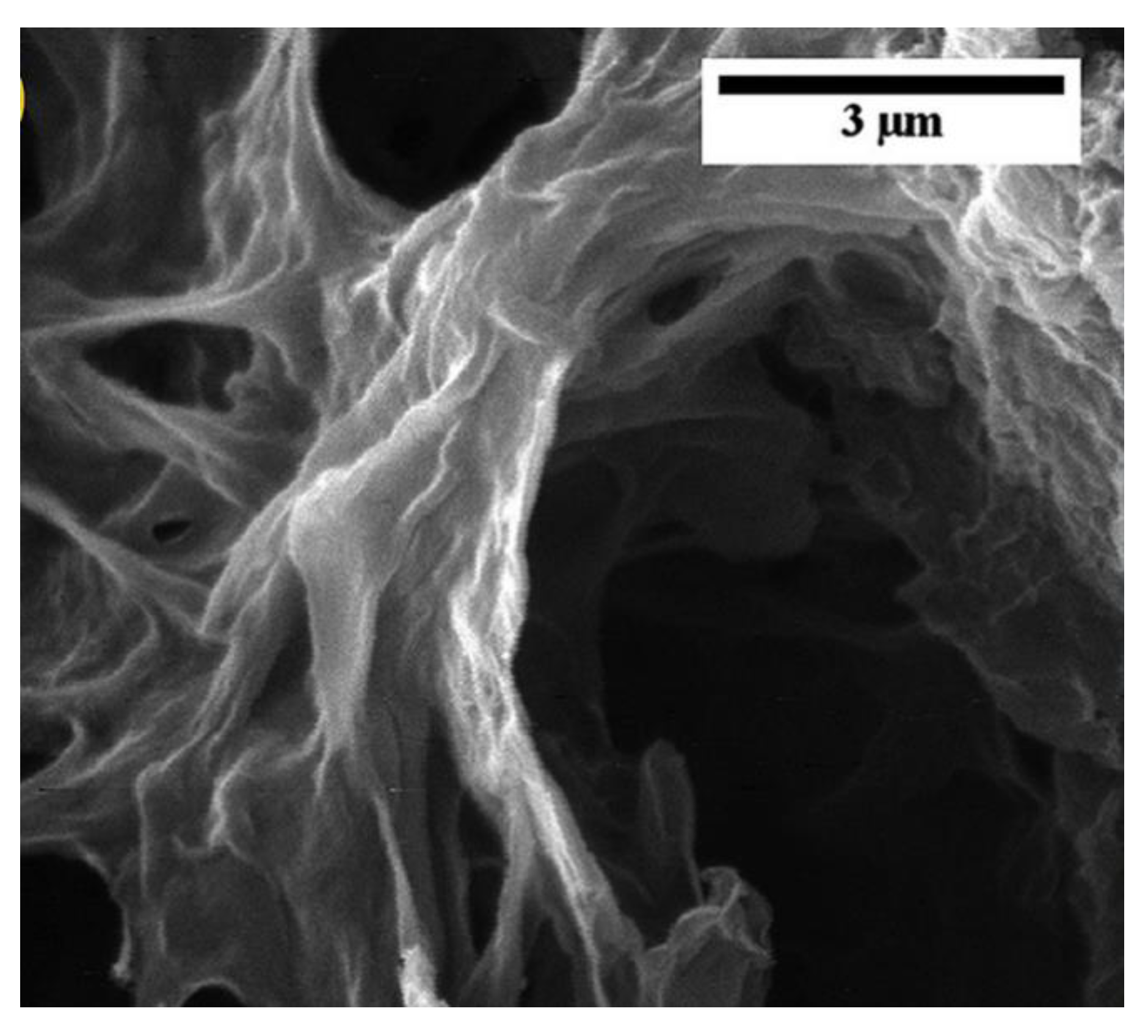

3.1. Pristine Graphene and Related Materials

3.2. Doped Graphene and Related Materials

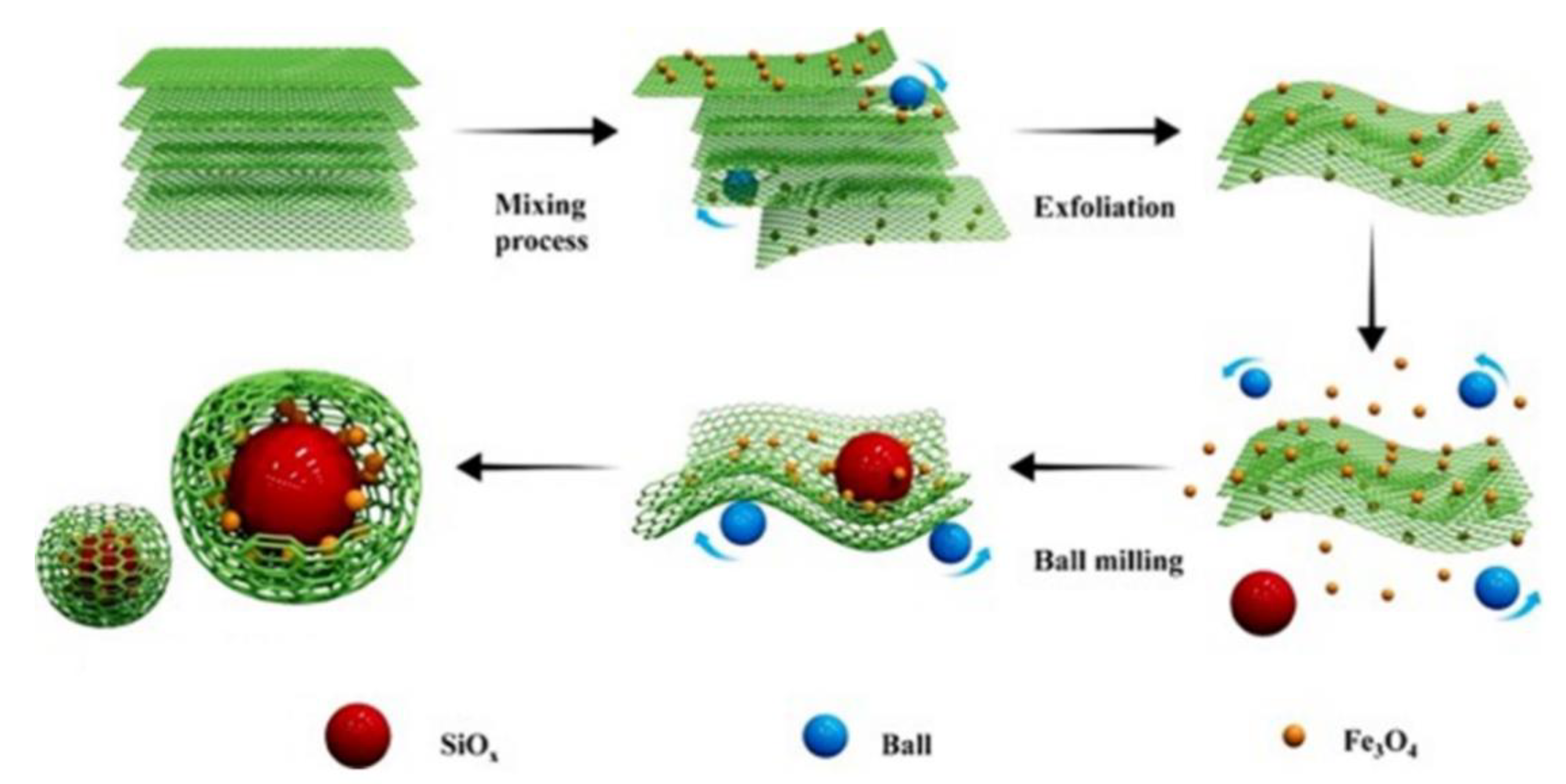

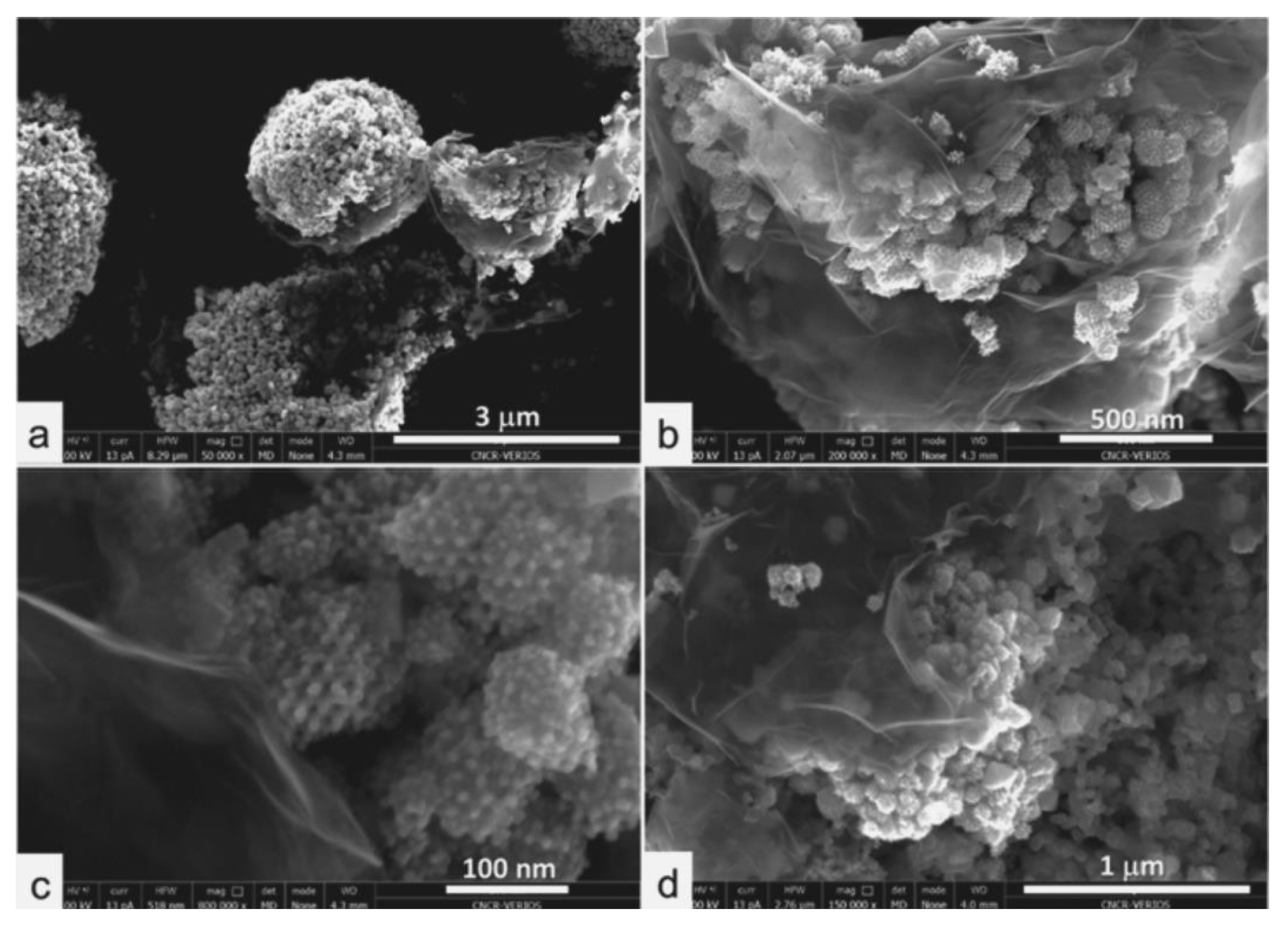

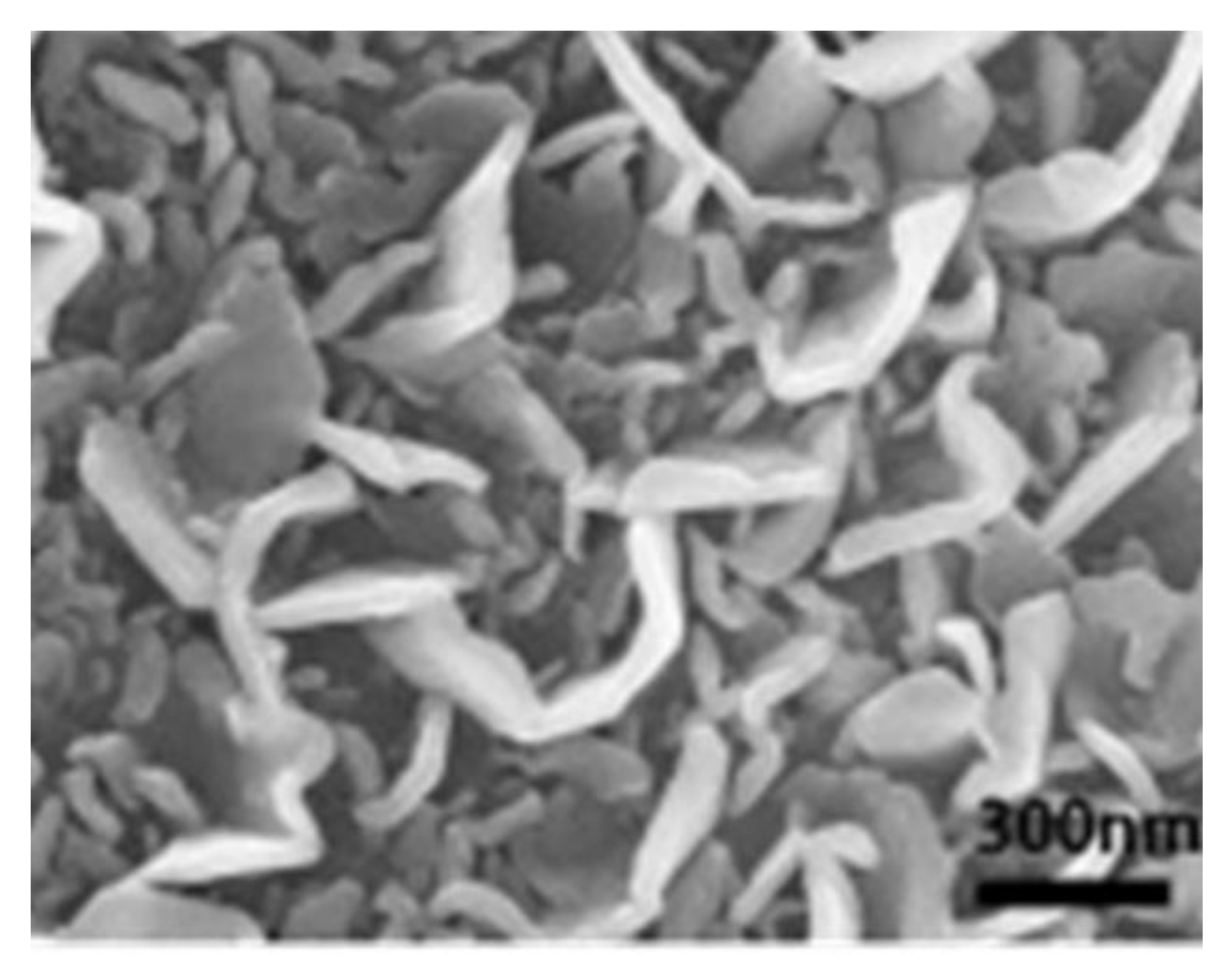

3.3. Tailoring Graphene with Inorganic Nanoparticles for the Production of Nanocomposite Materials

4. A Brief Perspective on the Future of Graphene and Related Materials for Battery Applications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wei, D.; Kivioja, J. Graphene for energy solutions and its industrialization. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 10108–10126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavagna, L.; Marchisio, S.; Merlo, A.; Nisticò, R.; Pavese, M. Polyvinyl butyral-based composites with carbon nanotubes: Efficient dispersion as a key to high mechanical properties. Polym. Compos. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, K.; Dixit, A.R. A review of the mechanical and thermal properties of graphene and its hybrid polymer nanocomposites for structural applications. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 5992–6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadkhah, M.; Saboori, A.; Fino, P. An overview of the recent developments in metal matrix nanocomposites reinforced by graphene. Materials 2019, 12, 2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo-Manrique, P.; Lei, X.; Xu, R.; Zhou, M.; Kinloch, I.A.; Young, R.J. Copper/graphene composites: A review. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 12236–12289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siochi, E.J. Graphene in the sky and beyond. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2014, 9, 745–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavagna, L.; Burlon, D.; Nisticò, R.; Brancato, V.; Frazzica, A.; Pavese, M.; Chiavazzo, E. Cementitious composite materials for thermal energy storage applications: A preliminary characterization and theoretical analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, A.K.; Lund, I.; Puri, Y.R.; Efstathiadis, H.; Haldar, P.; Dhar, N.K.; Lewis, J.; Dubey, M.; Zakar, E.; Wijewarnasuriya, P. Review of Graphene Technology and Its Applications for Electronic Devices; Graphene—New Trends Development: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Balandin, A. Toward ubiquitous environmental gas sensors-capitalizing on the promise of graphene. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, G.; Bi, Z.; Zhang, R.; Liu, J.; Yu, X.; Li, Z. A comprehensive review on graphene-based anti-corrosive coatings. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 373, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nine, M.J.; Cole, M.A.; Tran, D.N.; Losic, D. Graphene: A multipurpose material for protective coatings. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 12580–12602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, A.; Mitra, A.; Mukhopadhyay, S.C. Graphene and its sensor-based applications: A review. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2018, 270, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 15 years of graphene electronics. Nat. Electron. 2019, 2, 369. [CrossRef]

- Heerema, S.J.; Dekker, C. Graphene nanodevices for DNA sequencing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2016, 11, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Cui, L.; Losic, D. Graphene and graphene oxide as new nanocarriers for drug delivery applications. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 9243–9257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kady, M.F.; Shao, Y.; Kaner, R.B. Graphene for batteries, supercapacitors and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistoia, G. Lithium-Ion Batteries; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherladns, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshio, M.; Brodd, R.J.; Kozawa, A. Lithium-Ion Batteries; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Woody, M.; Arbabzadeh, M.; Lewis, G.M.; Keoleian, G.A.; Stefanopoulou, A. Strategies to limit degradation and maximize Li-ion battery service lifetime-Critical review and guidance for stakeholders. J. Energy Storage 2020, 28, 101231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panasonic. NCA103450: Lithium-Ion Batteries. Available online: https://industrial.panasonic.com/ww/products/batteries/secondary-batteries/lithium-ion/models/NCA103450 (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Panasonic. NCR18650BF: Lithium-Ion Batteries. Available online: https://industrial.panasonic.com/ww/products/batteries/secondary-batteries/lithium-ion/models/NCR18650BF (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Commission, E. Integrated SET-Plan Action 7, “Become Competitive in the Global Battery Sector to Drive Emobility and Stationary Storage Forward”. Available online: https://setis.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/set_plan_batteries_implementation_plan.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2020).

- Lee, C.; Xiaoding, W.; Jeffrey, W.K.; James, H. Measurement of the elastic properties and intrinsic strength of monolayer graphene. Science 2008, 321, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoller, M.D.; Park, S.; Zhu, Y.; An, J.; Ruoff, R.S. Graphene-based ultracapacitors. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 3498–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolotin, K.I.; Sikes, K.J.; Jiang, Z.; Klima, M.; Fudenberg, G.; Hone, J.; Kim, P.; Stormer, H. Ultrahigh electron mobility in suspended graphene. Solid State Commun. 2008, 146, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, K.Y. Electronic and Thermal Properties of Graphene; Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute: Basel, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou, D.G.; Kinloch, I.A.; Young, R.J. Mechanical properties of graphene and graphene-based nanocomposites. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2017, 90, 75–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandiatashbar, A.; Lee, G.-H.; An, S.J.; Lee, S.; Mathew, N.; Terrones, M.; Hayashi, T.; Picu, C.R.; Hone, J.; Koratkar, N. Effect of defects on the intrinsic strength and stiffness of graphene. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X. Fabrication and properties of carbon fibers. Materials 2009, 2, 2369–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Kumar, S. Recent progress in fabrication, structure, and properties of carbon fibers. Polym. Rev. 2012, 52, 234–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazali, N.; Salleh, W.; Izwanne, M.N.; Harun, Z.; Kadirgama, K. Precursor selection for carbon membrane fabrication: A review. J. Appl. Membr. Sci. Technol. 2018, 22, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.; Chang, D.; Xu, Z.; Gao, C. A review on graphene fibers: Expectations, advances, and prospects. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1902664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, K.K.; Bundaleska, N.; Abrashev, M.; Bundaleski, N.; Teodoro, O.; Fonseca, I.; de Ferro, A.M.; Silva, R.P.; Tatarova, E.; Montemor, M. Free-standing N-Graphene as conductive matrix for Ni(OH)2 based supercapacitive electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 334, 135592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Su, X.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Fang, Z.; Luo, X. Porous multishelled NiO hollow microspheres encapsulated within three-dimensional graphene as flexible free-standing electrodes for high-performance supercapacitors. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 16071–16079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mintmire, J.W.; Dunlap, B.I.; White, C.T. Are fullerene tubules metallic? Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992, 68, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.-A.; Ruan, W.; Chou, M. Electron-phonon interactions for optical-phonon modes in few-layer graphene: First-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 79, 115443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresselhaus, M.; Jorio, A.; Saito, R. Characterizing graphene, graphite, and carbon nanotubes by Raman spectroscopy. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2010, 1, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-C.; Walters, A.B.; Vannice, M.A. Measurement of electrical properties of a carbon black. Carbon 1995, 33, 1699–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott’s, I.E. Graphene: Exploring carbon flatland. Phys. Today 2007, 60, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Ando, T. Exotic electronic and transport properties of graphene. Phys. E Low Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2007, 40, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zheng, Q.-S.; Chen, G. Elementary building blocks of graphene-nanoribbon-based electronic devices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 223115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.C.; Guinea, F.; Peres, N.M.; Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K. The electronic properties of graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2009, 81, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelberger, E.; Dvali, G.; Gruzinov, A. Physical Review Letters, 98. Artic. Id 2007, 10402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Lee, S.; Dai, H. Chemically derived, ultrasmooth graphene nanoribbon semiconductors. Science 2008, 319, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.P.; Soares, O.; Fernandes, A.; Pereira, M.; Freire, C. Tuning the surface chemistry of graphene flakes: New strategies for selective oxidation. Rsc Adv. 2017, 7, 14290–14301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, T.; Berkesi, O.; Forgó, P.; Josepovits, K.; Sanakis, Y.; Petridis, D.; Dékány, I. Evolution of surface functional groups in a series of progressively oxidized graphite oxides. Chem. Mater. 2006, 18, 2740–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sun, H.; Ang, H.-M.; Tadé, M. Adsorptive remediation of environmental pollutants using novel graphene-based nanomaterials. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 226, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerf, A.; He, H.; Riedl, T.; Forster, M.; Klinowski, J. 13C and 1H MAS NMR studies of graphite oxide and its chemically modified derivatives. Solid State Ion. 1997, 101, 857–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, X.J.; Hiew, B.Y.Z.; Lai, K.C.; Lee, L.Y.; Gan, S.; Thangalazhy-Gopakumar, S.; Rigby, S. Review on graphene and its derivatives: Synthesis methods and potential industrial implementation. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2019, 98, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wang, H.; Qin, Z. Activated pyrene decorated graphene with enhanced performance for electrochemical energy storage. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 334, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosi, A.; Chua, C.K.; Bonanni, A.; Pumera, M. Electrochemistry of graphene and related materials. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 7150–7188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, R.S.; Coleman, K.S. Graphene synthesis: Relationship to applications. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K.; Morozov, S.V.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dubonos, S.V.; Grigorieva, I.V.; Firsov, A.A. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 2004, 306, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, Y.; Nicolosi, V.; Lotya, M.; Blighe, F.M.; Sun, Z.; De, S.; McGovern, I.; Holland, B.; Byrne, M.; Gun’Ko, Y.K. High-yield production of graphene by liquid-phase exfoliation of graphite. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2008, 3, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotya, M.; Hernandez, Y.; King, P.J.; Smith, R.J.; Nicolosi, V.; Karlsson, L.S.; Blighe, F.M.; De, S.; Wang, Z.; McGovern, I. Liquid phase production of graphene by exfoliation of graphite in surfactant/water solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 3611–3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotya, M.; King, P.J.; Khan, U.; De, S.; Coleman, J.N. High-concentration, surfactant-stabilized graphene dispersions. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 3155–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote, L.J.; Kim, J.; Tung, V.C.; Luo, J.; Kim, F.; Huang, J. Graphene oxide as surfactant sheets. Pure Appl. Chem. 2010, 83, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadukumpully, S.; Paul, J.; Valiyaveettil, S. Cationic surfactant mediated exfoliation of graphite into graphene flakes. Carbon 2009, 47, 3288–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.N. Liquid exfoliation of defect-free graphene. Accounts Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, R.; Kim, S.O. Surfactant mediated liquid phase exfoliation of graphene. Nano Converg. 2015, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yi, M.; Shen, Z. The effect of surfactants and their concentration on the liquid exfoliation of graphene. Rsc Adv. 2016, 6, 56705–56710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, B.C., XIII. On the atomic weight of graphite. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 1859, 149, 249–259. [Google Scholar]

- Staudenmaier, L. Verfahren zur darstellung der graphitsäure. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1898, 31, 1481–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, S.; Hummers, J.; Offeman, R.E. Preparation of graphitic oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958, 80, 1339. [Google Scholar]

- Poh, H.L.; Šaněk, F.; Ambrosi, A.; Zhao, G.; Sofer, Z.; Pumera, M. Graphenes prepared by Staudenmaier, Hofmann and Hummers methods with consequent thermal exfoliation exhibit very different electrochemical properties. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 3515–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yao, B.; Li, C.; Shi, G. An improved Hummers method for eco-friendly synthesis of graphene oxide. Carbon 2013, 64, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, M. Selling graphene by the ton. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009, 4, 612–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisticò, R.; Lavagna, L.; Versaci, D.; Ivanchenko, P.; Benzi, P. Chitosan and its char as fillers in cement-base composites: A case study. Bol. Soc. Esp. Cerám. Vidr. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoli, M.; Giorcelli, M.; Jagdale, P.; Rovere, M.; Tagliaferro, A. A review of non-soil biochar applications. Materials 2020, 13, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, S.K.; Sahoo, S.; Wang, N.; Huczko, A. Graphene research and their outputs: Status and prospect. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Devices 2020, 5, 10–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, G.; Lu, Y.; Wu, F.; Yang, C.; Zeng, F.; Wu, Q. Graphene oxide: The mechanisms of oxidation and exfoliation. J. Mater. Sci. 2012, 47, 4400–4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarascon, J.-M.; Armand, M. Issues and challenges facing rechargeable lithium batteries. In Materials for Sustainable Energy: A Collection of Peer-Reviewed Research and Review Articles from Nature Publishing Group; World Scientific: London, UK, 2011; pp. 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Boehm, H.; Setton, R.; Stumpp, E. Nomenclature and Terminology of Graphite Intercalation Compounds; Pergamon: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Scrosati, B. Lithium rocking chair batteries: An old concept? J. Electrochem. Soc. 1992, 139, 2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohzuku, T.; Iwakoshi, Y.; Sawai, K. Formation of lithium-graphite intercalation compounds in nonaqueous electrolytes and their application as a negative electrode for a lithium ion (shuttlecock) cell. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1993, 140, 2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YongJian, W.U.; RenHeng, T.; WenChao, L.I.; Ying, W.; Ling, H.; LiuZhang, O. A high-quality aqueous graphene conductive slurry applied in anode of lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 830, 154575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Yan, J.; Wu, H.; Shen, W.; Zhang, J.; Yu, C.; Li, L.; Hao, Q.; Gao, F.; Tian, Y.; et al. Multilayer graphene spheres generated from anthracite and semi-coke as anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Fuel Process. Technol. 2020, 198, 106241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, M.; Zhao, H.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Duan, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, J. Hierarchical porous carbon-graphene-based Lithium–Sulfur batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 318, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; De Hosson, J.T.M.; Pei, Y. Three-dimensional micron-porous graphene foams for lightweight current collectors of lithium-sulfur batteries. Carbon 2019, 144, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, B.; Zeng, H.; Huang, G.; Zhang, C.; Yuan, R.; Cao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yu, J. Porous graphene prepared from anthracite as high performance anode materials for lithium-ion battery applications. J. Alloy. Compd. 2019, 779, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.-Q.; Dong, X.-L.; Li, W.-C.; Hao, G.-P.; Yan, D.; Lu, A.-H. Millimeter-sized few-layer graphene sheets with aligned channels for fast lithium-ion charging kinetics. J. Energy Chem. 2020, 55, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Huang, J.; Ren, J.; Cao, L.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Lu, G.; Yu, A. A sandwich-like porous hard carbon/graphene hybrid derived from rapeseed shuck for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 818, 152849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Jia, K.; Liu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, K.; Zhang, B.; Wang, P. Facile synthesis 2D hierarchical structure of ultrahigh nitrogen-doped porous carbon graphene nanosheets as high-efficiency lithium-ion battery anodes. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 251, 123043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.; Hu, X. New strategy to prepare nitrogen self-doped graphene nanosheets by magnesiothermic reduction and its application in lithium ion batteries. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2019, 44, 24369–24376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadian, S.; Atashzar, S.M.; Gharibi, H.; Vafaee, M. Phosphorene and graphene flakes under the effect of external electric field as an anode material for high-performance lithium-ion batteries: A first-principles study. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2019, 165, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ershadi, M.; Javanbakht, M.; Mozaffari, S.A.; Brandell, D.; Lee, M.-T.; Zahiri, B. Facile stitching of graphene oxide nanosheets with ethylenediamine as three dimensional anode material for lithium-ion battery. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 818, 152912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Liu, X.; Xiao, M.; Hu, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, R.; Ke, X.; Ren, G.; Zhu, F. Reduced graphene oxide@nitrogen doped carbon with enhanced electrochemical performance in lithium ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 309, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, S.P.; Babu, B.; Prasannachandran, R.; Antony, R.; Shaijumon, M.M. Enhanced electrochemical properties of Mn3O4/graphene nanocomposite as efficient anode material for lithium ion batteries. J. Alloy. Compd. 2019, 780, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, F.; Wang, X.; Wang, G.; Wang, H.; Bai, J. Mn3O4 nanotubes encapsulated by porous graphene sheets with enhanced electrochemical properties for lithium/sodium-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 364, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, K.; Hong, M.; Yang, Y.; Hu, N.; Su, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y. Laser-induced MnO/Mn3O4/N-doped-graphene hybrid as binder-free anodes for lithium ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 385, 123720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Yue, W.; Chen, X. Fabrication of porous carbon-coated ZnO nanoparticles on electrochemical exfoliated graphene as an anode material for lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloy. Compd. 2019, 784, 800–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, N.; Yasin, G.; Li, A.; Chen, Y.; Saleem, H.M.; Liu, R.; Li, D.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, S.; Chen, X.; et al. Volumetric buffering of manganese dioxide nanotubes by employing ‘as is’ graphene oxide: An approach towards stable metal oxide anode material in lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 842, 155803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Miao, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, S.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y. Targeted interfacial anchoring and wrapping of Fe3O4 nanoparticles onto graphene by PPy-derived-carbon for stable lithium-ion battery anodes. Mater. Res. Bull. 2019, 111, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Wu, S. Pseudocapacitance behavior on Fe3O4-pillared SiOx microsphere wrapped by graphene as high performance anodes for lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 355, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Jiang, R.; Liu, H. Carbon layer encapsulated Fe3O4@Reduced graphene oxide lithium battery anodes with long cycle performance. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 12732–12739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yu, R.; Mao, G.; Yu, W.; Ding, Z.; Cao, Y.; Zheng, J.; Chu, D.; Tong, H. Unique FeP@C with polyhedral structure in-situ coated with reduced graphene oxide as an anode material for lithium ion batteries. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 841, 155670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Sun, L.; Wang, K.; Xu, S.; Zhang, J.; Guo, X.; Liu, X. Sandwiched N-carbon@Co9S8@Graphene nanosheets as high capacity anode for both half and full lithium-ion batteries. J. Energy Chem. 2020, 51, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, B.; Guo, J.; Lai, W.-H.; Wang, Y.-X.; Liu, M.; Liu, H.-K.; Wang, J.-Z.; Chou, S.-L.; Dou, S.-X. Layered mesoporous CoO/reduced graphene oxide with strong interfacial coupling as a high-performance anode for lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 843, 156050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.-L.; Liu, L.; Sun, Y.-H.; Yan, W.-J.; Wang, Z.-R.; Sun, Q. Ni-doped Ni3S2 nanoflake intertexture grown on graphene oxide as sheet-like anode for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 835, 155418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zheng, B.; Song, Z.; Shi, S.; Mao, H. Microwave-assisted synthesis of a novel CuC2O4∙xH2O/Graphene composite as anode material for lithium ion batteries. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 1018–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Lan, Q.; Yang, Z.; Lv, X.-J. Multiple phase N-doped TiO2 nanotubes/TiN/graphene nanocomposites for high rate lithium ion batteries at low temperature. J. Power Sources 2019, 423, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhu, J.; Li, B.; Li, C.; Wang, L.; Meng, W.; He, Z.; Dai, L. Synthesis and performance of a graphene decorated NaTi2(PO4)3/C anode for aqueous lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloy. Compd. 2019, 791, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Qiao, D.; Zhao, P.; He, Y.; Sun, W.; Yu, H.; Jiao, Z. Template-free synthesis of mesoporous succulents-like TiO2/graphene aerogel composites for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 300, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J. Uniformly distributed TiO2 nanorods on reduced graphene oxide composites as anode material for high rate lithium ion batteries. J. Alloy. Compd. 2019, 771, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.; Zhou, X.; Luo, J.; Ning, X. Ion assisted anchoring Sn nanoparticles on nitrogen-doped graphene as an anode for lithium ion batteries. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2019, 44, 24913–24921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Myung, Y.; Gu, M.G.; Kim, S.-K. Nanohybrid electrodes of porous hollow SnO2 and graphene aerogel for lithium ion battery anodes. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2019, 71, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-Z.; Brahma, S.; Weng, S.-C.; Chang, C.-C.; Huang, J.-L. Reduced graphene oxide (RGO)-SnOx (x = 0,1,2) nanocomposite as high performance anode material for lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 818, 152889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, S.; An, W.; Fu, J.; Guo, W.; Feng, X.; Li, X.; Gao, B.; Zhang, X.; Huo, K.; Chu, P.K. Hierarchical micro-flowers self-assembled from SnS monolayers and nitrogen-doped graphene lamellar nanosheets as advanced anode for lithium-ion battery. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 331, 135292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Hu, Z.; Mao, L.; Mao, J. Nano-silicon @ soft carbon embedded in graphene scaffold: High-performance 3D free-standing anode for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2020, 450, 227692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Liu, S.; Tao, L.; Tang, Y.; Dou, A.; Lv, J.; Liu, Y. Silicon@graphene composite prepared by spray–drying method as anode for lithium ion batteries. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2019, 844, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Sun, Z.; Yue, K.; Li, A.; Qian, L. CoO/ZnO nanoclusters immobilized on N-doped 3 D reduced graphene oxide for enhancing lithium storage capacity. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 836, 155443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

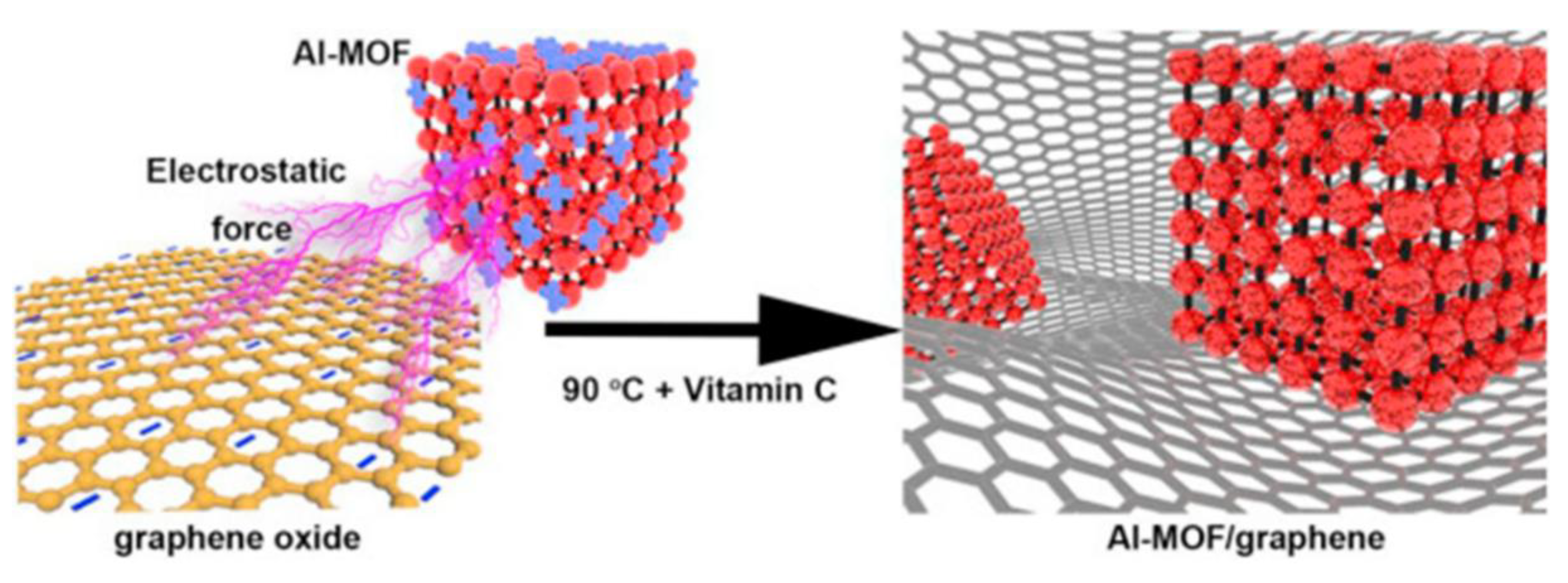

- Gao, C.; Wang, P.; Wang, Z.; Kær, S.K.; Zhang, Y.; Yue, Y. The disordering-enhanced performances of the Al-MOF/graphene composite anodes for lithium ion batteries. Nano Energy 2019, 65, 104032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Zhang, C.; Hao, R.; Hou, Y. Liquid-phase exfoliation, functionalization and applications of graphene. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 2118–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Z.; Wen-Long, W.; Xue-Dong, B. Preparing three-dimensional graphene architectures: Review of recent developments. Chin. Phys. B 2013, 22, 098105. [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan, N.; Thangavel, S.; Venugopal, G. A short review on preparation of graphene from waste and bioprecursors. Appl. Mater. Today 2017, 7, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Zhong, M.; Yu, C.; Zhang, J.; Ma, M.; Li, L.; Hao, Q.; Gao, F.; Tian, Y.; Huang, Y.; et al. Multilayer graphene sheets converted directly from anthracite in the presence of molten iron and their applications as anode for lithium ion batteries. Synth. Met. 2020, 263, 116364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, J.; Cheng, M.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Li, K.; Wang, J. N-doped porous carbon-graphene cables synthesized for self-standing cathode and anode hosts of Li–S batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 349, 136231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; He, Y.; Wang, L.; Ding, G.; Zhang, Z.-Q.; Lortz, R.W.; Sheng, P.; Wang, N. Electron localization in metal-decorated graphene. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 045431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petnikota, S.; Rotte, N.K.; Reddy, M.V.; Srikanth, V.V.S.S.; Chowdari, B.V.R. MgO-Decorated Few-Layered Graphene as an Anode for Li-Ion Batteries. Acs Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 2301–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Choi, W.Y.; Lee, S.; Kim, T.-S.; Lee, J.W. Graphene intercalated free-standing carbon paper coated with MnO2 for anode materials of lithium ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 348, 136310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhao, W.; Bi, H.; Tang, Y.; Huang, F. Tubular graphene-supported nanoparticulate manganese carbodiimide as a free-standing high-energy and high-rate anode for lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2020, 467, 228252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.-C.; Brahma, S.; Huang, P.-C.; Huang, Y.-C.; Lee, Y.-H.; Chang, C.-C.; Huang, J.-L. Enhanced capacity and significant rate capability of Mn3O4/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite as high performance anode material in lithium-ion batteries. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 505, 144629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Qiu, J.; Liu, M.; Ming, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, T. A surface multiple effect on the ZnO anode induced by graphene for a high energy lithium-ion full battery. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 824, 153945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fu, Y.; Chen, S.; Huang, Z.; Wang, L.; Song, Y. Porous Fe2O3/Fe3O4@Carbon octahedron arrayed on three-dimensional graphene foam for lithium-ion battery. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 171, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.W.; Wu, C.Y.; Huang, J.C.; Duh, J.G. Heterostructural modulation of in situ growth of iron oxide/holey graphene framework nanocomposites as excellent electrodes for advanced lithium-ion batteries. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 485, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Zhu, A. Graphene nanosheets loaded Fe3O4 nanoparticles as a promising anode material for lithium ion batteries. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 813, 152160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, H.; Xie, Z.; An, C.; Jiang, G.; Wang, Y. 3D graphene-encapsulated nearly monodisperse Fe3O4 nanoparticles as high-performance lithium-ion battery anodes. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 815, 152337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, B.; Samuel, E.; Kim, M.-W.; Kim, K.; Kim, T.-G.; Swihart, M.T.; Yoon, W.Y.; Yoon, S.S. Electrosprayed graphene films decorated with bimetallic (zinc-iron) oxide for lithium-ion battery anodes. J. Alloy. Compd. 2019, 782, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ma, X.; Shen, P.K. NiCo2S4 nanocores in-situ encapsulated in graphene sheets as anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 364, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Kong, F.; Tao, S.; Qian, B.; Jiang, X. Bimetal phosphide Ni1.4Co0.6P nanoparticle/carbon@ nitrogen-doped graphene network as high-performance anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 485, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lin, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, L.; Feng, Q.; Li, J.; Huang, Z. Three-dimensional hierarchical nanocomposites of NiSnO3/graphene encapsulated in carbon matrix as long-life anode for lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloy. Compd. 2019, 793, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefrançois Perreault, L.; Colò, F.; Meligrana, G.; Kim, K.; Fiorilli, S.; Bella, F.; Nair, J.R.; Vitale-Brovarone, C.; Florek, J.; Kleitz, F.; et al. Spray-dried mesoporous mixed Cu-Ni Oxide@ graphene nanocomposite microspheres for high power and durable Li-Ion battery anodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1802438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Fu, J.; Niu, M.; Quhe, R. MoO2 and graphene heterostructure as promising flexible anodes for lithium-ion batteries. Carbon 2019, 147, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, C.-Y.; Jin, X.; Kim, D.K.; Hwang, T.; Piao, Y. Hydrothermal synthesis of uniform tin oxide nanoparticles on reduced activated graphene oxide as anode material for lithium-ion batteries. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2019, 845, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.; Fielder, E.; Scrosati, B.; Wachtler, M.; Moreno, J.S. Structured silicon anodes for lithium battery applications. Electrochem. Solid State Lett. 2003, 6, A75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, Q.; Gong, Z.; Ostrikov, K. Graphene nanowalls conformally coated with amorphous/nanocrystalline Si as high-performance binder-free nanocomposite anode for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2019, 437, 226909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.-C.; Liu, W.-R. Carbon-coated Si particles binding with few-layered graphene via a liquid exfoliation process as potential anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 387, 125553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Lin, Z.; Ji, X.; Mu, Y.; Li, J.; Yu, J. Growth of flexible and porous surface layers of vertical graphene sheets for accommodating huge volume change of silicon in lithium-ion battery anodes. Mater. Today Energy 2020, 17, 100445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarascon, J.-M. Is lithium the new gold? Nat. Chem. 2010, 2, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, C.; Miranda, P.H.; Perrin, M.; Poggi, P. Assessment of world lithium resources and consequences of their geographic distribution on the expected development of the electric vehicle industry. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 1735–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.A.; Rucci, A.; Brandell, D.; Frayret, C.; Gaberscek, M.; Jankowski, P.; Johansson, P. Boosting Rechargeable Batteries R&D by Multiscale Modeling: Myth or Reality? Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 4569–4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.; Zhao, D.; He, H.; Cao, W.; Dong, G. A noise-tolerant model parameterization method for lithium-ion battery management system. Appl. Energy 2020, 268, 114932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Zhao, J.; Ji, D.; Tseng, K.J. A multi-timescale estimator for battery state of charge and capacity dual estimation based on an online identified model. Appl. Energy 2017, 204, 1264–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponrouch, A.; Palacín, M.R. Post-Li batteries: Promises and challenges. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2019, 377, 20180297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitta, N.; Wu, F.; Lee, J.T.; Yushin, G. Li-ion battery materials: Present and future. Mater. Today 2015, 18, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, C. Sodium and Sodium-Ion Batteries: 50 Years of Research. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1703137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramudita, J.C.; Sehrawat, D.; Goonetilleke, D.; Sharma, N. An initial review of the status of electrode materials for potassium-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1602911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-de Dompablo, M.E.; Ponrouch, A.; Johansson, P.; Palacín, M.R. Achievements, challenges, and prospects of calcium batteries. Chem. Rev. 2019, 120, 6331–6357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohtadi, R.; Mizuno, F. Magnesium batteries: Current state of the art, issues and future perspectives. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2014, 5, 1291–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.W.; Aurbach, D. Promise and reality of post-lithium-ion batteries with high energy densities. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrota, A.S.; Pašti, I.A.; Mentus, S.V.; Johansson, B.; Skorodumova, N.V. Altering the reactivity of pristine, N- and P-doped graphene by strain engineering: A DFT view on energy related aspects. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 514, 145937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhu, D.; Liang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, W.; Ren, X.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Gao, Y.; Wen, W.; et al. Facile renewable synthesis of nitrogen/oxygen co-doped graphene-like carbon nanocages as general lithium-ion and potassium-ion batteries anode. Carbon 2020, 167, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Hu, X.; Zeng, T.; Shang, B.; Mao, M.; Jiao, X.; Xi, G. FeSb2S4 anchored on amine-modified graphene towards high-performance anode material for sodium ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 385, 123857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Xing, Z.; Zheng, G.; Gao, X.; Hong, H.; Ju, Z.; Zhuang, Q. MoS2/N-doped graphene aerogles composite anode for high performance sodium/potassium ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 339, 135932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Lin, X.; Wang, D.; Yuan, R.; Zhang, S.; Chen, X.; Bulusheva, L.G.; Okotrub, A.V.; Song, H. Modulating the defects of graphene blocks by ball-milling for ultrahigh gravimetric and volumetric performance and fast sodium storage. Energy Storage Mater. 2020, 30, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, C.; Shi, J.; Zhao, Y. Highly monodispersed graphene/SnO2 hybrid nanosheets as bifunctional anode materials of Li-ion and Na-ion batteries. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 821, 153506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, B.; Yang, Z.; Cai, W.; Sui, J.; Cao, G.; Wang, H.-E. Dual interface coupled molybdenum diselenide for high-performance sodium ion batteries and capacitors. J. Power Sources 2020, 446, 227298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashairya, L.; Saha, P. Antimony Sulphide Nanorods Decorated onto Reduced Graphene Oxide Based Anodes for Sodium-Ion Battery. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 21, 1899–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Zhang, C.; Kong, D.; He, X.; Xiao, J.; Chen, F.; Tao, Y.; Wan, Y.; Yang, Q.-H. Flowable sulfur template induced fully interconnected pore structures in graphene artefacts towards high volumetric potassium storage. Nano Energy 2020, 72, 104729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaletdinov, R.D.; Pershin, Y.V. Ultrafast lithium diffusion in bilayer buckled graphene: A comparative study of Li and Na. Scr. Mater. 2020, 178, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Sun, J.; Miao, L.; Yan, Z.; Chen, J. Layered H0.68Ti1.83O4/reduced graphene oxide nanosheets as a novel cathode for rechargeable magnesium batteries. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 14578–14581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latha, M.; Biswas, S.; Rani, J.V. Application of WS 2-G composite as cathode for rechargeable magnesium batteries. Ionics 2020, 26, 3395–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niaei, A.H.F.; Hussain, T.; Hankel, M.; Searles, D.J. Hydrogenated defective graphene as an anode material for sodium and calcium ion batteries: A density functional theory study. Carbon 2018, 136, 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Share, K.; Cohn, A.P.; Carter, R.; Rogers, B.; Pint, C.L. Role of nitrogen-doped graphene for improved high-capacity potassium ion battery anodes. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 9738–9744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Electrode Material | Capacity [mAhg−1] | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Graphene watery slurry | 1279 | [76] |

| Multilayers graphene from anthracite | 404 | [77] |

| Hierarchical graphene a | 1178 | [78] |

| Graphene foam from metal template approach a | 844 | [79] |

| Graphene foam from anthracite | 770 | [80] |

| Channeled few layer graphene | 142 | [81] |

| Hard carbon/graphene hybrid | 623 | [82] |

| Nitrogen doped graphene | 907 | [83] |

| Nitrogen doped graphene through magnesiothermic reduction of melamine | 1753 | [84] |

| Phosphorene-graphene hybrid | 974 | [85] |

| 3D-structured nitrogen doped GO | 830 | [86] |

| Nitrogen doped rGO | 409 | [87] |

| Mn3O4 doped graphene | 474 | [88] |

| Mn3O4 nanotubes doped graphene | 770 | [89] |

| MnO/Mn3O4/nitrogen doped graphene hybrid | 365 | [90] |

| Graphene tailored with carbon coated ZnO nanoparticles | 736 | [91] |

| GO tailored with MnO2 nanotubes | 1290 | [92] |

| Graphene tailored with Fe3O4 nanoparticles | 721 | [93] |

| Graphene foam tailored with porous Fe2O3/Fe3O4 | 1210 | [34] |

| Fe3O4-pillared onto SiOx microsphere and wrapped by graphene | 833 | [94] |

| Carbon encapsulated Fe3O4 doped rGO | 844 | [95] |

| Iron phosphide/rGO | 950 | [96] |

| Cobalt nanoparticles tailored nitrogen doped graphene | 1009 | [97] |

| CoO tailored rGO | 1167 | [98] |

| Ni/Ni3S2 doped GO | 742 | [99] |

| Copper oxalate/graphene composite | 1043 | [100] |

| TiO2/TiN/graphene | 221 | [101] |

| Graphene decorated with NaTi2(PO4)3 b | 108 | [102] |

| rGO tailored with TiO2 nanorods | 354 | [103] |

| Sn nanoparticles supported onto graphene | 584 | [104] |

| SnO2/graphene aerogel | 620 | [105] |

| rGO tailored with SnOx | 833 | [106] |

| Graphene tailored with SnS | 790 | [107] |

| Nano silicon supported onto soft carbon embedded in graphene | 2600 | [108] |

| Silicon/graphene hybrid | 1298 | [109] |

| Graphene tailored with Co/ZnO | 1494 | [110] |

| Al-MOF/graphene composite | 400 | [111] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lavagna, L.; Meligrana, G.; Gerbaldi, C.; Tagliaferro, A.; Bartoli, M. Graphene and Lithium-Based Battery Electrodes: A Review of Recent Literature. Energies 2020, 13, 4867. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13184867

Lavagna L, Meligrana G, Gerbaldi C, Tagliaferro A, Bartoli M. Graphene and Lithium-Based Battery Electrodes: A Review of Recent Literature. Energies. 2020; 13(18):4867. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13184867

Chicago/Turabian StyleLavagna, Luca, Giuseppina Meligrana, Claudio Gerbaldi, Alberto Tagliaferro, and Mattia Bartoli. 2020. "Graphene and Lithium-Based Battery Electrodes: A Review of Recent Literature" Energies 13, no. 18: 4867. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13184867

APA StyleLavagna, L., Meligrana, G., Gerbaldi, C., Tagliaferro, A., & Bartoli, M. (2020). Graphene and Lithium-Based Battery Electrodes: A Review of Recent Literature. Energies, 13(18), 4867. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13184867