A Preliminary Assessment of Health and Safety in the Automobile Industry in Brunei Darussalam: Workers’ Knowledge and Practice of Organic Solvents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design, Setting, and Sampling

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

2.2.1. Questionnaire

2.2.2. Observations (Pictorial Evidence)

3. Results

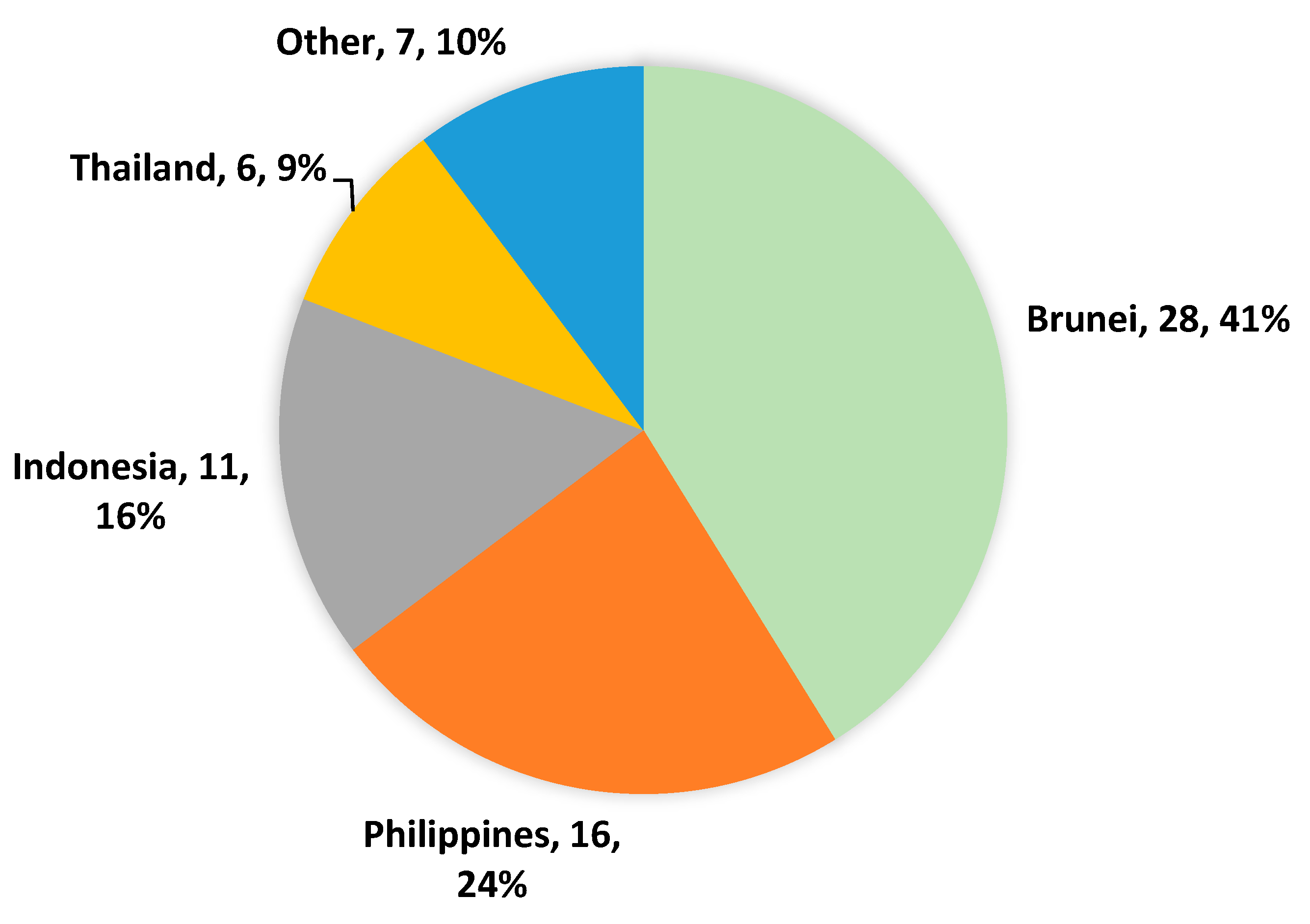

3.1. Quantitative Analysis

3.2. Qualitative Analysis

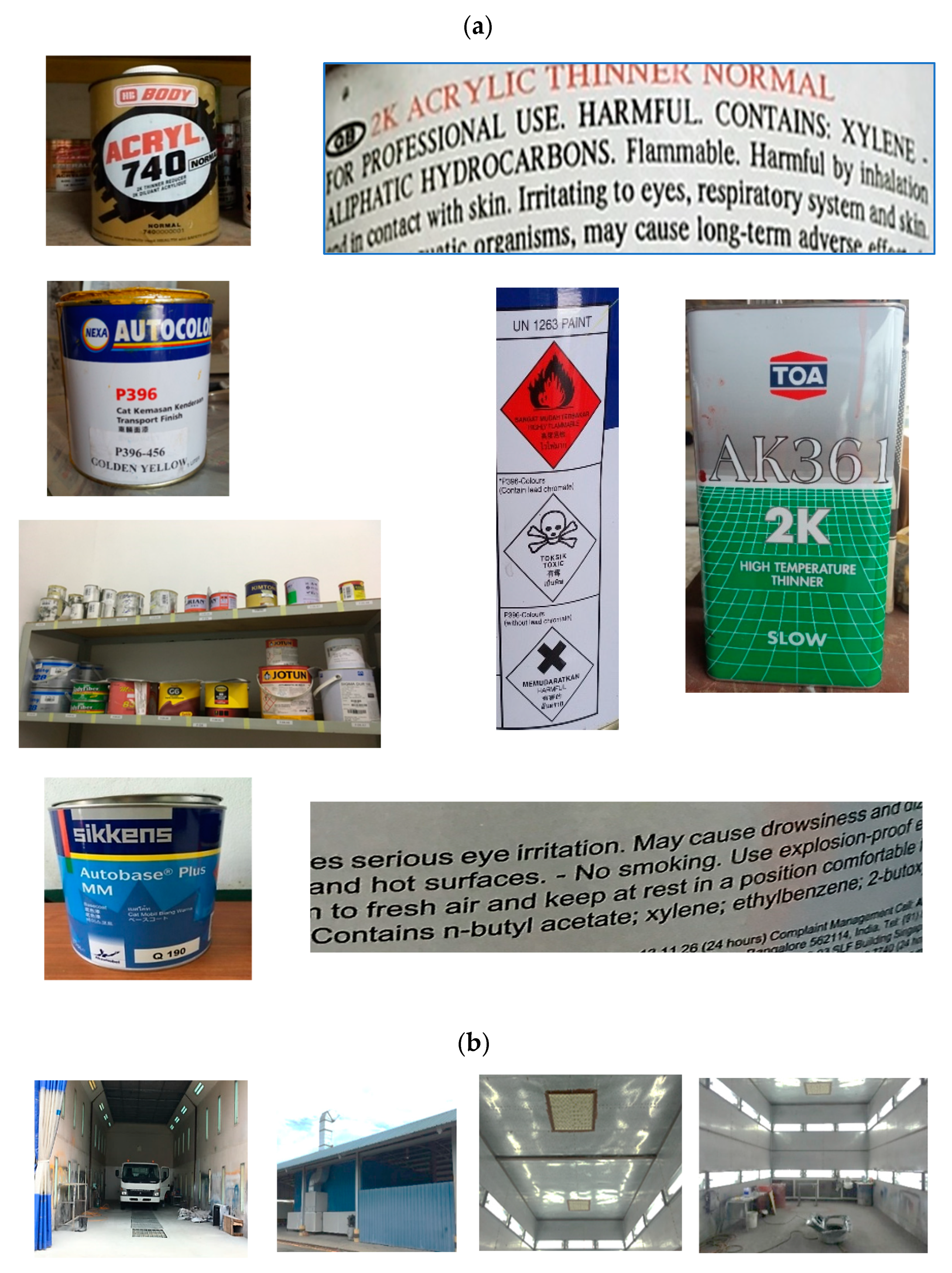

3.2.1. Theme 1: Materials Containing Organic Solvents

3.2.2. Theme 2: Knowledge of the Harmful Effects of Organic Solvents

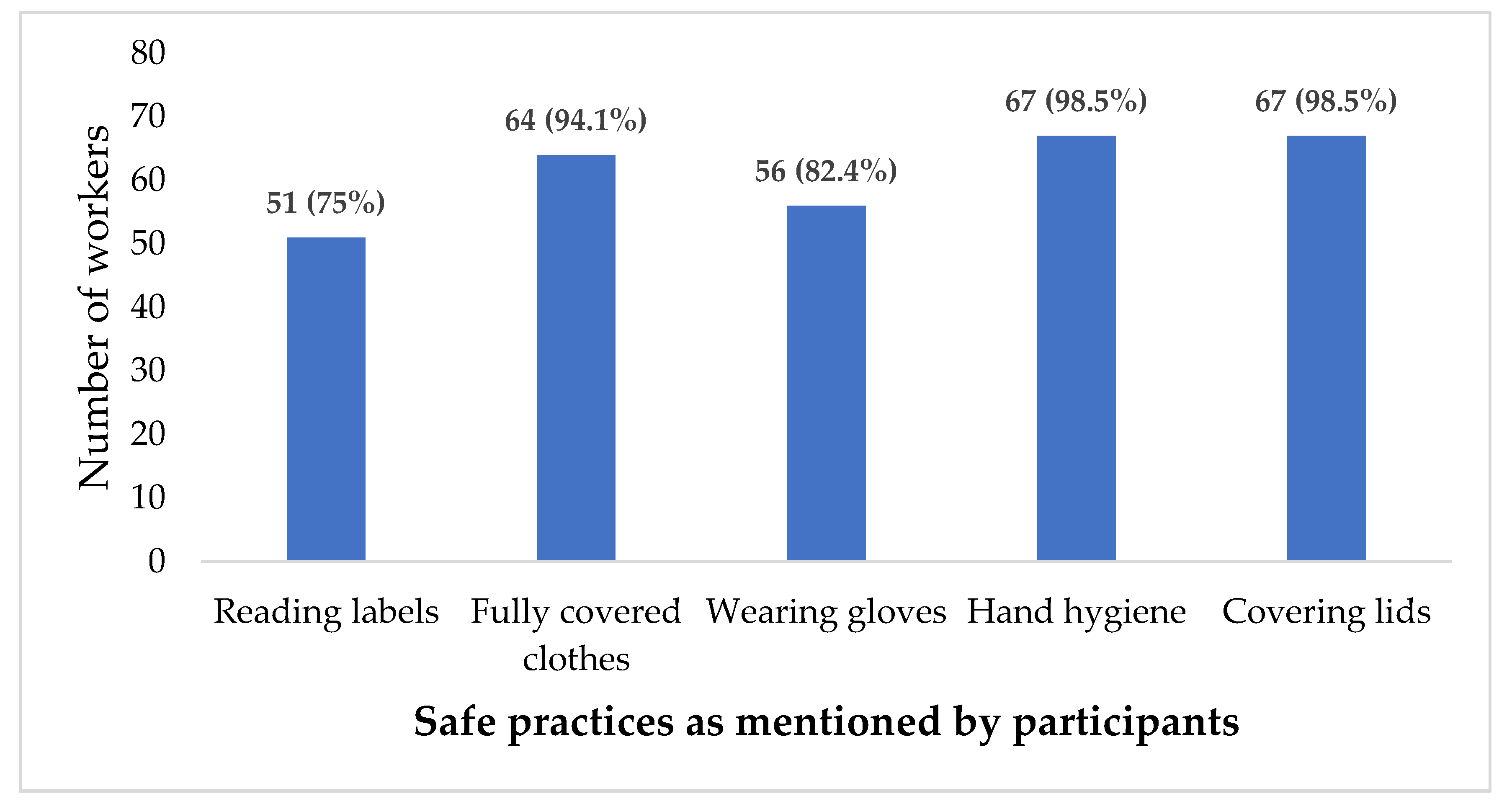

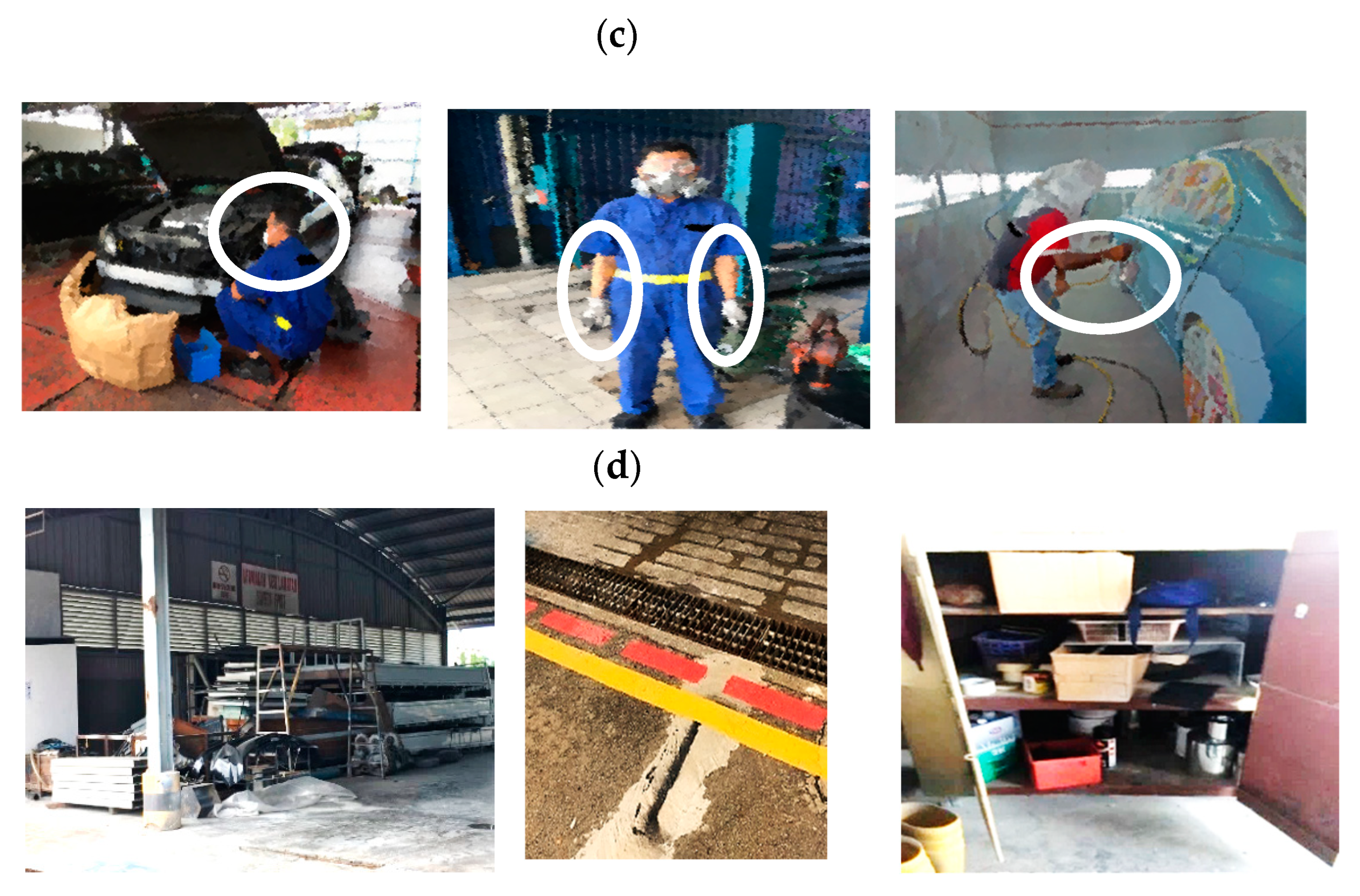

3.2.3. Theme 3: Safety Practice and Precautions

3.3. Pictorial Evidence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rutchik, J.S.; Ramachandran, T.S. Organic Solvent Neurotoxicity. Available online: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1174981-overview (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- Dick, F.D. Solvent Neurotoxicity. Occup. Environ. Med. 2006, 63, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitali, M.; Ensabella, F.; Stella, D.; Guidotti, M. Exposure to Organic Solvents among Handicraft Car Painters: A Pilot Study in Italy. Ind. Health 2006, 44, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adei, E.; Adei, D.; Osei-Bonsu, S. Assessment of Perception and Knowledge of Occupational Chemical Hazards, in the Kumasi Metropolitan Spray Painting Industry, Ghana. J. Sci. Technol. 2011, 31, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kamal, A.; Malik, R.N. Hematological Evidence of Occupational Exposure to Chemicals and Other Factors among Auto-Repair Workers in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Osong Public Health Res. Perspect. 2012, 3, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salihoglu, G.; Salihoglu, N.K. A Review on Paint Sludge from Automotive Industries: Generation, Characteristics and Management. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 169, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. N-Hexane—Related Peripheral Neuropathy Among Automotive Technicians—California, 1999–2000. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5045a3.htm (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- The Business Research Company. The Hexane Global Market Report—2022. Available online: https://www.thebusinessresearchcompany.com/report/hexane-global-market-report (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Bates, M.N.; Pope, K.; So, Y.T.; Liu, S.; Eisen, E.A.; Hammond, S.K. Hexane Exposure and Persistent Peripheral Neuropathy in Automotive Technicians. Neurotoxicology 2019, 75, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Alfaro, M.; Cárabez-Trejo, A.; Alcaraz-Contreras, Y.; Leo-Amador, G. Oxidative Stress Effects of Thinner Inhalation. Indian J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2011, 15, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, M.V.; Mesadri, J.; Gonçalves, D.F.; Cordeiro, L.M.; Franzen da Silva, A.; Obetine Baptista, F.B.; Wagner, R.; Dalla Corte, C.L.; Soares, F.A.A.; Ávila, D.S. Neurotoxicity Induced by Toluene: In Silico and in Vivo Evidences of Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Dopaminergic Neurodegeneration. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 298, 118856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, M.P.; Hammond, S.K.; Nicas, M.; Hubbard, A.E. Worker Exposure to Volatile Organic Compounds in the Vehicle Repair Industry. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2007, 4, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noraberg, J.; Arlien-Søborg, P. Neurotoxic interactions of industrially used ketones. Neurotoxicology 2000, 21, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Land Transport Department. Road Accident Statistics 2014–2016. Available online: https://www.jpd.gov.bn/SitePages/Land%20Transport%20Department/Statistics/Road%20Accident%20Statistics%202014-2016.aspx (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- Safety Health and Environment National Authority (SHENA). Workplace Safety and Health Order 2009. Available online: http://www.shena.gov.bn/SitePages/Workplace%20Safety%20and%20Health%20Order%202009.aspx (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- Yu, I.T.; Lee, N.L.; Wong, T.W. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Regarding Organic Solvents among Printing Workers in Hong Kong. J. Occup. Health 2005, 47, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED—2011). Available online: http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/international-standard-classification-of-education-isced-2011-en.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- Afolabi, F.J.; de Beer, P.; Haafkens, J.A. Can Occupational Safety and Health Problems Be Prevented or Not? Exploring the Perception of Informal Automobile Artisans in Nigeria. Saf. Sci. 2021, 135, 105097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, W.; Poth, N. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Workplace Gender Equality Agency Annual Report 2019–2020. Available online: https://www.transparency.gov.au/annual-reports/workplace-gender-equality-agency/reporting-year/2019-20 (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- Yamauchi, M. Employment Practices in Japan’s Automobile Industry: The Implication for Divergence of Employment Systems under Globalization. Evol. Inst. Econ. Rev. 2021, 18, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs, Automotive Industry. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/automotive-industry_en (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- Norredam, M.; Agyemang, C. Tackling the Health Challenges of International Migrant Workers. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e813–e814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. An ILO Code of Practice—Safety in Use of Chemicals at Work. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_protect/@protrav/@safework/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_107823.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- Heitbrink, W.A.; Wallace, M.E.; Bryant, C.J.; Ruch, W.E. Control of Paint Overspray in Autobody Repair Shops. Am. Ind. Hyg. Assoc. J. 1995, 56, 1023–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aqtam, I.; Darawwad, M. Health Promotion Model: An Integrative Literature Review. Open J. Nurs. 2018, 08, 485–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Age Groups (years) | |

| <30 | 8 (11.8%) |

| 30–40 | 21 (30.8%) |

| 41–50 | 24 (35.3%) |

| ≥50 | 15(22.1%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 67 (98.5%) |

| Female | 1 (1.5%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Malay | 9 (13.2%) |

| Chinese | 19 (27.9%) |

| Others | 40 (58.8%) |

| Education | |

| Primary | 38 (55.9%) |

| Secondary | 24 (35.3%) |

| Tertiary | 6 (8.8%) |

| Smoking | |

| Current Smoker | 27 (39.7%) |

| Ex-Smoker | 09 (13.2%) |

| Non-Smoker | 32 (47.1%) |

| Alcohol | |

| Consumes alcohol | 27 (39.7%) |

| Past alcohol consumption | 09 (13.2%) |

| No alcohol | 32 (47.1%) |

| Work Activity | |

| Painter | 24 (35.3%) |

| Body repair | 12 (17.6%) |

| Mechanic | 14 (20.6%) |

| Panel beater | 5 (7.4%) |

| Others | 13 (19.1%) |

| Frequency (%) | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Total | |||

| Ethnicity | Malay | 9 (14.3%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (13.2%) | 0.243 b |

| Chinese | 19 (30.2%) | 0 (0%) | 19 (30.2%) | ||

| Others | 35 (55.6%) | 5 (100%) | 40 (58.8%) | ||

| Age group | 20–24 | 3 (4.8%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (4.4%) | 0.742 b |

| 25–29 | 5 (7.9%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (7.4%) | ||

| 30–34 | 11 (17.5%) | 1 (20%) | 13 (19.1%) | ||

| 35–39 | 7 (11.1%) | 1 (20%) | 8 (11.8%) | ||

| 40–44 | 9 (14.3%) | 1 (20%) | 10 (14.7%) | ||

| 45–49 | 13 (20.6%) | 1 (20%) | 14 (20.6%) | ||

| ≥50 | 15 (23.8%) | 0 (0%) | 15 (22.1%) | ||

| Education level | Low education | 37 (58.7%) | 1 (20%) | 38 (55.9%) | 0.107 b |

| Medium education | 20 (31.7%) | 4 (80%) | 24 (35.3%) | ||

| High education | 6 (9.5%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (8.8%) | ||

| Factors | Questionnaire | Participants | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | ||

| Knowledge of organic solvents | “Most of the organic solvents which we are using now are the ingredients in the Lacquer thinner that we mix with the spray paints.” | 52 | 76.47 |

| “I use thinner to mix with car paints that contain organic solvents; it is for clear, hardener and appears to get more glossy car paints.” | 5 | 7.35 | |

| “The organic solvents are in the materials that I deal with, such as thinner, degreaser, colour paint materials, and other volatile organic compounds such as engine oil and greases.” | 56 | 82.35 | |

| “My work is repairing engines. Some solvents that I have used during work include; greases, synthetic oil, engine oil, brake fluids and gearbox oil. I also use benzene to clean engine parts to make them shine.” | 2 | 2.94 | |

| Knowledge of harmful effects of organic solvents | “It causes skin irritation if spilled or if in contact with organic solvents. Lungs defects can happen if we inhale.” | 53 | 77.94 |

| “Organic solvents can damage the kidneys, lungs and skin. Skin can be very itchy and dry if in contact. Small particles from solvents may be inhaled that can either damage the lungs or cause lung cancer if there is long-term exposure.” | 9 | 13.23 | |

| “The solvents may possibly be inhaled through the nose going to the lungs. Hand chemicals such as thinner also can affect the skin causing skin disease. The long-term use of organic solvents may affect the liver.” | 55 | 80.88 | |

| “Organic solvents cause skin irritation through direct contact, leading to lung problems due to inhalation”. | 5 | 7.35 | |

| “Organic Solvents can cause hallucinations if exposed to over the long-term and suffocation if inhaled in the case of working without proper respiratory protection.” | 21 | 30.88 | |

| Safety Practices and Precautions | “Safety is the first thing before starting painting work. It is better to know the safety procedures; like wearing PPE such as safety goggles, boots, gloves and mask (half-face for preparation stage and full-face during painting).” | 2 | 2.94 |

| “We use disposable masks for daily car repairs so that we will prevent ourselves from inhaling dangerous chemicals like solvents used in car repairs. We also use a full-face respirator (half-face with gas canister) to minimize the paint exposure. We check the gas canister 3 times a week.” | 50 | 73.52 | |

| “Every time we work in the automotive industry and use chemical materials, we need to follow the instructions for each item.” | 40 | 58.82 | |

| “The Local Exhaust Ventilation (LEV) must be switched on during spray painting to prevent inhalation of dust from spray paints. We also need to wear rubber gloves, a respirator and safety shoes whilst painting.” | 6 | 8.82 | |

| “Make sure that surrounding places are clear and working must not be in open places. The painting room must be well ventilated with equal air in and air out. Wear safety goggles and a mask. All doors must be locked and the LEV switched on. Prepare air breathing systems and painting booth ventilation equipment, organize the requisition of paint and solvents.” | 39 | 57.35 | |

| “The ‘No Entry’ sign must be switched on while performing spray painting or heating cars using an oven. This is to prevent other people coming in during the procedure and to prevent inhaling dust from the spray paint that contains harmful organic solvents.” | 11 | 16.17 | |

| “Prepare sand to clear up any oil spills. Used oil to be absorbed with chemicals. Paint sticking on paint brushes are cleaned up using lacquer.” | 39 | 57.35 | |

| “Wash hands with soap because if we use thinner, then it can cause irritation to the skin. Used oil after car repairs must be properly disposed of.” | 57 | 83.82 | |

| “PPE is cleaned. Dispose of one time used items. Clean the workshop area. Wash hands after finish working. Tidy things up, and keep all tools and chemicals in a cabinet. For the painting room; it needs to be cleaned and unwanted chemicals also need to be cleared and disposed of. We segregate the chemicals, plastic, paper and used oil properly and they are disposed of properly.” | 35 | 51.47 | |

| “We use special soap provided by the company to wash our hands. Occasionally, we also use thinner to clean off paints and grease from the hands.” | 48 | 70.58 | |

| “If it is difficult to perform my work, I will remove my gloves.” | 2 | 2.94 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hasylin, H.; Abdul-Mumin, K.H.; Pg-Hj-Ismail, P.-K.; Trivedi, A.; Win, K.N. A Preliminary Assessment of Health and Safety in the Automobile Industry in Brunei Darussalam: Workers’ Knowledge and Practice of Organic Solvents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15469. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315469

Hasylin H, Abdul-Mumin KH, Pg-Hj-Ismail P-K, Trivedi A, Win KN. A Preliminary Assessment of Health and Safety in the Automobile Industry in Brunei Darussalam: Workers’ Knowledge and Practice of Organic Solvents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15469. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315469

Chicago/Turabian StyleHasylin, Hazimah, Khadizah H. Abdul-Mumin, Pg-Khalifah Pg-Hj-Ismail, Ashish Trivedi, and Kyaw Naing Win. 2022. "A Preliminary Assessment of Health and Safety in the Automobile Industry in Brunei Darussalam: Workers’ Knowledge and Practice of Organic Solvents" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15469. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315469

APA StyleHasylin, H., Abdul-Mumin, K. H., Pg-Hj-Ismail, P.-K., Trivedi, A., & Win, K. N. (2022). A Preliminary Assessment of Health and Safety in the Automobile Industry in Brunei Darussalam: Workers’ Knowledge and Practice of Organic Solvents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15469. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315469