Abstract

In the present study, the expansion characteristics of plant chemical alcohol waste liquid were experimentally studied with a vertical tube furnace system. The results showed that the droplet quality, heating temperature, and atmosphere directly influenced the droplet expansion. The droplet mass had nothing to do with the swelling volume index (SVI) but had a significant influence on the expansion time, with a larger droplet mass and longer expansion time. The heating temperature had a significant influence on the expansion characteristics of the waste liquid. As the heating temperature increased, the droplet SVI became larger with a shorter expansion time. The nitrogen atmosphere was more conducive to droplet volume expansion than the air atmosphere but had less of an effect on the expansion time. The volume of waste liquid droplets expanded more than 5 times, forming an internal porous structure, thereby increasing the comparative area and the probability of contact with oxygen to facilitate the combustion of the waste liquid.

1. Introduction

Renewable resources have the properties of regeneration in a short time, the ability to be reused and recycled, and little secondary pollution to the environment as they do not increase emission of greenhouse gases. These qualities have attracted increasingly more attention [1]. Biomass is a very important category among renewable resources and can be used to produce chemical products and replace petroleum refinery products. How to obtain energy, resources, and materials from biomass has become the focus of current research [2,3,4]. Countries around the world are actively exploring and studying the use of biological resources to replace fossil resources to produce plant-based chemical products and raw materials [5,6].

Among various biomass resources, corn, as one of the main food crops, is widely planted on a large scale. Many studies and experiments of technology that uses corn and corn straw for the biorefining of polyols have been carried out and employed in industrial applications. The development of plant chemical alcohol technology has positive practical and social significance for the current shortage of oil resources, environmental pollution, and other problems that have a profound impact on sustainable economic development and construction of the ecological environment [7].

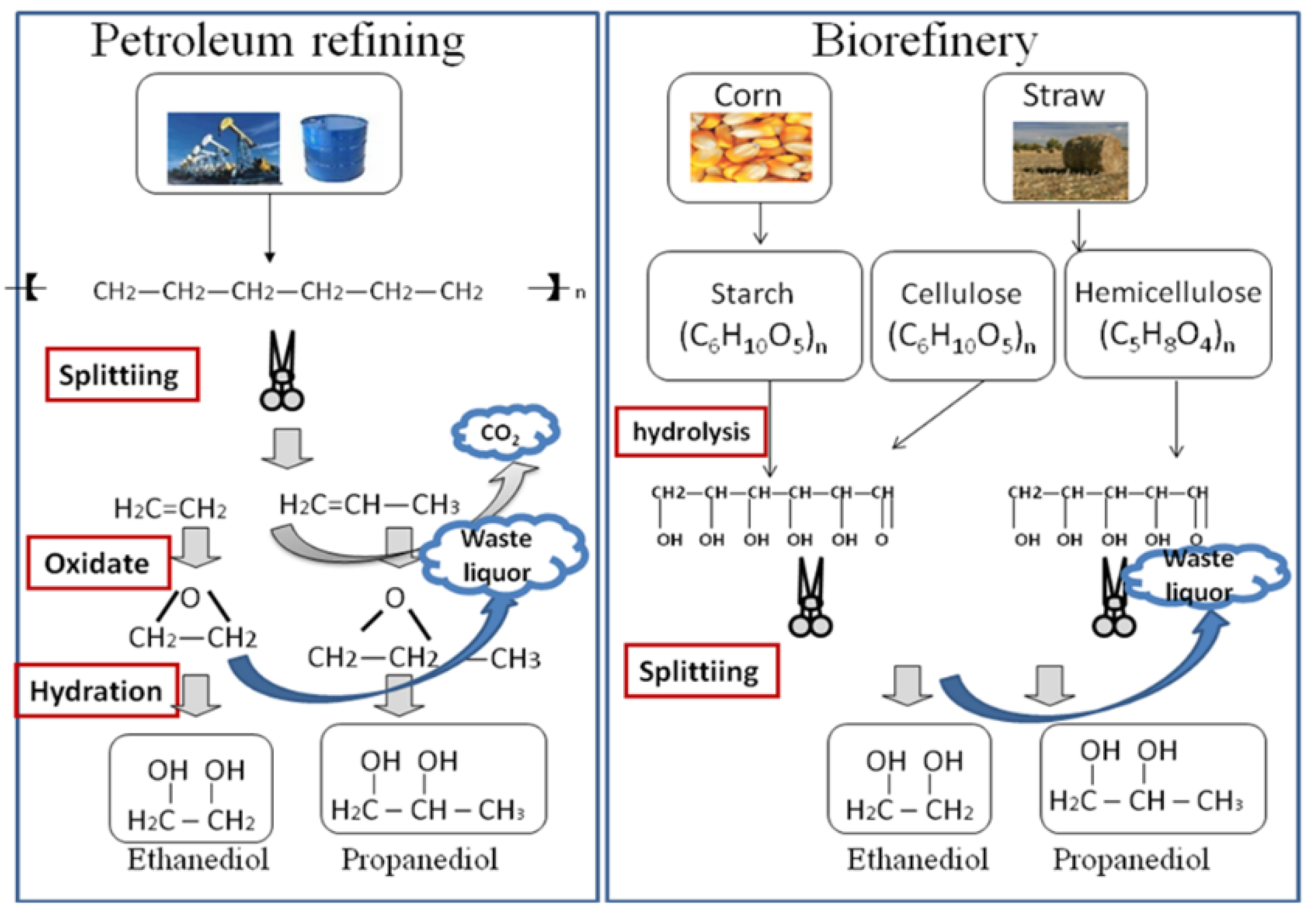

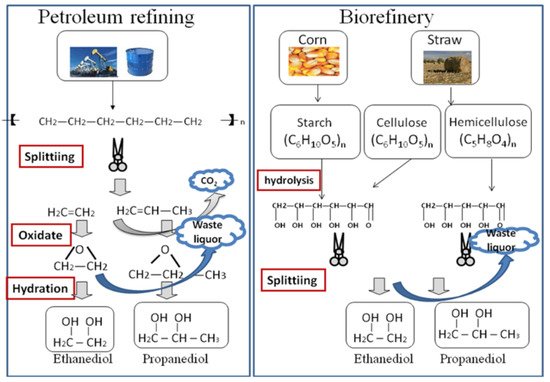

Figure 1 illustrates the process of petroleum refining and biorefining to produce polyols. Table 1 illustrates the CO2 emission data for 1 t ethanediol production. Comparing Figure 1 and Table 1, it can be seen that biorefining has the obvious advantage of low emission as the CO2 emission of 1 t ethanediol produced by biorefining decreases by 51.7%. At least 1.42 t corn is needed to produce 1 t ethanediol. The corn absorbs 4.54 t CO2 in the growth process and discharges 2.55 t CO2 in the biorefining process, so the emission of CO2 can decrease by 1.99 t from corn to ethanediol.

Figure 1.

Petroleum refining and biorefining to produce polyols.

Table 1.

CO2 emission data of 1 t ethanediol production.

As corn straws produce chemical alcohol through a biorefinery, the raw material is sent into the production equipment, where the chemical reacts with alkali elements and other chemical reagents under a certain pressure and temperature (with some catalysts). Then, diversified chemical alcohol (ethanediol, propylene glycol, butyl glycol, etc.) is separated by a special process [8,9]. A great deal of waste liquor is produced during the production of plant chemical alcohol; in a plant chemical alcohol factory with an output of 200,000 t/y, about 7 t/h of waste liquor is produced. If this much waste liquor cannot be timely and effectively handled, it will produce serious pollution in the natural environment. The need to treat waste liquor without pollution has become a major restricting factor in the development of the plant chemical alcohol industry.

As a by-product of alcohol production, the waste liquor of plant chemical alcohol becomes paste at room temperature. With an increase in temperature, the viscosity decreases quickly. When the waste liquor is heated to above 100 °C, it has good flow ability. The waste liquor of chemical alcohol contains a small amount of internal water, and its remains are organic matter (residual alcohol) and inorganic matter (sodium compounds). Sodium compounds are an important raw material during the production of chemical alcohol, so we should consider the recovery of sodium elements from sodium compounds in waste liquor for recycling. In addition, the organic matter in waste liquor contains considerable heat, which can generate steam for production processes or electricity generation. Therefore, it would be helpful to recycle sodium compounds and heat in the waste liquor effectively through combustion technology. This process can reduce production costs, produce economic benefits, and eliminate the discharge of pollution, making it an effective technical method.

Due to water evaporation and the release of pyrolysis volatiles in an organic state, the heating of waste liquor will cause a change of volume. The expansion of droplet volume causes a porous structure inside the particle, which increases the specific surface area and the probability of contact between the particles and oxygen. Moreover, the swelling volume index (SVI) of the droplet has a significant impact on the combustion of waste liquor [10,11]. This paper, through a comprehensive experimental study, provides a solid foundation for the combustion technology of waste liquor.

2. Experimental

2.1. Analysis of Plant Chemical Alcohol Waste Liquor

Plant chemical alcohol waste liquor is a complex multicomponent material, which is mainly composed of water, organic matter (polysaccharide compounds), and inorganic salt. Its elemental analysis and heat value data are shown in Table 2. The waste liquid element was measured by a VARIO EL cube element analyzer produced by the Elementar Company of Germany, and a waste heat generation ZDHW-YT9000 type microcomputer automatic calorimeter was used for measurement.

Table 2.

Waste liquor elemental analysis and heat value.

At room temperature, the plant chemical alcohol waste liquor was found to be brown and sticky. Its density was ρ = 1831.5 kg/m3 as measured by an electronic balance and a measuring cylinder. (We placed the empty cylinder on the electronic balance, the weight display was set to zero, the waste liquid was poured into the measuring cup, and the density was obtained by dividing the weight of the waste liquid by its volume.) This portion of the waste liquor was dissolved in nitric acid or ethanol. The “aqua regia” digestion was unable to make the solution transparent, but it could be completely dissolved in water and ethanol at the same time.

The chemical alcohol waste liquor was generally not mobile at room temperature. As the temperature increased, its flow ability increased rapidly. The relationship between the viscosity and temperature of the chemical alcohol waste liquor is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Relationship between the viscosity and temperature of the chemical alcohol waster liquor.

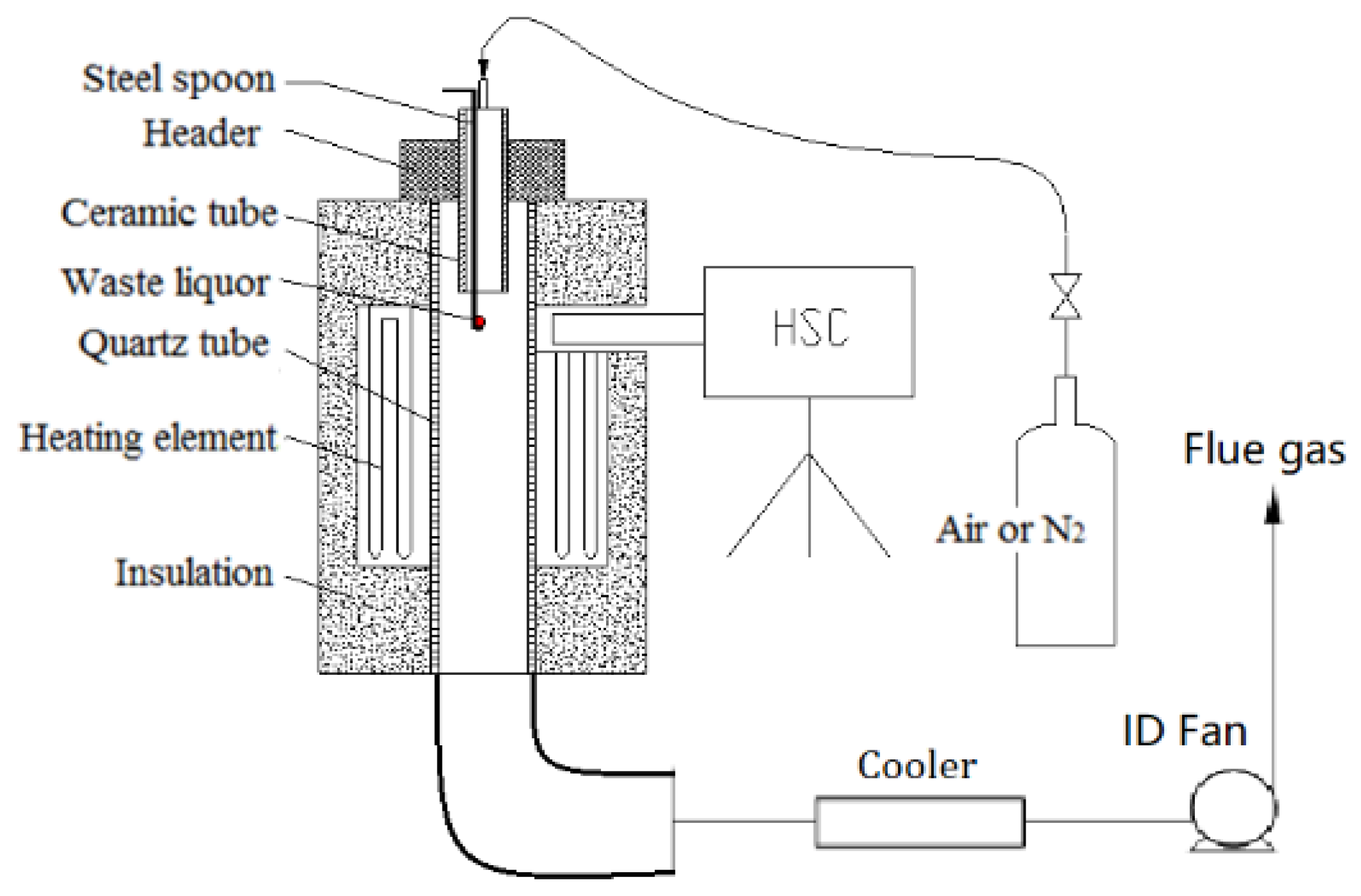

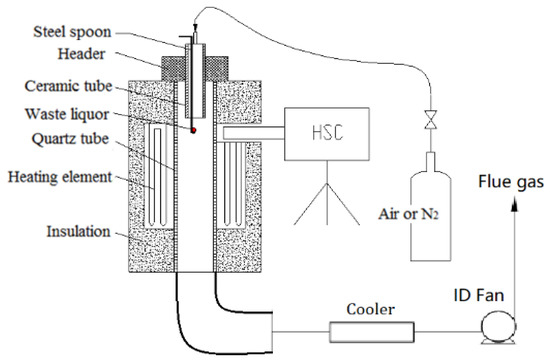

2.2. Vertical Tube Furnace

The vertical tube furnace simulated the reactive status of the droplet under a high temperature, and a high-speed camera was used to observe the swelling and ignition of the waste liquor droplet. The test platform is shown in Figure 2. The maximum temperature in the furnace, which used a silicon–molybdenum rod to heat itself, could reach 1800 °C. The observation hole on the furnace shell was reserved for a high-speed camera to film the combustion situation inside the furnace. The inner diameter of the quartz tube in the center of the test platform was 54 mm, with a length of 1045 mm; the outer diameter of the ceramic tube was 30 mm, with an inner diameter of 22 mm and a length of 400 mm.

Figure 2.

Test system diagram of vertical tube furnace.

There was a water-cooled header above the quartz tube, so the asbestos rubber gasket could not be burned out at a high temperature and could also cool the ceramic tube. An asbestos rubber gasket was used between header and quartz tube, which acted as sealing, cooling, and insulation.

A waste liquor droplet was placed on a stainless steel spoon, with the upper end extruding into the furnace through the ceramic, which was exposed to a high temperature zone in the furnace and then began to react. The upper end of the ceramic tube was plugged with a rubber plug, so the test gas would flow into the ceramic through the upper end of the ceramic. The gas flow was 8 L/min, which extruded into the upper end of the ceramic, not only guaranteeing an oxidizing or inert atmosphere around the droplets but also playing a role in cooling the ceramic tube and the sample. Relevant gas was put into the furnace for pipeline purging before the test.

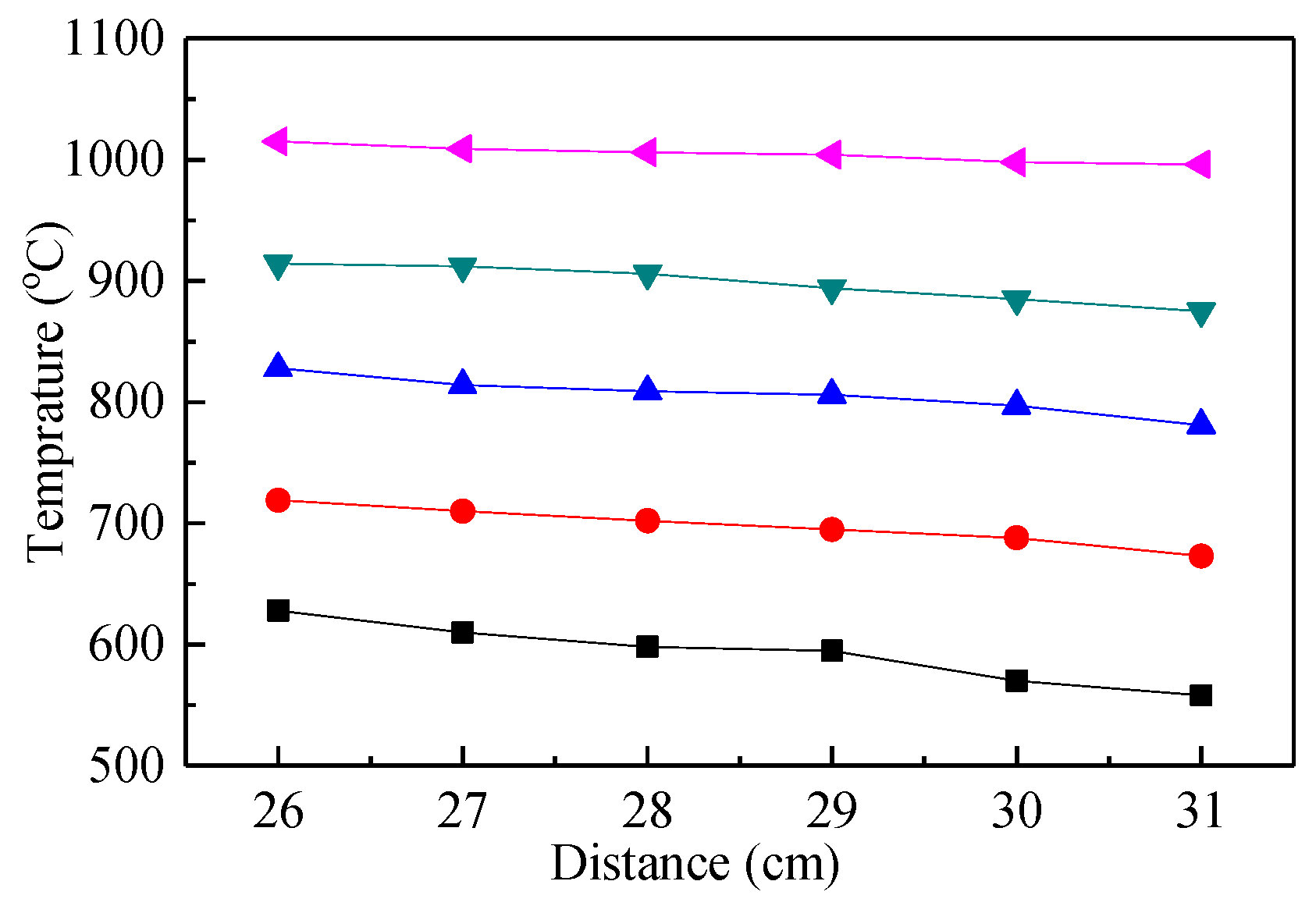

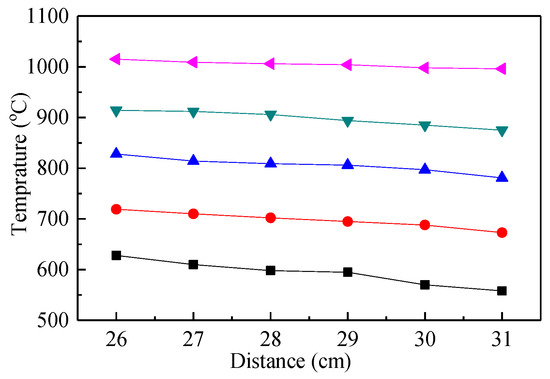

In order to ensure that the furnace reached the preset temperature, anti-high temperature insulation cotton was used to completely fill the upper and lower end of the shell and gap for insulation, except for the observation port. The position of the observation port was located 26–31 cm from the furnace roof, with a temperature point set every 1 cm. The calibration results of the temperature field at the observation port of the quartz tube are shown in Figure 3. Therefore, within the tolerance limits, the temperature of the view port could achieve the desired test temperature.

Figure 3.

Observation port temperature field diagram.

2.3. High-Speed Camera

Cooke PCO.1200s high-speed camera (HSC) is manufactured by the Cooke Corporation, USA, which is a world-famous professional high-speed camera manufacturer. This camera was used to film the reaction of the droplet in the furnace, as shown in Figure 4. The main technical parameters are shown in Table 4. The exposure time in the test was 50 ms.

Figure 4.

High-speed camera.

Table 4.

The main technical parameters of the high-speed camera.

2.4. Test Conditions

There were 30 combined test conditions using different amounts of waste liquid sample and heating temperature of the vertical tube furnace (shown in Table 5).

Table 5.

Test conditions for swelling characteristics.

2.5. Test Method

The waste liquid was heated to above 90 °C by a heater to make it a fluid. We placed the test metal spoon onto the electronic balance, returned the electronic balance to zero, and slowly dropped the waste liquid into the spoon through a heat-resistant syringe until the weight required by the experiment was reached. This test allowed the droplet quality to have an error of ±5%. At the upper head of the vertical tube furnace, there was a hole reserved for the placement of the spoon. The metal spoon for the waste liquid was quickly fed into the furnace from the seal, and a bend was used at the upper end of the metal. We ensured the depth of insertion into the furnace. After the metal spoon was sent into the furnace, the waste liquid began to expand due to heat, and the entire process was recorded using a high-speed camera. The expansion characteristics of the waste liquid were expressed by SVI. The expansion index, which refers to the ratio of the volume of droplets during the heating process to the mass of the original droplet, was used as an important parameter to characterize the expansion characteristics of the waste liquid during heating. This value can be obtained by Equation (1) as follows [12]:

where (cm3) is the volume after the droplet particles are expanded and refers to the volume at the maximum expansion under the same working condition, (mg) is the initial weight of the waste liquid droplets, and (cm3/g) is the swelling volume index.

The waste liquid expansion time was used as an important parameter to characterize the rapid expansion of the droplet. The shorter the time, the faster the expansion. This value refers to the time it takes for the droplet to travel with the metal spoon into the vertical tube furnace to the maximum volume and can be expressed by Equation (2):

where represents the expansion time, is the time at which the droplets are fed into the furnace to start heating, and is the time at which the droplets have the largest volume.

The volume of chemical alcohol waste liquid in the metal spoon was measured after heating in a vertical tube furnace. After the droplet expanded, it could be approximated as an ideal sphere. Graphical analysis of droplet expansion images were recorded by the high-speed camera. The maximum swelling volume can be obtained by Equation (3) as follows [13]:

where (cm2) refers to the projection area of the maximum swelling volume of the droplet.

3. Results and Discussion

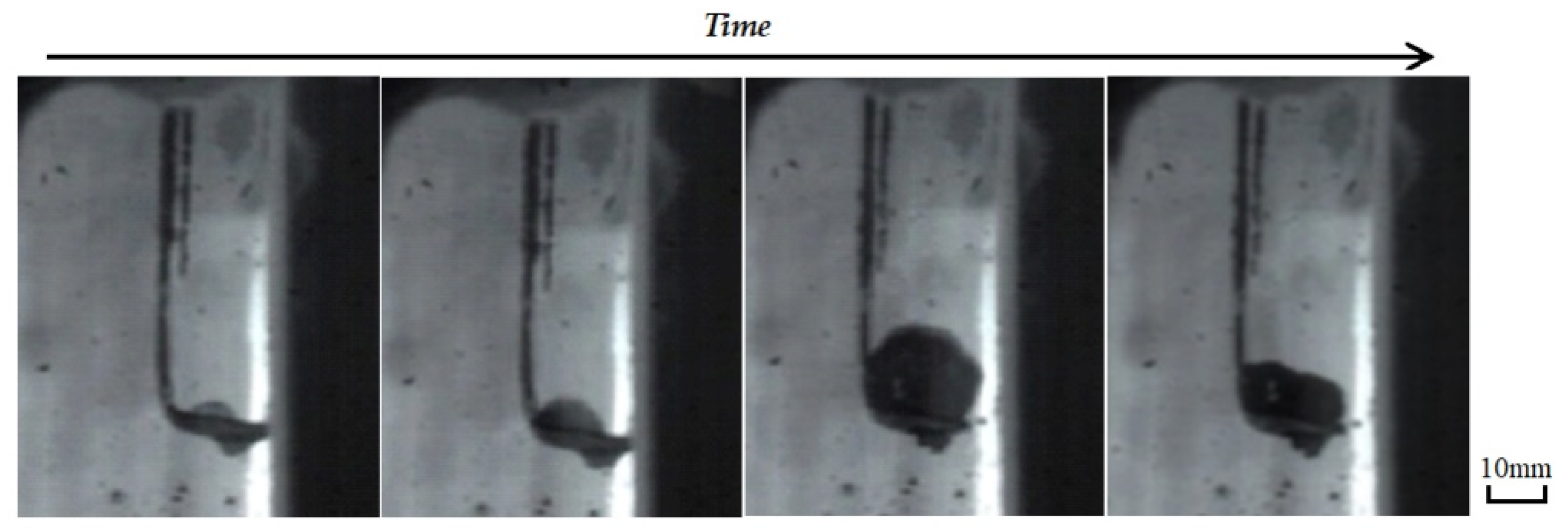

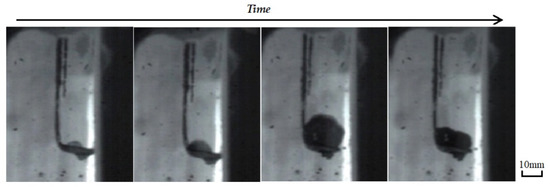

During the reaction, the waste liquids were dropped on the metal spoon and placed in a vertical tube furnace. The effects of droplet quality, heating temperature, atmosphere, and other conditions on the expansion characteristics and expansion time were investigated. The volume expansion of the waste liquid droplets after heating in the vertical tube furnace is shown in Figure 5. As the droplet length increased with an increase in the heating time, the volume first increased and then became smaller, and the maximum volume appeared in the middle.

Figure 5.

The volume expansion of the waste liquid droplets.

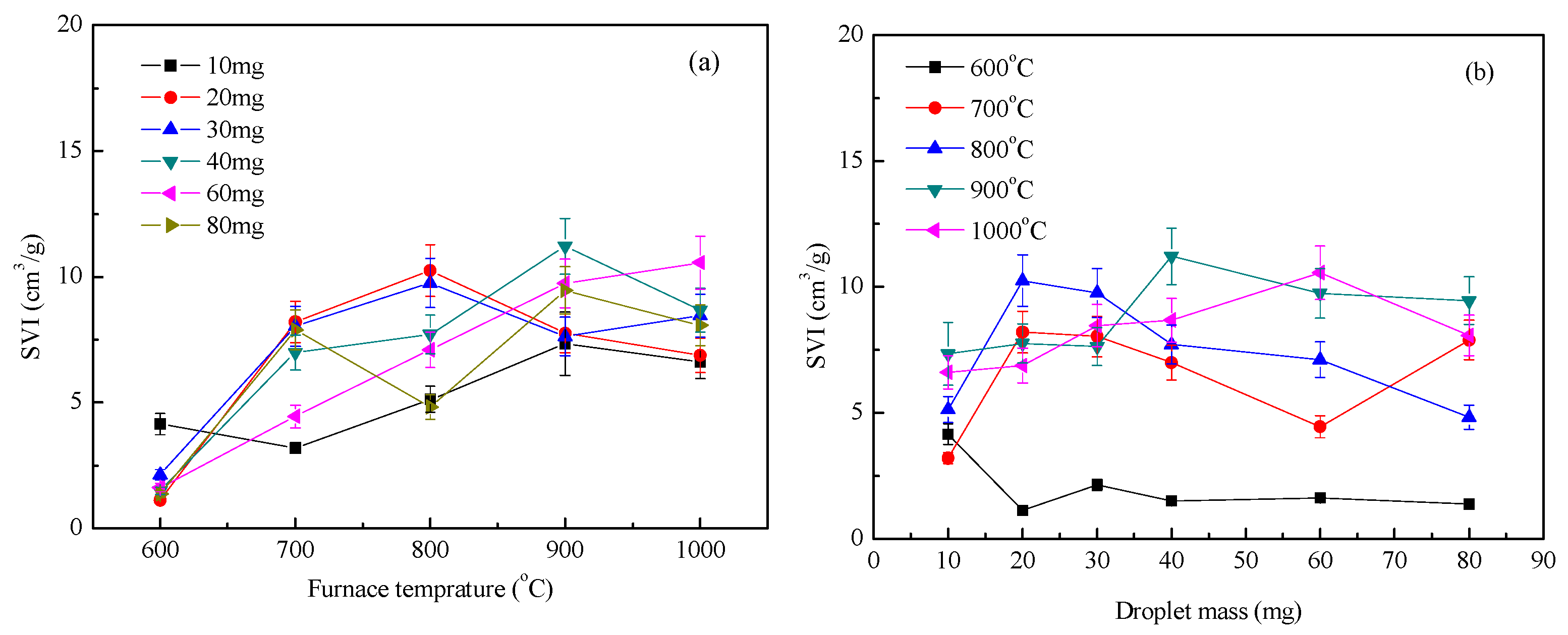

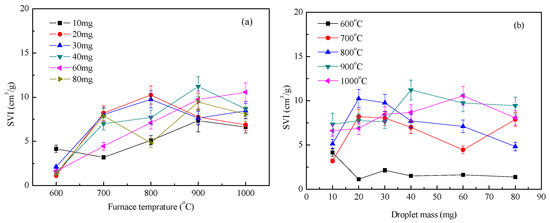

Figure 6 shows the expansion index under a nitrogen atmosphere. Figure 6a shows the effect of furnace temperature on the expansion index, and Figure 6b is the effect of droplet mass on the expansion index. Tests showed that the overall expansion index of the droplets increased with increasing temperature, while the index of droplet expansion varied little with mass. The expansion process of the droplets at high temperatures was accompanied by the evaporation of water, the precipitation of volatiles, and multiphase chemical reactions [14]. The surface temperature of the droplet rose very quickly [15]. The surface of the droplets was volatilized to analyze the volume expansion during this process to form hollow microspheres, which increased the heat and mass transfer efficiency of the surface [16]. The residual carbon on the surface of the droplet reacted with the internal moisture by self-gasification (C + H2O → CO + H2) [17]. The higher the furnace temperature, the more obvious was the reaction. This significantly changed the pore structure of the droplets, which was beneficial to the volume expansion of the droplets [18]. At 600 °C, the droplets were mainly precipitated by moisture and some volatiles. The reaction process was slow, and it remained difficult to form porous solid particles; the expansion index was also relatively small.

Figure 6.

Waste liquor swelling volume index (SVI) under nitrogen condition: (a) SVI with furnace temperature; (b) SVI with droplet mass.

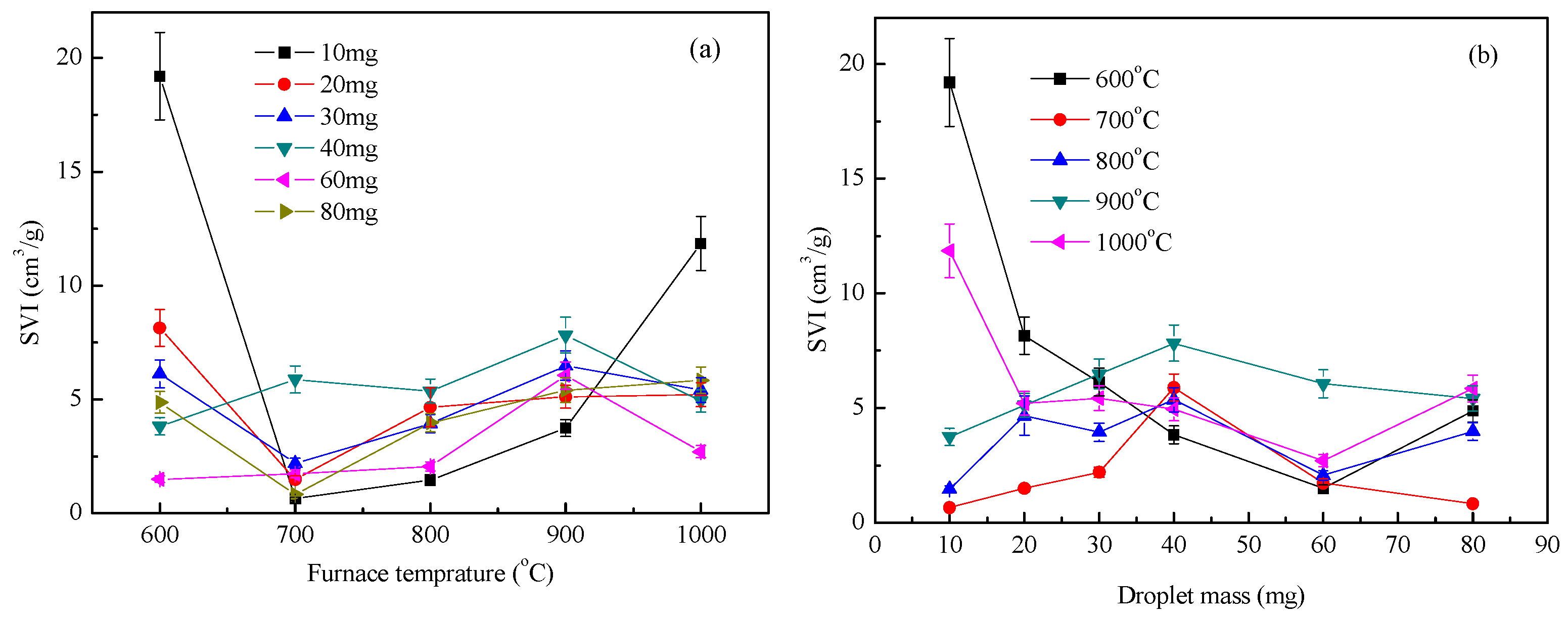

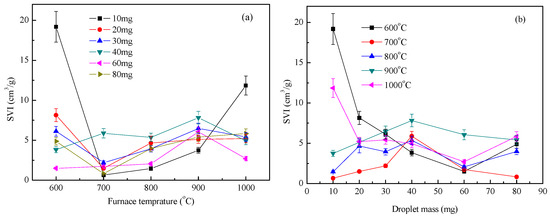

Figure 7 shows the distribution index of waste liquid expansion under an air atmosphere. The droplet expansion index decreased first and then increased with an increase in furnace temperature and decreased slightly with an increase in the droplet quality, but the amplitude was small. When the droplets were heated in an air atmosphere, the expansion characteristics of the waste liquid became complicated due to the participation of O2 in the air, especially at high temperatures. Chemical reactions, including C/CO2, C/O2, and C/Na, were also considered [19,20]. During the test, no fire was observed when the furnace temperature was 600 °C. When the temperature was above 700 °C, an obvious flare was observed, indicating that the expansion process of the waste liquid at a high temperature was accompanied by a violent combustion reaction. When the furnace temperature was less than 600 °C, the expansion process of the droplets was mainly due to the evaporation of water and pyrolysis of the waste liquid, which caused the droplet volume to increase sharply [21]. However, when the droplet size increased, the specific surface area decreased, the heat transfer and mass transfer became slower, and the oxidation of the air formed a dense shell on the surface of the droplet, which hindered the volume expansion of the droplet. When the furnace temperature was 700–1000 °C, the droplet evaporation and small molecule evaporation analysis time was very short—that is, by entering the macromolecular pyrolysis stage, a large amount of gas was released and accompanied by combustion, and the droplet expansion index reached the maximum value [22]. When the mass of the droplet increased, the precipitation inside the droplet was weaker than the combustion reaction on the surface, and the droplet expansion index became smaller. However, as the sodium salt melt began to react with the char, the expansion index of the large mass droplets increased [23].

Figure 7.

Waste liquor SVI under air condition: (a) SVI with furnace temperature; (b) SVI with droplet mass.

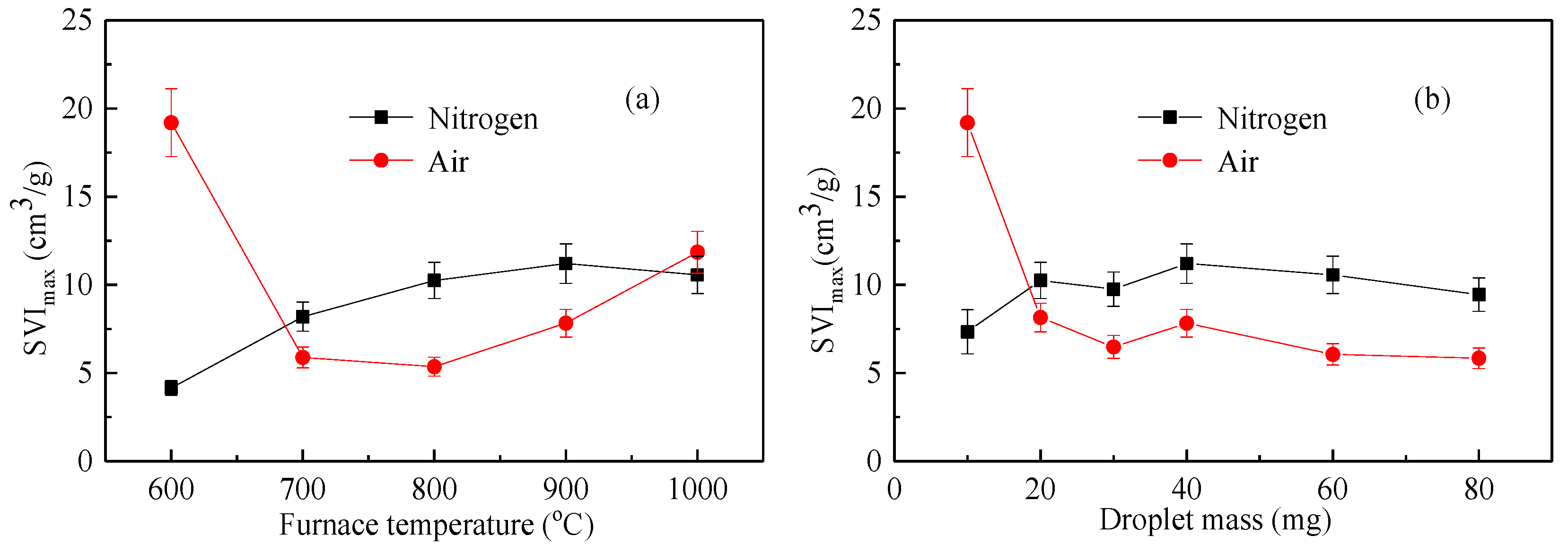

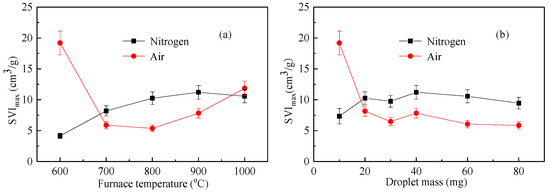

As shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8, the variation index of the expansion index of the liquid droplets under an inert atmosphere and oxidizing atmosphere was completely different. The volume expansion of the droplets under an inert atmosphere was mainly the effect of moisture evaporation and volatilization analysis. The higher the temperature, the faster the volatile analysis and the larger the SVI index. Under an oxidizing atmosphere, the expansion of droplets was related to the analysis of moisture and volatilization as well as the participation of oxygen around the droplets. The influencing factors increased, and the regularity of SVI was not affected by temperature [24].

Figure 8.

The maximum swelling volume index (SVImax) of the waste liquor in the vertical tube furnace: (a) SVImax with furnace temperature; (b) SVImax with droplet mass.

Figure 8 shows the maximum swelling volume index (SVImax) as a function of temperature and mass under nitrogen and air atmospheres. Figure 8a considers the effect of temperature on SVImax, while Figure 8b considers the effect of mass on SVImax. As can be seen from the figure, the maximum expansion index under a nitrogen atmosphere was substantially larger than that of the air atmosphere except at a lower temperature and a lower mass. This shows that, due to the presence of air, the surface of the droplet reacted with oxygen, destroying the porous structure of the droplet and reducing the maximum expansion index [25].

It can be seen from the thermal test results of the above vertical tube furnace that the plant chemical alcohol waste liquid had a high expansion index of 5 to 10 cm3/g and a volume expansion of more than 5 times. This value is between the straw black liquor and the wood pulp black liquor.

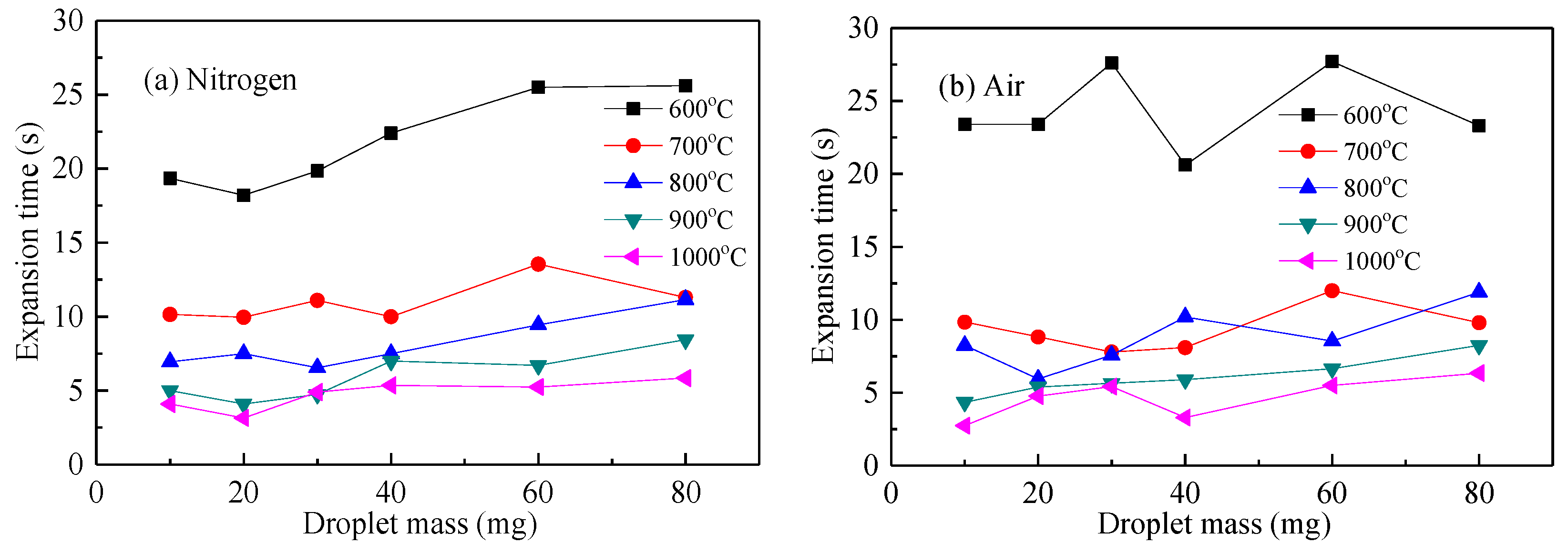

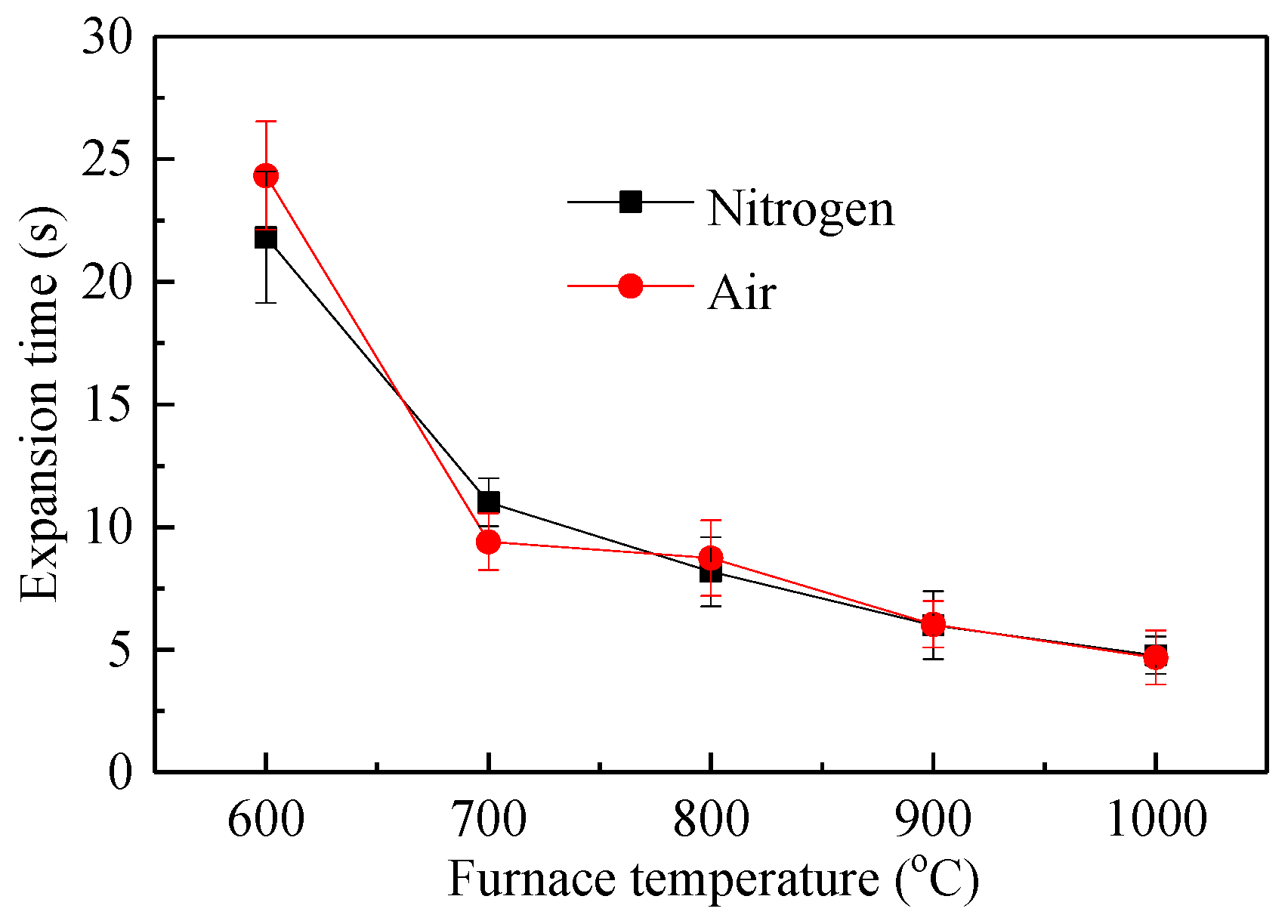

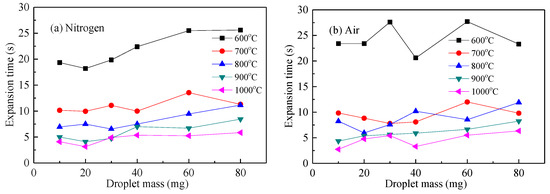

Figure 9 shows the droplet expansion time of the waste liquid droplets under nitrogen and air atmospheres. At the same temperature in Figure 9a,b, the droplet expansion time increased slightly with its mass. Under the same weight, the higher the temperature, the shorter was the expansion time. This indicated that a smaller particle size and larger temperature were beneficial to help the droplets absorb heat, speed up the analysis of moisture and volatilization, accelerate the process of droplet expansion, and shorten the expansion time. The decomposition temperature of macromolecular inorganics in chemical alcohol waste liquid was relatively high and quickly resolved after 600 °C, so the difference in expansion time between 600 and 700 °C was obviously greater than in other temperature conditions [26].

Figure 9.

Swelling time curve of waste liquor droplet. (a) expansion time with droplet mass in N2; (b) expansion time with droplet mass in air.

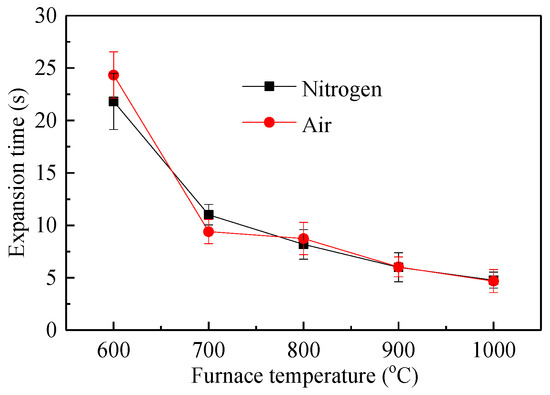

Figure 10 shows the relationship between the expansion time and the furnace temperature. The expansion time decreased rapidly with an increase in the heating temperature, and the expansion time curves of the two atmospheres were basically coincident, indicating that the influence of the atmosphere on the expansion time was small. Because the oxygen in the air participated in the surface reaction of the droplets, there was a certain difference in the expansion time at some positions.

Figure 10.

Swelling time vs. furnace temperature.

4. Conclusions

- The swelling properties of plant chemical alcohol waste liquid droplet in the vertical tube furnace under air atmosphere were more complex than those under an N2 atmosphere. Except for the 10 mg sample, the maximum SVI in N2 was bigger than that in air.

- With the same temperature in the vertical tube furnace, the swelling time slowly increased with an increase in the particle mass. At the same particle mass, the higher the temperature, the lower was the swelling time. When the temperature was higher than 700 °C, the swelling time in air was less than that in N2.

- The SVImax was >>1/ρ of plant alcohol chemical waste. A bigger SVI of the waste liquor meant that more pores were produced during the heating or combustion of the waste liquor. A suitable particle size, higher furnace temperature, and adequate residence time were beneficial to the swelling of the waste liquor, thereby playing an important role in improving the performance of waste combustion.

Author Contributions

D.W., G.Z. and Y.L. conceived and designed the experiments; D.W. and Y.L. performed the experiments; D.F., Y.Z. (Yu Zhang). and C.D. analyzed the data; D.W. and Y.Z. (Yijun Zhao) contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools; D.W. wrote the paper.

Funding

This work was funded by the China Natural Science Foundation of Innovative Research Group (51421063) and the National Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents of China (BX20180086), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation Funded Project (2018M641826), Heilongjiang Provincial Postdoctoral Science Foundation, Foundation of State Key Laboratory of High-Efficiency Utilization of Coal and Green Chemical Engineering (2018-K20), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. HIT. NSRIF. 2020052).

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the China Natural Science Foundation of Innovative Research Group (51421063) and the National Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents of China (BX20180086), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation Funded Project (2018M641826), Heilongjiang Provincial Postdoctoral Science Foundation, Foundation of State Key Laboratory of High-Efficiency Utilization of Coal and Green Chemical Engineering (2018-K20), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. HIT. NSRIF. 2020052).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Basu, P.; Basu, P. Biomass gasification and pyrolysis: Practical design and theory. Compr. Renew. Energy 2010, 25, 133–153. [Google Scholar]

- Kamm, B.; Gruber, P.R.; Kamm, M. Biorefineries–Industrial Processes and Products. In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhang, L.; Sun, S. Catalytic mechanism of ion-exchanging alkali and alkaline earth metallic species on biochar reactivity during CO2/H2O gasification. Fuel 2018, 212, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, S. Catalytic effects of ion-exchangeable K+ and Ca2+ on rice husk pyrolysis behavior and its gas–liquid–solid product properties. Energy 2018, 152, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, U.; Dwivedi, N.; Vidyarthi, S.R. Effect of Catalyst Constituents on (Ni, Mo, and Cu)/Kieselguhr-Catalyzed Sucrose Hydrogenolysis. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2005, 44, 1466–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Romain, C.; Williams, C.K. Sustainable polymers from renewable resources. Nature 2016, 540, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Aldaco, K.; Flores-Loyola, E.; Aguilar-González, C.N.; Burgos, N.; Jiménez, A. Synthesis and thermal characterization of polyurethanes obtained from cottonseed and corn oil-based polyols. J. Renew. Mater. 2016, 4, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.W.; Hu, C.W.; Tang, L.; Wang, B.H. Combustion Method of Biochemical Alcohol Boiler. CN Patent CN103486573A, 12 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Feng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Sun, S. Effect of pyrolysis temperature on char structure and chemical speciation of alkali and alkaline earth metallic species in biochar. Fuel Process. Technol. 2016, 141, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saw, W.L.; Nathan, G.J.; Ashman, P.J.; Alwahabi, Z.T.; Hupa, M. Simultaneous measurement of the surface temperature and the release of atomic sodium from a burning black liquor droplet. Combust. Flame 2010, 157, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, L.T.; Baxter, L.L.; Mackrory, A.J.; Tree, D.R. Surface temperature and time-dependent measurements of black liquor droplet combustion. AlChe J. 2010, 54, 1926–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevin, W.; Rainer, B.; Mikko, H. Influence of pressure on pyrolysis of black liquor: 1. Swelling. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 663–670. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. Combustion behavior of black liquors: Droplet swelling and influence of liquor composition. Jyväsk. Univ. Jyväsk. 2017, 206, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Maček, A. Research on combustion of black-liquor drops. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 1999, 25, 275–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, W.; Lu, H.; Ip, L.; Baxter, L.L. Black liquor particle and droplet reactions: Experimental and model results. In Proceedings of the 45th Anniversary International Recovery Boiler Conference, Lahti, Finland, 3–5 June 2009; pp. 57–100. [Google Scholar]

- Järvinen, M.; Zevenhoven, R.; Vakkilainen, E.; Forssén, M. Black liquor devolatilization and swelling—A detailed droplet model and experimental validation. Biomass Bioenergy 2003, 24, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järvinen, M.P. Numerical Modeling of the Drying, Devolatilization and Char Conversion Processes of Black Liquor Droplets; Helsinki University of Technology: Helsinki, Finland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Järvinen, M.; Zevenhoven, R.; Vakkilainen, E.; Forssen, M. Effective thermal conductivity and internal thermal radiation in burning black liquor particles. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2003, 175, 873–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrick, W. Combustion Processes in Black Liquor Recovery: Analysis and Interpretation of Combustion Rate Data and an Engineering Design Model; Institute of Paper Science and Technology, Aabo Akademi: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kulas, K.A. An Overall Model of the Combustion of a Single Droplet of Kraft Black Liquor; Georgia Institute of Technology: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kevin, W.; Mika, K.; Vesa, S.; Rainer, B.; Mikko, H. Influence of pressure on pyrolysis of black liquor: 2. Char yields and component release. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 671–679. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, P.; Clay, D.; Lonsky, W. The influence of composition on the swelling of kraft black liquor during pyrolysis. Chem. Eng. Commun. 1989, 75, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gea, G.; Murillo, M.B.; Arauzo, J. Thermal Degradation of Alkaline Black Liquor from Straw. Thermogravimetric Study. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2002, 41, 4714–4721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gea, G.; Murillo, M.; Arauzo, J.; Frederick, W. Swelling behavior of black liquor from soda pulping of wheat straw. Energy Fuels 2003, 17, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, W.; Hupa, M. The effects of temperature and gas composition on swelling of black liquor droplets during devolatilization. J. Pulp Pap. Sci. 1994, 20, J274–J280. [Google Scholar]

- Demirbaş, A. Pyrolysis and steam gasification processes of black liquor. Energy Convers. Manag. 2002, 43, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).