Moisture-Safe Cold Attics in Humid Climates of Europe and North America

Abstract

1. Introduction

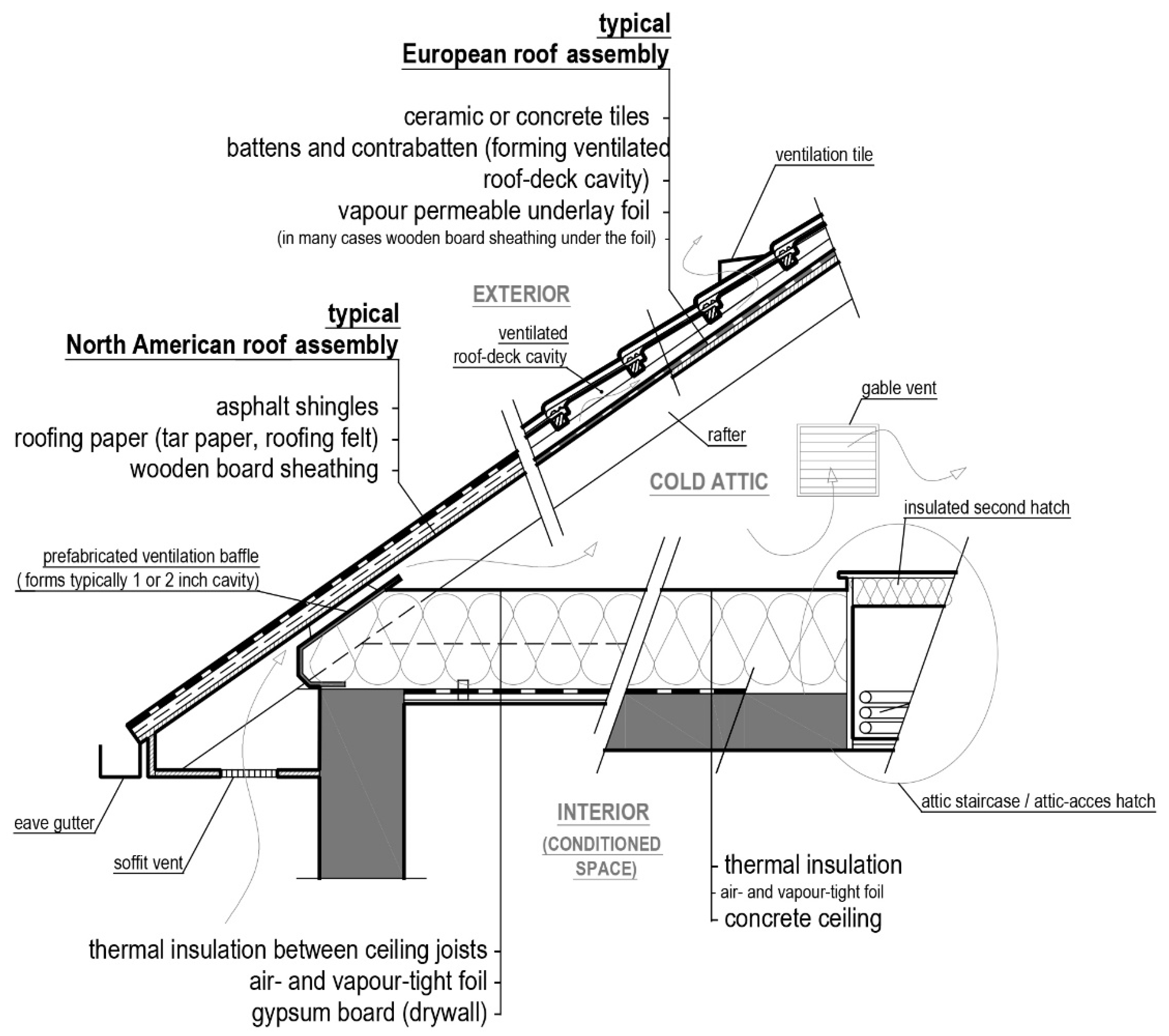

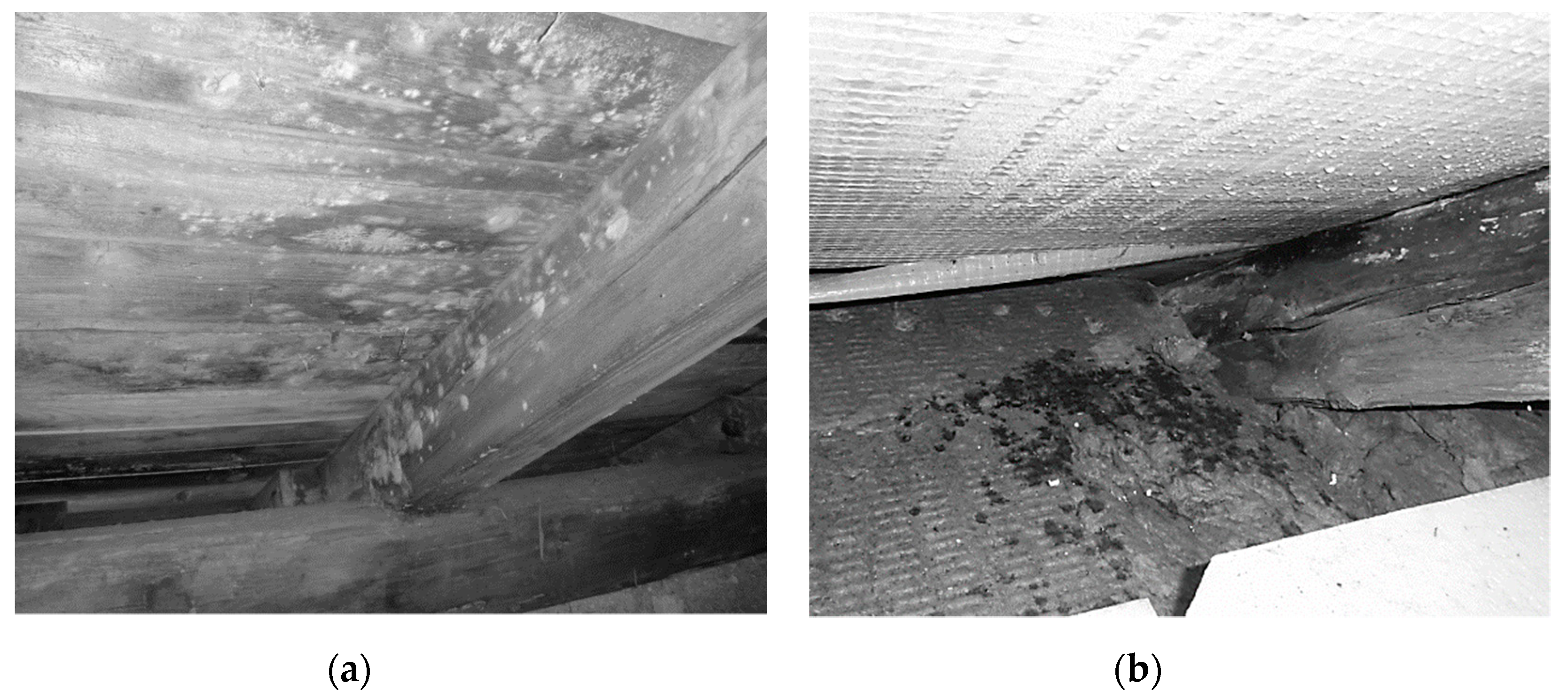

1.1. Background

1.2. Goal of this Paper

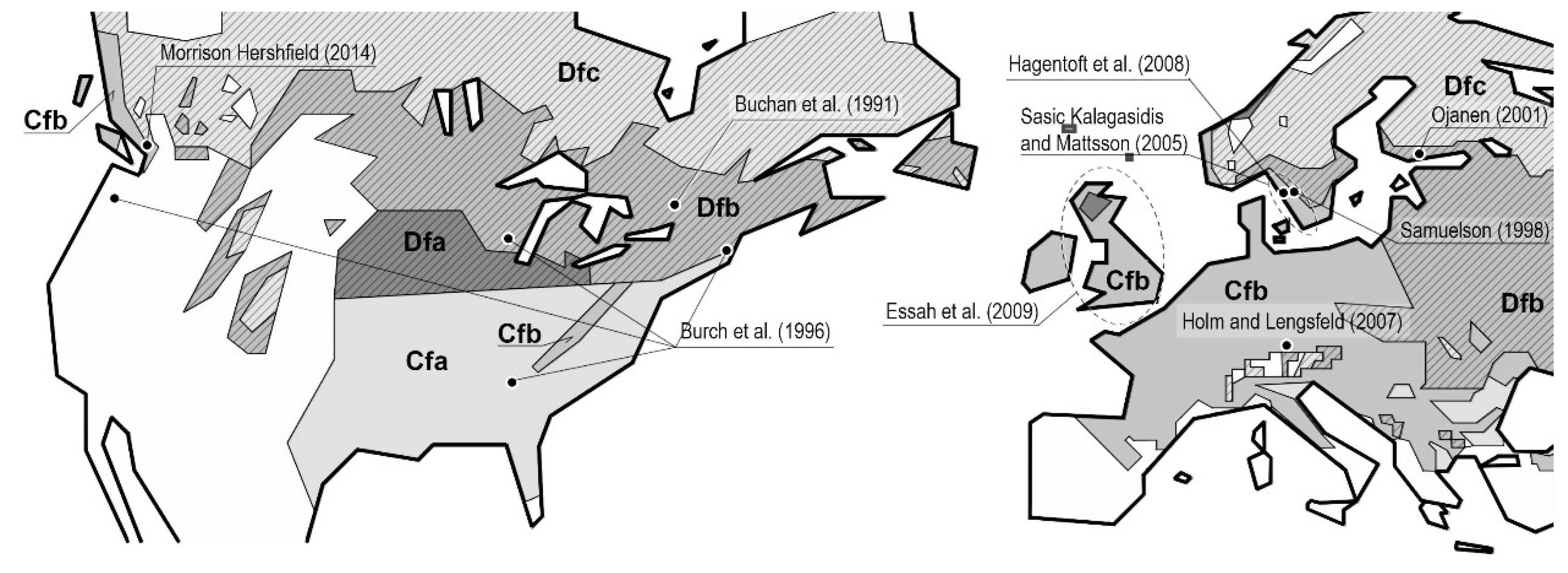

1.3. Target Region

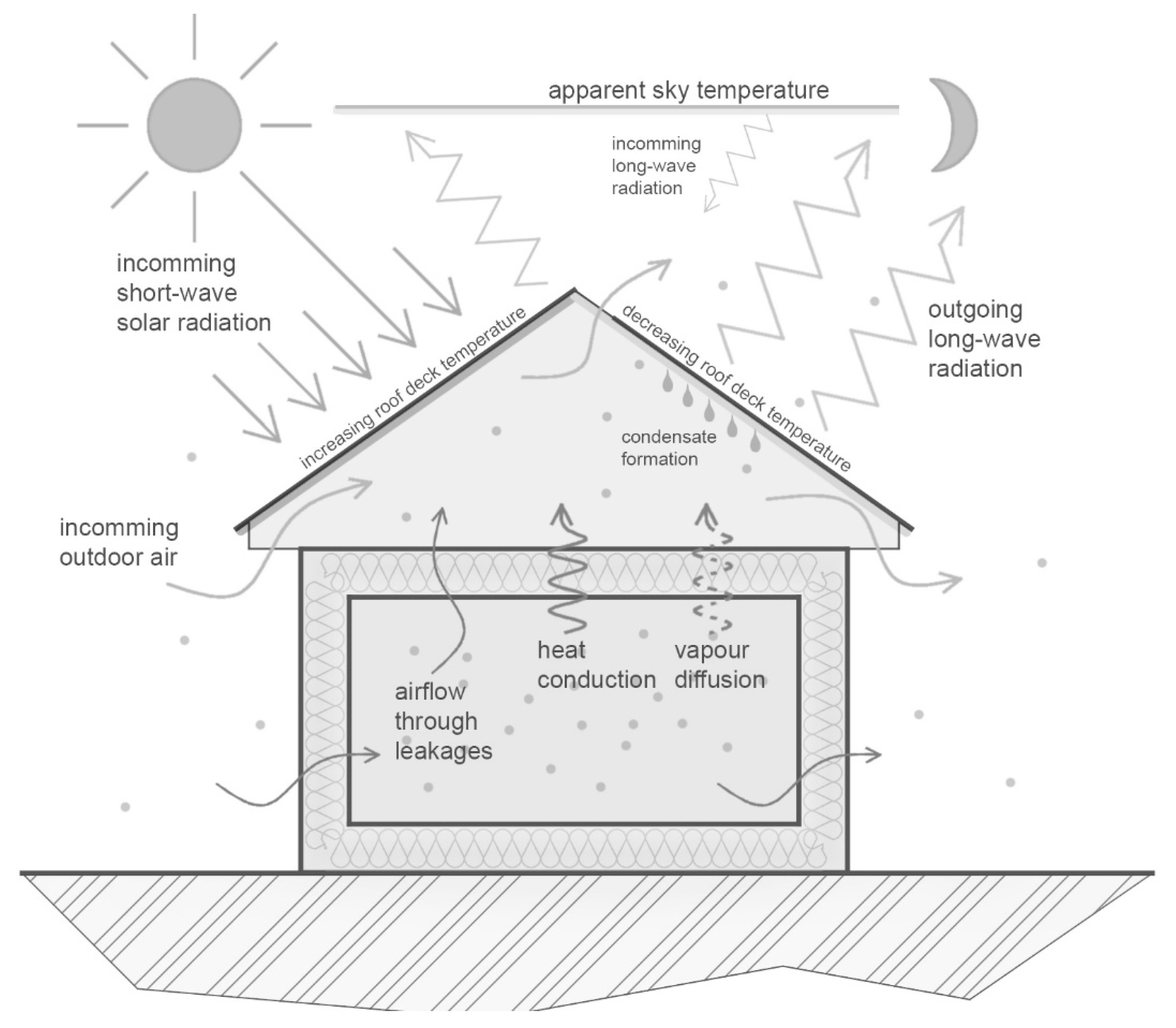

1.4. Causes of Problems and General Measures

2. Methods

2.1. Selection of Studies and Attic Designs

2.2. Table of Attic Designs

2.3. Comparative Parameters

2.3.1. Real Interior–Attic Air Change Rate

2.3.2. Ceiling Equivalent Air Layer Thickness

2.3.3. Ceiling Thermal Transmittance

2.3.4. Roof-Deck Equivalent Air Layer Thickness

2.3.5. Exterior–Attic Air Change Rate (Attic Ventilation Rate)

2.3.6. Presence of a Ventilated Roof-Deck Cavity

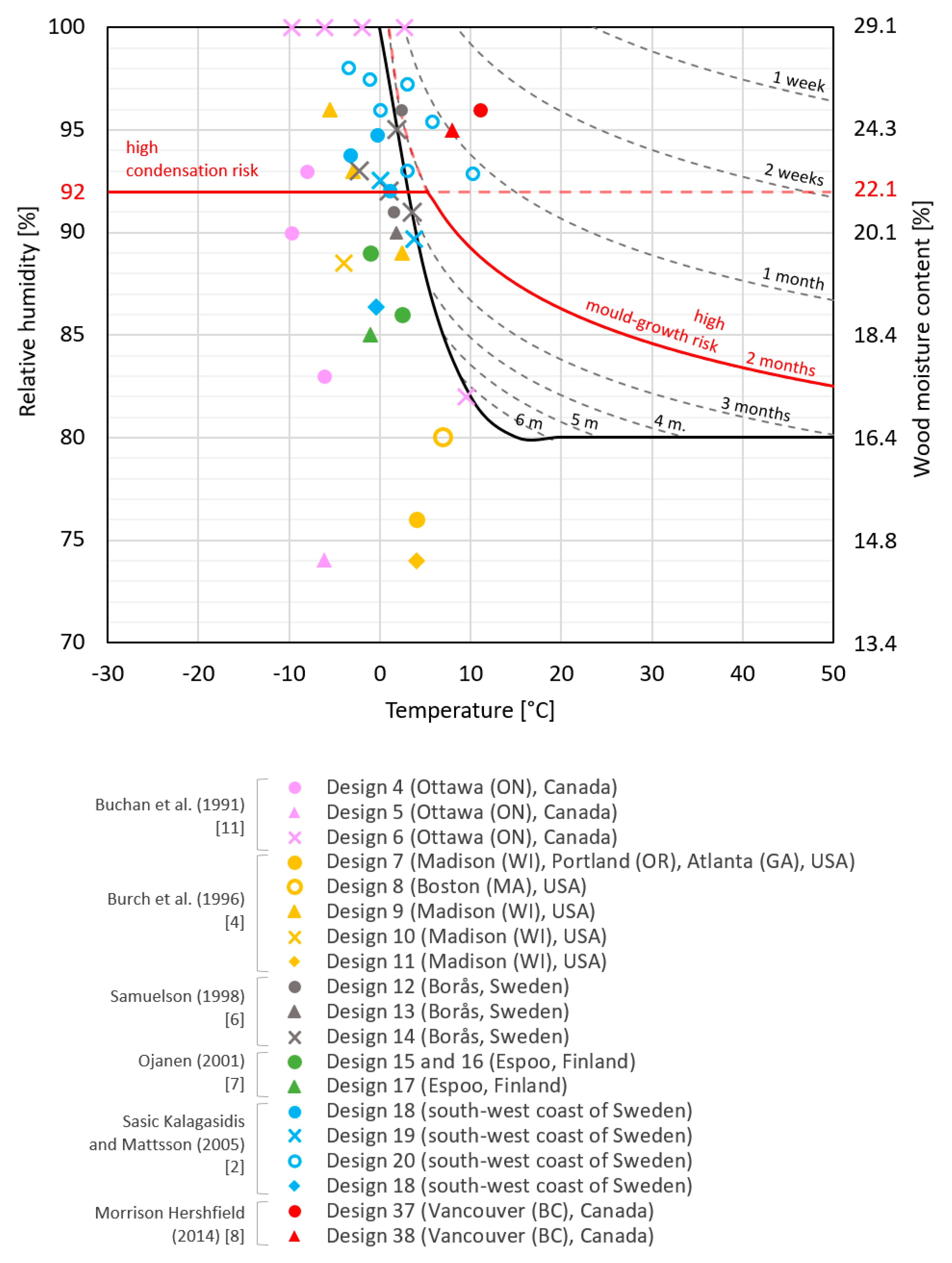

2.4. Moisture-Risk Evaluation

2.5. Groups of Similar Attic Designs

2.5.1. Real Interior–Attic Air Change Rate

2.5.2. Roof-Deck Equivalent Air Layer Thickness

2.5.3. Exterior–Attic Air Change Rate

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Richter, J. Cold Attics in Humid Cold and Temperate Climate. Ph.D. Thesis, Czech Technical University in Prague, Prague, Czech Republic, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kalagasidis, A.S.; Mattsson, B. Modelling of moisture conditions in a cold Attic space. In Proceedings of the 26th AIVC Conference, Brussels, Belgium, 21–23 September 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley, F.B.; Algren, A.B.; Lund, C.E. Condensation of Moisture and its Relation to Building Construction and Operation. In Bulletin of the University of Minnesota; University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1941; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11299/124254 (accessed on 27 July 2020).

- Burch, D.M.; Tsongas, G.A.; Walton, G.N. Mathematical Analysis of Practices to Control Moisture in the Roof Cavities of Manufactured Homes, NISTIR 5880; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 1996.

- Holm, A.; Lengsfeld, K. Hygrothermal Performance of Ventilated Cold Roofs—An Experimental Study. In Proceedings of the 11th Canadian Conference on Building Science and Technology, Banff, AB, Canada, 21–23 March 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson, I. Hygrothermal performance of attics. Therm. Envel. Build. Sci. 1998, 22, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojanen, T. Thermal and moisture performance of a sealed cold-roof system with a vapor-permeable underlay. In Proceedings of the Exterior Envelopes of Whole Buildings VIII, Clearwater Beach, FL, USA, 2–7 December 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hershfield, M. Attic Ventilation and Moisture Research Study—Final Report; Homeowner Protection Office: Burnaby, BC, Canada, June 2014. Available online: https://www.bchousing.org/research-centre/library/building-science-reports/attic-ventilation-moisture-research-study (accessed on 27 July 2020).

- Hagentoft, C.-E.; Sasic Kalagasidis, A.; Nilsson, S.F.; Thorin, M. Mould growth control in cold attics through adaptive ventilation. In Proceedings of the 8th Nordic Symposium on Building Physics, Copenhagen, Denmark, 16–19 June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Essah, E.; Sanders, C.; Baker, P.; Sasic Kalagasidis, A. Condensation and moisture transport in cold roofs: Effects of roof underlay. Build. Res. Inform. 2009, 37, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan Lawton Parent Ltd. Survey of Moisture Levels in Attics (No. BLP File No. 2497); Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation Research Division: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hagentoft, C.-E.; Sasic Kalagasidis, A. Mould Growth Control in Cold Attics through Adaptive Ventilation: Validation by Field Measurements. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Performance of the Exterior Envelopes of Whole Buildings, Clearwater Beach, FL, USA, 1–5 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Essah, E. Domestic cold pitched roofs in the UK—Effects of using different roof insulation materials. Int. J. Vent. 2012, 11, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagentoft, C.-E.; Sasic Kalagasidis, A. Moisture safe cold attics—Assessment based on risk analyses of performance and cost. In Proceedings of the 10th Nordic Symposium on Building Physics, Lund, Sweden, 15–19 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bjarløv, S.P.; Johnston, C.J.; Hansen, M.H. Hygrothermal conditions in cold, north facing attic spaces under the eaves with vapour-open roofing underlay in a cool, temperate climate. Build. Environ. 2016, 95, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.; Moeller, E.B. Hygrothermal performance of cold ventilated attics above different horizontal ceiling constructions—Field survey. Build. Environ. 2019, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uvsløkk, S. Moisture and temperature conditions in cold lofts and risk of mould growth. In Proceedings of the 7th Symposium on Building Physics in the Nordic Countries, Reykjavik, Iceland, 13–15 June 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, A.; Morelli, M. Measured temperature and moisture conditions in the roof attic of a one-and-a-half story house. Energy Procedia 2017, 132, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfvidsson, J.; Harderup, L.-E. Moisture Safety in Attics Ventilated by Outdoor Air. In Proceedings of the 7th Symposium on Building Physics in Nordic Countries, Reykjavik, Iceland, 13–15 June 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, P.; Bok, G.; Ekstrand-Tobin, A. Mould Growth in Attics and Crawlspaces. In Proceedings of the 9th Nordic Symposium on Building Physics, Tampere, Finland, 29 May–2 June 2011; pp. 891–898. [Google Scholar]

- Desjarlais, A.; Miller, W.; Railkar, S.; Chich, A. Energy and Moisture Performance of Attic Assemblies. In Proceedings of the RCI Building Envelope Technology Symposium, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 22–23 October 2012; pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Nik, M.V.; Sasic Kalagasidis, A.; Kjellström, E. Assessment of hygrothermal performance and mould growth risk in ventilated attics in respect to possible climate changes in Sweden. Build. Environ. 2012, 55, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harderup, L.-E.; Arfvidsson, J. Moisture Safety in Cold Attics with Thick Thermal Insulation. Archit. Eng. 2013, 19, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahl, D.; Shaffer, M. Moisture Risk in Unvented Attics Due to Air Leakage Paths; U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2014.

- Mundt-Petersen, S.O.; Harderup, L.-E. Predicting hygrothermal performance in cold roofs using a 1D transient heat and moisture calculation tool. Build. Environ. 2015, 90, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurkinen, K. Case Study of a Cold Attic in a Pitched Roof with Minimal Ventilation. Energy Procedia 2017, 132, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Wang, R.; Baril, D. Field measurements of hygrothermal performance of attics in extreme cold climates. Build. Environ. 2018, 134, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest, T.W.; Walker, I.S. Attic Ventilation and Moisture. In Final Report Prepared for Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation; Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1993; Available online: ftp://ftp.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/chic-ccdh/Research_Reports-Rapports_de_recherche/Older11/Ca1%20MH%2093A78%20v.%201_w.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- Finch, G.; LePage, R.; Ricketts, L.; Higgins, J.; Dell, M. The Problems with and Solutions for Ventilated Attics. In Proceedings of the 30th RCI International Convention and Trade Show, RCI Inc., San Antonio, TX, USA, 20–25 March 2015; pp. 203–216. Available online: http://rdh.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/The-Problems-with-and-Solutions-or-Ventilated-Attics-GFINCH.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- Hens, H. Applied Building Physics: Boundary Conditions, Building Performance and Material Properties, 1st ed.; Ernst & Sohn: Berlin, Germany, 2010; ISBN 9783433029626. [Google Scholar]

- Stamisol. Available online: https://www.stamisol.com/en/about-stamisol/history.html (accessed on 18 January 2020).

- Janssens, A. Reliable Control of Interstitial Condensation in Light-Weight Roof Systems: Calculation and Assessment Methods. Ph.D. Thesis, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Solař, J. Problematika Nadměrné Vlhkosti U Střešních Plášťů Šikmých A Strmých Střech, TZB-Info. 2012. Available online: https://stavba.tzb-info.cz/strechy/8852-problematika-nadmerne-vlhkosti-u-stresnich-plastu-sikmych-a-strmych-strech (accessed on 30 April 2020). (In Czech).

- Gullbrekken, L.; Kvande, T.; Jelle, B.P.; Time, B. Norwegian Pitched Roof Defects. Buildings 2016, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagentoft, C.-E.; Sasic Kalagasidis, A. Drying potential of cold attic using natural and controlled ventilation in different Swedish climates. Procedia Eng. 2016, 146, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. World map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorol. Z. 2006, 15, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.E.; Zimmermann, N.E.; McVicar, T.R.; Vergopolan, N.; Berg, A.; Wood, E.F. Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, W.B.; TenWolde, A.A. Venting of Attics and Cathedral Ceilings. ASHRAE J. 2002, 44, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lstiburek, J. Understanding Attic Ventilation. Build. Sci. Dig. 2006, 102, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, I.S.; Forest, T.W. Field Measurements of Ventilation Rates in Attics. Build. Environ. 1995, 30, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, J. Risk of Condensation in Unheated Attic Spaces. Master’s Thesis, Czech Technical University in Prague, Prague, Czech Republic, 2013. (In Czech). [Google Scholar]

- Less, B.; Walker, I.S.; Levinson, R. A Literature Review of Sealed and Insulated Attics—Thermal, Moisture and Energy Performance; LBNL-1006493; Lawrence Berkeley National Lab: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adan, O.C.G.; Samson, R.A. Fundamentals of Mould Growth in Indoor Environments and Strategies for Healthy Living; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2011; ISBN 978-90-8686-135-4. e-ISBN 978-90-8686-722-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rychtera, M.; Němcová-Machová, B.; Genovová, E. Atmospheric Microbial Corrosion of Technical Materials and Its Prediction; Academia. Edice: Prague, Czech Republic, 1974. (In Czech) [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, P. Critical Moisture Conditions for Mould Growth on Building Materials. Ph.D. Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dix, N.J.; Webster, J. Fungal Ecology; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1995; p. 549, ISBN 978-94-010-4299-4 (print) 978-94-011-0693-1 (online). [Google Scholar]

- Shigo, A.L. Biological of decay and wood quality. In Biological Transformation of Wood by Microorganisms; Liese, W., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 1975; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sedlbauer, K. Prediction of Mold Fungus Formation on the Surface of and Inside Building Components. Ph.D. Thesis, Stuttgart University, Stuttgart, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Platt, S.D.; Martin, C.J.; Hunt, S.M.; Lewis, C.W. Damp housing, mould growth, and symptomatic health state. BMJ 1989, 298, 1673–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piecková, E.; Jesenská, Z. Microscopic fungi in dwellings and their health implications. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 1999, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Tywoniak, J.; Svoboda, Z.; Matuška, T. ČSN 730540-2—Thermal Protection of Buildings—Section 2: Requirements; Office for Technical Standardization, Metrology and Testing: Prague, Czech Republic, 2011. (In Czech) [Google Scholar]

- Rowley, F.B.; Algren, A.B.; Lund, C.E. Condensation of Moisture and its Relation to Building Construction and Operation. ASHRAE Trans. 1939, 44, 1115. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, I.S.; Less, B.D. Measured Moisture Performance of Sealed and Insulated Attics with Permeable Insulation in California homes. In Proceedings of the Thermal Performance of the Exterior Envelopes of Buildings XIV, Clearwater Beach, FL, USA, 9–12 December 2019; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019; pp. 774–782. [Google Scholar]

- Vereecken, E.; Roels, S. Review of mould prediction models and their influence on mould risk evaluation. Build. Environ. 2012, 51, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hukka, A.; Viitanen, H.A. A mathematical model for mould growth on wooden material. Wood Sci. Technol. 1999, 33, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viitanen, H.A.; Ojanen, T. Improved model to predict mold growth in building materials. In Proceeding of the Thermal Performance of the Exterior Envelopes of Whole Buildings, ASHRAE THERM X, Clearwater, FL, USA, 4–8 December 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vereecken, E.; Vanoirbeek, K.; Roels, S. Towards a more thoughtful use of mould prediction models: A critical view on experimental mould growth research. J. Build. Phys. 2015, 39, 102–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, S.V.; Gatland, S.D., II; Ueno, K.; Schumacher, C.J. Analysis of Improved Criteria for Mold Growth in ASHRAE Standard 160 by Comparison with Field Observations. In Advances in Hygrothermal Performance of Building Envelopes: Materials, Systems and Simulations; Mukhopadhyaya, P., Fisler, D., Eds.; ASTM STP1599; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 160-2009. Criteria for Moisture-Control Design Analysis in Buildings; American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2009; Available online: https://www.techstreet.com/standards/ashrae-160-2016?product_id=1939166 (accessed on 27 July 2020).

- Ross, R.J. Wood Handbook: Wood as An Engineering Material, General Technical Report FPL–GTR–190; Forest Products Laboratory, USDA: Madison, WI, USA, 2010.

- Climate-Data. Available online: https://en.climate-data.org/info/sources/ (accessed on 9 January 2020).

- Passive House Institute. Available online: https://passiv.de/en/02_informations/02_passive-house-requirements/02_passive-house-requirements.htm (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Walker, I.S.; Wilson, D.J. Field Validation of Algebraic Equations for Stack and Wind Driven Air Infiltration Calculations. HVAC R Res. J. 1998, 4, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Air Barrier Association. Available online: https://www.naba.ca/air_barriers/materials.php (accessed on 22 January 2020).

| Main Climate | Precipitation | Temperature | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| warm temperate | fully humid | hot summer | Cfa |

| warm temperate | fully humid | warm summer | Cfb |

| snow | fully humid | hot summer | Dfa |

| snow | fully humid | warm summer | Dfb |

| snow | fully humid | cool summer | Dfc |

| Class | nint–att (h−1) |

|---|---|

| extremely low leakage | 0.00–0.04 |

| low leakage | 0.04–0.10 |

| medium leakage | 0.10–0.18 |

| high leakage | >0.18 |

| Class | sd,r.deck (m) |

|---|---|

| vap.-permeable | 0.02–0.3 |

| vap.-medium-permeable | 0.6–2.6 |

| vap.-tight | ≥10 |

| Class | next–att (h−1) |

|---|---|

| unventilated attic | 0.0–0.3 |

| slightly ventilated attic | 0.6–3.3 |

| ventilated attic | ≥4 |

| Design No. | Study | Study Type | Attic Location and Period of Test (If Provided) | Köppen–Geiger Climate Class. According to [33] | Interior Conditions | Attic Design Parameters | Moisture-Related Consequences | Moisture-Risk Level | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nint–att (h−1) (Qint–att) (l/s/m2) | sd,ceil (m) | Uceil (W/m2/K) | sd_r.deck (m) | Presence of Roof-Deck Cavity. Y—yes, N – no | next–att (h−1) {Ventilation Ratio} | ||||||||

| 31 | Essah et al. (2009) [10] | C | United Kingdom | Cfb | 20–25 °C 40–70 %RH (according to high occupancy in the mentioned standard) n50 = 5 h−1 (1 year sim.) | 0 | ca. 0.5 #e | ca. 0.15 | 0.02 | Y | estimated ca 0.1 no intentional openings (the roof leakage flow rate is several orders of magnitude lower than intentional ventilation) | 2 kg/year of condensate on the attic underlay (ca. 26 g/m2/year) | (0) |

| 13 | Samuelson (1998) [6] | E | Borås, Sweden (1994–1995) | Cfb | ca. 17–24 °C 31–55 %RH (1 year meas.) | 0 | ca. 10 | 0.077 | ca. 1.2 | Y | ca. 0.2 #a unventilated | max monthly avg. RH = 90 % (1.8 °C) (December) | (0) |

| 14 | Samuelson (1998) [6] | E | Borås, Sweden (1994–1995) | Cfb | ca. 17–24 °C 31–55 %RH (1 year meas.) | 0 | ca. 10 | 0.077 | ca. 1.2 | Y | ca. 32 *** natural eave ventilation {ca. 1:84} | max monthly avg. RH = 95 % (1.9 °C) (December) | (2) |

| 21 | Sasic Kalagasidis and Mattsson (2005) [2] | C | South-west coastal area of Sweden (wind exposure—city) | Cfb | 22 °C 40–70 %RH (1 year sim.) exhaust—supply vent. (out 120 m3/h — in 90%) | 0 | ca. 11 | ca. 0.077 | ca. 0.6 | Y | mean 0.1 (unventilated design) | Mould index = 0.001 #,#d (four year simulation) | (0) |

| 30 | Essah et al. (2009) [10] | C | United Kingdom | Cfb | 20–25 °C 40–70 %RH (according to high occupancy in the mentioned standard) n50 = 5 h−1 (1 year sim.) | 0 | ca. 0.5 #e | ca. 0.15 | moisture dependent 0.6–4.6 | Y | estimated ca 0.1 no intentional openings (the roof leakage flow rate is several orders of magnitude lower than intentional ventilation) | 66 kg/year of condensate on the attic underlay (ca. 870 g/m2/year) | (2) |

| 12 | Samuelson (1998) [6] | E | Borås, Sweden (1994 – 1995) | Cfb | ca. 17–24 °C 31–55 %RH (1 year meas.) | 0 | ca. 10 | 0.077 | ca. 10 | Y | mechanical 2 h−1 | max monthly avg. RH = 96 % (2.4 °C) (December) | (2) |

| 24 | Hagentoft et al. (2008) [9] | C | Gothenburg region, Sweden | Cfb | 30–60 %RH; — balanced ventilation (1 year sim.) | 0 | ca. 10 | ca. 0.10 | ca. 12 | Y | ca. 22 *** (130 h−1 at 50 Pa p. dif.) | Mould index = 1.35 # (total of 11 weeks in 90–100 %RH and 0–5 °C; 5 weeks in 80–90 %RH and 5–15 °C; 3 weeks in 70–80 %RH and above 15 °C) | (1) |

| 29 | Essah et al. (2009) [10] | C | United Kingdom | Cfb | 20–25 °C 40–70 %RH (according to high occupancy in the mentioned standard) n50 = 5 h−1 (1 year sim.) | 0 | ca. 0.5 #e | ca. 0.15 | 40 | Y | estimated ca 0.1 no intentional openings (roof leakage flow rate is several orders of magnitude lower than intentional ventilation) | 83 kg/year of condensate on the attic underlay (ca. 1100 g/m2/year) | (3) |

| 28 | Essah et al. (2009) [10] | C | United Kingdom | Cfb | 20–25 °C 40–70 %RH (according to high occupancy in the mentioned standard) n50 = 5 h−1 (1 year sim.) | 0 | ca. 0.5 #e | ca. 0.15 | 40 | Y | ca. 4.6 #k {ca. 1:170} (28 h−1 at 50 Pa p.dif.) (20 mm openings along the eaves) | 0 kg/year of condensate on the attic underlay | (0) |

| 11 | Burch et al. (1996) [4] | C | Madison (WI), USA | Dfb | 20–24 °C ca. 20–60% (1 year sim.) | 0 | ca. 2.6 | ca. 0.24 | ca. 200 | N | ca. 9 #b {1:300} | Highest weekly avg. MC of north roof sheathing (within 1 year sim.) = 14% | (0) |

| 17 | Ojanen (2001) [7] | E | Espoo, Finland (1998 – 1999) | Dfb | 22 °C ca. 35 %RH (6 month meas.) 20Pa interior overpress. | ca. 0.001 ** (ca. 0.0002 **) | ca. 10 | ca. 0.15 | ca. 0.02 | Y | ca. 0.1 #i (no intentional vents) | max weekly MC = 18% (6 months meas.) | (0) |

| 5 | Buchan et al. (1991) [11] | I | Ottawa (ON), Canada | Dfb | 18–24 °C 40–60 %RH | ca. 0.11 (ca. 0.03) | ca. 0.4 | ca. 0.19 | ca. 200 | N | ca. 3 {1:490} | max weekly averaged MC = 15.5% | (0) |

| 35 | Essah et al. (2009) [10] | C | United Kingdom | Cfb | 20–25 °C 40–70 %RH (according to high occupancy in the mentioned standard) n50 = 2 h−1 (1 year sim.) | 0.18 * (0.05 *) | ca. 10 | ca. 0.15 | 40 | Y | ca. 3.3 #k {ca. 1:340} (ca. 20 h−1 at 50 Pa p.dif.) (10 mm openings along the eaves) | 43 kg/year of condensate on the attic underlay (ca. 560 g/m2/year) | (1) |

| 36 | Essah et al. (2009) [10] | C | United Kingdom | Cfb | 20–25 °C 30–60 %RH (according to normal occupancy in the mentioned standard) n50 = 2 h−1 (1 year sim.) | 0.18 * (0.05 *) | ca. 10 | ca. 0.15 | 40 | Y | ca. 3.3 #k {ca. 1:340} (ca. 20 h−1 at 50 Pa p.dif.) (10 mm openings along the eaves) | 4 kg/year of condensate on the attic underlay (ca. 53 g/m2/year) | (0) |

| 16 | Ojanen (2001) [7] | E | Espoo, Finland (1998–1999) | Dfb | 22 °C ca. 35 %RH (1 year meas.) (simulated moisture gain by water vessel within the attic) | Simulated by moisture source 0.19#m (0.04)#m real. ca. 0.001 ** (ca. 0.0002 **) | ca. 10 | ca. 0.15 | ca. 0.02 | Y | ca 0.1 #i (no intentional vents) | max weekly MC = 21% (1 year meas.) | (0) |

| 15 | Ojanen (2001) [7] | E | Espoo, Finland (1998–1999) | Dfb | 22 °C ca. 35 %RH (1 year meas.) (simulated moisture gain by water vessel within attic) | Simulated by moisture source 0.19#m (0.04)#m real. ca. 0.001 ** (ca. 0.0002 **) | ca. 10 | ca. 0.15 | ca. 10 | Y | ca. 10#a natural eaves (+ridge) | max weekly MC = 21% (1 year meas.) | (0) |

| 9 | Burch et al. (1996) [4] | C | Madison (WI), USA | Dfb | 20–24 °C ca. 20–60% (1 year sim.) | ca. 0.21#g (ca. 0.016#g) | ca. 2.6 | ca. 0.24 | ca. 200 | N | ca. 1 #b by leakages | highest weekly avg. MC of north roof sheathing (within 1 year sim.) = 28% | (2) |

| 7 | Burch et al. (1996) [4] | C | Madison (WI), Portland (OR), Atlanta (GA); USA | Csb Cfa Dfb | 20–24 °C ca. 20–60% (1 year sim.) | ca. 0.21#g (ca. 0.016#g) | ca. 2.6 | ca. 0.24 | ca. 200 | N | ca. 9 #b {1:300} | highest weekly avg. MC of north roof sheathing (within 1 year sim.) = 16% | (0) |

| 8 | Burch et al. (1996) [4] | C | Boston (MA); USA | Dfb | 20–24 °C ca. 20–60% (1 year sim.) | ca. 0.21#g (ca. 0.016#g) | ca. 2.6 | ca. 0.24 | ca. 200 | N | ca. 9 #b {1:300} | highest weekly avg. MC of north roof sheathing (within 1 year sim.) = 18% | (0) |

| 10 | Burch et al. (1996) [4] | C | Madison (WI), USA | Dfb | 20–24 °C ca. 45–60% (1 year sim.) | ca. 0.21#g (ca. 0.016#g) | ca. 2.6 | ca. 0.24 | ca. 200 | N | ca. 9 #b {1:300} | highest weekly avg. MC of north roof sheathing (within 1 year sim.) = 25% | (0) |

| 23 | Hagentoft et al. (2008) [9] | C | Gothenburg region, Sweden | Cfb | 30–60 %RH; — balanced ventilation (1 year sim.) | 0.22 (0.06) (annual average) | ca. 10 | ca. 0.10 | ca. 12 | Y | ca. 22 *** (130 h−1 at 50 Pa p. dif.) | Mould index = 3.24 # (total of 12 weeks in 90–100 %RH and 0–5 °C; 6 weeks in 80–90 %RH and 5–15 °C; 3 weeks in 70–80 %RH and above 15 °C) | (3) |

| 20 | Sasic Kalagasidis and Mattsson (2005) [2] | C | South-west coastal area of Sweden (wind exposure — city) | Cfb | 22 °C 40–70 %RH (1 year sim.) exhaust—supply ventilation (out 120 m3/h — in 90%) | ca. 0.25 #j (ca. 0.08) (heating season avg.) | ca. 11 | ca. 0.077 | ca. 0.6 | Y | mean 0.1 (unventilated design) | Mould index = 4.9 #,#d (four year simulation) | (3) |

| 18 | Sasic Kalagasidis and Mattsson (2005) [2] | C | South-west coastal area of Sweden (wind exposure — city) | Cfb | 22 °C 40–70 %RH (1 year sim.) exhaust—supply ventilation (out 120 m3/h — in 90%) | ca. 0.25#j (ca. 0.08) (heating season avg.) | ca. 11 | ca. 0.077 | ca. 0.6 | Y | mean 2.2 (natural eave ventilation) | total of 15 weeks in 90–100 %RH and 0–10 °C; 4 weeks in 80–90 %RH and 0–10 °C; 1.8 weeks in 80–90 %RH and 10–20 °C Mould index = 0.25 #,#d (four year simulation) | (2) |

| 19 | Sasic Kalagasidis and Mattsson (2005) [2] | C | South-west coastal area of Sweden (wind exposure — open area) | Cfb | 22 °C 40–70 %RH (1 year sim.) exhaust—supply ventilation (out 120 m3/h — in 90%) | ca. 0.25#j (ca. 0.08) (heating season avg.) | ca. 11 | ca. 0.077 | ca. 0.6 | Y | mean 13.9 (natural eave ventilation) | total of 11 weeks in 90–100 %RH and 0–10 °C; 7 weeks in 80–90 %RH and 0–10 °C; 4 weeks in 80–90 %RH and 10–20 °C Mould index = 0.33#,#d (four year simulation) | (1) |

| 32 | Essah et al. (2009) [10] | C | United Kingdom | Cfb | 20–25 °C 40–70 %RH (according to high occupancy in mentioned standard) n50 = 5 h−1 (1 year sim.) | 0.27 ** (0.07 **) | ca. 0.5 #e | ca. 0.15 | 0.02 | Y | estimated ca 0.1 no intentional openings (roof leakage flow rate is several orders of magnitude lower than intentional ventilation) | 17 kg/year of condensate on the attic underlay (ca. 220 g/m2/year) | (0) |

| 34 | Essah et al. (2009) [10] | C | United Kingdom | Cfb | 20–25 °C 40–70 %RH (according to high occupancy in the mentioned standard) n50 = 5 h−1 (1 year sim.) | 0.36 * (0.1 *) | ca. 0.5 #e | ca. 0.15 | 0.02 | Y | ca. 4.6 #k {ca. 1:170} (28 h−1 at 50 Pa p.dif.) (20 mm openings along the eaves) | 175 kg/year of condensate on the roof underlay (ca. 2300 g/m2/year) | (3) |

| 33 | Essah et al. (2009) [10] | C | United Kingdom | Cfb | 20–25 °C 40–70 %RH (according to high occupancy in the mentioned standard) n50 = 5 h−1 (1 year sim.) | 0.36 * (0.1*) | ca. 0.5 #e | ca. 0.15 | 40 | Y | ca. 4.6 #k {ca. 1:170} (28 h−1 at 50 Pa p.dif.) (20 mm openings along the eaves) | 207 kg/year of condensate on the attic underlay (ca. 2700 g/m2/year) | (3) |

| 37 | Morrison Hershfield (2014) [8] | I | Vancouver (BC), Canada (2011/2012) | Cfb | 24.1 °C 30.7 %RH (winter 2011/2012 averages) | ca. 0.38 (ca. 0.11) | ca. 10.5 | ca. 0.12 | ca. 200 | N | avg. 4.5 ca. 1 - 8 (depending on measurement method) {1:232} baffle vents | Mould index = ca. 4 # (observed and also calculated), worst weekly combination of temperature and moisture content of east sheathing was ca. 13 °C; 25 %MC | (3) |

| 6 | Buchan et al. (1991) [11] | I | Ottawa (ON), Canada | Dfb | 18–21 °C 40–60 %RH | ca. 0.66 (ca. 0.18) | ca. 0.3 | ca. 0.28 | ca. 200 | N | ca. 4.4 {1:250} | max weekly averaged MC = 70.0% | (3) |

| 4 | Buchan et al. (1991) [11] | I | Ottawa (ON), Canada | Dfb | 18–23 °C 30–50 %RH | ca. 0.70 (ca. 0.15) | ca. 0.5 | ca. 0.17 | ca. 200 | N | ca. 11 {1:180} | max weekly averaged MC = 23.5% | (1) |

| 22 | Holm and Lengsfeld (2007) [5] | E | Holzkirchen Germany (12/2003) | Cfb | 20–22 °C 50–60 %RH (3 months meas.) | 1.25 (0.16) | ca. 10 | estimated ca. 0.13 | 0.22 | Y (non-continuous cavity) | ca. 18*** {ca. 1:154} 3 mm eave openings and 20 mm ridge opening | At 11 time points (from Jan. to March), a total of 138 g of condensate was wiped from an area of 0.06 m2 of the underlay foil (i.e., 2300 g/m2) maximum of a single wiping was ca. 30 g/0.06m2 (i.e., 500 g/m2), measured moisture contents of wooden rafters – in weekly averages ca. 23 %MC in 4 °C; 22 %MC in 5 °C; 19 %MC in 8 °C; | (3) |

| 3 | Rowley et al. (1941) [3] | E–lab. | Conditioned chamber | −21 °C (condi.chamb.) | constant. 21 °C 40 %RH (5 days meas.) | ca. 0.05 ** (ca. 0.019 **) | ca. 0.3 | ca. 0.52 | ca. 200 | N | ca 0.3 #a by leakages (no vents) | ca. 52 g/m2/24h of condensate on underlay sheathing | - |

| 2 | Rowley et al. (1941) [3] | E–lab. | Conditioned chamber | −21 °C (condi.chamb.) | constant. 21 °C 40 %RH (6 days meas.) | ca. 0.08 * (ca. 0.03 *) | ca. 0.3 | ca. 0.52 | ca. 200 | N | ca. 4 #a {ca. 1:98} | ca. 12 g/m2/24h of condensate on underlay sheathing | - |

| 1 | Rowley et al. (1941) [3] | E–lab. | Conditioned chamber | −21 °C (condi.chamber) | constant. 21 °C 40 %RH (ca. 2 day meas.) | ca. 0.37 * (ca. 0.14 *) | ca. 0.2 | ca. 0.52 | ca. 200 | N | ca. 3 #a {ca. 1:98} | avg. ca. 75 g/m2/24 h of condensate on underlay sheathing | - |

| 27 | Hagentoft et al. (2008) [9] | C | Gothenburg region, Sweden | Cfb | 30–60 %RH; — balanced ventilation (1 year sim.) | 0 | ca. 10 | ca. 0.10 | ca. 12 | Y | ca. 0.6#f + 1 h−1 when adaptive ventilation is running (unintentional 7 h−1 at 50 Pa p. dif.) | Mould index = 0.00# (total of 0 weeks in 90–100 %RH and 0–5 °C; 0 weeks in 80–90 %RH and 5–15 °C; 0 weeks in 70–80 %RH and above 15 °C) | (0) |

| 25 | Hagentoft et al. (2008) [9] | C | Gothenburg region, Sweden | Cfb | 30–60 %RH; — balanced ventilation (1 year sim.) | ca. 0.1 #c (ca. 0.03#c) (annual average) | ca. 10 | ca. 0.10 | ca. 12 | Y | ca. 0.1#f + 1 h−1 when adaptive ventilation is running (unintentional 1 h−1 at 50 Pa p. dif.) | Mould index = 1.03# (total of 8 weeks in 90–100 %RH and 0–5 °C; 2 weeks in 80–90 %RH and 5–15 °C; 0 weeks in 70–80 %RH and above 15 °C) | (1) |

| 26 | Hagentoft et al. (2008) [9] | C | Gothenburg region, Sweden | Cfb | 30–60 %RH; — balanced ventilation (1 year sim.) | ca. 0.1 #c (ca. 0.03#c) (annual average) | ca. 10 | ca. 0.10 | ca. 12 | Y | ca. 0.1#f + 5 h−1 when adaptive ventilation is running (unintentional 1 h−1 at 50 Pa p. dif.) | Mould index = 0.02# (total of 1 weeks in 90–100 %RH and 0–5 °C; 0 weeks in 80–90 %RH and 5–15 °C; 0 weeks in 70–80 %RH and above 15 °C) | (0) |

| 38 | Morrison Hershfield (2014) [8] | I | Vancouver (BC), Canada (2011/2012) | Cfb | exterior conditions ca. 3–10 °C; 80–95 %RH | no ceiling (roof deck exposed to outdoor cond.) | no ceiling (roof deck exposed to outdoor cond.) | no ceiling (roof deck exposed to outdoor cond.) | ca. 200 | N | fully ventilated (roof deck exposed to outdoor cond.) | Mould index = ca. 4# (observed and also calculated), worst weekly combination of temperature and moisture content of east sheathing was ca. 9 °C; 24 %MC | (3) |

| Text style and colour: black regular—values stated sharply in original study black italics—values calculated directly based on information in original study, or values calculated using common material properties blue italics—values calculated by combining information from original studies and a set of other assumptions (better specified in chapter “Methods” or by note in their upper index) bold—values of the suggested three key parameters Cell background colour: green—refers to the moisture-risk level (0) yellow—refers to the moisture-risk level (1) pink–lab—refers to the moisture-risk level (2) red—refers to the moisture-risk level (3) grey—grey backgrounded are cells with 7 supplementary designs that are not included in the main comparison of the rest 31 main designs Study type: C—computational study E—experimental study E–lab—experimental study under laboratory conditions I—in situ measurement Parameters: nint–att—real interior–attic air change rate under operations (experimental, real, or numerically simulated, related to attic volume) (h−1) Qint–att—real volumetric flux across the ceiling construction under operation (experimental, real, or numerically simulated) (l/s/m2) sd,ceil—equivalent air layer thickness of the ceiling construction (m) Uceil—thermal transmittance of the ceiling construction (W/m2/K) sd_r.deck—equivalent air layer thickness of the roof (m) presence of r.deck cavity—Y (yes), N (no) next–att—real attic air change rate by ventilation with outdoor air (h−1) {vent. ratio}—ratio of the total area of attic ventilation openings and attic floor area (supplementary information based on the well-known 1:300 rule for attic ventilation) Moisture-risk level—level of moisture risk: (0)—no risk (green background); (1)—low risk (yellow background); (2)—medium risk (pink background); (3)—high risk (red background) Other: MC—moisture content (%) Notes: #—according to VTT mould growth model (1999) [55] *—values calculated for 4 Pa interior overpressure using the power law with the exponent 0.67 **—values calculated for 2 Pa interior overpressure using the power law with the exponent 0.67 ***—Air change is calculated for wind speed of 2.5 m/s and wind pressure coefficients (0.25) and (−0.5) on the opposite sides (thus, the total pressure difference across the opposite attic vents is 2.8 Pa). The pressure difference across the inlet openings is assumed to be half of the value (1.4 Pa). For orifice flow, the discharge coefficient is considered as 0.6, the flow exponent is 0.5, and the air density is 1.21 kg/m3. Then, the airflow (m3/s) is ca. 0.9 times the opening area (m2). #a—estimated according to the specified ventilation regime and values of other studies considering the particular experimental design of each study #b—evaluated for wind speed of 2.5 m/s according to the chart provided in the study #c—annual average of ceiling leakage is quantified only for unventilated attics; for well-sealed attics, we consider ca. half the values of unventilated attics #d—calculated by the authors of this paper using data provided by prof. Sasic Kalagasidis (the VTT mould growth model (1999) [55] was used for calculation) #e—no information on the vapour barrier was found within the study #f—calculated using the power law with a flow exponent of 0.67 and a pressure difference of 1.4 Pa (corresponding to the surrounding wind speed of ca. 2.5 m/s; see note ***) #g—based on the many data provided in this study (since the main set of provided equations was found to be incorrect) #h—based on the assembly specifications and determined air permeance values for air-barriers without any joints [64] #i—calculated based on the provided air-permeability data of the underlay, multiplying the value by 3x and using the power law with a flow exponent of 0.67 and a pressure difference of 1.4 Pa #j—evaluated based on the chart provided within the study #k—calculated based on the stated air change rate at a 50 Pa pressure difference using the orifice flow equation for the 1.4 Pa pressure difference (see note ***) #l—calculated based on the set of equations provided within the original study (the building air change rate = 5 or 2 h−1; parameter b = 0.25) #m—Based on 1 g/h/m2 (of the ceiling area) being provided to the attic (an interior 7 g/m3 concentration of water vapour was considered). | |||||||||||||

| Real Interior–Attic Air Change Rate Class | Roof-Deck Vapour Permeance Class | Exterior–Attic Air Change Rate Class | Attic Design No. and Evaluated Moisture Risk (in Brackets) |

|---|---|---|---|

| extremely low | permeable | unventilated | 17(0), 31(0) |

| slightly ventilated | |||

| ventilated | |||

| medium permeable | unventilated | 13(0), 30(2), 21(0) | |

| slightly ventilated | |||

| ventilated | 14(2) | ||

| vapour-tight | unventilated | 29(3) | |

| slightly ventilated | 12(2) | ||

| ventilated | 11(0), 28(0), 24(1) | ||

| low | permeable | unventilated | |

| slightly ventilated | |||

| ventilated | |||

| medium permeable | unventilated | ||

| slightly ventilated | |||

| ventilated | |||

| vapour-tight | unventilated | ||

| slightly ventilated | |||

| ventilated | |||

| medium | permeable | unventilated | |

| slightly ventilated | |||

| ventilated | |||

| medium permeable | unventilated | ||

| slightly ventilated | |||

| ventilated | |||

| vapour-tight | unventilated | ||

| slightly ventilated | 36(0), 5(0), 35(1) | ||

| ventilated | |||

| heavy | permeable | unventilated | 16(0), 32(0) |

| slightly ventilated | |||

| ventilated | 34(3), 22(3) | ||

| medium permeable | unventilated | 20(3) | |

| slightly ventilated | 18(2) | ||

| ventilated | 19(1) | ||

| vapour-tight | unventilated | ||

| slightly ventilated | 9(2) | ||

| ventilated | 7(0), 8(0), 10(0), 15(0), 4(1), 6(3), 33(3), 23(3), 37(3) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Richter, J.; Staněk, K.; Tywoniak, J.; Kopecký, P. Moisture-Safe Cold Attics in Humid Climates of Europe and North America. Energies 2020, 13, 3856. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13153856

Richter J, Staněk K, Tywoniak J, Kopecký P. Moisture-Safe Cold Attics in Humid Climates of Europe and North America. Energies. 2020; 13(15):3856. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13153856

Chicago/Turabian StyleRichter, Jan, Kamil Staněk, Jan Tywoniak, and Pavel Kopecký. 2020. "Moisture-Safe Cold Attics in Humid Climates of Europe and North America" Energies 13, no. 15: 3856. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13153856

APA StyleRichter, J., Staněk, K., Tywoniak, J., & Kopecký, P. (2020). Moisture-Safe Cold Attics in Humid Climates of Europe and North America. Energies, 13(15), 3856. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13153856