Towards Self-Sustainable Island Grids through Optimal Utilization of Renewable Energy Potential and Community Engagement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Different Aspects of Self-Sustainable Island Grids

2.1. Factors Influencing Willingness to Participate in Sustainable Energy Systems

2.1.1. Community Identity and Trust

2.1.2. Social Norms

2.1.3. Environmental Attitudes

2.1.4. Economic Benefits

2.1.5. Island Communities and Sustainable Community Energy Projects

2.1.6. Sociotechnical Implications

2.1.7. Policy Barriers

2.2. Renewable Energy Potential

2.2.1. Methods for Production Estimation

2.2.2. Data Availability

2.3. Planning and Optimization

3. Simulation Methodology

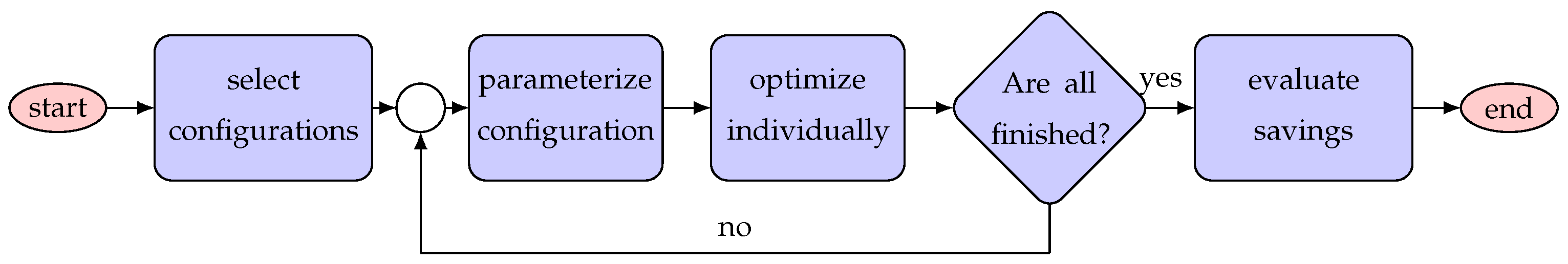

3.1. Optimization Procedure

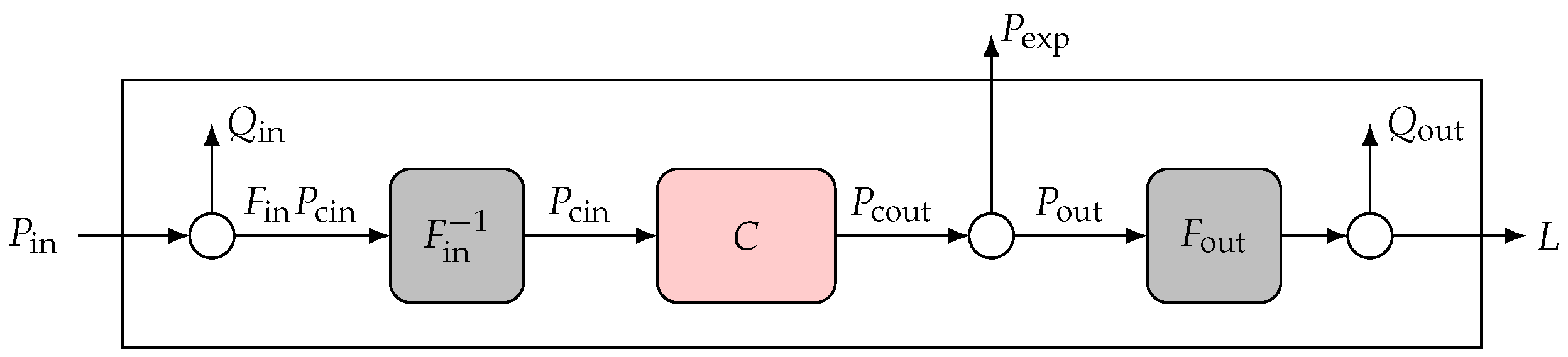

3.2. Operational Optimization Model

3.3. Load Flexibility Model

3.4. Implementation

4. Use Case Definition

4.1. End User Engagement

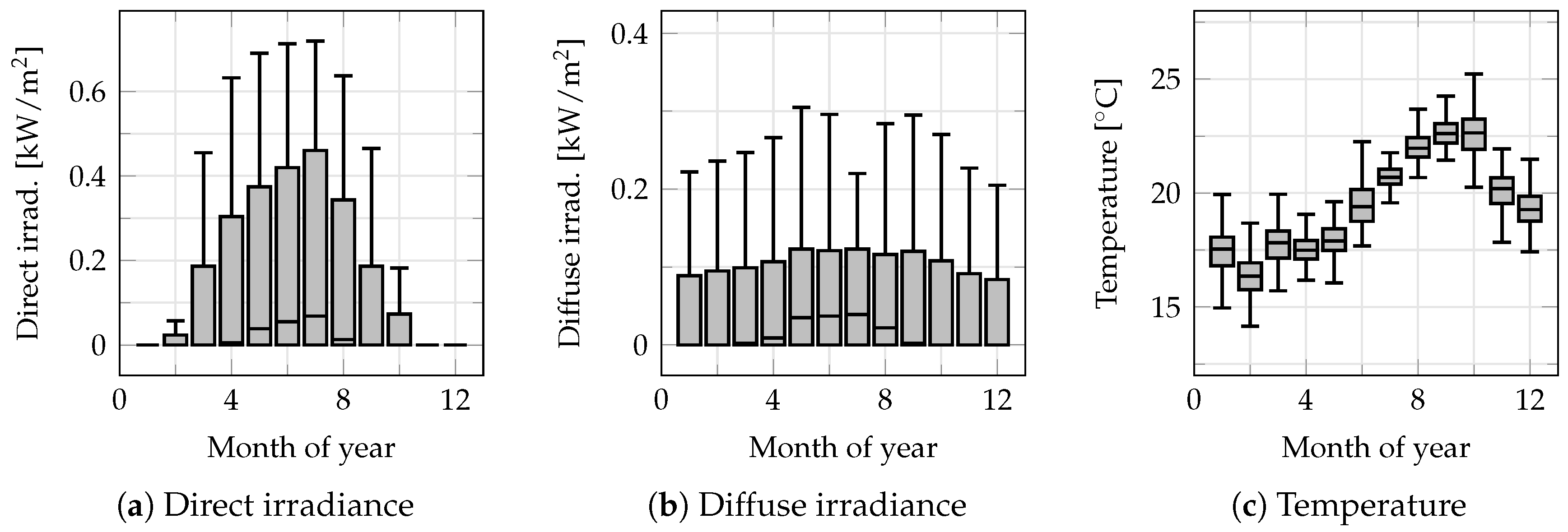

4.2. Renewable Energy Generation

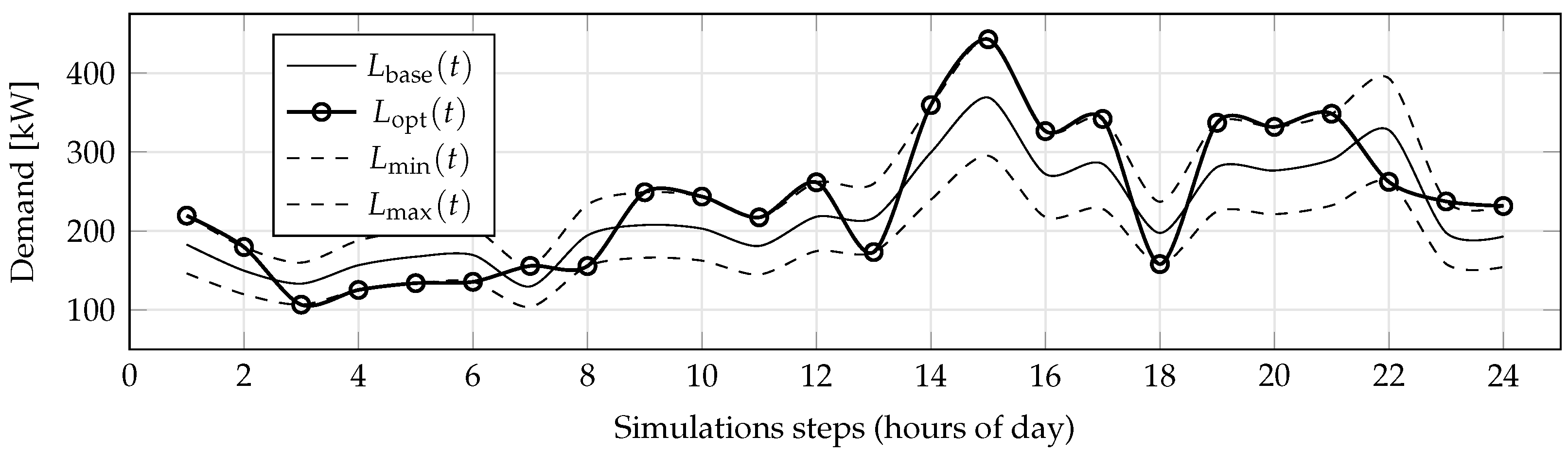

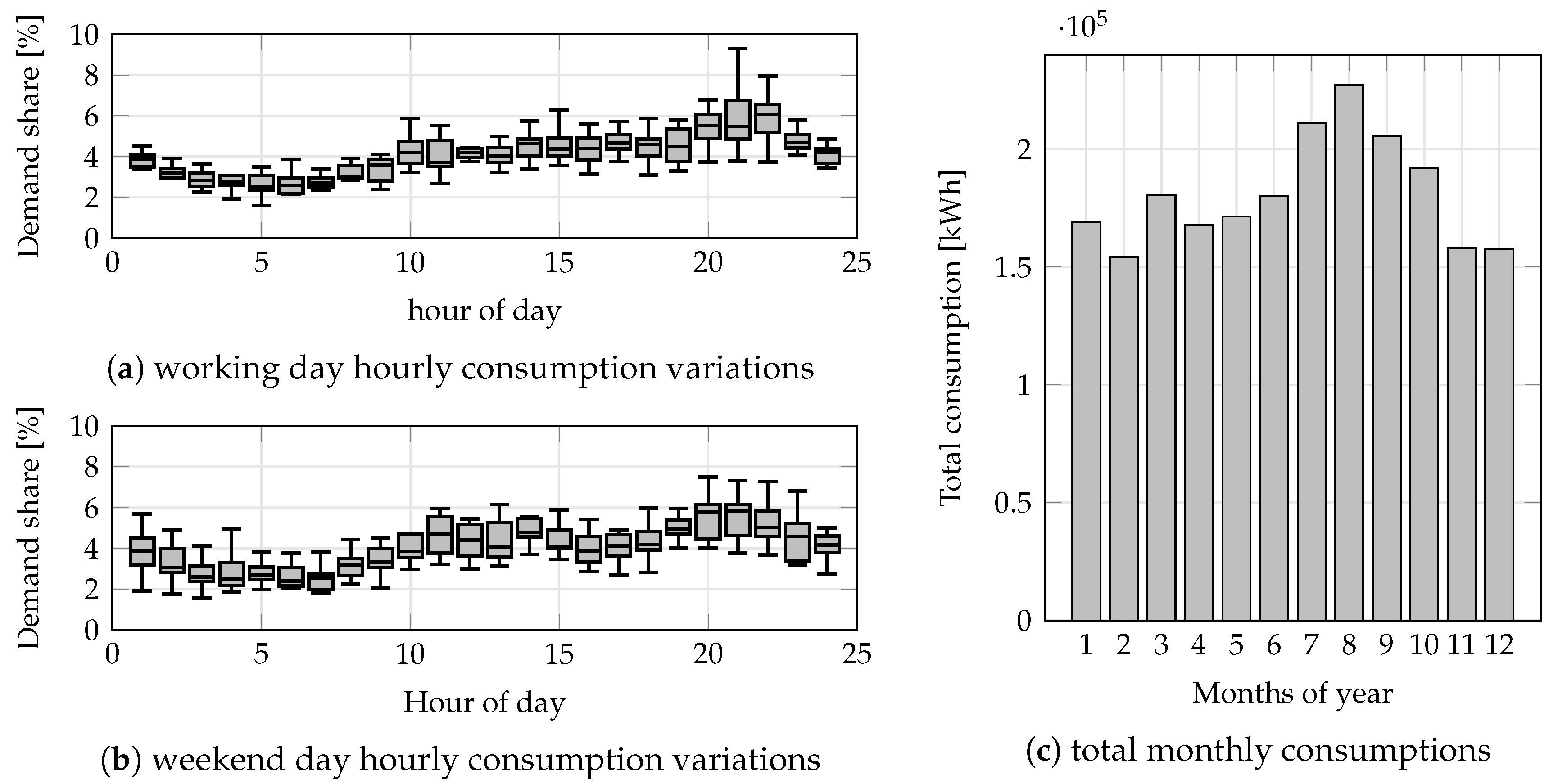

4.3. Demand Profile

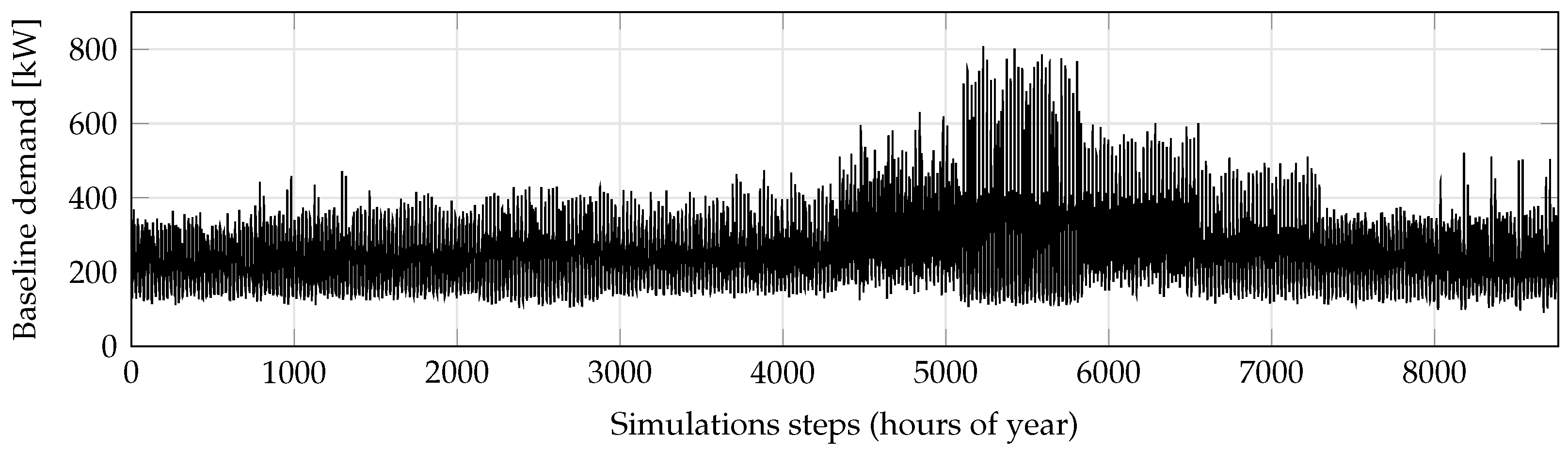

4.4. Pricing Profile

4.5. Optimization Setup

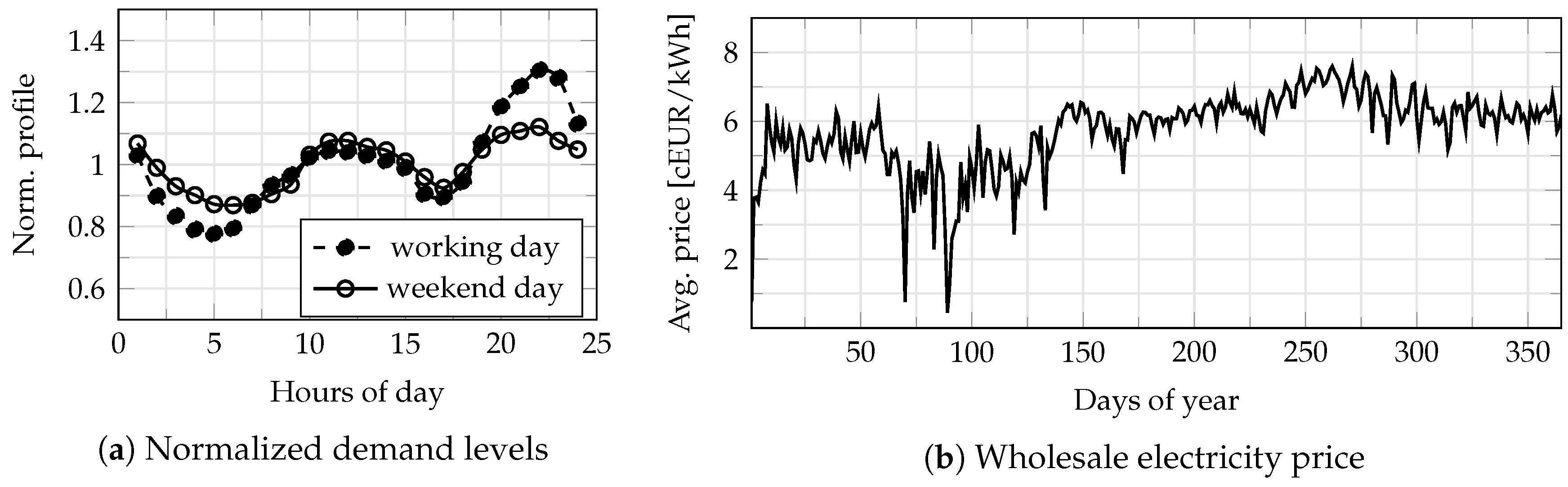

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Simulation Outputs

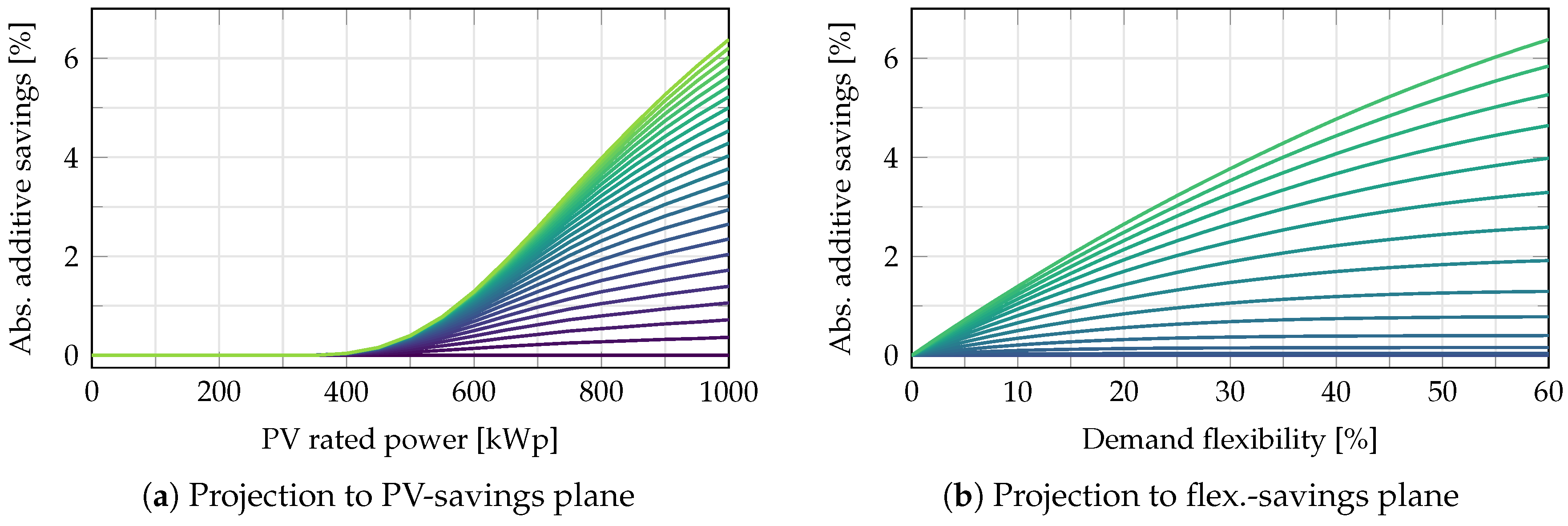

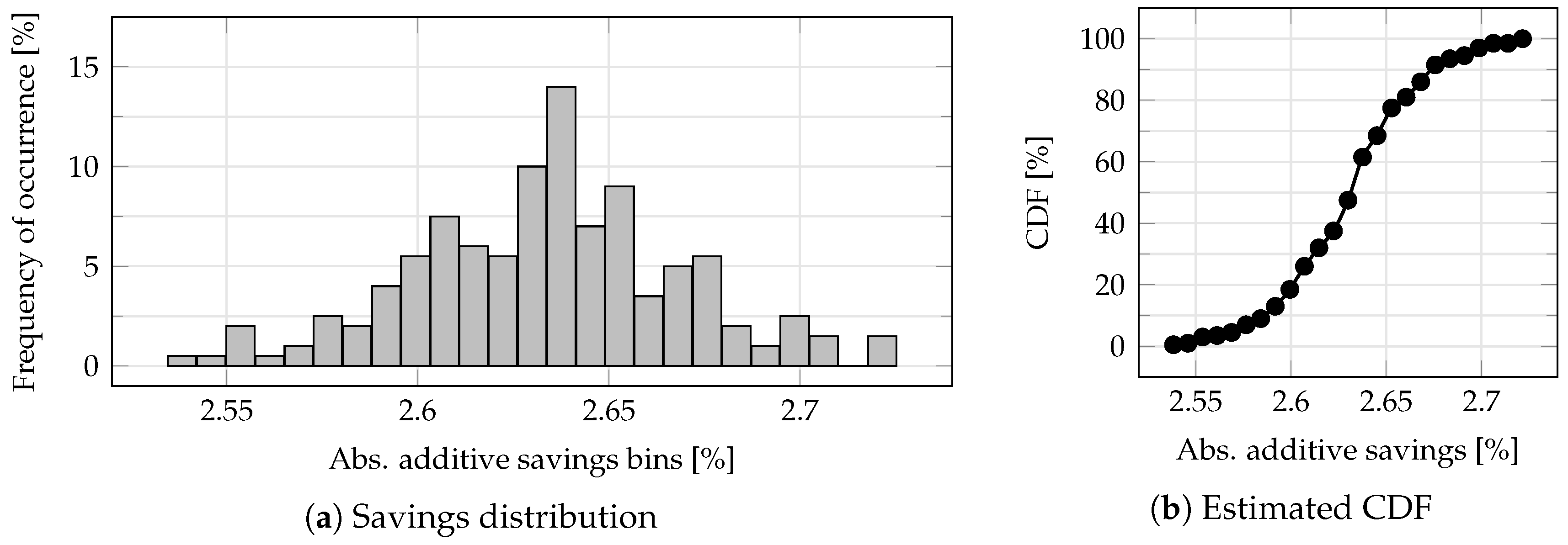

5.2. Sensitivity Analysis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ghanem, D.A.; Mander, S.; Gough, C. “I think we need to get a better generator”: Household resilience to disruption to power supply during storm events. Energy Policy 2016, 92, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christine, D.; Kathryn, L.; Sarah, J.; Kazuhiko, I.; Thomas, M. Health Impacts of Citywide and Localized Power Outages in New York City. Environ. Health Perspect. 2018, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uche-Soria, M.; Rodríguez-Monroy, C. Energy planning and its relationship to energy poverty in decision making. A first approach for the Canary Islands. Energy Policy 2020, 140, 111423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). A Path to Prosperity: Renewable Energy for Islands; International Renewable Energy Agency: Bonn, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Smart Islands Initiative. Smart Islands Declaration: New Pathways for European Islands; Smart Islands Initiative 2017. Available online: www.smartislandsinitiative.eu (accessed on 22 May 2020).

- Gangale, F.; Mengolini, A.; Onyeji, I. Consumer engagement: An insight from smart grid projects in Europe. Energy Policy 2013, 60, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbong, G.P.J.; Beemsterboer, S.; Sengers, F. Smart grids or smart users? Involving users in developing a low carbon electricity economy. Energy Policy 2013, 52, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudy, M.C.; Michelsen, C.; O’Driscoll, A.; Mullen, M.R. Consumer awareness in the adoption of microgeneration technologies: An empirical investigation in the Republic of Ireland. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 2154–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, J.; Tengvard, M. Motives for and barriers to household adoption of small-scale production of electricity: Examples from Sweden. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2011, 7, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkbrenner, B.J.; Roosen, J. Citizens’ willingness to participate in local renewable energy projects: The role of community and trust in Germany. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauwens, T. Explaining the diversity of motivations behind community renewable energy. Energy Policy 2016, 93, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vugt, M.V. Central, Individual, or Collective Control?: Social Dilemma Strategies for Natural Resource Management. Am. Behav. Sci. 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammami, S.M.; chtourou, S.; Triki, A. Identifying the determinants of community acceptance of renewable energy technologies: The case study of a wind energy project from Tunisia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.; Devine-Wright, P.; Hunter, S.; High, H.; Evans, B. Trust and community: Exploring the meanings, contexts and dynamics of community renewable energy. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 2655–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.M.; Sandoval, H.; Acosta, P.; Henao, F. On the Acceptance and Sustainability of Renewable Energy Projects—A Systems Thinking Perspective. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, P.C.; Maki, A.; Rothman, A.J. Promoting energy conservation behavior in public settings: The influence of social norms and personal responsibility. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 41, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadenne, D.; Sharma, B.; Kerr, D.; Smith, T. The influence of consumers’ environmental beliefs and attitudes on energy saving behaviours. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 7684–7694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulugetta, Y.; Jackson, T.; van der Horst, D. Carbon reduction at community scale. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7541–7545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Valiñas, M.A.; Macintyre, A.; Torgler, B. Volunteering, pro-environmental attitudes and norms. J. Socio-Econ. 2012, 41, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.; Cass, N. Carbon reduction, ‘the public’ and renewable energy: Engaging with socio-technical configurations. Area 2007, 39, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummer, V. Community energy—Benefits and barriers: A comparative literature review of Community Energy in the UK, Germany and the USA, the benefits it provides for society and the barriers it faces. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 94, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomberg, E.; McEwen, N. Mobilizing community energy. Energy Policy 2012, 51, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dóci, G.; Vasileiadou, E. “Let’s do it ourselves” Individual motivations for investing in renewables at community level. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 49, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Schoor, T.; Scholtens, B. Power to the people: Local community initiatives and the transition to sustainable energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 43, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, T.H.; Friis, F.; Bettin, S.; Throndsen, W.; Ornetzeder, M.; Skjølsvold, T.M.; Ryghaug, M. The role of competences, engagement, and devices in configuring the impact of prices in energy demand response: Findings from three smart energy pilots with households. Energy Policy 2020, 137, 111142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, K. How does a pioneer community energy project succeed in practice? The case of the Samsø Renewable Energy Island. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 71, 884–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouly de Lesdain, S. The photovoltaic installation process and the behaviour of photovoltaic producers in insular contexts: The French island example (Corsica, Reunion Island, Guadeloupe). Energy Effic. 2019, 12, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, P.; Vine, D.; Buys, L. Critical Success Factors for Peak Electricity Demand Reduction: Insights from a Successful Intervention in a Small Island Community. J. Consum. Policy 2018, 41, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, L.T.; Iniewski, K. Smart Grid Applications, Communications, and Security; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Anuebunwa, U.R.; Rajamani, H.S.; Pillai, P.; Okpako, O. Evaluation of user participation capabilities in demand response programs for smart home applications. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE PES PowerAfrica, Accra, Ghana, 27–30 June 2017; pp. 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Paranjape, R.; Sadanand, A.; Chen, Z. Residential demand response: An overview of recent simulation and modeling applications. In Proceedings of the 2013 26th IEEE Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (CCECE), Regina, SK, Canada, 5–8 May 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Ming, Z. Modeling demand response under time-of-use pricing. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Power System Technology, Chengdu, China, 20–22 October 2014; pp. 1948–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosbie, T.; Broderick, J.; Short, M.; Charlesworth, R.; Dawood, M. Demand Response Technology Readiness Levels for Energy Management in Blocks of Buildings. Buildings 2018, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, R.; Woodman, B. Barriers to Independent Aggregators in Europe (EPG Working Paper: EPG1901); University of Exeter: Exeter, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Crosbie, T.; Vukovic, V.; Short, M.; Dawood, N.; Charlesworth, R.; Brodrick, P. Future Demand Response Services for Blocks of Buildings. In Smart Grid Inspired Future Technologies; Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering; Hu, J., Leung, V.C.M., Yang, K., Zhang, Y., Gao, J., Yang, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 118–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart Energy Demand Coalition (SEDC). Smart Energy Demand Coalition: A Demand Response Action Plan for Europe; Smart Energy Demand Coalition (SEDC): Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, D.L.; Holladay, C.G.; Barchet, W.R.; Foote, H.P.; Sandusky, W.F. Wind Energy Resource Atlas of the United States. 1987. Available online: rredc.nrel.gov (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Reno, M.; Hansen, C.; Stein, J. Global Horizontal Irradiance Clear Sky Models: Implementation and Analysis; Sandia National Laboratories: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Departmant of Energy. New Stream-Reach Hydropower Development; US Departmant of Energy: Washinton, DC, USA, 2014.

- World Bank Group. Global Solar Atlas; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- NEWA. About the New European Wind Atlas. 2019. Available online: map.neweuropeanwindatlas.eu (accessed on 4 April 2020).

- Natural Resources Canada. RETScreen; Natural Resources Canada: Ottawa, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Barthelmie, R.J.; Wang, H.; Doubrawa, P.; Pryor, S.C. Best Practice For Measuring Wind Speeds and Turbulence Offshore Through In-Situ And Remote Sensing Technologies; report; eCommons: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wees, J.-D.; Boxem, T.; Calcagno, P.; Dezayes, C.; Lacasse, C.; Manzella, A. GEOELEC Project Deliverable 2.1: A Methodology for Resource Assessment and Application to Core Countries. 2013. Available online: www.geoelec.eu (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Sierra, J.P.; González-Marco, D.; Sospedra, J.; Gironella, X.; Mösso, C.; Sánchez-Arcilla, A. Wave energy resource assessment in Lanzarote (Spain). Renew. Energy 2013, 55, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, F.; Lidderdale, A.; Dick, C.; Richon, J.; Porter, K.; Maisondieu, C.; Johnston, C. MARINET Project Deliverable 4.11: Report New Instrumentation and Field Measuring Technology for Tidal Currents. 2015. Available online: www.marinet2.eu (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Cassar, D.; Erika, M.; Evangelos, R.; Christoforos, P.; Pfeifer, A.; Groppi, D.; Krajacic, G.; Garcia, D.A. A Methodology for Energy Planning in Small Mediterranean Islands, the Case of the Gozo Region. In Proceedings of the 2019 1st International Conference on Energy Transition in the Mediterranean Area (SyNERGY MED), Cagliari, Italy, 28–30 May 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, S.; Kougias, I.; Moner-Girona, M.; Bódis, K. Sustainable Energy Portfolios for Small Island States. Sustainability 2015, 7, 12340–12358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominković, D.F.; Stark, G.; Hodge, B.M.; Pedersen, A.S. Integrated Energy Planning with a High Share of Variable Renewable Energy Sources for a Caribbean Island. Energies 2018, 11, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uche-Soria, M.; Rodríguez-Monroy, C. Special Regulation of Isolated Power Systems: The Canary Islands, Spain. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chalvatzis, K.J.; Stephanides, P. Innovative Energy Islands: Life-Cycle Cost-Benefit Analysis for Battery Energy Storage. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Yang, L. Simulation of the integrated energy system for isolated island. In Proceedings of the 2017 China International Electrical and Energy Conference (CIEEC), Beijing, China, 25–27 October 2017; pp. 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poncela, M.; Purvins, A.; Chondrogiannis, S. Pan-European Analysis on Power System Flexibility. Energies 2018, 11, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finck, C.; Li, R.; Zeiler, W. Optimal control of demand flexibility under real-time pricing for heating systems in buildings: A real-life demonstration. Appl. Energy 2020, 263, 114671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Geneidy, R.; Howard, B. Contracted energy flexibility characteristics of communities: Analysis of a control strategy for demand response. Appl. Energy 2020, 263, 114600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favre-Perrod, P. A vision of future energy networks. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE Power Engineering Society Inaugural Conference and Exposition in Africa, Durban, South Africa, 11–15 July 2005; pp. 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batić, M.; Tomašević, N.; Beccuti, G.; Demiray, T.; Vraneš, S. Combined energy hub optimisation and demand side management for buildings. Energy Build. 2016, 127, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salom, J.; Marszal, A.J.; Widén, J.; Candanedo, J.; Lindberg, K.B. Analysis of load match and grid interaction indicators in net zero energy buildings with simulated and monitored data. Appl. Energy 2014, 136, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, A.; Polatidis, H. REACT Project Deliverable 2.1: Assessment of RES Potential at Pilot Sites. REACT: Catalonia, Spain, 2019; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Jelić, M.; Tomašević, N.; Pujić, D.; Biosca, L.M.; Fabres, J.; Totschnig, G. REACT Project Deliverable 2.2: RES/storage enabled infrastructure planning. REACT: Catalonia, Spain, 2019; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanem, D.A.; Crosbie, T. REACT Project Deliverable 4.1: Criteria and framework for participant recruitment. REACT: Catalonia, Spain, 2020; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Canary Islands Technological Institute (ITC). Plan de Acción Insular para la Sostenibilidad Energética para La Graciosa (2012-20); Canary Islands Technological Institute (ITC): Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, 2013; Available online: www.datosdelanzarote.com (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Consiglio Nazionale dei Geologi. Geotermia; Consiglio Nazionale dei Geologi: Rome, Italy, 2019; Available online: www.cngeologi.it (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Luis Manuel Santana Perez. El clima de La Graciosa, 2016. Available online: www.agrolanzarote.com (accessed on 28 April 2020).

- SISIFO. DataInput—Simulación Fotovoltaica; SISIFO: Madrid, Spain, 2019; Available online: www.sisifo.info (accessed on 28 April 2020).

- Comune di Carloforte—Isola Ecologica del Mediterraneo. Piano d’azione per l’energia Sostenibile; Comune di Carloforte—Isola Ecologica del Mediterraneo, 2012. Available online: https://mycovenant.eumayors.eu/docs/seap/3594_1339169680.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2020).

- Global Modeling and Assimilation Office (GMAO). Energía Geotérmica—CanariWiki; GMAO: Greenbelt, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ecar Energy Ltd.; ESB International and Mullany Engineering Consultancy Ltd. All Electric Aran Islands Concept: A Design for a Wind and Ocean Powered System Prepared for the He Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland & Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht; Ecar Energy Ltd., ESB International and Mullany Engineering Consultancy Ltd.: Dublin, Ireland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico. La Graciosa. 2019. Available online: www.miteco.gob.es (accessed on 28 April 2020).

- Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y la Competencia. Resolución de 11 de diciembre de 2019. BOE-A-2019-18423, 307, 139647-139668, 2019. Available online: www.boe.es (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Gelaro, R.; McCarty, W.; Suárez, M.J.; Todling, R.; Molod, A.; Takacs, L.; Randles, C.A.; Darmenov, A.; Bosilovich, M.G.; Reichle, R.; et al. The Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2). J. Clim. 2017, 30, 5419–5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfenninger, S.; Staffell, I. Long-term patterns of European PV output using 30 years of validated hourly reanalysis and satellite data. Energy 2016, 114, 1251–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OMIE. Electricity Market | OMIE; OMIE: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2018; International Renewable Energy Agency: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Environmental Agency. Achieving Energy Efficiency through Behaviour Change: What Does It Take; European Environmental Agency: Copenhagen, Demark, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Label | Unit | Description | Label | Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imported power variable vector to the Energy Hub | Load flexibility level | ||||

| Charge/discharge variable vector from input storage of the Energy Hub | J, | any, | Criterion function and operational costs as a criterion function | ||

| Power inflow variable vector to the conversion stage of the Energy Hub | , | Hourly and monthly noise levels | |||

| Power outflow variable vector from the conversion stage of the Energy Hub | , | Grid transformer and invertor efficiency | |||

| Exported power variable vector from the Energy hub | Initial (equipment) acquisition cost | ||||

| Charge/discharge variable vector from output storage of the Energy Hub | Expected (equipment) lifetime | ||||

| Load variable vector of the Energy Hub | Monthly discount rate | ||||

| , | Lower and upper load flexibility margins | Monthly expenditure | |||

| Predicted load level | Total costs of running the system |

| Motivation | Description | Relevance to Island Communities | Focus Case Island La Graciosa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community identity | An intention and desire to make the community better for everyone; benefits oriented to the community and away from the self. | Securing supply for the island and becoming more energy autonomous. Financial savings from the community energy project being re-directed to other community projects/investments; integrating with the community and having shared experiences. | The majority of respondents are ‘motivated’ or ‘strongly motivated’ by environmental and altruistic values suggesting a strong community identity. For example, 75% of respondents from La Graciosa, report that they are motivated to use smart grid technologies by a desire to reduce CO2 emissions. |

| Financial | Save on energy bills; receive financial rewards from energy supplier. | Lower energy costs due to better security of supply. | 74% of respondents in La Graciosa indicate that energy saving is very important to them. |

| Environmental | Reducing CO2 emissions; increasing the sustainability of the island community | Taking action on CO2 reductions empowers island communities in the face of climate change. | 80% of the respondents from La Graciosa report that the use of renewable energy technologies is very important to them. |

| Social norms | Following the example of others in the community; being sensitive to the opinion of others. | The size and closeness of communities driving a sense of togetherness and responsibility, generating positive social norms. | Social norms pertaining to sustainability and high-end technologies are reported as ‘strongly motivating’ with 71% of respondents in La Graciosa being interested in attaining a sustainable character for their homes. |

| Island | Annual Average Wind Speed at 10 m Height [] | Annual Average Hourly Global Horizontal Rrradiance [] | Average Annual Wave Power Density [] | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| La Graciosa | 4.1 | 205.7 | 31.0 | [45,64,65] |

| San Pietro | 6.1 | 171.5 | N/A | [66] |

| Aran Islands | 7.0 | 128.6 | 20.8 | [67,68] |

| dem. flex. [%] | PV Rated Power [kWp] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 400 | 600 | 800 | 1000 | |

| 10 | 0.02 (0.1) | 0.39 (1.4) | 0.80 (2.2) | 1.06 (2.6) |

| 15 | 0.03 (0.2) | 0.69 (2.4) | 1.51 (4.3) | 2.04 (5.0) |

| 20 | 0.04 (0.2) | 0.84 (2.9) | 1.93 (5.4) | 2.65 (6.4) |

| 25 | 0.04 (0.2) | 0.96 (3.3) | 2.31 (6.5) | 3.23 (7.8) |

| 30 | 0.04 (0.2) | 1.06 (3.7) | 2.66 (7.5) | 3.77 (9.2) |

| 35 | 0.04 (0.2) | 1.13 (3.9) | 2.96 (8.3) | 4.29 (10.4) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jelić, M.; Batić, M.; Tomašević, N.; Barney, A.; Polatidis, H.; Crosbie, T.; Abi Ghanem, D.; Short, M.; Pillai, G. Towards Self-Sustainable Island Grids through Optimal Utilization of Renewable Energy Potential and Community Engagement. Energies 2020, 13, 3386. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13133386

Jelić M, Batić M, Tomašević N, Barney A, Polatidis H, Crosbie T, Abi Ghanem D, Short M, Pillai G. Towards Self-Sustainable Island Grids through Optimal Utilization of Renewable Energy Potential and Community Engagement. Energies. 2020; 13(13):3386. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13133386

Chicago/Turabian StyleJelić, Marko, Marko Batić, Nikola Tomašević, Andrew Barney, Heracles Polatidis, Tracey Crosbie, Dana Abi Ghanem, Michael Short, and Gobind Pillai. 2020. "Towards Self-Sustainable Island Grids through Optimal Utilization of Renewable Energy Potential and Community Engagement" Energies 13, no. 13: 3386. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13133386

APA StyleJelić, M., Batić, M., Tomašević, N., Barney, A., Polatidis, H., Crosbie, T., Abi Ghanem, D., Short, M., & Pillai, G. (2020). Towards Self-Sustainable Island Grids through Optimal Utilization of Renewable Energy Potential and Community Engagement. Energies, 13(13), 3386. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13133386