A Process Approach to Mainstreaming Civic Energy

Abstract

:1. Introduction: Civic Energy as a Paradigm Shift

2. Methodological Approach

- Creation of a protective space in the sense defined by Smith and Raven as “generic spaces that pre-exist deliberate mobilization by advocates of specific innovations, but who exploit the shielding opportunities they provide” [28]. The concept draws on research in the field of sustainability transitions and the necessary regime shifts and is intended to allow niche actors to nurture and improve innovations within supportive socio-technical networks prior to their market launch. Such a space allows for risk-free creative destruction hardly attainable by mere adjustments to the conventional energy model from the sidelines.

- Adoption of a design framework able to host a continuous improvement process (CIP). Since a key feature of civic energy is its adaptability to changing local framework conditions, the CE process needs to provide review and adjustment provisions. In structuring the CE process we adopt Deming’s classic Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle [29] but extend this to include a Vision element to account for diverse civic energy motivations from outside the energy process (VPDCA).

- Selection of a quality management approach suited to handle value propositions beyond purely financial considerations. Since all initiatives intent on penetrating the market as competitors to the incumbent players are confronted by numerous formal requirements including quality management demands, an early process conformity with standards development is invaluable. However, only a few performance management systems are equipped to accommodate the complex societal value propositions based on multi-criteria decision making that are typical of civic energy. The European Foundation for Quality Management EFQM [30] is one such exception [31]; we adopt the strategic EFQM link between targeted process results and process enablers without at this stage prescribing a numerical relationship between the two.

- Provision for a prioritization of community stakeholder interests. Since CE addresses the differing needs of civic stakeholders, these need to be articulated and assessed—and be subjected to ongoing review—via a facilitated stakeholder mobilization effort, that acts not just as a pre-amble but calls for integration into the CE process.

- Specification of the targeted community benefits of the energy innovation. The key distinguishing characteristics between different CE processes are the benefits they deliver to a particular community. The possible gains transcend any sectoral focus and range from but are by no means limited to stable energy pricing, independence from corporate energy interests, combatting energy poverty, financing of improved social infrastructure, increase in market value of property, improved air quality, and opportunities for citizens to contribute to community culture. In line with the EFQM-strategy these targeted results entail differentiations in both the value and supply chains inherent to the process. Also, by specifying community benefits as a product of stakeholder consultations at the outset, the need for acceptance marketing typical of corporate energy dissolves.

- Selection of appropriate enablers to the targeted benefits. This pursuit of the EFQM-based link between results and what the Business Dictionary defines as the “capabilities, forces, and resources that contribute to the success of an entity, program, or project” helps avoid the pitfalls of scattered peripheral but target-unrelated activities and contributes to making civic energy happen in the sense specified by the locally-defined and expected benefits to the community. The possible range of enablers is as unrestricted as the targeted benefits and can include the provision of missing technical, administrative, or sector expertise, the enrolment of support of key individuals, legal empowerment from a responsible authority, the mobilization of a minimum consortium membership to substantiate a business model up to and including a skilled deployment of municipal procurement instruments.

- Integration of all operational elements into the emerging VPDCA design framework. The list of operational process elements is by no means original and includes feasibility assessments, business model development, performance assessment, adoption, and transfer, each of which comprises a number of sub-processes. However, their relevance to the CE process is determined by the previous stages.

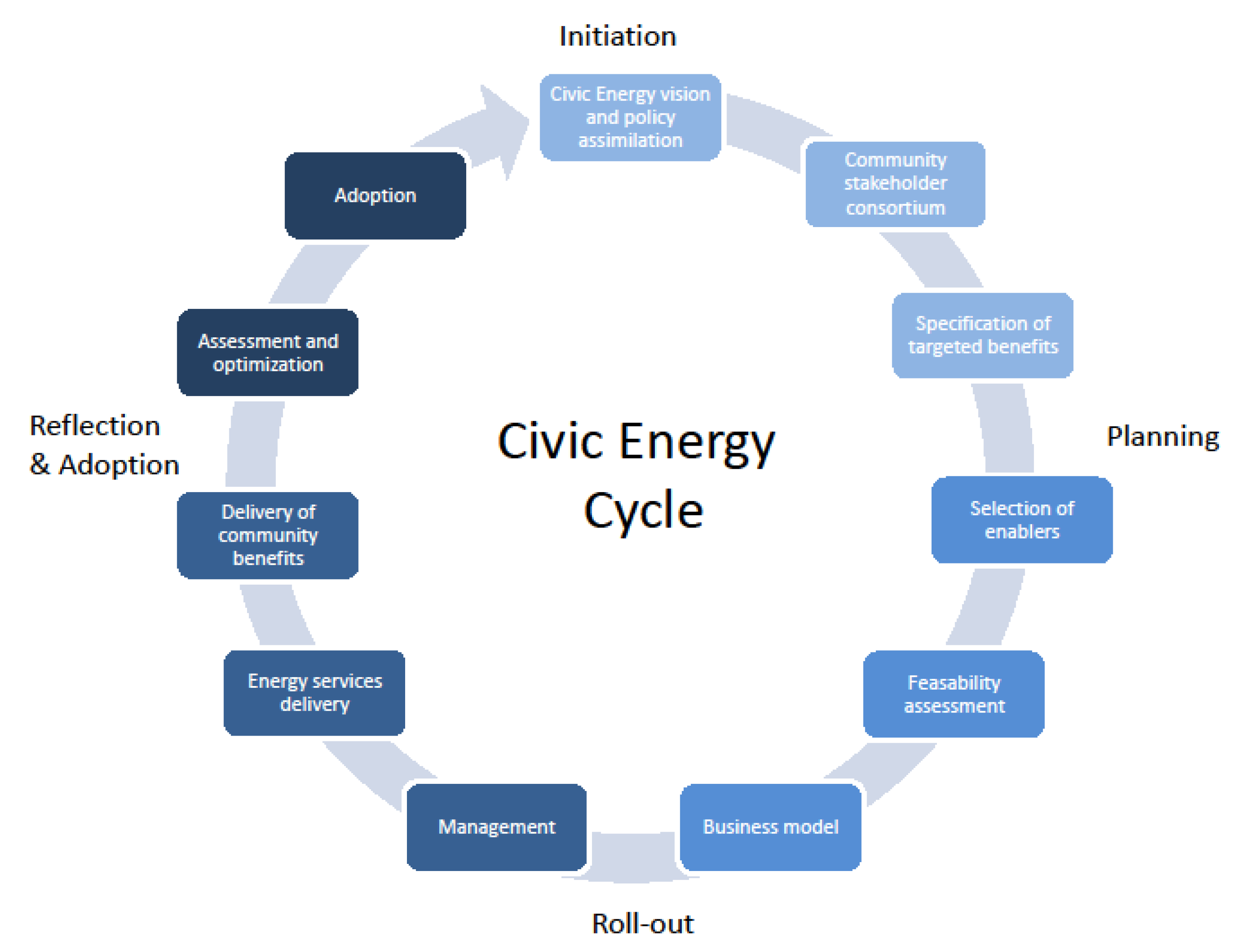

3. The Civic Energy Cycle

3.1. Civic Energy as a Continuous Improvement Process (CIP)

3.2. Process Stages and Sub-Processes

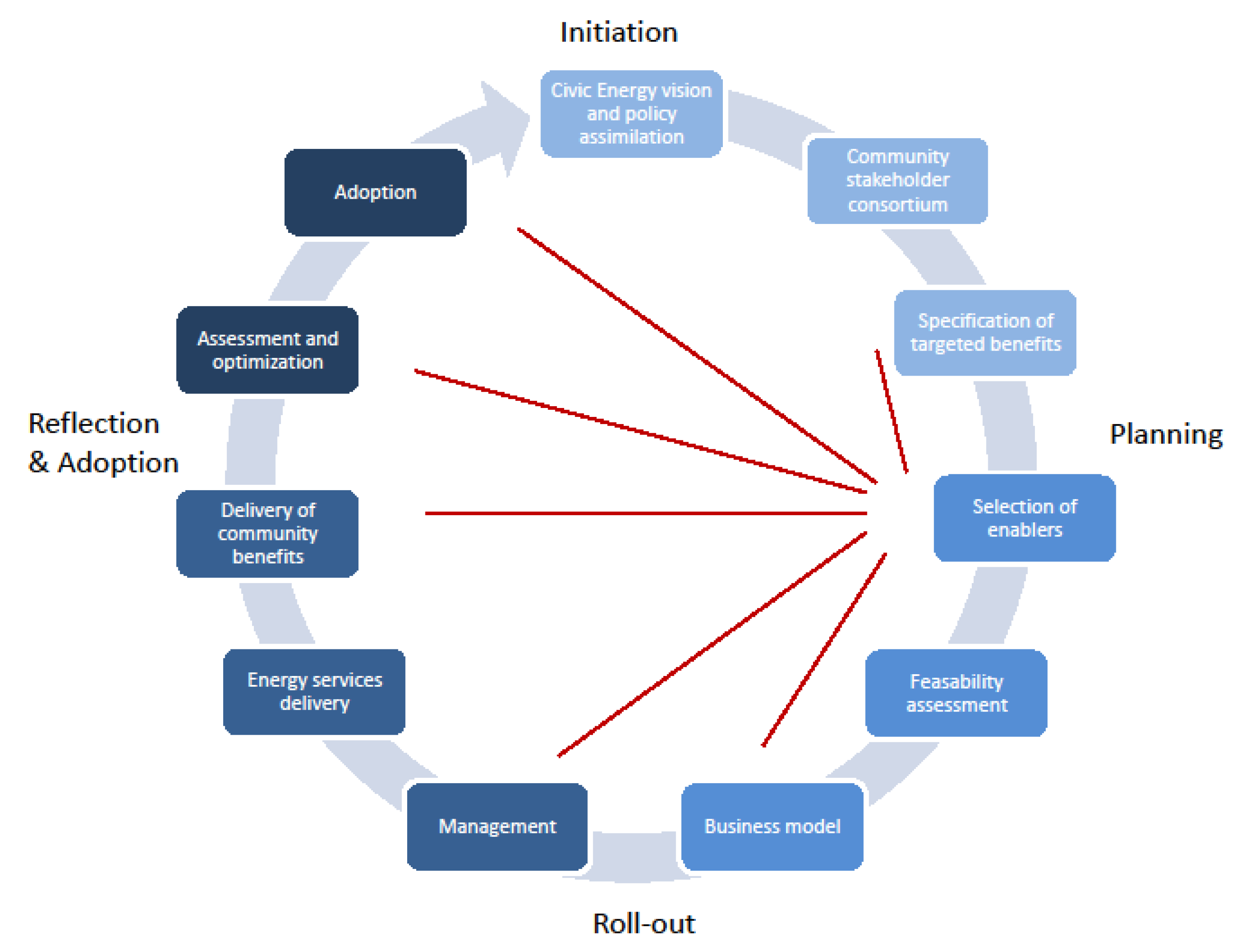

3.3. Process Interaction

- The selected benefits of the initiation phase determine the suitability and the selection of the enabling factors.

- Feasibility assessments focus not only on a review of state-of-the-art technology or market trends but specifically examine how and whether the selected enablers can deliver the hoped-for benefits, drawing on the experience of related initiatives.

- The customized business model is not based on a single currency but serves to deliver the targeted range of benefits and needs to be structured accordingly.

- Management assignments focus on the processing of the enablers.

- The roll-out of deliveries relates initially to the energy services provided but also more importantly to the civic undertaking of delivering the projected benefits to the designated recipients.

- The review activities of the fourth phase build on the structure of the feasibility assessments and include self-monitoring conducted by the stakeholders of phase one.

- Adoption decisions based on the review can entail either a re-focusing of additional community needs and benefits to be served by the installed energy system or a realignment of enablers or both.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hall, S.; Foxon, T.J.; Bolton, R. The New ‘Civic’ Energy Sector: Implications for Ownership, Governance and Financing of Low Carbon Energy Infrastructure. Available online: http://www.biee.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/Hall-The-new-civic-energy-sector.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2018).

- Seyfang, G.; Park, J.J.; Smith, A. A thousand flowers blooming? An examination of community energy in the UK. Energy Policy 2013, 61, 977–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.; Bodman, F.; Rybski, R. Community Power: Model Lega Frameworks for Citizen-Owned Renewable Energy; Client Earth: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- The Scottish Government. Scottish Energy Strategy: The Future of Energy in Scotland. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/energystrategy (accessed on 9 August 2018).

- Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning. Regional Energy Concepts in Germany. Available online: https://www.bbsr.bund.de/BBSR/EN/RP/MORO/Studies/RegionalEnergyConceptsGermany/01_start_dossier.html?nn=388868 (accessed on 9 August 2018).

- de Santoli, L.; Mancini, F.; Nastasi, B.; Piergrossi, V. Building integrated bioenergy production (BIBP): Economic sustainability analysis of Bari airport CHP (combined heat and power) upgrade fueled with bioenergy from short chain. Renew. Energy 2015, 81, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauwens, T. Explaining the diversity of motivations behind community renewable energy. Energy Policy 2016, 93, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Radtke, J. A closer look inside collaborative action: Civic engagement and participation in community energy initiatives. People Place Policy 2014, 8, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Süsser, D. People—Powered Local Energy Transition: Mitigating Climate Change with Community—Based Renewable Energy in North Frisia. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Seyfang, G.; Haxeltine, A. Growing Grassroots Innovations: Exploring the Role of Community-Based Initiatives in Governing Sustainable Energy Transitions. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2012, 30, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weinrub, A.; Giancatarino, A. Toward a Climate Justice Energy Platform: Democratizing Our Energy Future. Available online: https://community-wealth.org/content/toward-climate-justice-energy-platform-democratizing-our-energy-future (accessed on 31 July 2018).

- Angel, J. Towards Energy Democracy: Discussions and Outcomes from an International Workshop. Available online: https://www.tni.org/en/publication/towards-energy-democracy (accessed on 31 July 2018).

- European Economic and Social Committee. Changing the Future of Energy: Civic Society as a Main Player in Renewable Energy. Available online: https://www.eesc.europa.eu/resources/docs/panel-4-lribbe.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2018).

- Burke, M.J.; Stephens, J.C. Political power and renewable energy futures: A critical review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 35, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteman, M.; Wiering, M.; Helderman, J.-K. The Institutional Space of Community Initiatives for Renewable Energy: A Comparative Case Study of The Netherlands, Germany and Denmark. Available online: https://energsustainsoc.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/2192-0567-4-11 (accessed on 14 August 2018).

- Ayres, R.U.; Ayres, E. Crossing the Energy Divide. Moving from Fossil Fuel Dependence to a Clean-Energy Future; Wharton School Publishing: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W.; Tyfield, D.; Urry, J. Regime Resistance against Low-Carbon Transitions: Introducing Politics and Power into the Multi-Level Perspective. Theory Cult. Soc. 2014, 31, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- REN 21. Renewables Global Status Report 2016. Available online: http://www.ren21.net/status-of-renewables/global-status-report/ (accessed on 8 August 2018).

- Wagner, O. The wave of remunicipalisation of energy networks and supply in Germany. In Proceedings of the First Fuel Now: ECEEE 2015 Summer Study, Toulon, France, 1–6 June 2015; pp. 559–569. [Google Scholar]

- Lovins, A.B. Energy Strategy: The Road Not Taken? For. Aff. 1976, 55, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prospex Research. Europe’s Top Twenty Power Industry Players 2016. 2016. Available online: https://www.prospex.co.uk (accessed on 20 August 2018).

- Rifkin, J. The Third Industrial Revolution. How Lateral Power Is Transforming Energy, the Economy, and the World, 1st ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, J.A. The renewable energies technology surge: A new techno-economic paradigm in the making? Futures 2013, 46, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy; Routeledge: London, UK, 1976; pp. 82–83. ISBN 0415107628. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, C.M. On inclusion and network governance: The democratic disconnect of Dutch energy transitions. Public Adm. 2008, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldthau, A. Rethinking the governance of energy infrastructure: Scale, decentralization and polycentrism. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2014, 1, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.; Kunze, C. Transcending community energy: Collective and politically motivated projects in renewable energy (CPE) across Europe. People Place Policy 2014, 8, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Raven, R. What is protective space? Reconsidering niches in transitions to sustainability. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 1025–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deming, W.E. New Economics for Industry, Government, New Economics for Industry, Government, Education, New Economics for for Industry, Government, Education, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 92–116. [Google Scholar]

- European Foundation of Quality Management. EFQM Excellence Model. Available online: http://www.efqm.org/ (accessed on 24 July 2018).

- Tarí, J.J.; Molina-Azorín, J.F. Integration of Quality Management and Environmental Management Systems. Available online: https://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/abs/10.1108/17542731011085348 (accessed on 14 August 2018).

- Kivimaa, P.; Kern, F. Creative destruction or mere niche support? Innovation policy mixes for sustainability transitions. Res. Policy 2016, 45, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egyedi, T.; Spirco, J. Standards in transitions: Catalyzing infrastructure change. Futures 2011, 43, 947–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blind, K. The Impact of Standardization and Standards on Innovation. Manchester Institute of Innovation Reseach, 2013. Available online: http://research.mbs.ac.uk/innovation/ (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- Blind, K.; Petersen, S.S.; Riillo, C.A.F. The impact of standards and regulation on innovation in uncertain markets. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Standards Organisation. Standardization and Innovation, ISO-CERN Conference Proceedings, 13–14 November 2014; ISO Central Secretariat: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 1–8, 92–138. ISBN 978-92-67-10644-1. [Google Scholar]

- Münstermann, B.; Eckhardt, A.; Weitzel, T. The performance impact of business process standardization. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2010, 16, 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldthau, A. From the State to the Market and Back: Policy Implications of Changing Energy Paradigms. Glob. Policy 2012, 3, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Schoor, T.; van Lente, H.; Scholtens, B.; Peine, A. Challenging obduracy: How local communities transform the energy system. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, H.; Woodhill, J.; Hemmati, M.; Verhoosel, K.; van Vugt, S. The MSP Guide, How to Design and Facilitate Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships; Wageningen University and Research, CDI, Wageningen and Practical Action Publishing: Rugby, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-78044-965-4. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Recast Electricity Directive COM(2016) 864 Final/2. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/documents/1_en_act_part1_v7_864.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- International Energy Agency IEA. Renewable Energy Policy Recommendations. 9 October 2018. Recommendation 7. Available online: https://webstore.iea.org/20-renewable-energy-policy-recommendations (accessed on 9 October 2018).

| VPDCA Phase | Process Stage | Sub-Processes |

|---|---|---|

| Initiation (V) | Civic Energy vision and policy assimilation |

|

| Community stakeholder consortium |

| |

| Specification of targeted benefits |

| |

| Planning (P) | Selection of enablers |

|

| Feasibility assessment |

| |

| Business model |

| |

| Roll-Out (D) | Management |

|

| Energy services delivery |

| |

| Delivery of community benefits |

| |

| Reflection and Adoption (C, A) | Assessment and optimization |

|

| Adoption |

|

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McGovern, G.; Klenke, T. A Process Approach to Mainstreaming Civic Energy. Energies 2018, 11, 2914. https://doi.org/10.3390/en11112914

McGovern G, Klenke T. A Process Approach to Mainstreaming Civic Energy. Energies. 2018; 11(11):2914. https://doi.org/10.3390/en11112914

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcGovern, Gerard, and Thomas Klenke. 2018. "A Process Approach to Mainstreaming Civic Energy" Energies 11, no. 11: 2914. https://doi.org/10.3390/en11112914

APA StyleMcGovern, G., & Klenke, T. (2018). A Process Approach to Mainstreaming Civic Energy. Energies, 11(11), 2914. https://doi.org/10.3390/en11112914