Abstract

Historically, periodic academic meetings held by surgical societies have set the stage for discussion and exchange of ideas, which in turn have led to advancement of clinical practices. Since 2007, the AONA State of the Art: Facial Reconstruction and Transplantation Meeting (FRTM) has been organized to provide a forum for specialists around the world to engage in open conversation about the approaches currently at the forefront of facial reconstruction. Review of registration data of FRTM iterations from 2007 to 2015 was performed. The total number of participants, along with their level of medical training, location of practice, and medical specialty, was recorded. Additionally, academic programs and 2015 participant feedback were evaluated. From 2007 to 2011, there was a decrease in the overall number of participants, with a slight increase in the number of clinical specialties present. In 2013, a sharp increase in total participants, international attendance, and represented clinical specialties was observed. This trend continued in 2015. Adjustments to academic programs have included reorganization of lectures and optimization of content. FRTM is a unique forum for multidisciplinary professionals to discuss the evolving field of facial reconstruction and join forces to accelerate progress and improve patient care.

In the short and eventful history of reconstructive surgery, the open exchange of new ideas, accomplishments, and discoveries has been responsible for progress and advancement in the field. In addition, it has endorsed the development of consensus and standards of acceptable practice, allowing those less exposed and experienced to “catch up” with their forerunner and innovator peers. These efforts of surgical innovators have occasionally led to the foundation of surgical societies, focused on the growth of their particular area of practice and the creation of an open, congenial environment where like-minded individuals can work together to improve the outcomes of their patients.

What is now the American Academy of Otolaryngology— Head and Neck Surgery began during a meeting held by Hal Foster in Kansas City, MO, in 1896 [1]. Almost two decades later, William Shearer argued that “surgeons with a special interest in plastic surgery should join together to form an organization in which they might exchange ideas and experiences and help educate others…” [2]; his efforts led to the creation of the American Association of Oral Surgeons in 1921 [3]. As the interests of plastic surgeons grew broader, “Oral” was gradually replaced by “Plastic” and the American Association of Plastic Surgeons (AAPS) adopted its current name [4]. Around the same time the AAPS was rebaptized, Jacques Maliniac formed a parallel group, the Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, now the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS). Curiously and, in retrospect, quite appropriately, only 40% of the initial membership consisted of plastic surgeons; ophthalmologists, otolaryngologists, dermatologists, and oral surgeons all joined in the interest of cementing this burgeoning new specialty [5].

The widened interests of the AAPS and ASPS resulted in an understandable divergence. Carl Wadron and Casper Epsteen, who still gravitated toward the original maxillofacial scope of the AAPS, formed the American Society of Maxillofacial Surgeons (ASMS) shortly after the Second World War; peculiarly, this also took place in Kansas City, MO [6]. Across the Atlantic and shortly thereafter, a group of Swiss general and orthopaedic surgeons formed the Association for Osteosynthesis (AO) in an effort to improve the operative treatment of long bone fractures [7]. The AO broadened its aims in 1974, and began the study and widespread instruction of improved techniques of maxillofacial fracture repair. Also around this time, the first international societies dedicated to the blossoming techniques of microvascular tissue transfer were formed (International Society of Reconstructive Microsurgery, International Microsurgical Society). All of these groups met periodically, leading to considerable growth and achievement in separate, specific areas of reconstructive surgery.

A fascinating consequence of the regular assembly of colleagues and collaborators with common interests has been the development of new surgical specialties and subspecialties. A prime example is the short but important history of the Biennial Tissue Homotransplantation Conference, organized by John Marquis Converse and Blair Rogers. Over seven iterations, the conference brought together inquisitive minds from widely varying chosen fields of training and practice to discuss the common interest of transplantation [8,9]. Eventually, The Transplantation Society was formed [10], and the specialty’s brave history of innovation continued to flourish into the 21st century with the first successful face transplant in France [11].

Face transplantation has the unique character to both attract and require experts from an extensive array of medical and surgical specialties; the history of branching and separation of several of these fields was briefly described earlier. Craniofacial, maxillofacial, head and neck, microvascular, and transplant surgeons now coming together to achieve excellence in facial reconstruction is proof that a multidisciplinary team can accomplish much more than the sum of its parts. Furthermore, it is a tribute to the initial proponents of reconstructive surgery that representatives from all of the specialties who were born from their early meetings and discussions have come full circle, back to their facial reconstruction roots. This remarkable achievement reignited efforts toward the development of a multidisciplinary meeting with a single focus: the difficult problem of facial reconstruction.

In the late 1980s, craniofacial surgeons set out to develop criteria for Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) certification of Craniofacial Fellowships, emphasizing the potential of the specialty for congenital, traumatic, and post-oncologic deformities in children and adults, involving bone and soft tissues. Even though a curriculum was approved by the ASMS, ACGME certification was pursued only by a few programs, mainly because of the extra work involved in—and reimbursement difficulties resulting from—the certification process. Thereafter, an annual symposium was sponsored by the ASMS and eventually cosponsored by the ASPS; the main goal was to promote the subspecialty to residents, who received substantial reductions in tuition. Despite financial support from Dr. Dennis Nigro’s Fresh Start foundation, the course was discontinued due to growing expenses and declining profits, particularly in comparison to otherwise very profitable aesthetic surgery courses. An attempt was made to rekindle interest in the subject by requesting AO North America (AONA) sponsorship, with hopes that representation from a broad spectrum of specialties involved in facial reconstruction would provide a sufficient audience to sustain interest in the course.

We present the senior author’s (EDR) experience in organizing and implementing the biennial State of the Art: Facial Reconstruction and Transplantation meeting (FRTM). Prompted by a suggestion from Paul N. Manson in 2005, and in partnership with AONA, the meeting has been held five times, from 2007 to 2015. We discuss participant demographics, curriculum design, and the importance of providing as much flexibility and expansion as does our rapidly evolving field.

Methods

At the request of the authors, AONA generously provided the registration information and academic program for each iteration of the biennial State of the Art: Facial Reconstruction and Transplantation meeting held from 2007 to 2015.

Based on data provided upon enrollment, different parameters were analyzed to identify participant demographics. The total number of attendees for each FRTM was calculated. Furthermore, participants were categorized according to their level of medical training (attending, fellow, resident, operating room personnel, or other, which includes medical students). Participants’ primary practice location was also recorded and divided into three categories: United States, Canada, or outside North America. Finally, the number of medical specialties represented in each course was calculated, along with the amount of participants within each specialty.

The academic program of each course was reviewed to identify changes in curriculum design from the FRTM’s inception to its most recent iteration. Finally, participant feedback and evaluation of the course, collected at the conclusion of the 2015 meeting, was assessed to identify overall satisfaction and possible areas for improvement.

Results

Total Attendance and Level of Medical Training

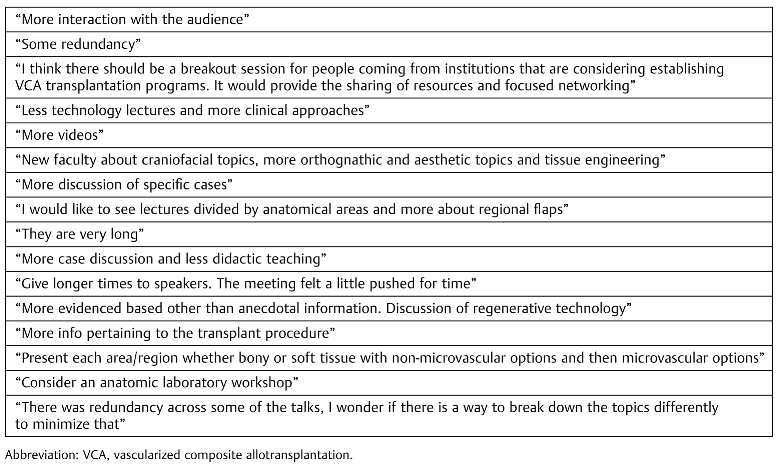

The number of participants was calculated for each year the FRTM was conducted (range: 69–264). Figure 1 shows the distribution of the total participant per year, according to reported level of medical training. A decline in total attendance was observed from 2007 to 2011; however, in 2013 and 2015, there was a marked increase in total number of participants as well as number of participants from each training-level category. The number of total participants almost tripled from 2011 to 2013, and there was nearly a fourfold increase from 2011 to 2015. Participation trends at the attending level mirrored that of total attendance, while resident participation was superior to attending participation in 2009 and 2011.

Figure 1.

Number of participants in each category of medical training. Total number of participants per each year is included.

Practice Location

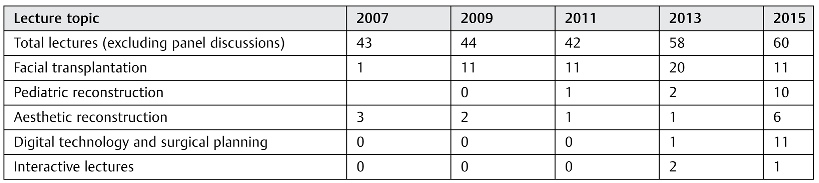

There was also an increase in international presence among participants from 2009 to 2015 (Figure 2). Within this timeframe, there was an eightfold increase in participants who primarily practice outside North America. U.S. participation has followed the trend of total attendance previously described.

Figure 2.

Number of participants practicing in United States, Canada, and outside North America.

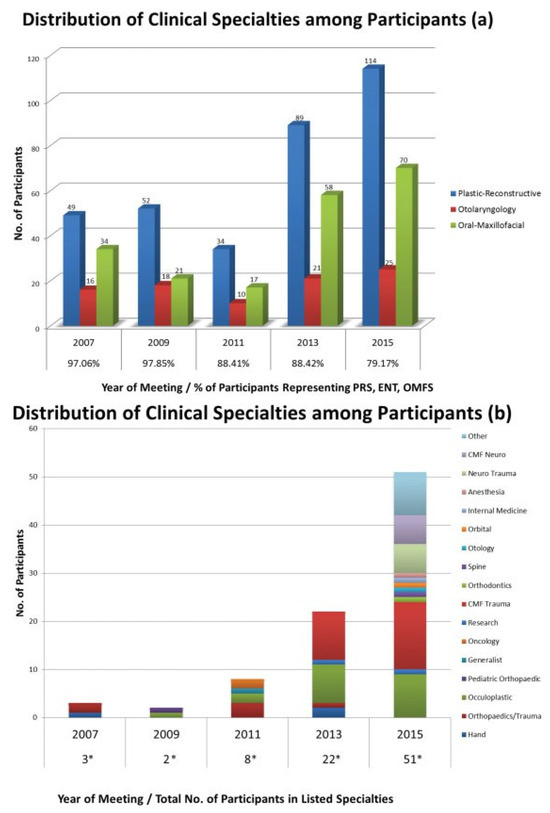

Medical Specialties Represented

In 2007 and 2009, the vast majority of the audience (97%) comprised plastic–reconstructive surgeons (PRS), otolaryngologists (ENT), and oral-maxillofacial surgeons (OMFS) (Figure 3a), with a slight decrease to 88% in 2011 and 2013. In 2015, however, despite an overall increase in the absolute number of participants from these specialties, they represented only 79% of total participants. This was the result of an increase in the heterogeneity of attendee specialties (Figure 3b). In 2011 and 2013, there were only four and five specialties, respectively, other than PRS, ENT, and OMFS. In 2015, a total of 12 specialties other than PRS, ENT, and OMFS represented in the audience, with a total of 51 participants pertaining to these specialties. Five of these specialties are nonsurgical.

Figure 3.

(a) Number of participants representing plastic–reconstructive surgery (PRS), otolaryngology (ENT), and oral-maxillofacial surgery (OMFS) is shown. Percentage of participants in these three specialties is indicated below the year of meeting. (b) Number of clinical specialties other than PRS, ENT, and OMFS represented each year. Asterisk (*) indicates number of participants from specialties other than PRS, ENT, and OMFS per year.

Participant Feedback and Course Evaluations

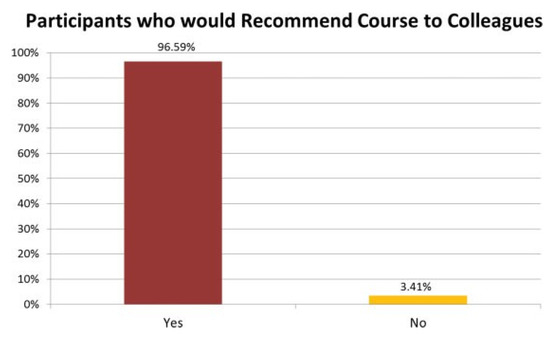

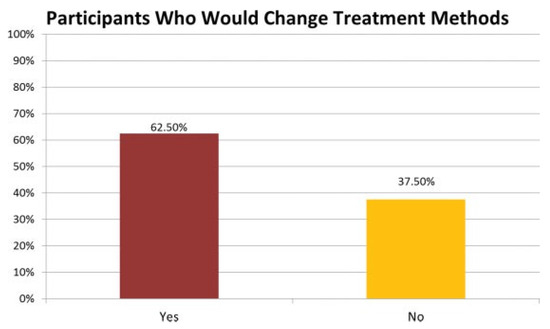

Eighty-eight participants responded to survey evaluations. Almost two-thirds of respondents (64%) rated the FRTM as 5/ 5; 33% rated it as 4/5, with 97% of respondents reporting they would recommend the course to a colleague (Figure 4). Among respondents, 62.5% reported they would change their method of treatment as a result of attending the FRTM (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Percentage of survey respondents who reported they would recommend the course to their colleagues.

Figure 5.

Percentage of survey respondents who reported they would change treatment of their patients after attending the course.

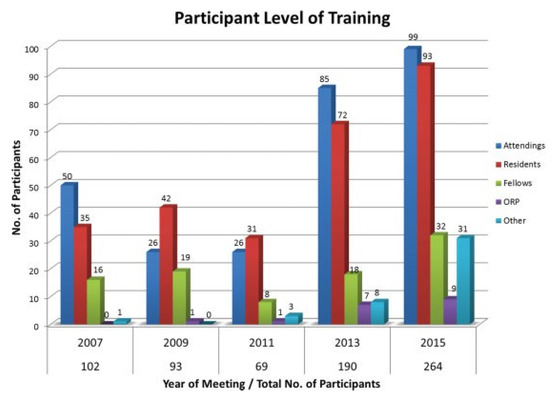

In the form of invited written feedback, participants reported topics from nearly all lectures to be beneficial; additional constructive comments were also noted (Table 1). Finally, when asked to address barriers participants could anticipate would interfere with the application of practices learned in the FRTM, the most common concern was cost (27/88 respondents).

Table 1.

Selected participant feedback on lectures.

Academic Programs and Course Content

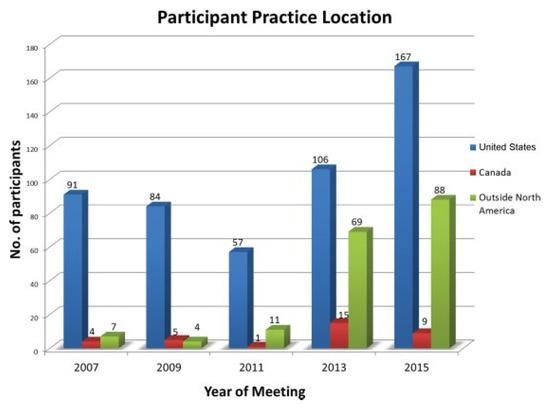

The inaugural FRTM in 2007 focused on didactic presentations related to craniomaxillofacial reconstruction, separated by anatomical regions, lasting 2.5 days. A single 20-minute lecture discussed the future role of facial transplantation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of lectures dedicated to selected topics.

The curriculum in 2009 followed a similar outline, with the same duration and many returning speakers; however, the first half-day of the course was dedicated to the topic of facial transplantation: institutional experiences, immunological considerations, and a single lecture on ethical challenges.

The FRTM made several changes in 2011. Lectures were organized into sessions, based on subject matter, with expert moderators designated to each session. Additionally, there were a greater number of lectures specifically concerning microsurgical reconstructive techniques; however, microsurgical treatment options are always examined in lectures that focus on the reconstruction of a particular anatomical location. An entire session devoted to expert surgeons discussing the management of complications and improvement in outcomes was introduced.

Numerous alterations to the course were seen in 2013, beginning with an increase in its duration to 3 full days. The topic of facial transplantation dominated the first full day’s program, with a larger number of groups reporting on international experience, and the number of lectures on the topic nearly doubled (Table 1). Moreover, a multidisciplinary group of panelists were invited to discuss their opinions on facial transplantation. An additional first in 2013 was the inclusion of one lecture with a specific focus on technology and surgical planning. A novel 1-hour interactive panel discussion of complicated cases was introduced to present the role of transplantation in facial reconstruction.

During the FRTM’s latest iteration in 2015, the lectures related to facial transplantation were distributed throughout the first 2 days of the program; however, the amount of lectures on the topic decreased by nearly 50% compared with the previous assembly (20 in 2013, 11 in 2015). Furthermore, the panel session on the role of transplantation was expanded: experienced surgeons now discussed problematic clinical cases presented and expressed personal preferences on whether they considered those patients to be good candidates for facial transplantation. Another component of previous programs that was extended was expert advice on managing complications and handling challenging clinical presentations. This session lasted a full hour, compared with shorter discussions in previous years. A new session of five lectures was devoted to pediatric reconstruction alone, with five other presentations on pediatric topics interspersed throughout the weekend’s program. Similarly, a new session of six lectures was dedicated to aesthetic craniofacial reconstruction. Additionally, two whole sessions specifically discussed digital technology (11 lectures).

Discussion

We present the evolution of the biennial State of the Art: Facial Reconstruction and Transplantation meeting over the course of 8 years and five iterations. Numerous specialty and subspecialty societies related to reconstructive surgery hold academic meetings on an annual basis. Yet, these meetings are either focused on very specific aspects of facial reconstruction (e.g., bone, soft tissues) or they cover all aspects of broad surgical specialties, which makes the content related to facial reconstruction a small part of the program. This is quite understandable, as meetings should match the missions and goals of each society and the wide interests of their membership. However, similar to how the founders of the AAPS felt that they required a more pertinent setting than the American Medical Association’s annual session (Section of Stomatology),4 we believe that a meeting dedicated solely to facial reconstruction is a fitting stop in the academic calendar/circuit.

A major difference between the FRTM and Converse’s Tissue Homotransplantation conference is the innovative nature of the latter’s field of study; the vision to establish a periodic congregation of pioneers in an entirely new area was key to the progress of transplantation. The practice of facial reconstruction is centuries old, and the creation of the FRTM is a testament to the difficult challenge it continues to present to surgeons everywhere. The main analogy between the two series of meetings is encouraging, however: multidisciplinary experts and learners coming together to discuss a single problem, regardless of specialty training or society membership. This will no doubt be conducive to further progress. Looking back, prior to the end of WWII, the ASPS’ main function was to serve as a facilitator for meetings [5], and great things have come from providing the right forum for reconstructive surgeons. In the case of the FRTM, it has been critical that the AONA has provided an ideal forum for multiple disciplines to learn from each other and about the evolving field of facial reconstruction.

Attendance to the FRTM has fluctuated over the years, with 2011 presenting the lowest number of participants (Figure 1). There was a sharp increase in total attendance in 2013, and the events that transpired between both meetings may have played a role in that increase. In the 10 years since the first face transplant was performed, one could argue that every year has been full of important developments, but 2012 stands out as a breakthrough year for the field. Long-term outcomes of the first face transplant recipient were published that year [12], as were a landmark case series of full-face transplant recipients [13] and a detailed report on full-face transplant surgical technique [14]. Furthermore, the highest number of face transplants per calendar year (seven) was performed in 2012 [15,16,17,18]. These events certainly generated interest in the facial reconstruction community for 2013, and contributed to the positive cycle of growth that led to an even higher attendance in 2015. Of note, the number of international attendees has also grown substantially since 2011, with the fifth and most recent iteration of the course hosting more global visitors (97) than any other (Figure 2). Increasing the international scope of the meeting was also a priority for the Tissue Homotransplantation conference [19]. In keeping with the multidisciplinary origins of plastic and reconstructive surgery [5], great attention has been placed to establish the FRTM as a forum for all relevant specialties. As early as WWI, the importance of interspecialty collaboration and a team approach was known, as evidenced by Vilray Blair’s historic maxillofacial team at Walter Reed Hospital, which included oral surgery, ENT, ophthalmology, neurosurgery, and prosthetic dentistry, among others [3]. The FRTM has included presenters from these and many other specialties, such as orthodontics, ethics, and transplant surgery. More importantly, there has been steady growth in the number of different specialties present in the audience (Figure 3b). Furthermore, while 97% of attendees in 2007 were either plasticreconstructive, oral-maxillofacial, or otolaryngology—head and neck surgeons, representatives from these specialties traditionally associated with facial reconstruction added up to only 79% of total attendance in 2015 (Figure 3a). We hope to continue to design programs that attract specialists from these and other disciplines involved in reconstruction and transplantation.

We were delighted to find that 97% of 2015 participants would recommend FRTM to their colleagues (Figure 4), and as the result of their attendance, 63% would change previous treatment methods of their practices (Figure 5). This highlights that participants are overall satisfied with the course; moreover, it embodies their motivation to update clinical decision making based on the experience and evidence presented by leaders in facial reconstruction. The directors of the FRTM recognize that to maintain this positive impact and emulate the evolving nature of facial reconstruction, continuous improvements are necessary. Constructive participant feedback offers an excellent guide for improvement (Table 1). For its next iteration, based on these comments, the lecture program will reduce redundancy in topics and discussions through better grouping of lectures by focus. After a strong series of related lectures in 2015, the digital technology session has been shortened now that participants have been exposed to available resources. Moreover, the topics of aesthetic reconstruction and possibilities in tissue engineering will be expanded. Suggestions to include anatomic/cadaver workshops are common and seriously considered, yet they present considerable logistical obstacles. We recognize that there is enormous potential in adding tissue laboratory sessions to practice new and complicated surgical procedures described during lectures, bridging the gap between theoretical discussions and hands-on learning. The FRTM is designed to be as inclusive as possible for all of our reconstructive colleagues, and addresses facial reconstruction regardless of mechanism of injury, as lecture programs cover congenital deformities as well as defects that are a result of trauma, burns, and post-oncologic resection, in addition to the aesthetic principles to be considered during repair (Table 2).

A recent survey of the American Council of Academic Plastic Surgeons identified the ten most important plastic surgery innovations of the 20th century; eight of these are consistently included in the academic program of the FRTM (myocutaneous flaps, microsurgery, craniofacial surgery, skin grafting, transplantation, distraction osteogenesis, fat grafting, and rigid fixation of fractures/osteotomies) [20]. The same survey listed the ten most important plastic surgery innovations of the modern era, and six of these are closely related to facial reconstruction and are also a large part of the FRTM curriculum (face transplantation, fat grafting, biologic scaffolds, tissue engineering, perforator flaps, and noninvasive imaging) [20]. As new techniques and technologies come to the fore, we are confident that the FRTM will remain the right forum for open discussion and determining their potential roles in facial reconstruction.

During the fifth Tissue Homotransplantation Conference, introductory remarks by Hilary Koprowski have proven prophetic: “If this series of biennial meetings continues, and if the general rate of progress in this particular field is maintained, the future feats of plastic surgery may exceed those envisioned by the wildest imagination.” [21]. If we as a community indeed continue to congregate and share our experiences, milestones, and pitfalls, to the benefit of our patients, we can echo these remarks in our challenging chosen field of practice. We take this opportunity to encourage our colleagues and collaborators, from all disciplines, who are interested and involved in facial reconstruction to join us at the AONA State of the Art: Facial Reconstruction and Transplantation meetings, as we are slowly but surely becoming an unofficial international society of learners and educators in the field.

References

- Papel, I.D.; Goldstein, J.C. Centennial celebration of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery in the United States: History of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996, 114, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McDowell, F. History of the American Association of Plastic Surgeons, to 1963. Plast Reconstr Surg 1963, 32, 240–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randall, P.; McCarthy, J.G.; Wray, R.C. History of the American Association of Plastic Surgeons, 1921-1996. Plast Reconstr Surg 1996, 97, 1254–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deranian, H.M. The transformation of the American Association of Oral Surgeons into the American Association of Oral and Plastic Surgeons. J Hist Dent 2008, 56, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hait, P. History of the American Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons, Inc. 1931-1994. Plast Reconstr Surg 1994, 94, 1A–109A. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.R.; Juhala, C.A.; Manson, P.N.; Crawley, W.A.; Jacobs, J.S. History of the American Society of Maxillofacial Surgeons: 1947-1997. Plast Reconstr Surg 1997, 100, 766–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matter, P. History of the AO and its global effect on operative fracture treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1998, 347, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Converse, J.M.; Rogers, B.O. Introduction. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1957, 64, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, B.O.; Converse, J.M. A review of the conference on the relation of immunology to tissue homotransplantation. Plast Reconstr Surg (1946) 1954, 14, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilney, N.L. Four decades of international cooperation, innovation, growth and progress. Transplantation 2006, 81, 1475. [Google Scholar]

- Dubernard, J.M.; Lengelé, B.; Morelon, E.; et al. Outcomes 18 months after the first human partial face transplantation. N Engl J Med 2007, 357, 2451–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzo, P.; Testelin, S.; Kanitakis, J.; et al. First human face transplantation: 5 years outcomes. Transplantation 2012, 93, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomahac, B.; Pribaz, J.; Eriksson, E.; et al. Three patients with full facial transplantation. N Engl J Med 2012, 366, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomahac, B.; Pribaz, J.J.; Bueno, E.M.; et al. Novel surgical technique for full face transplantation. Plast Reconstr Surg 2012, 130, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorafshar, A.H.; Bojovic, B.; Christy, M.R.; et al. Total face, double jaw, and tongue transplantation: An evolutionary concept. Plast Reconstr Surg 2013, 131, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roche, N.A.; Vermeersch, H.F.; Stillaert, F.B.; et al. Complex facial reconstruction by vascularized composite allotransplantation: The first Belgian case. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2015, 68, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özel, A.S.; Güçlü, Z.A.; Gülşen, A.; Özmen, S. The importance of the condition of the donor teeth and jaws during allogeneic face transplantation. J Craniofac Surg 2015, 26, 1338–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifian, S.; Brazio, P.S.; Mohan, R.; et al. Facial transplantation: The first 9 years. Lancet 2014, 384, 2153–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Converse, J.M.; Rogers, B.O. Fifth tissue homotransplantation conference. Introductory remarks. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1962, 99, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultman, C.S.; Friedstat, J.S. The ACAPS and SESPRS surveys to identify the most influential innovators and innovations in plastic surgery: No line on the horizon. Ann Plast Surg 2014, 72, S202–S207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koprowski, H. Introductory remarks. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1957, 64, 735. [Google Scholar]

© 2016 by the author. The Author(s) 2016.