High-velocity injuries, such as those that stemming from a gunshot or industrial accident, can lead to the occurrence of an intraorbital foreign body [

1], often accompanied by penetrating ocular trauma [

2]. In such cases, the ophthalmic examination should begin with the documentation of visual acuity, followed by a detailed examination of the orbit for periorbital and subconjunctival hemorrhage and proptosis. Extraocular movements and visual fields should be examined and a careful inspection of the globe should be performed to determine the presence or absence of perforation [

3]. With advances in radiological techniques, such as high-resolution reconstruction computed tomography, the assessment of such injuries has become easier and more accurate [

4].

The retrieval of an intraorbital foreign body can be difficult because of the proximity of critical structures, such as the contents of the superior orbital fissure, the optic nerve, ethmoidal vessels, and cranial structures [

5]. Among the different approaches employed in the treatment of facial injuries, the coronal approach, which was popularized by Tessier, is one of the most versatile for midface surgeries [

6]. However, the large incision causes concern regarding the visible postoperative scar. Thus, several techniques have been described to minimize scar visibility, including a straight incision, coronal incisions, a gull-wing or W-shaped incision, and the use of six short linear incisions [

7].

This article describes the use of the temporal approach on a firearm victim in whom the breech of a rifle had impaled orbital region, with the extremity lodged in the infratemporal fossa.

1. Case Report

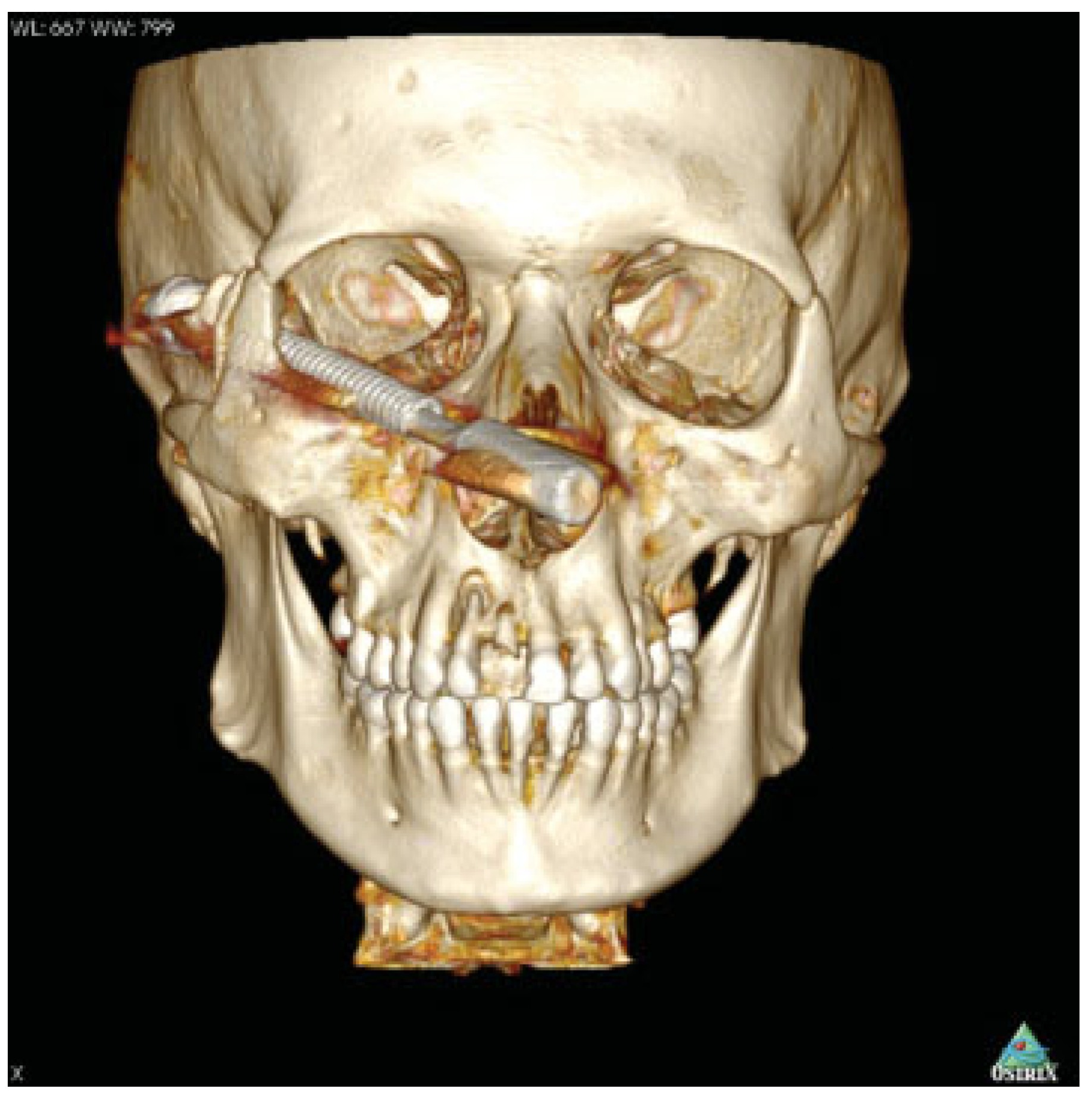

A 31-year-old male patient presented to the Regional Trauma Hospital in Campina Grande (state of Paraíba, Brazil) following an accident with the breech of a rifle, which had penetrated the right orbit 4 h earlier. The clinical examination revealed a metallic object protruding from the right infraorbital region that was palpable in the temporal region (

Figure 1). The patient reported the loss of visual acuity in the right eye because of trauma and reported having no visual impairment before the accident. The ophthalmologic examination using biomicroscopy demonstrated paralytic mydriasis, intact cornea, hyphema in the anterior chamber, lens in situ, and chemosis in the conjunctiva with hemorrhage. The funduscopic examination revealed inferior vitreous hemorrhage, retinal hemorrhage, detachment of the choroid and vitreous and papillary detachment.

The ophthalmologist declared that the contusion in the right ocular globe triggered important internal bleeding with irreversible injuries in internal structures, leading to blindness. Computed tomography with three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction revealed fractures of the zygomatic bone and right lateral wall of the orbit in the region of greater wing of the sphenoid bone (

Figure 2). The foreign body was a cylindrical metallic object that had passed through the right orbit, transfixed the greater wing of the sphenoid bone, and became lodged in the infratemporal fossa.

2. Surgical Technique for Temporal Access

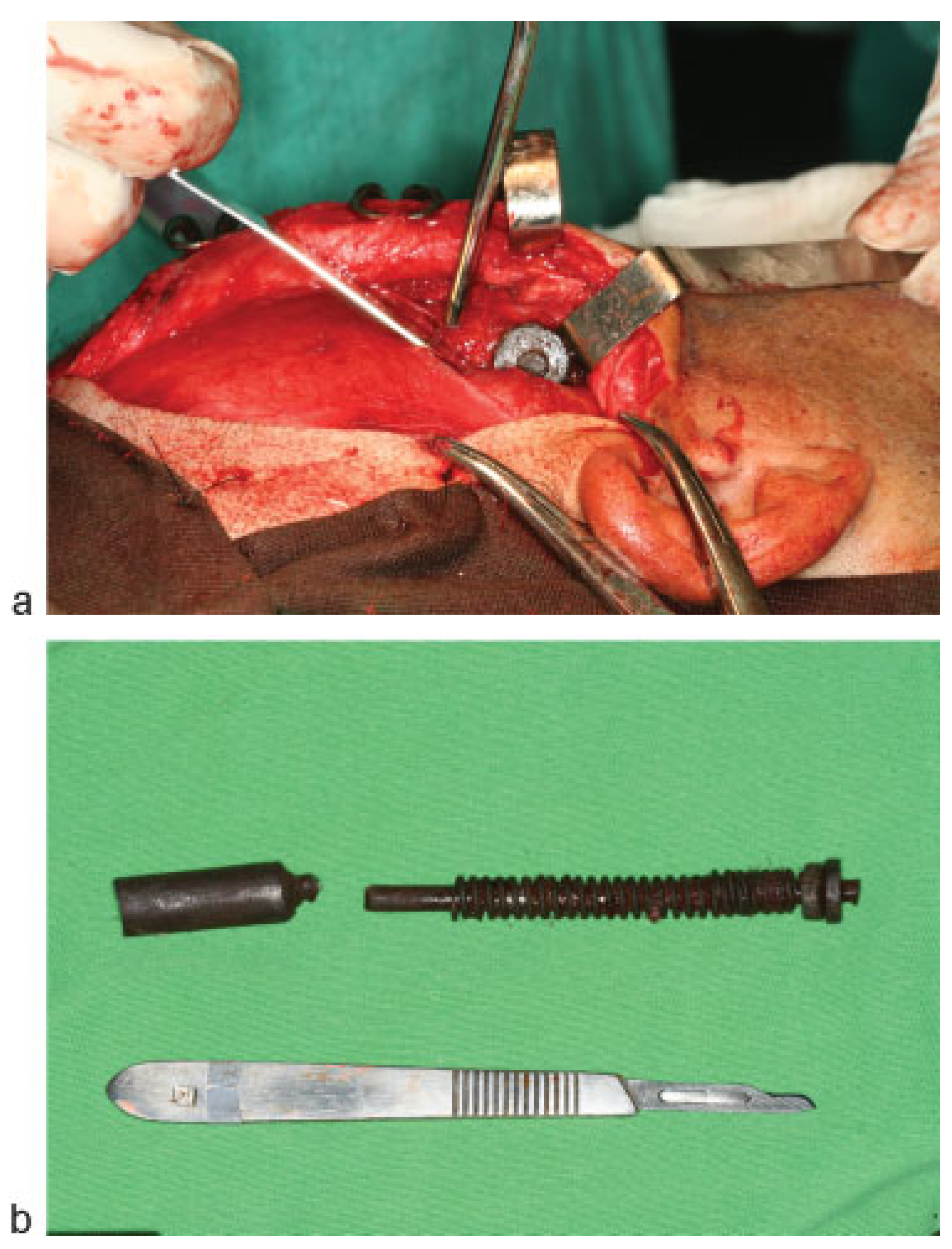

The patient was prepared for removal of the foreign body under general anesthesia. After cleaning and antisepsis with 2% chlorhexidine, local anesthesia was performed with an injection of Xylocaine and epinephrine (1:200.000). A curved incision curve was initiated 10 mm in front of the tragus, continuing through half the posteri- or–anterior extension and ending in the upper portion of the temporalis muscle (

Figure 3). The incision was made only to the superior temporal lines laterally, preventing penetration of the temporalis fascia to the temporalis muscle, which bleeds readily on incision. The flap was elevated on the subgaleal plane with a scalpel and a temporal fascia was incised 6 cm above the zygomatic arch. Dissection proceeded immediately through the inner side of the deep layer of temporal fascia. With the exposure of the metallic object (

Figure 4a), the surgical team cut the object into two pieces with cutter pliers for easy removal (

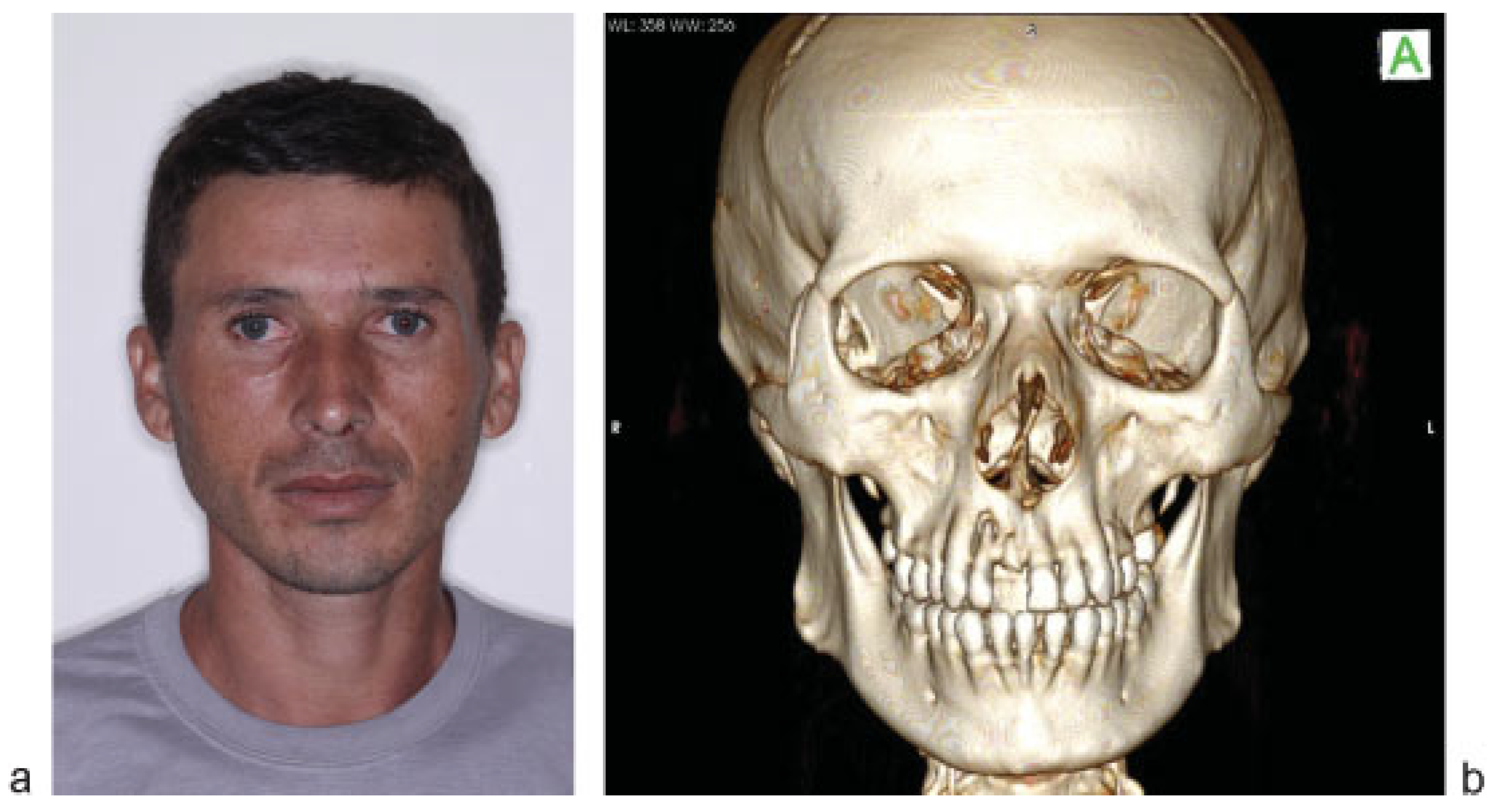

Figure 4b). Suturing of the surgical wound was performed with nylon 3.0, followed by the placement of pressure dressing. Immediately following recovery from anesthesia, a new ophthalmologic examination confirmed the loss of visual acuity, absence of pupillary reflexes and the maintenance of the movements of the extrinsic musculature of the eye. At the 1-year follow-up evaluation, the patient had an acceptable esthetic outcome and no complaints (

Figure 5a,b).

3. Discussion

The removal of a foreign body from the maxillofacial complex should involve careful planning. Surgical exploration without accurate preoperative localization is contraindicated due to the possibility of fragmentation, as incomplete removal of the material can lead to treatment failure. It is therefore essential to collect as much information as possible regarding the location of the object to determine the most appropriate surgical approach [

8]. Moreover, a multidisciplinary team is needed for orbital injuries caused by a foreign body, as accurate neurological and ophthalmic examinations are required before the surgical removal of the object. Computed tomography with 3D reconstruction allows the precise localization of the object and the determination of the proper surgical approach. In the case described herein, the ophthalmologist was essential to the diagnosis of the loss of visual acuity loss and 3D computed tomography allowed the determination of the most appropriate surgical approach.

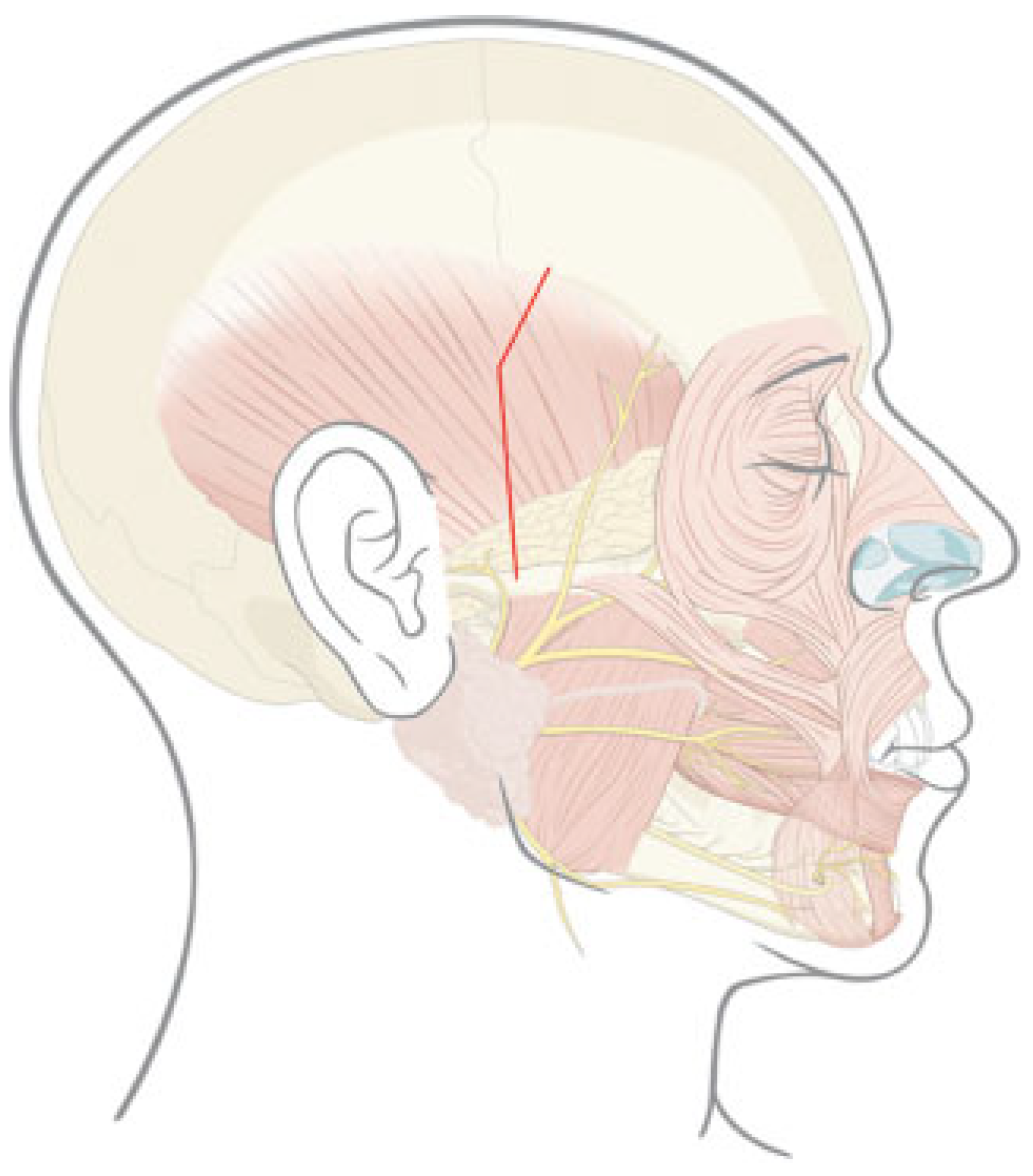

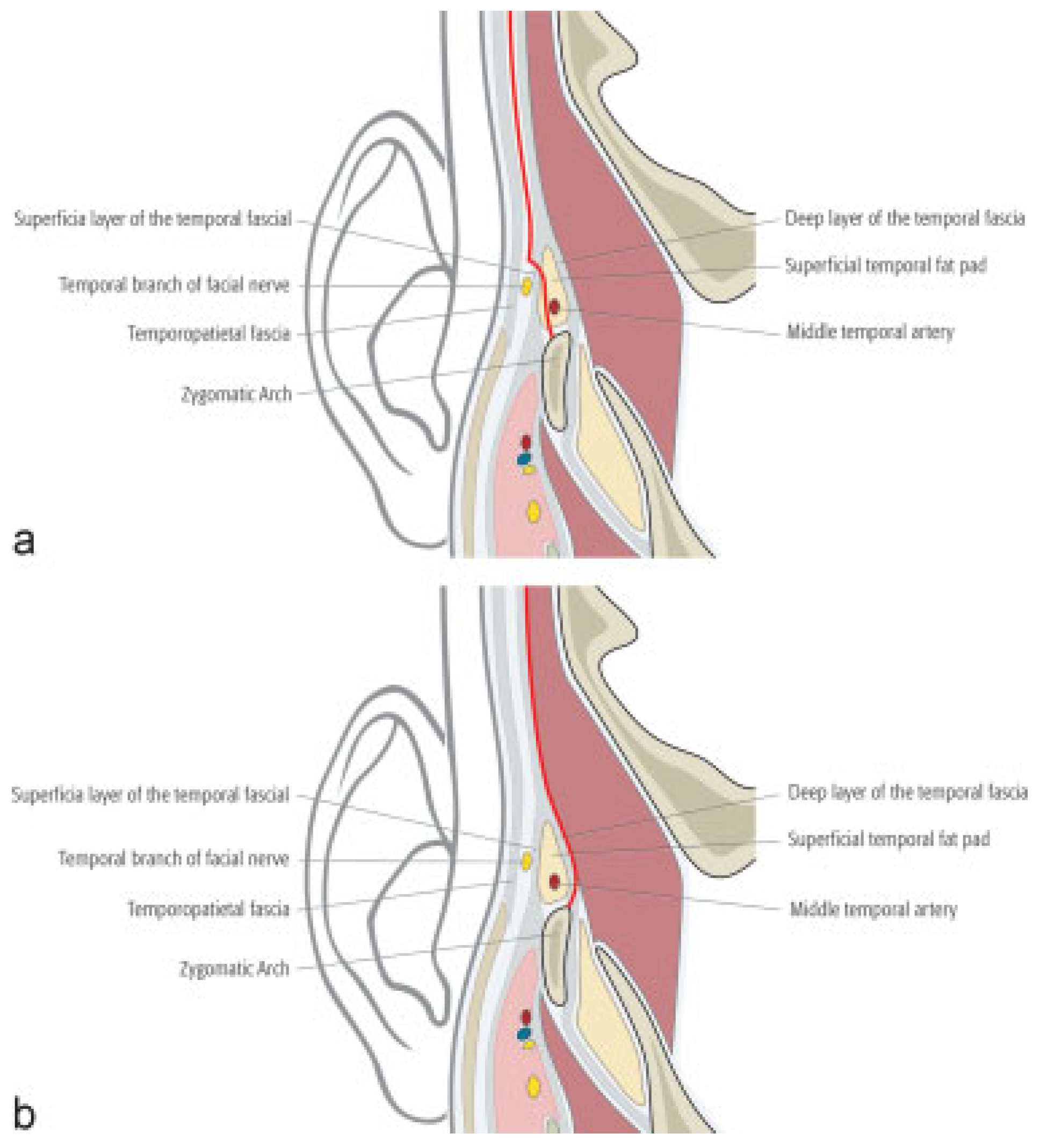

The coronal approach is required for wider access to the orbital roof, frontorbital region or naso-orbital-ethmoid complex and facilitates circumferential exposure. The main drawbacks of the coronal approach are the size of the incision, the extensive dissection, and complications such as alopecia, forehead numbness and injury to the temporal branch of the facial nerve (

Figure 6a) [

9,

10]. Luo et al, developed a novel coronal access, denominated the supratemporal access, and compared it with the traditional coronal access regarding the rate of complications, especially injuries to the temporal and zygomatic branches of the facial nerve (

Figure 6b). The authors modified the coronal access through a subcutaneous incision 5 to 6 cm above the zygomatic arch in the temporal fascia and the dissection proceeded through the inner side of the deep layer of the temporal fascia. With the conventional access, the incision is 2 to 3 cm above the zygomatic arch in the superficial layer of temporal fascia and dissection proceeds within the superficial temporal fat pad. The supratemporal access exposes the zygomatic arch because of the dissection below the temporal fascia. During dissection, the facial nerve is protected by the entire superficial temporal fat pad, temporal fascia, and temporoparietal fascia. With the traditional access, the division and separation of the superficial temporal fat pad occur when the superficial layer of temporal fascia is incised. Occasionally, the temporal branch of the facial nerve is located very close to this anatomic point, which increases the risk of nerve injury. The authors found a lesser rate of facial nerve injury with the supratemporal access [

11].

It should be pointed out that two techniques were used to gain access to the foreign body in the present case:

Skin incision (temporal access), which allowed the rapid, practical access to the infratemporal fossa.

Subcutaneous incision (supratemporal access described by Luo et al) to minimize the risk of injury to the facial nerve.

The temporal approach was employed because the extremity of the object was palpable and lodged in the infratemporal fossa. In comparison to coronal access, the temporal approach combined with the supratemporal approach offers the advantages of fast execution, a lesser risk of nerve damage, and a less visible scar (

Table 1). This article demonstrates that the temporal approach is a viable alternative for the removal of a foreign body lodged in the infratemporal fossa that provides practicality and a favorable esthetic outcome.