Partially Thrombosed Internal Maxillary Pseudoaneurysm After Gunshot Wound

Abstract

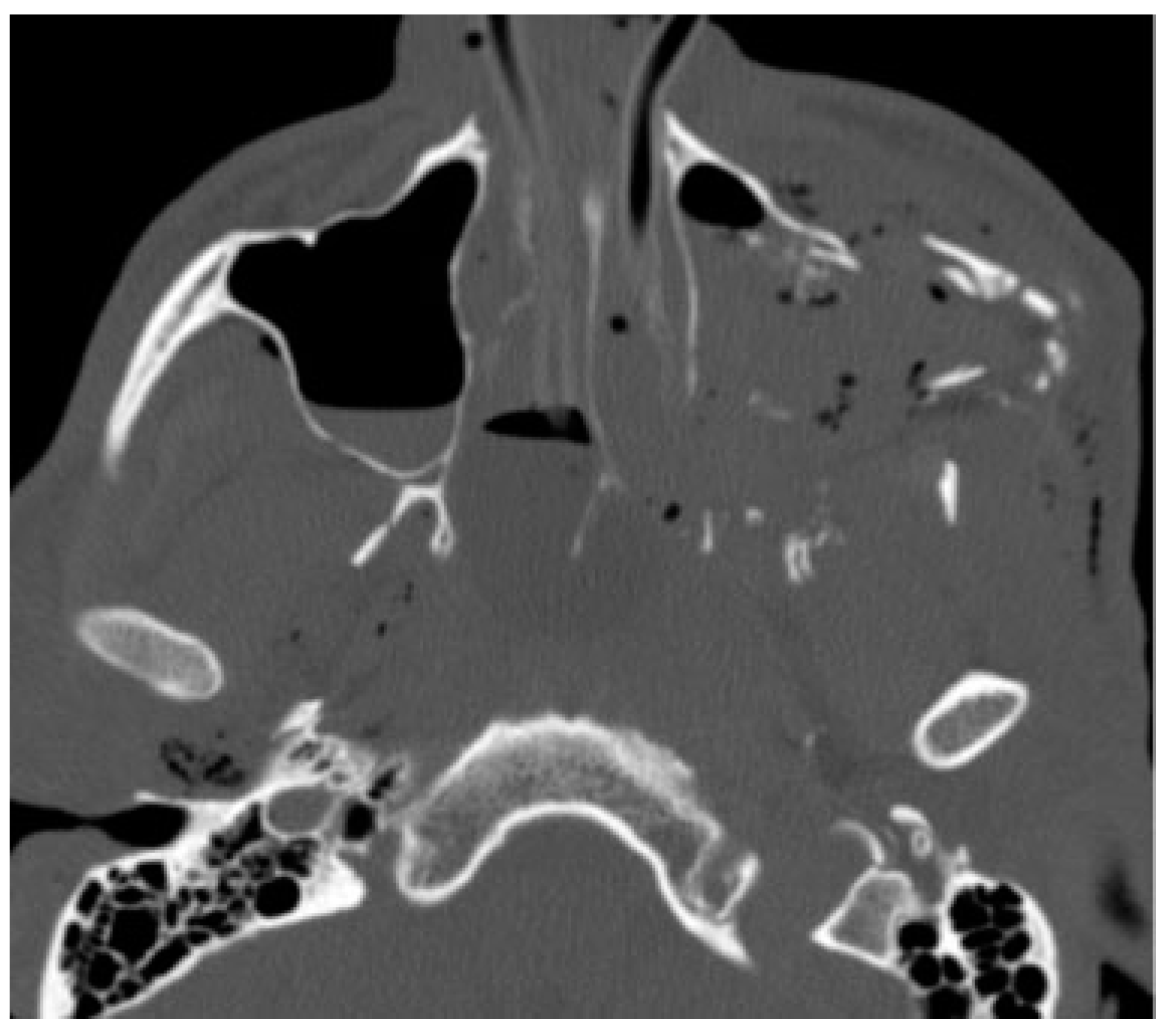

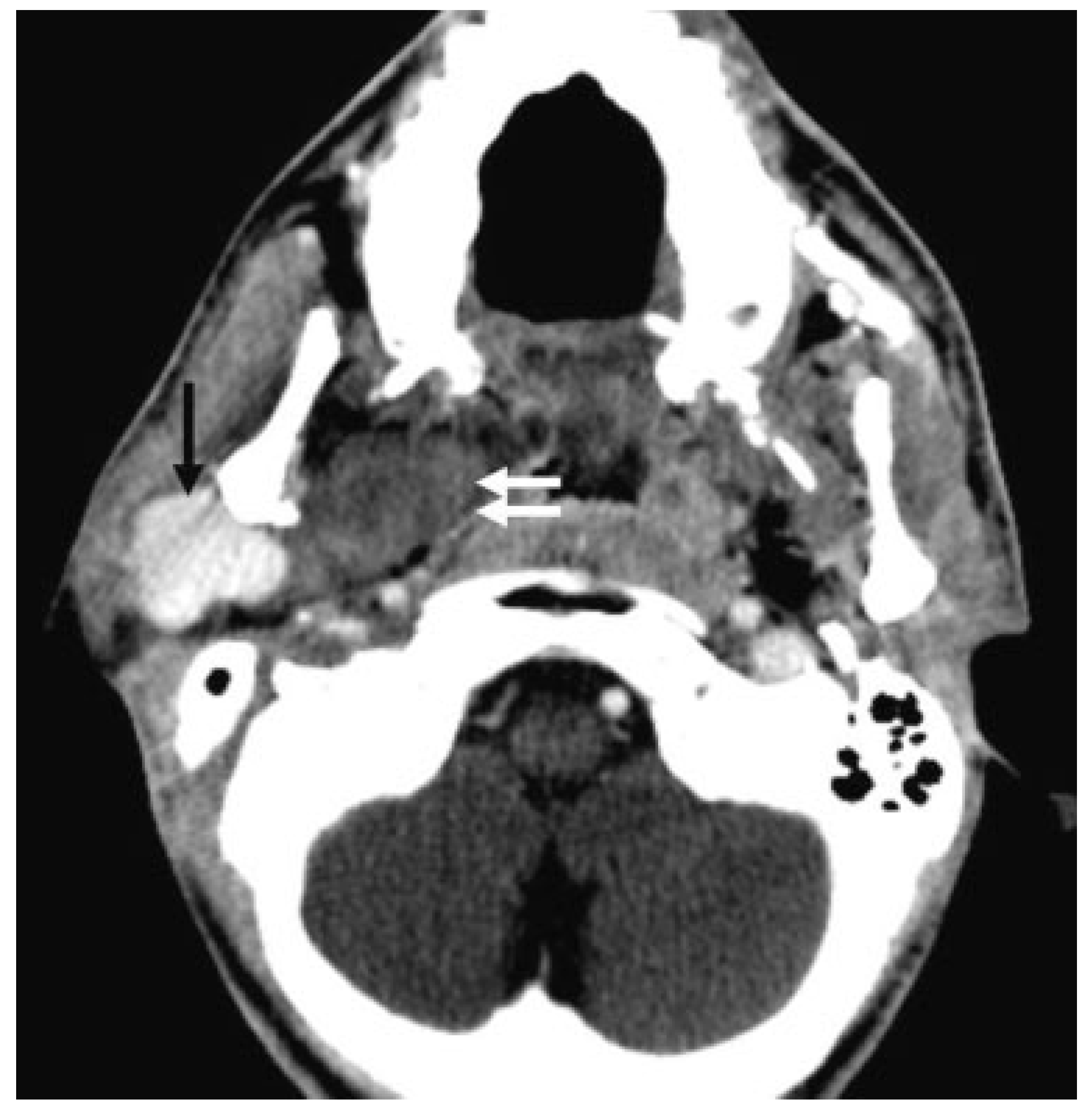

:Case Report

Discussion

Conclusion

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zachariades, N.; Skoura, C.; Mezitis, M.; Marouan, S. Pseudoaneurysm after a routine transbuccal approach for bone screw placement. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2000, 58, 671–673. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, D.G.; Marashi, A.; Malik, A. Pseudoaneurysm of internal maxillary artery secondary to gunshot wound managed by endovascular technique. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004, 62, 500–502. [Google Scholar]

- Zachariades, N.; Rallis, G.; Papademetriou, G.; Papakosta, V.; Spanomichos, G.; Souelem, M. Embolization for the treatment of pseudoaneurysm and transection of facial vessels. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2001, 92, 491–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.S.; Sy, E.D.; Chang, C.W.; Chang, S.S. Craniofacial gunshot injury resulting in pseudoaneurysm of the left internal maxillary artery and Collet-Sicard syndrome. J Craniofac Surg 2009, 20, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- dos Santos Pereira, R.; de Souza Guimaraes, V.C.; Timóteo, C.A.; Homsi, N.; da Rocha HVJr Hochuli-Vieira, E. Internal maxillary artery pseudoaneurysm subsequent gunshot wound in a teenager. J Craniofac Surg 2014, 25, 1125–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, Z.A.; Malis, D.D.; Wilson, J.W. Pseudoaneurysm of the maxillary artery after a stab wound treated by endovascular embolization. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007, 65, 790–794. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- D’Orta, J.A.; Shatney, C.H. Post-traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the internal maxillary artery. J Trauma 1982, 22, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heiserman, J.E.; Dean, B.L.; Hodak, J.A.; et al. Neurologic complications of cerebral angiography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1994, 15, 1401–1407, discussion 1408–1411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sliker, C.W.; Shanmuganathan, K.; Mirvis, S.E. Diagnosis of blunt cerebrovascular injuries with 16-MDCT: accuracy of whole-body MDCT compared with neck MDCT angiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008, 190, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, E.; Sugimoto, K.; Yanaka, K.; et al. Giant aneurysm of the superficial temporal artery. Case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol 2000, 53, 543–545. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buckspan, R.J.; Rees, R.S. Aneurysm of the superficial temporal artery presenting as a parotid mass. Plast Reconstr Surg 1986, 78, 515–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodanapally, U.K.; Dreizin, D.; Sliker, C.W.; Boscak, A.R.; Reddy, R.P. Vascular injuries to the neck after penetrating trauma: diagnostic performance of 40and 64-MDCT angiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2015, 205, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2016 by the author. The Author(s) 2016.

Share and Cite

Gold, M. Partially Thrombosed Internal Maxillary Pseudoaneurysm After Gunshot Wound. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2016, 9, 335-337. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0036-1582454

Gold M. Partially Thrombosed Internal Maxillary Pseudoaneurysm After Gunshot Wound. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2016; 9(4):335-337. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0036-1582454

Chicago/Turabian StyleGold, Menachem. 2016. "Partially Thrombosed Internal Maxillary Pseudoaneurysm After Gunshot Wound" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 9, no. 4: 335-337. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0036-1582454

APA StyleGold, M. (2016). Partially Thrombosed Internal Maxillary Pseudoaneurysm After Gunshot Wound. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 9(4), 335-337. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0036-1582454