Abstract

Anterolateral thigh (ALT) free flap is a common flap with multitude of indications. The purpose of this article is to review the reconstructive indications of the flap in head and neck defects. This is a retrospective study of 194 consecutive ALT flaps. Data including patient characteristics (age, sex, comorbidities), disease characteristics (histology, T stage), and flap characteristics (size of the flap, type of closure of ALT donor site) were collected. The outcome in terms of flap success rate, surgical, and donor site morbidity were studied. A total of 194 flaps were performed in 193 patients over a period of 10 years. Mean age of the patients was 55 years (range 16–80 years). Out of the 193 patients, 91 (47.1%) patients had oromandibular defects, 52 (26.9%) had tongue defects, 15 (7.7%) had pharyngeal defects, 17 (8.8%) had skull base defects, 4 (2%) had scalp defects, and 14 (7.2%) had contour defects of the neck. The overall flap success rate was 95.8% (8 total flap loss out of 194). Hypertrophic scar was the commonest donor site problem seen in 20 (10.3%) patients. This study shows the versatility of free ALT flap in head and neck reconstruction. It is a reliable and safe. Donor site morbidity is minimal.

The anterolateral thigh (ALT) free flap was first described in 1984 by Song et al. [1]. Wei et al. popularized this flap [2]. They reported 672 cases of ALT flap reconstruction with minimal failure rate (2% total and 3% partial failure). Kimata et al. described the versatility of the flap in head and neck reconstruction and also noted that the donor site morbidity is minimal [3,4]. An ideal soft tissue free flap for head and neck reconstruction should have the following characteristics, versatility in design, adequate tissue, appropriate texture, minimal donor site morbidity, availability of diverse tissue types on one pedicle, potential for reinnervations, long pedicle, feasibility of a two team approach, and consistent anatomy for easy and safe flap dissection [5,6,7]. Except for the latter, the ALT flap has been suggested to have all the qualities. The purpose of this article is to discuss the various reconstructive indications, outcome, and morbidity of ALT flap reconstruction in head and neck.

Methods

This is a retrospective study of 194 consecutive ALT free flaps used for head and neck reconstruction in a tertiary level academic cancer center. The study period was between January 2004 and March 2013. The electronic medical records including operative details, clinical, and follow-up details were studied. Data including patient characteristics (age, sex, comorbidities), disease characteristics (benign/malignant, histology, Tstage), and flap characteristics (size of the flap, type of closure of ALT donor site) were collected. The outcome in terms of flap success rate and complications including surgical morbidity and donor site morbidity were studied. The reconstructive indications of the free ALT flap were studied by classifying the defects broadly into (1) oromandibular defects, (2) tongue, (3) pharyngeal, (4) skull base, (5) cranial/scalp, and (6) contour defects of neck (►Table 1).

Results

A total of 194 ALT flaps were performed in 193 patients over a period of 10 years for head and neck reconstruction. Mean age of the patients was 55 years (range 16–80 years). Majority of the patients (80%) were males; 125 patients had oral cavity defects; 17 patients had tumors arising from paranasal sinuses; and 16 patients had oropharyngeal defects. Other primary sites included laryngopharynx, calvarium, parotid gland, thyroid gland, and facial skin. The flap was used mainly for T4 defects (51.2%) but was also used for T2/T3 defects (30.2%).Two patients had T1 lesions, one was a posterior oral tongue lesion associated with adjacent leukoplakia and the other had a retromolar trigone lesion with associated submucous fibrosis and trismus. ►Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics including the sites of the primary, T size and the reconstructive indications. The flap size ranged from 30 to 375 cm2. Large scalp defects and combined neck and pharyngeal defects will require larger flaps. The case with 375 cm2 size had a recurrent cancer of the buccal mucosa involving the mandible, maxilla, cheek mucosa, and skin including neck.

Table 1.

Primary tumor and defect characteristics.

Table 1.

Primary tumor and defect characteristics.

| No. of patients (n ¼ 193) | Percentage | |

| Site | ||

| Oral cavity | 125 | 64.7 |

| Oropharynx | 16 | 8.2 |

| Nasopharynx | 2 | 1 |

| Larynx and hypopharynx | 11 | 5.6 |

| Nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses | 17 | 8.8 |

| Neck, face and scalp | 18 | 9.3 |

| Others | 4 | 2 |

| Type of defect | ||

| Oromandibular | 91 | 47.1 |

| Tongue | 52 | 26.9 |

| Pharynx | 15 | 7.7 |

| Skull base | 17 | 8.8 |

| Calvarial/scalp | 4 | 2 |

| Contour defects of the neck | 14 | 7.2 |

| T stage of primary | ||

| T1 | 2 | 1 |

| T2 | 35 | 18.1 |

| T3 | 43 | 22.1 |

| T4 | 99 | 51.2 |

| Benign lesions | 6 | 3.1 |

| Osteoradionecrosis | 2 | 1 |

| Details not available | 6 | 3.1 |

The donor site was primarily closed in 64% of patients and needed skin grafting in 36% of patients. There was partial loss in six patients and total flap loss in eight patients. Of the flaps lost, two flaps were used for tubed reconstruction of pharyngeal defects and six flaps for oral cavity and cheek reconstruction. In eight patients with total flap loss, four patients were salvaged with pectoralis major myocutaneous flap (PMMC), two had free radial forearm flap (RFFF) and in one patient, the defect was salvaged with contralateral ALT free flap. In one patient, an obturator was used to rehabilitate the defect. Of the six patients with partial loss in the form of skin necrosis, two defects healed with conservative management, two required skin grafting, one required PMMC flap, and one was repaired with a RFFF. The partial loss occurred in those flaps used for full-thickness cheek defects (four flaps) and in two flaps used for floor of mouth and buccal mucosa. Twenty-two patients underwent re-exploration procedures for vascular insufficiency. Five of these patients had venous thrombosis, four had arterial problem, five had both arterial and venous problem, five had venous congestion due to external factors such as hematoma, kinking, and three patients had negative re-exploration. The three patients with negative re-exploration had minimal flap congestion in the postoperative period, but on reexploration no pathology could be identified and the flaps survived. Fourteen patients could be salvaged by timely intervention. Fifty-three patients received radiotherapy and 47 received chemoradiotherapy as adjuvant treatment. In 66 (34.1%) patients, the flap was done in salvage procedures with a history of previous radiotherapy. The overall flap success rate was 95.8(8 flap loss out of 194). Donor site morbidity included partial skin graft loss in 15 (7.7%) patients. Total skin graft loss was noted in 8 (4.1%) patients. Twenty (10.3%) patients had hypertrophic scar. ►Table 2 shows primary and donor site morbidity details.

Four flaps had to be modified on table due to vascular deficiencies of the flap identified in the initial exploration of the pedicle. Three of these cases were modified to include the tensor fascia lata (TFL) pedicle. This is possible by increasing the superior extent of the skin paddle. In one case, the skin paddle was modified to make it an anteromedial thigh flap.

Discussion

We report a single institutional experience with the free ALT reconstruction in 193 patients undergoing 194 flaps for head and neck defect reconstruction. The versatility of ALT free flap in head and neck reconstruction is already reported. Ross et al. had used this flap for intraoral defects in 18 patients including anterior tongue, floor of mouth, posterior tongue, and retromolar trigone but the authors cautioned against the use of thin ALT flap [7]. Disa et al. had used the flap in lateral skull base defect [8]. Omer Ozkan et al. used free ALT for scalp defects in 11 patients [9]. Demirkan et al. described the use of ALT flap in fullthickness defects of the mandible, full-thickness defects of the cheek, and other defects in their series of 59 patients [10].

Table 2.

Primary and donor site morbidity.

Table 2.

Primary and donor site morbidity.

| Numberof patients | Percentage | |

| Primary site | ||

| Partial flap loss | 6 | 3 |

| Total flap loss | 8 | 4.1 |

| Oro/pharyngocutaneous fistula | 14 | 7.2 |

| Hematoma | 8 | 4.1 |

| Donor site | ||

| Partial graft loss | 15 | 7.7 |

| Total graft loss | 8 | 4.1 |

| Wound dehiscence | 7 | 3.6 |

| Wound infection | 7 | 3.6 |

| Hypertrophic scar | 20 | 10.3 |

As evident from our study, ALT flap can be used over a range of head and neck defects in different sites and subsites. This is obvious from the range of size of the flap (30–375 cm2) used and that the flap was used for defects arising out of the resection of tumors from T stages T2 to T4. Large scalp defects and combined neck and pharyngeal defects will require larger flaps. Flap success in our series was 95.4% which is comparable to previously reported rates (95–98%) [4,10,11,12]. Flaps could be salvaged after re-exploration in 15 patients, which high-lights need for trained personnel and timely intervention. Major recipient site complications were seen in 24 patients (25%) which is again comparable to other reported series [10,11,12]. The donor site complications associated with this flap were minimal and majority of the donor sites could be closed primarily. Even though complications such as graft loss are seen in few patients, but these complications can be managed conservatively or with minimal surgical intervention. In this series, 36% of the patients required skin grafting at the donor site. This incidence is higher than that is reported in the literature. Generally, in donor size defects less than 7 to 8 cm in width, a primary closure is possible. But in cases where skin grafting was used, the flap dimensions were larger than this. The larger primary defect size, which is usual in cases of advanced oromandibular primaries, necessitated larger flaps.

The reconstructive indications of the flap can be summarized as follows.

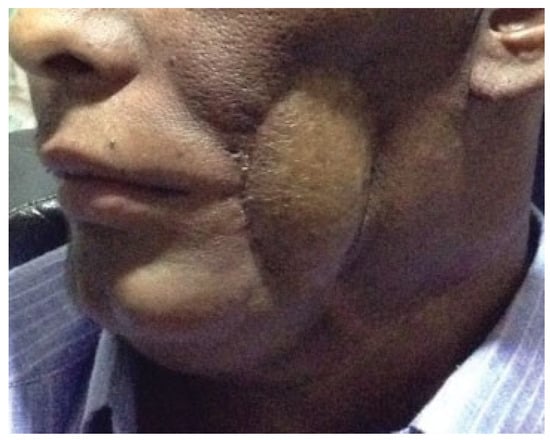

Oromandibular defects—ALT free flaps can provide complex multiaxial reconstruction of combined oromandibular defects with or without the loss of oral commissure. Bipaddling with a de-epithelialized segment in between or two paddles based on two perforators can simultaneously replace the lining and cover defects. The bulk of the flap including the muscle and fat can plug the infratemporal fossa defect which is usually associated with such defects. Commissure replacement though challenging is possible with the use of fascia lata extensions which can be tunneled through the remaining lip and fixed to contralateral side (►Figure 1).

In oromandibular defects, the usual practice is to use bone flaps. But the situations in which only soft tissue reconstruction was done include (1) severe preoperative trismus, which is very common in our patients due to submucous fibrosis and (2) elderly edentulous patients. The 91 patients included in this series of ALT flaps include such patients. When a bone flap was not used, the defect was not bridged with a plate. These patients had defects as a result of malignancy resection. Hence most of the patients would receive postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy. Plate with soft tissue reconstruction usually results in infection and extrusion of plate following radiotherapy.

Tongue defects—The flap can provide the bulk required for reconstructing larger tongue defects. Differential thinning can be used to provide the lateral sulcus in defects of tongue with the floor of mouth and marginal mandibulectomy defects. We have also tried motorizing the vastus lateralis muscle with anastomosis to the cut end of hypoglossal nerve in neck in three cases, but the long-term outcomes in terms of the improvement in tongue mobility is to be analyzed. ►Figure 2a,b shows a patient with T3 tongue tumor reconstructed with ALT flap.

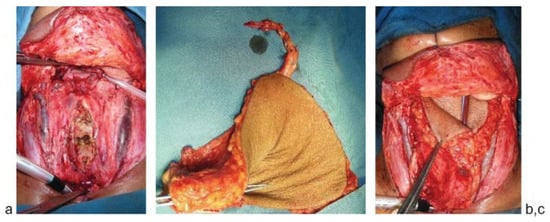

Pharyngeal defects—Abundance of tissue makes the flap suitable for pharyngeal defects, either circumferential or patch defects after laryngopharyngectomy. The under surface of the flap can be skin grafted in case the pharyngeal defects are associated with large skin loss. The disadvantage is the thickness of the flap, but it can be suitably thinned. The donor site morbidity compared with the RFFF is also less. ►Figure 3a–c shows a total laryngopharyngectomy with circumferential defect reconstructed with tubed ALT flap. Fifteen patients had pharyngeal defects following laryngopharyngectomy. The overall incidence of oro/pharyngocutaneous fistula was 76.2% (14 patients). Few of the patients had stricture especially in the lower anastomosis of the circumferential pharyngeal reconstruction. The exact number of the patients who had the stricture was not collected in this review.

Figure 1.

A patient with oromandibular defect with skin loss reconstructed with anterolateral thigh flap.

Figure 2.

(a) Oral tongue tumor staged as T3. (b) Reconstruction with anterolateral thigh flap.

Figure 3.

(a) Circumferential total laryngopharyngectomy defect. (b) ALT flap being tubed. (c) Tubed ALT flap being insetted for the defect. ALT, anterolateral thigh.

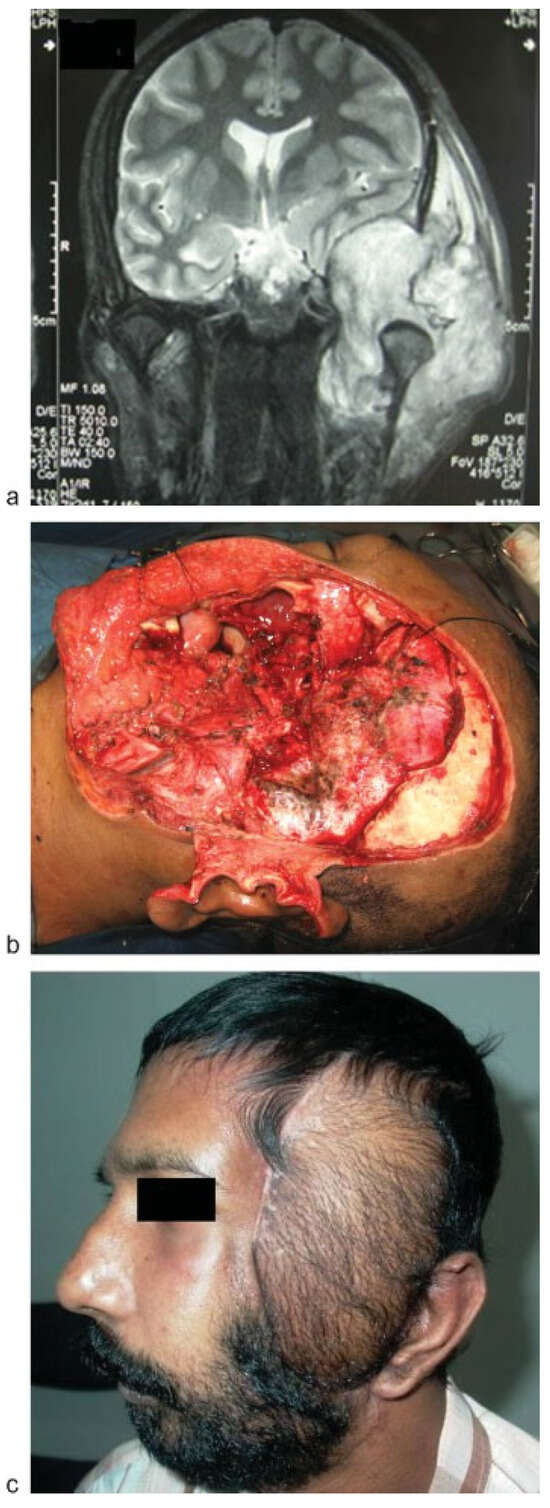

Skull base defects—Long pedicle with abundant muscle tissue makes it an ideal flap in skull base defects following craniofacial resections. Rectus abdominis flap which is the usual choice in this situation is limited by its short pedicle size. The donor morbidity of the ALT is also less compared with the rectus flap. ►Figure 4a–c shows a patient with adenoid cystic carcinoma of the lateral skull base. The defect was reconstructed with simultaneous double flaps using ALT and rectus abdominis flaps.

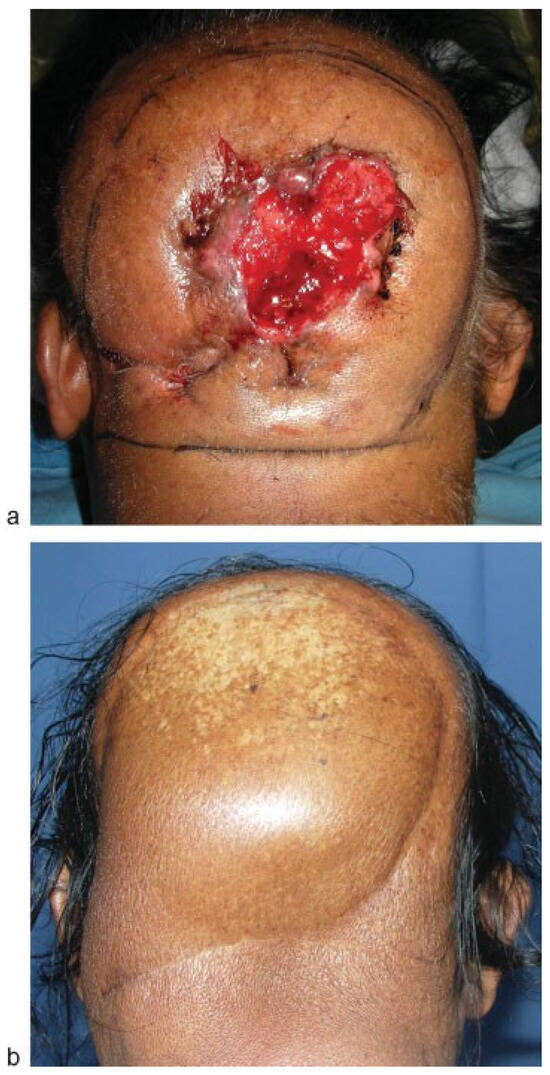

Calvarial/scalp defects—Long pedicle, the possibility of thinning and availability of large amount of tissue, makes it suitable for large calvarial/scalp defects. ►Figure 5a,b shows scalp squamous cell carcinoma resected and reconstructed with an ALT flap.

Contour defects of the neck—The muscle and fat tissue can replace the complex contour defects of the neck and face, including parotidectomy defects. In case of postirradiated neck defects after radical neck dissection, the flap can cover the exposed vessels, in the irradiated area to provide cover to great vessels and to replace the skin loss. In parotidectomy defects, the vastus lateralis muscle can be used to motorize the face in appropriate cases of facial nerve sacrifice. ►Figure 6 shows a patient with a parotidectomy with skin defect reconstructed with ALT flap.

ALT flap is versatile, pliable, and has potential for composite tissue replacement [13,14]. The versatility of the flap hinges on the ability to harvest multiple tissue components in various combinations; the reliable size and position of the perforators supplying the large skin paddle; and the long, wide-caliber pedicle. The flap harvest is convenient because it does not require patient repositioning and can be performed simultaneously using a two-team approach. The thigh donor site can be concealed easily, as it can be closed primarily and does not violate a functional motor unit and thus results in minimal morbidity [15]. Supplementary tissues such as iliac bone, tendon, fascia, or nerve may be reconstituted using suitable tissues raised in an “extended” anterolateral thigh flap based on the lateral circumflex femoral artery system [16]. The anterolateral thigh perforator flap may be divided to provide multiple tissue paddles, two smaller sized flaps raised from one thigh, or multiple flaps raised based on the lateral circumflex femoral artery to fill multiple defects using only one vascular anastomosis [17].

Figure 4.

(a) Magnetic resonance imaging scan of a patient with lateral skull base defect. (b) Lateral skull base defect showing the skull base, dura, oral mucosal, and skin defect. (c) The defect was reconstructed with simultaneous free rectus abdominis and ALT flap. ALT flap was used mainly for the skin cover. ALT, anterolateral thigh.

Modifications of ALT flap like the use of vascularized fascia lata sling for oral commissure reconstruction, motorized vastus lateralis muscle for total glossectomy reconstruction and differential thinning to contour the flap for tongue reconstruction have been used in our service. These modifications are not discussed in detail in the present article.

Figure 5.

(a) Patient with a scalp squamous cell carcinoma. (b) Reconstruction with anterolateral thigh flap.

Four flaps in the series had to be abandoned due to anatomical variations causing vascular deficiencies. There are reports in the literature regarding the anatomical variability of the flap. There have been concerns about the consistency of its vascular anatomy with occasional tiny cutaneous perforator which makes it difficult to dissect and because of its complicated distribution of vessels to the skin [12]. The skin and underlying musculature are largely supplied by the descending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery, which arises from the profunda femoris artery [2]. Although originally described as a free cutaneous flap based on a septocutaneous vessel, in fact, only 12 to 18% of anterolateral thigh flaps are septocutaneous and 80% are musculocutaneous perforators traversing the vastus lateralis [5,10]. Very rarely, there may be no suitable perforators on which to base a fasciocutaneous anterolateral thigh flap in which case the flap may be raised using the underlying vastus lateralis muscle as a carrier, extended medially as a “freestyle” free flap or laterally as a TFL flap, or the contralateral thigh is explored because vascular asymmetry is the rule [2,5].

Figure 6.

Parotidectomy with skin defect reconstructed with anterolateral thigh flap.

Conclusion

This study shows the versatility of free ALT flap in head and neck reconstruction. It is a reliable and safe. Donor site morbidity is minimal. Abundance of tissue including skin, muscle, and fat and the possibility of thinning has made it a suitable choice in varied indications in the head and neck.

References

- Song, Y.G.; Chen, G.Z.; Song, Y.L. The free thigh flap: A new free flap concept based on the septocutaneous artery. Br J Plast Surg 1984, 37, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, F.C.; Jain, V.; Celik, N.; Chen, H.C.; Chuang, D.C.; Lin, C.H. Have we found an ideal soft-tissue flap? An experience with 672 anterolateral thigh flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002, 109, 2219–2226, discussion 2227–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimata, Y.; Uchiyama, K.; Ebihara, S.; et al. Anterolateral thigh flap donor-site complications and morbidity. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000, 106, 584–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimata, Y.; Uchiyama, K.; Ebihara, S.; et al. Versatility of the free anterolateral thigh flap for reconstruction of head and neck defects. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997, 123, 1325–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimata, Y.; Uchiyama, K.; Ebihara, S.; Nakatsuka, T.; Harii, K. Anatomic variations and technical problems of the anterolateral thigh flap: A report of 74 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998, 102, 1517–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.S.; Thomas, S.; Chakrabati, A.; Lowe, D.; Rogers, S.N. Patient preference in placement of the donor-site scar in head and neck cancer reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008, 122, 20e–22e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, G.L.; Dunn, R.; Kirkpatrick, J.; et al. To thin or not to thin: The use of the anterolateral thigh flap in the reconstruction of intraoral defects. Br J Plast Surg 2003, 56, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disa, J.J.; Rodriguez, V.M.; Cordeiro, P.G. Reconstruction of lateral skull base oncological defects: The role of free tissue transfer. Ann Plast Surg 1998, 41, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozkan, O.; Coskunfirat, O.K.; Ozgentas, H.E.; Derin, A. Rationale for reconstruction of large scalp defects using the anterolateral thigh flap: Structural and aesthetic outcomes. J Reconstr Microsurg 2005, 21, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirkan, F.; Chen, H.C.; Wei, F.C.; et al. The versatile anterolateral thigh flap: A musculocutaneous flap in disguise in head and neck reconstruction. Br J Plast Surg 2000, 53, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mäkitie, A.A.; Beasley, N.J.; Neligan, P.C.; Lipa, J.; Gullane, P.J.; Gilbert, R.W. Head and neck reconstruction with anterolateral thigh flap. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003, 129, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shieh, S.J.; Chiu, H.Y.; Yu, J.C.; Pan, S.C.; Tsai, S.T.; Shen, C.L. Free anterolateral thigh flap for reconstruction of head and neck defects following cancer ablation. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000, 105, 2349–2357, discussion 2358–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chana, J.S.; Wei, F.C. A review of the advantages of the anterolateral thigh flap in head and neck reconstruction. Br J Plast Surg 2004, 57, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, Y.R.; Seng-Feng, J.; Kuo, F.M.; Liu, Y.T.; Lai, P.W. Versatility of the free anterolateral thigh flap for reconstruction of soft-tissue defects: Review of 140 cases. Ann Plast Surg 2002, 48, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, R.S.; Bluebond-Langner, R.; Rodriguez, E.D.; Cheng, M.H. The versatility of the anterolateral thigh flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009, 124 (6, Suppl), e395–e407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.H.; Wei, F.C.; Lin, Y.T.; Yeh, J.T.; Rodriguez, E.D.J.; Chen, C.T. Lateral circumflex femoral artery system: Warehouse for functional composite free-tissue reconstruction of the lower leg. J Trauma 2006, 60, 1032–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.C.; Chen, H.C.; Jain, V.; et al. Reconstruction of through-and-through cheek defects involving the oral commissure, using chimeric flaps from the thigh lateral femoral circumflex system. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002, 109, 433–441, discussion 442–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the author. The Author(s) 2015.