Abstract

We present a review of the current state of the field for a rapidly evolving group of technologies related to solar energy harvesting in built environments. In particular, we focus on recent achievements in enabling the widespread distributed generation of electric energy assisted by energy capture in semi-transparent or even optically clear glazing systems and building wall areas. Whilst concentrating on recent cutting-edge results achieved in the integration of traditional photovoltaic device types into novel concentrator-type windows and glazings, we compare the main performance characteristics reported with these using more conventional (opaque or semi-transparent) solar cell technologies. A critical overview of the current status and future application potential of multiple existing and emergent energy harvesting technologies for building integration is provided.

1. Introduction

Worldwide annual energy consumption is projected to exceed 700 quadrillion British thermal units (Btu), or 0.74 billion TJ by 2040, with the energy generation contributions from fuels other than coal (mainly renewables) being on the increase currently [1]. Around 22.7 billion tons of anthracite coal fuel is needed to release the thermal energy equivalent of to this annual energy consumption figure. At the same time, the combustion of fossil fuels remains among the main concerns identified in relation to the past and current global warming and environmental pollution trends [2,3,4]. Considering this, the development of various types of energy-saving approaches and novel energy generation technologies is of increasing importance today, especially in the building and construction sectors where a substantial fraction of the total energy generated worldwide is being used. In the US and the EU, buildings now account for over 40% of the total energy consumption [5]. At present, the technologies for on-site distributed renewable energy generation in built environments are experiencing rapid advances, yet their widespread utilization is still some years away from being commonplace with one exception, the ubiquitous deployment of conventional photovoltaics (PV) on residential building roofs. Building-integrated PV (BIPV) technologies, in a variety of possible implementations, are widely expected to play a large (and growing) role in near-future construction practices, complementing the now-mature energy-saving construction technologies. A recent report by the European Commission [6] specifies a new societal mission that could be called “creating the Internet of Electricity.” This new term means achieving the fundamental transformation of the power system based on widespread and distributed use of renewables, integrating energy storage, transmission, dispatchment through the smart use of energy consumption. This “Internet of Electricity” is now seen as a fundamental step towards the full integration and decarbonisation of the entire energy system.

Energy-efficient buildings, construction materials, windows, and vehicles are gaining significant attention and increasing importance today [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. The on-site generation of renewable energy coupled with using energy-efficient construction materials and energy-saving appliances forms a viable, future-proof approach to building the infrastructure and vehicles of tomorrow, in practically all geographic regions. The concept of a zero-energy building (ZEB) was first mentioned in 2000 and became a mainstream idea by 2006 [14]. Technologies for enabling widespread heating and also cooling-related energy savings in buildings through reducing the thermal emittance of glass surfaces have a much longer history, dating back to at least the early 1970′s [15,16]. Since then, a large number of research works have been dedicated to achieving continually improved control over the various performance aspects of modern energy-efficient coatings and window glazings, such as their visible-range light transmission (VLT), solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC), thermal insulation performance (U-value), and the ability to control window tint actively or passively. Excellent reviews of key developments in these areas are now available [17,18]. Among the more novel, recently-developed approaches to preventing the overheating of building surfaces are the use of coatings for “passive radiative cooling,” which force the re-emission of the absorbed thermal energy within the atmospheric infrared transparency window between 8 and 13 μm, thus, utilizing the vacuum of space as a heat sink [10,11]. In recent years, the now-traditional spectrally-selective metal-dielectric low-emissivity coatings have found an additional niche application area, serving as components of novel energy-harvesting photovoltaic solar windows [19,20,21], whilst maintaining their energy-saving functionality at the same time. Multiple BIPV-based solar and solar-thermal energy harvesting approaches now form the foundations for a diverse group of mature, industry-ready technologies, with their application areas and markets growing rapidly [22,23,24,25]. At the same time, most semi-transparent, and especially highly-transparent BIPV product types, are only beginning to fill their potentially widespread, yet still, niche-type, application areas, and are at present widely considered as “disruptive technologies”, due to their relatively short history of development and commercialisation [26].

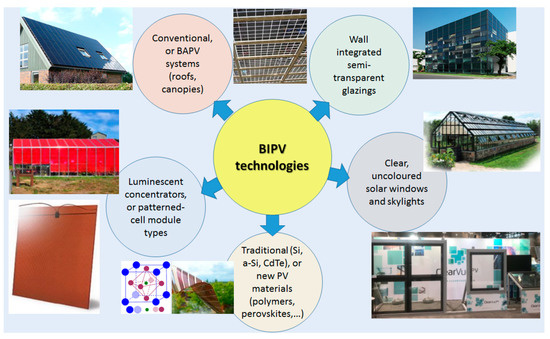

Comprehensive reports and reviews on the types of modern BIPV installations, their economics, performance, and current industry trends are available from [27,28,29,30]. Large-scale installations of semi-transparent BIPV module types in building facades still remain much rarer than conventional BIPV roofs, canopies, façades, and wall coverages, whether colour-adjusted or conventional. Figure 1 provides a graphical summary of the broad range of the building-applied PV (BAPV) and also BIPV technologies, materials, modules, and application types, which are either in common use at present, or beginning to appear on the market.

Figure 1.

Building-integrated photovoltaic (BIPV) modules, technologies, applications, and materials—conventional and emergent.

Energy generation (or energy harvesting) has not traditionally been associated with building walls, windows, or any glazing products, until (perhaps) the current decade. Various approaches to the incorporation of photovoltaic (PV) systems into building envelopes began being actively explored in the last several years, leading to significant growth in this new field of building-integrated photovoltaics. Historically, the building-integrated solar energy harvesting installations started as façade- and wall-integrated conventional (Si, CdTe, or CuIn(Ga)Se2) PV modules occupying the building envelope areas other than roof surfaces, and continued towards the development of semi-transparent, glass-integrated PV window systems using patterned amorphous-silicon modules, perovskite-based, or dye-sensitised solar cells, e.g., [26,30,31,32,33,34,35].

More recently, the field of luminescent solar concentrators (LSCs, [36,37,38]) has begun showing clear signs of a “renaissance” [39,40,41,42]. There has also been significant progress demonstrated in the development of semi-transparent organic, polymer-type, and also perovskite-based solar cells, and organic materials-based transparent LSC [43,44,45,46], driven by the opportunities to capture the growing markets in both distributed electricity generation and advanced construction [6,19,20,31]. Up to date, practically no installation-ready solar windows using transparent organic solar cells or LSC have been marketed as industry standards-compliant building material products.

Windows and glazing systems, despite being a practically ancient technology at its core, are now starting to be viewed and recognised as being the renewable energy platform and resource of the near future [26,47]. This potential for enabling extremely widespread energy harvesting at the point of use is practically unparalleled, considering the entire history of industrial energy generation, and is expected to develop hand-in-hand with the growing use of transparent heat-regulating (THR) coatings for energy-saving applications. Expanding the worldwide energy generation facilities into the almost-uncharted, yet vast territory of glass and windows will require significant time, research efforts, broad-based investments, and long-term strategic thinking on behalf of governments and private companies. This is due to the fundamental and crucial ways in which the energy industry differs from all other industries, which has been underscored in a recent publication [48] by the Breakthrough Energy Coalition, authored by B. Gates. The field of distributed, building-based energy generation and the era of the Internet of Electricity are both in their infancy today, with major new developments and discoveries still waiting to happen. Despite the intrinsic challenge of generating appreciable amounts of electric energy from sunlight using energy-capturing components which themselves require substantially visible transparency, significant progress has been demonstrated in BIPV technologies in recent years. The main aim of this present work is to highlight the important recent developments in the approaches, materials, structures, and systems dedicated to making widely distributed renewable energy generation in built environments a reality. The next sections of this article are structured to first describe (within Section 2) a wide range of technologies available currently for enabling solar energy capture from building surfaces, and their main metrics parameters; other sections are dedicated to describing the principal development milestones relevant to next-generation BIPV achieved recently in both research labs and in industry. Development progress over the last decade in two different classes of BIPV systems—the semitransparent non-concentrating solar modules, and in semitransparent solar concentrators—is reviewed, clearly separating the results achieved in research samples from product-level datasets. Main concentrator-type solar window metrics parameters and the physical effects limiting the achievable performance characteristics are described in Section 3.2, together with materials-related considerations. A discussion of how the system limitations are being addressed by different research groups is also provided. Section 3.3 provides a description of sample applications of transparent solar windows, showcasing an immediate application area of the harvested energy at the point of generation—inside the window structure itself where active control over transparency is possible. Other application areas are also mentioned, together with a brief discussion of significant recent achievements in semitransparent organics-based solar cell materials. This review focuses mainly on the developments in three principal technology categories (regular BIPV, non-concentrating semi-transparent BIPV, and LSC-type devices), illustrating the recent history and evolution of unconventional photovoltaics, developing towards systems with increasing power conversion efficiency simultaneously with improving control over the system appearance, architectural deployment suitability, product lifetime, and application readiness.

2. Main Technologies for Integrating Energy Harvesting Surfaces into Buildings

Expansion of the potential deployment areas for the traditional (non-transparent) PV modules started with the use of building façade and wall surfaces. This was likely due to both the ready availability of these additional energy-harvesting areas, and also because of the relative scarcity of the optimally-tilted roof-based PV placement options, especially in multi-storey urban environments. Additional efforts aimed at further expanding the surface areas suitable for “solarisation” included the placement of PV modules in somewhat unexpected locations, e.g., under road pavements [49]. Even though both the horizontal and the vertical module orientations are not optimally tilted with respect to the incoming sunlight, vast potential deployment areas become available using these approaches. The placement geometry of these non-conventional energy harvesting surfaces can be customised in a site-specific manner to maximise the energy production efficiency in most locations, by accounting for local environment-specific variables, such as the prevailing sun azimuth direction during the summer months and external shading conditions. Considering the sun altitude angle corresponding to the standardised peak irradiation conditions (AM1.5G spectral distribution at 1000 W/m2), both the horizontal and the sun-facing vertical PV surfaces intercept about 700 W of the total (direct-beam and diffused) solar irradiation flux per 1 m2 of active area at peak weather conditions. The azimuth-optimised vertical placement of PV surfaces can be more suitable for maximizing the yearly energy output per building footprint area (compared to the horizontal orientation), at least for urban locations in moderate latitudes. This is because of factors, such as the accumulation rates of surface contaminants, wind-assisted cooling effects, sun altitude angles being well away from zenith for most of the day, and the ground albedo or building-wall reflections, which provide an additional diffused radiation background easily interceptible by the wall-mounted PV. At the same time, the overall architectural design of buildings should ideally account for the site-specific and climate-specific energy-harvesting performance optimisation of wall-mounted PV arrays or windows, for example, by installing these systems on one or two of the most suitable building walls only. Figure 2 provides a system-level graphical outlook and main performance comparisons for most of the BIPV technology types commercialised so far.

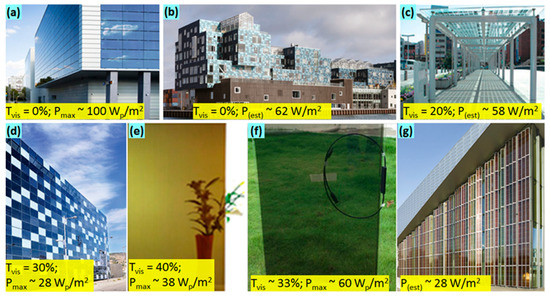

Figure 2.

Conventional (building-applied photovoltaics (BAPV)), colour-optimised, and semitransparent commercially available BIPV technologies at a glance. (a) Avancis PowerMax Skala CuInSe2 panels [50]; (b) Multilayer-coated, colour-optimised BIPV facade by EPFL (Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne, Switzerland) and Emirates Insolaire [27,28,33]; (c) AGC (Asahi Glass Corporation, Japan) Sunjoule product [51]; (d) Onyx Solar a-Si high-transparency BIPV panels [52]; (e) Hanergy BIPV panels using a-Si [53]; (f) High-transparency CdTe BIPV panels [35]; (g) Solaronix BIPV façade based on semi-transparent dye-sensitised solar cells [34,54]; the methodology used for making the estimates of electric output is described in [55].

The average transparency-related and energy-related figures of performance shown within insets in Figure 2 have either been estimated from the published data, or taken from the relevant product specifications. The standardised peak-rated electric power outputs per unit active PV area, shown as Pmax or Wp/m2 data within parts of Figure 2, have been obtained from the published manufacturer’s specifications, in which the optimum (peak-output) geometric orientations and tilt angles were presumed, except for Figure 2a. The Pmax figure shown in Figure 2a was obtained from Avancis, Inc. published product specifications by also accounting for the vertical sun-facing panel orientation, using the flux reduction factor of 0.7. The estimated figures for the electric output per unit active area of custom-installed BIPV (Figure 2b,c,g) have been obtained using the published data for the yearly energy outputs, the total areas of installed PV, and the location-specific weather-dependent insolation data, using the methodology described in [55]. Therefore, these estimates of the maximum expected electric power output per unit active area are not standardised with respect to either the incident solar spectrum or cell surface temperatures.

A notable recent trend in BIPV has been the apparent “mimicry” capability of the solar cell surfaces covering building facades, assisted by the reflection colour-tuning multilayer thin-film coatings. Twelve thousand coloured solar panels have been installed at the Copenhagen International School’s new building (Figure 2b), completely covering the building and providing it with 300 MWh of electricity per year (and meeting over half of the school’s energy needs) [27,33]. These PV panels covered a total area of 6048 square meters, making it one of the largest BIPV installations in Denmark [28]. It is possible to derive a figure of performance of about 62 W/m2 for the maximum expected electric output generation capacity, by using these reported data on the predicted annual energy generation, the energy-converting area installed within the façade (6048 m2), and by approximating the other parameters (e.g., assuming the peak-equivalent sunshine-hours per sunny day at the installation location is around 4 h, and 200 sunny days per year). The annual number of sunny days is approximated here by using the figures from the average monthly distribution of rainy days for this location, which is accessible from a range of online weather-related data sources. The multilayer coatings, which provided the apparent colour adjustment by reflecting the blue-green parts of the spectrum, have, therefore, reduced the electric performance somewhat, compared to an optimally-oriented CuInSe2 (CIS) facade. However, this 62 W/m2 figure has been obtained from a real, feature-rich architectural installation in Northern Europe, in which a significant fraction of active PV area has not been oriented optimally, and also experiences partial geometric shading. This shows the significant practical application potential of colour-adjusted BIPV technologies, at least, for the non-transparent installations. Similar performance in energy harvesting (~58 W/m2) has been estimated from a horizontally-mounted semitransparent BIPV using monocrystalline silicon cell technology ([51], Figure 2c), as well as documented in [35] (~60 Wp/m2) for a peak-oriented CdTe-based semitransparent (Tvis ~ 33%) non-concentrating BIPV module, likely from the product range of Xiamen Solar First Energy Technology Co., Ltd. (Xiamen, China)—judging by the close matching of the academically- and commercially-published electrical specifications ([35] vs. [56]).

It is interesting to compare the current energy-harvesting performance in the available semitransparent BIPV products with both the PV efficiency records achieved so far in small-size luminescent concentrators, and the theoretical limits of efficiency predicted for the highly-transparent concentrator-type BIPV, and also the transparent organic solar-cell modules. The current efficiency record for a 5 cm × 5 cm LSC using organic luminophores and edge-mounted GaAs cells stands at 7.1% [57], corresponding theoretically to 71 Wp/m2. However, the scaling of electric power output cannot be linear with increasing concentrator area, for multiple reasons including the relevant loss mechanisms [58], and other considerations related to the thermodynamics of light concentration and light transport phenomena, discussed in subsequent sections. The assessments of the performance limits in highly transparent area-distributed PV and also in concentrators have been made in [59] and in [55], pointing to a theoretical possibility of generating up to about 57 Wp/m2 in systems of 70% colour-unbiased transparency. This theory-limit performance was calculated presuming the use of CIS solar cells of wide spectral responsivity bandwidth, at 25 °C cell temperature, 12.2% PV module efficiency, for the peak geometric orientation and tilt of idealised concentrator panels (with AM1.5G, 1000 W/m2 irradiation.) The practically-achieved, literature-reported clear solar window performance in factory-assembled glass-based windows is now close to 50% of its theoretical limit [55]. At the same time, the best power conversion efficiency (PCE) reported recently in transparent organic photovoltaics was 9.77% at 32% transparency, according to [60]. The authors of [61] also reported achieving 4.00% PCE at 64% transparency in polymer solar cells produced by solution processing; other recently-demonstrated combinations of PCE and visible-range transparency in organic solar cells were summarised recently in [44]. To the best of our knowledge, no installation-ready or standards-compliant BIPV systems with academically published specifications and using transparent polymers-based solar cells (or transparent organic luminophores) are currently available on the market. Significant and ongoing product development efforts are being undertaken at Ubiquitous Energy (USA), aimed at commercialisation of transparent organics-based solar windows, with some groundbreaking material development results reported within supplemetary material dataset of [44], e.g., achieving PCE of 5.20% at Tvis = 52%.

Reports on the ready availability of any inorganic materials-based clear and highly transparent solar window, skylight, or curtain wall products are still very rare. Among these product types with published specifications and now available to the market are BAPV-type solar-powered skylights from Velux (Denmark) [62], and an emergent range of solar windows, curtain wall, and solar skylight products marketed by ClearVue Technologies (Perth, Australia), which have passed the various industry standard compliance tests in 2018. The relevant technical details and the performance-related description of ClearVue solar window prototypes are available from [55], and their core technology fundamentals and the history of development were reported in [19] and [20]. Other solar window manufacturers, e.g., Physee (The Netherlands) [63], or GlassToPower [64] do not appear to publish the technical details (in particular, PV current-voltage (I-V) curve datasets) related to their current product specifications.

Even though we are still at the very beginnings of the era marked by the widespread use of transparent (or clear) solar windows, the range and scale of their potential applications is recognised as enormous (summarised graphically in Figure 3.) The necessity of developing the new, windows-based distributed generation networks to future-proof the urban areas, power the Internet of Things (IOT) revolution, and reduce the reliance on fossil fuels has also been widely recognised [26]. This is further confirmed by the ongoing research, development, and investment momentum now continuing in this area and all related materials science areas worldwide [30,31,32,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48].

Figure 3.

Highly transparent solar windows and their application areas. The solar window prototypes shown installed into an off-grid bus stop in Melbourne (Australia) are described in [55]; other solar windows shown in the right-hand side of the image are current products from ClearVue Technologies, showcased at Greenbuild Expo in Chicago, USA, in November 2018.

The value of developing highly-transparent solar windows is related to multiple unique qualities these systems can bring about. Among these are the provision of high-quality views and natural daylighting options for building occupants, the potential for large reductions in lighting-related energy expenditures, and the optional ready availability of added active or passive control over the window features, such as apparent colours or the degree of visible transparency. These features will require adding custom-designed optical coatings or active transparency-control layers to the initially-transparent energy-generating window systems, to maximise the number of possible options for the product appearance modification. Other unique benefits of highly transparent solar windows will be best illustrated in emergent application areas, such as advanced sustainable greenhousing, where the plant growth processes require either plenty of natural visible light or the precise control over illumination spectra.

Due to the renewed attention to the next-generation photovoltaics now being paid by multiple research groups, public institutions, and private companies worldwide, it is currently widely expected that new types of technologies, functional materials, and products will continue to be developed. The next sections of the present review will focus in more technical detail on the major results and developments demonstrated in recent years in the areas related to both the direct area-based solar energy converters, and also the concentrator-type solar windows.

3. Principal Results in Semi-Transparent PV Module Development, New Materials for Solar Concentrators, and Current Trends in Transparent Energy Harvesters

Considering that a number of important developments have been demonstrated in recent years in all BIPV technologies, related functional materials, and solar energy harvesting approaches, it is logical to identify the two main technology-related device categories to be discussed separately: the area-based PV energy converters, and the concentrator-type PV energy-harvesting systems. Forward-looking technologies and advanced novel materials have been investigated actively during the recent decade, resulting in noteworthy prototype demonstrations and product-level systems development, across the entire spectrum of BIPV application types. The following subsections address the principal results demonstrated in the area of semi-transparent PV energy harvesters from all main technological categories.

3.1. Recent Developments in Semitransparent Non-Concentrating BIPV Technologies

Semitransparent non-concentrating BIPV technologies are defined not only by their degree of visible-range transparency but also by their capability of enabling immediate photovoltaic energy conversion process, localised at any arbitrary region of light-ray incidence onto their active device areas. On the other hand, in concentrator-type semitransparent PV, the PV conversion is engineered to typically take place at the active (non-transparent) solar-cell areas placed at (or near) the edges of light-capturing semitransparent or clear aperture areas. These aperture areas serve to re-direct the incident light rays towards PV cells, and may contain materials providing partial light-trapping functionality, and/or light-harvesting structures that assist waveguiding-type propagation. Therefore, the major defining difference between these two main device categories is in the light propagation path-length within the devices, between the points of ray incidence and the location(s) where the PV conversion takes place. Both technological approaches possess their unique advantages and disadvantages, which are related to how the fundamental problem of balancing the overall energy-conversion efficiency and the degree of device transparency is addressed. The common metrics-related parameters used to evaluate the performance of semitransparent non-concentrating PV (or their suitability for any particular application area) include the visible light transmission (VLT), and power conversion efficiency (PCE) at standard test conditions (STC). The STC in PV metrology refer to using the standardised solar spectrum for device irradiation (AM1.5G spectral distribution, with 1000 W/m2 in radiation flux density), and making PV current-voltage characteristic measurements whilst keeping the solar cell surface temperatures at 25 °C. If detailed PCE characterisation metrology results are not available, other published product specifications or performance-related data can often be used to derive or estimate the maximum output power rating per unit active area. Table 1 summarises the main performance parameters achieved using non-concentrating semitransparent PV technologies in recent years.

Table 1.

Performance summary (transparency, materials, and efficiency-related data) for main non-concentrating semi-transparent solar cell technologies and building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPV) products with significant visible transmission.

A number of industrialised, product-level semitransparent PV module manufacturing technologies have been established, based on patterning the non-transparent active PV material area to ensure transparency. Systems using either amorphous silicon or cadmium telluride are becoming increasingly common, even though their (spectrally averaged) visible-range light transmission does not exceed 40 to 50%. Up to date, none of the commercially available patterned-layer energy-generating modules employing inorganic PV materials feature colour-neutral clear appearance or uniform transmission characteristics across their aperture areas.

A notable current trend in semitransparent PV modules development is the continued (and growing) attention of multiple research groups worldwide dedicated to optimizing the perovskite-based material systems. This is due to the rapid progress demonstrated in the performance (PCE) of perovskite-based photovoltaics recently, and over a relatively short time scale, reaching 27.3% conversion efficiency record in (non-transparent) tandem-type perovskite-silicon solar cells in 2018 [72]. The recently-achieved record efficiency in perovskite-based solar cells is at 20.9% [73]. The PCE of other semi-transparent perovskite-based research samples is currently in excess of 20%, demonstrated in stability-enhanced systems, in which the titanium dioxide-based electron transport layer was replaced by tin oxide [71]. The operational lifetime of these perovskite-based cells reported at the end of 2018 is still on the scale of several months, rather than years, which places their commercialisation prospects within the scope of near-future years, rather than today. Due to the potentially vast future application areas of perovskite-based semitransparent BIPV, significant research efforts are continuing in the materials science areas related to optimizing the chemistry and module structure of perovskite-based devices, to ensure improved environmental stability and performance. Methylammonium lead iodide (MAPbI3) based perovskite systems were recently shown [74] to possess intrinsic environmental stability limitations due to chemical chain reactions involving iodine vapour. The authors of [74] also hold a view that it is imperative to develop other types of perovskite material systems to achieve long-term stable solar cells, and work in this area is also ongoing in multiple research groups. Notably, efforts aimed at reducing the perovskite toxicity caused by the presence of lead and also removing the hysteresis in current-voltage characteristics have been reported [75,76].

Another rapidly developing category of semitransparent BIPV technologies possessing strong potential for future applications uses polymer-based organic materials, which can provide remarkable visible transparency simultaneously with high power conversion efficiency [60,61,66]. In this area, efforts to up-scale the solar cell sample size and ensure the long-term environmentally stable operation and commercially-applicable system packaging are currently ongoing, with product-level devices widely expected to be demonstrated in the near future.

3.2. Progress in Semitransparent Concentrator-Type Solar Window Technologies

Most semitransparent concentrator-type solar window technologies developed so far rely on the continued advances in the field of luminescent solar concentrators, which are underpinned by the development of new luminescent material types. This is because the only long-range (in the absence of glass surface imperfections or strong scattering) photon transport mechanism suitable for trapping the incident light energy within transparent waveguides is total internal reflection (TIR), which itself is enabled by the random directional character of luminescent emissions. The internal structure of LSC-type devices has also undergone rapid development, relying on the advances in areas, such as application-specific thin-film coatings, spectrally-selective transparent diffractive optics [20,77], embedded Mie scattering media [19,78], or other components designed to stimulate partial light trapping within waveguide-type glazing systems. More recently, conventional (non-transparent) PV elements, e.g., silicon or copper indium-gallium selenide (CIGS) cell modules started to merge into the design structure of transparent window-type solar concentrators, blocking a small transparent area fraction, but boosting the electric output through both the direct incident light capture and also collecting a part of light travelling within the device [40,55,79,80,81]. Various performance metrics parameters have been introduced in the LSC field for characterizing the performance of concentrator-type PV devices of all configurations and types; the most important of which are the PCE, geometric gain (G)—the ratio of the total light collection aperture area to the area of edge-mounted PV cells, photon collection probability P represented by the ratio of device PCE to the nominal PCE of the solar cell modules used in the device, and the optical concentration factor Copt = G · P [82]. Another useful concentrator metrics parameter is optical power efficiency ηopt which is the ratio of the optical power received at the PV cell surfaces to the total optical power incident onto device aperture area. Table 2 summarises the main optical and electric performance metrics parameters demonstrated in either laboratory samples or product-level technologies using different concentrator-type semitransparent PV systems in the last decade.

Table 2.

Performance summary for main recently-reported concentrator-type semi-transparent luminescent solar concentrator (LSC) devices and solar window technologies.

The optical power efficiency of LSC, or other types of concentrating semi-transparent PV energy harvesters (which utilise physical mechanisms other than TIR-guided luminescence, e.g., diffractive optics), is itself a product of multiple efficiency factors, each relating to a particular physical process harnessed for re-routing the incident photons towards the solar cell surfaces. For “classical” luminescent concentrator systems, ηopt can be represented in terms of the contributions of all physical phenomena taking place within the concentrator volume, in the following way [37,38]:

where R is the reflectivity of the front surface of the luminescent waveguide; PTIR is the probability of total internal reflection governed by the difference between the refractive indices of waveguiding material and outside air; ηabs is the fraction of the incident solar energy absorbed by the luminophore(s); ηPLQY is the photoluminescence quantum yield of the luminophore(s) used; ηStokes is the efficiency factor characterizing the energy losses due to heat generation during the absorption and emission events (Stokes shift loss); ηhost is the transport efficiency of the waveguide; ηTIR is the reflection efficiency of the waveguide determined by the smoothness of the waveguide surface, and ηself is the transport efficiency of the waveguided photons related to re-absorption of the emitted photons by another luminescent centre. For glass-based waveguiding structures, and using a 4% figure for the front-side reflectivity, 75% for PTIR corresponding to the refractive index of glass being n = 1.5, and by simplifying all other efficiency factors to equal 0.9, an estimate of the practical upper limit of the optical efficiency ηopt can be made, which is about 38%. The formula relating the parameter PTIR to the refractive indices of a luminescent slab-type waveguide and its surrounding medium is available from multiple sources, e.g., [86]. Then, presuming 22% of optical-to-electric power conversion efficiency (if using monocrystalline Si cells), this upper limit for the total (device-level) LSC PCE can then be estimated to be near 8.4%. This simplified estimate of the upper limit of efficiency is unrelated to the idealised-case theory-limit calculations, but rather refers to what may be achieved in the near future, provided that luminescent materials and waveguiding structures are improving continually. This figure also relates to completely non-transparent LSC systems and will need to be reduced for all semitransparent systems, corresponding to the reduction in the incident optical power fraction being harvested. An excellent and detailed analysis of the theoretical performance limits applicable to semitransparent luminescent concentrator systems is available from [59]. In addition, PCE of near 2.5% demonstrated in a system of total (the sum of direct and diffused) visible-range transmission near 70% are shown in [55] to approach about 50% of the corresponding theory-limit system PCE, accounting for the degree of transparency and the type of solar cells used.

ηopt = (1 – R) · PTIR · ηabs · ηPLQY · ηStokes · ηhost · ηTIR · ηself,

Equation (1) provides a useful physics-based insight into how the achievable LSC system efficiencies can continue to be improved in the future, considering that a significant scope exists for engineering new application-specific luminescent materials, optical coatings, and the internal structure of concentrator waveguides. Of special importance is the photoluminescence quantum yield of luminophores, which can potentially approach 100% in organic dyes, or even (technically) exceed 100% in “quantum cutting” inorganic phosphor types, which can emit two photons at a lower energy after single higher-energy photon excitation events. Many materials from this category can also exhibit very large Stokes shift values, thus, practically eliminating the self-absorption losses. It was predicted by the authors of [87] in 2014, that inorganic nanocrystals with high Stokes’ shift and consequently low self-absorption cross section would be suitable candidates for use in highly efficient LSCs, provided that their quantum efficiency can be increased to values approaching that of dyes, which would then lead to device efficiency values beyond 10%. This prediction will likely soon be demonstrated, at least, in systems of low visible transparency, in small sample sizes, and using the record-efficiency GaAs, or multijunction record-performer cells.

Multiple developments in the materials science of advanced luminescent materials for LSC-type applications and solar window devices have been reported in the recent literature and reviews, e.g., [88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98]. The authors of [88] reviewed the current state of the field in luminescent nanomaterials for LSC, and graphically represent the photon collection mechanisms and the various loss effects as “photon destination map”, which illustrates through modelling that the “escape cone losses” related to multiple total internal reflections and the associated processes, can be as high as 42% in practice, in a system where theoretically-evaluated escape-cone loss would have been near 25%. The role of reabsorption in total photon energy losses is emphasised, thus, elucidating the need to design luminescent materials with minimised self-absorption.

At present, a strong research focus and momentum are directed towards the development of advanced semiconductor nanocrystals and quantum dot (QD) materials, to enable strong reductions in self-absorption losses simultaneously with improved absorption efficiency in the near-infrared range, and to ensure greater environmental stability and light-fastness of luminophores [83,84,88,89,90,91,92,93]. Some drawbacks of inorganic QDs are discussed in [91], in particular, their susceptibility to deactivation by oxygen, often small Stokes shifts, and limited quantum efficiency, together with toxicity due to using materials, such as lead or cadmium. Organic dyes from the BASF Lumogen (Ludwigshafen, Germany) product range are still the mainstream LSC materials [91], and efforts at optimizing their concentrations and mixes are ongoing [89].

Activities aimed at achieving greater light concentration efficiency in more transparent and, importantly, larger-scale LSC devices, are also ongoing [94,95,96,97]. The authors of [95] analysed the QD-based LSCs and their maximum attainable practical concentration limits, as well as system scalability-related issues. There is currently a renewed interest in the use of upconverter-type luminophores, which were recently demonstrated to assist obtaining improved concentrator efficiencies again, achieving ~27% in PCE improvement with upconverters of only ~4% quantum yield [98].

The benefits of adding photonic mirrors to LSC structure and their effects on the optical transport phenomena within concentrators are reported in [99]. Other groups also concentrate on the development of various types of backreflector coatings, including Lambertian backreflectors [100], to improve the device PCE through enhanced partial trapping of light. Reaching the effective optical concentration ratio as high as 1.29 is reported [100]. For practically all semi-transparent solar window designs, the presence of a spectrally-selective coating backreflector is essential, since these systems are limited by their design to converting only a part of the incident solar spectrum. Since the trade-off between transparency and efficiency is fundamental, all possible approaches to maximizing the optical efficiency and the total PCE must be explored, which places a special emphasis on the structure-related photon-deflecting components (e.g., diffractive elements), working in synergy with advanced luminescent materials.

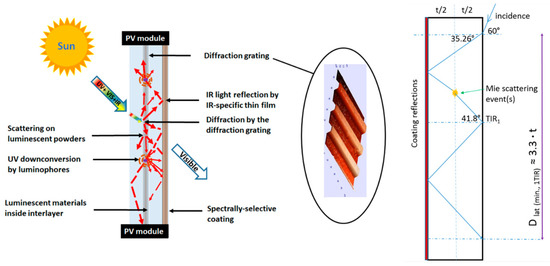

The application potential, role, and purpose of embedding the light-ray deflecting microstructures into LSC-type waveguides of solar windows are illustrated in Figure 4. Detailed analysis of the potential of diffractive and scattering optics for improving the photon collection probability at solar cells is reported in [20] and [77]. The roles of spectrally-selective backside-reflector coatings and especially the waveguiding panel thickness, in ensuring the capability of longer-range transport of the incident photons within waveguides, even in the presence of significant scattering, is also illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Semitransparent hybrid concentrator-type photovoltaic (PV) windows utilising physical mechanisms other than luminescence for inducing waveguiding-type propagation towards edge-mounted solar cells. The drawing on the right-hand side of the figure illustrates the minimum lateral displacement of photons incident at a 60° angle and travelling within a coating-assisted concentrator structure, after only a single total internal reflection (TIR) event, enabled by internal ray deflection. The minimum internal lateral displacement of partially-trapped photons incident at this angle is shown to be more than triple the system thickness dimension.

Diffractive grating-assisted ray deflection and Mie scattering processes at inorganic fluorescent pigment particles improve the probability of TIR events, thus, routing more photons towards solar cell surfaces. Highly transparent micro-scale diffraction gratings designed for use in solar windows have recently been reported [20].

Future improvements in the photon collection efficiency and total PCE of solar windows are expected to be demonstrated in systems using optimised combinations of advanced luminescent materials and device structures. In industrialisation-ready, large-area concentrator-type systems, the designs of new glazing system structures are expected to play a leading role, even regardless of the materials selection. This is because the photon management and partial light trapping mechanisms are related fundamentally to the device geometry and the limits imposed by thermodynamics. In particular, the minimum lateral displacement of an incident light ray inside a flat slab-type concentrator system scales in proportion with the device thickness (illustrated in Figure 4). Thermodynamics-based analysis of light propagation within generic non-imaging concentrator-type systems and the photon trapping-related metrics are reported in [101,102], using Fermat’s variational principle, which states that a ray of light propagates through an optical system in such a manner that the time required for it to travel from one point to another is minimised. This, together with the etendue conservation theorem [102] and the Yablonovitch limit [103], places fundamental limitations on the practically achievable light-trapping efficiencies in large-size LSC-like devices of all types. Other recently-reported important work on photon management in the presence of scattering processes [104] discloses an observation of the mean path length invariance for the photons propagating within arbitrary light-scattering media. The main finding reported was that, regardless of the location of the points of ray incidence, the system microstructure, or the angle of incidence, the mean photon propagation path-length inside the scattering medium is only governed by the system’s outer boundary’s geometry. This invariance imposes fundamental limitations on the internal path lengths achievable within any realistic LSC containing inorganic pigments and/or waveguide surface or volume structure imperfections. Parameters in the Equation (1), such as ηhost and ηTIR, are affected substantially by these waveguide imperfections, which are present invariably in realistic devices, especially in larger-scale concentrators containing multiple interfaces, where the internal propagation path lengths start to exceed the device thickness by several times for the majority of incident photons. A particularly important result reported in [104] in relation to the theoretically-evaluated system-invariant mean value of the internal photon propagation path-length (Stheor) in systems containing scattering centres (in a simplified case of a single glass-air interface) is described by

where V/Σ is the system’s volume-to-surface ratio, and n1 and n2 are the refractive indices of the outer and of the scattering regions, respectively. Therefore, in the case of rectangular slab-type waveguides representing the flat glass-based realistic inorganic pigment-containing LSC systems, this V/Σ ratio represents the system thickness, and the mean partially-trapped photon path-length is then within several times the thickness, regardless of the details of the internal microstructure. Notably, this mean internal path length invariance has been shown to apply also to the scattering process strength. Structured systems with multiple glass-air interfaces have been shown to provide mean photon path lengths somewhat in excess of that predicted by Equation (2), due to the increased probability of multiple internal reflections. Regardless of these fundamental limitations, collecting the photons efficiently at concentrator system edges, from the areas of incidence onto glass located within the range of several times the system thickness remains a valid option, which is demonstrated graphically in [77], in the presence of strong scattering at micron-scale luminophore pigment particles. The relevance of scattering as a short-range photon collection mechanism in LSC is also reported in [19,20] and discussed in [78,95].

<Stheor> = (4 · V/Σ) · (n22/n12)

The performance limits of luminescent solar concentrators with quantum dots in a selective-reflector-based optical cavity are evaluated in [105], where the dependency of the optical concentration on the geometric gain has also been studied. It has been reported that the best optical concentration factor performance is achievable in systems with a geometric gain of up to about 30, with further up-scaling of the device collection areas leading to diminishing returns in performance [105]. The analysis of optical losses in CuInS2-based nanocrystal LSC, in terms of balancing the absorption versus scattering, is reported in [106], where the estimates for the achievable optical efficiency are provided. Overall, the findings on efficiency limits and the limiting factors in LSC performance reported in multiple recent literature sources, in conjunction with the thermodynamic limitations applicable to solar concentrators, mean that further research efforts aimed at maximizing the photon collection probability over the areas of solar window aperture closest to the solar-cell locations are necessary.

3.3. Examples of Existing and Emergent High-Transparency PV Window Technologies and Their Applications

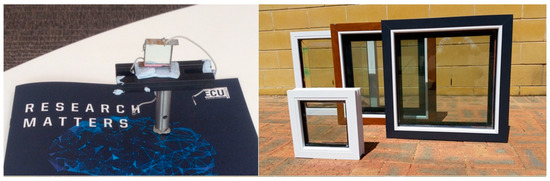

Novel applications of transparent solar windows continue to emerge and be proposed and demonstrated. High-transparency, long product life and application-ready glass-based solar windows are still quite rare and represent the future of solar window technologies. Among these application areas so far identified are the local use of the generated and/or stored renewable energy for powering lighting systems and/or advertising display devices [55], and active in-situ control over the transparency state of “smart” glazings described in a pioneering publication [107] back in 2010. Multiple implementations of “smart windows” have been demonstrated, e.g., using polymer-dispersed liquid–crystal (PDLC) [47,108,109,110], or electrochromic layer-based devices [111]. As soon as the highly-transparent energy-generating solar windows begin entering widespread commercial applications in buildings, it can be predicted that their first electric loads will often be transparency-control layers embedded into the same glazing systems. This is because of both the economics of re-designing the internal electric wiring circuits in buildings required to accommodate additional loads and the ready availability of PDLC products which can be laminated into the structure of current or emergent solar window glazing designs. For these reasons, even before wiring the internal lighting circuits in buildings to be powered by highly-transparent solar windows, it can be considered logical to use the generated energy immediately at the point of generation, actively controlling the window transparency state and demonstrating the expected significant cooling-related energy savings, at least in hot climates. Figure 5 shows the smart self-powered window early-prototype demonstration experiment from October 2014, in which a PDLC layer integrated (through a glass interlayer lamination process) into a 200 mm × 200 mm LSC panel was electrically driven using the window’s own electric output. The features of the electric power-generating system used in this smart window technology prototype have been disclosed in patent-related documentation [108], yet were not published academically to date.

Figure 5.

Transparency-controlled, self-powering PDLC-integrated “smart” solar window demonstration at Edith Cowan University (ECU) in October, 2014. A 200 mm × 200 mm hybrid concentrator-type solar window used four parallel-connected edge-mounted CuInSe2 modules of size 198 mm × 25 mm, the electric output of which was sufficient to control the embedded PDLC layer transparency within a broad transparency range [108].

Significant attention from multiple research groups has been directed towards the development and demonstration of multiple window-integrated active transparency control technologies during the recent years. Among these, notable developments took place recently in the area of incorporating the photothermally switchable perovskites into window glazings [112], potentially leading to achieving substantial energy savings in buildings due to the glass transparency responding to the surface temperature changes, simultaneously with the strong energy generation potential provided by perovskite-based solar cell systems. Thermochromic and also dichroic materials-based approaches to controlling the glazing system transparency and/or apparent colour in response to illumination level changes are also gaining momentum, as well as the emergent field of smart windows overall [113,114,115,116].

It has been demonstrated ([47], and also in the Supplementary Video section of this present article) that multiple series-connected inductive loads, such as DC motor-driven ventilation fans, can be powered by a single moderate-area (500 mm × 500 mm) highly transparent solar window device, at a sufficiently fast blade rotation rate to generate audible noise heard from some distance away. Whilst the power generated in small-area clear solar windows can be very moderate (several Watts per 500 mm × 500 mm sample using edge-mounted PV cells only), there is ready availability for their practical applications and use, e.g., for charging mobile devices. Figure 6 shows a graphical summary of prototype solar window development history at ECU, Perth, Western Australia, from an early (2011) high-transparency heat mirror-coated 2 cm × 2 cm × 0.6 cm sample with stripe-shape monocrystalline cut-outs from a Si cell attached to glass edges, to more advanced and up-scaled window systems developed between 2014 and 2016. Multiple design features and characterisation results relevant to these solar window types are first reported in [20].

Figure 6.

Solar window prototypes developed at Edith Cowan University (ECU between 2011–2016).

The earliest (2011) all-inorganic high-transparency (>90%) LSC prototypes integrated with Si cells (Figure 6, top left) used a single luminophore-loaded 0.5 mm interlayer connecting two 3 mm-thick quartz plates. One of these plates was coated by a spectrally-selective multilayer optical coating which reflected practically all solar near-IR light at wavelengths above 720 nm. The visible red colouration over the bottom-side solar cell surface was due to this coating reflecting a part of the visible far-red spectrum towards the cell. This small-area pre-prototype solar window sample is likely among the world’s most highly-transparent energy-generating structures built using only inorganic functional materials. Later transparent solar window prototypes developed at ECU in subsequent years used various solar cell configurations and types, as well as internal micro- and macrostructures for improving the photon collection probability at solar cell surfaces, some of which are yet unpublished.

An area of organic materials-based BIPV and transparent solar windows development is undergoing rapid development currently, and new performance records are being demonstrated continually in the power conversion efficiency, thus, offering a potentially strong competition to inorganics-based concentrator-type devices and other semitransparent BIPV. Very recently, a new efficiency record was demonstrated (PCE up to 12.25%, in small-area devices), achieved by tuning the chemical structure of organic photoactive materials. This is the highest certified efficiency of organic solar cells reported to date [117,118]. However, the degree of device transparency has not been explicitly specified. It is widely expected that the optical transparency, sample size, and environmental stability properties in transparent organic cells and future BIPV systems will continue to show improvements.

In the application areas related to moving the solar window technologies from labs to markets, significant challenges still exist, regardless of the core technology platform choice, or the type of functional materials employed. This is due to the necessity of bridging multiple industry-standards-related system requirements originating from different industries. These stringent requirements range from the decades-long product lifetimes often needed, to the ability of future solar windows to resist factors, such as wind loads, water penetration, and internal condensation events. At the same time, product compliance with stringent electric wiring rules, safety-related requirements, and building construction codes are also required.

Multiple independent building-scale trials of different transparent solar window technologies are yet to be conducted to identify their application suitability in various climates and installation-area footprints, as well as the economic potential. Nevertheless, it is becoming increasingly clear, from the present-day viewpoint, that future installations of the numerous types of emergent BIPV and BAPV technologies will be numerous. This is because the benefits of the large-scale and distributed generation of energy at the locations of end use are extensive, including the capability of providing blackout resistance in city buildings and the exclusion of significant transmission-line losses. The growing field of the Internet of Things and future expected widespread application of smart interconnected (5G) devices present demanding energy use requirements, which can be addressed by widespread BIPV generation.

4. Conclusions and Outlook

The practical integration of advanced solar energy-harvesting technologies into various elements of urban landscapes, including building windows, is rapidly becoming a mainstream trend. Substantial advances have been reported in recent years both in laboratory trials, and also in commercial demonstrations of the various semi-transparent solar cell types and solar window devices. A wide range of established semi-transparent PV and BIPV technologies exists currently, providing architects and building designers with multiple choices regarding the balance between the system aesthetics, degree of transparency (or colouration type), and power generating capacity. Multiple next-generation transparent solar-cell technologies, including dye-sensitised solar cells, patterned solar panels, organic polymer-based, and perovskite-based systems remain in active stages of development and continue to demonstrate new milestones in efficiency. Highly transparent, and colour-unbiased concentrator-type solar window systems are only beginning to make their entry into industry-wide acceptance. They now provide a previously unavailable combination of up to 70% in total visible light transmission and power conversion efficiency near 2.5%, based on systems demonstrated in 2017.

Despite the fundamental trade-offs between the required control over the visual appearance, degree of transparency, and the power generating capacity intrinsic to the design of advanced BIPV, their strong potential for transforming urban landscapes and providing substantial distributed generation capacity is certain. Developments in the materials science of advanced luminophores, coupled with novel designs of LSC-type semitransparent concentrator structures add continually to the possibilities of obtaining increased power conversion efficiencies. At the same time, a substantial energy-saving potential exists, provided by solar windows, which can also control the solar heat gain in buildings and the associated thermal insulation properties. The new trends in the local utilisation of the energy generated in the distributed way by the building components include using advanced windows with active transparency control, which can contribute substantially to both personnel comfort and climate control-related energy savings. It is currently expected that multiple commercial building-based trials of the latest transparent BIPV technologies will soon be conducted, uncovering their true practical applications potential.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1073/12/6/1080/s1, Video S1: ECU-ClearVue power generating window prototypes 2016.mp4.

Author Contributions

All authors (M.V., M.N.A. and K.A.) have contributed to the conceptualisation of this review article and data collection; M.V. analysed the data and prepared the manuscript; all authors discussed the data, graphics, and the presentation; M.N.A. contributed substantially to the data curation and the original draft preparation; M.V. and K.A. further reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Australian Research Council (grants LP130100130 and LP160101589) and Edith Cowan University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Capuano, L. International Energy Outlook 2018 (IEO2018); US Energy Information Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, S.; Majumdar, A. Opportunities and challenges for a sustainable energy future. Nature 2012, 488, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffert, M.I.; Caldeira, K.; Benford, G.; Criswell, D.R.; Green, C.; Herzog, H.; Jain, A.K.; Kheshgi, H.S.; Lackner, K.S.; Lewis, J.S.; et al. Advanced technology paths to global climate stability: Energy for a greenhouse planet. Science 2002, 298, 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poizot, P.; Dolhem, F. Clean energy new deal for a sustainable world: From non-CO2 generating energy sources to greener electrochemical storage devices. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 2003–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Xilei, D.; Liu, J. Building energy-consumption status worldwide and the state-of-the-art technologies for zero-energy buildings during the past decade. Energy Build. 2016, 128, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellnhuber, H.J.; van der Hoeven, M.; Bastioli, C.; Ekins, P.; Jaczewska, B.; Kux, B.; Thimann, C.; Tubiana, L.; Wanngård, K.; Slob, A.; et al. Final Report of the High-Level Panel of the European Decarbonisation Pathways Initiative; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; ISBN 978-92-79-96827-3. [Google Scholar]

- Long, L.; Ye, H. How to be smart and energy efficient: A general discussion on thermochromic windows. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Luo, H.; Zhang, Z.; Kang, L.; Chen, Z.; Du, J.; Kanehira, M.; Cao, C. Nanoceramic VO2 thermochromic smart glass: A review on progress in solution processing. Nano Energy 2012, 1, 221–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llordes, A.; Garcia, G.; Gazquez, J.; Milliron, D.J. Tunable near-infrared and visible-light transmittance in nanocrystal-in-glass composites. Nature 2013, 500, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, A.P.; Anoma, M.A.; Zhu, L.; Rephaeli, E.; Fan, S. Passive radiative cooling below ambient air temperature under direct sunlight. Nature 2014, 515, 540–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Yang, J.; Su, Y.S.; Du, W.; Ma, Y.G. Daytime passive radiative cooler using porous alumina. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2019, 191, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Yu, L.; Jiao, Z.; Xie, H.; Lou, X.W.; Sun, X.W. A bi-functional device for self-powered electrochromic window and self-rechargeable transparent battery applications. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, M.; Kong, L.; Long, Y.; Jiang, X.; Yu, A. Recent progress in VO2 smart coatings: Strategies to improve the thermochromic properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2016, 81, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torcellini, P.; Pless, S.; Deru, M.; Crawley, D. Zero Energy Buildings: A Critical Look at the Definition; National Renewable Energy Laboratory and Department of Energy: Golden, CO, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Groth, R.; Reichelt, W. Gold coated glass in the building industry. Gold Bull. 1974, 7, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampert, C.M. Heat mirror coatings for energy conserving windows. Sol. Energy Mater. 1981, 6, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalapati, G.K.; Kushwaha, A.K.; Sharma, M.; Suresh, V.; Shannigrahi, S.; Zhuk, S.; Masudy-Panah, S. Transparent heat regulating (THR) materials and coatings for energy saving window applications: Impact of materials design, micro-structural, and interface quality on the THR performance. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 95, 42–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, S.D.; Shannigrahi, S.; Ramakrishna, S. A review of conventional, advanced, and smart glazing technologies and materials for improving indoor environment. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2017, 159, 26–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamedi, R.; Vasiliev, M.; Nur-E-Alam, M.; Alameh, K. Spectrally-Selective All-Inorganic Scattering Luminophores For Solar Energy-Harvesting Clear Glass Windows. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliev, M.; Alghamedi, R.; Nur-E-Alam, M.; Alameh, K. Photonic microstructures for energy-generating clear glass and net-zero energy buildings. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, V.; Vasiliev, M.; Alameh, K. A Spectrally Selective Luminescence Concentrator Panel with a Photovoltaic Cell. EP Patent 2 726 920 B1, 23 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jelle, B.P.; Breivik, C. The path to the building integrated photovoltaics of tomorrow. Energy Procedia 2012, 20, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debbarma, M.; Sudhakar, K.; Baredar, P. Comparison of BIPV and BIPVT: A review. Resour.-Effic. Technol. 2017, 3, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biyik, E.; Araz, M.; Hepbasli, A.; Shahrestani, M.; Yao, R.; Shao, L.; Essah, E.; Oliveira, A.C.; del Caño, T.; Rico, E.; et al. A key review of building integrated photovoltaic (BIPV) systems. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2017, 20, 833–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, M.; Sadhu, P.K.; Panda, S.K. A critical review on building integrated photovoltaic products and their applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 61, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extance, A. The Dawn of Solar Windows, IEEE Spectrum 2018. Online Publication. Available online: https://spectrum.ieee.org/energy/renewables/the-dawn-of-solar-windows (accessed on 10 February 2018).

- International Energy Agency—Photovoltaic Power Systems Programme Annual Report 2016. Available online: https://docplayer.net/52701446-P-h-o-t-o-v-o-l-t-a-i-c-p-o-w-e-r-s-y-s-t-e-m-s-p-r-o-g-r-a-m-m-e-annual-report.html (accessed on 26 November 2018).

- Building Integrated Photovoltaics: Product Overview for Solar Building Skins, Status Report 2017. Available online: https://www.seac.cc/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/171102_SUPSI_BIPV.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2018).

- Attoye, D.E.; Aoul, K.A.T.; Hassan, A. A Review on Building Integrated Photovoltaic Façade Customization Potentials. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornaro, C.; Basciano, G.; Puggioni, V.A.; Pierro, M. Energy Saving Assessment of Semi-Transparent Photovoltaic Modules Integrated into NZEB. Buildings 2017, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.H.; Choi, S.-H. Recent Studies of Semitransparent Solar Cells. Coatings 2018, 8, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-T.; Guo, L.J.; Park, H.J. Neutral- and Multi-Colored Semitransparent Perovskite Solar Cells. Molecules 2016, 21, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The School with the Largest Solar Facade in the World. Available online: https://phys.org/news/2017-02-school-largest-solar-facade-world.html (accessed on 26 November 2018).

- Massive Solar Façade for Swiss Convention Centre. Available online: https://www.forumforthefuture.org/greenfutures/articles/massive-solar-façade-swiss-convention-centre (accessed on 2 May 2018).

- Barman, S.; Chowdhury, A.; Mathur, S.; Mathur, J. Assessment of the efficiency of window integrated CdTe based semitransparent photovoltaic module. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 37, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, W.H.; Lambe, J. Luminescent greenhouse collector for solar radiation. Appl. Opt. 1976, 15, 2299–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetzberger, A.; Greube, W. Solar-energy conversion with fluorescent collectors. Appl. Phys. 1977, 14, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debije, M.G.; Verbunt, P.P.C. Thirty Years of Luminescent Solar Concentrator Research: Solar Energy for the Built Environment. Adv. Energy Mater. 2012, 2, 12–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzaro, R.; Vomiero, A. The Renaissance of Luminescent Solar Concentrators: The Role of Inorganic Nanomaterials. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1801903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinders, A.; Kishore, R.; Slooff, L.; Eggink, W. Luminescent solar concentrator photovoltaic designs. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 57, 08RD10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinardi, F.; Colombo, A.; Velizhanin, K.A.; Simonutti, R.; Lorenzon, M.; Beverina, L.; Viswanatha, R.; Klimov, V.I.; Brovelli, S. Large-area luminescent solar concentrators based on ‘Stokes-shift-engineered’ nanocrystals in a mass-polymerized PMMA matrix. Nat. Photonics 2014, 8, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergren, M.R.; Makarov, N.S.; Ramasamy, K.; Jackson, A.; Guglielmetti, R.; McDaniel, H. High-Performance CuInS2 Quantum Dot Laminated Glass Luminescent Solar Concentrators for Windows. ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Meek, G.A.; Levine, B.G.; Lunt, R.R. Near-Infrared Harvesting Transparent Luminescent Solar Concentrators. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2014, 2, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traverse, C.J.; Pandey, R.; Barr, M.C.; Lunt, R.R. Emergence of highly transparent photovoltaics for distributed applications. Nat. Energy 2017, 2, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, F. Organics: Materials and Energy. In World Scientific Handbook of Organic Optoelectronic Devices; Transparent Photovoltaics; World Scientific: Singapore, 2018; Chapter 11; pp. 445–499. [Google Scholar]

- Husain, A.A.F.; Hasan, W.Z.W.; Shafie, S.; Hamidon, M.N.; Pandey, S.S. A review of transparent solar photovoltaic technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 94, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalapati, G.K.; Sharma, M. Heat Regulating Materials for Energy Savings and Generation: Materials Design, Process and Implementation; CWP Publishing: Orange, Australia, 2019; Available online: https://centralwestpublishing.com/specialty-materials/ (accessed on 19 March 2019).

- Gates, B. Energy Innovation—Why We Need It and How to Get It. Published by Breakthrough Energy Coalition. 2015. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjQjvmfiaPeAhVWdCsKHVsMCbQQFjAAegQICRAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.gatesnotes.com%2F~%2Fmedia%2FFiles%2FEnergy%2FEnergy_Innovation_Nov_30_2015.pdf%3Fla%3Den&usg=AOvVaw1VZwJaefqQT1p4Qrm-UzYm (accessed on 19 March 2019).

- Ryan, D. Solar Panels Replaced Tarmac on a Motorway—Here Are the Results. 2018. Available online: https://phys.org/news/2018-09-solar-panels-tarmac-motorwayhere-results.html (accessed on 6 December 2018).

- Avancis PowerMax Skala Datasheet. Available online: https://www.avancis.de/en/products/powermaxr-skala-40/ (accessed on 5 December 2018).

- Sunjoule Product Brochure by Asahi Glass Corp. p. 11. Available online: http://www.agc-solar.com/agc-solar-products/bipv.html (accessed on 5 December 2018).

- Onyx Solar Amorphous Silicon PV Glass Specifications—High Transparency. Available online: https://www.onyxsolar.com/product-services/technical-specifications (accessed on 5 December 2018).

- Hanergy Product Manual 141129 Section 1.3.1 (2018). p. 11. Available online: https://www.slideshare.net/RonaldKranenberg/hanergyproductbrochure141129 (accessed on 5 December 2018).

- Solaronix Solar Cells Brochure. Available online: http://solaronix.com/solarcells/ (accessed on 11 December 2018).

- Vasiliev, M.; Alameh, K.; Nur-E-Alam, M. Spectrally-Selective Energy-Harvesting Solar Windows for Public Infrastructure Applications. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CdTe-Based Semitransparent BIPV Products from Xiamen Solar First Energy Technology Co., Ltd. Available online: https://www.alibaba.com/product-detail/High-Transparent-Asi-frameless-CdTe-48W_60541808069.html (accessed on 11 December 2018).

- Slooff, L.H.; Bende, E.E.; Burgers, A.R.; Budel, T.; Pravettoni, M.; Kenny, R.P.; Dunlop, E.D.; Büchtemann, A. A luminescent solar concentrator with 7.1% power conversion efficiency. Phys. Status Solidi (RRL) 2008, 2, 257–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummeltshammer, C.; Taylor, A.; Kenyon, A.J.; Papakonstantinou, I. Losses in luminescent solar concentrators unveiled. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2016, 144, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Lunt, R.R. Limits of visibly transparent luminescent solar concentrators. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2017, 5, 1600851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yan, C.; Lau, T.-K.; Wang, J.; Liu, K.; Fan, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhan, X. Fused Hexacyclic Nonfullerene Acceptor with Strong Near-Infrared Absorption for Semitransparent Organic Solar Cells with 9.77% Efficiency. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1701308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.-C.; Dou, L.; Zhu, R.; Chung, C.-H.; Song, T.-B.; Zheng, Y.B.; Hawks, S.; Li, G.; Weiss, P.S.; Yang, Y. Visibly Transparent Polymer Solar Cells Produced by Solution Processing. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 7185–7190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VELUX Solar Powered Skylight (VSS). Available online: https://www.velux.com.au/products/skylights/vss%20solar%20skylight (accessed on 19 March 2019).

- Physee PowerWindow Products. Available online: https://www.physee.eu/products (accessed on 11 December 2018).

- GlassToPower Technology Description. Available online: http://www.glasstopower.com/la-tecnologia-en/ (accessed on 12 December 2018).

- Ito, S.; Chen, P.; Comte, P.; Nazeeruddin, M.K.; Liska, P.; Péchy, P.; Grätzel, M. Fabrication of Screen-Printing Pastes from TiO2 Powders for Dye-Sensitised Solar Cells. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2007, 15, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunt, R.R.; Bulovic, V. Transparent, near-infrared organic photovoltaic solar cells for window and energy-scavenging applications. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 98, 113305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailie, C.D.; Christoforo, M.G.; Mailoa, J.P.; Bowring, A.R.; Unger, E.L.; Nguyen, W.H.; Burschka, J.; Pellet, N.; Lee, J.Z.; Grätzel, M.; et al. Semi-transparent perovskite solar cells for tandems with silicon and CIGS. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 956–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldán-Carmona, C.; Malinkiewicz, O.; Betancur, R.; Longo, G.; Momblona, C.; Jaramillo, F.; Camacho, L.; Bolink, H.J. High efficiency single-junction semitransparent perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 2968–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hägglund, C.; Johansson, M.B.; Sveinbjörnsson, K.; Johansson, E.M.J. Fine Tuned Nanolayered Metal/Metal Oxide Electrode for Semitransparent Colloidal Quantum Dot Solar Cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 1921–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polysolar BIPV Solar Glass Specifications. Available online: http://www.polysolar.co.uk/Technology/PS-CT (accessed on 14 December 2018).

- Qiu, L.; Liu, Z.; Ono, L.K.; Jiang, Y.; Son, D.-Y.; Hawash, Z.; He, S.; Qi, Y. Scalable Fabrication of Stable High Efficiency Perovskite Solar Cells and Modules Utilizing Room Temperature Sputtered SnO2 Electron Transport Layer. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 1806779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford PV Sets World Record for Perovskite Solar Cell. Available online: https://www.oxfordpv.com/news/oxford-pv-sets-world-record-perovskite-solar-cell (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- Researchers Show World-Record 20.9% Perovskite Cell, New SSG Process Increasing Stability. Available online: https://www.pv-magazine.com/2018/07/05/researchers-show-world-record-20-9-perovskite-cell-new-ssg-process-increasing-stability/ (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- Wang, S.; Jiang, Y.; Juarez-Perez, E.-J.; Ono, L.K.; Qi, Y. Accelerated degradation of methylammonium lead iodide perovskites induced by exposure to iodine vapour. Nat. Energy 2016, 2, 16195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimanioun, N.; Rani, M.; Sharma, S.; Kumar, A.; Tripathi, S.K. Binary metal zinc-lead perovskite built-in air ambient: Towards lead-less and stable perovskite materials. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2019, 191, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Hu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Sheng, C. Methylammonium acetate as an additive to improve performance and eliminate J-V hysteresis in 2D homologous organic-inorganic perovskite solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2019, 191, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliev, M.; Alameh, K.; Badshah, M.A.; Kim, S.-M.; Nur-E-Alam, M. Semi-Transparent Energy-Harvesting Solar Concentrator Windows Employing Infrared Transmission-Enhanced Glass and Large-Area Microstructured Diffractive Elements. Photonics 2018, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, S.; Chen, W.; Wang, D.; Li, C.; Wu, D.; Hao, J.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, K. Scattering enhanced quantum dots based luminescent solar concentrators by silica microparticles. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2018, 179, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leow, S.W.; Corrado, C.; Osborn, M.; Isaacson, M.; Alers, G.; Carter, S.A. Analyzing luminescent solar concentrators with front-facing photovoltaic cells using weighted Monte Carlo ray tracing. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 113, 214510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, C.; Leow, S.W.; Osborn, M.; Carbone, I.; Hellier, K.; Short, M.; Alers, G.; Carter, S.A. Power generation study of luminescent solar concentrator greenhouse. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2016, 8, 043502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinders, A.; Debije, M.G.; Rosemann, A. Measured Efficiency of a Luminescent Solar Concentrator PV Module Called Leaf Roof. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2017, 7, 1663–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmet, L.; Ras, A.J.M.; de Boer, D.K.G.; Debije, M.G. Monocrystalline silicon photovoltaic luminescent solar concentrator with 4.2% power conversion efficiency. Opt. Lett. 2012, 37, 3087–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.; Li, H.; Klimov, V.I. Tandem luminescent solar concentrators based on engineered quantum dots. Nat. Photonics 2018, 12, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinardi, F.; Ehrenberg, S.; Dhamo, L.; Carulli, F.; Mauri, M.; Bruni, F.; Simonutti, R.; Kortshagen, U.; Brovelli, S. Highly efficient luminescent solar concentrators based on earth-abundant indirect-bandgap silicon quantum dots. Nat. Photonics 2017, 11, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aste, N.; Tagliabue, L.C.; Del Pero, C.; Testa, D.; Fusco, R. Performance analysis of a large-area luminescent solar concentrator module. Renew. Energy 2015, 76, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Yao, Y.; Bronstein, N.D.; Li, L.; Alivisatos, A.P.; Nuzzo, R.G. Enhanced Photon Collection in Luminescent Solar Concentrators with Distributed Bragg Reflectors. ACS Photonics 2016, 3, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Sark, W.G.J.H.M. Will luminescent solar concentrators surpass the 10% device efficiency limit? SPIE Newsroom 2014, 9178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraitisa, P.; Schroppb, R.E.I.; van Sark, W.G.J.H.M. Nanoparticles for Luminescent Solar Concentrators—A review. Opt. Mater. 2018, 84, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]