Complex syndromic craniosynostosis has traditionally been managed with either fronto-orbital advancement or total cranial vault remodeling. Over the past 6 years, posterior cranial vault distraction (PCVD) has become an important technique in the initial management of complex craniosynostosis [

1,

2].

This technique has been shown to increase intracranial volume, treat intracranial hypertension, and improve the aesthetic contour of the posterior cranium [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. When compared with conventional cranial vault remodeling, distraction osteogenesis can provide a greater degree of expansion, partially due to the ability of the technique to progressively stretch the softtissue envelope [

4]. The presence of the distractors throughout the consolidation period increases the bony stability, which leads to a lower relapse rate [

1,

3,

8].

A review of posterior vault distraction literature from 2009 to 2013 showed that the average operative age for children undergoing this procedure was 16 months [

9]. Recently, the trend has moved toward performing PCVD prior to 1 year of age [

4]. In this study, we aim to show that PCVD can safely be performed as early as 3 months of age for the initial management of complex syndromic craniosynostosis.

Methods

Patients and Data Collection

A retrospective chart review was performed of all the patients treated with PCVD at Primary Children’s Hospital in Salt Lake City, Utah, between September 2012 and December 2014. Inclusion criteria for the study were a diagnosis of multisuture craniosynostosis and reconstruction with a posterior vault distraction procedure followed by adequate postoperative craniometric assessments. Patient demographic information was compiled, including patient age, prematurity, sex, diagnosis, and comorbidities. Operative age was corrected for prematurity. Operative details, including procedure time, estimated blood loss, and blood transfusion requirements, were documented and reviewed. Each patient’s distraction protocol details were recorded, including duration of latency, activation, and consolidation phases, distraction distance achieved, and postoperative complications. Occipital frontal head circumferences (OFCs) were recorded pre- and postdistraction, and at 3- and 6-month follow-up examinations.

Operative Technique and Distraction Protocol

Several variations of the posterior vault distraction technique have been published previously [

1,

2]. Our technique is briefly described here. With the patient in prone position with the neck extended, the posterior vault was approached through a bicoronal incision. An en bloc parietooccipital craniotomy was performed. The bone flap was left in place, attached to the underlying dura. Linear, radial barrel-stave osteotomies approximately 2 cm in width and 4 cm in height were made circumferentially in the lateral and posterior vault, below the level of the en block parietooccipital craniotomy. The barrel-staves were out-fractured at the base in green stick manner. Two internal distractors, one on each side, were positioned equidistantly between the vertex and the base of the parietooccipital craniotomy bone flap. Three-millimeter screws were used to secure the footplates of the distractors to the underlying bone (

Figure 1). Distractor extension arms were attached and brought out in the anterior scalp flap and the bicoronal incision was closed.

Each patient underwent a similar distraction protocol consisting of latency, activation, and consolidation periods. The full distraction distance allowed by the device was the endpoint for the activation phase. Following a 2-month average consolidation period, the distractors were removed. Postremoval evaluation and monitoring consisted of clinical assessments at 3 and 6 months.

Results

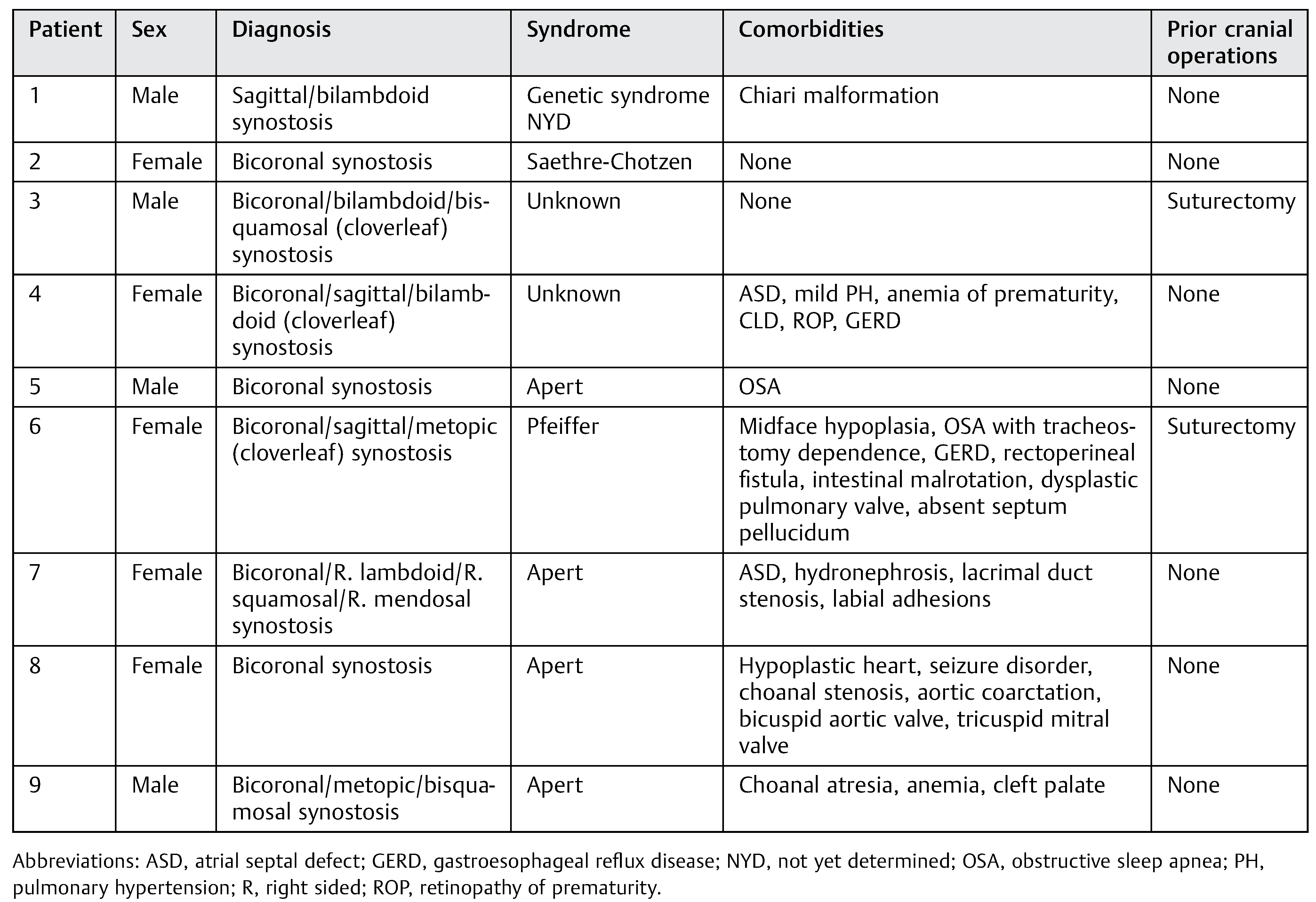

During the study time period, a total of nine children, four males and five females, with syndromic, multiple-suture synostosis underwent PCVD at our institution and met inclusion criteria. The indication for surgery in all cases was imminent elevation in intracranial pressure due to cranial vault restriction. For seven of the nine patients, this was the initial cranial vault procedure. The remaining two patients had cloverleaf deformities and underwent prior suturectomies shortly after birth for initial relief of elevated intracranial pressure (

Table 1).

All patients underwent PCVD in the first year of life. Of the nine patients, only four were born at term. The average gestational age at delivery was 35.4 weeks (range: 27–40 weeks). The corrected age at the time of surgery was 21.4 weeks (range: 12–38 weeks). The average operative time was 148 min (range: 90–186 min) and average estimated blood loss was 92.2 mL (range: 50–175 mL). Seven of the nine patients received a blood transfusion intraoperatively (

Table 2).

Each patient underwent a similar distraction protocol. A latency period of 3 to 4 days preceded the activation. During the activation phase, distraction occurred at a rate of 1 mm/day. The average duration of activation was 22.3 days (range: 14–28 days). The final consolidation period averaged 96.9 days (range: 54–227 days) (

Table 2).

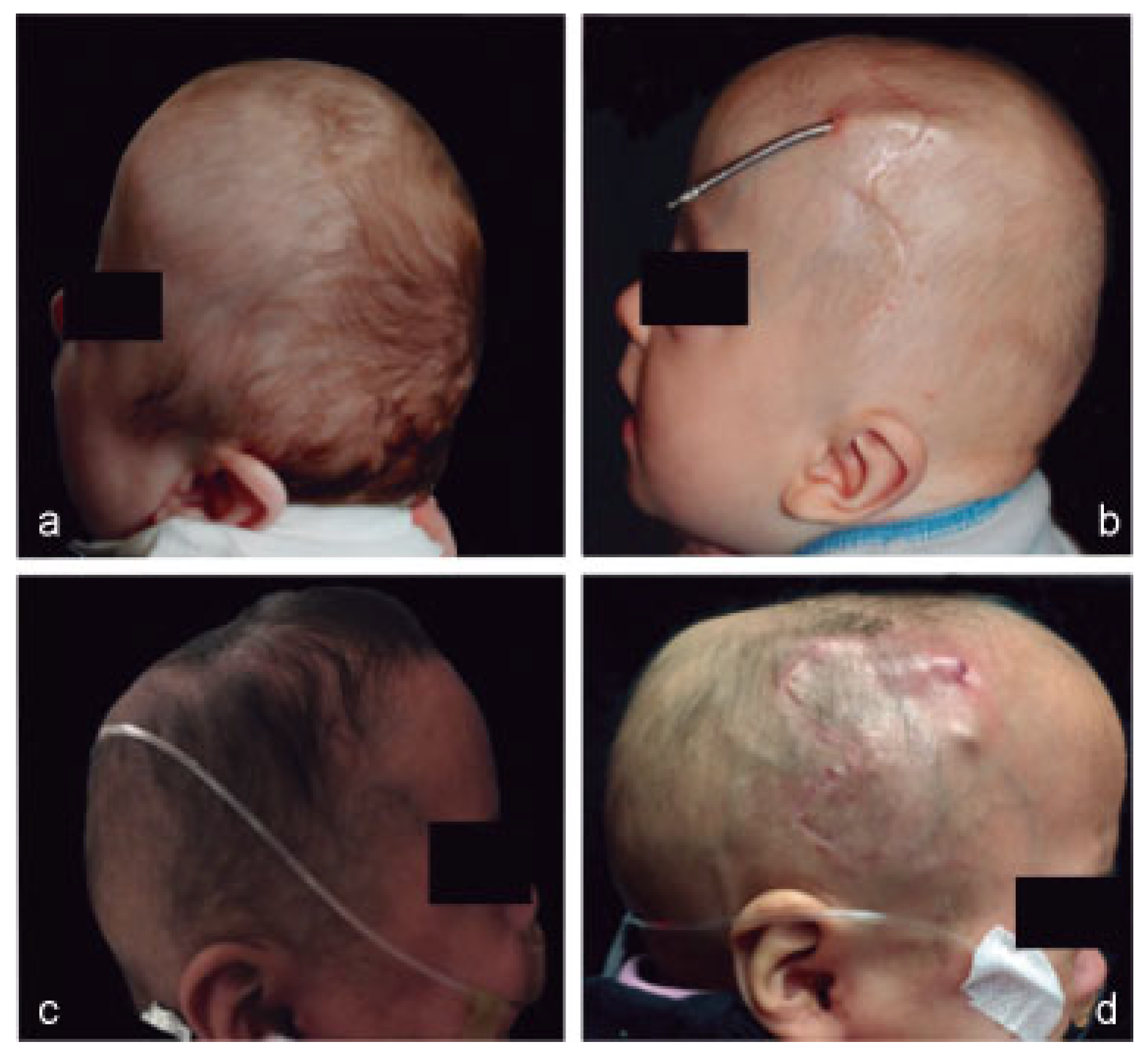

All patients had a substantial increase in head circumference with subjective improvement of the posterior calvarium shape (

Figure 2). The overall linear distracted distance averaged 26.3 mm (range: 20–30 mm). The average increase in OFC from preoperative to postdistraction was 4.9 cm (range: 1.5–6 cm). All patients showed developmental improvement following the procedure. Each patient was followed up closely after removal of the distractor hardware. At 3 months postoperative, an average OFC increase of 0.6 cm was seen from postdistraction measurements (range: 0–3 cm). At 6 months postoperative, an average increase of 0.5 cm was seen from 3-month measurement (range: 0–1 cm). Subjective posterior calvarium shape remained greatly improved for all patients (

Table 3).

Postoperative complications occurred for two patients. One patient experienced severe infection of the hardware after 22 days of activation and required operative washout and intravenous antibiotics for the duration of the consolidation phase. Another patient suffered a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak that prompted the premature termination of the activation phase (at 14 days) and placement of a lumbar drain.

Discussion

In 2009, White et al. published the first case series reporting the results of PCVD for the treatment of increased intracranial pressure in children with syndromic, multisuture craniosynostosis [

1]. Since that time, PCVD has gained popularity as the initial procedure in this patient population to increase intra-cranial volume and improve the aesthetic appearance of the posterior cranium [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. The ability to treat intracranial hypertension, which 35 to 80% of children with syndromic craniosynostosis will develop, has also made PCVD valuable surgical option [

10].

While posterior vault distraction has been shown to adequately treat increased intracranial pressure by significantly improving intracranial volume, there was initial concern about performing this operation in children younger than 6 months secondary to lack of adequate bone thickness for placement and retention of the distractor devices [

2]. However, more recent studies have shown that distraction can be performed adequately, without significant increase in device failure, on patients younger than 6 months [

4,

5,

6].

In this study, all but one patient were 6 months of age or younger, with our mean operative age 21.4 weeks, as adjusted for prematurity. The decision to adjust for prematurity was made after reviewing the guidelines and recommendations regarding the care of premature infants published by the American Academy of Pediatrics [

11]. These guidelines state that a premature child’s growth and development should be monitored based on corrected age until at least 24 months’ corrected age as their degree of growth more closely correlates with corrected age than actual age [

11,

12]. Therefore, the quality of calvarial bone present is better determined by corrected age than actual age. In addition, the operative age was corrected for prematurity given its association with risks for surgical and anesthetic.

In 2015, Greives et al. published a review of the literature on PCVD from 2009 to 2013, specifically looking at complications [

9]. Out of the 11 case studies reviewed, 30% of the 86 patients had complications. The most common complication was CSF leak/dural injury (9.8%), while pin infection/wound dehiscence/exposure was second (6.9%); 5.8% of patients suffered device failure [

9]. Our complication rate of 22% was comparable to the previously mentioned literature review. While two of the nine patients in our study had complications, neither of these was related to device failure, as might be a concern with the younger patient population. In addition, only the patient with CSF leak had to stop distraction prior to reaching the desired distraction distance. The patient who developed the pseudomonal infection was managed with washout and intravenous antibiotics, allowing the consolidation to be fully completed prior to removal of the distractor hardware.

The average increase in occipital frontal circumference of 4.9 cm seen in this series, along with the continued OFC improvement seen at 3- and 6-month follow-ups, shows the effectiveness of PCVD in increasing head circumference and thereby intracranial volume in this young patient population. The subject improvement in posterior vault aesthetics also complications that could have potentially impacted the outcomes seen in this study [

13]. supports the use of this procedure as the initial management for complex, multisuture craniosynostosis (

Figure 2). In addition, the safety of PCVD is demonstrated by the lack of intraoperative complication and the manageable postoperative complications experienced by our patients.

Conclusion

PCVD is an effective procedure in the management of complex craniosynostosis and appears to be a safe option very early in life with complication rates similar to older children.